Abstract

Neuroactive steroids are efficacious potentiators of GABA-A receptors. Recent work has identified a site in the α1 subunit of the GABA-A receptor, that is essential for potentiation by steroids. However, each receptor contains two copies of the α1 subunit. We generated concatemers of subunits so that the α1 subunits could be mutated separately and examined the consequences of mutations that remove potentiation by most neurosteroids (α1 Q241L, α1 Q241W). Concatemers were expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes, and activation by GABA, potentiation by neurosteroids, and the agonist activity of piperidine-4-sulfonic acid (P4S) were determined. When the α1 Q241L mutation is present in α1 subunits the EC50 for activation by GABA is shifted to higher concentration and potentiation by neurosteroids is diminished. When the α1 Q241W mutation is expressed, the EC50 for GABA is shifted to lower concentration, the relative efficacy of P4S is increased, and potentiation by neurosteroids is diminished. Mutation of only one α1 subunit does not produce the full effect of mutating both sites. Overall, the data demonstrate that at a macroscopic level, the presence of a single wild-type steroid-binding site is sufficient to mediate responses to steroid, but both must be mutated to completely remove the effects of steroids. Differences between the two sites seem to be relatively subtle.

Neuroactive steroids are among the most potent and efficacious potentiators of the GABA-A receptor. They interact with portions of the receptor embedded in the plasma membrane (Akk et al., 2005), as might be expected for hydrophobic compounds. A series of experiments have supported the idea that more than one steroid-binding site is involved in producing potentiation and that the sites recognize specific features of the steroid molecule (Akk et al., 2004, 2008; Li et al., 2007a). However, a recent study found that mutation of a single residue in the α1 subunit can reduce or remove potentiation and concluded that a single site is required for potentiation (Hosie et al., 2006). There are two copies of the α subunit in each pentameric GABA-A receptor, raising the possibility that the sites may mediate distinguishable effects based on the position of the subunit in the receptor. To examine this question, we used concatemers of subunits (Im et al., 1995; Baumann et al., 2001, 2003), in which the two α1 subunits could be separately mutated and the consequences examined. We constructed two concatemers, one comprising β2-α1 subunits (amino to carboxyl termini) and the other, γ2L-β2-α1.

To examine the role of the sites, we used two mutations. The first was α1 Q241L. Previous work using free subunits has indicated that this mutation removes potentiation by preventing the effects of steroids on single channel currents (Akk et al., 2008). The concentration of GABA producing a half-maximal response is also increased (Hosie et al., 2006; Akk et al., 2008). The second was α1 Q241W. In this case, steroid potentiation is also lost (Hosie et al., 2006; Akk et al., 2008), but in records of single channel currents, the mutation mimics the presence of a bound steroid (Akk et al., 2008). The concentration of GABA producing a half-maximal response is decreased (Hosie et al., 2006; Akk et al., 2008). In addition, the α1 Q241W mutation enhances activation by the partial agonist P4S (Hosie et al., 2006; Akk et al., 2008). Accordingly, study of the α1 Q241W mutation allowed us to examine the acquisition of a steroid-mediated effect as well as the loss of one. To examine the actions of neurosteroids, we used both a 5α-reduced steroid and a 5β-reduced steroid.

Our results indicate that the presence of a single wild-type site in the GABA-A receptor can support the actions of a steroid, assayed at the level of macroscopic responses. When the α1 Q241L mutation was examined, mutation of the α1 subunit in the γ2-β2-α1 concatemer had a very small effect on all parameters measured. In contrast, mutation of the α1 subunit in the β2-α1 concatemer produced a partial effect but did not produce the full effect seen when both α subunits were mutated. When the α1 Q241W mutation was made, mutation of the α1 subunit in either concatemer produced a partial effect. Accordingly, it seems that both α1 subunits contribute to the actions of steroids. Either mutation, when placed in a single α1 subunit, had similar relative effects on activation by GABA and P4S and potentiation by a 5α- and a 5β-reduced steroid. Thus, the sites did not seem to differ in terms of their efficacy at producing one or another effect of steroids.

Materials and Methods

Concatemers were generated that were identical in sequence to those described by Baumann et al. (2002). We first generated the β2-α1 concatemer having a linker with 23 amino acid residues: Q3(Q2A3PA)2AQ5, with a FLAG tag on the N terminus of the β2 subunit between residues 4 and 5 of the mature peptide. The subunits were joined together with the linker through site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension (Ho et al., 1989) and subcloned into pcDNA3. The γ2L-β2-α1 tandem was also generated by overlap extension, joining the γ and β subunits together with the 26-amino acid residue sequence Q5A3PAQ2(QA)2A2PA2Q5. The resulting polymerase chain reaction product was subcloned into the β2-α1 concatemer. Mutated concatemers containing Q241L and Q241W were made by DNA subcloning, digesting mutated single subunits and ligating them into fragments of digested concatemers. The rat α1 subunit (kindly provided by Dr. A. Tobin, University of California, Los Angeles, CA), rat β2 subunit and rat γ2L subunit (both kindly provided by Dr. D. Weiss, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX) were used. Concatemers were generated in pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the full length of the insert was sequenced. RNA was produced using mMessage mMachine (Ambion, Austin TX). RNA was diluted in de-ionized water at a 1:1 ratio for the concatemers, and for most constructs, 2.3 ng (total DNA) in a volume of 23 nl was injected in each oocyte. Oocytes were incubated at 18°C for 1 to 3 days after injection.

We did not assay the expression levels for the constructs, but in terms of the response to 1 mM GABA, it seemed that when either mutation is in a single concatemer, surface expression is not reduced from wild-type levels (data not shown). When either mutation is present in both concatemers, expression is reduced, particularly for the α1 Q241L mutation. Accordingly, when both concatemers contained the Q241L mutation, a total of 23 ng was injected in a volume of 23 nl. The α1 Q241L mutation greatly reduced expression of free subunits in human embryonic kidney cells, whereas the Q241W mutation had lesser effects (Hosie et al., 2006).

Two-electrode voltage clamp, drug application, and data acquisition have been described previously (Li et al., 2007b; McCann et al., 2006). The peak response was obtained from an average over an interval centered at the maximal response and corrected by subtracting the mean baseline preceding the drug application. The effects of steroids were tested by coapplication with agonist, without preapplication of steroid alone. At first, the concentration-response relationship for GABA was obtained for each combination of concatemers in a group of oocytes and used to estimate a concentration of GABA that would produce a response of 5 to 10% of the maximal response. Potentiation was assessed from the peak response to GABA plus steroid divided by the peak response to that concentration of GABA alone for that oocyte. The concentration-effect relationship for GABA was normalized to the response of that oocyte to 1 mM GABA.

The amount of potentiation is strongly dependent on the level of activation produced by the given concentration of GABA alone (see Results). Because there is some variability among oocytes in the concentration-response relationship for GABA, each oocyte was tested with 1 mM GABA and other responses normalized to that. The responses to GABA alone were then corrected to the fraction of maximal response using the average fitted maximal response relative to 1 mM GABA determined from the GABA concentration-response relationships for that particular pair of concatemers (see Results). Data were not used if a response was less than 10 nA, because variability could result in large effects on calculated ratios.

Data were subsequently analyzed using pClamp (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond WA), and SigmaPlot and Systat (Systat Software, San Jose CA). Values are shown as mean ± S.E. (number of experiments).

Analysis of the Relationship between Potentiation and Activation. As described under Results, the amount of potentiation is dependent on the activation of the receptor. We have used a simple model to allow analysis of all of the data on potentiation. This model relates potentiation to activation, independent of the concentration or nature of agonist.

We neglect the complexities of the gating of GABA receptors and assume that the receptor has either an open or a closed channel. The theoretical fractional activation for a given control response (X) is

|

where kopen,X is the effective opening rate and kclose,X is the effective closing rate for that particular control response (indicated by X). An important point is that the theoretical fractional activation is not identical to our experimental fraction activation. The theoretical fractional activation has a maximal value, which can be less than 1, whereas the experimental value is defined to be 1 at the observed maximal response. For the wild-type GABA-A receptor, the maximal probability of being open is approximately 0.8 (Steinbach and Akk, 2001). This value is likely to be somewhat reduced for receptors containing the α1 Q241L mutation and increased for the α1 Q241W mutation (Akk et al., 2008), but the values are not known precisely. For this simple analysis, the maximal probability of being open is assumed to be the same for all constructs and equal to 1, and the experimental estimates have not been corrected.

To incorporate potentiation, we begin with the previous finding that potentiation of responses to GABA results from a reduction in the channel closing rate, with no change in the opening rate (Akk et al., 2004). Accordingly, for a given concentration of potentiator, the response in the presence of potentiator is

|

where Z is a factor (0 ≤ Z ≤ 1) indicating how much the effective closing rate is decreased. The ratio of the potentiated to the control response (the “potentiation ratio” plotted in the figures) is then

|

|

Because all the control and potentiated responses are paired, the equations can be simplified by defining kclose,X = L(X)kopen,X, where L(X) is a number greater than 0. This simplification results in

|

|

|

and

|

The inverse of the potentiation ratio, then, is

|

|

|

|

|

Thus, a plot of 1/PR(X) against F(X) will result in a straight line with slope (1 - Z) and intercept Z.

In this very simple model, a single parameter (Z) is used to describe the relationship between potentiation and control activation. Again, note that as a result of the assumptions, 0 ≤ Z ≤ 1. Furthermore, for a control response producing a very small fractional activation L(X) ≫ 1, so the potentiation ratio is approximately L(X)/ZL(X) or 1/Z.

Results

Choice of Mutations. The α1 Q241L and Q241W mutations were selected because they have different effects on steroid potentiation. Both essentially remove potentiation by neurosteroids (Hosie et al., 2006; Akk et al., 2008). In studies of single channel currents Q241L prevents the kinetic changes produced by steroids (Akk et al., 2008). In contrast, Q241W mimics the kinetic changes produced by steroids and prevents additional potentiation (Akk et al., 2008). The Q241L mutation shifts the EC50 for activation by GABA to higher concentrations, probably as a result of decreased mean open duration (Akk et al., 2008). Q241W shifts the EC50 for activation by GABA to lower concentrations, probably as a result of increased mean open duration (Akk et al., 2008). The effects of Q241L on activation by P4S have not been studied, but Q241W enhances activation in single-channel currents (Akk et al., 2008) and increases the maximal response to P4S relative to the maximal GABA response (Hosie et al., 2006). Based on these considerations, it seemed that it would be possible to compare consequences of mutations that had qualitatively opposite effects.

The role of the α1 Gln241 residue is not completely clear. Recent studies have indicated that this residue may not solely provide a binding site for steroids but may also be important for shaping the structure of the first transmembrane helix of the subunit (Akk et al., 2008).

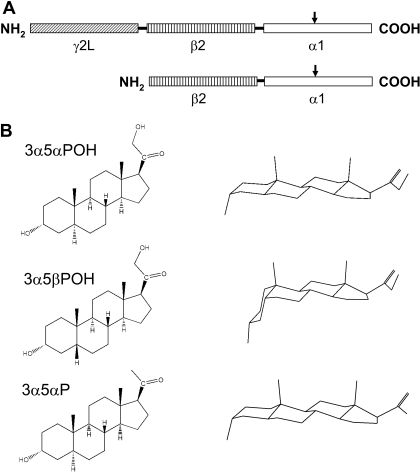

Concatemers Containing Wild-Type α1 Subunits. The structure of the concatemers is summarized in Fig. 1, with the structures of the steroids tested. Traces of representative recordings from oocytes are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The structures of the concatemers and the steroids used. A, the concatemers used and the approximate location of the mutations (arrows). B, structures of the steroids used (left column as flat structures and right column as three-dimensional views).

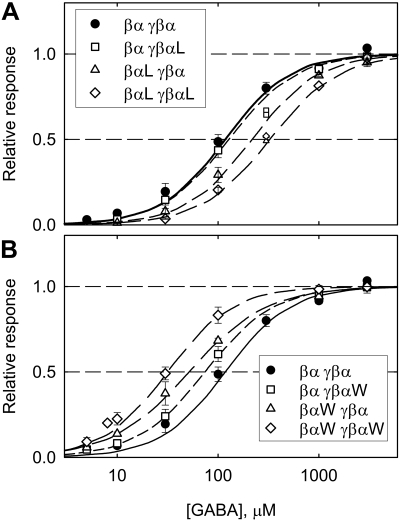

The concentration-response relationship for activation by GABA (Fig. 2) was fit with the Hill equation (I = Imax {([GABA]/EC50) nH}/{1 + ([GABA]/EC50)nH}), where I is the response to a given concentration of GABA, Imax is the fit maximal response, EC50 is the concentration of GABA producing a half-maximal response, and nH is the Hill coefficient. Mean values for fit parameters are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Normalized concentration-response curves for responses to GABA. A, data for wild-type concatemers and concatemers containing the α1 Q241L mutation. The presence of the mutation in the βα concatemer or in both concatemers shifts the curve to higher [GABA]. B, data for wild-type concatemers and concatemers containing the α1 Q241W mutation. The presence of the mutation in either or both concatemers shifts the curve to lower [GABA]. The curves show fits of eq. 1 (values shown in Table 1). For easier comparison of the curves, the data have been normalized to the fit maximal amplitude for display in the figure (fit maximal amplitudes are shown in Table 1). Points show mean ± S.E. for 3 to 15 oocytes (small symbols in A show data for single oocytes).

TABLE 1.

Receptor activation by GABA and P4S

The first column shows the constructs injected. The next three columns show the Hill coefficient, EC50, and maximal amplitude relative to 1 mM GABA for fits of the Hill equation (I = Imax {([GABA]/EC50)nH}/{1 + ([GABA]/EC50)nH}) to concentration-response data for GABA. The final column shows the relative response to 1 mM P4S compared with the response (for the same oocyte) to 1 mM GABA. Values shown are mean ± S.E. (number of oocytes), probability for a significant difference to βα γβα. Probabilities Dunnett correction after ANOVA to correct for multiple comparisons.

| Constructs | GABA nH | GABA EC50 | Imax | P4S Gating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μM | ||||

| βα γβα | 1.35 ± 0.06 (15),— | 118 ± 16 (15),— | 1.06 ± 0.02 (15),— | 0.04 ± 0.01 (8),— |

| βα γβαL | 1.30 ± 0.05 (6) ns | 128 ± 19 (6) ns | 1.09 ± 0.01 (6) ns | 0.04 ± 0.01 (6) ns |

| βαL γβα | 1.32 ± 0.07 (6) ns | 218 ± 36 (6)** | 1.15 ± 0.03 (6) ns | 0.02 ± 0.00 (6) ns |

| βαL γβαL | 1.27 ± 0.09 (5) ns | 327 ± 34 (5)*** | 1.26 ± 0.06 (5)*** | 0.01 ± 0.00 (8) ns |

| βα γβαW | 1.27 ± 0.11 (5) ns | 74 ± 11 (5) ns | 1.04 ± 0.02 (5) ns | 0.13 ± 0.03 (6) ns |

| βαW γβα | 1.13 ± 0.06 (4) ns | 52 ± 3 (4) ns | 1.06 ± 0.02 (4) ns | 0.17 ± 0.03 (7)** |

| βαW γβαW | 1.34 ± 0.08 (9) ns | 32 ± 4 (9)** | 0.99 ± 0.01 (9) ns | 0.45 ± 0.05 (8)*** |

—, not applicable; ns, P > 0.05.

* P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

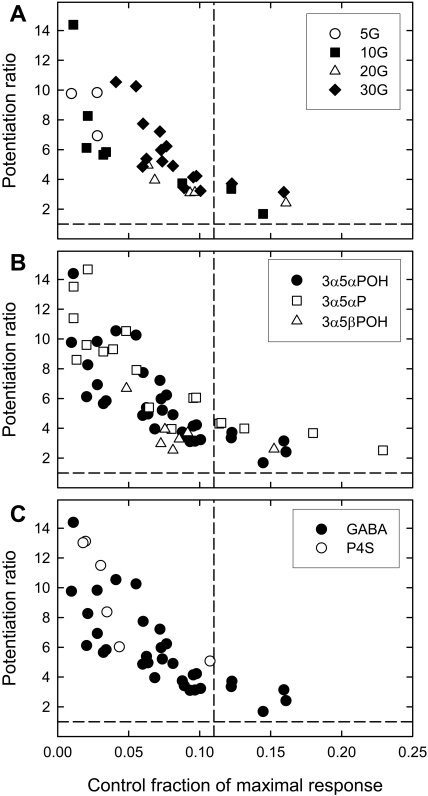

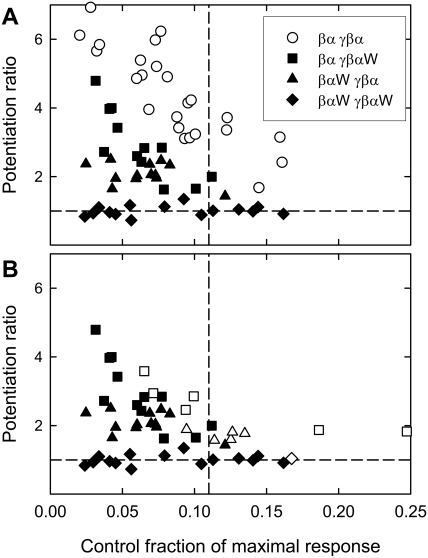

One micromolar (3α,5α)-3,21-dihydroxypregnan-20-one (3α5αPOH) potentiates responses to low concentrations of GABA quite effectively (Fig. 3A). The data in Fig. 3A show the potentiation ratio (defined as the ratio of the response to a given [GABA] in the presence of steroid to the response to a given [GABA] in the absence of steroid) plotted against the fraction of maximal response elicited by that [GABA] in the absence of steroid. It is clear that potentiation depends strongly on the fractional activation by the control response and is absent for responses producing a large fractional activation (e.g., 1 mM GABA; Table 2). Because of some variability in the concentration-response curves for GABA among oocytes, the data will be presented in terms of control fractional activation rather than the [GABA] used to elicit the response. On average, for control responses producing less than 0.11 of the maximal response, 1 μM 3α5αPOH increases the response by 6.3 ± 0.5-fold (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Potentiation of wild-type concatemers by neurosteroids. The figure shows the potentiation ratio plotted against the fraction of maximal response for the control response for wild-type concatemers. A, potentiation produced by 1 μM 3α5αPOH for responses elicited by different concentrations of GABA. B, potentiation by 1 μM 3α5αPOH, 1 μM 3α5βPOH, and 1 μM 3α5αP (data for responses elicited by all concentrations of GABA). C, potentiation by 1 μM 3α5αPOH for responses elicited by a low concentration of GABA (•) and by 1 mM P4S (○). The data for the two sets overlap. Each point is the response of an oocyte. The dashed lines show a potentiation ratio of one (that is, no potentiation) and a fraction of maximal response of 0.11 (the cutoff for the means presented in Table 3). Mean potentiation ratios are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Potentiation of responses to high agonist concentrations

The first column shows the constructs injected. The second column shows the potentiation ratio for responses to 1 mM GABA produced by 1 μM 3α5αPOH. The second column shows data for responses to 1 mM P4S. Note that for this table, potentiation of all responses has been averaged, rather than only for control responses below a criterion (see Results). Values shown are mean ± S.E., with the number of oocyte in parentheses, probability for a significant difference from βα γβα, and probability that the potentiation ratio is significantly different from 1 (that is, no effect). Comparisons among groups have a Dunnett correction after ANOVA to correct for multiple comparisons. Individual values are shown when only two oocytes were studied.

| Constructs | 1 mM GABA + 1 μM 3α5αPOH | 1 mM P4S + 1 μM 3α5αPOH |

|---|---|---|

| βα γβα | 1.05 ± 0.04 (5)—ns | 9.52 ± 1.44 (6)—** |

| βα γβαL | 0.86 ± 1.01 (2) | 6.34 ± 0.89 (6)*** |

| βαL γβα | 1.04 ± 1.06 (2) | 4.78 ± 0.77 (6)***** |

| βαL γβαL | 0.73 ± 1.01 (2) | 1.51 ± 0.23 (7)*** ns |

| βα γβαW | 0.92 ± 0.02 (4) ns* | 2.59 ± 0.28 (6)***** |

| βαW γβα | 1.00 ± 0.02 (4) ns ns | 1.60 ± 0.09 (7)****** |

| βαW γβαW | 0.94 ± 0.02 (5) ns* | 0.98 ± 0.01 (8)*** ns |

—, not applicable; ns, P > 0.05.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

TABLE 3.

Potentiation of responses to a low concentration of GABA

The columns show the potentiation ratio produced by co-application of 1 μM steroid. The means are computed for control responses producing less than 0.11 of the maximal response from that oocyte (see Results and Figures 3, 4 and 5). Values shown are mean ± S.E., with the number of oocyte in parentheses, probability for a significant difference from βα γβα, and probability that the potentiation ratio is significantly different from 1 (that is, no effect). Comparisons among groups have a Dunnett correction after ANOVA to correct for multiple comparisons. Individual value shown when only one oocyte had a control fractional response less than 0.11 (see Supplementary Figure 2).

| Constructs | 3α5αPOH | 3α5βPOH | 3α5αP |

|---|---|---|---|

| βα γβα | 6.26 ± 0.53 (27)—*** | 3.85 ± 0.60 (6)—** | 10.98 ± 1.64 (15)—*** |

| βα γβαL | 6.16 ± 0.75 (17) ns*** | 3.43 ± 0.29 (6) ns*** | 5.68 (1) |

| βαL γβα | 3.40 ± 0.33 (13)****** | 2.08 ± 0.11 (5)****** | 3.32 ± 0.29 (4)*** |

| βαL γβαL | 1.13 ± 0.06 (18)**** | 1.09 ± 0.08 (7)*** ns | 1.13 ± 0.09 (6)** ns |

| βα γβαW | 2.99 ± 0.30 (11)****** | 1.86 ± 0.13 (6)***** | — |

| βαW γβα | 2.14 ± 0.08 (12)****** | 1.49 ± 0.03 (8)****** | — |

| βαW γβαW | 1.01 ± 0.05 (11)*** ns | 0.81 ± 0.04 (8)***** | — |

—, not applicable; ns, P > 0.05.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

Similar results were obtained with a second potentiating steroid, (3α,5α)-3-hydroxypregnan-20-one (allopregnanolone; 3α5αP), and a 5β-reduced steroid, (3α,5β)-3,21-dihydroxypregnan-20-one (3α5βPOH) (Fig. 3B; mean values in Table 3).

The partial agonist P4S was tested only at a high concentration, 1 mM, which should produce a maximal, albeit small, response (Ebert et al., 1994). As summarized in Table 1, P4S elicits a small maximal response. One micromolar 3α5αPOH potentiates the responses to 1 mM P4S (Fig. 3C, Table 2). This contrasts with the observation that 3α5αPOH does not potentiate the responses to 1 mM GABA (Table 2). This difference is expected and reflects the fact that P4S produces a low maximal probability of being open (Steinbach and Akk, 2001). It is interesting that the data for P4S and for GABA superimpose when potentiation is plotted as a function of control fractional activation (Fig. 3C).

Concatemers Containing α1 Subunits with the Q241L Mutation. The consequences of the α1 Q241L mutation in individual subunits were examined using two concatemers, γ2L-β2-α1(Q241L) [γβα(Q241L)] and βα(Q241L). The four concatemers, two containing mutations and two wild-type, were expressed to produce all possible combinations of α1 mutations: γβα(Q241L)-βα, γβα-βα(Q241L), and γβα(Q241L)-βα(Q241L).

When both concatemers contain the mutation, the EC50 for activation by GABA is increased approximately 2.8-fold (Fig. 2, Table 1). The effect of placing the mutation solely in the γβα(Q241L) concatemer is very small. The effect is larger when the mutation is only in βα(Q241L) but not as large as when present in both concatemers.

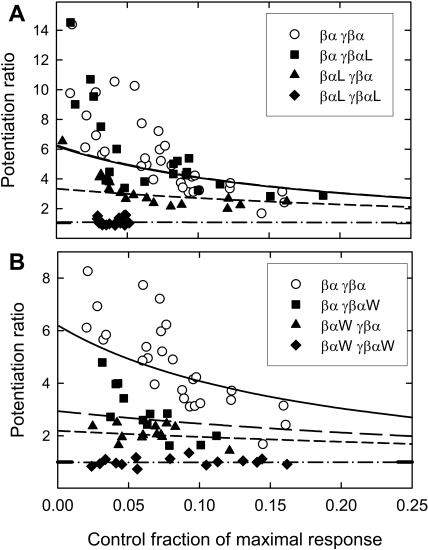

Potentiation by 1 μM 3α5αPOH, 3α5αP, and 3α5βPOH is greatly reduced when the mutation is present in both concatemers (Fig. 4, Table 3 and Supplemental Fig. 2), as expected from expression of free subunits. However, removal of a single site does not cause loss of potentiation. Indeed, removal of one site by expression of the γβα(Q241L)-βα concatemers has a minimal effect on potentiation, whereas expression of the γβα-βα(Q241L) concatemers produces a partial reduction (Fig. 4 and Table 3). Clearly, potentiation can be mediated by a wild-type site in either α1 subunit.

Fig. 4.

Potentiation of concatemers containing the α1 Q241L mutation by neurosteroids. Data are shown as in Fig. 3. A, data for potentiation by 1 μM 3α5αPOH. Note that the points for oocytes injected with the βα γβαL constructs overlap the data for wild-type concatemers. The presence of the mutation in the βαL or both concatemers reduces the potentiation ratio at similar levels of control activation. Similar data were obtained for potentiation by 1 μM 3α5βPOH and 1 μM 3α5αP (Supplementary Fig. 2; mean data in Table 3). B, potentiation by 1 μM 3α5αPOH for responses elicited by a low concentration of GABA (filled symbols, defined in A) and by 1 mM P4S (empty symbols). Potentiation for responses to GABA and P4S is affected essentially equivalently by the mutations.

P4S is an inefficacious agonist for concatemers containing the α1 Q241L mutation (Table 1), as for the wild-type concatemers. To discount the possibility that the mutation shifted the EC50 so that 1 mM P4S is no longer saturating, we tested the response to 10 mM P4S of one oocyte injected with the γβα(Q241L)-βα(Q241L) combination. The response was approximately 1.2-fold times the response to 1 mM P4S. This observation suggests that no major shift occurred, and that 1 mM P4S is still saturating for activation.

However, 3α5αPOH no longer potentiates the response to 1 mM P4S when both concatemers contain the mutation (Table 2). When only a single α1 subunit is mutated, the effects are similar to those for potentiation of responses to GABA. There is no apparent reduction in the case of the γβα(Q241L)-βα concatemers and a partial reduction for the γβα-βα(Q241L) concatemers (Fig. 4B, Table 2).

Concatemers Containing α1 Subunits with the Q241W Mutation. In contrast to the α1 Q241L mutation, the α1 Q241W mutation seems to occlude potentiation by mimicking a bound steroid molecule (Akk et al., 2008). We tested the possible combinations of concatemers containing the α1 Q241W mutation, γβα(Q241W)-βα, γβα-βα(Q241W), and γβα(Q241W)-βα(Q241W).

When both concatemers contain the mutation, the EC50 for GABA is decreased by approximately 3.7-fold (Fig. 2, Table 1). Placing the mutation in a single concatemer alone shifts the EC50 in the same direction but to a lesser extent.

Potentiation by 1 μM 3α5αPOH and 3α5βPOH is abolished when the mutation is present in both concatemers (Fig. 5A, Table 3, and Supplemental Fig. 3), in agreement with studies of expression of free subunits. However, mutation of a single site does not cause loss of potentiation. Instead, receptors containing a single mutated α1 subunit show a partial reduction in potentiation. In the case of this mutation, the reduction is similar for either single mutation. However, again potentiation can be mediated by a wild-type site in either α1 subunit.

Fig. 5.

Potentiation of concatemers containing the α1 Q241W mutation by neurosteroids. Data are shown as in Fig. 3. A, data for potentiation by 1 μM 3α5αPOH. Similar data were obtained for potentiation by 1 μM 3α5βPOH (Supplementary Fig. 3; mean data in Table 3). B, potentiation by 1 μM 3α5αPOH for responses elicited by a low concentration of GABA (filled symbols, defined in A) and by 1 mM P4S (empty symbols). Potentiation for responses to GABA and P4S is affected essentially equivalently by the mutations.

The agonist efficacy of P4S is greatly increased by the presence of the α1 Q241W mutation in both concatemers (Table 1), and 3α5αPOH no longer potentiates the response to 1 mM P4S (Fig. 5B, Table 2). Because the response to 1 mM P4S is increased so much when the α1 Q241W mutation is in both concatemers, we also tested potentiation of responses to 10 μM P4S. In this case, the control response as a fraction of maximal response is only 0.04 ± 0.00 (three oocytes), whereas potentiation is still absent (1.04 ± 0.06). When the mutation is present in a single subunit, the relative response to 1 mM P4S is increased but not as much as when the mutation is present in both (Table 1). As is seen for potentiation by GABA, potentiation of responses to 1 mM P4S is reduced but not completely lost when only a single α1 subunit is mutated (Fig. 5, Table 3), and the reduction is more marked when the mutation is the in βα(Q241W) concatemer.

Analysis of the Relationship between Potentiation and Activation. At present, our understanding of the kinetic mechanisms for either activation or potentiation of the GABA-A receptor is too incomplete to allow a full analysis of the relationship between potentiation and activation. However, it is highly desirable to have an approach that would allow use of all the data on potentiation. As described under Materials and Methods, a simple model can provide an initial analysis. This model relates potentiation to activation, independent of the concentration or nature of agonist. A single parameter Z (how much the effective closing rate is decreased by a potentiating steroid) is used to describe the relationship.

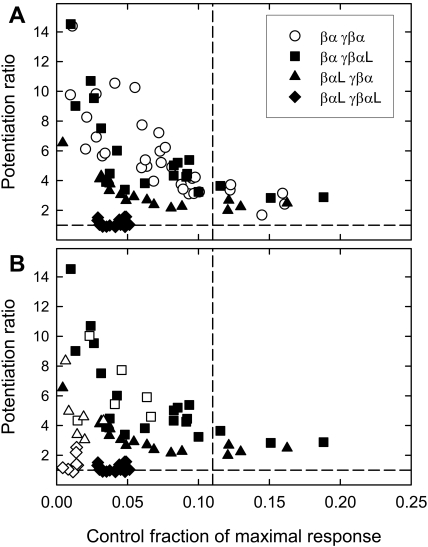

The data for potentiation by 1 μM 3α5αPOH were fit to estimate the value of Z (reduction of the closing rate). The lines shown in Fig. 6 are the predicted curves for this single parameter fit, and values for Z are shown in Table 4. This analysis captures most features of the data, including the general shape of the curves and the effects of the mutations. However, the data also suggest that the model is too simple. The major deviation is that potentiation at very low activation is underestimated. This might suggest that potentiation at very low activation is more efficacious than at greater levels of activation, perhaps as a result of some dependence of steroid binding or potentiation on the state of the GABA-A receptor.

Fig. 6.

Fits of a simple model for potentiation. Data are shown for potentiation of responses to low concentrations of GABA by 1 μM 3α5αPOH. A, data for wild-type concatemers and concatemers containing the α1 Q241L mutation. The fitted curves are shown by the lines (solid, wild-type; long dash, βα γβαL; short dash, βαL γβα; dash-dot, βαL γβαL). Note that the lines for βα γβαL and wild-type concatemers overlap. B, similar data for wild-type concatemers and concatemers containing the α1 Q241W mutation. The ordinal scales in A and B are different.

TABLE 4.

Fit values for Z

Shown are the data for potentiation of responses to low concentrations of GABA and for responses to 1 mM P4S. Each column shows the fit value for Z ± S.E. of the fit, the number of data pairs fit in parentheses, and the inverse of Z, which gives the slowing of the closing process. 3α5βPOH consistently reduced responses to low concentrations of GABA for oocytes injected with βαW γβαW concatemers (Table 2).

| Construct | GABA + 1 μM 3α5αPOH | GABA + 1 μM 3α5βPOH | GABA + 1 μM 3α5αP | 1 mM P4S + 1 μM 3α5αPOH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| βα γβα | 0.16 ± 0.02 (40) 6.2× | 0.23 ± 0.03 (7) 4.3× | 0.10 ± 0.01 (23) 9.9× | 0.08 ± 0.01 (6) 12.3× |

| βα γβαL | 0.16 ± 0.02 (24) 6.3× | 0.27 ± 0.03 (6) 3.8× | 0.13 ± 0.02 (6) 7.7× | 0.14 ± 0.02 (6) 7.4× |

| βαL γβα | 0.30 ± 0.02 (19) 3.3× | 0.46 ± 0.02 (5) 2.2× | 0.26 ± 0.02 (6) 3.8× | 0.22 ± 0.03 (6) 4.6× |

| βαL γβαL | 0.92 ± 0.04 (20) 1.1× | 0.95 ± 0.08 (7) 1.1× | 0.90 ± 0.06 (6) 1.1× | 0.75 ± 0.10 (7) 1.3× |

| βα γβαW | 0.34 ± 0.04 (16) 2.9× | 0.53 ± 0.04 (7) 1.9× | — | 0.32 ± 0.03 (6) 3.1× |

| βαW γβα | 0.46 ± 0.02 (17) 2.2× | 0.65 ± 0.02 (8) 1.5× | — | 0.56 ± 0.03 (7) 1.8× |

| βαW γβαW | 1.01 ± 0.04 (21) 1.0× | — | — | 0.99 ± 0.03 (11) 1.0× |

—, not applicable.

The inverse of Z is very close to the mean potentiation calculated for small responses (compare Tables 2 and 4). This relationship makes sense, because the fractional activation for a small response is close to the ratio of the opening to the closing rates (see Materials and Methods). In this analysis, potentiation is postulated to result from a decrease in the closing rate, and so it would be predicted that potentiation would increase the response by 1/Z-fold. Overall, this analysis uses all of the data available, irrespective of the control activation, and results in similar observations as the earlier analysis of potentiation of small responses.

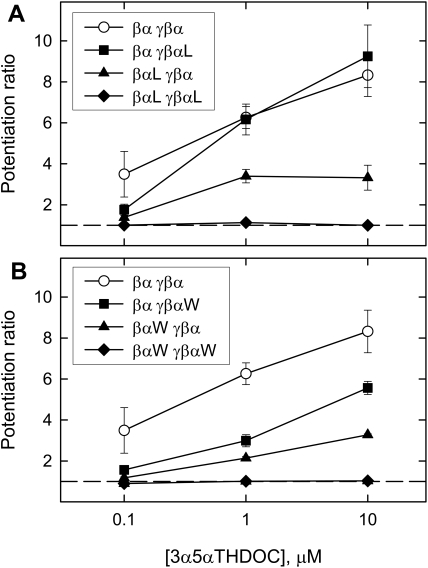

Relationship between Potentiation and [3α5αPOH]. We performed a preliminary study of the relationship between potentiation and [3α5αPOH], as shown in Fig. 7. Ten micromolar 3α5αPOH was the highest concentration tested because of the low aqueous solubility of the steroid. The presence of either mutation in both α1 subunits essentially removes potentiation even by 10 μM 3α5αPOH. The combination of βα and γβα(Q241L) results in no change from wild-type, whereas the βα(Q241L)-γβα combination shows a possible reduction in efficacy. With the α1 Q241W mutation in a single concatemer, responses are reduced approximately equally at all concentrations tested. It seems likely that there is a reduction in potency, although there may also be a reduction in efficacy. Overall, these results confirm that observations made with 1 μM 3α5αPOH are valid indications of ability of steroids to potentiate, and suggest that changes can occur in both efficacy and potency.

Fig. 7.

The concentration-effect relationship for 3α5αPOH potentiation of responses elicited by GABA. The data are means for control fractional activation less than 0.11. Points show mean ± S.E. for 3 to 27 oocytes. Data points at 0.1 and 10 μM for βαl-γβα and βαW-γβαW constructs are the means ± S.D. for responses from two oocytes only. The lines simply connect the points.

Amplitude of the Potentiated Response. It is possible that the observed potentiation could be truncated by the maximal response of the receptors. This does not seem to be the case, because the potentiated responses for responses elicited by low [GABA] were less than half of the maximal response for that oocyte (the mean potentiated response in the presence of 1 μM 3α5αPOH is for γβα-βα 0.36 ± 0.02 of maximum, and for γβαl-βαL it is 0.05 ± 0.00, whereas other combinations of concatemers produced intermediate values). Furthermore, the data in Fig. 7 suggest that 1 μM 3α5αPOH does not produce a maximal potentiation for most combinations of concatemers, indicating that it is not a supersaturating concentration. Hence, either increases or decreases in potentiation should be observable in the data.

Discussion

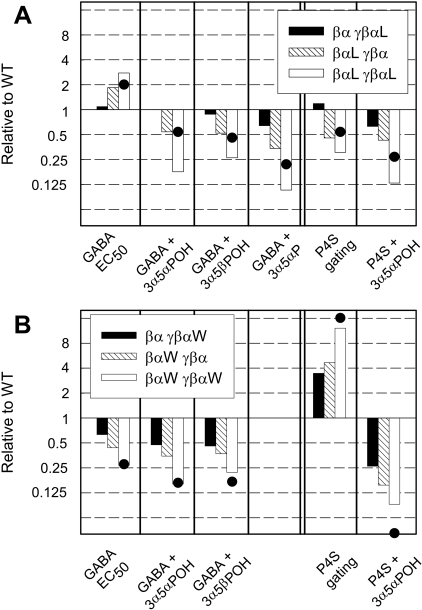

We examined whether the two α1 subunits in a GABA-A receptor are distinct in terms of the proposed steroid-binding site by expressing concatemers of subunits and selectively mutating individual α1 subunits. The data indicate that the properties of the sites are similar in terms of steroid recognition and functional effects and that the presence of either site can support potentiation. The effects of mutations on the multiple assays performed are summarized in Fig. 8, in terms of the ratio of the effect on a given construct to the effect on receptors containing wild-type concatemers.

Fig. 8.

The effects of the mutations in specific α1 subunits. This figure shows the ratios of parameters to the value for wild-type concatemers, expressed on a logarithmic scale, so that the overall pattern of effects can be readily compared. Data for concatemers containing the α1 Q241L mutation (A) and for concatemers containing the α1 Q241W mutation (B). The parts of each panel show the relative EC50 for activation by GABA (part 1; values in Table 1), the mean potentiation ratios for responses elicited by low concentrations of GABA (parts 2-4, Tables 3 and 4), relative gating by 1 mM P4S (part 5, Table 1) and potentiation of responses to 1 mM P4S (part 6, Tables 2 and 4). The effect ratios for potentiation are calculated using the average of the potentiation ratio and the inverse of Z. Two qualitative points are illustrated in the Figure. First, the effect of a mutation in the γβα concatemer (black bars) is consistently less than the effect of the same mutation in the βα concatemer (hatched bar). Second, for the α1 Q241W mutation (B), the product of the effect ratios for mutations in single α1 subunits (the sum of the logarithms of the effect ratios, shown by •) is close to the effect seen when the mutation is present in both concatemers. However, this is not seen for the Q241L mutation (A), for which the presence of the mutation in both concatemers leads to a larger effect than expected.

Effects of Mutations on Activation by GABA and P4S

α1 Q241L and Q241W have opposite effects on the durations of openings produced by GABA, which are likely to underlie the changes in the macroscopic concentration-effect curve. When a potentiating steroid is applied to a wild-type receptor, the open durations are prolonged as well (Akk et al., 2004), and the EC50 for the macroscopic gating curve for GABA is shifted to lower concentration. Accordingly, it seemed possible that the effects on steroid potentiation and GABA activation are mechanistically related and that tryptophan at position 241 might mimic a bound steroid agonist, whereas leucine might mimic an inverse agonist. However, it is unlikely that leucine acts as an inverse agonist. The first reason is that Q241S and Q241T also shift the EC50 for GABA activation to the same extent as Q241L but do not remove potentiation (Hosie et al., 2006). The second is that one steroid analog is able to potentiate receptors that contain the α1 Q241L mutation (Akk et al., 2008). Accordingly, it seems that mutations to α1 Gln241 can have separable effects on activation by GABA and potentiation by steroids. The possibility that the Q241W mutation acts as a (partial) steroid mimic will be considered further, below.

When the α1 Q241L mutation is in the γβα concatemer, there is a minimal effect on the EC50 for GABA, whereas the mutation in the βα concatemer produces an increase, and the mutation in both concatemers a greater increase. The presence of the Q241W mutation in either single concatemer produces a reduction in the EC50, although the mutation in the βα concatemer produces a larger effect. One interpretation is that the Q241W mutation does mimic, at least in some respects, the presence of a bound steroid potentiator. We have found that a steroid can potentiate even when only one site is intact, so the change in GABA potency may reflect the gating changes produced by mimicry of one or two steroid molecules bound to the receptor. In the case of the Q241L mutation, it may be that the difference in the changes in the EC50 arises from interactions between the α1 subunit and adjacent subunits.

We tested responses to a single, high concentration of P4S to estimate the potency of P4S compared with GABA. The α1 Q241L mutation resulted in nonsignificant decreases in the relative response to 1 mM P4S. Based on previous studies, we had expected that the Q241W mutation would increase the relative efficacy for P4S. This expectation was confirmed. Again, when a single subunit is mutated, a partial effect results.

Effects of Mutations on Potentiation by Steroids

Either α1 Mutation Essentially Removed Potentiation When Present in Both Concatemers. We tested both a5α-anda5β-reduced steroid for potentiation of responses to low concentrations of GABA because these steroids differ in terms of the planarity of the steroid core ring system (Fig. 1). However, no major difference was seen between the effects of selective mutations on potentiation by the two steroids. For all the constructs tested, at 1 μM the 5β-reduced steroid produces approximately 70% of the potentiation by the 5α-reduced steroid.

The α1 Q241L mutation has little effect on potentiation of responses to GABA when it is placed in the γβα concatemer and stronger effects when placed in the βα concatemer. The α1 Q241L mutation also reduces potentiation of responses to 1 mM P4S by 3α5αPOH.

The α1 Q241W mutation reduces potentiation of responses to GABA when present in either concatemer. The α1 Q241W mutation also reduces potentiation of responses to a maximal concentration of P4S. However, the mutation has a major effect to enhance the relative efficacy of P4S. If both effects result from the mutation mimicking a bound steroid, then it might be expected that they would be multiplicative: the enhancement of potency would occlude the increase as a result of potentiation, and the overall activation as a fraction of maximal response would be constant. This expectation is qualitatively correct (see Table 5). These results clearly distinguish the consequences of the two mutations, as the Q241L mutation reduces the potentiated response and are consistent with the idea that the α1 Q241W mutation does mimic a bound steroid.

TABLE 5.

Average amplitude of potentiated responses to 1 mM P4S

The average fractional activation for responses to 1 mM P4S plus 1 μM 3α5αPOH are shown. Note that the Q241L mutation progressively reduces the average fractional activation, whereas the Q241W mutation results in relatively constant overall levels of activation. Values shown are mean ± S.E. with the number of oocyte in parentheses.

| Constructs | 1 mM P4S + 1 μM 3α5αPOH |

|---|---|

| βα γβα | 0.32 ± 0.05 (6) |

| βα γβαL | 0.26 ± 0.05 (6) |

| βαL γβα | 0.07 ± 0.02 (6) |

| βαL γβαL | 0.02 ± 0.00 (7) |

| βα γβαW | 0.29 ± 0.04 (6) |

| βαW γβα | 0.25 ± 0.03 (7) |

| βαW γβαW | 0.44 ± 0.05 (8) |

Overall Effects of Mutations in Individual α1 Subunits. The major point is that neither mutation in a single α1 subunit produces the full effect seen when mutations are in both α1 subunits. In particular, for potentiation by neurosteroids, a wild-type α1 subunit in either position in the receptor is able to support potentiation by both 5α- and 5β-reduced steroids. Hence, either site can mediate at least partial potentiation. However, the removal of a single site cannot produce the effects of mutating both sites, indicating that both sites are involved in producing the full effects on a wild-type receptor.

A second general point is that the effect of a single mutation seems to be greater when the mutation is present in the βα concatemer than the γβα. The differences do not reach statistical significance, but for a total of 11 comparisons, the effect of a mutation in the γβα concatemer is less than that of a mutation in the βα concatemer for every assay. The likelihood that this would occur by chance is less than 0.0005 (that is, 0.511, with the null hypothesis that the effects are equal and any difference is random). However, the reason for the trend is not clear. It might be that there are subtle differences between the two sites in terms of steroid interactions. An alternative, however, is that the difference arises from the properties of the adjacent β subunits and interactions among subunits. In the assembled receptor, the α subunit in the βα concatemer is flanked by a γ and a β subunit, whereas the other has β subunits on both sides. We have already argued that the shift in the GABA EC50 produced by the Q241L mutation is probably an independent action from the reduction in steroid potentiation. The observation that this effect shows the same positional sensitivity might support this interpretation that intersubunit interactions underlie the differences. It has also been reported that the two β subunits are not identical in terms of agonist-binding and receptor activation (Baumann et al., 2003). Further experiments will be required to examine coupling to agonist binding and receptor activation, and overall interactions among adjacent subunits.

The observations with the two mutations are complementary. The α1 Q241L mutation seems to prevent effective interaction between the receptor and the steroid, whereas the Q241W mutation seems to mimic a steroid. In either case, mutation of the site in the βα concatemer produced stronger effects than the mutations in the γβα concatemer.

Inspection of Fig. 8 shows a pattern for the effects of the Q241L mutation—the effect when the mutation is present in both concatemers is larger than the sum of the effects for each concatemer separately. Indeed, this is the case for all six assays, in contrast to the results for the Q241W mutation. If the mutations in the two α subunits contribute independently to the overall function of the receptor, then the logarithms of the effect ratios should add. This is based on the idea that the energetic contributions to the overall functional equilibrium would sum if the mutations had independent effects. The difference in effect between the double mutation and the sum of the two single mutations can be interpreted in terms of a “coupling energy” as for mutant-cycle analysis (LiCata and Ackers, 1995). In the present work the two α subunits are widely separated, in contrast to many studies of coupling energy, which have emphasized residues in close proximity, and it has been proposed that nonadditivity for distant residues should be assessed using the criterion that the coupling energy be greater than 20% of the energy change for the double mutation (Istomin et al., 2008). On this basis, all assays for the Q241L mutation show nonadditive effects. However, we note that all of the calculated energy changes are relatively small, with an average change of approximately 0.9 or 1.1 kCal/mol (absolute value) for the double mutations and 0.4 or 0.1 kCal/mol coupling energy for the Q241L or Q241W mutations, respectively. If the Q241W mutation does mimic the presence of a steroid, these results suggest that occupation of the sites makes essentially independent contributions to function. In contrast, the results for the Q241L mutation are consistent with the idea that the functional properties of the receptor result from global function and include subunit interactions.

The major conclusions from these studies are that the sites on the two α1 subunits are similar in the assays used. Either site can support steroid potentiation, and the relatively subtle differences found may reflect interactions with adjacent subunits. The remaining caveat is that studies of single channel currents have found that steroids have more than one effect on the kinetics of currents elicited by agonists, and each of the actions can result in macroscopic potentiation. It will be valuable to examine single channel currents from concatemeric constructs to determine whether the sites are distinguishable with more precise measurements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gustav Akk for advice and comments during the study and on the manuscript. We thank Drs. Chuck Zorumski and Steve Mennerick for providing Xenopus laevis oocytes.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [GM47969].

ABBREVIATIONS: 3α5αPOH, (3α,5α)-3,21-dihydroxypregnan-20-one; 3α5αP, (3α,5α)-3-hydroxypregnan-20-one; 3α5βPOH, (3α,5β)-3,21-dihydroxypregnan-20-one; P4S, piperidine-4-sulfonic acid; γβα(Q241L), γ2L-β2-α1(Q241L).

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

References

- Akk G, Bracamontes JR, Covey DF, Evers A, Dao T, and Steinbach JH (2004) Neuroactive steroids have multiple actions to potentiate GABA-A receptors. J Physiol 558 59-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akk G, Li P, Bracamontes J, Reichert DE, Covey DF, and Steinbach JH (2008) Mutations of the GABA-A receptor α1 subunit M1 domain reveal unexpected complexity for modulation by neuroactive steroids. Mol Pharmacol 74 614-627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akk G, Shu HJ, Wang C, Steinbach JH, Zorumski CF, Covey DF, and Mennerick S (2005) Neurosteroid access to the GABA-A receptor. J Neurosci 25 11605-11613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann SW, Baur R, and Sigel E (2001) Subunit arrangement of γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. J Biol Chem 276 36275-36280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann SW, Baur R, and Sigel E (2002) Forced subunit assembly in α1β2γ2 GABA-A receptors. Insight into the absolute arrangement. J Biol Chem 277 46020-46025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann SW, Baur R, and Sigel E (2003) Individual properties of the two functional agonist sites in GABA-A receptors. J Neurosci 23 11158-11166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert B, Wafford KA, Whiting PJ, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, and Kemp JA (1994) Molecular pharmacology of γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor agonists and partial agonists in oocytes injected with different α, β, and γ receptor subunit combinations. Mol Pharmacol 46 957-963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, and Pease LR (1989) Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77 51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, da Silva HM, and Smart TG (2006) Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABA-A receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature 444 486-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im WB, Pregenzer JF, Binder JA, Dillon GH, and Alberts GL (1995) Chloride channel expression with the tandem construct of α6-β2 GABA-A receptor subunit requires a monomeric subunit of α6 or γ2. J Biol Chem 270 26063-26066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istomin AY, Gromiha MM, Vorov OK, Jacobs DJ, and Livesay DR (2008) New insight into long-range nonadditivity within protein double-mutant cycles. Proteins 70 915-924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Bracamontes J, Katona BW, Covey DF, Steinbach JH, and Akk G (2007a) Natural and enantiomeric etiocholanolone interact with distinct sites on the rat α1β2γ2L GABA-A receptor. Mol Pharmacol 71 1582-1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Jin X, Covey DF, and Steinbach JH (2007b) Neuroactive steroids and human recombinant ρ1 GABAC receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323 236-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LiCata VJ and Ackers GK (1995) Long-range, small magnitude nonadditivity of mutational effects in proteins. Biochemistry 34 3133-3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann CM, Bracamontes J, Steinbach JH, and Sanes JR (2006) The cholinergic antagonist α-bungarotoxin also binds and blocks a subset of GABA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 5149-5154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach JH and Akk G (2001) Modulation of GABA-A receptor gating by pentobarbital. J Physiol 537 715-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.