Abstract

The buccal space is an anatomical compartment lying anterior to the masticator space and lateral to the buccinator muscle. Since the major purpose of imaging is to define the likely anatomic origin and also the extent of a given lesion, thorough knowledge of the normal anatomy of the buccal space is essential, and this knowledge can aid the physician in narrowing down the list of possible maladies on the differential diagnosis. We illustrate here in this paper the important anatomic landmarks and typical pathologic conditions of the buccal space such as the developmental lesions and the neoplastic lesions. Knowledge of the expected pathologic conditions is useful for the radiologist when interpreting facial CT and MR images.

Keywords: Magnatic resonance (CT), Computed tomography (MR), Buccal space, Face

The buccal space is located lateral to the buccinator muscle and deep to the zygomaticus major muscle (1). This space is filled with adipose tissue (termed the buccal fat pad), the parotid duct, the facial artery and vein, lymphatic channels, the minor salivary glands and the branches of the facial and mandibular nerves. Patients suffering with the buccal space lesions usually present with a cheek mass or facial swelling. Although a variety of lesions are known to occur within this space, their radiological features have not been well covered in the literature. Since the possible diagnosis of these masses is effectively limited to a narrow range of diseases if their compartment of origin is known, it is important to know the normal anatomy and common diseases of the buccal space. In this article, we illustrate the important anatomic landmarks and typical pathologic conditions of the buccal space.

NORMAL ANATOMY

The buccal space's (Fig. 1) anatomical boundaries are the buccinator muscle medially, the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia and the muscles of facial expression laterally and anteriorly, and the masseter muscle, mandible, lateral and medial pterygoid muscles and the parotid gland posteriorly (1). The buccinator muscle originates from the alveolar processes of the maxilla and the mandible, and it inserts into the pterygomandibular raphe. The buccal space frequently communicates posteriorly with the masticator space because the parotidomasseteric fascia is sometimes incomplete along its medial course where it joins the buccopharyngeal fascia. There is no true superior or inferior boundary of the buccal space.

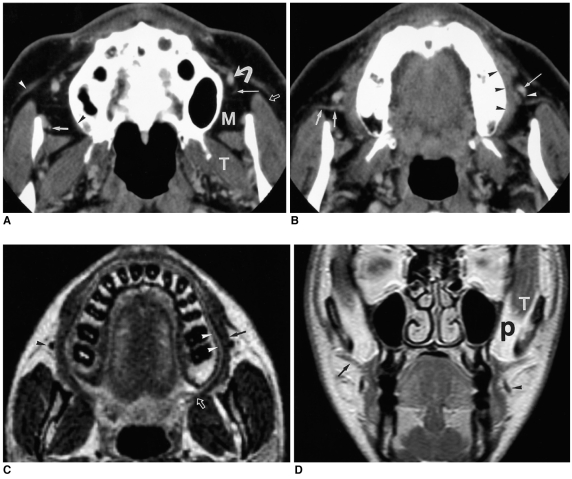

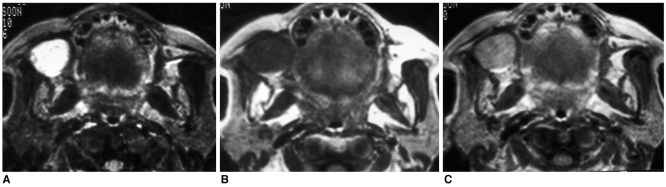

Fig. 1.

The normal anatomy of the buccal space.

A. A transverse enhanced CT scan at the level of the upper buccal space shows the lateral projection (open arrow) of buccal fat lateral to the masseter muscle and the medial projection (M) of buccal fat between the masseter muscle and the maxilla. The posterior extent of the medial buccal fat pad is limited by the lateral pterygoid muscle (T) and the overlying fascia. The origin of the buccinator muscle is seen on the right side (black arrowhead). The facial vein (curved arrow) is seen located within the buccal space. The facial artery (long arrow), buccal artery (short arrow), and zygomaticus muscle (white arrowhead) are noted.

B. A transverse enhanced CT scan at the level of the middle buccal space shows the parotid duct (short arrows) coursing through the buccal space. The angular portion of the facial vein (arrow) and facial artery (arrowhead) are located anterior to the duct. The buccinator muscle (black arrowheads) is also noted.

C. A transverse T2-weighted MR image at the level of the lower buccal space shows the buccinator muscle (arrow) having a low signal intensity and the submucosal fat pad (arrowheads) having a high signal intensity. The insertion of the buccinator muscle on the pterygomandibular raphe (open arrow) is also visible at this level. The facial vein (arrowhead) appears as a signal void.

D. A coronal enhanced T1-weighted MR image shows the parotid duct (arrow), facial vein (arrowhead), and buccinator muscle. The deep portion of the buccal fat pad (P) lies between the temporal muscle (T) and the maxillary sinus.

The greater part of the space is filled by adipose tissue that has been termed as the buccal fat pad. The buccal fat pad has four projections away from the more central body of adipose tissue. The lateral projection follows the parotid duct posteriorly to lie adjacent to the anterolateral portion of the superficial lobe of the parotid gland. The buccal fat pad extends medially between the mandible and maxillary sinus, and it frequently communicates with fat in the masticator space. The anterior portion of the buccal fat pad extends anterior to the parotid duct and the facial vein. The superior temporal extensions of the buccal fat are divided into the deep and superficial subdivisions with respect to the temporal muscle. The main duct of the parotid gland (Stenson's duct) courses in a transverse fashion through the buccal fat pad, and it pierces the buccinator muscle opposite the second maxillary molar. This parotid duct separates the buccal space into two equal-sized anterior and posterior compartments. The CT attenuation of the posterior compartment has been reported to be less than that of the fat in the anterior compartment and in the adjacent spaces (1).

The other contents include the parotid duct, the minor salivary glands, accessory parotid lobules, facial, and buccal arteries, facial vein, lymphatic channels and the branches of the facial and mandibular nerves. The facial vein is typically identified on cross-sectional images as being located along the lateral margin of the buccinator muscle, just anterior to Stenson's duct.

When tumor or infection is involved in the buccal space, the buccal space can serve as a conduit for spreading desease between the mouth and the parotid gland. The lack of fascial compartmentalization in the superior, inferior and posterior directions permits the spread of pathology both to and from the buccal space (2).

ABNORMALITIES

A variety of diseases are known to occur within the buccal space, including developmental lesions, infection and inflammation, neoplastic lesions and other miscellaneous conditions. Accessory parotid tissue, congenital fistula of the parotid duct, dermoid cyst and vascular lesions such as hemangioma and vascular malformation are common developmental lesions found in this location (2). The most common tumor of the buccal space are minor salivary gland tumors such as pleomorphic adenoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma (2-4). The other tumors are those originating from muscular, neural, connective and lymphatic tissues, and these include rhabdomyoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, neurofibroma, schwannoma, lipoma, liposarcoma, lymphoma, and metastatic lymphadenopathy. Various miscellaneous conditions would include Kimura disease and foreign body granulomas.

DEVELOPMENTAL LESIONS

Accessory Parotid Tissue

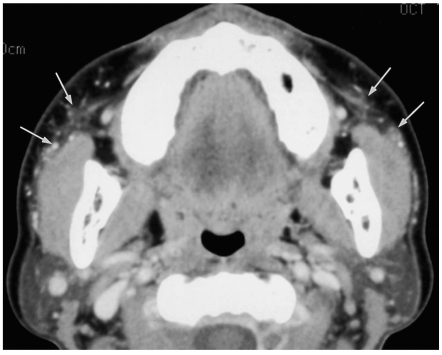

In approximately 20% of the population, accessory parotid tissue is present in the buccal space, and this is usually just anterior to the parotid gland hilum, overlying the anterior margin of the masseter muscle (2). Accessory parotid tissue (Fig. 2) is identified by CT more often than by using MR imaging (1). Accessory parotid tissue may be unilateral or bilateral and it is histologically and physiologically identical to the tissue in the main parotid gland.

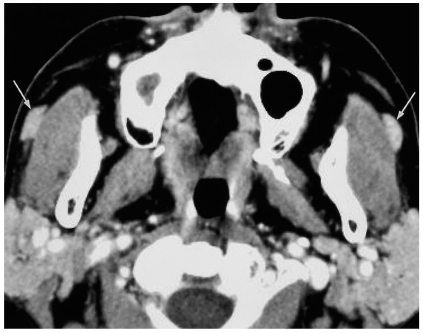

Fig. 2.

Bilateral accessory parotid tissues in a 59-year-old man.

A transverse enhanced CT scan shows the bilateral accessory parotid tissues (arrows), which have the same attenuation as the tissue in the main parotid gland.

Dermoid Cyst

Simple dermoid cysts typically appear as low-density, well-circumscribed, thin-walled unilocular cystic masses on CT (2). Compound dermoid cysts have a more variable appearance such as a fat-fluid level or as a fat globule, and they may have high signal intensity on T1-weighted images depending on their lipid content (2). When complicated by infection, their discrimination from abscess can be impossible (Fig. 3).

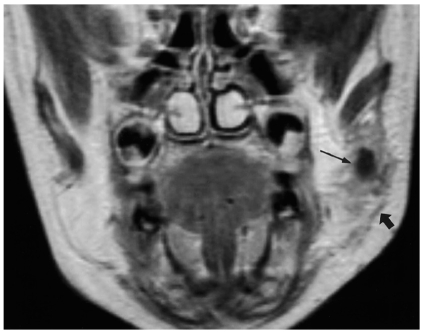

Fig. 3.

Infected dermoid cyst in a 3-year-old girl.

A coronal enhanced T1-weighted MR image shows the cystic mass (thin arrow) in the left buccal space. The mass has an irregular margin and it has infiltrated into the surrounding buccal fat pad. Note the thickening of the superficial muscles of facial expression and the investing fascia (thick arrow).

Hemangioma

Hemangiomas are neoplastic lesions and they exhibit the increased proliferation and turnover of endothelial cells (5). Although they are rarely present at birth, hemangiomas typically become apparent during the first month of life, they rapidly enlarge and ultimately involute by adolescence. On MR imaging, the hemangioma (Fig. 4) demonstrates a higher signal intensity on the progressively more heavily T2-weighted images (6). Enhancement of these lesions following contrast administration is their typical feature.

Fig. 4.

Hemangioma in a 5-year-old girl.

A transverse T2-weighted MR image shows an irregular mass (arrows) having high signal intensity involving the buccal space and the masticator space.

Vascular Malformations

Unlike the hemangiomas, vascular malformations are true congenital vascular anomalies rather than tumors (5). Their endothelial cell proliferation and turnover characteristics are normal, and they demonstrate a slow, steady growth pattern that is commensurate with the growth of the child, and further, they also never involute. There can be capillary, venous, arteriovenous, and lymphatic malformations. Although venous malformations (Fig. 5) may appear very similar to hemangioma, the identification of discrete areas of homogeneous high signal intensity, which represent venous lakes, or the presence of phleboliths may be helpful in suggesting the diagnosis of a venous malformation (6, 7). Arteriovenous malformations demonstrate characteristic serpiginous flow voids on MR imaging (Fig. 6). Lymphatic malformations are cystic masses composed of dysplastic endothelium-lined lymphatic channels that are filled with protein-rich fluid. Lymphatic malformations (Fig. 7) generally appear as cystic and septated lesions with fluid-fluid levels (7).

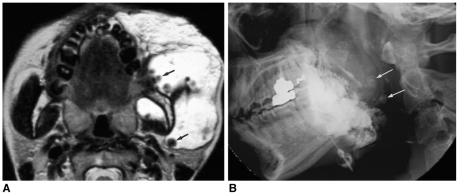

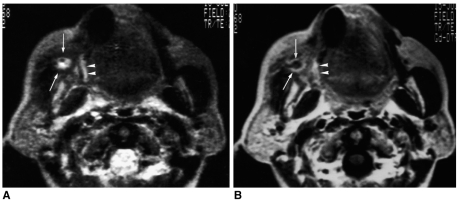

Fig. 5.

Venous malformation in a 22-year-old woman.

A. A transverse T2-weighted MR image shows a high signal intensity mass lesion occupying the buccal space and the masticator space. Note the multiple phleboliths (arrows) having low signal intensity.

B. The lateral radiograph obtained after the percutaneous injection of an ethanolamine oleate and iodized oil mixture shows the radiopaque cast filling the vascular space of the lesion. Note the multiple laminated phleboliths (arrows).

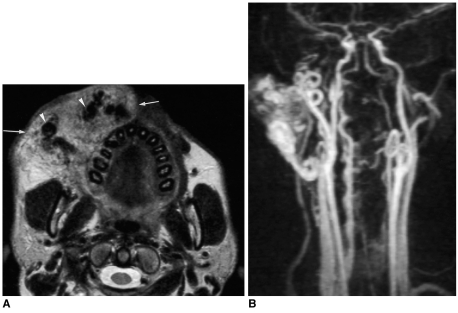

Fig. 6.

Arteriovenous malformation in a 32-year-old man.

A. A transverse T2-weighted MR image shows the intermediate signal intensity mass lesion (arrows) with multiple signal voids (arrowheads) in the right buccal space.

B. A MR angiography shows the tortuous and dilated facial artery and the internal maxillary artery.

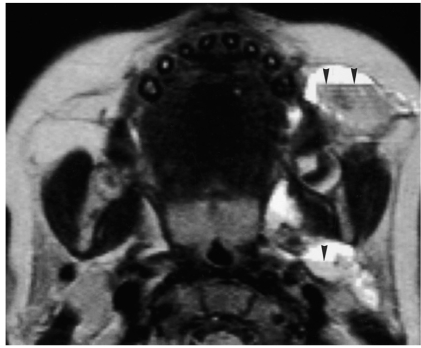

Fig. 7.

Cystic lymphangioma in a 2-year-old boy.

A transverse T2-weighted MR image shows multiple cystic lesions with fluid-fluid levels (arrowheads).

INFECTION AND INFLAMMAROTY LESIONS

Infections within the buccal space commonly result from dental infections, stenosis or calculi that are within the salivary gland ductal systems (2). In many cases, dental infections may primarily involve the masticator space and the infection has secondarily spread to the buccal space. An abscess will appear as a single or multiloculated low-density area with peripheral rim enhancement (Fig. 8). Adjacent muscle enlargement, thickening of the overlying skin and dirty edematous fat are typically present. The presence of these cutaneous and subcutaneous manifestations without a definite low-density collection of is consistent with a cellulitis condition.

Fig. 8.

Abscess in a 60-year-old man.

A transverse enhanced CT scan shows a multiloculated low-density area (thick arrows) with peripheral rim enhancement in the left buccal space, parotid space and parapharyngeal space. Note the right periapical abscesses confined by the right buccinator (thin arrow).

NEOPLASTIC LESIONS

Minor Salivary Gland Tumor

Most of the buccal space tumors have a nonspecific imaging appearance (3). Pleomorphic adenomas are the most common benign glandular tumors and they are characterized by the presence of both mesodermal and glandular tissue. They tend to have a rounded appearance, and they demonstrate low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 9). Adenoid cystic carcinoma (Fig. 10) comprises more than 25% of the malignancies that occur in the minor salivary glands. Masses with a higher signal intensity on the T2-weighted images correspond to those tumors having a low cellularity and a better prognosis, while those tumors with a low signal intensity generally have a dense cellularity and a poor prognosis (8). Generally speaking, the masses having intermediate to low signal intensity on the T2-weighted images or if they display invasion of surrounding tissue planes, then they are more likely to be a malignant lesion (9). However, a small malignant salivary gland tumor (Fig. 11) is likely to have a sharp margin, which mimicks a benign tumor (1).

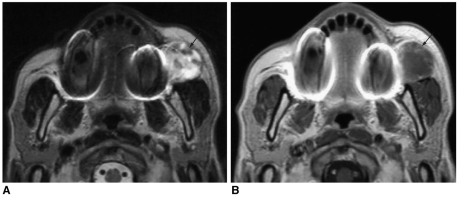

Fig. 9.

Pleomorphic adenoma in a 65-year-old woman.

A. A transverse T2-weighted MR image shows a round, well-defined mass with bright signal intensity in the right buccal space.

B. A transverse T1-weighted MR image shows a round mass with low signal intensity in the right buccal space.

C. An enhanced transverse T1-weighted MR image shows homogeneous enhancement of the lesion.

Fig. 10.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma in a 75-year-old woman.

A. A transverse T2-weighted MR image shows a small round mass (arrows) with central bright signal intensity. Note the ill-defined infiltration of high signal intensity into the right buccinator muscle (arrowheads).

B. An enhanced transverse T1-weighted MR image shows peripheral enhancement (arrows) of the mass. Note the ill-defined infiltration into the right buccinator muscle (arrowheads) with good enhancement.

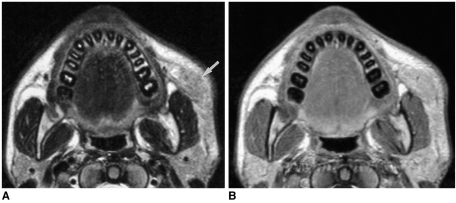

Fig. 11.

Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma in a 70-year-old man.

A. A transverse T2-weighted MR image shows a round mass of bright signal intensity and small, low signal intensity spots in the left buccal space (arrow).

B. An enhanced transverse T1-weighted MR image shows the mildly enhancing foci (arrow).

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcomas are rare malignant mesenchymal tumors, and 36% of these will involve the head and neck (2). Rhabdomyosarcomas appear as muscle density masses on CT, and their signal intensity on the T2-weighted MR images is greater than that of muscle. These tumors tend to infiltrate the surrounding structures and exhibit various degrees of enhancement (Fig. 12).

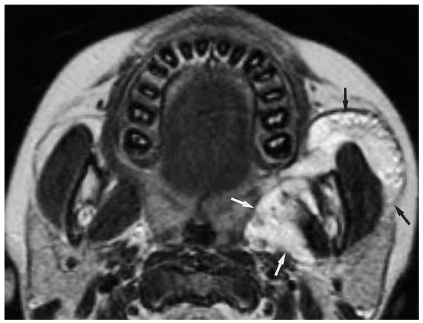

Fig. 12.

Rhabdomyosarcoma in a 15-year-old girl.

A. A transverse T2-weighted MR image shows a round, well-demarcated mass of high signal intensity in the right buccal space.

B. An enhanced coronal T1-weighted MR image shows the heterogeneous enhancement of the lesion.

Neurofibroma

Neurofibromas involving the buccal space are usually associated with neurofibromatosis. Neurofibromas show high signal intensity on the T2-weighted images and they exhibit strong enhancement after the administration of contrast medium (2). The signal of a solitary neurofibroma on the T2-weighted images can be either homogeneously hyperintense or it can show a characteristic target sign with a central hypointense region. The plexiform neurofibroma is seen as an ill-defined, infiltrative lesion that usually involves multiple contiguous neck spaces (Fig. 13).

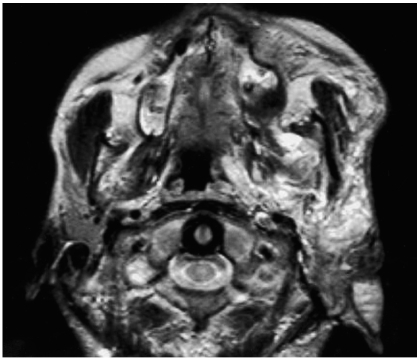

Fig. 13.

Plexiform neurofibroma in a 20-year-old man.

A transverse T2-weighted MR image shows ill-defined high signal intensity mass involving the buccal space, masticator space, parapharyngeal space, parotid space and auricle.

Lymphoma

According to the WHO classification, lymphoid malignancies are largely divided into T-cell neoplasms, B-cell neoplasms, and Hodgkin disease. The imaging characteristics of B-cell lymphomas (Fig. 14) are good demarcation, homogeneity, compression, and molding rather than invasion (10). On the contrary, the imaging features of peripheral T-cell lymphomas (Fig. 15) are nonspecific and infiltrative, and the radiologic differential diagnoses can include bacterial, fungal or parasitic infection, and cutaneous metastases from malignant melanoma or breast cancer (11).

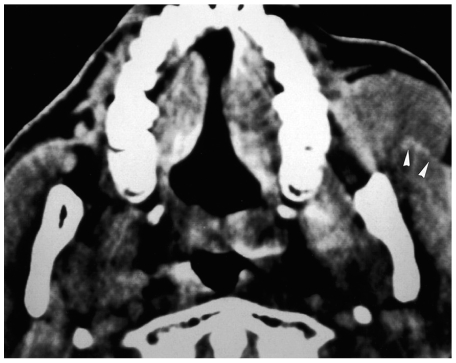

Fig. 14.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the diffuse small cell type in a 49-year-old man. A transverse CT scan shows a homogeneous solid mass in the left buccal space. Note the molding pattern of the mass and the lack of mass effect on the left masseter muscle (arrowheads).

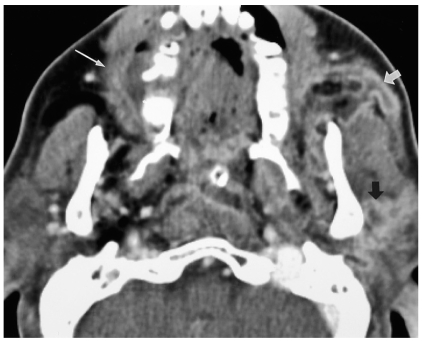

Fig. 15.

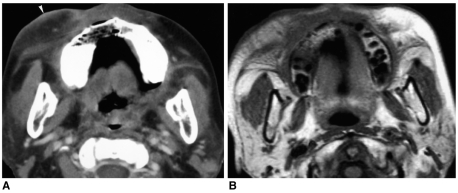

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma in a 57-year-old woman.

A. A transverse CT scan shows the ill-defined infiltrative lesions in both the buccal space and the subcutaneous layer on the right cheek. Note the overlying skin thickening (arrowhead).

B. A transverse T1-weighted MR image shows the ill-defined infiltrative lesions in the same area.

Metastatic Lymph Node

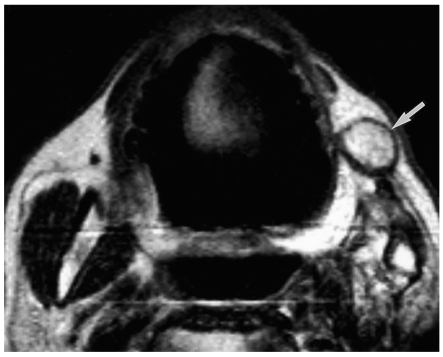

Buccal space lymph node matestasis (Fig. 16) is typically associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the face. It appears as a well-circumscribed mass with rim enhancement and central low attenuation on the CT scan or as high signal intensity on the T2-weighted images (1).

Fig. 16.

Surgically confirmed metastatic lymphadenopathy in a 71-year-old man. A transverse T2-weighted MR image shows a well-circumscribed mass (arrow) with central high signal intensity. The patient underwent left partial mandibulectomy due to squamous cell carcinoma of the gingiva.

MISCELLANEOUS LESIONS

Foreign Body Granuloma

Injection of foreign materials such as paraffin into the breast or face for cosmetic reasons is an uncommon and old method used in the Asian countries. On mammogram, paraffinoma of the breast manifests as multinodular radiopaque opacities with calcifications or as spiculated masses that mimick breast cancer (12). On CT scan of the face, paraffinoma appears as an ill-defined infiltration in the buccal fat pad and the subcutaneous fat with multiple punctate calcifications (Fig. 17). When calcifications associated with soft tissue infiltration are incidentally noticed on CT, particularly bilaterally, the diagnosis of foreign body granulomas secondary to cosmetic cheek augmentation is highly possible and an appropriate review of the medical history is highly recommended.

Fig. 17.

Foreign body granuloma in a 49-year-old woman with a history of paraffin injection into both cheeks 20 years ago. A transverse enhanced CT scan shows the ill-defined infiltration (arrows) and several small calcifications around the bilateral buccal spaces.

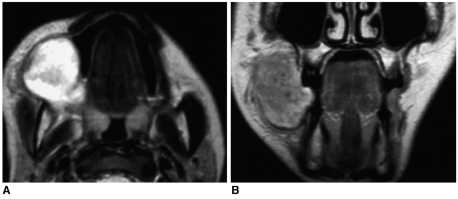

Kimura Disease

Kimura disease is a rare entity that occurs primarily in Asian subjects, and this disease is characterized histopathologically by a lymph-folliculoid granuloma with eosinophil infiltration. The common clinical features are an asymptomatic mass and local lymphadenopathy, particularly in the parotid and submandibular regions. The lesions of Kimura disease (Fig. 18) show a variety of high signal intensities on the T2-weighted images according to the degrees of fibrosis and vascular proliferation, and they show strong enhancement on the enhanced T1-weighted images (13).

Fig. 18.

Kimura disease in a 14-year-old boy.

A. A transverse T2-weighted MR image shows an infiltrative mass-like lesion (arrow) having high signal intensity in the left buccal space.

B. A transverse enhanced T1-weighted MR image shows moderate enhancement of the lesion.

CONCLUSION

There are various pathologies that can occur in the buccal space. Although the purpose for imaging the buccal space lesions is primarily to determine the origin and extent of the lesions, knowledge of the expected CT and MR imaging findings can be helpful for the radiologist to diagnose the specific etiology of the lesions.

References

- 1.Tart RP, Kotzur IM, Mancuso AA, Glantz MS, Mukherji SK. CT and MR imaging of the buccal space and buccal space masses. RadioGraphics. 1995;15:531–550. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.15.3.7624561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smoker WRK. Oral cavity. In: Som PM, Curtin HD, editors. Head and neck imaging. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996. pp. 488–544. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurabayashi T, Ida M, Tetsumura A, Ohbayashi N, Yasumoto M, Sasaki T. MR imaging of benign and malignant lesions in the buccal space. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31:344–349. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurabayashi T, Ida M, Yoshino N, Sasaki T, Kishi T, Kusama M. Computed tomography in the diagnosis of buccal space masses. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1997;26:347–353. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werner JA, Dunne AA, Folz BJ, Rochels R, Bien S, Ramaswamy A, et al. Current concepts in the classification, diagnosis and treatment of hemangiomas and vascular malformations of the head and neck. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;258:141–149. doi: 10.1007/s004050100318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker LL, Dillon WP, Hieshima GB, Dowd CF, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations of the head and neck: MR characterization. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1993;14:307–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kern S, Niemeyer C, Darge K, Merz C, Laubenberger J, Uhl M. Differentiation of vascular birthmarks by MR imaging. An investigation of hemangiomas, venous and lymphatic malformations. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:453–457. doi: 10.1080/028418500127345677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sigal R, Monnet O, de Baere T, Micheau C, Shapeero LG, Julieron M, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: evaluation with MR imaging and clinical-pathologic correlation in 27 patients. Radiology. 1992;184:95–101. doi: 10.1148/radiology.184.1.1319079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah GV. MR imaging of salivary glands. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2002;10:631–662. doi: 10.1016/s1064-9689(02)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HC, Han MH, Kim KH, Jae HJ, Lee SH, Kim SS, et al. Primary thyroid lymphoma: CT findings. Eur J Radiol. 2003;46:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(02)00134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HJ, Im JG, Goo JM, Kim KW, Choi BI, Chang KH, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma: spectrum of imaging findings with clinical and pathologic features. RadioGraphics. 2003;23:7–26. doi: 10.1148/rg.231025018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moon WK, Park JM, Kim YI, et al. Inflammatory and infectious Diseases of the breast: Imaging Findings. Postgraduate Radiol. 2000;20:131–141. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Som PM, Biller HF. Kimura disease involving parotid gland and cervical nodes: CT and MR findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16:320–322. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199203000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]