Abstract

Objective

We wanted to evaluate the feasibility and usefulness of a newly designed balloon sheath for gastrointestinal guidance and access by conducting a phantom study.

Materials and Methods

The newly designed balloon sheath consisted of an introducer sheath and a supporting balloon. A coil catheter was advanced over a guide wire into two gastroduodenal phantoms (one was with stricture and one was without stricture); group I was without a balloon sheath, group ll was with a deflated balloon sheath, and groups III and IV were with an inflated balloon and with the balloon in the fundus and body, respectively. Each test was performed for 2 minutes and it was repeated 10 times in each group by two researchers, and the positions reached by the catheter tip were recorded.

Results

Both researchers had better performances with both phantoms in order of group IV, III, II and I. In group IV, both researchers advanced the catheter tip through the fourth duodenal segment in both the phantoms. In group I, however, the catheter tip never reached the third duodenal segment in both the phantoms by both the researchers. The numeric values for the four study groups were significantly different for both the phantoms (p < 0.001). A significant difference was also found between group III and IV for both phantoms (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The balloon sheath seems to be feasible for clinical use, and it has good clinical potential for gastrointestinal guidance and access, particularly when the inflated balloon is placed in the gastric body.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal tract; Interventional procedure; Model, anatomical

Gastrointestinal strictures are usually caused by malignant tumor or by postoperative stenoses (1-3). Such interventional therapy as balloon dilation and/or stent placement for patients with gastric outlet strictures or duodenal strictures is well known to be simple, safe and effective palliative therapy (1-8). However, the tortuousness of the access route and a dilated flaccid stomach can make it very difficult to manipulate interventional devices through the strictures. Some authors have stressed the difficulty of passing the delivery system through the strictures of the gastric outlet and the duodenum because of the loop formation of the delivery system in the dilated stomach (5-7). Therefore, interventional procedures can be time-consuming and they can sometimes fail in complex cases (5-7).

To solve this problem, an endoscope has been used by some groups of physicians to support the interventional devices as they pass through the dilated stomach (2, 8, 9). Stent placement via percutaneous gastrostomy or the percutaneous transhepatic route has also been reported (5, 10, 11). However, there are some limitations related to the endoscopic or percutaneous approach, such as the discomfort of the endoscope, and the risk of bleeding, infection and leakage of the enteric fluid associated with the percutaneous approaches (8, 9).

Therefore, a balloon sheath was designed by the authors of this study to provide additional stability for the interventional devices as they pass through the stomach. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and usefulness of the newly developed balloon sheath for gastrointestinal guidance and access by conducting a phantom study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Balloon Sheath Construction

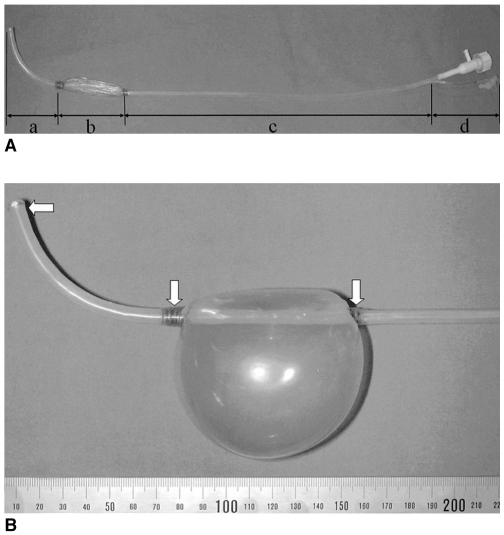

The home-made balloon sheath mainly consisted of an introducer sheath and a supporting balloon (Figs. 1A, B). It was divided into four parts: the distal angulated part, the balloon part, the straight part, and the proximal handling part (Fig. 1A). The introducer sheath was made of a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tube (Sang-A Flontec Co., Incheon, Korea) with a 4.2 mm inner diameter, a 4.8 mm outer diameter and a 60 cm length. The distal part of the sheath was 8.0 cm in length and it was bent at a 100° angle. A side supporting balloon (8.0 cm in length) was made of latex tube (Unidus Co., Seoul, Korea), and this was attached to the sheath with nylon strings (Teleflex Medical, Coventry, CT, USA). The balloon was designed to point to the opposite side of the angulated tip when it was inflated. A polyetheretherketon (PEEK) tube (Victrex, Orangeburg, SC, USA) was used as the balloon inflating side tube, and this was connected to the proximal part of the balloon. Polyetheretherketon has excellent flexibility and resistance to chemicals. The polyetheretherketon side tube had a 1.0 mm inner diameter and a 1.3 mm outer diameter. The proximal end of the PEEK side tube was connected with a side-arm that included a three-way stopcock (Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA). The straight part constituted the main part of the introducer sheath (44 cm in length) and it ran parallel with the PEEK side tube. The distal angulated part and the straight part of the introducer sheath were covered with a heat-shrinkable tube (6.0 mm outer diameter) (LG Cable, Anyang, Korea). The chemical-resistant heat-shrinkable tube was used to tightly wrap the both ends of the side supporting balloon (nylon-strings) as well as to mount the straight part of the introducer sheath and the PEEK side tube together. Three radiopaque gold rings (0.1 mm in thickness and 1.0 mm in width) were attached to the sheath with glue at both ends of the balloon and at the distal tip of the sheath; these acted as markers to improve the radiopacity of the sheath. Last, a plastic handling hub (S&G Biotech, Seoul, Korea) was connected to the proximal end of the sheath.

Fig. 1.

The new balloon sheath.

A. The deflated balloon sheath. (a) the distal angulated part, (b) the balloon part, (c) the straight part, and (d) the proximal handling part.

B. The inflated balloon sheath and the three gold markers (arrows) at each end of the balloon and at the tip of the balloon sheath.

Gastroduodenal Phantom

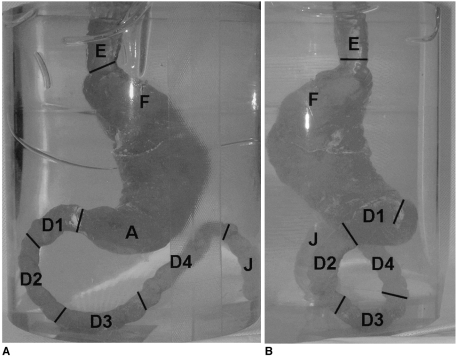

Two types of silicone phantom models were made for the balloon sheath study: one simulated a normal anatomic condition, and the other simulated a 70% concentric stenosis at the gastroduodenal junction. First, a paper plaster clay model was made according to the anatomy and size of a normal human stomach and duodenum. It included the lower part of the esophagus, the entire stomach, the duodenum and the proximal portion of the jejunum. Second, after the model had dried for three days, it was put in a lucent molding box. Fluid silicone (Shin-Etsu Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was poured into the molding box, and it was allowed to harden. At last, the paper/plaster/clay was completely removed from the hardened silicone. The gastroduodenal phantom was divided into several portions according to the normal human anatomy, including the lower part of the esophagus, the gastric fundus, the gastric body, the gastric antrum, the duodenum and the proximal portion of the jejunum. The duodenum of the phantom was approximately 35 cm in length and it was divided into four segments: the first duodenal bulb portion segment, the second descending portion segment, the third horizontal portion segment and the forth ascending portion segment (Figs. 2A, B). The gastroduodenal junction was angled at about 90° in a posterior direction relative to the long axis of the gastric antrum (Fig. 2B). The phantom gastroduodenal tract was clearly visible under fluoroscopy.

Fig. 2.

Photograph of the silicone phantom model without stricture and filled with red ink.

A. Anteroposterior view.

B. Lateral view. The gastroduodenal junction is angled about 90° in a posterior direction to the long axis of the gastric antrum. E = esophagus, F = fundus, A = antrum, D1 = first segment of duodenum, D2 = second segment of duodenum, D3 = third segment of duodenum, D4 = fourth segment of duodenum, J = proximal portion of the jejunum.

Experiments

A 150 cm, 0.035-inch hydrophilic guide wire with an angled tip (Radifocus, M-Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) and a multifunctional coil catheter (S&G Biotech, Seoul, Korea) were used in our phantom study. The multifunctional coil catheter was designed to measure the length of the lesion as well as to inject the contrast medium to opacify the area of interest while the guide wire was in place (12, 13). We used the multifunctional coil catheter in this study because we have been using this catheter for interventional procedures in the gastrointestinal tract since August 2000.

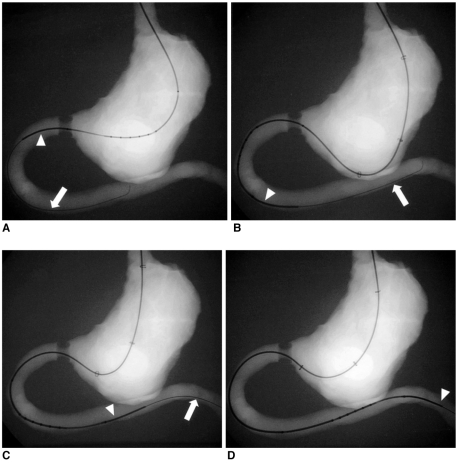

The balloon sheath experiments were classified into four groups and the tests were repeated ten times in each group. During each test, the coil catheter was advanced as far as possible into the duodenum or jejunum of the gastroduodenal phantom. In group I, the coil catheter was advanced only over the guide wire as far as possible into the phantom (Fig. 3A). In group II, the coil catheter was advanced over the guide wire as far as possible through the deflated balloon sheath into the phantom to simulate the sheath without the balloon (Fig. 3B). In group III and group IV, the coil catheter was advanced as far as possible over the guide wire through the inflated balloon sheath into the phantom. Therefore, the inflated sheath balloon was placed in the gastric fundus in group III and it was placed in the gastric body in group IV (Figs. 3C, D). Because the distal angulated part of the balloon sheath should be located proximal to the stricture area at the gastroduodenal junction, the balloon part of the balloon sheath could not be placed as far as in the gastric antrum. The balloon was inflated with air by using a 50 cc syringe until it impinged on the greater curvature. The balloon diameter that was perpendicular to the long axis of the sheath was 7 cm after injecting 50 cc of air.

Fig. 3.

Radiographies of a coil catheter (arrowheads) being advanced over a guide wire (arrows) into the gastroduodenal phantom with stricture in the four groups.

A. Group I, without a balloon sheath.

B. Group II, through the deflated balloon sheath.

C. Group III, through the inflated balloon sheath with the inflated balloon located in the gastric fundus.

D. Group IV, through the inflated balloon sheath with the inflated balloon located in the gastric body.

The surface of the coil catheter was not lubricated with any lubricant. In every test, the total procedure time lasted for two minutes, and the position that was reached by the tip of the coil catheter was recorded. The two-minute time started with the insertion of the coil catheter in group I, and the two-minute time started with insertion of the balloon sheath in groups II - IV. All the tests were performed by the two interventional radiologists. The tests were performed for ten consecutive days, and each group with each type of phantom was tested one time per day to reduce the learning effects.

Statistical Analysis

The positions reached by the tip of the catheter were numerically ordered; the first, second, third and fourth segments, and the proximal portion of the jejunum were encoded as 1-4 and 5, respectively. The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to evaluate if there were significant differences among the four groups because the catheter tip position was treated as an ordinal variable. If the Kruskal-Wallis test showed a statistical difference, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare groups III and IV to determine the best location of the inflated balloon between the gastric body and fundus for the advancement of the catheter tip. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 10.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

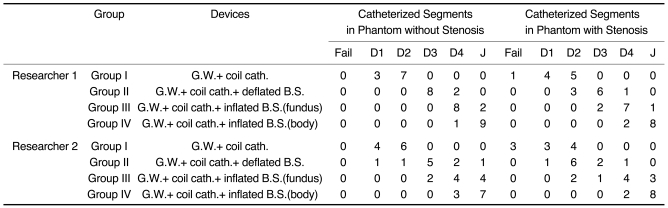

The results are summarized in Table 1. Both researchers had better performances with both phantoms in order of group IV, III, II and I. In group IV, both researchers advanced the tip of coil catheter through the fourth segment of the duodenum in both phantoms. In group III, each researcher advanced the tip of the coil catheter as far as the fourth segment of the duodenum 10 and eight times, respectively, in the phantoms without stricture, and eight and seven times, respectively, in the phantoms with stricture. In group II, each researcher succeeded in catheterizing the fourth segment of the duodenum twice and three times, respectively, in the phantoms without stricture, and once and once, respectively, in the phantoms with stricture. In group I, however, both researchers failed to reach the third segment of the dueodenum in both phantoms with the tip of the coil catheter. The overall performance for the phantom with stricture was similar with that for the phantom without stricture, although each researcher failed to catheterize the stricture once and three times, respectively.

Table 1.

The Results of the Four Phantom Study Groups

Note.-G.W. = guide wire, cath. = catheter, B.S. = balloon sheath, D1 = first segment of the duodenum, D2 = second segment of the duodenum, D3 = third segment of the duodenum, D4 = fourth segment of the duodenum, J = the proximal portion of the jejunum

Statistical analysis of the differences in the positions reached by the tip of the catheter among the four groups in each phantom showed a significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis test, p < 0.001). When comparing the mean values of the catheter tip advancement between groups III and IV in each phantom, there were significantly higher mean values for group IV than for group III (Mann-Whitney U test, p < 0.001). The results showed that the tip of the coil catheter could easily reach the proximal portion of the jejunum when we worked through an inflated balloon sheath, especially when the inflated balloon was placed in the gastric body.

DISCUSSION

The newly designed balloon sheath was helpful to negotiate a catheter and guide wire through the stomach and into the duodenum or proximal jejunum. Negotiation of the catheter and guide wire was best when the inflated balloon sheath was placed in the gastric body. The distal angulated part of the balloon sheath that was 8 cm in length and it had a 100° angle that effectively allowed us to direct the devices toward the pylorus because the balloon, which was designed to point to the opposite side of the angulated tip, could push the lower part of the sheath toward the pyloric canal and against the greater curvature of the stomach wall when the balloon was inflated with air.

During gastrointestinal interventional procedures, one of the most important steps for a successful procedure is to pass a guide wire and a catheter through the gastric outlet or through the duodenal obstructions (4, 10-11, 14-17). However, when the strictures are severe, the gastric contents may accumulate in the stomach and the gastric cavity becomes dilated and flaccid. When a guide wire and a catheter cannot negotiate through the strictures, they are readily curved in the dilated stomach. In order to overcome this technical problem, various angiographic catheters have been used in combination with a torque-control guide wire to traverse the strictures. However, some of the strictures cannot be passed with this technique. The reported failure rate of fluoroscopically guided stent placement for gastroduodenal strictures has been reported to be between 1% and 5%, even after additional endoscopic assistance, and the average time needed for fluoroscopically guided stent placement has been reported to be from 36 to 45 minutes (1, 5, 17).

The newly designed balloon sheath seems to have several advantages. First, as the outer diameter of the balloon sheath (maximum outer diameter; 7.3 mm) is smaller than that of the routine gastroduodenal endoscope (outer diameter; 9.6 mm) (GIF 100; Olympus, Southend-on-Sea, UK), the balloon sheath could be well tolerated during the procedure. Meanwhile, the inner diameter of the working channel of the same endoscope is 2.7 mm, which is smaller than that of the balloon sheath (4.2 mm). Second, the inflated supporting balloon can give extra-stability to the tip of the balloon sheath in order to prevent it from looping and moving backward in the stomach while the guide wire, the catheter or the delivery system is passing through. The ideal gastric sheath should have such appropriate physical characteristics as suitable torque and supportability. If the sheath is too rigid, it can injure the mucosa of the upper digestive tract and the patients may not be able to tolerate the device during the procedure. Third, the balloon sheath can be easily inserted perorally into the stomach, and it is effective in guiding the interventional devices to the duodenum or jejunum.

We classified our phantom study into four groups. In group I, while the coil catheter was advanced over a guide wire into the duodenum, it usually looped along the wall of the greater curvature and the gastric fundus, and so it could not be advanced further. In group II, while the coil catheter was advanced over a guide wire into the duodenum through the deflated balloon sheath, the devices could not be advanced further than the greater curvature of the stomach wall. In group III and group IV, while the coil catheter was advanced over a guide wire into the distal duodenum or proximal jejunum through the inflated balloon sheath, the inflated balloon gave extra-stability against the wall of the gastric fundus or the gastric body, so that the tip of the coil catheter could reach as far as the proximal jejunum. When the inflated balloon was placed in gastric body rather than being placed in the gastric fundus, it was easier to advance the catheter as far as the proximal jejunum. We think that the balloon sheath enables the devices to advance into the more distal areas adjacent to the pylorus by changing the direction of the tip of the devices more towards the gastroduodenal junction.

Although a gastroduodenal phantom was useful for testing the newly designed balloon sheath, there were some limitations for this study. First, the gastroduodenal phantom model that we made out of silicone had no elasticity like a human gastroduodenal wall. Second, the model did not resemble a dilated stomach. It would have been better to use an ideal model that mimicked the real human gastroduodenum; however, it was difficult to make a satisfactory gastroduodenal phantom model because there is a lot of variability in curvature, size and shape of the stomach. Third, we could not place the balloon part of the balloon sheath in the gastric antrum because the stricture was made at the gastroduodenal junction and the distal angulated part had to be located proximal to the stricture in this experiment. If we could have made the stricture at the second or third segment of duodenum, we could have compared the results according to the location of inflated balloon between the gastric antrum and gastric body.

In conclusion, the new balloon sheath displayed good results in the gastroduodenal phantom study, especially when the inflated balloon was placed in the gastric body. The new balloon sheath seems to be feasible for use and it has good clinical potential for fluoroscopically guided gastrointestinal guidance and access.

Acknowledgment

We thank Bonnie Hami, MA, Department of Radiology, University Hospitals Health System, Cleveland, Ohio, for her editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The study was supported by a grant (#HMP-00-B-31400-00169) from the Highly Advanced National Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Jung GS, Song HY, Kang SG, Huh JD, Park SJ, Koo JY, et al. Malignant gastroduodenal obstructions: treatment by means of a covered expandable metallic stent-initial experience. Radiology. 2000;216:758–763. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00au05758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mauro MA, Koehler RE, Baron TH. Advances in gastrointestinal intervention: the treatment of gastroduodenal and colorectal obstructions with metallic stents. Radiology. 2000;215:659–669. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.3.r00jn30659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holt PD, de Lange EE, Shaffer HA., Jr Strictures after gastric surgery: treatment with fluroscopically guided balloon dilation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:895–899. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.4.7726043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binkert CA, Jost R, Steiner A, Zollikofer CL. Benign and malignant stenoses of the stomach and duodenum: treatment with self-expanding metallic endoprostheses. Radiology. 1996;199:335–338. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.2.8668774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung GS, Song HY, Seo TS, Park SJ, Koo JY, Huh JD, et al. Malignant gastric outlet obstructions: treatment by means of coaxial placement of uncovered and covered expandable nitinol stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61720-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park KB, Do YS, Kang WK, Choo SW, Han YH, Suh SW, et al. Malignant obstruction of gastric outlet and duodenum: palliation with flexible covered metallic stents. Radiology. 2001;219:679–683. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.3.r01jn21679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yates MR, 3rd, Morgan DE, Baron TH. Palliation of malignant gastric and small intestinal strictures with self-expandable metal stents. Endoscopy. 1998;30:266–272. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Razzaq R, Laasch HU, England R, Marriott A, Martin D. Expandable metal stents for the palliation of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2001;24:313–318. doi: 10.1007/s00270-001-0031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caldicott DG, Ziprin P, Morgan R. Transhepatic insertion of a metallic stent for the relief of malignant afferent loop obstruction. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2000;23:138–140. doi: 10.1007/s002709910027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JM, Han YM, Kim CS, Lee SY, Lee ST, Yang DH. Fluoroscopic-guided covered metallic stent placement for gastric outlet obstruction and post-operative gastroenterostomy anastomotic stricture. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:560–567. doi: 10.1053/crad.2001.0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acunas B, Poyanli A, Rozanes I. Intervention in gastrointestinal tract: the treatment of esophageal, gastroduodenal and colorectal obstructions with metallic stents. Eur J Radiol. 2002;42:240–248. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(02)00031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin JH, He X, Lee JH, Seo TS, Lim JO, Kim TH, et al. Newly designed multifunctional coil catheter for gastrointestinal intervention: feasibility determined by experimental study in dogs. Invest Radiol. 2003;38:796–801. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000091653.56737.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song HY, Shin JH, Lim JO, Kim TH, Lee GH, Lee SK. Use of a newly designed multifunctional coil catheter for stent placement in the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:369–373. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000121406.46920.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zollikofer CL, Jost R, Schoch E, Decurtins M. Gastrointestinal stenting. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:329–341. doi: 10.1007/s003300050053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JH, Yoo BM, Lee KJ, Hahm KB, Cho SW, Park JJ, et al. Self-expanding coil stent with a long delivery system for palliation of unresectable malignant gastric outlet obstruction: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2001;33:838–842. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinto IT. Malignant gastric and duodenal stenosis: palliation by peroral implantation of a self-expanding metallic stent. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1997;20:431–434. doi: 10.1007/s002709900188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song HY, Song HY, Shin JH, Lee GH, Kim TW, Lee SK, et al. A dual expandable nitinol stent: experience in 102 patients with malignant gastroduodenal strictures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:1443–1449. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000142594.31221.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]