Abstract

Little is known about the genetic basis of sex determination in vertebrates though considerable progress has been made in recent years. In this study, segregation analysis and linkage mapping were performed to localize an amphibian sex-determining locus (ambysex) in the tiger salamander (Ambystoma) genome. Segregation of sex phenotypes (male, female) among 2nd generation individuals of interspecific crosses (A. mexicanum x A. t. tigrinum) was consistent with Mendelian expectations, although a slight female bias was observed. Individuals from these same crosses were typed for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) distributed throughout the genome to identify molecular markers for ambysex. A marker (E24C3) was identified approximately 5.9 cM from ambysex. Linkage of E24C3 to ambysex was independently validated in a second, intraspecific cross (A. mexicanum). Interestingly, ambysex locates to the tip of one of the larger linkage groups of the Ambystoma meiotic map. Considering that this location does not show reduced recombination, we speculate that the ambysex locus may have arisen quite recently, within the last few million years. Localization of ambysex sets the stage for gene identification and provides important tools for studying the effect of sex in laboratory and natural populations of this model amphibian system.

Keywords: Ambystoma, sex chromosome, sex determination, evolution, linkage map

INTRODUCTION

Distinct sexual phenotypes (e.g. male and female) are one of the most widespread forms of segregating phenotypic variation among vertebrates, and possibly all eukaryotes. Although mechanisms underlying vertebrate sex determination remain largely unknown, the available evidence suggests incredible diversity among and within each of the major groups. Sex determination in fishes ranges from Mendelian to polygenic, but in some cases, sex is entirely determined by environmental factors (Baroiller et al, 1999; Delvin and Nagahama, 2002; Mank et al, 2006). Environmental sex determination and sex chromosomes are distributed throughout reptilian phylogeny, suggesting independent evolutionary losses and gains, but conserved mechanisms are known for crocodilians (temperature) and birds (chromosomal sex determination) (Olmo, 1990; Ewert and Nelson, 1991; Pieau et al, 1999; Shine, 1999; Nanda et al, 2000; Nanda and Schmid, 2002). Of all the major vertebrate groups, sex determination is perhaps the most conserved among placental mammals, however even within this group there are a few interesting exceptions to the SRY gene rule (Sinclair et al, 1990; Just et al, 1995; Soullier et al, 1998; Pask and Graves, 1999). Given the amazing diversity in sex-determining mechanisms that are observed among vertebrates, it is expected that studies of additional groups will not only reveal new diversity, but will also elucidate conservative aspects of sex-determining and sex-differentiating pathways that characterized the ancestral vertebrate condition.

The vast majority of, if not all, amphibian species are thought to exhibit genetic modes of sex determination, however several evolutionary transitions between ZW and XY type sex-determining mechanisms (heterogametic females or males respectively) may have occurred (Hillis and Green, 1990; Schmid et al, 1991; Hayes, 1998; Wallace et al, 1999; Ogata et al, 2003; Ezaz et al, 2006). Under chromosomal sex determination, sexual differentiation depends upon the inheritance of a homologous (ZZ or XX) or heterologous (ZW or XY) pair of sex chromosomes. Alternate modes of sexual differentiation are determined by presence or absence of one or more loci between sex chromosomes, or by gene dosage. In either case, alternate sexual phenotypes (male and female) are expected to segregate as simple Mendelian traits, with a resulting 1:1 sex ratio among siblings of a large cross. While results consistent with a simple Mendelian mode of inheritance have been observed in the few amphibian species examined to date, non-Mendelian segregation of sexual phenotypes has also been observed (Pleurodeles waltl: Collenot et al, 1994; Rana and Hyla spp: Richards and Nance, 1978). These studies suggest that sex determination in some amphibians may depend upon more than a single, segregating genetic factor.

Salamanders of the genus Ambystoma are important amphibian models for studying development, ecology, and evolution, and with the recent development of a complete genetic map for Ambystoma the prospects of understanding the genetic basis of biologically important trait variation has become a reality (Voss and Smith, 2005). A number of developmental and cytogenetic experiments have established that sex is specified by a ZW type mechanism of chromosomal sex determination in Ambystoma mexicanum (Humphrey, 1945; Lindsley et al, 1956; Humphrey, 1957; Brunst and Hacshuka, 1963; Armstrong, 1984; Cuny and Malacinski, 1985) and possibly A. tigrinum tigrinum (Cuny and Malacinski, 1985) and members of the A. jeffersonianum species complex (Sessions, 1982). In addition, sex ratios suggest a single gene basis for sex determination in the laboratory strain of A. mexicanum (Humphrey, 1945; Lindsley et al., 1956; Humphrey, 1957; Armstrong, 1984). However, this hypothesis has not been tested with molecular markers and no sex determining genes have been mapped.

In this study, we revaluate the hypothesis that sex segregates in a 1:1 ratio when crossing tiger salamander species complex members (sensu Shaffer, 1984). We report segregation ratios of males and females that are largely consistent with the presence of a single sex-determining factor in the previously described WILD2 (Voss and Smith, 2005) backcross mapping family (wild collected A. mexicanum/A. t. tigrinum X wild collected A. mexicanum) as well as a new “wild” A. mexicanum X “lab” A. mexicanum F2 intercross (MEX1). To localize the major sex-determining factor to the Ambystoma genetic map, the WILD2 cross was genotyped for 156 previously developed markers (Smith et al, 2005). The analysis identified a single nucleotide polymorphism (E24C3, Linkage Group 5) with alleles that associate with male and female phenotypes. Two additional molecular markers were then developed to track segregation of E24C3 alleles within the MEX1 cross. As was observed for the WILD2 cross, segregating genotypes for E24C3 were strongly associated with segregating sex phenotypes in MEX1. Although we note a slight female bias in some crosses, our results validate the existence of a single Mendelian locus (ambysex) that acts as a primary sex-determining factor in A. mexicanum. We also note that patterns of recombination between the mapping panels suggest little differentiation of Z and W sex chromosomes, thus implying a recent origin for this sex determining system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic Strains and Crosses

Two crosses were used in this study: WILD2 and MEX1. The cross WILD2 was generated by backcrossing female F1 hybrids between A. mexicanum and A. t. tigrinum to male A. mexicanum to generate nine closely related families (Table 1). See Voss and Smith (2005) for a detailed description of the crossing design and rearing conditions that were used to generate WILD2. Two strains of A. mexicanum were used to generate the MEX1 cross. A female from the laboratory strain of A. mexicanum that is maintained by the Ambystoma Genetic Stock Center (http://www.ambystoma.org/AGSC/) was crossed to a strain that was more recently derived from the single natural population of A. mexicanum that occurs in Lake Xochimilco, Mexico D.F., Mexico. Two of the resulting F1 offspring were then mated to generate the MEX1 cross.

Table 1.

Segregation of sex among backcross progeny and corresponding G tests for goodness of fit to a 1:1 sex ratio.

| Cross | Male | Female | Proportion Test | df1 | G | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | (G) | ||||||

| 1 | 19 | 41 | 0.68 | 1 | 8.26 | 0.004 | |

| 2 | 17 | 23 | 0.58 | 1 | 0.90 | 0.342 | |

| 3 | 18 | 13 | 0.42 | 1 | 0.81 | 0.368 | |

| 4 | 21 | 24 | 0.53 | 1 | 0.20 | 0.655 | |

| 5 | 22 | 23 | 0.51 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.881 | |

| 6 | 26 | 36 | 0.58 | 1 | 1.62 | 0.203 | |

| 7 | 16 | 20 | 0.56 | 1 | 0.45 | 0.505 | |

| 8 | 13 | 13 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.000 | |

| 9 | 5 | 10 | 0.67 | 1 | 1.70 | 0.192 | |

| Total | 157 | 203 | 0.56 | Total | 9 | 13.96 | 0.124 |

| Pooled | 1 | 5.89 | 0.015 | ||||

| Heterogeneity | 8 | 8.06 | 0.427 | ||||

– Degrees of freedom.

Rearing conditions

At approximately 20 days post-fertilization, larvae were released from their eggs and placed individually in 5 oz paper cups of 20% Holtfretter’s solution (Asashima et al, 1989). Throughout the course of these experiments all individuals from each of the mapping panels were maintained in a single room within which the temperature fluctuated from 19–22°. Individuals were reared in separate containers and rotated within the room after water changes to reduce effects of spatial temperature variation. Larvae were fed freshly hatched Artemia twice daily for their first 30 days post-hatching. After day 20 their diet was supplemented with small (<1cm long) California black worms (Lumbriculus). During this time, individuals were provided with fresh water and cups after every third feeding. On day 30 larvae were transferred to 16 oz plastic bowls, after which they were fed exclusively California black worms and water was changed every third day. Finally, at 80 days post-fertilization, all individuals were transferred to 4 L plastic containers and were otherwise maintained under the same regime as the previous 50 days.

Phenotypic Scores

WILD2

The majority of WILD2 offspring were euthanized upon completion of metamorphosis or at day 350. At this time, individuals were dissected, tissue samples (liver and/or blood) were harvested for DNA isolation, and gonads were examined to identify each individual’s sex phenotype. Individuals with gonads consisting of a membrane surrounding translucent (immature ova), or opaque/pigmented (more mature ova) spheres were classified as females. Individuals with gonads appearing as opaque-ovoid (immature testes) or lobed (more mature testes) structures were classified as males. Individuals metamorphosing early in the experiment often could not be unequivocally assigned to either sex (Humphrey, 1929; Gilbert, 1936); these individuals were classified as immatures. Gonads of immatures appeared as a thin strip of tissue (undifferentiated gonadal primordia or early stages of differentiation) adjacent to the abdominal fat bodies. A few individuals were not euthanized and are currently being maintained for use in future studies. For these individuals, sex was scored after the development of secondary sexual characteristics. In particular, the cloacal opening of male ambystomatids is much longer than that of females and male cloacal lips are several times larger than those of females. Dissected animals invariably corroborated cloacal sex scores. Sex was identified for a total of 360 WILD2 individuals within this study.

MEX1

Sex phenotypes for the MEX1 cross were scored in the same manner as described for the WILD2, except that all animals from this cross remained paedomorphic and all individuals were scored at day 310 post fertilization. At this age, all animals had completed gonadal differentiation and sex phenotypes were unequivocally identified for all 93 individuals.

Genotyping

Based on previous studies, which suggested that the sex-determining gene of ambystomatids resides on one of the smaller chromosomes (A. mexicanum and A. t. tigrinum – Brunst and Haschuka, 1963; Cuny and Malacinski, 1985; A. jeffersonianum species complex – Sessions, 1982), an initial screen for the sex-determining factor was targeted to the five smallest linkage groups, LG10 – LG14 (Smith et al, 2005). In this screen, 54–161 individuals of known sex phenotype (>195 days old) were genotyped for 23 molecular markers that were broadly scattered across these linkage groups (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). A second screen targeted the remaining 9 linkage groups of the map. This screen used an initial panel of 24 paedomorphs and late-metamorphosing individuals (12 males and 12 females) from WILD2.3 and targeted 124 previously described genetic markers (Smith et al, 2005) that were spaced at roughly 30 cM intervals (Supplementary Tables 1 – 3). Based on analyses of genotypes from the initial screens, E24C3 and E26C11 were also genotyped for a larger subset of the WILD2 panel (N=375 for E24C3; N = 74 for E26C11).

Three novel genetic markers were developed for this study, using previously described methods (Smith et al, 2005). One of these probes (E26C11_329_3.1_A/G –GGGTTCTCTCAATGAACTGTATGTTGATTG) was designed to genotype the marker E26C11 in WILD2. Two additional fluorescence polarization probes were developed to genotype the E24C3 marker fragment in the MEX1 cross (E24C3_79_3.1_G/A –CTGTGGTGTATTCGAACATGTCGC, and E24C3_318_3.1_G/A –AGGGCCTTCACATATTTTTCTGCAAAATAT). Polymorphisms segregating in the WILD1 cross were identified by sequencing E24C3 PCR amplicons from the P1 and F2 founders. These markers were genotyped using standard primer extension and fluorescence polarization protocols (Perkin Elmer, AcycloPrime -FP chemistry and Wallac, Victor3 plate reader) (e.g. Chen et al, 1999; Hsu et al, 2001; Gardiner and Jack, 2002).

Statistical Analyses: Segregation of sex

Sex ratios within crosses were examined for fit to a 1:1 ratio expected under single locus sex determination, using G tests (Sokal and Rohlf, 1995). Because WILD2 consisted of several crosses, tests for homogeneity (G heterogeneity (h)) among crosses and fit to a 1:1 sex ratio in the data pooled across crosses (Gpooled (p)), were performed in addition to tests for fit to a 1:1 sex ratio for individual crosses (G) (Sokal and Rohlf, 1995). Lack of fit to a 1:1 sex ratio would suggest that genetic factors, in addition to a single locus, might contribute to sex determination in Ambystoma.

Association analyses

Likelihood ratio statistics (LRS) for association of phenotypic variation with genotypic inheritance were estimated using the interval mapping and marker regression functions of MapManagerQTXb19 (Meer et al, 2004). Significance thresholds for interval mapping were obtained through 10,000 permutations of trait values among backcross progeny.

RESULTS

Segregation of Sex

WILD2

The sex of 360 WILD2 individuals was identified by gonadal and/or cloacal morphology. All remaining larvae (N = 137) were scored immature. The ratios of males to females from 8 of 9 crosses were consistent with a 1:1 ratio expected under the hypothesis that a single locus specifies sex in Ambystoma (Table 1). A significantly female-biased sex ratio was observed in Cross 1 (G = 8.26, DF = 1, P = 0.004) and non-significant female bias was observed in 5 other crosses. Sex ratios among crosses were not significantly heterogenous (Gh= 8.06, DF = 8, P = 0.427); therefore, data for sex were pooled and tested for fit to 1:1. Pooling of female-biased sex ratios among individual crosses revealed an overall female-biased sex ratio (203 females and 157 males) that deviated significantly from 1:1 (Gp= 8.06, DF = 1, P = 0.015, N = 360).

MEX1

Sex phenotypes were obtained for a total of 93 individuals from the MEX1 cross: 46 males and 47 females. As was observed for the majority of WILD2 crosses, the sex ratio in MEX1 is consistent with a 1:1 ratio expected under the hypothesis that a single locus specifies sex in Ambystoma (G = 0.01, DF = 1, P = 0.917, N = 93).

Segregation of Molecular Markers in WILD2

A total of 159 markers were genotyped for the WILD 2 cross. The distribution of these markers across the linkage map (Smith et al, 2005) indicates that 92% of map is within 30cM of at least one molecular marker and 73% of the map is within 15cM. Most of the regions that were not covered by this screen are represented only by anonymous (AFLP) markers. Segregation ratios of molecular markers deviated from 1:1 less often than expected based on the distribution of values for the χ2 test for 1:1 segregation (Supplementary Figure 1). A similar pattern of deviation from χ2, towards unity, was observed in a previous study that mapped the same markers using independently generated crosses (Smith et al, 2005). These results show that the segregation of molecular markers in A. mexicanum x A. t. tigrinum interspecific crosses is not distorted.

Linkage Analysis of Sex in WILD2

Genetic screens for sex-associated regions of the Ambystoma genome identified a single marker (E24C3) that was completely associated with segregation of sex phenotypes in the subpopulation of 24 WILD2 offspring that were used for the initial genome scan. This marker is the most terminal gene/EST based marker at one tip of LG5. The WILD2 mapping family was generated using a backcross mating design, therefore individuals segregated two genotypes for the E24C3 marker, E24C3G/G (homozygous for the A. mexicanum genotype) and E24C3 G/A (A. mexicanum/A. t. tigrinum heterozygotes) (Table 2). The male phenotype was associated with inheritance of the heterozygous E24C3 G/A genotypes, whereas the female phenotype was associated with inheritance of the homozygous E24C3G/G genotype. The pattern of segregation of E24C3G/G vs. E24C3 G/A genotypes is consistent with the previously demonstrated ZW (heterogametic female) sex-determining mechanism of A. mexicanum (Humphrey, 1945; Lindsley, 1956; Humphrey, 1957; Armstrong, 1984), given that the P1 A. mexicanum and the F1 hybrid were females (respectively, ZA. mexicanum (A.mex)/W A.mex and ZA. t. tigrinum (A.t.t)/W A.mex) and the P1 A. t. tigrinum and P2 A. mexicanum were males (respectively, Z A.t.t/Z A.t.t and Z A.mex/Z A.mex). Backcross progeny can therefore only inherit two genotypes (Z A.mex/Z A.t.t: male) or (Z A.mex/W A.mex: female). According to this model, second generation females inherited a W A.mex locus, and frequently, a linked E24C3G (A. mexicanum) allele from their F1 mother.

Table 2.

Segregation of E24C3 genotypes and sex phenotypes in a subset of the WILD2 cross.

| Sex | E24C3G/G | E24C3G/A |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 160 | 23 |

| Male | 11 | 117 |

| Early-Metamorphosing | 79 | 75 |

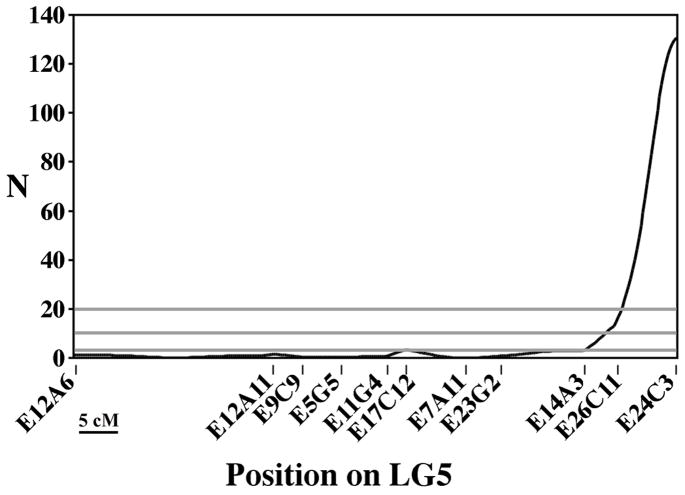

To further resolve the position of the sex-associated region on LG5, larger panels of late-metamorphosing individuals (at least 175 days old at metamorphosis) were genotyped for the E24C3 marker (N = 221) and the flanking marker E26C11 (N = 74). Again, segregating genotypes for these markers were strongly associated with segregation of the sexes (E24C3: LRS = 220, P < 1E-5; E26C11: LRS = 13.8, P = 2E-4) (Table 2 and 3). Based on these genotypes, the most likely position for a single sex determining locus is 10.6 cM distal to the position of E24C3 on LG5 (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Segregation of E26C11 genotypes and sex phenotypes in a subset of the WILD2 cross.

| Sex | E26C11A/A | E26C11A/G |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 24 | 14 |

| Male | 8 | 28 |

Figure 1. Plot of Likelihood Ratio Statistics (LRS) for association between segregation of sex phenotypes and marker genotypes on LG5 (WILD2).

Horizontal lines represent (from bottom to top) linkage group-wide LRS thresholds for suggestive (37th percentile), significant (95th percentile), and highly significant (99.9th percentile) associations (Lander and Kruglyak, 1995) estimated using MapMaker QTXb19 and 24 –74 informative progeny.

With sex locus markers in hand, we determined E24C3 genotypes for the 154 early-metamorphosing individuals (<175 days old at metamorphosis), that either possessed morphologically undifferentiated gonads or were in early stages of morphological differentiation. Among these animals there were 79 E24C3G/G homozygotes (presumptive females) and 75 E24C3G/A heterozygotes (presumptive males) (Table 2). This sex ratio is slightly female biased, but not different from 1:1 (χ2 = 0.1, P = 0.75, DF = 1). Thus, these previously missing phenotypes are consistent with the observed pattern of female-biased sex ratios in WILD2. We also note no significant correlation was observed between age at metamorphosis and E24C3 genotype when all 338 metamorphic individuals were considered (T = 1.14, P = 0.26, DF = 336). Thus, there is no evidence of an effect of sex on metamorphic timing under our rearing conditions.

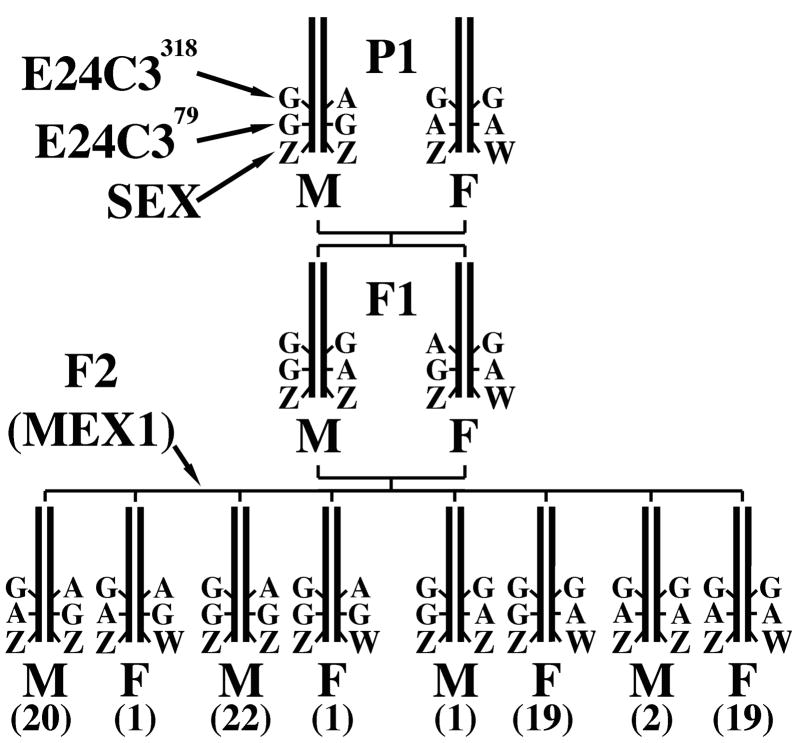

Association Between E24C3 and Sex in MEX1

We extended the previous mapping results to the intraspecific level by testing the hypothesis that E24C3 is linked to the sex-determining factor in the species A. mexicanum. To test this hypothesis, 85 individuals from the cross MEX1 were genotyped for two SNPs that segregated within the E24C3 marker fragment. Genotypes for E24C3 were strongly associated with segregation of male and female phenotypes in the MEX1 panel (Figure 2) (for E24C3318 – LRS = 20.3, P = 1E−5, N = 85; for E24C379 – LRS = 25.0, P < 1E−5, N = 85). As was the case in the WILD2 mapping family, the pattern of association in the MEX1 cross is consistent with the previously demonstrated ZW sex-determining mechanism of A. mexicanum (Humphrey, 1945; Lindsley, 1956; Humphrey, 1957; Armstrong, 1984) (Figure 2). Using MEX1, the distance between E24C3 and the sex-determining factor is estimated at approximately 5.9 cM. This is similar to the estimate obtained using the WILD2 panel.

Figure 2. Diagram of the crossing design that was used to generate the MEX1 cross and segregation of E24C3 marker genotypes and Z/W alleles of the ambysex locus in this crossing design.

The numbers of individuals that inherited each multilocus genotype are in parentheses. M = male, F = female. E24C3 SNP markers are on the same PCR fragment.

DISCUSSION

Localization of a major sex-determining factor of A. mexicanum

Localization and inheritance of a single sex-determining factor in A. mexicanum is consistent with results from previous genetic studies of sex-determination. Previous studies firmly established a ZW type sex-determining mechanism for A. mexicanum (Humphrey, 1945; Lindsley et al, 1956; Humphrey, 1957; Armstrong, 1984) and linkage analyses showed that the sex-determining factor is not linked to a centromere (Lindsley et al, 1956; Armstrong, 1984). The patterns of association between E24C3 and sex are consistent with segregation of a female specific “W” locus and the terminal location of ambysex on LG 5 indicates it is very distant from the centromere, as all of the larger chromosomes are metacentric in Ambystoma (Callan, 1966). The sex-linked region of LG 5 corresponds to human chromosome 2 (Smith and Voss, 2006). We have not yet identified a definitive ortholog for E24C3.

It is curious that ambysex maps to one of the larger linkage groups in the genome. The estimated length of the smallest linkage group of the Ambystoma map (LG14 = 125.5 cM) is considerably smaller than LG5 (292 cM). Prior to our study, the data were equivocal with regards to the location of the sex-determining locus and whether this locus was associated with dimorphic sex chromosomes. Two cytogenetic studies previously reported subtle heteromorphisms of the smallest chromosome pair that were consistent with ZW segregation (Haschuka and Brunst, 1965; Cuny and Malacinski, 1985). However, other analyses of tiger salamander (A. mexicanum and A. t. tigrinum) karyotypes do not report sex-specific heteromorphisms (Parmenter, 1919; Dearing, 1934), and Callan (1966) disputed their existence. Our results support the idea that the sex-determining locus is on one of the larger chromosome pairs. By logical extension, this suggests that the Z and W chromosomes of A. mexicanum are not morphologically differentiated to any appreciable degree.

Recombination rates in the ambysex-linked region imply a recent origin for ambysex

Previously published linkage analyses were based on recombination that occurred in the testes of male (presumably ZZ) F1 hybrids between A. mexicanum and A. t. tigrinum (Voss, 1995; Smith et al, 2005). Estimates of linkage distance in WILD2 are based on female (ZW) recombination, and estimates of linkage distance in MEX1 are based on recombination in both sexes. Divergence of tiger salamander Z and W chromosomes should tend to reduce recombinational distances in female meiosis relative to male meiosis. The recombinational distance between E24C3 and a Mendelian ambysex locus in WILD2 is similar to the frequency of recombination between E24C3 and ambysex in the male and female F1s that founded MEX1 (Table 2, Figure 2). Moreover, the estimated ZW recombinational distance between E24C3 and E26C11 was 30.2 cM in WILD2, higher than the estimated ZZ recombinational distance (13.6 cM) for these same loci in AxTg (Smith et al, 2005). In the few other cases where recombination frequencies have been characterized for young (~10 million year old) sex chromosomes (e.g. medaka: Kondo et al, 2004; stickleback: Peichel et al, 2005; and papaya: Lui et al, 2004; Ma et al, 2004) the frequency of recombination in the 30–100 cM adjacent to the sex-determining factor is substantially reduced within the heterogametic sex, relative to the homogametic sex. Given the lack of evidence for differences in recombination frequency in this study, the recent radiation of the tiger salamander species complex (Shaffer and McKnight 1996), and the lack of convincing cytogenetic evidence for structurally differentiated sex chromosomes in the tiger salamander lineage, it stands to reason that the ambysex locus arose quite recently, perhaps within the last 5–10 million years.

Female bias in WILD2

Although the evidence is strong for the presence of a major sex-determining locus in WILD2, the observation of slight, but consistent, female bias indicates that additional factors may have also influenced segregation of sex in this mapping family. It is interesting to note that sex bias in WILD2 is in the opposite direction of biases that might be expected to arise from hybrid incompatibilities that depend on the hemizygous inheritance of a differentiated Z chromosome (Haldane’s Rule: Presgraves and Orr, 1998; Turelli and Orr, 2000). It is also notable that in WILD2 and MEX1, the number of females with presumptively recombinant genotypes (N = 23 E24C3 G/A females in WILD2) is greater than the number of presumptively recombinant males (N = 11 E24C3 G/G males in WILD2). The greater number of females might reflect the presence of additional genetic factors that cause ZZ individuals to develop as females, or an increased mortality of male recombinants during pre-hatching stages. Identification of markers that are more tightly linked to the sex-determining locus, or the sex-determining locus itself, should ultimately permit recombinant individuals to be differentiated from potentially sex-reversed individuals.

It is also possible, though perhaps less likely, that female-biased sex ratios were generated as a result of environmental conditions under which WILD2 offspring were reared. Although all WILD2 individuals experienced very similar environmental conditions, it is formally possible that these conditions increased the probability that individuals developed as females, irrespective of genotype. Temperature is known to affect sex ratio in some salamanders (reviewed by Wallace et al, 1999), but only at extreme levels that are not encountered during normal laboratory culture. Perhaps more importantly, the only study to test for environmental effects on sex ratios in Ambystoma found no deviation from a 1:1 sex ratio in A. tigrinum or A. maculatum reared at 13 or 22° (Gilbert, 1936), which encompasses the range of temperature variation within this study. Thus, it seems unlikely that the observed slight female bias was caused by rearing temperature in WILD2 crosses. With validated markers for sex, it is now possible to systematically test for environmental or effects on sex determination in A. mexicanum and possibly other members of the tiger salamander species complex.

Sex and the biology of ambystomatid salamanders

Results from WILD2 indicate that the genetic sex-determining mechanism of A. mexicanum functions within the genomes of F1 hybrids between A. mexicanum and A. t. tigrinum and their backcross offspring. This suggests that the genetic sex determining mechanism of A. mexicanum is likely to be conserved in the many closely related species that comprise the tiger salamander species complex. Tiger salamanders are important models for studying development (e.g. Monaghan et al. 2007; Page et al. 2008; Zhang et al, 2007), ecology (e.g. Trenham and Shaffer, 2005; Fitzpatrick and Shaffer, 2004; Brunner JL et al, 2005), and evolution (e.g. Voss and Smith, 2005; Robertson et al, 2006; Weisrock et al, 2006). Thus, the sex-markers described in this study will open many new avenues of research and allow better management of laboratory populations. For example, it should be straightforward to develop orthologous markers for other closely related tiger salamanders and determine whether sex-determining mechanisms are conserved or different. Studies of more distantly related taxa are also needed (e.g. Ogata et al, 2003; Ezaz et al, 2006) to fully characterize the evolution and diversity of sex-determining mechanisms in amphibians.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information is available at Heredity’s website

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants R24-RR016344 and P20-RR016741 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or NIH. The National Science Foundation provided support via IBN-0242833. The Spinal Cord and Brain Injury Research Center at UK and the NSF-supported Ambystoma Genetic Stock Center (DBI-0443496) provided resources and facilities. We also thank K. Peichel for providing a critical review of the manuscript prior to submission.

LITERATURE CITED

- Armstrong JB. Genetic Mapping in the Mexican axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum. Can J Genet Cytol. 1984;26:1–6. doi: 10.1139/g84-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asashima M, Malacinski GM, Smith SC. Surgical manipulation of embryos. In: Armstrong JB, Malacinski GM, editors. Developmental Biology of the Axolotl. Oxford Univ. Press; New York: 1989. pp. 252–263. [Google Scholar]

- Baroiller JF, Guigen Y, Fostier A. Endocrine and environmental aspects of sex differentiation in fish. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:910–931. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner JL, Richards K, Collins JP. Dose and host characteristics influence virulence of ranavirus infections. Oecologia. 2005;144:399–406. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunst VV, Hauschka TS. Length measurements of the diploid karyotype of the Mexican axolotl (Siredon mexicanum) with reference to a possible sex difference. Proc XVIth int Congr Zool, Wash. 1963;2:274. [Google Scholar]

- Callan HG. Chromosomes and nucleoli of the axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum. J Cell Sci. 1966;1:85–108. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Levine L, Kwok P-Y. Fluorescence polarization in homogenous nucleic acid analysis. Genome Res. 1999;9:492–498. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collenot A, Durand D, Lauther M, Dorazi R, Lacroix JC, Dournon C. Spontaneous sex reversal in Pleurodeles waltl (urodele amphibia): analysis of its inheritance. Genet Res. 1994;64:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cuny R, Malacinski GM. Banding differences between tiger salamander and axolotl chromosomes. Can J Genet Cytol. 1985;27:510–514. doi: 10.1139/g85-076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing WH., Jr The maternal continuity an individuality of the somatic chromosomes of Ambystoma tigrinum, with special reference to the nucleolus as a chromosomal component. J Morph. 1934;56:157–179. [Google Scholar]

- Delvin RH, Nagahama Y. Sex determination and sex differentiation in fish: an overview of genetic, physiological, and environmental influences. Aquaculture. 2002;208:191–364. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert MA, Nelson CE. Sex determination in turtles: diverse patterns and some possible adaptive values. Copeia. 1991;1:50–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ezaz T, Stiglec R, Veyrunes F, Graves JAM. Relationships between vertebrate ZW and XY sex chromosome systems. Curr Biol. 2006;16:R736–R743. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick BM, Shaffer HB. Environment-dependent admixture dynamics in a tiger salamander hybrid zone. Evolution. 2004;58:1282–1293. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner AF, Jack WE. Acyclic and dideoxy terminator preferences denote divergent sugar by archaeon detection. BioTechniques. 2002;31:560–570. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.2.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert WM. Amphisexuality and sex differentiation in Ambystoma. State University of Iowa; 1936. Unpublished Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Hauschuka TS, Brunst VV. Sexual dimorphism in the nucleolar autosome of the axolotl (Sirenodon mexicanum) Hereditas. 1965;52:345–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1965.tb01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes TB. Sex determination and primary sex differentiation in amphibians: Genetic and developmental mechanisms. J Exp Zoo. 1998;281:373–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis DM, Green DM. Evolutionary changes of heterogametic sex in the phylogenetic history of amphibians. J Evol Biol. 1990;3:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu TM, Chen X, Duan S, Miller RD, Kwok P-Y. Universal SNP genotyping assay with fluorescence polarization detection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;30:605–613. doi: 10.2144/01313rr01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey RR. Studies on sex reversal in Ambystoma: bisexuality and sex reversal in larval males uninfluenced by ovarian hormones. Anat Rec. 1929;42:119–155. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey RR. Sex determination in the Ambystomatid salamanders: a study of the progeny of females experimentally converted into males. Am J Anat. 1945;76:33–66. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey RR. Male homogamety in the Mexican axolotl: a study of the progeny obtained when germ cells of a genetic male are incorporated into the developing ovary. J Exp Zoo. 1957;134:91–101. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401340105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just W, Rau W, Vogel W, Akhverdian M, Fredga K, Graves JAM, et al. Absence of SRY in species of the vole Ellobius. Nature Genet. 1995;11:117–118. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M, Nanda I, Hornung U, Schmid M, Schartl M. Evolutionary origin of the medaka Y chromosome. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1664–1669. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley DL, Fankhauser G, Humphrey RR. Mapping centromeres in the axolotl. Genetics. 1956;41:58–64. doi: 10.1093/genetics/41.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZY, Moore PH, Ma H, Ackerman CM, Ragiba M, Yu Q, et al. A primitive Y chromosome in papaya marks incipient sex chromosome evolution. Nature. 2004;427:348–352. doi: 10.1038/nature02228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Moore PH, Liu Z, Kim MS, Yu Q, Fitch MMM, et al. High-density linkage mapping revealed suppression of recombination at the sex determination locus in papaya. Genetics. 2004;166:419–436. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.1.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mank JE, Promislow DEL, Avise JC. Evolution of alternative sex-determining mechanisms in teleost fishes. Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 2006;87:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Meer JM, Cudmore RH, Jr, Manly KF. MapManager QTX. 2004. http://ww.mapmanager.org/mmQTX.html.

- Monaghan JR, Walker JA, Beachy CK, Voss SR. Microarray analysis of early gene expression during natural spinal cord regeneration in the salamander Ambystoma mexicanum. J Neurochem. 2007;101:27–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda I, Schmid M. Conservation of avian Z chromosomes as revealed by comparative mapping of the Z-linked aldolase B gene. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2002;96:176–178. doi: 10.1159/000063019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda I, Zend-Ajusch E, Shan Z, Grutzner F, Schartl M, Burt DW, et al. Conserved synteny between the chicken Z sex chromosome and human chromosome 9 includes the male regulatory gene DMRT1: a comparative (re)view on avian sex determination. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2000;89:67–78. doi: 10.1159/000015567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata M, Ohtani H, Igarashi T, Hasegawa Y, Ichikawa Y, Miura I. Change of the heterogametic sex from male to female in the frog. Genetics. 2003;164:613–620. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.2.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmo E. Cytogenetics of Reptiles and Amphibians. Birkhauser Verlag; Basel, Switzerland: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Page RB, Voss SR, Samuels AK, Smith JJ, Putta S, Beachy CK. Effect of thyroid hormone concentration on the transcriptional response underlying induced metamorphosis in the Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma) BMC Genomics. 2008;9:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmenter CL. Chromosome number and pairs in the somatic mitoses of Ambystoma tigrinum. J Morph. 1919;33:169–242. [Google Scholar]

- Pask AJ, Graves JAM. Sex chromosomes and sex-determining genes: insights from marsupials and monotremes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:864–875. doi: 10.1007/s000180050340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peichel CL, Ross JA, Matson CK, Dickson M, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, et al. The master sex-determination locus in threespine sticklebacks is on a nascent Y chromosome. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1416–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves DC, Orr HA. Haldane’s rule in taxa lacking a hemizygous X. Science. 1998;282:952–954. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieau C, Dorizzi M, Richard-Mercier N. Temperature dependant sex determination and gonadal differentiation in reptiles. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:887–900. doi: 10.1007/s000180050342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards CM, Nace GW. Cytogenetic and hormonal sex reversal used in testes of the XX-XY hypothesis of sex determination in Rana pipiens. Growth. 1978;42:319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AV, Ramsden C, Niedzwiecki J, Fu ZJ, Bogart JP. An unexpected recent ancestor of unisexual Ambystoma. Mol Ecol. 2006;15:3339–3351. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Nanda I, Steinlein C, Kausch K, Epplen JT, Haaf T. Sex determining mechanisms and sex chromosomes in amphibia. In: Green DM, Sessions SK, editors. Amphibian Cytogenetics and Evolution. Academic Press; New York: 1991. pp. 393–430. [Google Scholar]

- Sessions SK. Cytogenetics of diploid and triploid salamanders of the Ambystoma jeffersonianum complex. Chromosoma. 1982;77:599–621. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer HB. Evolution in a paedomorphic lineage. 1. An electrophoretic analysis of the Mexican ambystomatid salamanders. Evolution. 1984;38:1194–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1984.tb05643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer HB, McKnight ML. The polytypic species revisited: Genetic differentiation and molecular phylogenetics of the tiger salamander, Ambystoma tigrinum (Amphibia: Caudata) complex. Evolution. 1996;50:417–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb04503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shine R. Why is sex determined by nest temperature in so many reptiles? Trends Ecol Evol. 1999;14:186–189. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01575-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair A, Berta HP, Palmer MS, Hawknis JR, Griffiths BL, Smith MJ, et al. A gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif. Nature. 1990;346:240–244. doi: 10.1038/346240a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JJ, Voss SR. Gene order data from a model amphibian (Ambystoma): new perspectives on vertebrate genome structure and evolution. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:219. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JJ, Kump DK, Walker JA, Parichy DM, Voss SR. A comprehensive expressed sequence tag linkage map for tiger salamander and Mexican axolotl: enabling gene mapping and comparative genomics in Ambystoma. Genetics. 2005;171:1161–1171. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.046433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal FJ, Rohlf RR. Biometry: the principles and practice of statistics in biological research. 3. W.H. Freeman and Company; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Soullier S, Hanni C, Catzeflis F, Berta P, Laudet V. Male sex. determination in the spiny rat Tokudaia osimensis (Rodentia: Muridae) is not Sry dependent. Mamm Genome. 1998;9:590–592. doi: 10.1007/s003359900823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenham PC, Shaffer HB. Amphibian upland habitat use and its consequences for population viability. Ecol Appl. 2005;15:1158–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Turelli M, Orr HA. Dominance, epistasis and the genetics of postzygotic isolation. Genetics. 2000;154:1663–1679. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.4.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss SR. Genetic basis of paedomorphosis in the axolotl Ambystoma mexicanum: a test of the single gene hypothesis. J Hered. 1995;86:441–447. [Google Scholar]

- Voss SR, Smith JJ. Evolution of salamander life cycles: A major effect QTL contributes to discreet and continuous variation for metamorphic timing. Genetics. 2005;170:275–281. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.038273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace HG, Badawy MI, Wallace BM. Amphibian sex determination and sex reversal. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:901–909. doi: 10.1007/s000180050343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisrock DW, Shaffer HB, Storz BL, Storz SR, Voss SR. Multiple nuclear gene sequences identify phylogenetic species boundaries in the rapidly radiating clade of Mexican ambystomatid salamanders. Mol Ecol. 2006;15:2489–2503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Pietras KM, Sferrazza GF, Jia P, Athauda G, Rveda-de-leon E, et al. Molecular and immunohistochemical analyses of cardiac troponin T during cardiac development in the Mexican axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100:1–15. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information is available at Heredity’s website