Abstract

Transient Receptor Potential A1 (TRPA1) is a nonselective cation channel, preferentially expressed on a subset of nociceptive sensory neurons, that is activated by a variety of reactive irritants via the covalent modification of cysteine residues. Excessive nitric oxide during inflammation (nitrative stress), leads to the nitration of phospholipids, resulting in the formation of highly reactive cysteine modifying agents, such as nitrooleic acid (9-OA-NO2). Using calcium imaging and electrophysiology, we have shown that 9-OA-NO2 activates human TRPA1 channels (EC50, 1 μM), whereas oleic acid had no effect on TRPA1. 9-OA-NO2 failed to activate TRPA1 in which the cysteines at positions 619, 639, and 663 and the lysine at 708 had been mutated. TRPA1 activation by 9-OA-NO2 was not inhibited by the NO scavenger carboxy-PTIO. 9-OA-NO2 had no effect on another nociceptive-specific ion channel, TRPV1. 9-OA-NO2 activated a subset of mouse vagal and trigeminal sensory neurons, which also responded to the TRPA1 agonist allyl isothiocyanate and the TRPV1 agonist capsaicin. 9-OA-NO2 failed to activate neurons derived from TRPA1(-/-) mice. The action of 9-OA-NO2 at nociceptive nerve terminals was investigated using an ex vivo extracellular recording preparation of individual bronchopulmonary C fibers in the mouse. 9-OA-NO2 evoked robust action potential discharge from capsaicin-sensitive fibers with slow conduction velocities (0.4-0.7 m/s), which was inhibited by the TRPA1 antagonist AP-18. These data demonstrate that nitrooleic acid, a product of nitrative stress, can induce substantial nociceptive nerve activation through the selective and direct activation of TRPA1 channels.

Oxidative stress and nitrative stress have been implicated as contributing to acute and chronic inflammation (Radi, 2004; Szabó et al., 2007; Valko et al., 2007). Nitric oxide (NO) is an endogenous mediator with multiple cellular functions that is produced by many cell types including vascular endothelium, neutrophils, fibroblasts, and nerves (Bian and Murad, 2003). NO, generated from l-arginine by NO synthases (NOS), reacts with the reactive oxygen species (ROS) superoxide—which is formed through multiple pathways in inflammation, including NADPH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, and perverted mitochondrial function—to produce the reactive nitrogen species (RNS), peroxynitrite (ONOO-), and nitrogen dioxide (*NO2). RNS are potent inflammatory molecules that can react with lipids, proteins, and DNA (Szabóet al., 2007). Within membranes, where the hydrophobic environment maximizes RNS production (Möller et al., 2007), RNS react with unsaturated fatty acids (e.g., oleic acid), causing the addition of an NO2 group (nitration) (Freeman et al., 2008; Jain et al., 2008; Trostchansky and Rubbo, 2008). Nitrated fatty acids (e.g., nitrooleic acid) are highly reactive electrophilic compounds that can modulate a variety of cellular targets, including thiol residues and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (Freeman et al., 2008; Trostchansky and Rubbo, 2008).

Nitrated fatty acids are detectable in vitro after exposure of fatty acids to RNS donors (O'Donnell et al., 1999; Jain et al., 2008). Nitrated fatty acids have been measured in human plasma and red blood cells, with total nitrooleic acid (OA-NO2) and total nitrolinoleic acid concentrations in plasma of 920 and 630 nM, respectively (Baker et al., 2005). It is noteworthy that, unlike oxidative stress-produced reactive unsaturated aldehydes such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4HNE) that tend to break off from the phospholipid during peroxidation (Gardner, 1989), 32% of OA-NO2 in plasma and 72% in packed red blood cells is esterified (bound within phospholipid) (Baker et al., 2005). The intriguing possibility exists that esterified nitrated fatty acids represent a sink of bioactive mediators produced during nitrative stress that can induce subsequent cellular functions after liberation from the membrane by phospholipase A2 (Jain et al., 2008).

Inflammation elicits pain and reflexes as a result of the activation of somatosensory and visceral nociceptive sensory nerves. Recently, a member of the transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channel family termed TRPA1 has been demonstrated preferentially on nociceptive sensory nerves and is activated by irritants such as allyl isothiocyanate (AITC), cinnamaldehyde, bradykinin, and phytocannabinoids (Bandell et al., 2004; Jordt et al., 2004; Bautista et al., 2006; De Petrocellis et al., 2008). ROS and reactive lipid peroxidation products have been shown to activate nociceptive neurons via TRPA1 (Bautista et al., 2006; Macpherson et al., 2007b; Trevisani et al., 2007; Andersson et al., 2008; Taylor-Clark et al., 2008a,b), probably via the direct covalent modification of key N-terminal cysteine groups (Hinman et al., 2006; Macpherson et al., 2007a; Trevisani et al., 2007). Given that the nitro group (NO2) is one of the strongest electron-with-drawing groups known, and given that the rate constants for cysteine adduction by nitrated fatty acids exceed those of lipid peroxidation products (Baker et al., 2007), we predict that the reactive products of nitrative stress represent a group of highly potent endogenous TRPA1 activators, such that their production during inflammation may significantly enhance nociceptors activation.

Materials and Methods

All experiments were approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee or conducted according to the requirements of the United Kingdom Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986) and strictly conformed to the ethical standards of GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals as appropriate.

HEK293 Cell Culture. Wild-type HEK293 cells, cells stably expressing human TRPA1 (hTRPA1-HEK), or cells stably expressing human TRPV1 (hTRPV1-HEK) were used in this study, as described previously (Taylor-Clark et al., 2008b). Cells were maintained in an incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (containing 110 μg/liter pyruvate) supplemented with 10% FBS and 500 mg/ml G418 (Geneticin) as a selection agent. Cells were removed from their culture flasks by treatment with Accutase (Sigma), then plated onto poly-d-lysine-coated cover slips and incubated at 37°C for >1 h before experimentation.

hTRPA1-3C/K-Q Mutant. cDNA (1.6 μg/ml) for hTRPA1 and hTRPA1-3C/K-Q (Cys619, Cys639, and Cys663 mutated to serines; Lys708 mutated to glutamine) (Hinman et al., 2006) was expressed in HEK293 cells using GenJet In Vitro DNA Transfection Reagent (SignaGen Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD).

TRPA1(-/-)/TRPV1(-/-) Mice. TRPA1(-/-) mice (Taylor-Clark et al., 2008a) were successfully bred with TRPV1(-/-) mice (Davis et al., 2000), yielding normal Mendelian numbers of offspring. Those mice that were homozygous deficient in both TRPA1 and TRPV1 were used in this study.

Dissociation of Mouse Sensory Ganglia. Mouse vagal and trigeminal ganglia were isolated and enzymatically dissociated from wild-type C57BL/6J mice, TRPA1(-/-) mice, and TRPA1(-/-)/TRPV1(-/-) mice using methods described previously (Taylor-Clark et al., 2008a,b). Isolated neurons were plated onto poly-d-lysine- and laminin-coated coverslips and used within 24 h.

Calcium Imaging. HEK293-covered coverslips were loaded with Fura 2 acetyoxymethyl ester (Fura-2AM; 8 μM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (containing 110 mg/liter pyruvate) supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated (40 min, 37°C, 5% CO2). Neuron-covered coverslips were loaded with Fura-2 AM (8 μM) in L-15 media containing 20% FBS and incubated (40 min, 37°C). For imaging, the coverslip was placed in a custom-built chamber (bath volume of 600 μl) and superfused at 4 ml/min with Locke solution (34°C): 136 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 14.3 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM dextrose (gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2, pH 7.3-7.4) for 15 min before and throughout each experiment by an infusion pump. Changes in intracellular free calcium concentration (intracellular [Ca2+]free) were measured by digital microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY) equipped with in-house equipment for ratiometric recording of single cells. The field of cells was monitored by sequential dual excitation, at 352 and 380 nm, and the analysis of the image ratios used methods described previously to calculate changes in intracellular [Ca2+]free (Taylor-Clark et al., 2008b). The ratio images were acquired every 6 s. Superfused buffer was stopped 30 s before each drug application, when 300 μl of buffer was removed from the bath and replaced by 300 μl of 2× test agent solution added between image acquisitions. After treatments, neurons were exposed to KCl (30 s, 75 mM) to confirm voltage sensitivity. At the end of experiments, both neurons and HEK cells were exposed to ionomycin (30 s, 1 μM) to obtain a maximal response.

For the analysis of Fura-2 AM-loaded cells, the measurement software converted ratiometric information to intracellular [Ca2+]free using Tsien parameters ([Ca] = Kd ((R - Rmin)/(Rmax - R)) (b)) particular to this instrumentation and the HEK cells and dissociated mouse vagal neurons. Preliminary calibration studies yielded an Rmin (352 nm/380 nm ratio under calcium-free conditions) of 0.3 for both HEK cells and mouse sensory neurons and an Rmax (352/380 ratio under calcium-saturating conditions) of 18 and 14 for HEK cells and neurons, respectively. b (380 in calcium-free conditions/380 in calcium-saturating conditions) was estimated as being 10, and the Kd was estimated as being 224 nM. In the following experimental studies, we did not specifically calibrate the relationship between ratiometric data and absolute calcium concentration for each specific cell, choosing instead to use the parameters provided from the calibration studies and relate all measurements to the peak ionomycin response in each viable cell. This effectively provided the needed cell-to-cell calibration for enumerating individual cellular responses. Only cells that had a robust response to ionomycin were included in analyses. At each time point for each cell, data were presented as the percentage change in intracellular [Ca2+]free, normalized to ionomycin: response = 100 × ([Ca2+]x - [Ca2+]bl)/([Ca2+]max - [Ca2+]bl), where [Ca2+]x was the apparent [Ca2+]free of the cell at a given time point, [Ca2+]bl was the cell's mean baseline apparent [Ca2+]free measured over 120 s, and [Ca2+]max was the cell's peak apparent [Ca2+]free during ionomycin treatment. For the neuronal experiments, neurons were defined as “responders” to a given compound if the mean response was greater than the mean baseline plus 2× the standard deviation. Only neurons that responded to KCl were included in analyses. Given that vagal and trigeminal ganglia are likely to be composed of heterogeneous neuronal populations, it is important to emphasize the point that results are presented in two distinct ways. First, the number of neurons responding (based on the criteria described above) to a given stimulus compared with the total number of neurons is reported. Second, the mean percentage change in intracellular [Ca2+]free normalized to ionomycin of those neurons that (based on the above criteria) were defined as responders is reported.

Whole-Cell Voltage Clamp. Conventional whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed at room temperature (21-24°C) using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier and pCLAMP 9 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Pipettes (3-4 MΩ) fabricated from borosilicate glass (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) were filled with an internal solution composed of 140 mM CsCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 5 mM EGTA; pH was adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. Coverslips were superfused continuously during recording with an external solution composed of 140 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM CsCl, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 mM d-Glucose (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH) and gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2. Only cells with <10 MΩ series resistances were used and compensated up to 80%. Currents were sampled at 500 Hz, and recordings were filtered at 10 kHz. The membrane potential was held at -60 mV throughout the recording. Drugs were applied to the cell and the inward current was recorded. Data were analyzed using ClampFit software (Molecular Devices) and transferred to Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) or Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) for further analysis.

C-Fiber Extracellular Recordings. Mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation followed by exsanguination. The innervated isolated trachea/bronchus preparation was prepared as described previously (Nassenstein et al., 2008). In brief, the airways and lungs with their intact extrinsic innervation (vagus nerve including vagal ganglia) were taken and placed in a dissecting dish containing Krebs bicarbonate buffer solution composed of 118 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.0 mM NaH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.9 mM CaCl2, 25.0 mM NaHCO3, and 11.1 mM dextrose and equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, pH 7.2-7.4 [also containing indomethacin (3 μM)]. Connective tissue was trimmed away leaving the trachea and lungs with their intact nerves. The airways were then pinned to the larger compartment of a custom-built two-compartment recording chamber that was lined with silicone elastomer (Sylgard; Dow Corning, Midland, MI). A vagal ganglion was gently pulled into the adjacent compartment of the chamber through a small hole and pinned. Both compartments were separately superfused with Krebs bicarbonate buffer (37°C). A sharp glass electrode was pulled by a Flaming Brown micropipette puller (P-87; Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and filled with 3 M NaCl solution. The electrode was gently inserted into the vagal ganglion so as to be placed near the cell bodies. The recorded action potentials were amplified (Microelectrode AC amplifier 1800; A-M Systems, Everett, WA), filtered (0.3 kHz of low cut-off and 1 kHz of high cut-off), and monitored on an oscilloscope (TDS340; Tektronix, Beaverton, OR) and a chart recorder (TA240; Gould, Valley View, OH). The scaled output from the amplifier was captured and analyzed by a Macintosh computer using NerveOfIt software (Phocis, Baltimore, MD). To measure conduction velocity, an electrical stimulation (S44; Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA) was applied to the center of the receptive field. The NerveOfIt software was also able to discriminate individual nerve fiber responses on the rare occasion that more than one bronchopulmonary afferent was recorded from during stimulation (electrical, mechanical, or chemical) of the lung tissue. The conduction velocity of the individual bronchopulmonary afferents was calculated by dividing the distance along the nerve pathway by the time delay between the shock artifact and the action potential evoked by electrical stimulation. Drugs were applied intratracheally as a 1-ml bolus over 10 s.

In the extracellular recording studies, the action potential discharge was quantified off-line and recorded in 1-s bins. A response was considered positive if the number of action potentials in any 1-s bin was more than twice the average background response. The background activity was usually either absent or less than 2 Hz. The peak frequency evoked by a stimulus was quantified as the maximum number of action potentials that occurred within any 1-s bin.

Chemicals. Stock solutions (200×+) of all agonists were dissolved in 100% ethanol (final concentration of 0.5% ethanol or less). 9-OA-NO2 and oleic acid were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). Fura 2AM was purchased from Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA). AP-18 was purchased from BIOMOL Research Laboratories (Plymouth Meeting, PA). HC030031 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisvile, MO). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Because of the reported instability of 9-OA-NO2 in aqueous solutions [half-lifeaq of approximately 2 h (Gorczynski et al., 2007)], 9-OA-NO2 was dissolved into the appropriate buffer within 5 min of experimental use.

Results

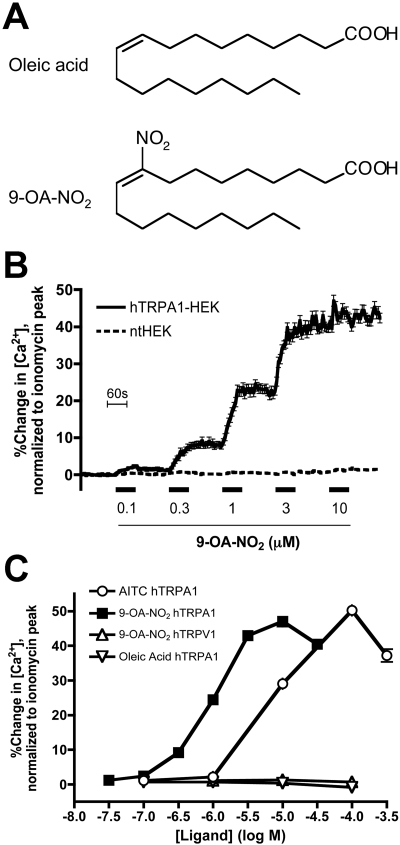

9-OA-NO2 Activates TRPA1 Expressed on HEK293 Cells. We have shown previously that HEK293 cells stably transfected with human TRPA1 (hTRPA1-HEK) responded, in calcium imaging assays, to the reactive electrophilic products of oxidative stress, such as 4HNE and 8-iso prostaglandin A2 (Taylor-Clark et al., 2008a,b). Using the same hTRPA1-HEK cells, we found that 9-OA-NO2 (30 nM-30 μM; for structure, see Fig. 1A) activated TRPA1 channels (maximal response of 47 ± 1.5% of ionomycin, n = 156) with an approximate EC50 of 1 μM (Fig. 1, B and C). The potency of 9-OA-NO2 at TRPA1 channels is 10-fold greater than the canonical selective TRPA1 agonist AITC, which activated the hTRPA1-HEK cells (maximal response of 50 ± 1.3% of ionomycin, n = 269) with an approximate EC50 of 10 μM (Fig. 1C). 9-OA-NO2 (100 nM-100 μM) failed to activate ntHEK cells (maximal response of 3.2 ± 0.13% of ionomycin, n = 369; Fig. 1B), suggesting that the increase in cytosolic calcium in the HEK cells caused by 9-OA-NO2 required TRPA1 channels. We investigated the effect of oleic acid on TRPA1 channels. Oleic acid (100 nM-100 μM) failed to activate hTRPA1-HEK cells (maximal response of 0.73 ± 0.12% of ionomycin, n = 168; Fig. 1C), suggesting that the addition of the NO2 group onto the fatty acid was crucial to TRPA1 channel activation.

Fig. 1.

Activation of hTRPA1-HEK cells by the nitrated fatty acid 9-OA-NO2. A, structural formulae of oleic acid and 9-OA-NO2. B, mean ± S.E.M. Ca2+ responses of hTRPA1-HEK cells to putative endogenous TRPA1 agonist 9-OA-NO2 (0.1-10 μM). All drugs were applied for 60 s (blocked line). Black line, responses of hTRPA1-HEK cells (n = 156); broken line, responses of nt-HEK cells (n = 369). C, dose-response relationships of Ca2+ responses of hTRPA1-HEK cells for 9-OA-NO2, AITC, and oleic acid, and responses of hTRPV1-HEK cells for 9-OA-NO2 (0.03-300 μM; data comprise >156 cells). Data represent the maximal response during the 60-s agonist treatment taken from mean cell response versus time curves (note that the S.E.M. is contained within symbol).

We have previously demonstrated that the highly reactive electrophile 4-oxononenal (4ONE), which activates hTRPA1-HEK cells with an approximate EC50 of 2 μM, is also an agonist for TRPV1 channel, although only at 100 μM (Taylor-Clark et al., 2008a). We investigated whether or not 9-OA-NO2 was also capable of activating TRPV1 channels. Using calcium imaging of hTRPV1-HEK cells, we found that 9-OA-NO2 (100 nM-100 μM) failed to activate TRPV1 channels (n = 168, Fig. 1C). As expected, the hTRPV1-HEK cells responded robustly to the canonical TRPV1 agonist capsaicin (300 nM, maximal response of 34 ± 1.1% of ionomycin, n = 168, data not shown).

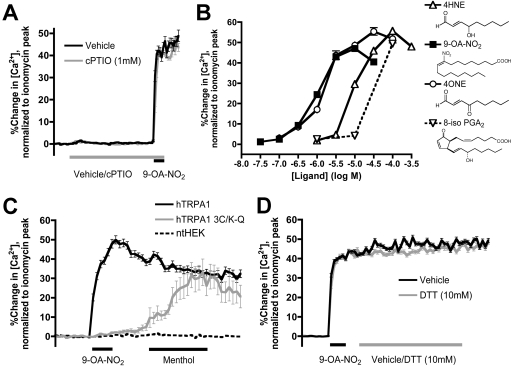

We next investigated the mechanism by which 9-OA-NO2 activates TRPA1 channels. It has been reported that nitrated fatty acids may mediate some of their biological actions via the release of nitric oxide (NO) (Schopfer et al., 2005). It is conceivable that NO then directly nitrosylates the channel causing activation, as has been shown for other TRP channels (Yoshida et al., 2006). Indeed, NO donors have been shown to have a weak agonist effect on TRPA1 channels (Sawada et al., 2008; Takahashi et al., 2008). We confirmed the weak agonist effect on TRPA1 activity of two different NO donors, sodium nitroprusside (300 μM) and SIN-1 (300 μM), which caused an increase in calcium in hTRPA1-HEK cells (n = 75) of 8.7 ± 0.56% and 5.0 ± 0.31% of ionomycin, respectively (data not shown). We then investigated the contribution of NO to 9-OA-NO2--induced TRPA1 activation using the NO scavenger carboxy-PTIO. Incubating hTRPA1-HEK cells with 1 mM carboxy-PTIO for 10 min had no effect on the activation of TRPA1 by 9-OA-NO2 (3 μM): maximal response of 49 ± 2.3% of ionomycin (n = 80) and 46 ± 1.7% of ionomycin (n = 212) for vehicle and carboxy-PTIO treatments, respectively (Fig. 2A). Overall the data suggests that NO is unlikely to play a major role in the activation of TRPA1 channels by 9-OA-NO2.

Fig. 2.

9-OA-NO2 activates TRPA1 via covalent modification. A, mean ± S.E.M. Ca2+ responses of hTRPA1-HEK cells to 9-OA-NO2 (3 μM, 60 s), with (gray line, n = 212) and without (black line, n = 80) pretreatment with NO scavenger carboxy-PTIO (1 mM). B, Dose-response relationships of Ca2+ responses of hTRPA1-HEK cells for 9-OA-NO2, 4HNE, 4ONE, and 8-iso PGA2 (data comprise >156 cells; some data taken from Taylor-Clark et al., 2008a,b). Data represent the maximal response during the 60-s agonist treatment taken from mean cell response versus time curves (note that the S.E.M. is contained within symbol). C, mean ± S.E.M. Ca2+ responses to 9-OA-NO2 (3 μM, 60 s) and menthol (300 μM, 180 s) of ntHEK cells (broken line, n = 88), HEK cells transiently tranfected with hTRPA1 (black line, n = 166) and HEK cells transiently transfected with hTRPA1-3C/K-Q (gray line, n = 18). D, effect of DTT (10 mM, gray line, n = 259) and vehicle (black line, n = 204) on the mean ± S.E.M. Ca2+ responses of hTRPA1-HEK cells to 9-OA-NO2 (3 μM, 60 s).

Given that 9-OA-NO2 activates TRPA1 channels in an NO-independent manner and that oleic acid has no effect on the channel, it is likely that the electrophilic C=C-NO2 moiety is responsible for the TRPA1 channel activation. This would be consistent with previous reports that direct covalent modification of TRPA1 channel cysteines induces activation (Hinman et al., 2006; Macpherson et al., 2007a). 9-OA-NO2 is a reactive electrophilic molecule that has been shown to readily adduct amino acid residues such as cysteines (Michael reaction) (Baker et al., 2007). Indeed, when the TRPA1 activation potency of 9-OA-NO2 is compared with other endogenous TRPA1 “covalently modifying” agonists investigated in our heterologous system (Fig. 2B, and see Taylor-Clark et al., 2008a,b), the rank order of -LogEC50 [9-OA-NO2 (6) ≥ 4ONE (5.8) > 4HNE (5) >8-iso PGA2 (4.5)] is almost identical to the rank order of second-order rate constants for the reaction of glutathione's cysteine residue in model systems [9-OA-NO2 (183 M-1 · s-1) > 4ONE (145 M-1 · s-1) > 4HNE (1.3 M-1 · s-1) > 8-iso PGA2 (0.7 M-1 · s-1)] (Baker et al., 2007). This suggests that modification of cysteines may play a role in the activation of TRPA1 by 9-OA-NO2. For human TRPA1 channels, covalent modification (Michael reaction)-induced TRPA1 activation is dependent on the presence of three crucial cysteine residues (Cys619, Cys639, and Cys663) and one lysine residue (Lys708) on the channel's intracellular N terminus (Hinman et al., 2006). We hypothesized that 9-OA-NO2 would fail to activate TRPA1 channels with mutations at these four residues. Using plasmid cDNA encoding the mutant hTRPA1-3C/K-Q and wild-type hTRPA1 channels (see Materials and Methods), we found that, as expected, 9-OA-NO2 (3 μM) activated wild-type hTRPA1 channels (maximal response of 50 ± 2.1% of ionomycin, n = 166) but failed to activate the mutant channel (maximal response of 3.0 ± 1.0% of ionomycin, n = 18), whereas menthol (300 μM), which activates TRPA1 channels independently of Cys619, Cys639, and Cys663 (Xiao et al., 2008), did activate the mutant (maximal response of 33 ± 7.0% of ionomycin; Fig. 2C). Neither 9-OA-NO2 nor menthol activated ntHEK cells [maximal responses of 0.45 ± 0.12% and 1.7 ± 0.16% of ionomycin (n = 88), respectively]. The data clearly suggest that 9-OA-NO2 activates TRPA1 via covalent modification.

It is noteworthy that, unlike products of oxidative stress such as 4ONE and 4HNE, 9-OA-NO2 has been shown to form Michael adducts with cysteine residues in a manner that can be reversed by the thiol-containing reducing agents dithiothreitol (DTT) and GSH (Batthyany et al., 2006). Thiol-reducing agents are present in vivo in both extracellular and intracellular compartments, and their levels are sensitive to the redox state of the environment (Szabó et al., 2007; Valko et al., 2007). DTT (1-5 mM) has previously been shown to reverse the activation of TRPA1 channels by H2O2 but not by 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 or 4HNE (Andersson et al., 2008; Takahashi et al., 2008). In calcium imaging assays of hTRPA1-HEK cells, we found that 7-min treatment with 10 mM DTT failed to reverse the activation of TRPA1 by 9-OA-NO2 (3 μM): maximal response of 51 ± 1.1% (n = 204) and 49 ± 1.2% (n = 259) of ionomycin for vehicle and DTT treatments, respectively (Fig. 2D). We found a similar lack of reversibility when using 250 μM GSH ethyl ester (membrane-permeant form of GSH) (data not shown).

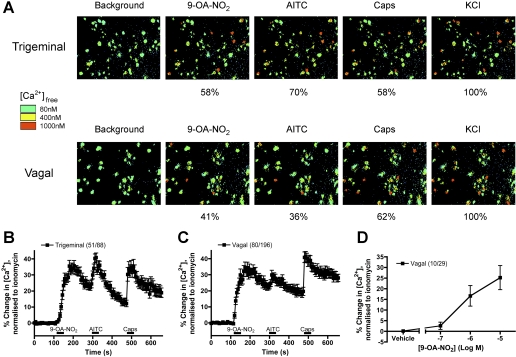

9-OA-NO2 Activates TRPA1-Expressing Nociceptive Sensory Neurons. We and others have previously identified TRPA1 channel responses in subpopulations of native somatosensory and visceral sensory neurons from trigeminal, vagal and dorsal root ganglia (Bandell et al., 2004; Jordt et al., 2004; Nassenstein et al., 2008). These TRPA1-expressing neurons almost always also respond to capsaicin, the TRPV1 agonist. Here we used calcium imaging to address the hypothesis that 9-OA-NO2 would activate sensory neurons that also respond to AITC, the canonical TRPA1 channel agonist, and to capsaicin. 9-OA-NO2 (10 μM) activated approximately 60% of trigeminal dissociated sensory neurons and 40% of vagal dissociated neurons (Fig. 3A). AITC (100 μM) and capsaicin (1 μM) activated similar proportions of the dissociated neurons, although there seemed to be a greater percentage of capsaicin-sensitive neurons in the vagal ganglia compared with the trigeminal ganglia. When only those neurons that responded to 9-OA-NO2 were combined, the mean responses demonstrated that 9-OA-NO2 (10 μM) caused a robust activation of sensory neurons (maximal response of 35 ± 3.4% and 36 ± 3.3% of ionomycin for vagal and trigeminal neurons, respectively) that also responded strongly to AITC and capsaicin (Fig. 3, B and C), suggesting that the actions of 9-OA-NO2 actions were restricted to nociceptive neurons that were activated by TRPA1 and TRPV1 agonists. Next, we assessed the potency of 9-OA-NO2-elicited responses in vagal sensory neurons. As with the hTRPA1-HEK cells, 0.1 μM 9-OA-NO2 evoked only minor responses, which increased dramatically at 1 μM and at 10 μM began to approach a maximum, suggesting a similar order of magnitude between the 9-OA-NO2 responses at heterologously expressed TRPA1 channels and native sensory neurons (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

9-OA-NO2 activates a subset of trigeminal and vagal neurons. A, representative Fura 2AM ratiometric image of Ca2+ responses of trigeminal (top) and vagal (bottom) neurons to 9-OA-NO2 (10 μM), AITC (100 μM), capsaicin (Caps, 1 μM), and KCl (75 mM). Percentage of KCl-sensitive neurons responding to the agonists is illustrated below each image. B and C, mean ± S.E.M. Ca2+ responses of trigeminal (B) and vagal (C) neurons responding to 9-OA-NO2 (10 μM). Response to AITC (100 μM) and capsaicin (Caps, 1 μM) also shown. Blocked line denotes the 30-s application of agonist. D, dose-response relationship of Ca2+ responses of vagal neurons to 9-OA-NO2 (0.1 to 10 μM). Data represent the maximal response during the 30-s agonist treatment taken from mean cell response versus time curves. All neurons responded to KCl (75 mM) applied immediately before ionomycin.

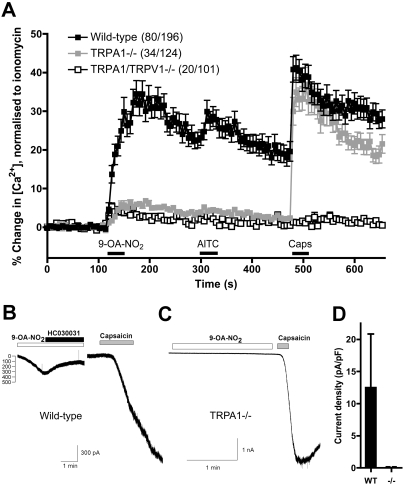

TRPA1(-/-) Neurons Are Insensitive to 9-OA-NO2. To confirm the molecular identity of the 9-OA-NO2-activated channels in native nociceptors, we compared responses of wild-type vagal neurons with those of vagal neurons derived from TRPA1(-/-) mice. In calcium imaging assays, 80 of 195 wild-type vagal neurons responded to 9-OA-NO2 (10 μM) with a maximal response of 35 ± 3.4% of ionomycin. However, only 34 of 124 TRPA1(-/-) neurons responded to 9-OA-NO2, with a dramatically reduced maximal response of 6.8 ± 0.6% of ionomycin, indicating that TRPA1 channels were responsible for the great majority of the 9-OA-NO2 response (Fig. 4A). As expected, the TRPA1(-/-) neurons also failed to respond to AITC (100 μM) but responded robustly to capsaicin (1 μM). Although 9-OA-NO2 had no observable effect on our hTRPV1-HEK cells, it was possible that the minor residual 9-OA-NO2-induced response in TRPA1(-/-) neurons was due to electrophile-dependent TRPV1 activation (Salazar et al., 2008; Taylor-Clark et al., 2008a). We addressed this hypothesis using mice with genetic deletion of both TRPA1 and TRPV1 channels. Consistent with our hTRPV1-HEK cell data, the neuronal responses of TRPA1(-/-)/TRPV1(-/-) mice were indistinguishable from TRPA1(-/-) mice, with 9-OA-NO2 (10 μM) activating 20 of 101 neurons with a maximal response of 5.3 ± 0.9% of ionomycin (Fig. 4A). As expected, TRPA1(-/-)/TRPV1(-/-) neurons also failed to respond to both AITC and capsaicin.

Fig. 4.

9-OA-NO2 fails to activate TRPA1(-/-) vagal neurons. A, mean ± S.E.M. Ca2+ responses of vagal neurons responding to 9-OA-NO2 (10 μM). Response to AITC (100 μM) and capsaicin (Caps, 1 μM) also shown. Data comprise neurons from wild-type mice (black squares, 80 of 196 neurons responding), neurons from TRPA1(-/-) mice (gray squares, 34 of 124), and neurons from TRPA1(-/-)/TRPV1(-/-) mice (white squares, 20 of 101). Blocked line denotes the 30-s application of agonist. All neurons responded to KCl (75 mM) applied immediately before ionomycin. B, representative trace of the inward current evoked in a wild-type vagal neuron (held at -60mV) by 9-OA-NO2 [10 μM; and reversed by HC030031 (20 μM)] and capsaicin (1 μM). C, representative trace of the inward current evoked in a TRPA1(-/-) vagal neuron (held at -60 mV) by 9-OA-NO2 (10 μM) and capsaicin (1 μM). D, mean ± S.E.M. Inward current density (pA/pF) of vagal neurons responding to 9-OA-NO2 (10 μM). Data comprise neurons from wild-type mice (black column) and neurons from TRPA1(-/-) mice (white column).

We further investigated the responses of native neurons to 9-OA-NO2 in whole-cell voltage clamp of vagal neurons. In the nominal absence of Ca2+, 9-OA-NO2 (10 μM) induced an inward current in 7 of 10 wild-type neurons (mean current density 12.5 ± 8.3 pA/pF), which was reversed by HC030031 (20 μM) (Fig. 4, B and D), the selective TRPA1 antagonist with an IC50 of approximately 1 μM (McNamara et al., 2007). However, 9-OA-NO2 (10 μM) had virtually no effect on TRPA1(-/-) neurons, with only 1 of 9 responding (current density 0.19 pA/pF) (Fig. 4, C and D). As expected, capsaicin (1 μM) responses were no different in neurons from wild-type and those from TRPA1(-/-) mice: four of eight responded with mean current density of 170 ± 52 pA/pF and seven of nine responded with mean current density of 158 ± 59 pA/pF, respectively. Taking the calcium imaging and voltage clamp data together, we conclude that the activation of native neurons by 9-OA-NO2 is overwhelmingly dependent on TRPA1 channels.

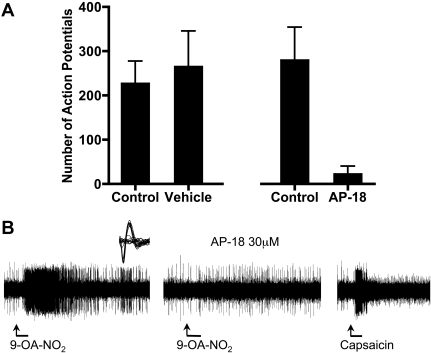

9-OA-NO2 Induces Action Potential Discharge from Visceral C Fibers via TRPA1. The effect of 9-OA-NO2 on nociceptive nerve endings was analyzed using extracellular recording techniques in an ex vivo vagal innervated mouse lung preparation (Kollarik et al., 2003). Nociceptive vagal C fibers were considered those nerve fibers that responded with action potential discharge to capsaicin and α,β-methylene ATP. We have previously shown that TRPA1 agonists activate only this bronchopulmonary nerve population (Nassenstein et al., 2008; Taylor-Clark et al., 2008b). In seven experiments, the C fiber under study (conduction velocities ranged from 0.4 to 0.7 m/s) responded strongly with action potential discharge to capsaicin (0.3 μM) and α,β-methylene ATP (10 μM). In seven of seven of these capsaicin sensitive nerve fibers, 9-OA-NO2 (30 μM) evoked action potential discharge (Fig. 5, A and 5). The action potential discharge in response to a 1-ml infusion of 9-OA-NO2 delivered over 20 s had an onset within the 20-s delivery period, and generally persisted for only approximately 2 to 3 min. The total number of action potentials averaged 227 ± 51 (Fig. 5A). The peak frequency of discharge induced by 9-OA-NO2 averaged 12 ± 2Hz, which was approximately 50% of that observed with capsaicin (24 ± 4Hz, added at the end of the experiment). The response to 9-OA-NO2 was reproducible within a given nerve fiber. Treating the tissue a second time 20 min after the cessation of action potential discharge resulted in a response not significantly different from the first response (Fig. 5A). AP-18 (30 μM), the selective TRPA1 antagonist with an IC50 of approximately 3 μM (Petrus et al., 2007) nearly abolished the 9-OA-NO2-induced action potential discharge in the lung C fibers in five of five fibers tested (Fig. 5, A and B). We have noted previously that there is a subpopulation of α,β methylene ATP-sensitive fibers in the mouse lung that are insensitive to capsaicin (Kollarik et al., 2003). We evaluated two of these capsaicin-insensitive fibers, and both were found also to be insensitive to 9-OA-NO2.

Fig. 5.

9-OA-NO2 activation of C-fiber terminals. A, mean ± S.E.M. Total action potential discharge from individual identified bronchopulmonary C fibers to 9-OA-NO2 (30 μM) in paired experiments: control and vehicle-treated fibers (n = 7) and control and 30 μM AP-18-treated fibers (n = 5). All C fibers responded to capsaicin (300 μM) at the end of the experiment. Only one fiber was assessed in each preparation. B, representative trace of action potential discharge from a single bronchopulmonary C fiber evoked by 9-OA-NO2 (30 μM) in the absence and presence of AP-18 (30 μM), followed by the response to capsaicin (300 nM). Inset, action potential wave form of the individual bronchopulmonary C fiber.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that the nitrated fatty acid 9-OA-NO2 is a stimulator of somatosensory and visceral nociceptors via the selective and direct activation of TRPA1 channels. Based on our concentration-response analysis in both neurons and hTRPA1-HEK cells, we can conclude that this compound is the most potent endogenous TRPA1 agonist thus far described.

9-OA-NO2 activated hTRPA1 channels in a heterologous system at concentrations just above those levels found in plasma samples from healthy humans (Baker et al., 2005) and well within the range of concentrations that OA-NO2 induces other (non-neuronal) biological effects (Freeman et al., 2008; Trostchansky and Rubbo, 2008). The parent compound of 9-OA-NO2, oleic acid, had no effect on hTRPA1, suggesting that the addition of the highly electrophilic nitro group was responsible for the actions of 9-OA-NO2 on TRPA1, rather than the hydrocarbon chain or the carboxylic acid group. Nitrated fatty acids have been shown to be stable in lipophilic environments, but they have been shown to release NO in aqueous solutions (Freeman et al., 2008). However, compared with other nitrated fatty acids, OA-NO2 is relatively stable (half-lifeaq of approximately 2 h) (Gorczynski et al., 2007), and so it was not surprising that the NO scavenger carboxy-PTIO had no effect on 9-OA-NO2 TRPA1 activation. The capacity of NO itself to activate TRPA1 is not yet clear. Although we confirmed, using SIN-1 and sodium nitroprusside, the mild activation of TRPA1 channels by the NO donors demonstrated by other groups (Sawada et al., 2008; Takahashi et al., 2008), these studies are confounded by reports that NO donors, including sodium nitroprusside and SNAP, that are typically thought to have no oxidative effect, also produce superoxide (Pieper et al., 1994). Superoxide (and its downstream ROS H2O2) can independently induce TRPA1 activation (Sawada et al., 2008). Further studies are needed to confirm a direct interaction of NO with the TRPA1 channel. Nevertheless, based on the potency and efficacy of 9-OA-NO2's activation of TRPA1, it is likely that, regardless of any direct (minor) effect of NO on the channel, the primary mechanism of nitrative stress-induced nociceptors activation is via the nitration of fatty acids.

Using a mutated TRPA1 channel that has mutations at Cys619, Cys639, Cys663, and Lys708, which renders it insensitive to electrophilic activation (Hinman et al., 2006), we were able to show that 9-OA-NO2 activated the channel through interactions with these nucleophilic residues. This was unsurprising given the evidence that the activation was NO-independent and the activation potency ratio of 9-OA-NO2 and other endogenous electrophiles was similar to their described Michael adduction to cysteines (Baker et al., 2007).

Using the reducing agent DTT (and GSH), we found that the activation of hTRPA1 channels by 9-OA-NO2 was not reversible by these agents. DTT has previously been shown to reverse TRPA1 activation by H2O2 but not by the reactive unsaturated aldehyde 4HNE (Andersson et al., 2008; Sawada et al., 2008), which activates TRPA1 via Michael adduction of Cys619, Cys639, Cys663, and Lys708 (Trevisani et al., 2007). Our finding of a nonreversible Michael adduction by 9-OA-NO2 was unexpected, because OA-NO2 and nitrolinoleic acid have both been shown to form reversible Michael adducts with cysteine residues on GSH and other peptides/proteins (Batthyany et al., 2006), although OA-NO2 does irreversibly react with xanthine oxidoreductase (Kelley et al., 2008). It would be prudent not to overextend any conclusions based on these in vitro heterologous system studies, but there remains the possibility that for OA-NO2, there is a mismatch between its adduction of cysteines on TRPA1 (pro-nociception) and its adduction of cysteines on antioxidants (anti-nociception), which would augment the efficacy of neuronal activation in vivo.

TRPA1 channels are preferentially expressed on small-diameter nociceptive sensory neurons in trigeminal, vagal, and dorsal root ganglia (Bandell et al., 2004; Jordt et al., 2004; Nassenstein et al., 2008). In our experiments, we found that 9-OA-NO2 activated a population of small-diameter neurons that also responded to AITC, another TRPA1 agonist, and capsaicin, the TRPV1 agonist. Similar results were seen for both trigeminal and vagal neurons, suggesting that somatosensory and visceral nociceptors are activated by the nitrated fatty acid. Using TRPA1(-/-) vagal neurons, we confirmed in calcium imaging and voltage-clamp studies the molecular identity of the target of 9-OA-NO2 in sensory neurons as being TRPA1, which is consistent with TRPA1 being the sole target of acrolein and 4HNE (products of lipid peroxidation) (Bautista et al., 2006; Macpherson et al., 2007b; Trevisani et al., 2007). Previous studies had shown that the lipid peroxidation product with the greatest electrophilicity, 4ONE (Doorn and Petersen, 2002; Baker et al., 2007), was able not only to activate TRPA1 channels but also to gate TRPV1 channels (Taylor-Clark et al., 2008a). Given that 9-OA-NO2 is more electrophilic than 4ONE, as determined by cysteine adduction (Baker et al., 2007), we would have predicted that 9-OA-NO2 would have activated hTRPV1-HEK cells. In addition, another oleic acid derivative, N-oleoylethanolamine, has been shown to gate TRPV1 channels (Movahed et al., 2005). However, 9-OA-NO2 failed to activate TRPV1 channels, and there was no difference between the response to 9-OA-NO2 in vagal neurons from TRPA1(-/-) mice and TRPA1(-/-)/TRPV1(-/-) mice. This lack of effect suggests that TRPV1 activation by reactive molecules is not solely dependent on the degree of electrophilicity.

The importance of the actions of 9-OA-NO2 on TRPA1 channels was confirmed at the level of the sensory nerve terminals in ex vivo extracellular bronchopulmonary C-fiber recordings. We have previously shown that mouse vagal afferent capsaicin-sensitive C fibers innervating the lungs can be activated by TRPA1 agonists and that these responses are abolished by TRPA1 antagonists and by genetic deletion of TRPA1 channels (Nassenstein et al., 2008; Taylor-Clark et al., 2008a). As predicted from the in vitro studies, 9-OA-NO2 induced robust action potential discharge from bronchopulmonary capsaicin-sensitive C-fiber terminals in a manner that was inhibited by the selective TRPA1 antagonist AP-18. This result is consistent with previous reports that lipid peroxidation products and AITC and other isothiocyanates evoke pain, local reflexes and central reflexes through the activation of TRPA1 channels on nociceptive sensory nerves (Trevisani et al., 2007; Andersson et al., 2008; Taylor-Clark et al., 2008a,b; Bessac et al., 2009).

Many of NO's pathophysiological and cytotoxic effects are thought to be mediated by the NO-derived RNS (Radi, 2004), which have been shown to contribute in vivo to inflammatory models (Salvemini et al., 2006) and to multiple disease states including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, viral-induced pneumonia, cystic fibrosis, ischemic-reperfusion injury, circulatory shock, arthritis, colitis, and pain (Radi, 2004; Ricciardolo et al., 2006; Szabó et al., 2007). In addition, there are exogenous stimuli that could contribute to the formation of RNS, for example nitrogen oxides (NOx) in polluted air and cigarette smoke. The contribution of nitrated fatty acids, including OA-NO2, to the activation of nociceptive sensory nerves in these conditions is as yet unknown. High nanomolar levels of nitrated fatty acids have been detected in plasma and cell membranes (Baker et al., 2005), and evidence suggests that these levels increase during inflammation (Balazy and Poff, 2004). In addition, much of the detected nitrated fatty acid is esterified (Baker et al., 2005), which suggests that subsequent activation of phospholipase A2 may release more nitrated fatty acids long after conditions of nitrative stress have diminished (Jain et al., 2008). Finally, it is likely that nociceptive nerves are themselves capable of producing RNS (and presumably nitrated fatty acids) as they express proteins capable of synthesizing superoxide [NADPH oxidase (Dvorakova et al., 1999)] and NO [nNOS (Mazzone and McGovern, 2008)]. Taken together, our findings that OA-NO2 is a potent endogenous activator of TRPA1 suggests a novel relevant mechanism by which excessive NO production and nitrative stress can contribute to nociception in inflammation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr David Julius (University of California San Francisco) for the hTRPA1-3C/K-Q mutant cDNA. We also thank Dr. Donald MacGlashan, Jr., and Sonya Meeker for technical assistance, and Dr. M. Allen McAlexander for insightful discussion regarding this manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grant K99-HL088520]; GlaxoSmithKline; and the Blaustein Pain Research Fund.

ABBREVIATIONS: NOS, nitric-oxide synthase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; OA, oleic acid; OA-NO2, nitrooleic acid; 4HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; TRP, transient receptor potential; AITC, allyl isothiocyanate; HEK, human embryonic kidney; FBS, fetal bovine serum; AM, acetyoxymethyl ester; HC030031, 2-(1,3-dimethyl-2,6-dioxo-1,2,3,6-tetrahydro-7H-purin-7-yl)-N-(4-isopropylphenyl)acetamide; 4ONE, 4-oxononenal; PTIO, 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide; DTT, dithiothreitol; PGA2, prostaglandin A2; carboxyPTIO, 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide; SIN-1, 3-morpholino-sydnonimine; AP-18, 4-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-methylbut-3-en-2-oxime; hTRPA1-HEK, HEK cells stably transfected with human TRPA1 channels; hTRPV1-HEK, HEK cells stably transfected with human TRPV1 channels.

References

- Andersson DA, Gentry C, Moss S, and Bevan S (2008) Transient receptor potential A1 is a sensory receptor for multiple products of oxidative stress. J Neurosci 28 2485-2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LM, Baker PR, Golin-Bisello F, Schopfer FJ, Fink M, Woodcock SR, Branchaud BP, Radi R, and Freeman BA (2007) Nitro-fatty acid reaction with glutathione and cysteine. Kinetic analysis of thiol alkylation by a Michael addition reaction. J Biol Chem 282 31085-31093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PR, Lin Y, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Groeger AL, Batthyany C, Sweeney S, Long MH, Iles KE, Baker LM, et al. (2005) Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: multiple nitrated unsaturated fatty acid derivatives exist in human blood and urine and serve as endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. J Biol Chem 280 42464-42475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazy M and Poff CD (2004) Biological nitration of arachidonic acid. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2 81-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandell M, Story GM, Hwang SW, Viswanath V, Eid SR, Petrus MJ, Earley TJ, and Patapoutian A (2004) Noxious cold ion channel TRPA1 is activated by pungent compounds and bradykinin. Neuron 41 849-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batthyany C, Schopfer FJ, Baker PR, Durán R, Baker LM, Huang Y, Cerveñansky C, Branchaud BP, and Freeman BA (2006) Reversible post-translational modification of proteins by nitrated fatty acids in vivo. J Biol Chem 281 20450-20463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista DM, Jordt SE, Nikai T, Tsuruda PR, Read AJ, Poblete J, Yamoah EN, Basbaum AI, and Julius D (2006) TRPA1 mediates the inflammatory actions of environmental irritants and proalgesic agents. Cell 124 1269-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessac BF, Sivula M, von Hehn CA, Caceres AI, Escalera J and Jordt SE (2009) Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 antagonists block the noxious effects of toxic industrial isocyanates and tear gases. FASEB J doi: 10.1096/fj.08-117812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bian K and Murad F (2003) Nitric oxide (NO)—biogeneration, regulation, and relevance to human diseases. Front Biosci 8 d264-d278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JB, Gray J, Gunthorpe MJ, Hatcher JP, Davey PT, Overend P, Harries MH, Latcham J, Clapham C, Atkinson K, et al. (2000) Vanilloid receptor-1 is essential for inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia. Nature 405 183-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Petrocellis L, Vellani V, Schiano-Moriello A, Marini P, Magherini PC, Orlando P, and Di Marzo V (2008) Plant-derived cannabinoids modulate the activity of transient receptor potential channels of ankyrin type-1 and melastatin type-8. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 325 1007-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorn JA and Petersen DR (2002) Covalent modification of amino acid nucleophiles by the lipid peroxidation products 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and 4-oxo-2-nonenal. Chem Res Toxicol 15 1445-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorakova M, Höhler B, Richter E, Burritt JB, and Kummer W (1999) Rat sensory neurons contain cytochrome b558 large subunit immunoreactivity. Neuroreport 10 2615-2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman BA, Baker PR, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Napolitano A, and d'Ischia M (2008) Nitro-fatty acid formation and signaling. J Biol Chem 283 15515-15519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner HW (1989) Oxygen radical chemistry of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Free Radic Biol Med 7 65-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczynski MJ, Huang J, Lee H, and King SB (2007) Evaluation of nitroalkenes as nitric oxide donors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 17 2013-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinman A, Chuang HH, Bautista DM, and Julius D (2006) TRP channel activation by reversible covalent modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 19564-19568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain K, Siddam A, Marathi A, Roy U, Falck JR, and Balazy M (2008) The mechanism of oleic acid nitration by *NO(2). Free Radic Biol Med 45 269-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordt SE, Bautista DM, Chuang HH, McKemy DD, Zygmunt PM, Högestätt ED, Meng ID, and Julius D (2004) Mustard oils and cannabinoids excite sensory nerve fibres through the TRP channel ANKTM1. Nature 427 260-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley EE, Batthyany CI, Hundley NJ, Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Del Rio JM, Schopfer FJ, Lancaster JR Jr, Freeman BA, and Tarpey MM (2008) Nitro-oleic acid: a novel and irreversible inhibitor of xanthine oxidoreductase. J Biol Chem 283 36176-36184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollarik M, Dinh QT, Fischer A, and Undem BJ (2003) Capsaicin-sensitive and -insensitive vagal bronchopulmonary C-fibres in the mouse. J Physiol 551 869-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson LJ, Dubin AE, Evans MJ, Marr F, Schultz PG, Cravatt BF, and Patapoutian A (2007a) Noxious compounds activate TRPA1 ion channels through covalent modification of cysteines. Nature 445 541-545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson LJ, Xiao B, Kwan KY, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, Hwang S, Cravatt B, Corey DP, and Patapoutian A (2007b) An ion channel essential for sensing chemical damage. J Neurosci 27 11412-11415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone SB and McGovern AE (2008) Immunohistochemical characterization of nodose cough receptor neurons projecting to the trachea of guinea pigs. Cough 4 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara CR, Mandel-Brehm J, Bautista DM, Siemens J, Deranian KL, Zhao M, Hayward NJ, Chong JA, Julius D, Moran MM, et al. (2007) TRPA1 mediates formalin-induced pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 13525-13530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller MN, Li Q, Vitturi DA, Robinson JM, Lancaster JR Jr, and Denicola A (2007) Membrane “lens” effect: focusing the formation of reactive nitrogen oxides from the *NO/O2 reaction. Chem Res Toxicol 20 709-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movahed P, Jönsson BA, Birnir B, Wingstrand JA, Jørgensen TD, Ermund A, Sterner O, Zygmunt PM, and Högestätt ED (2005) Endogenous unsaturated C18 N-acylethanolamines are vanilloid receptor (TRPV1) agonists. J Biol Chem 280 38496-38504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassenstein C, Kwong K, Taylor-Clark T, Kollarik M, Macglashan DM, Braun A, and Undem BJ (2008) Expression and function of the ion channel TRPA1 in vagal afferent nerves innervating mouse lungs. J Physiol 586 1595-1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell VB, Eiserich JP, Chumley PH, Jablonsky MJ, Krishna NR, Kirk M, Barnes S, Darley-Usmar VM, and Freeman BA (1999) Nitration of unsaturated fatty acids by nitric oxide-derived reactive nitrogen species peroxynitrite, nitrous acid, nitrogen dioxide, and nitronium ion. Chem Res Toxicol 12 83-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrus M, Peier AM, Bandell M, Hwang SW, Huynh T, Olney N, Jegla T, and Patapoutian A (2007) A role of TRPA1 in mechanical hyperalgesia is revealed by pharmacological inhibition. Mol Pain 3 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper GM, Clarke GA, and Gross GJ (1994) Stimulatory and inhibitory action of nitric oxide donor agents vs. nitrovasodilators on reactive oxygen production by isolated polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 269 451-456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radi R (2004) Nitric oxide, oxidants, and protein tyrosine nitration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 4003-4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardolo FL, Di Stefano A, Sabatini F, and Folkerts G (2006) Reactive nitrogen species in the respiratory tract. Eur J Pharmacol 533 240-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar H, Llorente I, Jara-Oseguera A, Garcia-Villegas R, Munari M, Gordon SE, Islas LD and Rosenbaum T (2008) A single N-terminal cysteine in TRPV1 determines activation by pungent compounds from onion and garlic. Nat Neurosci 11 255-261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvemini D, Doyle TM, and Cuzzocrea S (2006) Superoxide, peroxynitrite and oxidative/nitrative stress in inflammation. Biochem Soc Trans 34 965-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada Y, Hosokawa H, Matsumura K, and Kobayashi S (2008) Activation of transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 by hydrogen peroxide. Eur J Neurosci 27 1131-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer FJ, Baker PR, Giles G, Chumley P, Batthyany C, Crawford J, Patel RP, Hogg N, Branchaud BP, Lancaster JR Jr, et al. (2005) Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling. Nitrolinoleic acid is a hydrophobically stabilized nitric oxide donor. J Biol Chem 280 19289-19297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó C, Ischiropoulos H, and Radi R (2007) Peroxynitrite: biochemistry, pathophysiology and development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6 662-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Mizuno Y, Kozai D, Yamamoto S, Kiyonaka S, Shibata T, Uchida K, and Mori Y (2008) Molecular characterization of TRPA1 channel activation by cysteine-reactive inflammatory mediators. Channels (Austin) 2 287-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Clark TE, Kiros F, Carr MJ and McAlexander MA (2009) Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 mediates toluene diisocyanate-evoked respiratory irritation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0292OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Taylor-Clark TE, McAlexander MA, Nassenstein C, Sheardown SA, Wilson S, Thornton J, Carr MJ, and Undem BJ (2008a) Relative contributions of TRPA1 and TRPV1 channels in the activation of vagal bronchopulmonary C-fibres by the endogenous autacoid 4-oxononenal. J Physiol 586 3447-3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Clark TE, Undem BJ, Macglashan DW Jr, Ghatta S, Carr MJ, and McAlexander MA (2008b) Prostaglandin-induced activation of nociceptive neurons via direct interaction with transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1). Mol Pharmacol 73 274-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevisani M, Siemens J, Materazzi S, Bautista DM, Nassini R, Campi B, Imamachi N, Andrè E, Patacchini R, Cottrell GS, et al. (2007) 4-Hydroxynonenal, an endogenous aldehyde, causes pain and neurogenic inflammation through activation of the irritant receptor TRPA1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 13519-13524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trostchansky A and Rubbo H (2008) Nitrated fatty acids: mechanisms of formation, chemical characterization, and biological properties. Free Radic Biol Med 44 1887-1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, and Telser J (2007) Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 39 44-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Dubin AE, Bursulaya B, Viswanath V, Jegla TJ, and Patapoutian A (2008) Identification of transmembrane domain 5 as a critical molecular determinant of menthol sensitivity in mammalian TRPA1 channels. J Neurosci 28 9640-9651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Inoue R, Morii T, Takahashi N, Yamamoto S, Hara Y, Tominaga M, Shimizu S, Sato Y, and Mori Y (2006) Nitric oxide activates TRP channels by cysteine S-nitrosylation. Nat Chem Biol 2 596-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]