Abstract

For the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR), published evidence suggests that an intact actin cytoskeleton is required for the endocytosis of receptors and their proper sorting to the rapid recycling pathway. We have characterized the role of the actin cytoskeleton in the regulation of β2AR trafficking in HEK293 cells using two distinct actin filament disrupting compounds, cytochalasin D and latrunculin B. In cells pretreated with either drug, β2AR internalization into transferrin-positive vesicles was not altered, but both agents significantly decreased the rate at which β2ARs recycled to the cell surface. In latrunculin B-treated cells, nonrecycled β2ARs were localized to EEA1-positive endosomes and also accumulated in the recycling endosome, but only a small fraction of receptors localized to LAMP-positive late endosomes and lysosomes. Treatment with latrunculin B also markedly enhanced the inhibitory effect of rab11 overexpression on receptor recycling. Dissociating receptors from actin by expression of the myosin Vb tail fragment resulted in missorting of β2ARs to the recycling endosome, while the expression of various CART fragments or the depletion of actinin-4 had no detectable effect on β2AR sorting. These results indicate that the actin cytoskeleton is required for the efficient recycling of β2ARs, a process that likely is dependent on myosin Vb.

Keywords: β2-adrenergic receptor, myosin Vb, actin cytoskeleton, rab11, recycling

Introduction

The signaling capacity of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) is dependent upon the complement of cell surface receptors coupled to their transductional G proteins. Following treatment with agonist, most GPCRs undergo a rapid loss of sensitivity to further stimulation, a process termed desensitization. For the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR), a prototypical member of the GPCR superfamily, desensitization proceeds by at least three mechanisms. Following activation by agonists, receptors rapidly are phosphorylated by protein kinase A (PKA) and by one or more G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) (1–3). Agonist occupied, GRK-phosphorylated β2ARs are bound by an arrestin protein, which fully uncouples receptors from their stimulatory G protein and serves as an adaptor linking receptors to the endocytic machinery (4–7). After a short exposure to agonist (5 min), a large fraction of receptors move into endocytic vesicles by clathrin/dynamin-mediated endocytosis, after which most receptors rapidly recycle back to the cell surface (8). These steps likely are prerequisite for receptor resensitization, because interventions that disrupt receptor recycling also inhibit their resensitization (9–11). With each round of endocytosis and recycling, a small fraction of receptors are sorted to lysosomes, where they are downregulated, and to the pericentriolar recycling endosome (RE), from which they slowly recycle (12,13). How these sorting events are regulated is unclear, but published data indicate that efficient β2AR recycling is dependent on an intact actin cytoskeleton and is regulated by hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (Hrs) (11,14–16).

The actin cytoskeleton plays an important, albeit variable, role in the trafficking of membrane receptors in both yeast and mammalian cells. The cortical actin cytoskeleton has been shown to be essential for the endocytosis, but not the recycling, of transferrin receptors in A431 cells but not in K562 or COS-7 cells (17,18). Further, disruption of the actin cytoskeleton results in decreased internalization of the G protein-coupled bombesin, thromboxane A2, and endothelin receptors (19,20). The role of the actin cytoskeleton in β2AR endocytosis remains controversial with conflicting data having been reported (15,20,21).

Less is known about the requirement of the actin cytoskeleton in other trafficking steps, such as the postendocytic sorting of receptors. In polarized epithelial cells, the actin cytoskeleton is required for maintenance of the spatial localization of basolateral membrane proteins and for the proper sorting of cargo in the RE (22). For β2ARs, their sorting to the rapid recycling pathway following agonist-induced endocytosis is dependent upon their interaction with the actin cytoskeleton, and the pharmacologic depolymerization of the actin cytoskeleton also inhibits β2AR recycling (14,15). However, neither the extent of impairment of β2AR recycling nor the specific intracellular trafficking itinerary of receptors has been determined following actin depolymerization.

Recent evidence implicates Hrs, an endosome-associated protein, as a regulator of β2AR recycling (11). Hrs is a member of a protein complex that links early endosome cargo to the actin cytoskeleton (23). This complex, termed the cytoskeleton-associated recycling and transport (CART) complex, consists of Hrs/actinin-4/BERP/myosin Vb, which interact sequentially with their neighboring proteins (23). Disruption of the endosome membrane localization of Hrs or the binding of any CART protein with its neighboring protein inhibits the actin cytoskeleton-dependent recycling of transferrin receptors, causing them to be sorted to the slow recycling pathway via the recycling endosome (23). Depletion or overepression of Hrs also inhibits β2AR recycling (11).

We sought to determine if the actin cytoskeleton is required for β2AR internalization in HEK293 cells and to establish which intracellular steps are altered following disruption of the actin cytoskeleton. Further, given the apparent role of Hrs as a regulator of β2AR recycling, we also determined if the CART complex likewise regulates β2AR trafficking.

Results

Latrunculin B and cytochalasin D disrupt cortical actin in HEK293 cells

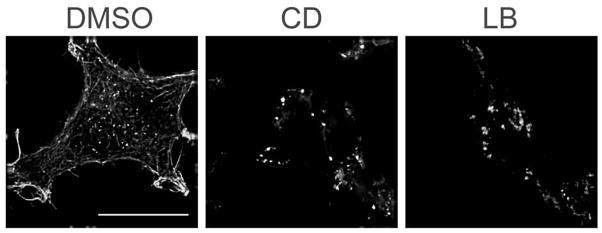

We selected concentrations of latrunculin B (LB) and cytochalasin D (CD) based on published data showing inhibitor-mediated alterations in vesicular trafficking in this (14) or other cells lines (18). To test the effects of these agents in HEK293 cells stably overexpressing human β2ARs (12β6 cell line), we treated cells growing on Matrigel-coated glass coverslips with DMSO (1:1000), LB (10 μg/ml), or CD (2 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed, labeled with phalloidin-Texas Red, and the distribution of cortical actin was determined using deconvolution fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1). In DMSO-treated cells, cortical actin filaments and stress fibers are readily apparent in views taken just beneath the plasma membrane. In contrast, in cells treated with LB or CD, F-actin is distributed in peripheral aggregates and actin filaments are lost. Treatment with either actin inhibitor induced morphologic changes in most cells, with cells becoming rounded and contracted.

Figure 1.

Pharmacologic disruption of actin cytoskeletion. 12β6 cells were treated with DMSO (1:1000), latrunculin B (LB, 10 μg/ml), or cytochalasin D (CD, 2 μM) for 30 min, then fixed and stained using phalloidin-Texas Red to identify the actin cytoskeleton. Cells were imaged by fluorescence microscopy and the resulting micrographs optimized by deconvolution. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Effect of latrunculin B and cytochalasin D on β2AR endocytosis

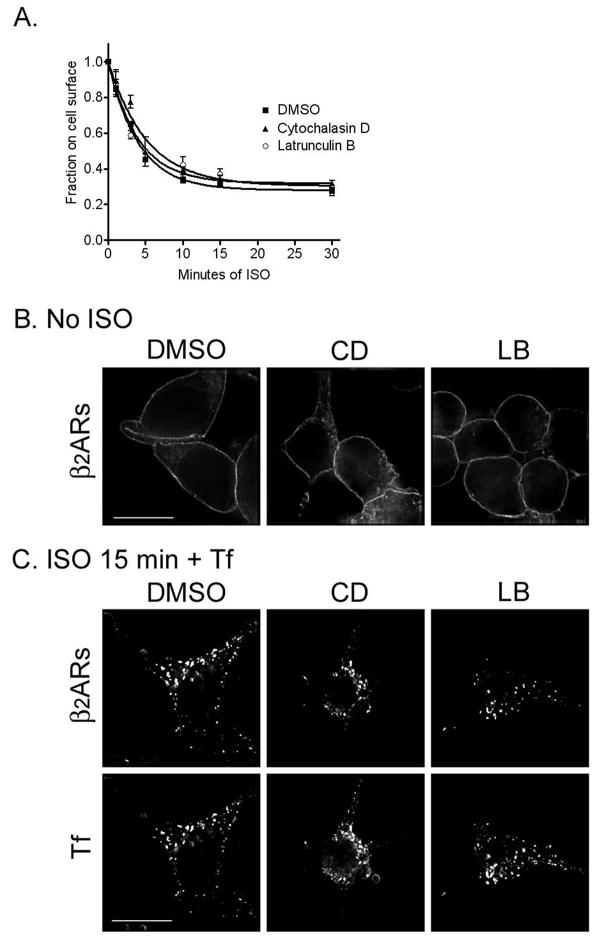

The actin cytoskeleton is known to be involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin receptors, although this requirement may be variable among cell lines. For β2ARs, there are conflicting reports as to the requirement of the actin cytoskeleton in agonist-induced receptor endocytosis, with two studies showing no requirement for actin in agonist-induced receptor internalization and one study showing that receptor internalization is dependent on an intact actin cytoskeleton (15,20,21). However, much of this data was based on the morphologic appearance of receptors or on the loss of radioligand binding sites at a single time point of agonist treatment. Thus, we sought to measure both the kinetics and extent of β2AR internalization following the chemical depolymerization of actin. We pretreated serum starved 12β6 cells growing on Matrigel-coated 24 well clusters with DMSO, LB, or CD for 30 min as described above, then added isoproterenol (ISO, 5 μM) for varying times up to 30 min to stimulate β2AR internalization. We monitored receptor internalization both by radioligand binding (Fig. 2A) and immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2B, C). Treatment with either LB or CD had no effect on the cell surface distribution of receptors at baseline (Fig. 2B) or on either the rate or extent of β2AR internalization into endosomes, where they largely localized with pulsed fluorescently-tagged transferrin (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Internalization of β2ARs following actin depolymerization. (A) 12β6 cells were treated with DMSO, LB, or CD for 30 min and then exposed to 5 μM ISO for varying times up to 30 min. After washing, surface receptor numbers were determined by measuring the binding of the hydrophilic radioligand [3H]CGP12177 The fraction of receptors left on the surface was plotted as a function of time after addition of agonist and the curves fitted as previously described (8). Each point represents the means ± s.e.m. of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate, and the rate constants are for DMSO 0.252 ± 0.021; for CD 0.212 ± 0.041; and for LB 0.272 ± 0.040. (B, C) 12β6 cells growing on glass coverslips in 6 well clusters were treated with DMSO, LB, or CD for 30 min, then either left untreated (B) or exposed to ISO for 15 min in the presence of transferrin-Alexa 594 (Tf, 50 μg/ml) to label early endosomes (C). Cells were fixed and β2ARs identified using a monoclonal antibody against the HA-tag. Cells were imaged using deconvolution microscopy as described. Scale bar = 10 μm. Images are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

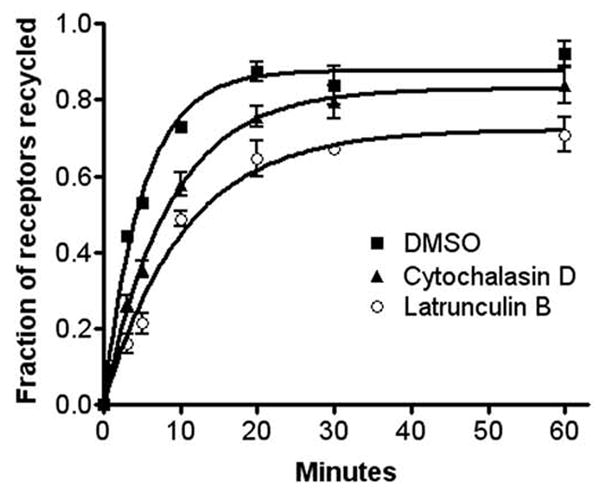

Effect of latrunculin B and cytochalasin D on β2AR recycling kinetics

Previous data has suggested that β2AR recycling is dependent upon the cortical actin cytoskeleton (14). We sought to more precisely define the effects of actin depolymerization by directly measuring the rate and extent of receptor recycling in cells growing on Matrigel coated 24-well clusters using a protocol similar to that used for previously published morphologic studies (14). 12β6 cells were treated with ISO (5 μM) for 15 min at 37°C to induce β2AR internalization to steady-state, washed, then incubated for 60 min at 4°C in DMEM-H containing DMSO, LB, or CD, as above., The media was then replaced with DMEM-H warmed to 37°C and containing the same reagents, and receptors were allowed to recycle for varying times up to 60 min. As seen in Fig. 3, treatment with LB and CD significantly reduced the rate of β2AR recycling (kr − DMSO = 0.199 ± 0.014 min−1; *LB = 0.096 ± 0.011 min−1; *CD = 0.118 ± 0.009 min−1, both treatments *p < 0.05 as compared with DMSO), but only LB significantly reduced the extent of receptor recycling (DMSO = 87.8% ± 1.7; *LB = 72.3% ± 2.7; CD = 83.1% ± 2.0, *p < 0.05 as compared with DMSO). However, in all cases, the majority of receptors eventually recycled to the cell surface.

Figure 3.

Effect of actin depolymerization on β2AR recycling. Cells were treated with ISO for 15 min to trigger receptor internalization, then washed with ice-cold DMEM-H, and incubated for 60 min at 4°C in the presence of DMSO, LB, or CD. The cells were incubated at 37°C in warm media in the continued presence of the indicated drug for varying times up to 60 min to allow receptor recycling. Surface receptor numbers were determined by incubation with [3H]CGP12177. Each point represents the mean ± s.e.m. of 3 independent experiments. The fractions of receptors that recycled were plotted as a function of time following the removal of agonist and the curves fitted as previously described (8). The zero point represents the 65–70% of receptors that internalized during agonist treatment and was not significantly different in the three groups.

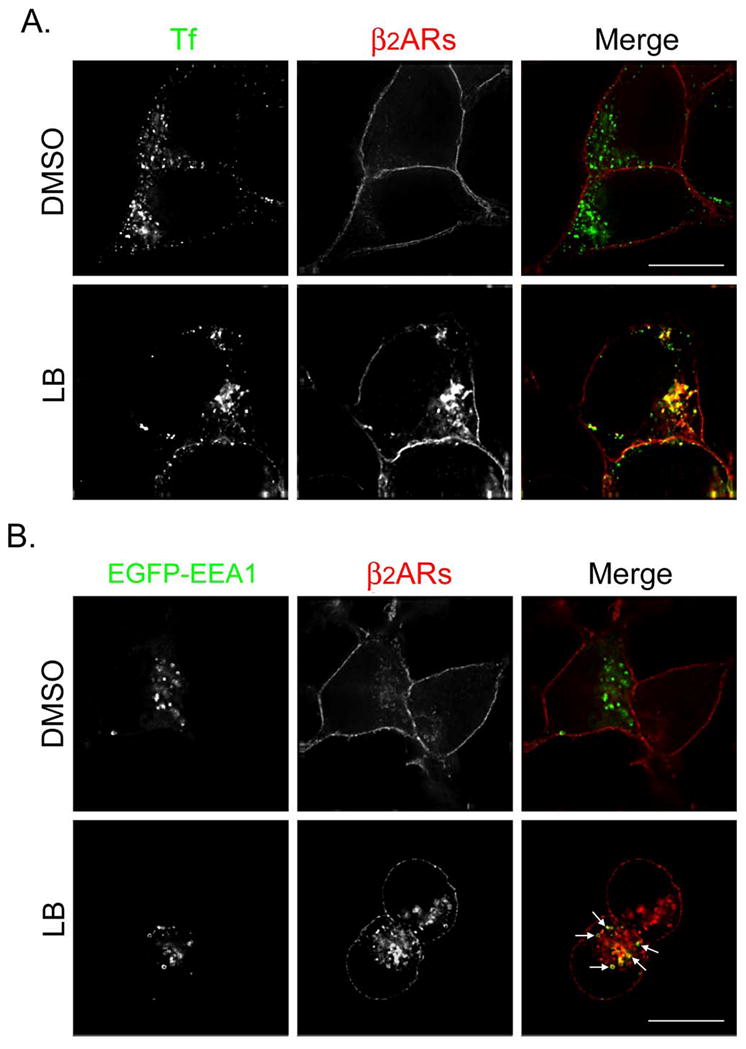

Effect of latrunculin B on β2AR trafficking

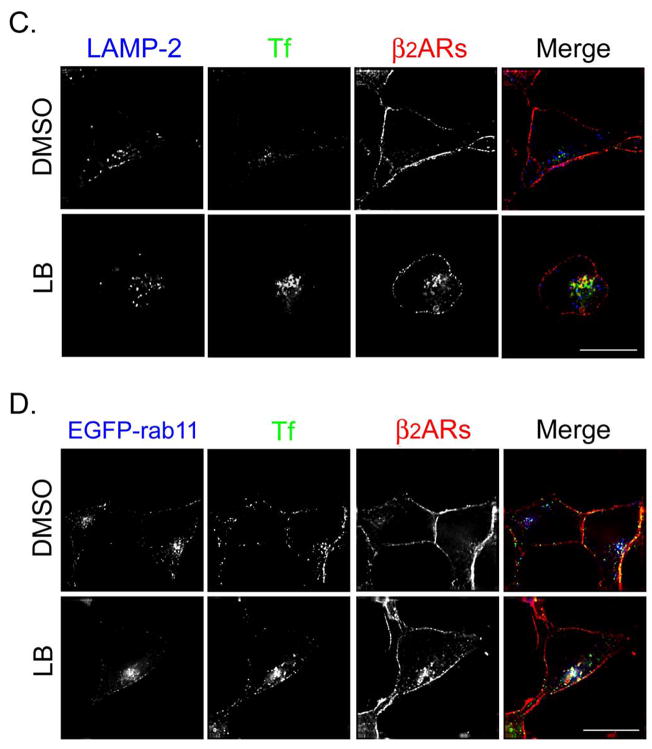

Published evidence suggests that actin depolymerization induces the sorting of endosomal β2ARs to the degradative pathway (14). Therefore, we believed it important to monitor the cellular itinerary of nonrecycled endosome-associated receptors following treatment with LB. Since our kinetic data indicated that LB was the more potent inhibitor of receptor recycling, morphologic studies were performed using that agent only. Cells were treated with ISO for 15 min to trigger β2AR internalization, washed, and incubated with either DMSO or LB for 60 min at 4°C. Cells were rapidly warmed and then incubated at 37°C in the presence of propranolol, and either DMSO or LB for the indicated times to allow receptor recycling. In Fig. 4A and 5A, cells were fed transferrin-Alexa594 during the recycling phase to nonselectively label both endocytic and recycling compartments. In Fig. 4C and D, cells were pulsed with transferrin-Alexa594 during the internalization phase and then incubated with nonfluorescent holotransferrin) during the recycling phase to selectively label the slow recycling pathway. The cells were fixed and labeled with antibodies to identify β2ARs. In some experiments, cells were transfected with plasmid DNA encoding EGFP-EEA1 to identify early endosomes (Fig. 4B), EGFP-rab11 to identify the recycling endosome (Fig. 4D), or EGFP-LAMP-1 to identify late endosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 5B). In all circumstances, after 30 min of recycling nearly all β2ARs returned to the cell surface in DMSO-treated cells, with almost no receptors localizing with EEA1 and only ~10% localizing with EGFP-rab11. In contrast, treatment with LB disrupted β2AR recycling, with nonrecycled receptors largely localizing with transferrin in both peripheral endosomes and a perinuclear compartment (percent colocalization = 57.5 ± 5.2, Fig. 4A). Approximately 23% of cellular receptors localized to EGFP-EEA1-positive peripheral endosomes (see arrows, Panel B) while ~31% localized with EGFP-rab11 in the RE (Panel D). However, fewer than 5% of receptors localized with LAMP-2 in late endosomes and lysosomes (Panel C).

Figure 4.

Latrunculin B causes β2ARs to be missorted to the recycling endosome during 30 min of recycling. (A) 12β6 cells were treated with 5 μM ISO for 15 min, washed with ice-cold DMEM-H, and maintained at 4°C for 60 min in the presence of DMSO or LB. Cells were washed with warm DMEM-H and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the presence of transferrin-Alexa594 (50 μg/ml) to label endosomes plus propranolol (5 μM) to allow receptor recycling and either DMSO or LB. Cells were fixed, labeled with monoclonal anti-HA to identify β2ARs, and visualized using deconvolution microscopy as described. Colocalization of transferrin (Tf, pseudocolored green) and β2ARs (pseudocolored red) appears yellow in the merged image. Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) Cells were transfected to transiently express EGFP-EEA1, then 48 h later treated as described above except no transferrin was added. Colocalization of β2ARs (red) and EGFP-EEA1 (green) appear yellow in the merged image. (C) 12β6 cells were treated as described above except during the internalization phase they also were pulsed with transferrin-Alexa594 (100 μg/ml) and during the recycling phase they were incubated with holotransferrin (50 μg/ml). Cells were labeled with a polyclonal antibody against the receptor’s cytoplasmic tail to identify β2ARs and an anti-LAMP-2 antibody to identify late endosomes and lysosomes. Colocalization of transferrin (Tf, pseudocolored green) and β2ARs (pseudocolored red) appears yellow in the merged image. LAMP-2 has been pseudocolored blue. Scale bar = 10 μm. (D) Cells transiently expressing EGFP-rab11 were treated as described in Panel C. Areas of colocalization of EGFP-rab11 (pseudocolored blue), transferrin (Tf, pseudocolored green) and β2ARs (pseudocolored red) appear white in the merged image. Scale bar = 10 μm. Images are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Distribution of β2ARs following 60 min of recycling in cells treated with latrunculin B (LB). Cells were treated as above except the recycling phase was extended to 60 min. (A) During the recycling phase, cells were fed transferrin-Alexa 594 (50 μg/ml) and then were labeled to identify β2ARs (pseudocolored red). Areas of colocalization of transferrin (Tf, pseudocolored green) and receptors appear yellow in the merged image. (B) Cells transiently expressing EGFP-LAMP-1 (green) were pretreated with leupeptin (100 μM) for 30 min prior to treatment as above. Following 60 min of recycling, cells were fixed and labeled to identify β2ARs (red). Areas of colocalization of the two markers appear yellow in the merged image. Scale bar = 10 μm. Images are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

The intracellular fate of nonrecycled β2ARs also was determined up to 60 min of recycling, with transferrin-Alexa594 being added during the recycling phase. To determine if receptors ultimately trafficked to the degradative pathway, cells were pretreated with the protease inhibitor leupeptin to allow receptor accumulation in late endosomes and lysosomes (12). Although most β2ARs appear to have returned to the cell surface after 60 min of recycling, nonrecycled receptors predominantly localized to vesicles containing transferrin (Fig. 5A) while only 7.2% of cellular receptors localized to EGFP-LAMP-1-positive late endosomes and lysosomes despite pretreatment with leupeptin (Fig. 5B).

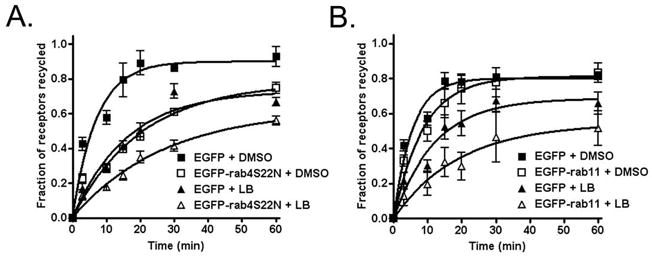

Overexpression of rab 11 slows β2AR recycling from the RE (13), while a dominant negative rab4 slows recycling from the rapid pathway (24). If LB mainly slows rapid recycling, then the combination of LB treatment and rab11 overexpression should have a synergistic effect on overall β2AR recycling, while the combination of LB and rab4 DN expression should be additive. To test this hypothesis, we treated cells transiently expressing EGFP-rab11, the dominant negative mutant EGFP-rab4S22N, or EGFP alone as a control with either DMSO or LB for 30 min prior to adding ISO (Fig. 6). Recycling was assessed by determining surface receptor levels in EGFP-positive cells using flow cytometry. Of note, the effect of LB on receptor recycling when before internalization was similar to that when LB was added following receptor internalization (compare Figs. 2 and 6) suggesting that both protocols effectively disrupt actin-dependent receptor recycling. Inhibition of the rab4 pathway following expression of EGFP-rab4S22N induced a similar effect on receptor recycling as treatment with LB, and there was some additive effect of both treatments together (Fig. 6A). Alternatively, expression of EGFP-rab11 (Fig. 6B) had only a modest effect on the rate, but none on the extent, of receptor recycling, consistent with our previously published results (13). This finding suggests that only a small fraction of β2ARs normally traffic through the RE during a brief exposure to agonist. However, upon treatment with LB, there was a marked inhibition of β2AR recycling in cells also expressing EGFP-rab11, consistent with our morphologic data showing a dramatic increase in the sorting of receptors to the RE following actin depolymerization.

Figure 6.

Effect of actin depolymerization and rab proteins on β2AR recycling. 12β6 cells transiently expressing EGFP alone, EGFP-rab4S22N, or EGFP-rab11 were labeled with anti-HA antibody to identify β2ARs, then pretreated with either LB or DMSO for 30 min at 37°C prior to adding 5 μM ISO. After 15 min of ISO exposure, cells were washed and incubated in the presence of 5 μM propranolol and either LB or DMSO for varying times up to 60 min to allow receptor recycling. We have shown that receptors pre-labeled with antibody traffic normally, and antibody does not dissociate from receptors (8). Cells were washed with ice-cold media and labeled with PerCP-conjugated rat-anti-mouse IgG1 diluted in 2% FBS (1:10) on ice for 60 min in the dark prior to harvesting and fixation with 1% PFA. Cells with a high EGFP signal (over 103) were gated and PerCP fluorescence intensity profiles of cell populations (2000–5000 gated cells per sample) were measured by flow cytometry to determine surface β2ARs. Data from 3 independent experiments were plotted using GraphPad Prism software as described above. The ratio of the experimental to control rate constants for recycling (where control = EGFP + DMSO) are as follows: EGFP-rab4S25N + DMSO = 0.35, EGFP-rab11 + DMSO = 0.63, EGFP + LB = 0.44, EGFP-rab4S22N + LB = 0.23, EGFP-rab11 + LB = 0.28.

Role of Hrs and the CART complex in actin-mediated β2AR recycling

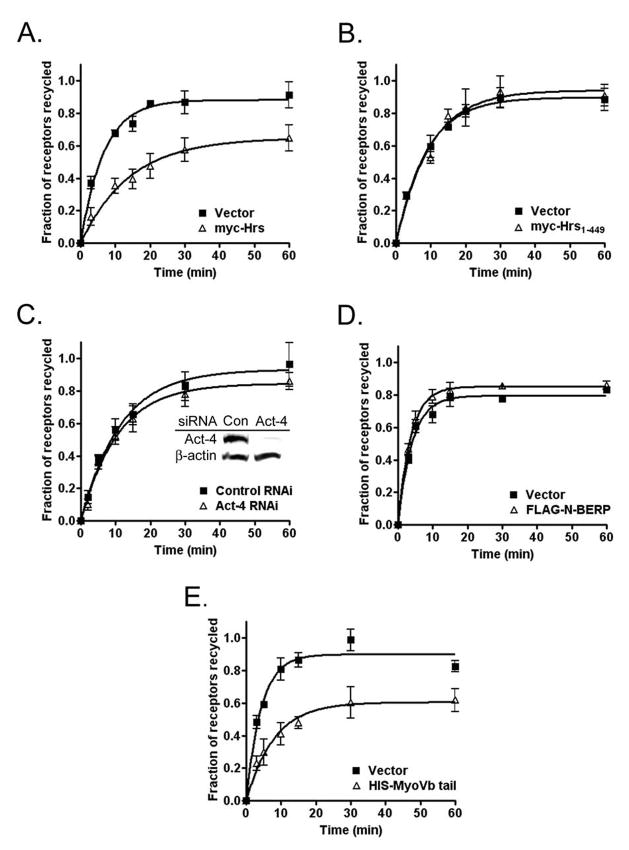

Hrs is known to regulate β2AR recycling, although the precise mechanism of this effect is unknown (11,16). Since the CART complex (Hrs/actinin-4/BERP/myosin Vb) regulates actin-dependent transferrin receptor recycling, the action of Hrs on β2AR recycling also may be mediated by the CART complex. We directly measured the recycling of β2ARs in cells transiently expressing vector or myc-Hrs (Fig. 7A), or one of the following dominant negative mutants: myc-Hrs1-449 (Fig. 7B), which interacts with actinin-4 but lacks the coiled-coil domain required for association with early endosome membranes; FLAG-N-BERP, which binds to actinin-4 but not myosin Vb (Fig. 7D); or the HIS-myosin Vb globular tail fragment, which disengages cargo from F-actin filaments (Fig. 7E) (23). We also determined receptor recycling in cells in which actinin-4 was depleted by ≈90% using RNAi (Fig. 7C, see inset for immunoblot). For transient transfection studies, receptor recycling was assessed using flow cytometry, whereas the radioligand [3H]CGP12177 was used following actinin-4 depletion. Of note, both the overexpression of myc-Hrs and the expression of the HIS-myosin Vb tail significantly inhibited β2AR recycling (Fig. 7A and 7E), with myc-Hrs and HIS-myosin Vb tail reducing the rate of receptor recycling by 53% and 48%, respectively. Alternatively, the expression of myc-Hrs1-449 or FLAG-N-BERP or the depletion of actinin-4 had no effect on receptor recycling (Fig. 7B, 7C, and 7D). The lack of effect of expression of Hrs1-449 suggests that the coiled-coil, P/Q, and/or clathrin binding domains of Hrs are required for the inhibition of recycling seen with expression the full-length protein. The lack of effect of both N-BERP expression and actinin-4 depletion on β2AR recycling suggests that this interaction is not required for receptor recycling.

Figure 7.

Hrs and myosin Vb disrupt β2AR recycling independent of the CART complex. (A, B, D, E) 12β6 cells transiently co-expressing the indicated protein and EGFP were labeled with anti-HA antibody, treated with 5 μM ISO for 15 min at 37°C, then washed and incubated in the presence of 5 μM propranolol for varying times up to 60 min to allow receptor recycling. Surface receptors were determined using flow cytometry as described in Figure 6. Data from at least 4 independent experiments were plotted using GraphPad Prism software as described above. (C) 12β6 cells were depleted of actinin-4 using RNAi (see inset for Western blot) prior to treatment with ISO and measurement of receptor recycling using [3H]CGP12177 as described in Figure 3.

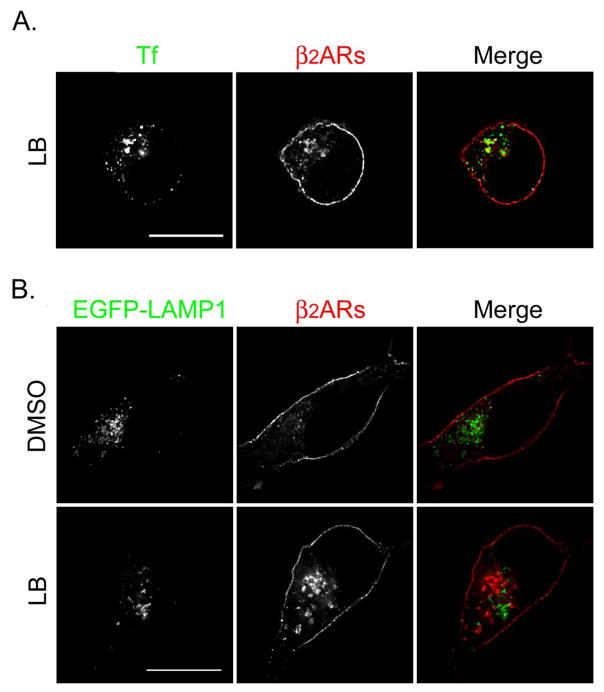

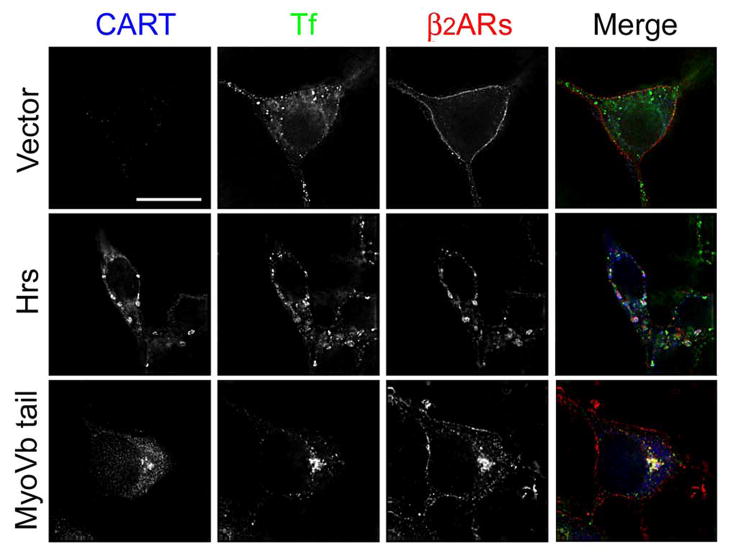

To determine if Hrs and myosin Vb have similar effects on the recycling itinerary of β2ARs, we monitored the cellular distribution of receptors using immunofluorescence microscopy. Following transfection with empty vector, myc-Hrs, or HIS-myosin Vb tail, cells were treated with ISO for 15 min, washed, and incubated at 37°C in the presence of propranolol to allow β2AR recycling. Transferrin-Alexa594 was present during both the internalization and recycling phases to label early and recycling endosomes (Fig. 8). In cells expressing empty vector, β2AR recycling was virtually complete within 15 min and most receptors localized to the cell surface. In cells expressing myc-Hrs, a significant fraction of receptors remained in peripheral vesicles that also contained Hrs and transferrin, consistent with early endosomes. In contrast, expression of the HIS-myosin Vb tail caused nonrecycled receptors to localize both to a perinuclear compartment that also contained transferrin and the myosin Vb tail fragment as well as to punctate peripheral endosomes, a phenotype similar to that observed following actin depolymerization (compare with Fig. 4A) and a pattern that persisted even after 60 min of receptor recycling (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Myosin Vb promotes the accumulation of β2ARs in the recycling endosome. Cells were transfected to transiently express pcDNA3 alone or myc-Hrs or the HIS-myosin Vb tail. Forty-eight h later, cells were treated with 5 μM ISO for 15 min, washed, and incubated for 15 min at 37°C in the presence of propranolol (5 μM) to allow β2AR recycling. Cells were fed transferrin-Alexa594 (50 μg/ml) throughout both the internalization and recycling phases to label both the endocytic and recycling pathways. Cells were fixed and labeled to identify β2ARs and the indicated CART protein (pseudocolored blue). Areas of colocalization of transferrin (Tf, pseudocolored green) and β2ARs (pseudocolored red) appear yellow in the merged image and the colocalization of all three markers appears white. Scale bar = 10 μm. Images are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

Discussion

The signaling capacity of β2ARs is regulated in part by their intracellular trafficking, with internalization into early endosomes contributing to receptor desensitization. Following a brief exposure to agonists, most internalized β2ARs recycle directly to the cell surface, thereby facilitating receptor resensitization. With repetitive rounds of receptor endocytosis and recycling, a small fraction of receptors are diverted to the RE from which they recycle slowly, while some receptors escape recycling altogether and are sorted to lysosomes for degradation (12,13,25). The specific steps that regulate the endosome sorting and recycling of β2ARs are not well understood, although roles for the endosome-associated protein Hrs and the actin cytoskeleton have been identified (11,14–16). Other proteins that are known to regulate β2AR sorting include GASP (for GPCR-associated sorting protein) (26), NSF (for N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor) (27,28), ubiquitin (29), and EBP50 (for ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM)-binding phosphoprotein-50) (14).

Published data indicate that an intact actin cytoskeleton is required for β2AR recycling and suggest that the chemical depolymerization of actin causes a missorting of receptors to lysosomes (14). However, this conclusion was based on morphologic data in the absence of localization with specific compartment markers and without measurements of β2AR recycling rates. In the current study, we show that while the actin cytoskeleton regulates the trafficking itinerary used by β2ARs during recycling and the chemical disruption of actin causes a significant slowing in the rate of β2AR recycling, most receptors eventually recycle to the cell surface by 60 min after agonist removal. Further, our data indicate that the degradative pathway is not the main destination of nonrecycled receptors. Instead, our finding of synergy in the effect of actin depolymerization and overexpressing rab11 on receptor recycling indicates that disrupting actin causes receptors to be shunted to the slow recycling pathway via the RE, from which they recycle in a rab11-dependent manner. Further, that LB and the expression of a dominant negative rab4 (rabS22N) were only additive in their effect on recycling suggests that they both act to inhibit the rapid recycling pathway, although neither treatment individually is completely inhibitory.

We cannot rule out the possibility that actin depolymerization has some inhibitory effect on β2AR recycling from the recycling endosome itself. Indeed, the recycling endosome is rich in both actin and the t-SNARE syntaxin 4, which also interacts with actin filaments, making this pathway a potential target for the actions of actin disrupting agents (30,31). However, we believe that the role of actin in this pathway in HEK293 cells is unlikely to be of great importance given the substantial syngergism we observed between rab11 overexpression and LB treatment.

Given the role of Hrs as a regulator of β2AR recycling (11,16), we believed it important to determine if Hrs exerts its effects through the CART protein complex, which is known to link endosome-associated transferrin receptors to the actin cytoskeleton (23). The overexpression of myc-Hrs inhibited β2AR recycling from peripheral early endosomes (Fig. 7, 8), consistent with recently published data (11). Although the effect of Hrs on β2AR appears to be dependent on a signal localized within the receptor’s cytoplasmic tail (16), altering the cellular expression of Hrs also regulates the recycling of other GPCRs, including the protease-activated receptor 2 and calcitonin receptor-like receptor, suggesting that these effects are not specific to the β2AR (32). Based on studies of transferrin receptor trafficking, we expected that maneuvers that disrupt CART complex interactions with endosomal membranes or that dissociate Hrs from the actin cytoskeleton would also impair β2AR recycling and cause their missorting to the recycling endosome (23). Instead, expression of the Hrs1–449 mutant, which cannot bind endosomal membranes, or the depletion of actinin-4 or expression of N-BERP, which disrupts the CART complex, had no effect on receptor recycling. This finding indicates that Hrs does not regulate β2AR recycling through the CART complex and that Hrs must be associated with endosome membranes to exert its effects on receptor recycling. In contrast, expression of the myosin Vb tail, which cannot interact with actin and serves as a dominant negative mutant, markedly impaired the recycling of β2ARs and caused their missorting to a perinuclear compartment consistent with the RE, a trafficking phenotype similar to that seen in latrunculin B-treated cells (compare Figs. 4 and 8).

Myosin Vb is one of the three members of the myosin V protein family. These proteins are progressive motors that walk hand-over-hand in 37 nm steps along actin filaments, an interaction mediated by the myosin V motor (head) domain (33). In addition to its known interaction with BERP, the tail domain of myosin Vb also interacts with GTP-bound rab11 and with the rab11-interacting protein, rab11-FIP2 (34). Myosin Vb has been implicated as a regulator of the recycling of transferrin receptors and the AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunit GluR1, as well as that of the M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor and the chemokine receptor, CXCR2, both members of the GPCR superfamily (34–37). Expression of the myosin Vb tail fragment impairs the recycling of these receptors, causing them to accumulate in the pericentriolar RE. Based on these findings, it has been suggested that myosin Vb regulates recycling from the RE to the cell surface. However, the β2AR differs from these other receptors in that only a small fraction of β2ARs utilize the slow recycling pathway via the RE following a brief exposure to agonist (13). Instead, most β2ARs recycle via the rapidly recycling pathway directly to the cell surface. Thus, our results are more consistent with a recently proposed model based on the chemical inhibition of myosin Vb (38). This model predicts that myosin Vb functions by supporting the anterograde transport of receptors (i.e., early endosomes to cell surface) and negatively regulating their retrograde transport driven by dynein (i.e., early endosomes to recycling endosomes). Expression of the myosin Vb tail displaces endogenous myosin, thereby impairing anterograde transport and preventing the myosin Vb inhibition of dynein and allowing receptors to traffic retrograde to the RE. Thus, expression of the myosin Vb tail should cause β2ARs to remain localized to peripheral early endosomes as well as to accumulate in the RE, consistent with our findings demonstrated in Fig. 8. However, our data cannot rule-out an additional role for myosin Vb in regulating β2AR recycling from the RE itself.

It is unclear how β2AR recycling is linked to myosin Vb, but it is possible that this effect is mediated through the interaction of myosin Vb with rab11, either directly or indirectly through rab11-FIP2. We have shown that rab11 regulates β2AR recycling, and expression of the rab11S25N mutant, which cannot bind myosin Vb (36), inhibits the rapid recycling of receptors from early endosomes (13). Thus, it is possible that the expression of this rab11 mutant may prevent the interaction of myosin Vb with endosomal membranes or with the actin cytoskeleton, uncoupling endosome-associated β2ARs from actin filaments. It also is possible that β2ARs and myosin Vb are linked by an adapter protein, such as EBP50, which interacts with receptors via a cytoplasmic terminus PDZ domain and which is required for β2AR recycling (14). Such a mechanism has been proposed to explain the role of myosin Vb in the recycling of glutamate receptor recycling in neurons (37). Whatever the mechanism, our findings indicate that myosin Vb regulates the actin-dependent recycling of β2ARs from directly early endosomes to the cell surface, which occurs independently of Hrs and the CART complex.

A somewhat surprising finding in this study is that β2AR internalization in HEK293 cells was not dependent on the actin cytoskeleton, as demonstrated both by radioligand binding and immunofluorescence microscopy. To depolymerize the actin cytoskeleton, we used concentrations of two actin depolymerizing agents that clearly disrupted actin localization, cell morphology, and β2AR recycling. This result is in marked contrast to recent reported data in HEK293 cells indicating that β2AR internalization requires an intact and dynamic actin cytoskeleton (21). However, in that report, receptor internalization was assessed using transiently expressed β2ARs which in most cases contained a C-terminal fluorescent (YFP)-tag. In the current study, we utilized stably expressed receptors that were tagged only at the N-terminus. Stably expressed receptors internalize much more efficiently as compared with transiently expressed receptors, suggesting that they are better coupled to arrestin proteins (6). For the thromboxane A2 receptor, overexpressing arrestin 3 can antagonize the internalization defect induced by latrunculin B treatment, suggesting the presence of an actin-independent arrestin-mediated internalization pathway (20). Further confounding the previous results, the addition of a C-terminus tag may disrupt β2AR interactions with proteins that may be required for proper receptor trafficking (14,28,39). Finally, our data are in agreement with two other studies in which treatment with actin depolymerizing agents had no effect on β2AR internalization in A431 cells (15) or in HEK293 cells (20). Thus, we believe that the internalization of stably expressed β2ARs lacking a C-terminus tag is not dependent on the actin cytoskeleton.

In conclusion, our findings indicate a role for the actin cytoskeleton and the motor protein myosin Vb in the regulation of β2AR recycling. It is likely that actin assembly governs which recycling route is utilized by receptors rather than serving as a regulator of sorting to the degradative pathway. Among GPCRs, the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 are known to recycle in an actin-dependent manner (40), however the exact pathways disrupted are unknown. Further, the inhibition of CXCR2 recycling following disruption of actin polymerization with cytochalasin D or expression of the myosin Vb tail also impairs receptor resensitization and receptor-mediated chemotaxis (34,40). Given the functional implications of β2AR trafficking, it is probable that the actin cytoskeleton and myosin Vb are also key regulators of β2AR activity.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and materials

12β6 cells (a gift of B. Kobilka, Stanford, CA) were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 400 μg/ml Geneticin (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). This cell line was derived from HEK293 cells and expresses human β2ARs with an N-terminal HA-tag at a level of 300,000/cell (41,42). Geneticin was removed from the media prior to experiments. Mouse monoclonal antibodies against the HA-tag (mHA.11) and LAMP-2 were obtained from Covance (Berkeley, CA) and BD Transduction Laboratories (Franklin Lakes, NJ), respectively. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the terminal 15 amino acids of the β2AR C-terminus (α-CT), myc-epitope tag, the 6-His tag, and actinin-4 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA), Covance Research Products (Berkeley, CA), and Abnova (Taipei City, Taiwan), respectively. Species-appropriate goat secondary antibodies, transferrin conjugated to Alexa594, and phalloidin-Texas Red conjugate were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). FuGene 6 transfection reagent was obtained from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Basel) and Lipofectamine2000 was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Latrunculin B was purchased from Alexis Corporation (San Diego, CA). Holotransferrin was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). The anti-mouse peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-conjugated antibody and Matrigel were obtained from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ). The plasmid DNA encoding the enhanced the enhanced green fluorescent protein-rab11 chimera (EGFP-rab11) was kindly provided by Dr. Angela Wandinger-Ness (Albuquerque, N.M.), EGFP-EEA1 by Dr. Sylvia Corvera (Worcester, MA), and EGFP-LAMP-1 by Dr. Jack Rohrer (Zurich). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted. Latrunculin B and cytochalasin D were solubilized in DMSO at 1000X concentrations and stored in aliquots at −20°C prior to use.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Following the indicated treatments, cells were washed with PBS containing 1.2% sucrose (PBSS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBSS, as previously described (12). For labeling cells we used the following concentrations of antibodies: mHA.11, 5μg/ml; anti-LAMP-2, 5 μg/ml; polyclonal anti-β2AR C-terminus, 2 μg/ml; Alexa488- and Alexa647-anti-mouse IgG, 1:200 dilution; and Alexa-594 and 647 anti-rabbit IgG, 1:200 dilution. Phalloidin-Texas Red was applied at a concentration of 1 unit per coverslip per manufacturer’s recommendation. The coverslips were mounted in Mowiol and viewed using a DeltaVision deconvolution microscopy system (Applied Precision Inc., Issaquah, WA) equipped with a Zeiss Axiovert microscope. Imaging was performed using a Zeiss 100X (1.4 numerical aperture) oil immersion lens and sections were imaged at an optical depth of 150 nm in the z-plane. Images were optimized using DeltaVision deconvolution software and transferred to Adobe Photoshop 6.0 for pseudocoloring and the production of final figures. For consistency, in all images β2ARs have been pseudocolored red and transferrin is shown in green, such that their colocalization appears yellow.

Measurement of β2AR internalization

To improve cell adherence, 12β6 cells were grown on Matrigel-coated 24-well plates for 72 h at 37°C. Cells were then pretreated with DMSO (1:1000), LB (10 μg/ml), or CD (2 μM) for 30 min prior to agonist exposure. Cells were treated with to 5 μM isoproterenol (ISO) for varying times up to 30 min to induce receptor internalization. The cells were chilled and surface receptors measured by incubation in DMEM with 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4, DMEM-H) containing 6 nM [3H]CGP12177 at 0°C for 2 h, followed by washing with cold DMEM-H. The monolayers were harvested in a solution containing 1% SDS and 1% NP-40, and the lysates counted by scintillation spectroscopy, with binding at each time point being measured in triplicate. The fraction of receptors on the cell surface was plotted versus time of agonist treatment, and the curves fitted by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism software (version 4.0) and internalization rate constants determined as previously described (8). Rate constants are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. of three separate experiments.

For morphologic studies of β2AR internalization, 12β6 cells growing on Matrigel-coated glass coverslips were treated with DMSO or the indicated actin inhibitor as above and exposed to ISO for 15 min to trigger β2AR internalization. During the agonist incubation, cells were pulsed with transferrin-Alexa594 (50 μg/ml) to label early endosomes. Cells were fixed, labeled for β2ARs using mHA.11 antibody, and imaged as described above.

Measurement of β2AR recycling using [3H]CGP12177

12β6 cells were grown on Matrigel-coated 24 well clusters as described above. Cells were treated with ISO (5 μM) for 15 min at 37°C cells, washed extensively, and incubated in cold DMEM-H chilled to 4°C and containing either DMSO, LB, or CD for 60 min. The chilled media was replaced with DMEM-H prewarmed to 37°C and containing DMSO or the indicated inhibitor to allow recycling for varying times up to 60 min. Surface β2ARs were measured as described following incubation with [3H]CGP12177 and plotted versus the time of recycling. The curves were fitted by nonlinear regression and recycling rate constants determined using GraphPad Prism software. Rate constants are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. of three separate experiments.

Subcellular localization of β2ARs following treatment with latrunculin B

12β6 cells growing on Matrigel-coated 22 mm glass coverslips in 6-well clusters were serum-starved for 2–3 h prior to treatment. Cells were treated with ISO (5 μM) for 15 min to induce β2AR internalization, extensively washed with ice-cold DMEM-H, then incubated at 4°C for 60 min in the presence of either DMSO or latrunculin B, as described above. Cells were rapidly warmed and placed in serum-free media in the presence of the indicated inhibitor along with propranolol (5 μM) for varying times up to 60 min to allow recycling. For some studies of β2AR localization, transferrin-Alexa594 was added as indicated in the figure legends. For some experiments, cells were transfected to transiently express EGFP-EEA1 to identify early endosomes, EGFP-LAMP-1 to identify late endosomes and lysosomes, or with EGFP-rab11 to identify the RE using FuGene 6 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s instruction, with a DNA to FuGene 6 ratio of 2 μg/3 μl. The transfection mixture remained on cells for 48 h, at which time the cells were treated as indicated in the figure legends. To ensure that the Matrigel coating did not itself alter β2AR trafficking, some experiments were repeated using poly-D-lysine coated coverslips with similar results (data not shown).

Quantification of the localization of nonrecycled β2ARs was determined using MetaMorph Premier software. Quantification of overlap with compartment markers was performed following the construction of a binary image for each channel based on the merged image. The extent of colocalization was determined from three independent sections from each cell. The final values reflect the means±s.e.m. for 3–4 cells from 2 or more separate experiments.

Measurement of β2AR recycling using flow cytometry

12β6 cells growing on 12-well plates were transfected with plasmid DNA encoding EGFP, EGFP-rab11, or EGFPrab4S22N. For studies of the CART proteins, cells were transfected with both EGFP and either myc-Hrs, myc-Hrs1-449, FLAG-BERP1-485 (FLAG-N-BERP), or the HIS-myosin Vb tail fragment at a DNA ratio of 1:9 (total DNA = 1 μg). Twenty-four h later, the media was replaced with DMEM-2% FBS containing anti-HA antibody (1:200 dilution) for 1 h to label β2ARs. Cells were washed using DMEM-H and allowed to equilibrate in DMEM-H for 1 h on a 37°C heating block prior to experimentation. For some experiments, cells were treated with DMSO or LB for 30 min as described above prior to adding ISO. Cells then were treated with 5 μM ISO for 15 min at 37°C, washed, and incubated in the presence of 5 μM propranolol for varying times up to 60 min to allow receptor recycling. For studies of actin disruption, DMSO or LB also was included during the recycling phase. Cells were washed with ice-cold media and labeled with PerCP-conjugated rat-anti-mouse IgG1 diluted in 2% FBS (1:10) on ice for 60 min in the dark prior to harvesting and fixation with 1% PFA. Cells with a high EGFP signal (over 103) were gated and PerCP fluorescence intensity profiles of cell populations (2000–5000 gated cells per sample) were measured by flow cytometry using a Becton-Dickinson FACS instrument to determine surface β2ARs. Untransfected 12β6 cells without or with antibody labeling were used as negative and positive controls. Data from at least 3 independent experiments were plotted using Graphpad Prism software as described above, and the results were similar to the recycling measurements using [3H]CGP12177.

Actinin-4 depletion using RNAi

12β6 cells were seeded into 60 mm dishes at a density of 4×105 cells/well. After 24 and 48 h, cells were transfected with 200 nM of either actinin-4 SMARTpool siRNA (ON-TARGETplus, Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) or non-targeting SMARTpool control siRNA using Lipofectamine2000. Five h after the second transfection, the cells were reseeded into 24-well plates for recycling and 6-well plates for Western blotting. β2AR recycling was determined 24 h after the second transfection using [3H]CGP12177, as described above.

To determine the extent of actinin-4 depletion, cells were solubilzed in RIPA buffer and samples (10 μg protein) were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (4–20% gels) and transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblotting. The membranes were probed with a polyclonal antibody against actinin-4 at a dilution of 1:500 and bound antibodies were detected by chemiluminescence (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL) and quantified by densitometry. Membranes were stripped and reprobed using a β-actin antibody (Sigma) as a loading control.

CART complex and β2AR trafficking

12β6 cells growing on poly-D-lysine glass coverslips were transfected with 2 μg of plasmid DNA encoding empty vector, myc-Hrs, or the HIS-myosin Vb tail fragment using Fugene 6 as described. Forty-eight h later, cells were serum-starved for 2 h and then treated with 5 μM ISO for 15 min, washed, and incubated in warm media containing 5 μM propranolol for 15 min to allow receptor recycling. Transferrin-Alexa594 (50 μg/ml) was added during both the internalization and recycling phases to label early and recycling endosomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs. Angela Wandinger-Ness, Sylvia Corvera, and Jack Rohrer for kindly providing plasmid DNAs. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL64934 (to R.H.M.) and MH058920 (to A.J.B.) and by American Heart Association grant 0455072Y (to B.J.K.).

Abbreviations

- β2AR

β2-adrenergic receptor

- LB

latrunculin B

- CD

cytochalasin D

- ISO

isoproterenol

- PerCP

peridinin chlorophyll protein

- Hrs

hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate

- CART complex

cytoskeleton-associated recycling and transport complex

- RE

recycling endosome

References

- 1.Benovic JL, Strasser RH, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-adrenergic receptor kinase: identification of a novel protein kinase that phosphorylates the agonist-occupied form of the receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:2797–2801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitcher J, Lohse MJ, Codina J, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Desensitization of the isolated β2-adrenergic receptor by β-adrenergic receptor kinase, cAMP-dependent protein kinase, and protein kinase-C occurs via distinct molecular mechanisms. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3193–3197. doi: 10.1021/bi00127a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tran TM, Friedman J, Qunaibi E, Baameur F, Moore RH, Clark RB. Characterization of agonist stimulation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and G protein-coupled receptor kinase phosphorylation of the beta2-adrenergic receptor using phosphoserine-specific antibodies. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:196–206. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman OB, Jr, Krupnick JG, Santini F, Gurevich VV, Penn RB, Gagnon AW, Keen JH, Benovic JL. Beta-arrestin acts as a clathrin adaptor in endocytosis of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 1996;383:447–450. doi: 10.1038/383447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. The molecular acrobatics of arrestin activation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaughan DJ, Millman EE, Godines V, Friedman J, Tran TM, Dai W, Knoll BJ, Clark RB, Moore RH. Role of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase site serine cluster in beta2-adrenergic receptor internalization, desensitization, and beta-arrestin translocation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7684–7692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson SS, Downey WE, III, Colapietro AM, Barak LS, Menard L, Caron MG. Role of beta-arrestin in mediating agonist-promoted G protein-coupled receptor internalization. Science. 1996;271:363–366. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison KJ, Moore RH, Carsrud NDV, Millman EE, Trial J, Clark RB, Barber R, Tuvim M, Dickey BF, Knoll BJ. Repetitive endocytosis and recycling of the β2-adrenergic receptor during agonist-induced steady-state redistribution. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:692–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu SS, Lefkowitz RJ, Hausdorff WP. β-adrenergic receptor sequestration - a potential mechanism of receptor resensitization. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:337–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pippig S, Andexinger S, Lohse MJ. Sequestration and recycling of β2-adrenergic receptors permit receptor resensitization. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;47:666–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanyaloglu AC, McCullagh E, von Zastrow M. Essential role of Hrs in a recycling mechanism mediating functional resensitization of cell signaling. EMBO J. 2005;24:2265–2283. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore RH, Tuffaha A, Millman EE, Hall HS, Dai W, Dickey BF, Knoll BJ. Agonist-induced sorting of human β2-adrenergic receptors to lysosomes during downregulation. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:329–338. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore RH, Millman EE, Alpizar-Foster E, Dai W, Knoll BJ. Rab11 regulates the recycling and lysosome targeting of beta2-adrenergic receptors. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3107–3117. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao TT, Deacon HW, Reczek D, Bretscher A, von Zastrow M. A kinase-regulated PDZ-domain interaction controls endocytic sorting of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 1999;401:286–289. doi: 10.1038/45816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shumay E, Gavi S, Wang HY, Malbon CC. Trafficking of beta2-adrenergic receptors: insulin and beta-agonists regulate internalization by distinct cytoskeletal pathways. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:593–600. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanyaloglu AC, von Zastrow M. A novel sorting sequence in the beta2-adrenergic receptor switches recycling from default to the Hrs-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3095–3104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamaze C, Fujimoto LM, Yin HL, Schmid SL. The actin cytoskeleton is required for reeptor-mediated endocytosis in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20332–20335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujimoto LM, Roth R, Heuser JE, Schmid SL. Actin assembly plays a variable, but not obligatory role in receptor-mediated endocytosis in mammalian cells. Traffic. 2000;1:161–171. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunn JA, Wong H, Rozengurt E, Walsh JH. Requirement of cortical actin organization for bombesin, endothelin, and EGF receptor internalization. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C2019–C2027. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.6.C2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laroche G, Rochdi MD, Laporte SA, Parent JL. Involvement of actin in agonist-induced endocytosis of the G protein-coupled receptor for thromboxane A2: overcoming of actin disruption by arrestin-3 but not arrestin-2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23215–23224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volovyk ZM, Wolf MJ, Naga Prasad SV, Rockman HA. Agonist-stimulated beta -adrenergic receptor internalization requires dynamic cytoskeletal actin turnover. J Biol Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511435200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheff DR, Kroschewski R, Mellman I. Actin dependence of polarized receptor recycling in Madin-Darby canine kidney cell endosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:262–275. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-07-0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan Q, Sun W, Kujala P, Lotfi Y, Vida TA, Bean AJ. CART: an Hrs/actinin-4/BERP/myosin V protein complex required for efficient receptor recycling. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2470–2482. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCaffrey MW, Bielli A, Cantalupo G, Mora S, Roberti V, Santillo M, Drummond F, Bucci C. Rab4 affects both recycling and degradative endosomal trafficking. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kallal L, Gagnon AW, Penn RB, Benovic JL. Visualization of agonist-induced sequestration and down-regulation of a green fluorescent protein-tagged β2-adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:322–328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whistler JL, Enquist J, Marley A, Fong J, Gladher F, Tsuruda P, Murray SR, von Zastrow M. Modulation of postendocytic sorting of G protein-coupled receptors. Science. 2002;297:615–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1073308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Lauffer B, von ZM, Kobilka BK, Xiang Y. N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor regulates beta2 adrenoceptor trafficking and signaling in cardiomyocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:429–439. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.037747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cong M, Perry SJ, Hu LA, Hanson PI, Claing A, Lefkowitz RJ. Binding of the beta2 adrenergic receptor to N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor regulates receptor recycling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45145–45152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shenoy SK, McDonald PH, Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of receptor fate by ubiquitination of activated beta 2-adrenergic receptor and beta-arrestin. Science. 2001;294:1307–1313. doi: 10.1126/science.1063866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trischler M, Stoorvogel W, Ullrich O. Biochemical analysis of distinct Rab5- and Rab11-positive endosomes along the transferrin pathway. J Cell Sci. 1999;112 ( Pt 24):4773–4783. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.24.4773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Band AM, Ali H, Vartiainen MK, Welti S, Lappalainen P, Olkkonen VM, Kuismanen E. Endogenous plasma membrane t-SNARE syntaxin 4 is present in rab11 positive endosomal membranes and associates with cortical actin cytoskeleton. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:513–519. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasdemir B, Bunnett NW, Cottrell GS. Hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (Hrs) mediates post-endocytic trafficking of protease-activated receptor 2 and calcitonin receptor-like receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29646–29657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702974200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yildiz A, Forkey JN, McKinney SA, Ha T, Goldman YE, Selvin PR. Myosin V walks hand-overhand: single fluorophore imaging with 1.5-nm localization. Science. 2003;300:2061–2065. doi: 10.1126/science.1084398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan GH, Lapierre LA, Goldenring JR, Sai J, Richmond A. Rab11-family interacting protein 2 and myosin Vb are required for CXCR2 recycling and receptor-mediated chemotaxis. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2456–2469. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lapierre LA, Kumar R, Hales CM, Navarre J, Bhartur SG, Burnette JO, Provance DW, Jr, Mercer JA, Bahler M, Goldenring JR. Myosin vb is associated with plasma membrane recycling systems. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1843–1857. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volpicelli LA, Lah JJ, Fang G, Goldenring JR, Levey AI. Rab11a and myosin Vb regulate recycling of the M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9776–9784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09776.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lise MF, Wong TP, Trinh A, Hines RM, Liu L, Kang R, Hines DJ, Lu J, Goldenring JR, Wang YT, El-Husseini A. Involvement of myosin Vb in glutamate receptor trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3669–3678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511725200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Provance DW, Jr, Gourley CR, Silan CM, Cameron LC, Shokat KM, Goldenring JR, Shah K, Gillespie PG, Mercer JA. Chemical-genetic inhibition of a sensitized mutant myosin Vb demonstrates a role in peripheral-pericentriolar membrane traffic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1868–1873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305895101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLean AJ, Milligan G. Ligand regulation of green fluorescent protein-tagged forms of the human beta(1)- and beta(2)-adrenoceptors; comparisons with the unmodified receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1825–1832. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zaslaver A, Feniger-Barish R, Ben-Baruch A. Actin filaments are involved in the regulation of trafficking of two closely related chemokine receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2. J Immunol. 2001;166:1272–1284. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Zastrow M, Kobilka BK. Ligand-regulated internalization and recycling of humanβ2- adrenergic receptors between the plasma membrane and endosomes containing transferrin receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:3530–3538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore RH, Sadovnikoff N, Hoffenberg S, Liu S, Woodford P, Angelides K, Trial J, Carsrud NDV, Dickey BF, Knoll BJ. Ligand-stimulated β2-adrenergic receptor internalization via the constitutive endocytic pathway into rab5-containing endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 1995;108:2983–2991. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.9.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]