Abstract

Context: The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of continuous sc replacement of amylin and insulin for a 24-h period on glucose homeostasis in adolescents with type 1diabetes.

Methods: Thirteen adolescents with type 1 diabetes on insulin pump therapy participated in a randomized, controlled, crossover design study comparing continuous sc insulin monotherapy (part A) vs. continuous sc insulin and pramlintide infusion (part B). In part A, basal and bolus insulin infusion was per prescribed home regimen. In part B, the basal insulin infusion was the same as part A, but prandial insulin boluses were reduced by 20%. Basal and prandial bolus pramlintide were administered simultaneously via another pump. All boluses were given as a dual wave.

Results: The study regimen resulted in a 26% reduction in postprandial hyperglycemia as compared to insulin monotherapy (area under the curve, 600 min, 2610 ± 539 vs. 692 ± 861 mg/liter · min) (P < 0.008). Glucagon concentrations were suppressed postprandially (P < 0.003) but not in the postabsorptive state, whereas plasma insulin concentrations were unchanged.

Conclusions: Simultaneous continuous sc pramlintide and insulin infusion has the potential of improving glucose concentrations by way of physiological replacement.

Amylin and insulin deficiency in type 1 diabetes can be overcome by the physiologic replacement of these hormones via a simultaneous, subcutaneous basal-bolus regimen.

Improving glycemic control results in delaying and/or preventing long-term complications associated with type 1 diabetes. Insulin replacement and carbohydrate counting is the mainstay of management. The recent introduction of pramlintide, the synthetic analog of the hormone amylin, in the management of diabetes allows us to improve overall glucose homeostasis by dampening postmeal glucose excursions.

Pancreatic β-cells secrete insulin and amylin in concert to maintain normal blood glucose concentrations. In type 1 diabetes, there is insulin and amylin deficiency. Amylin replacement slows gastric emptying (1,2) and suppresses meal-related increase in glucagon secretion (3,4). Hence, postprandial glucose concentrations are improved with adjunctive therapy with pramlintide, a synthetic analog of amylin.

Premeal replacement of pramlintide results in lowering of postprandial glucose excursions (5). However, in some patients, there may be immediate postprandial hypoglycemia followed by late postprandial hyperglycemia. To counter meal-related hypoglycemia, it is suggested that the preprandial bolus of insulin be reduced by 50% initially (pramlintide package insert). Despite these recommendations, pramlintide replacement remains imperfect. Early postprandial hypoglycemia and late postprandial hyperglycemia confound the use of prandial pramlintide replacement (6).

We hypothesized that blood glucose concentrations will be normalized by amylin replacement pre- and postprandially. In this trial, sc continuous insulin and pramlintide replacement was compared with insulin monotherapy in adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

Subjects and Methods

The Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine approved this investigator-initiated study. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines before entry into this trial.

Subjects

Type 1 diabetes patients on sc insulin pump therapy, aged 13–22 yr, and with disease duration of at least 1 yr were recruited. Subjects had normal body mass index (BMI) (<90th percentile for age), hemoglobin greater than 12 g/dl, and hemoglobin A1C below 8.5%. They had no other chronic conditions except treated hypothyroidism. All subjects were on insulin Lispro (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN), except two who were on insulin Aspart (Novo Nordisk, Inc., Princeton, NJ). They were not on any other medications that could affect glucose concentrations. Subjects had a normal physical exam and were Tanner staged. Pregnant and lactating females were excluded from the study. A total of 14 subjects were screened. One subject screened out because of high BMI. The first two subjects participated in the study, which was amended based on the results obtained. One subject chose to drop out after one study, and another subject’s data could not be analyzed due to missing hormone samples. Data on nine subjects with diabetes are presented.

Initial design

Basal and bolus insulin doses were reduced by 30% when pramlintide was given simultaneously. After two subjects completed their studies, it was apparent that they became markedly hyperglycemic on d 2. We inferred that the insulin dose reduction was too large. The protocol was amended such that basal insulin dose was no longer reduced throughout the study, and bolus insulin dose was reduced by only 20%, when pramlintide was bolused simultaneously.

Amended design

Subjects underwent two studies, part A and part B, in random order at least 4 wk apart. The same subjects participated in both parts A and B.

Part A

Subjects received insulin as per their usual home regimen without a reduction in basal or bolus doses.

Day 1.

The subjects were admitted to the General Clinical Research Center at 1400 h. Insulin infusion through the sc pump was continued as per home regimen. At 1630 h, an indwelling iv line was inserted to draw blood and to administer glucose in the event of hypoglycemia (corrected with 5 to 7 g of 50% dextrose in water solution when blood glucose level was below 55 mg/dl). Dinner was served at 1800 h, and a bedtime snack was offered at 2100 h. The subject received a bolus of insulin that was administered by dual wave bolus, with 70% of the dose given instantly and the remaining 30% given over the next hour with dinner and the bedtime snack. The meal and snack were based on their usual carbohydrate-consistent diet. The insulin doses before dinner and before snack were calculated as per home regimen, based on the insulin to carbohydrate ratio and sensitivity factor (the drop in blood glucose concentration, measured in milligrams per deciliter, caused by each unit of insulin taken).

Day 2.

At 0700 h, the prebreakfast insulin bolus was administered as a dual wave through the insulin pump. The insulin dose was based on the patient’s usual insulin to carbohydrate ratio. After the insulin bolus, the subject was offered 12 ounces of a standard liquid meal of Boost High Protein Drink, which was consumed within 10 min. The subject received lunch at 1200 h and dinner at 1700 h. The study ended at 1700 h.

Blood samples for the assay of glucose, insulin, glucagon, and pramlintide (in part B only) were collected at regularly timed intervals throughout the study.

Part B

This part was identical in every respect to part A, except that prandial insulin was reduced by 20% on d 2 for breakfast and lunch. Pramlintide was given as basal and premeal boluses along with insulin. The subjects maintained their usual insulin basal rates. The differences are outlined below.

Day 1.

At 1700 h, a separate infusion site for pramlintide was inserted, and the basal infusion was started.

Day 2.

At 0700 and 1200 h, pramlintide was administered as a dual wave bolus with meals. Pramlintide infusion was stopped at 1700 h, and the study ended. The subject was given a meal and discharged home with a designated adult driver due to the possibility of hypoglycemia related to pramlintide.

Pramlintide acetate dosing

Pramlintide acetate dosing was based on each subject’s usual insulin requirements (insulin/kg · d). Basal dose was calculated at 3–5 μg/h. If subjects were using less than 0.8, 1, or more than 1 U/kg · d of insulin, they received 3, 4, or 5 μg/h of basal pramlintide, respectively. Pramlintide bolus was based on insulin to pramlintide ratio. For every unit of insulin, 5 μg of pramlintide was given. Insulin and pramlintide bolus doses were delivered as dual wave boluses with 70% of dose given immediately and 30% over 1 h. Pramlintide was delivered using a Medtronic Paradigm 512 infusion pump.

Meals

The meal amounts were matched between parts A and B for the same subject.

Day 1:

dinner, 60–80 g carbohydrate (macronutrient composition was 50% carbohydrates, 30% protein, and 20% fat); bedtime snack, 30 g carbohydrate with a similar macronutrient composition as at dinner.

Day 2:

breakfast, 12 ounces of Boost High Protein Drink (360 cal; 50 g carbohydrate, 9 g fat, and 22 g protein); lunch, 60–80 g carbohydrate (the macronutrient composition was 50% carbohydrates, 30% protein, and 20% fat).

Measurements

Blood glucose was measured at the bedside using a YSI glucose analyzer (2300 Stat Plus; Yellow Springs Instruments Company Inc., Yellow Springs, OH) throughout the study at regularly timed intervals. Blood samples were collected pre- and postprandially for pramlintide (part B only), and for insulin and glucagon in both parts. After collection, blood was processed in a refrigerated centrifuge at 4 C for 10 min at 3000 rpm. Plasma was collected in labeled microfuge tubes and stored in an ultra-low freezer at −70 C.

The DCA 2000 Hemoglobin A1C System (Bayer, Elkhart, IN) was used for measuring the percentage concentration of hemoglobin A1C in blood.

An ultra-sensitive RIA determines ultrafiltrate insulin with a detection limit of 0.5 μU/ml. Glucagon was measured using an immunoassay specific to pancreatic glucagon with 4.5% intraassay variability and a 7.1% interassay variability. All hormone assays were done at Millipore Inc (Billerica, MA).

Statistics

Comparative and descriptive statistics, figures, and graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism version 4.03 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). ANOVA for repeated measures was used to analyze the glucose, and hormonal data with post hoc analysis using a paired two-tailed Student t tests was applied.

A total mean area under the curve was calculated from basal values before breakfast to the end of the study. For analysis, the trapezoidal rule Excel version 7.0 was applied and was compared using two-way ANOVA. Data were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Subjects had moderately controlled type 1 diabetes with hemoglobin A1C of 7.4 ± 0.7%. Baseline characteristics of cohort are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics in subjects

| Characteristic | Mean ± sd (range) |

|---|---|

| Gender | 6 Males/3 females |

| Age (yr) | 17 ± 2 (14–21) |

| Pulse (beats/min) | 77 ± 8 (64–89) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 121 ± 8 (103–128) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 68 ± 7 (58–82) |

| Height (m) | 1.7 ± 0.09 (1.62–1.9) |

| Weight (kg) | 69 ± 8 (53.3–88.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22 ± 3 (17–26.8) |

| Hemoglobin A1C (%) | 7.4 ± 0.7 (6.6–8.5) |

| Total insulin (U/kg · d) | 0.8 ± 0.2 (0.15–9.4) |

| Insulin basal (%) | 42 ± 14.7 (16–64) |

Glucose and hormonal measurements

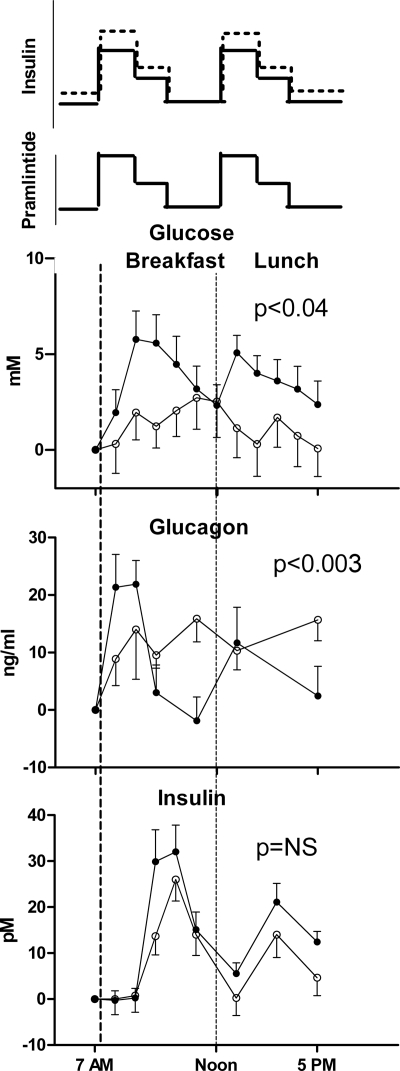

Subjects had euglycemia with pramlintide infusion. Only one participant needed extra glucose iv as per protocol when concurrent pramlintide and insulin were infused. Postprandial hyperglycemia was reduced with dual wave pramlintide and insulin infusion compared with dual wave insulin monotherapy (Fig. 1). This correlated with a reduction in area under the curve for glucose during the morning postprandial period (2610 ± 539 vs. 692 ± 861 mg/liter · min; P < 0.008).

Figure 1.

Top panel, Schematic representation of insulin and pramlintide delivery as a 70–30 dual wave bolus. Part A insulin is shown as a dotted line, and part B pramlintide and insulin are shown as solid lines. Blood glucose change from baseline is shown from 0700 to 1700 h. The graphs include two meals: breakfast is a liquid meal, and lunch is a solid meal. Middle panel displays corresponding glucagon concentrations, and lower panel shows insulin concentrations between the two studies. Closed circles represent part A, (insulin only) and open circles represent part B, (insulin and Pramlintide). Data are expressed as mean and sem.

Glucagon concentrations were statistically (P < 0.003) suppressed in the postprandial period during the day when pramlintide was used. There were no statistical differences in glucose, insulin, and glucagon concentrations during the night when pramlintide was administered in conjunction with insulin (P = not significant).

Despite decreasing prandial insulin boluses by 20%, insulin concentrations were not statistically different between the two groups during either the day or night.

Adverse events

Four subjects required iv dextrose for low blood glucose of less than 3 mm during the night when pramlintide was delivered of the amended protocol. The nadir of blood glucose reached was 2.8, 2.3, 2.4, and 3 mm, respectively. Subjects did not have symptoms associated with hypoglycemia. Two of the four subjects that had hypoglycemia with pramlintide also had hypoglycemia postmeal in part A, when pramlintide was not delivered. One subject had a blood glucose of 3.0 mm during the postmeal period. The subject also experienced nausea. Both of these events were treated as per protocol with dextrose and Zofran, respectively. Hypoglycemia and nausea resolved, and the study was continued and completed. Another subject in part A also had hypoglycemia after lunch (3 mm) that resolved with treatment.

One subject complained of headache (part A), and it was attributed to severe teeth grinding during the night. One subject received an inadvertently higher dose of pramlintide for breakfast. However, this did not result in hypoglycemia, and the patient did well.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated for the first time proof of principle and feasibility data on sc delivery of pramlintide for a 24-h period. Postprandial glycemic excursions were improved without an increase in hypoglycemia during the day. A 20% decrease in premeal insulin boluses was sufficient to prevent immediate postprandial hypoglycemia. We previously demonstrated that immediate postprandial hypoglycemia was a significant limiting factor in using pramlintide in type 1 diabetes (7). To combat this immediate postprandial hypoglycemia, we attempted to deliver pramlintide as a square wave bolus (6). Although, this attenuated immediate postprandial hypoglycemia, there was no improvement in overall postprandial hyperglycemic excursions. In this trial, we have used a dual wave bolus to deliver insulin and pramlintide. Dual wave bolus allows the delivery of pramlintide in an efficient and semiphysiological manner in the immediate postprandial period. A recent study in pediatric patients suggested that dual wave bolus of insulin was superior in reducing postprandial glycemic excursions compared with a standard regular bolus (8).

This is the first study using simultaneous pramlintide and insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes. Hence, at the outset, it was not known whether the basal rates of insulin would need reduction. With just two subjects, we noted postprandial hyperglycemia on the second day of the study. This prompted a revision of the protocol, and basal rates were continued without reduction. It remains to be determined whether the rates we chose would differ if patients had an active lifestyle. It is also unknown whether pramlintide in the setting of intensive insulin management further exacerbates hypoglycemia unawareness because the subjects were asymptomatic with biochemical hypoglycemia. Counter-regulation is noted to be lower during the night, even with just insulin therapy (9). The limitation of this study is that pramlintide/insulin dose during the night may be high, and in light of nocturnal hypoglycemia we suggest that further lowering of insulin/pramlintide during the night may be needed for future protocols. Continuous glucose monitoring may help in optimizing therapy and improving postprandial glycemic excursions.

Glucagon concentrations were suppressed after pramlintide injections were used in the postmeal period in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes (10,11). We found that our study is in concordance with the previous reports on the mechanism of action of pramlintide. Pramlintide dual wave infusion demonstrates this lowering of glucagon as seen with injection. However, we had noted an absence of glucagon suppression with pramlintide square wave bolus infusion (6). Interestingly, in the late postprandial period we noted an increase in glucagon. This may actually be beneficial for patients in avoiding late postprandial hypoglycemia.

These data are proof of the principle that pramlintide can be delivered simultaneously in a continuous, sc regimen with insulin. This resulted in improved overall glycemic excursions in young adults with type 1 diabetes. Further studies using continuous, sc insulin and pramlintide for a longer period of time are necessary to see if this has beneficial effects on long-term glycemic control.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants DK065059 and R01DK077166-01 (to R.A.H.). R.A.H. is a McNair scholar and is supported by The Robert and Janice McNair Foundation, McNair Scholars Program at Texas Children’s Hospital. L.M.R. is supported by NIH Grant K23 DK075931, and M.W.H. is supported by NIH Grant RO1 DK055478 and Children’s Nutrition Research Center (current research information system) Grant 2533710353.

This work is a publication of the U.S. Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of policies of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement from the U.S. Government.

This study is registered with clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00291772.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online February 3, 2009

Abbreviation: BMI, Body mass index.

References

- Moyses C, Young A, Kolterman O 1996 Modulation of gastric emptying as a therapeutic approach to glycaemic control. Diabet Med 13:S34–S38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsom M, Szarka LA, Camilleri M, Vella A, Zinsmeister AR, Rizza RA 2000 Pramlintide, an amylin analog, selectively delays gastric emptying: potential role of vagal inhibition. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 278:G946–G951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gedulin BR, Rink TJ, Young AA 1997 Dose-response for glucagonostatic effect of amylin in rats. Metabolism 46:67–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orskov L, Nyholm B, Yde Hove K, Gravholt CH, Moller N, Schmitz O 1999 Effects of the amylin analogue pramlintide on hepatic glucagon responses and intermediary metabolism in type 1 diabetic subjects. Diabet Med 16:867–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyer C, Gottlieb A, Kim DD, Lutz K, Schwartz S, Gutierrez M, Wang Y, Ruggles JA, Kolterman OG, Maggs DG 2003 Pramlintide reduces postprandial glucose excursions when added to regular insulin or insulin lispro in subjects with type 1 diabetes: a dose-timing study. Diabetes Care 26:3074–3079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, Mason KJ, Haymond MW, Heptulla RA 2007 The role of prandial pramlintide in the treatment of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Res 62:746–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heptulla RA, Rodriguez LM, Bomgaars L, Haymond MW 2005 The role of amylin and glucagon in the dampening of glycemic excursions in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 54:1100–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell MA, Gilbertson HR, Donath SM, Cameron FJ 2008 Optimizing postprandial glycemia in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes using insulin pump therapy: impact of glycemic index and prandial bolus type. Diabetes Care 31:1491–1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TW, Porter P, Sherwin RS, Davis EA, O'Leary P, Frazer F, Byrne G, Stick S, Tamborlane WV 1998 Decreased epinephrine responses to hypoglycemia during sleep. N Engl J Med 338:1657–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholm B, Orskov L, Hove KY, Gravholt CH, Moller N, Alberti KG, Moyses C, Kolterman O, Schmitz O 1999 The amylin analog pramlintide improves glycemic control and reduces postprandial glucagon concentrations in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 48:935–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolterman OG, Schwartz S, Corder C, Levy B, Klaff L, Peterson J, Gottlieb A 1996 Effect of 14 days’ subcutaneous administration of the human amylin analogue, pramlintide (AC137), on an intravenous insulin challenge and response to a standard liquid meal in patients with IDDM. Diabetologia 39:492–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]