Abstract

One-carbon metabolism plays a critical role in both DNA methylation and DNA synthesis. Accumulating evidence has shown that interruptions of this pathway are associated with many disease outcomes including cardiovascular diseases and cancers. Mechanistic studies have been performed on genetic polymorphisms involved in one-carbon metabolism. However, expression profiles of these inter-related genes are not well-known. In this study, we examined the gene expression profiles of 11 one-carbon metabolizing genes by quantifying the mRNA level of the lymphocyte among 54 healthy individuals and explored the correlations of these genes. We found these genes were expressed in lymphocytes at moderate levels and showed significant inter-person variations. We also applied principle component analysis to explore potential patterns of expression. The components identified by the program agreed with existing knowledge about one-carbon metabolism. This study helps us better understand the biological functions of one-carbon metabolism.

Keywords: one-carbon metabolism, expression, principle component analysis (PCA)

Introduction

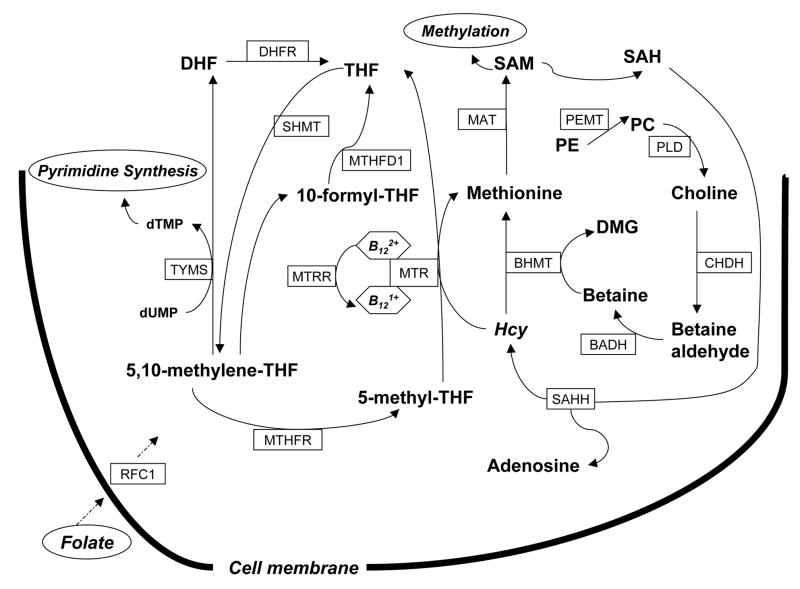

One-carbon metabolism (Figure 1) is a network of interrelated biological reactions in One-carbon metabolism (Fig. 1) is a network of interrelated biological reactions in which a one-carbon moiety from a donor compound is transferred to tetrahydrofolate (THF) for subsequent reduction or oxidation (Machlin, 1991). One-carbon metabolism plays a critical role in both DNA methylation and DNA synthesis, and in turn impacts both genetic and epigenetic processes in disease etiology (Stern et al., 2000; Xu, et al., 2009). A low methyl supply can induce DNA global hypomethylation as well as deficient conversion of deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) to deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP) leading to uracil misincorporation into DNA (Blount et al., 1997). Because of the essential roles in these critical processes, one-carbon metabolism is capable of influencing many biological functions.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of one-carbon metabolism, choline and methionine pathway. Key genes include: dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), methionine synthase (MTR), methionine synthase reducatase (MTRR), serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT), thymidylate synthase (TYMS), phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT), choline dehydrogenase (CHDH), betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT), reduced folate carrier 1 (RFC1), and methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 (MTHFD1). Hcy, homocysteine; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SAH, S-adenosylhomocystein; THF, tetrahydrofolate; DHF, dihydrofolate; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; DMG, N,N-dimethylglycine; PLD, phospholipase D; BADH, betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase; SAHH, S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase; MAT, methionine adenosyltransferase; dTMP, deoxythymidine monophosphate; dUMP, deoxyuridine monophosphate..

Evidence from animal and human studies as well as epidemiological observations supports the important role of one-carbon metabolism in pathogenesis and progression of diseases (Beaudin et al., 2007;Celtikci et al., 2007; Bagnyukova et al., 2008). On one hand, one-carbon related nutrient (i.e., folate, methionine, choline and vitamins B) statuses have been found to be associated with several disease outcomes (Slopien et al., 2008; Suzuki et al., 2008). Genetic polymorphisms, on the other hand, could have functional impacts on the pathway and affect metabolism balance. One example is the MTHFR 677C>T (rs1801133) polymorphism. The TT variant homozygotes have 70% lower enzyme activitycompared with CC wild-type homozygotes, whereas CT heterozygotes retain 65% enzyme activity (Frosst et al., 1995). Furthermore, this polymorphism has been independently associated with serum folate and homocysteine(Hcy) concentrations (Bailey et al., 1999; Ulvik et al., 2007).

Despite accumulating epidemiologic studies on one-carbon metabolism and disease outcomes, little data exist on systematic examination of the expression profiles of the one-carbon metabolizing genes in population studies. There are modeling-based studies (Reed et al., 2006; Ulrich et al., 2006) to understand biological mechanisms linking this pathway to disease outcomes and to predict gene-gene and gene-diet interactions. However, how these modeling results may be translated into general population is unknown. Aiming to better understand one-carbon metabolism in human body, we investigated the gene expression profiles of the one-carbon metabolizing genes by quantifying the mRNA levels among a group of healthy individuals and explored the correlation among the expression levels of these genes.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Blood samples from 54 anonymous healthy donors were collected from the New York Blood Center, USA. The research protocols have been reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board of Mount Sinai School of Medicine, USA. Lymphocytes were isolated from buffy coats by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Histopaque, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at 2,300 r/min and homogenized using QIAshredder Mini Spin Column (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA).

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from lymphocytes with Qiagen RNAeasy mini kit (QIAGEN). The concentrations of RNA were measured using Nanodrop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and stored at −70°C. Up to 4.5 μg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using random primers according to Stratagene AffinityScript™ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was purified with Qiagen purification kit (QIAGEN) and eluted with 30μL TE. Scitools (Integrated DNA technologies, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to design the gene specific primers expanding 130–200 base pairs. Forward and reverse primers of each gene were designed to span different exons to eliminate genomic DNA contamination.

Quantification of expression level

Gene-specific primers were used for quantification of the one-carbon metabolizing gene expressions (Table 1). The 15μL reaction mix contained the following components with final concentration: 1 × AmpliTaq buffer, 20% glycerol, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 0.2 mmol/L dNTP (dUTP replacing dTTP), 4.0 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.5μmol/L primers, 0.2 × SYBR Green (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA), 2 U AmpliTaq Gold (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA), and 2 μL of 1:10 dilution of single stranded cDNA. The real time PCR was performed on Roche LightCycler® 480 with cycling condition of 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 62°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. All reactions were run on duplicate for 54 samples. Melting curves were checked to validate the PCR specificity. Expression of β-actin was measured for each sample for normalization of input template. Serial dilutions were used to generate the standard curve to check the linear amplifications and to calculate copy number of each gene relative to β-actin (Bustin, 2000; Livak et al., 2001).

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for expression quatification of one-carbon metabolizing genes

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) | GAATCACCCAGGCCATCTTA | GCCTTTCTCCTCCTGGACAT |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT) | TCAAGGAGGCGAGAGTGA | CCAGGTAGTTGGCTGTGCTT |

| Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 (MTHFD1) | GATGAAGTACATTACATCTTTGAATGAA | CATCCTTCTCGGGTGCAA |

| Methionine synthase (MTR) | GAACATATCTGTGGCTGAGGTTGA | TTTCCTTGAGGATCATCAAGAATAA |

| Methionine synthase reductase (MTRR) | CTACCTTCAGGATATTTGGTCATAA | TCCACTCCATGTCCTTCAAGAA |

| Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT) | ACAAGTGGCTGATGAAGGAGAT | CGTTCTTCTTCATAAAGACCTCTAA |

| Methylenetetranydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) | CTGCTGCACCAGAGTGAAAG | TATGGCCCTTGGACCTACTG |

| Serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) | CAATGACGATGCCAGTCAA | GAGGGGTTGTGCCAGCA |

| Thymidylate synthase (TYMS) | GAGAACCCAGACCTTTCCCAA | TTTGAAAGCACCCTAAACAGCC |

| Reduced folate carrier 1 (RFC1) | AATGAAGAAAACACTAAGACCAAGAA | CTTGCCACCATCTTCTTATTAGA |

| Choline dehydrogenase (CHDH) | TCTGAGTGGAGGTGCCATCAA | ATGCCCAGTTTCAAGAGGTCA |

| β-actin | ACTGGAACGGTGAAGGTGAC | GTGGACTTGGGAGAGGACTG |

Statistical analyses

The mean Ct values of the duplicate measurements were used for analysis. We standardized the gene expression data against β-actin. Descriptive analyses were performed to examine the distribution of the expression level. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated for all gene pairs. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed and the number of components to evaluate was based on evaluating the proportion of variability explained, though this determination was not based on any formal rule. For each component, the loadings of each variable (gene) on that component are examined to suggest what that component represents. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.1(SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results and Discussion

We examined the expression levels of 11 one-carbon metabolizing genes (Table 2) in lymphocytes of 54 healthy blood donors. Expression levels of these genes ranged from ~3 copies per cell for SHMT to ~120 copies per cell for MTR. The expression levels relative to β-actin among the genes range from 0.3% for BHMT to 7.5% for DHFR. The expression levels of the genes vary among individuals with the standard deviation ranging from 0.7 to 16.

Table 2.

One-carbon metabolism gene expression data

| Gene | Copy number1 (mean) | % Relative to β-actin | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHFR | 71.1 | 7.5 | 9.2 | 3.2 | 0.7 | 53.6 |

| PEMT | 11.5 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 20.1 |

| MTHFD | 12.0 | 1.4 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 21.8 |

| MTR | 120.9 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 12.5 |

| MTRR | 21.1 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 22.9 |

| BHMT | 4.7 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 4.9 |

| MTHFR | 13.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 4.2 |

| SHMT | 2.9 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 11.0 |

| TYMS | 12.7 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 6.5 |

| RFC1 | 64.2 | 7.1 | 16.0 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 113.1 |

| CHDH | 4.3 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 4.3 |

Copy number derived using standard curve method.

Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated in a pairwise manner. We observed significant correlations between most gene-pairs with the exception of MTR, BHMT and CHDH, which are weakly correlated with other genes. The 8 genes DHFR,PEMT, MTHFD, MTRR, SHMT, TYMS, RFC1 and MTHFR were tightly correlated with each other (P<0.001), with correlations ranging from 0.58 to 0.92, with a median correlation of 0.79. The correlations of these 8 genes with the remaining 3 genes (MTR, BHMT, CHDH) was lower ranging from −0.06 to 0.60 with a median correlation of 0.35. This pattern of correlation indicates two gene groups. While MTR, BHMT and CHDH are involved in the methionine metabolizing cycle, the rest, except for PEMT, are involved in the folate metabolizing cycle.

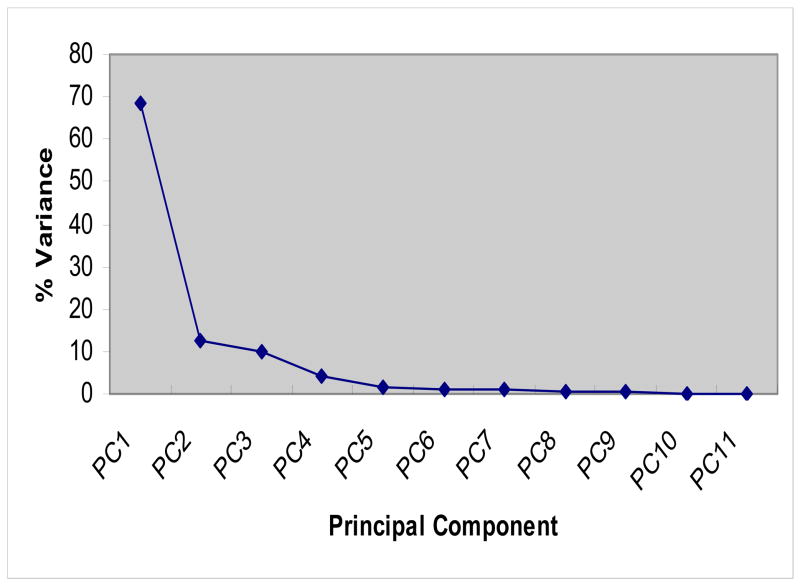

PCA is a multivariate technique for examining relationships among several quantitative variables (Ringner, 2008). PCA reduces the complexity of the data and enables large data to be analyzed simultaneously while retaining the essential information. It has been applied to analyze microarray data (Song et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2008). We applied PCA for the expression data of 11 one-carbon metabolizing genes aiming to detect any inter-relationship and potential regulatory mechanisms of this pathway. Since in practice this analysis requires at least an approximately normal distribution, with minimal skewness, we transformed the data using Y = ln(1+X), X = original data, Y = transformed data, prior to analysis. From the eigenvalues of the PCA, it was calculated that the first three principle components (PCs) explained 68.5%, 12.7% and 10.2% of the total variance, respectively, totaling 91.4% of the total variance of gene expressions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The variances explained by each of principal components identified by PCA

Among these three PCs, the first PC explained the most observed variance, 68.5%. All 11 genes had positive, mostly nearly equal, loadings for this first component (Table 3). This implied that all genes were equally important with house-keeping properties, consistent with function of the one-carbon metabolism in DNA synthesis with the exception of MTR with a loading of 0.107; the rest had loadings close to 0.3. MTR catalyzes the conversion of homocysteine to methione, during which the cofactor cob(I)alamin is oxidized to cob(II)alamin resulting in inactivation of the enzyme (Shane, 1989; Appling, 1991). Such mechanism may be different from other regulatory mechanisms such as regulating gene expression by itself.

Table 3.

Loading values of the first three principal components for each gene

| Gene | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DHFR | 0.336 | −0.135 | −0.205 |

| PEMT | 0.347 | −0.108 | 0.160 |

| MTHFD | 0.347 | −0.180 | 0.124 |

| MTR | 0.107 | 0.612 | 0.470 |

| MTRR | 0.345 | −0.131 | 0.140 |

| BHMT | 0.296 | 0.335 | 0.224 |

| MTHFR | 0.251 | 0.005 | −0.590 |

| SHMT | 0.337 | −0.144 | 0.059 |

| TYMS | 0.330 | 0.268 | −0.095 |

| RFC1 | 0.295 | −0.371 | 0.247 |

| CHDH | 0.238 | 0.441 | −0.452 |

PC: Principal component.

The second component of PC consisted of MTR, CHDH, BHMT and TYMS genes, which had high positive loadings, and RFC1, which had a negative loading. This group of genes is involved in the maintenance of the methyl pool. By looking at the enzyme functions, CHDH catalyzes the oxidation of choline to betaine via a betaine-aldehyde intermediate. Both MTR and BHMT catalyze the remethylation of homocysteine using different methyl donors, i.e., 5-methyl-THF and betaine, respectively. The product methionine is then be adenylated to form S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), which serves as the universal methyl donor for numerous cellular methylation reactions (Shane, 1989; Appling, 1991). On the other hand, TYMS uses cofactor 5,10-methylene-THF in the methylation of deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) to form thymidine monophosphate (dTMP), which then goes into the DNA synthesis process. RFC1, a membrane transporter, is responsible to transport folate (i.e., 5-methyl-THF) into the cell.

For the third component, MTR showed high positive loading, whereas MTHFR and CHDH showed high negative loadings. What this component represents for is not clear. We noticed that MTHFR and MTR are related to regulation of cellular homocysteine levels. It is known that AdoHcy is a potent inhibitor of certain AdoMet-dependent methylation reactions (Hoffman et al., 1980). In addition, accumulation of AdoMet inhibits the enzyme MTHFR (Jencks et al., 1987), preventing the accumulation of 5-methyl-THF when cellular levels of methionine are sufficient to meet methylation demands. Because the reduction of 5,10-methylene-THF to 5-methyl-THF catalyzed by MTHFR is irreversible, disruptions in the methionine cycle result in accumulation of 5-methyl-THF at the expense of all other folate derivatives.

Taking together, the results of PCA showed: 1) all one-carbon metabolizing genes are important in maintaining normal cellular functions. Several levels of regulatory mechanisms are involved. This is consistent with existing knowledge. 2) Folate plays critical role in the one-carbon metabolism pathway. The efficiency of folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism also depends on the total THF cofactors pool. Abundant evidence from both experimental and observation studies shows that folate deficiency could disrupt the normal DNA synthesis and methylation causing cellular abnormalities. 3) Reactions in this pathway are tightly regulated by the cellular environments by different feedback loops.

We have very limited information about the blood donors in our study. Certain factors, such as dietary intake, which may influence the gene expression, are not available. We acknowledge these limitations of the study. Nevertheless, results from this study will serve as background information of one-carbon metabolism for future epidemiologic studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA109753) and Department of Defense (BC031746 and training award W81XWH-06-1-0298).

Abbreviations

- MTHFR

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase

- MTR

Methionine synthase

- RFC1

Reduced folate carrier 1

- BHMT

Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase

- CHDH

Choline dehydrogenase

- PCA

Principal component analysis

References

- Appling D. Compartmentation of folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism in eukaryotes. FASEB J. 1991;5:2645–2651. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.12.1916088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnyukova TV, Powell CL, Pavliv O, Tryndyak VP, Pogribny IP. Induction of oxidative stress and DNA damage in rat brain by a folate/methyl-deficient diet. Brain Res. 2008;1237:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey LB, Gregory JF., 3rd Polymorphisms of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and other enzymes: metabolic significance, risks and impact on folate requirement. J Nutr. 1999;129:919–922. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.5.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudin AE, Stover PJ. Folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism and neural tube defects: Balancing genome synthesis and gene expression. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2007;81:183–203. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount BC, Mack MM, Wehr CM, MacGregor JT, Hiatt RA, Wang G, Wickramasinghe SN, Everson RB, Ames BN. Folate deficiency causes uracil misincorporation into human DNA and chromosome breakage: Implications for cancer and neuronal damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3290–3295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA. Absolute quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J Mol Endocrinol. 2000;25(2):169–93. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0250169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celtikci B, Leclerc D, Lawrance AK, Deng L, Friedman HC, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA, Melnyk S, James SJ, Peterson AC, Rozen R. Altered expression of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase modifies response to methotrexate in mice. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008;18:577–589. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32830058aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wang L, Smith JD, Zhang B. Supervised principal component analysis for gene set enrichment of microarray data with continuous or survival outcomes. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2474–2481. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosst P, Blom HJ, Milos R, Goyette P, Sheppard CA, Matthews RG, Boers GJ, den Heijer M, Kluijtmans LA, van den Heuvel LP. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Nat Genet. 1995;10:111–113. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman D, Marion D, Cornatzer W, Duerre J. S-Adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocystein metabolism in isolated rat liver. Effects of L-methionine, L-homocystein, and adenosine. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:10822–10827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks D, Mathews R. Allosteric inhibition of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase by adenosylmethionine. Effects of adenosylmethionine and NADPH on the equilibrium between active and inactive forms of the enzyme and on the kinetics of approach to equilibrium. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2485–2493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machlin LJ. Handbook of vitamins. 2. New York: M. Dekker; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Reed MC, Nijhout HF, Neuhouser ML, Gregory JF, III, Shane B, James SJ, Boynton A, Ulrich CM. A Mathematical Model Gives Insights into Nutritional and Genetic Aspects of Folate-Mediated One-Carbon Metabolism. J Nutr. 2006;136:2653–2661. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringner M. What is principal component analysis? Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:303–304. doi: 10.1038/nbt0308-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shane B. Folylpolyglutamate synthesis and role in the regulation of one-carbon metabolism. Vitam Horm. 1989;45:263–335. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopien R, Jasniewicz K, Meczekalski B, Warenik-Szymankiewicz A, Lianeri M, Jagodziski PP. Polymorphic variants of genes encoding MTHFR, MTR, and MTHFD1 and the risk of depression in postmenopausal women in poland. Maturitas. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JH, Kim HJ, Lee CH, Kim SJ, Hwang SY, Kim TS. Identification of gene expression signatures for molecular classification in human leukemia cells. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern LL, Mason JB, Selhub J, Choi SW. Genomic DNA hypomethylation, a characteristic of most cancers, is present in peripheral leukocytes of individuals who are homozygous for the C677T polymorphism in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:849–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Matsuo K, Sawaki A, Mizuno N, Hiraki A, Kawase T, Watanabe M, Nakamura T, Yamao K, Tajima K, Tanaka H. Alcohol drinking and one-carbon metabolism-related gene polymorphisms on pancreatic cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2742–2747. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich CM, Nijhout HF, Reed MC. Mathematical Modeling: Epidemiology Meets Systems Biology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:827–829. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulvik A, Ueland PM, Fredriksen A, Meyer K, Vollset SE, Hoff G, Schneede J. Functional inference of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase 677C > T and 1298A > C polymorphisms from a large-scale epidemiological study. Hum Genet. 2007;121:57–64. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Chen J. One-carbon metabolism and breast cancer: an epidemiological perspective. J Genet Genomics. 2009;36(2009):1–12. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60108-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]