Abstract

We report here on a 26-year-old pregnant female who developed hirsutism and virilization during her third trimester along with a significantly elevated serum testosterone level. Abdominal US and MR imaging studies were performed, and they showed unique imaging features that may suggest the diagnosis of pregnancy luteoma in the clinical context. After the delivery, the serum testosterone level continued to decrease, and it returned to normal three weeks postpartum. The follow-up imaging findings were closely correlated with the clinical presentation.

Keywords: Ovary, MR; Ovary, neoplasms; Pregnancy; Pregnancy, MR

Pregnancy luteoma was first described by Sternberg and Barclay in 1966 (1), and approximately 200 cases have been reported since then. Most of these patients are asymptomatic with the ovarian enlargement being incidentally discovered at the time of cesarean section or postpartum tubal ligation. Some of these patients will develop hirsutism or virilization during the late pregnancy. In contrast to the histological features that can easily lead to the diagnosis by excisional biopsy of the ovarian lesions, the noninvasive imaging features of this unique entity has not been well reported on. We report here on such a case of pregnancy luteoma that we evaluated and followed with US and MRI.

CASE REPORT

A 26-year-old female (gravida 0, para 0) presented to our prenatal clinic at 35 week's gestation with complaints of deepened voice and excess hair growth over the lower abdomen, face and limbs for two weeks. She was healthy without any significant medical or surgical history, and she was not taking any relevant drug during the pregnancy. The uterine size was consistent with her gestational age. The serum testosterone level was 11,539 ng/dl (normal value: 14-76 ng/dl). The other laboratory examinations showed no additional remarkable findings.

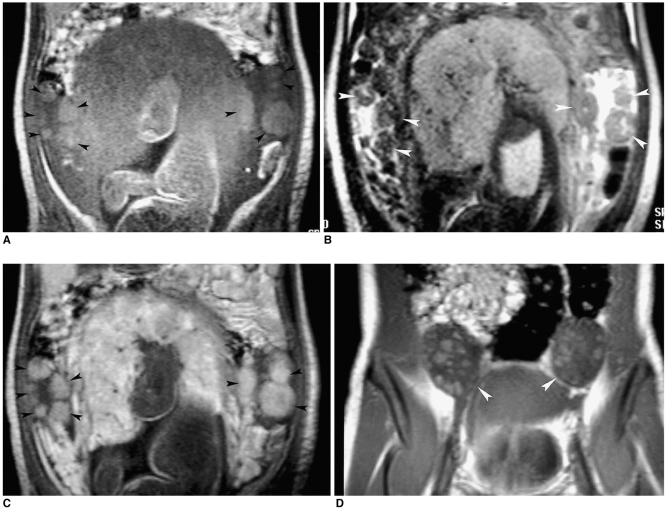

The abdominal US revealed enlargement of the both ovaries with heterogeneous echogenicity. The right ovary measured 4.0×5.2×8.0 cm in size and the left ovary measured 4.5×5.0×7.4 cm; hypervascularity was identified in the both ovaries on color Doppler US. The fetus had a normal sonographic appearance. The patient underwent MR imaging of the pelvis with a 1.5 T MR unit (Magnetom Vision+, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), and this procedure delineated multinodular masses that were distributed peripherally in both ovaries. These masses were characterized as intermediate high signal intensity on the T1-weighted images (Fig. 1A) and low signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 1B). The Gd-DTPA enhanced T1-weighted images (Fig. 1C) showed avid enhancement of the masses that indicated their solid nature and hypervascularity. No evidence of retroperitoneal lymph node enlargement was identified.

Fig. 1.

Pregnancy luteoma. The peripheral-located multinodular ovarian masses (arrowheads) show intermediate high signal intensity on the coronal T1-weighted image (A, 101/4/1 [repetition time/echo time/excitation]), low signal intensity on the T2-weighted image (B, 4/90/1), and avid enhancement on the Gd-DTPA enhanced T1-weighted image (C, 101/4/1). Three weeks postpartum, the coronal Gd-DTPA enhanced T1-weighted image (D) show the greatly diminished size of the enhancing ovarian masses, although the ovaries (arrowheads) remain large.

Based on the clinical and imaging findings, pregnancy luteoma was the first diagnostic impression. One week later, the patient spontaneously delivered a girl with an enlarged clitoris. At two days postpartum, the serum testosterone level dramatically dropped to 2,676 ng/dl and the level returned to normal three weeks later. The ovarian masses correspondingly decreased in size on both the follow-up US and MR imaging (Fig. 1D). Two months postpartum, US revealed normalized bilateral ovaries with improvement of patient's hirsutism, but the girl's clitoris remained enlarged.

DISCUSSION

During a normal pregnancy, the maternal circulating testosterone level can increase and especially in the third trimester. The serum levels of total testosterone may rise up to seven times the nonpregnant levels, and this physiological condition does not cause virilization. Virilization during pregnancy is a rare clinical event, and it is most commonly caused by pregnancy luteoma or hyperreactio luteinalis. Both are benign tumors that are characterized by spontaneous disappearance of the tumors and normalization of the androgen levels after the delivery. In addition, malignant androgen-producing Sertoli-Leydig-cell tumor, nonfunctioning Krukenberg tumor and mucinous cystadenoma of the ovary have been reported as causing virilization of pregnant women (2-4). However, these later tumors do not regress after delivery, which is distinct from pregnancy luteoma and hyperreactio luteinalis.

Pregnancy luteoma is a non-neoplastic hormone-dependent lesion characterized by ovarian enlargement during pregnancy, and this can simulate a tumor. Human chorionic gonadotropin is believed to be the most important hormone contributing to this condition. However, luteomas are rarely noted in trophoblastic diseases, which are associated with high levels of human chorionic gonadotropin, and this indicates that there are other unknown factors causing the luteomas. Within the ovary, it is the stromal cells rather than the follicles that are being stimulated. Since the stromal cells produce androgen, virilization of the mother and fetus can occur in 25% to 30% of these cases (5). Some of these lesions are hormonally inactive and are often found incidentally during cesarean section or postpartum tubal ligation. Most pregnancy luteomas resolve completely by three months postpartum and the serum testosterone level usually reaches a normal concentration within two weeks postpartum (6). No treatment is required for this benign self-limited condition.

In contrast to pregnancy luteoma, hyperreactio luteinalis is characterized by bilateral ovarian enlargement that is due to the presence of numerous luteinized follicular cysts. No cases of virilization of the newborn have been reported in hyperreactio luteinalis, even when there is virilization of the mother and elevated cord blood androgen levels (7). Hence, given the clinical features of the patient and the solid nature of the ovarian masses, the diagnosis of pregnancy luteoma was established in our case, although no surgical specimen was obtained.

Pregnancy luteoma is estimated to be bilateral in one third of the cases and multinodular in half of the cases (6). The lesions can vary, and they measure from microscopic size to over 20 cm in diameter. Upon gross examination, luteomas are characterized as soft, reddish tan, fleshy, circumscribed areas with frequent foci of hemorrhage (6). Microscopic examination discloses the presence of sharply circumscribed rounded masses of cell with follicles containing pale fluid or colloid material (8). The histological features of the pregnancy luteoma were well correlated with the MR imaging findings in our case. The presence of contrast enhancement indicates the hypervascular nature of the solid masses. In our case, the relative intermediate high signal intensity on the T1-weighted images and the low signal intensity on the T2-weighted images were presumably contributed to by the colloid material in the cells. On follow-up MR imaging, the masses showed a marked decrease in size corresponding to the reduced level of serum testosterone.

The MR imaging findings of pregnancy luteoma have only been reported on once in the literature, and this was a case of bilateral multilobulated cystic ovarian masses with thick septa that were incidentally identified in an asymptomatic woman at 32 weeks of gestation (9). In our case, the enhanced solid nature of ovarian masses may have been connected to the symptomatic clinical presentation, which was in contrast to the aforementioned "silent" case. Of the other solid tumors of pregnancy with virilization, Krukenberg tumors can also exhibit a characteristic low signal intensity on the T2-weighted images, and prominent enhancement will be noted to involve the bilateral ovaries (10). However, this type of tumor tends to have various amounts of cystic components, and this was not observed in our case.

In conclusion, MR imaging is a valuable adjunctive modality for evaluating adnexal masses that occur in pregnancy. A good appreciation of the clinical and imaging features of pregnancy luteoma can obviate the requirement of an unnecessary operation or the interruption of pregnancy.

References

- 1.Sternberg WH, Barclay DL. Luteoma of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1966;95:165–184. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(66)90167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young RH, Dudley AG, Scully RE. Granulosa cell, Sertoli-Leydig cell, and unclassified sex cord-stromal tumors associated with pregnancy: a clinicopathological analysis of thirty-six cases. Gynecol Oncol. 1984;18:181–205. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(84)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forest MG, Orgiazzi J, Tranchant D, Mornex R, Bertrand J. Approach to the mechanism of androgen overproduction in a case of Krukenbery tumor responsible for virilization during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978;47:428–434. doi: 10.1210/jcem-47-2-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pascal RR, Grecco LA. Mucinous cystadenoma of the ovary with stromal luteinization and hilar cell hyperplasia during pregnancy. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:179–180. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(88)80345-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Bunuel R, Berek JS, Woodruff JD. Luteomas of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;45:407–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clement PB. Tumor-like lesions of the ovary associated with pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12:108–115. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tinkanen H, Kuoppala T. Virilization during pregnancy caused by ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:476–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joshi R, Dunaif A. Ovarian disorders of pregnancy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1995;24:153–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang HK, Sheu MH, Guo WY, Hong CH, Chang CY. Magnetic resonance imaging of pregnancy luteoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:155–157. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ha HK, Baek SY, Kim SH, Kim HH, Chung EC, Yeon KM. Krukenberg's tumor of the ovary: MR imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:1435–1439. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.6.7754887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]