I. Introduction

a. Pericellular Proteolysis

Enzymes in the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family have been linked to key events in developmental biology since the first discovery of collagenolytic activity in amphibians undergoing metamorphosis by Gross and Lapiere in 1962 1. A plethora of subsequent biochemical, cellular and in vivo analyses have established that pericellular proteolysis contributes to numerous aspects of ontogeny, including ovulation, fertilization, implantation, cellular migration, tissue remodeling and repair. Stringent control of proteolysis is essential for maintenance of tissue integrity and homeostasis, and multiple mechanisms have evolved for both systemic and highly localized control of proteolytic activity 2, 3. An effective mechanism for post-translational control of substrate processing is to anchor proteinases to the cell surface via a transmembrane domain, glycosyl-phosphatidyl inositol (GPI) anchor, or surface-localized proteinase receptor. Surface anchoring thereby provides spatial restrictions on substrate targeting and may afford protection from circulating proteinase inhibitors 4. This review will utilize membrane type 1 (MT1)-MMP as an example to highlight substrate diversity in pericellular proteolysis. This captivating proteinase was originally discovered based on its ability to catalyze cell surface-associated processing of a soluble substrate, proMMP-2 5, 6. In recent years, however, a wealth of additional protein and polypeptide MT1-MMP substrates have been described, providing abundant examples to illustrate the diverse functional consequences of pericellular proteolytic processing of matrix, soluble, and cell surface-associated substrates.

b. MT1-MMP Structure

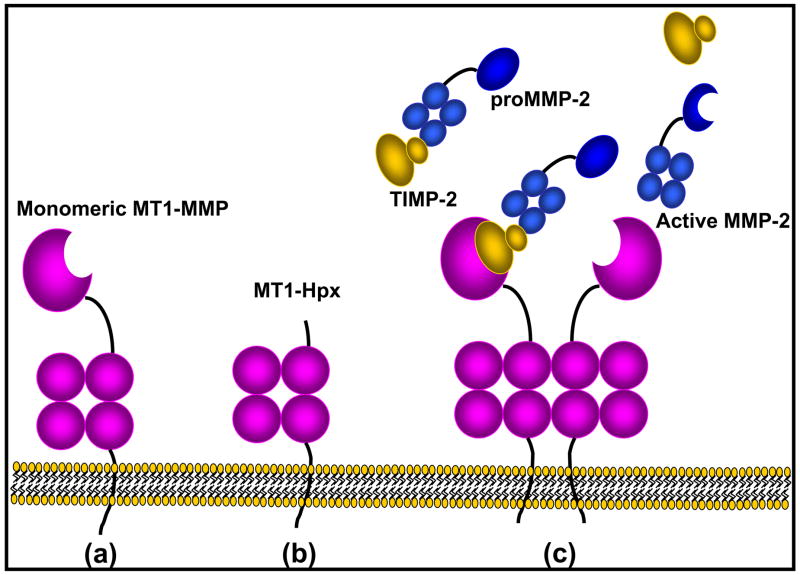

MT1-MMP is comprised of seven domains, including a pre/propeptide (M1 – R111), a catalytic domain (Y112 – G285) containing the Zn++-binding consensus region, a hinge or linker region (E286 – I318), hemopexin domain (C319 – C508), stalk region (P509 – S538), transmembrane domain (A539 – F562), and a cytoplasmic tail (R563 – V582 )6–10 [Fig. 1]. The enzyme is expressed as a zymogen (proMT1-MMP) containing a furin recognition motif (R108–R111) between the pro- and catalytic domains and is processed by proprotein convertases such as furin in the secretory pathway 11, 12. MT1-MMP is thereby presented to the cell surface in active form and recent data suggest that zymogen activation may actually be a pre-requisite for plasma membrane trafficking of the proteinase 13, 14. In addition to the catalytically competent 55–60 kDa active species, proteolytic processing generates a membrane anchored form [Fig. 1] lacking the catalytic domain 15–19. This 44–45 kDa hemopexin domain-containing species may play a role in regulating activity of the mature enzyme 20–23.

Fig. 1. Domain structure of MT1-MMP.

(a) Mature membrane-anchored MT1-MMP is comprised of a catalytic domain (Y112-G285) containing the Zn++-binding consensus sequence, a hinge region (E286-I318), hemopexin-like domain (C319-C508), a membrane-adjacent stalk region (P509-S538), a transmembrane domain (A539-F562) and a cytoplasmic tail (R563-V582). (b) MT1-MMP undergoes autolytic processing at G284-G285 to generate a membrane-anchored species lacking the catalytic domain but retaining a surface-localized hemopexin domain that regulates activity of the mature enzyme. (c) MT1-MMP-catalyzed activation of proMMP-2 involves two molecules of MT1-MMP, likely functioning as a dimeric unit. One member of the complex forms a trimeric activation complex comprised of MT1-MMP, TIMP-2 and proMMP-2. The proMMP-2 in the trimeric complex is properly positioned for efficient activation by TIMP-2-free MT1-MMP, generating active MMP-2.

II. Processing of Extracellular Matrix Substrates

a. MT1-MMP as an interstitial collagenase

Shortly after discovery of the enzyme, early biochemical studies using active MT1-MMP retaining the hemopexin domain demonstrated the ability of MT1-MMP to process interstitial collagens I, II, and III in vitro, producing the ¾ and ¼ fragments characteristic of mammalian collagenases 24, 25. Generation of mice deficient in MT1-MMP expression provided strong genetic evidence to support the in vitro data, demonstrating a key role for MT1-MMP as an interstitial collagenase during development. MT1-MMP−/− mice exhibited severe connective tissue abnormalities including dwarfism, osteopenia, soft tissue fibrosis, arthritis and skeletal dysplasia resulting from the inability to process interstitial collagen during development 26, 27. Lack of MT1-MMP activity also resulted in aberrant cranial morphogenesis and suture formation, due to the persistence of cartilage primordia in intramembranous ossification 26. Defective vascularization was also observed, both in the cartilage of growth plates and in a corneal angiogenesis assay, suggesting a role for MT1-MMP in initiating angiogenesis 27. Furthermore, skin fibroblasts isolated from MT1-MMP−/− mice were deficient in collagenolytic activity, leading to a defect in stromal remodeling 26.

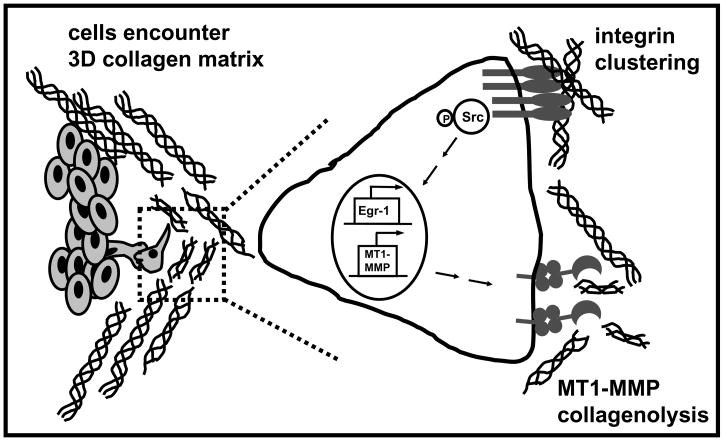

Further evidence attributing the ability of migrating cells to traverse type I collagen-rich tissue barriers to MT1-MMP-catalyzed pericellular collagenolytic activity was provided from cell culture studies. Transfection of MDCK cells with a variety of MMPs, followed by growth factor stimulation and analysis of invasion and tubulogenesis in 3-dimensional collagen gels, showed that membrane anchoring was required to properly position type I collagenase activity on the cell surface for effective pericellular collagenolysis 28. Surface MT1-MMP activity also potentiated invasion of 3-dimensional collagen gels by carcinoma cells in vitro and of collagen-rich bone matrix in vivo [Fig. 2 and 2, 23, 29–33. In addition to modulating motility by matrix clearance, MT1-MMP-catalyzed pericellular collagenolysis conferred a growth advantage to cells in 3-dimensional collagen environments by enabling cells to remove matrix barriers that constrain cell shape and prohibit cytoskeletal alternation and associated proliferative responses 34. Modulation of pericellular collagen rigidity by MT1-MMP-mediated proteolysis also controls adipogenesis 35 and osteocytogenesis 36, providing evidence for a key role of MT1-MMP-catalyzed collagen cleavage in normal development as well as neoplasia. Evidence for reciprocal regulation of MT1-MMP by collagen has been generated in numerous model systems that show type I collagen induces MT1-MMP expression and surface activity via integrin signaling and/or cytoskeletal alterations 15, 37–42, further supporting the importance of MT1-MMP in collagen homeostasis [Fig. 3].

Fig. 2. Collagenolytic activity of MT1-MMP.

(A, B) OvCa433 cells, with low endogenous MT1-MMP expression were transfected with either (A) a catalytically inactive (E240A mutant) or (B) wild type MT1-MMP and subcultured onto type I collagen gels containing quenched fluorescent type I collagen (DQ-collagen, Invitrogen). This collagen substrate is heavily conjugated with multiple fluorescein labels, leading to quenched fluorescence in the intact substrate. Upon hydrolysis to single dye labeled products, quenching is relieved yielding green fluorescent products indicative of collagenase activity. Note the pericellular collagenolysis in cells expressing wild type active MT1-MMP (B). (C) Invasion of type I collagen gels. OvCa433 cells transfected with wild type or catalytically inactive mutant (E240A) MT1-MMP or vector controls were seeded onto Transwell filters coated with a type I collagen gel and allowed to invade for 24 hr. Non-invading cells were removed from the upper chamber with a cotton swab prior to staining and enumeration of cells adherent to the underside of the filter using an ocular micrometer. Data from triplicate experiments are presented with S.D. value shown (*p<.005). (Figures courtesy of Yueying Liu.)

Fig. 3. Reciprocal regulation of MT1-MMP expression by collagen.

Migrating cells encountering a three-dimensional collagen matrix engage collagen via integrin-mediated attachments. Clustering of integrins resulting from interaction with 3-dimensional collagen induces phosphorylation of Src kinases, resulting in induction of the transcription factor Egr-1 and transcriptional activation of the MT1-MMP promoter. The active proteinase is trafficked to the cell surface where it participates in pericellular collagenolysis.

b. MT1-MMP Processing of Adhesive Glycoproteins and Proteoglycans

In addition to degradation of interstitial collagens, MT1-MMP has also been implicated in the cleavage of a variety of adhesive glycoproteins including fibronectin 24, 25, 42, laminin 24, 43, 44, vitronectin 24, tenascin, nidogen 25, fibrin and fibrinogen 45–49. Laminin processing has been the most extensively studied, following an initial report that MT1-MMP promoted processing of the rat laminin-5 γ2 subunit, resulting in enhanced migration of a variety of cell types 43. Similarly, cleavage of the laminin-5 β3 subunit has also been attributed to MT1-MMP, corresponding to increased motility of prostate carcinoma cells on the modified substratum 50. Other laminin isoforms including laminin-10, prevalent in the prostate basement membrane and laminin-2/4 found in muscle basement membrane can also be processed by MT1-MMP, regulating invasion and myoblast differentiation, respectively 51, 52.

Endothelial cell MT1-MMP also participates in pericellular fibronolysis as well as regulation of angiogenesis by MT1-MMP-catalyzed collagen cleavage, 48. Using tissues from plasminogen and/or plasminogen activator-deficient mice, invasion of fibrin barriers and neovessel formation occurred in an MT1-MMP-dependent manner, suggesting an alternative fibrinolytic pathway. Biochemical studies supported this observation and showed MT1-MMP solubilization of cross-linked fibrin clots 46. MT1-MMP can also impair clotting by cleavage of fibrinogen as well as via inactivation of Factor XII 47, 53, providing additional evidence for a plasmin-independent impact of MT1-MMP on the fibronlytic system.

The core protein of the heparin sulfate proteoglycan syndecan-1 is also an MT1-MMP substrate, as HT1080 cells (that express endogenous MT1-MMP) spontaneously shed exogenously transfected syndecan-1 54. A syndecan-1 mutant resistant to MT1-MMP cleavage reduced both syndecan-1 shedding and cell migration, supporting a role for MT1-MMP in these processes. MT1-MMP-catalyzed cleavage of aggrecan and perlecan has also been reported 25. The small leucine-rich proteoglycan lumican can function as a tumor suppressor via induction of p21/Waf-1 expression and reduction of colony formation in soft agar. These activities are abolished by MT1-MMP, while, conversely, broad spectrum MMP inhibitors such as BB-94 lead to lumican accumulation and high p21 levels 55.

III. Cleavage of Soluble Proteins by MT1-MMP

a. Intracellular Substrates

Although MT1-MMP is trafficked to the cell surface and processes predominantly extracellular substrates, summarized above, recent studies have identified an intracellular recycling pathway involving the tubulin cytoskeleton, resulting in accumulation of MT1-MMP in the centrosomal compartment 56, 57. Processing of the centrosomal protein pericentrin can be catalyzed by MT1-MMP, leading to mitotic spindle aberrations. Ectopic expression of MT1-MMP in normal mammary epithelium led to enhanced extracellular invasive activity, pericentrin cleavage, and tumor growth in a xenograft model 58, suggesting that MT1-MMP may function in malignant transformation as well as metastasis.

b. Latent Enzymes and Growth Factors

An MT1-MMP-like activity was initially reported as a “plasma membrane-dependent” activator of proMMP-2, catalyzing zymogen activation at the cell surface 59. Cloning of a cDNA encoding an MMP containing a transmembrane domain and ectopic expression of the construct supported this observation, showing enhanced proMMP-2 zymogen activation 6. Purification of a pro-MMP-2 activating activity from plasma membranes showed identity to the newly cloned MT1-MMP and identified a trimeric activation complex comprised of MT1-MMP, proMMP-2 and TIMP-2 [Fig. 1] 60. Since these early reports, numerous investigators have evaluated the biochemistry of trimeric complex formation and the functional consequences of proMMP-2 activation 8. In addition to proMMP-2, both proMMP-13 61 and proMMP-8 62 are MT1-MMP substrates, indicating involvement of this enzyme in multiple zymogen activation pathways. Because active MMP-2, -8, and -13 have been reported to participate in interstitial collagen degradation 22, 63–65, MT1-MMP may modulate collagen turnover through direct cleavage as well as through zymogen activation. Processing of latent growth factors such as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) has also been reported in epithelial cells, neuronal cells 66 and osteoblasts 67. These data suggest that MT1-MMP may indirectly impact cellular functions by altering the pericellular concentration of active growth factors that regulate matrix deposition.

c. Other Secreted Substrates

Secreted mannose-binding lectin (MBL) plays an essential role in innate immunity by recognizing microorganisms and mediating their destruction by complement activation of phagocytosis 68. Several point mutations of the MBL gene predispose patients to infections and diseases. It was shown that mutants of MBL were susceptible to MT1-MMP-catalyzed cleavage at Gly39-Leu40 → Asn80-Met81 sites, homologous to those cleaved in denatured human MBL, suggesting that MT1-MMP may be involved in altering the host response through clearing MBL 69.

Chemokines belong to a large family of structurally related chemoattractant cytokines that modulate leukocyte migration and other host responses during inflammatory processes 70. Chemokine substrates of MT1-MMP include stromal cell-derived factor (SDF-1) 71 and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-3 72. Both substrates were cleaved at position 4–5, releasing a small N-terminal tetrapeptide. SDF-1 cleavage resulted in loss of receptor binding to CXCR-4, functionally manifested as a loss of CD34(+) hematopoietic stem cell chemoattractant activity 71. MMP-cleaved MCP-3 retained CC chemokine receptor binding activity, but was unable to stimulate a chemoattractant response following receptor engagement 72. These data provide a functional link between MT1-MMP activity and modulation of inflammatory and immune responses.

IV. Cleavage of Cell Surface Substrates

a. Autolysis

Expression of active MT1-MMP results in autolytic degradation and generation of a catalytically inactive species on the cell surface [Fig. 1] 15, 73–75. Autolysis is the result of cleavage at G284-G285 in the linker region of MT1-MMP, followed by an additional cleavage at A255-I256 near the conserved methionine turn, rendering the resulting autolysis product catalytically inactive 19, 73. Although lacking the catalytic domain, the 44 kDa transmembrane hemopexin domain-containing autolysis product is retained on the cell surface 15 and inhibits collagenolytic activity, cellular invasion of collagen gels, and tumor formation 76.

b. Adhesion Molecules

Both limited proteolytic processing and ectodomain shedding catalyzed by MT1-MMP have been reported for a variety of membrane-anchored adhesion molecules [Fig. 4]. Integrins are a family of transmembrane receptors for extracellular matrix ligands and are involved in cell adhesion and recognition in a variety of processes including embryogenesis, hemostasis, tissue repair, immune response, cellular motility, and metastatic dissemination of tumor cells 77–80. MT1-MMP has been demonstrated to exhibit integrin convertase activity and participate in an alternative processing of the pro-αv integrin subunit, generating a disulfide-bonded heavy chain and light chains 81. This cleavage facilitated αvβ3-dependent adhesion, contributing to migration of MCF-7 breast cancer cells on vitronectin 82. Other integrin precursors, including pro-α5, were also cleaved by MT1-MMP while pro-α2 was resistant to MT1-MMP processing 83. In the absence of MT1-MMP, expression of αvβ3 resulted in diminished α2β1-mediated collagen binding; however addition of MT1-MMP to these cells restored collagen binding. Based on these results, the authors proposed the interesting conclusion that MT1-MMP-catalyzed αvβ3 processing regulates integrin cross-talk 83.

Fig. 4. MT1-MMP processing of cell surface substrates.

MT1-MMP catalyzes limited proteolytic processing and/or ectodomain shedding of a variety of membrane-anchored molecules including cadherins, integrins, proteoglycans (PG) and PG receptors as well as other surface substrates including LRP, RANKL, semaphoring 4D etc. These cleavages have been shown to regulate diverse cellular processes as summarized above.

Cadherins associate with catenin family proteins and these complexes support cell-cell interactions, cell polarity and cytoskeletal organization 84. Soluble E-cadherin ectodomain has been detected serum, urine and ascites fluids of cancer patients and is frequently associated with development of metastases and poor outcome 85–90 and several metalloproteinases have been identified as cadherin sheddases 91–94. In a kidney ischemia model, increased MT1-MMP expression correlated with processing of both E- and N-cadherin 95. Culturing cells on fibronectin surfaces abrogated the ischemia-induced MT1-MMP expression and cadherin ectodomain shedding. Neutralizing antibodies and shRNA directed against MT1-MMP were used to demonstrate a key role for MT1-MMP in cadherin shedding, thereby implicating MT1-MMP in ischemia-induced acute renal failure.

Other adhesion receptors such as CD44, a hyaluronan receptor, are also processed by MT1-MMP, generating shed ectodomain fragments of various sizes. For example in MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells, MT1-MMP catalyzed shedding of a 70 kDa CD44 ectodomain fragment, resulting in enhanced motility, while a mutant CD44 lacking the MT1-MMP cleavage site was not processed and did not enhance migration 96. Furthermore, transfection of the cleavage-resistant mutant CD44H inhibited motility, suggesting coordinate control of migration by CD44 and MT1-MMP. CD44 ectodomain shedding by MT1-MMP was stimulated by lactate in trabecular meshwork cells, providing a model system in which to evaluate the effects of CD44 shedding in glaucoma 97. An alternative shedding pattern was observed in A375 melanoma cells. In this report, expression of MT1-MMP promoted ADAM-dependent shedding of a 65–70 kDa CD44 ectodomain, while MT1-MMP itself was implicated in release of a smaller 37–40 kDa ectodomain fragment 98. The functional significance of differential CD44 processing and the role of the distinct fragments in cell motility remain under investigation.

c. Other Receptor/Ligand Substrates of MT1-MMP

The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) is a member of a family of cell surface associated endocytic receptors and is essential for the clearance of multiple proteinase ligands by internalization 99, 100, including secreted MMPs. In vitro analyses showed proteolytic processing of the high molecular weight alpha subunit of LRP by recombinant MT1-MMP catalytic domain and a concomitant decrease in cell surface LRP levels in cells co-expressing LRP and MT1-MMP 101. These data suggest that MT1-MMP-catalyzed LRP cleavage may function ultimately in the regulation of proteinase clearance.

Receptor activator of NF-kB ligand (RANKL) is a transmembrane glycoprotein that is an important regulator of osteoclast maturation and function 102. Proteolytic processing by tumor necrosis factor-a convertase (TACE, ADAM-17) generates soluble RANKL that, similar to cell-associated RANKL, supports osteoclast differentiation, as both cell-bound and soluble RANKL bind the RANK receptor on osteoclasts 103. A recent report demonstrated shedding of RANKL by both ADAM-10 and MT1-MMP, generating two distinct products 104. Downregulation of MT1-MMP expression in osteoblasts resulted in enhanced membrane-associated RANKL and promoted osteoclastogenesis. Similarly, osteoblasts from MT1-MMP deficient mice produced reduced levels of soluble RANKL and also displayed enhanced osteoclastogenesis in vivo. These data support a model wherein MT1-MMP-mediated RANKL shedding contributes to downregulation of osteoclastogenesis.

Semaphorin 4D is a membrane bound ligand for the plexin-B1 receptor and participates in axonal guidance in the developing nervous system as well as blood vessel development 105. The membrane-bound ligand is highly expressed in multiple solid tumors including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma 106, suggesting a regulatory role in tumor angiogenesis. It was recently demonstrated that MT1-MMP-catalyzed proteolytic processing of semaphorin 4D from the tumor cell surface is necessary for stimulation of endothelial cells 106, providing a novel mechanistic link between MT1-MMP activity and tumor angiogenesis.

d. Other Cell Surface Substrates

Cell surface tissue transglutaminase mediates the interaction of integrins with fibronectin via direct associations with β1 and β3 integrins and binding to fibronectin, and ultimately promotes integrin-dependent adhesion and spreading of cells 107. It has been demonstrated that MT1-MMP can proteolytically degrade the cell surface transglutaminase into three fragments of approximately 53, 41, and 32 kDa, resulting in decreased adhesion to and migration on fibronectin in glioma and fibrosarcoma cells 108. In contrast, motility on collagen surfaces was enhanced by MT1-MMP cleavage of transglutaminase, suggesting a role for MT1-MMP in regulating matrix-driven motility.

The transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan syndecan-1 is an integral membrane protein that participates in cell proliferation, cell migration and cell-matrix interactions as an extracellular matrix protein receptor. Cleavage of syndecan-1 by MT1-MMP stimulated cell migration in human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells 54. Proteolytic release of the transmembrane mucin MUC-1 in human uterine epithelial cells is absent in MT1-MMP-deficient fibroblasts and, together with co-localization of the proteinase with MUC-1, support a role for MT1-MMP as a MUC-1 sheddase 109. Cleavage of the membrane-anchored proteoglycan betaglycan, that binds transforming growth factor-beta and regulates its cellular availability, is also catalyzed by MT1-MMP 110. Interestingly, both MUC-1 and betaglycan shedding are stimulated by the tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor pervanadate, highlighting a potential role for tyrosine phosphorylation in MT1-MMP regulation 110, 111.

Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) is a membrane associated Ig-domain-containing inducer of MMP activity in surrounding cells 112, 113. Phorbol ester stimulation of HT1080 and A431 cells resulted in shedding of a 22 kDa EMMPRIN fragment 114. The cleavage site was identified in the linker region between the two Ig domains and shedding was blocked by siRNA directed against MT1-MMP. While this cleavage released the functional N-terminal domain of EMMPRIN from the cell surface, the shed 22 kDa fragment retained MMP-inducing activity, suggesting a potential mechanism for dysregulated MMP expression.

V. Conclusion

In the relatively short time since its discovery, it has become well established that the transmembrane proteinase MT1-MMP is involved in the breakdown of extracellular matrix in normal physiological processes, such as tissue remodeling, embryonic development, and reproduction, as well as in disease processes, including arthritis and cancer metastasis. More recently, novel research tools and approaches have identified new substrates and molecular pathways as targets of MT1-MMP proteolysis, highlighting a broader range of substrates than originally anticipated. Many details of MT1-MMP biochemistry and cell biology remain under investigation including key regulatory issues such as transcriptional control, enzyme trafficking, inhibition, and substrate targeting. The diversity of matrix, soluble and cell surface MT1-MMP targets summarized above provide abundant evidence that acquisition of MT1-MMP activity can dramatically alter the pericellular proteome, thereby regulating widely disparate cellular and organismal processes.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gross J, Lapiere CM. Collagenolytic activity in amphibian tissues: a tissue culture assay. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1962 Jun 15;48:1014–1022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.6.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellerbroek SM, Stack MS. Membrane associated matrix metalloproteinases in metastasis. Bioessays. 1999;21(11):940–949. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199911)21:11<940::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellerbroek SM, Stack MS. Regulatory Mechanisms for Proteinase Activity. In: Simons HJSaC., editor. Proteinase and Peptidase Inhibition. Taylor and Francis; 2002. pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werb Z. ECM and cell surface proteolysis: regulating cellular ecology. Cell. 1997;91(4):439–442. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80429-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato H, Takino T, Kinoshita T, et al. Cell surface binding and activation of gelatinase A induced by expression of membrane-type-1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) FEBS Letters. 1996;385(3):238–240. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00389-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato H, Takino T, Okada Y, et al. A matrix metalloproteinase expressed on the surface of invasive tumour cells.[see comment] Nature. 1994;370(6484):61–65. doi: 10.1038/370061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinckerhoff CE, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: a tail of a frog that became a prince. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2002;3(3):207–214. doi: 10.1038/nrm763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itoh Y, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer. Essays in Biochemistry. 2002;38:21–36. doi: 10.1042/bse0380021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seiki M. Membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase: a key enzyme for tumor invasion. Cancer Letters. 2003;194(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zucker S, Pei D, Cao J, Lopez-Otin C. Membrane type-matrix metalloproteinases (MT-MMP) Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 2003;54:1–74. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(03)54004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato H, Kinoshita T, Takino T, Nakayama K, Seiki M. Activation of a recombinant membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) by furin and its interaction with tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-2. FEBS Letters. 1996;393(1):101–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00861-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yana I, Weiss SJ. Regulation of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase activation by proprotein convertases. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2000;11(7):2387–2401. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.7.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Remacle AG, Rozanov DV, Baciu PC, Chekanov AV, Golubkov VS, Strongin AY. The transmembrane domain is essential for the microtubular trafficking of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118(Pt 21):4975–4984. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu YI, Munshi HG, Snipas SJ, Salvesen GS, Fridman R, Stack MS. Activation-Coupled Membrane Type 1 Matrix Metalloproteinase Membrane Trafficking. Biochemical Journal. 2007 doi: 10.1042/BJ20070552. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellerbroek SM, Wu YI, Overall CM, Stack MS. Functional interplay between type I collagen and cell surface matrix metalloproteinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2001 Jul 6;276(27):24833–24842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itoh Y, Ito N, Nagase H, Evans RD, Bird SA, Seiki M. Cell surface collagenolysis requires homodimerization of the membrane-bound collagenase MT1-MMP. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2006;17(12):5390–5399. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osenkowski P, Meroueh SO, Pavel D, Mobashery S, Fridman R. Mutational and structural analyses of the hinge region of membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase and enzyme processing. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(28):26160–26168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osenkowski P, Toth M, Fridman R. Processing, shedding, and endocytosis of membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2004;200(1):2–10. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toth M, Hernandez-Barrantes S, Osenkowski P, et al. Complex pattern of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase shedding. Regulation by autocatalytic cells surface inactivation of active enzyme. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(29):26340–26350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lafleur MA, Mercuri FA, Ruangpanit N, Seiki M, Sato H, Thompson EW. Type I collagen abrogates the clathrin-mediated internalization of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) via the MT1-MMP hemopexin domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(10):6826–6840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513084200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overall CM, Tam E, McQuibban GA, et al. Domain interactions in the gelatinase A.TIMP-2.MT1-MMP activation complex. The ectodomain of the 44-kDa form of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase does not modulate gelatinase A activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(50):39497–39506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tam EM, Moore TR, Butler GS, Overall CM. Characterization of the distinct collagen binding, helicase and cleavage mechanisms of matrix metalloproteinase 2 and 14 (gelatinase A and MT1-MMP): the differential roles of the MMP hemopexin c domains and the MMP-2 fibronectin type II modules in collagen triple helicase activities. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(41):43336–43344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tam EM, Wu YI, Butler GS, Stack MS, Overall CM. Collagen binding properties of the membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) hemopexin C domain. The ectodomain of the 44-kDa autocatalytic product of MT1-MMP inhibits cell invasion by disrupting native type I collagen cleavage. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(41):39005–39014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohuchi E, Imai K, Fujii Y, Sato H, Seiki M, Okada Y. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase digests interstitial collagens and other extracellular matrix macromolecules. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(4):2446–2451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.d’Ortho MP, Will H, Atkinson S, et al. Membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases 1 and 2 exhibit broad-spectrum proteolytic capacities comparable to many matrix metalloproteinases. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1997;250(3):751–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmbeck K, Bianco P, Caterina J, et al. MT1-MMP-deficient mice develop dwarfism, osteopenia, arthritis, and connective tissue disease due to inadequate collagen turnover. Cell. 1999;99(1):81–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Z, Apte SS, Soininen R, et al. Impaired endochondral ossification and angiogenesis in mice deficient in membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase I. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(8):4052–4057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060037197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hotary K, Allen E, Punturieri A, Yana I, Weiss SJ. Regulation of cell invasion and morphogenesis in a three-dimensional type I collagen matrix by membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases 1, 2, and 3. Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;149(6):1309–1323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.6.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonfil RD, Dong Z, Trindade Filho JC, Sabbota A, Osenkowski P, Nabha S, Yamamoto H, Chinni SR, Zhao H, Mobashery S, Vessella RL, Fridman R, Cher ML. Prostate Cancer-Associated Membrane Type 1-Matrix Metalloproteinase. A Pivotal Role in Bone Response and Intraosseous Tumor Growth. Am J Pathol. 2007 Apr 19; doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gavrilovic J, Reynolds JJ, Murphy G. Inhibition of type I collagen film degradation by tumour cells using a specific antibody to collagenase and the specific tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) Cell Biology International Reports. 1985;9(12):1097–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0309-1651(85)80007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itoh Y, Takamura A, Ito N, et al. Homophilic complex formation of MT1-MMP facilitates proMMP-2 activation on the cell surface and promotes tumor cell invasion. EMBO Journal. 2001;20(17):4782–4793. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf K, Muller R, Borgmann S, Brocker EB, Friedl P. Amoeboid shape change and contact guidance: T-lymphocyte crawling through fibrillar collagen is independent of matrix remodeling by MMPs and other proteases. Blood. 2003;102(9):3262–3269. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu YI, Munshi HG, Sen R, et al. Glycosylation broadens the substrate profile of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(9):8278–8289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311870200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hotary KB, Allen ED, Brooks PC, Datta NS, Long MW, Weiss SJ. Membrane type I matrix metalloproteinase usurps tumor growth control imposed by the three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Cell. 2003;114(1):33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chun TH, Hotary KB, Sabeh F, Saltiel AR, Allen ED, Weiss SJ. A pericellular collagenase directs the 3-dimensional development of white adipose tissue.[see comment] Cell. 2006;125(3):577–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmbeck K, Bianco P, Pidoux I, et al. The metalloproteinase MT1-MMP is required for normal development and maintenance of osteocyte processes in bone. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118(Pt 1):147–156. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barbolina MV, Adley BP, Ariztia EV, Liu Y, Stack MS. Microenvironmental Regulation of Membrane Type 1 Matrix Metalloproteinase Activity in Ovarian Carcinoma Cells via Collagen-induced EGR1 Expression. J Biol Chem. 2007 Feb 16;282(7):4924–4931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608428200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellerbroek SM, Wu YI, Stack MS. Type I collagen stabilization of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001 Jun 1;390(1):51–56. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilles C, Polette M, Seiki M, Birembaut P, Thompson EW. Implication of collagen type I-induced membrane-type 1-matrix metalloproteinase expression and matrix metalloproteinase-2 activation in the metastatic progression of breast carcinoma. Laboratory Investigation. 1997;76(5):651–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haas TL, Davis SJ, Madri JA. Three-dimensional type I collagen lattices induce coordinate expression of matrix metalloproteinases MT1-MMP and MMP-2 in microvascular endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(6):3604–3610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haas TL, Stitelman D, Davis SJ, Apte SS, Madri JA. Egr-1 mediates extracellular matrix-driven transcription of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase in endothelium. J Biol Chem. 1999 Aug 6;274(32):22679–22685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tam EM, Morrison CJ, Wu YI, Stack MS, Overall CM. Membrane protease proteomics: Isotope-coded affinity tag MS identification of undescribed MT1-matrix metalloproteinase substrates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(18):6917–6922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305862101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koshikawa N, Giannelli G, Cirulli V, Miyazaki K, Quaranta V. Role of cell surface metalloprotease MT1-MMP in epithelial cell migration over laminin-5.[erratum appears in J Cell Biol 2000 Oct 16;151(2):479] Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;148(3):615–624. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koshikawa N, Schenk S, Moeckel G, et al. Proteolytic processing of laminin-5 by MT1-MMP in tissues and its effects on epithelial cell morphology. FASEB Journal. 2004;18(2):364–366. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0584fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bini A, Itoh Y, Kudryk BJ, Nagase H. Degradation of cross-linked fibrin by matrix metalloproteinase 3 (stromelysin 1): hydrolysis of the gamma Gly 404-Ala 405 peptide bond. Biochemistry. 1996;35(40):13056–13063. doi: 10.1021/bi960730c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bini A, Wu D, Schnuer J, Kudryk BJ. Characterization of stromelysin 1 (MMP-3), matrilysin (MMP-7), and membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) derived fibrin(ogen) fragments D-dimer and D-like monomer: NH2-terminal sequences of late-stage digest fragments. Biochemistry. 1999;38(42):13928–13936. doi: 10.1021/bi991096g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hiller O, Lichte A, Oberpichler A, Kocourek A, Tschesche H. Matrix metalloproteinases collagenase-2, macrophage elastase, collagenase-3, and membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase impair clotting by degradation of fibrinogen and factor XII. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(42):33008–33013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001836200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hiraoka N, Allen E, Apel IJ, Gyetko MR, Weiss SJ. Matrix metalloproteinases regulate neovascularization by acting as pericellular fibrinolysins. Cell. 1998;95(3):365–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hotary KB, Yana I, Sabeh F, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) regulate fibrin-invasive activity via MT1-MMP-dependent and -independent processes. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2002;195(3):295–308. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Udayakumar TS, Chen ML, Bair EL, et al. Membrane type-1-matrix metalloproteinase expressed by prostate carcinoma cells cleaves human laminin-5 beta3 chain and induces cell migration. Cancer Research. 2003;63(9):2292–2299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bair EL, Chen ML, McDaniel K, et al. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloprotease cleaves laminin-10 and promotes prostate cancer cell migration. Neoplasia (New York) 2005;7(4):380–389. doi: 10.1593/neo.04619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohtake Y, Tojo H, Seiki M. Multifunctional roles of MT1-MMP in myofiber formation and morphostatic maintenance of skeletal muscle. Journal of Cell Science. 2006;119(Pt 18):3822–3832. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tschesche H, Lichte A, Hiller O, Oberpichler A, Buttner FH, Bartnik E. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-8, -13, and -14) interact with the clotting system and degrade fibrinogen and factor XII (Hagemann factor) Advances in Experimental Medicine & Biology. 2000;477:217–228. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46826-3_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Endo K, Takino T, Miyamori H, et al. Cleavage of syndecan-1 by membrane type matrix metalloproteinase-1 stimulates cell migration. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(42):40764–40770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y, Aoki T, Mori Y, et al. Cleavage of lumican by membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase-1 abrogates this proteoglycan-mediated suppression of tumor cell colony formation in soft agar. Cancer Research. 2004;64(19):7058–7064. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Golubkov VS, Boyd S, Savinov AY, et al. Membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) exhibits an important intracellular cleavage function and causes chromosome instability. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(26):25079–25086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Golubkov VS, Chekanov AV, Doxsey SJ, Strongin AY. Centrosomal pericentrin is a direct cleavage target of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase in humans but not in mice: potential implications for tumorigenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(51):42237–42241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Golubkov VS, Chekanov AV, Savinov AY, Rozanov DV, Golubkova NV, Strongin AY. Membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase confers aneuploidy and tumorigenicity on mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Research. 2006;66(21):10460–10465. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strongin AY, Marmer BL, Grant GA, Goldberg GI. Plasma membrane-dependent activation of the 72-kDa type IV collagenase is prevented by complex formation with TIMP-2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(19):14033–14039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strongin AY, Collier I, Bannikov G, Marmer BL, Grant GA, Goldberg GI. Mechanism of cell surface activation of 72-kDa type IV collagenase. Isolation of the activated form of the membrane metalloprotease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(10):5331–5338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knauper V, Bailey L, Worley JR, Soloway P, Patterson ML, Murphy G. Cellular activation of proMMP-13 by MT1-MMP depends on the C-terminal domain of MMP-13. FEBS Letters. 2002;532(1–2):127–130. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03654-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holopainen JM, Moilanen JA, Sorsa T, et al. Activation of matrix metalloproteinase-8 by membrane type 1-MMP and their expression in human tears after photorefractive keratectomy. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2003;44(6):2550–2556. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gioia M, Monaco S, Fasciglione GF, Coletti A, Modesti A, Marini S, Coletta M. Characterization of the mechanisms by which gelatinase A, neutrophil collagenase, and membrane-type metalloproteinase MMP-14 recognize collagen I and enzymatically process the two alpha-chains. J Mol Biol. 2007 May 11;368(4):1101–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lauer-Fields JL, Fields GB. Triple-helical peptide analysis of collagenolytic protease activity. Biological Chemistry. 2002;383(7–8):1095–1105. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seftor RE, Seftor EA, Koshikawa N, et al. Cooperative interactions of laminin 5 gamma2 chain, matrix metalloproteinase-2, and membrane type-1-matrix/metalloproteinase are required for mimicry of embryonic vasculogenesis by aggressive melanoma. Cancer Research. 2001;61(17):6322–6327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mu D, Cambier S, Fjellbirkeland L, et al. The integrin alpha(v)beta8 mediates epithelial homeostasis through MT1-MMP-dependent activation of TGF-beta1. Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;157(3):493–507. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karsdal MA, Larsen L, Engsig MT, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-dependent activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta controls the conversion of osteoblasts into osteocytes by blocking osteoblast apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(46):44061–44067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Turner MW. Mannose-binding lectin: the pluripotent molecule of the innate immune system. Immunology Today. 1996;17(11):532–540. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Butler GS, Sim D, Tam E, Devine D, Overall CM. Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) mutants are susceptible to matrix metalloproteinase proteolysis: potential role in human MBL deficiency. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(20):17511–17519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Foxman EF, Campbell JJ, Butcher EC. Multistep navigation and the combinatorial control of leukocyte chemotaxis. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;139(5):1349–1360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McQuibban GA, Butler GS, Gong JH, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase activity inactivates the CXC chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(47):43503–43508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McQuibban GA, Gong JH, Wong JP, Wallace JL, Clark-Lewis I, Overall CM. Matrix metalloproteinase processing of monocyte chemoattractant proteins generates CC chemokine receptor antagonists with anti-inflammatory properties in vivo.[see comment] Blood. 2002;100(4):1160–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hernandez-Barrantes S, Toth M, Bernardo MM, et al. Binding of active (57 kDa) membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) to tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-2 regulates MT1-MMP processing and pro-MMP-2 activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(16):12080–12089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lehti K, Lohi J, Valtanen H, Keski-Oja J. Proteolytic processing of membrane-type-1 matrix metalloproteinase is associated with gelatinase A activation at the cell surface. Biochemical Journal. 1998;334(Pt 2):345–353. doi: 10.1042/bj3340345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stanton H, Gavrilovic J, Atkinson SJ, et al. The activation of ProMMP-2 (gelatinase A) by HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells is promoted by culture on a fibronectin substrate and is concomitant with an increase in processing of MT1-MMP (MMP-14) to a 45 kDa form. Journal of Cell Science. 1998;111(Pt 18):2789–2798. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.18.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nonaka T, Nishibashi K, Itoh Y, Yana I, Seiki M. Competitive disruption of the tumor-promoting function of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase/matrix metalloproteinase-14 in vivo. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2005;4(8):1157–1166. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Danen EH. Integrins: regulators of tissue function and cancer progression. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2005;11(7):881–891. doi: 10.2174/1381612053381756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gassmann P, Enns A, Haier J. Role of tumor cell adhesion and migration in organ-specific metastasis formation. Onkologie. 2004;27(6):577–582. doi: 10.1159/000081343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jin H, Varner J. Integrins: roles in cancer development and as treatment targets. British Journal of Cancer. 2004;90(3):561–565. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuphal S, Bauer R, Bosserhoff AK. Integrin signaling in malignant melanoma. Cancer & Metastasis Reviews. 2005;24(2):195–222. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-1572-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ratnikov BI, Rozanov DV, Postnova TI, et al. An alternative processing of integrin alpha(v) subunit in tumor cells by membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(9):7377–7385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deryugina EI, Ratnikov BI, Postnova TI, Rozanov DV, Strongin AY. Processing of integrin alpha(v) subunit by membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase stimulates migration of breast carcinoma cells on vitronectin and enhances tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(12):9749–9756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baciu PC, Suleiman EA, Deryugina EI, Strongin AY. Membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) processing of pro-alphav integrin regulates crosstalk between alphavbeta3 and alpha2beta1 integrins in breast carcinoma cells. Experimental Cell Research. 2003;291(1):167–175. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weis WI, Nelson WJ. Re-solving the cadherin-catenin-actin conundrum. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(47):35593–35597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600027200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Billion K, Ibrahim H, Mauch C, Niessen CM. Increased soluble E-cadherin in melanoma patients. Skin Pharmacology & Physiology. 2006;19(2):65–70. doi: 10.1159/000091972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chan AO, Chu KM, Lam SK, et al. Early prediction of tumor recurrence after curative resection of gastric carcinoma by measuring soluble E-cadherin. Cancer. 2005;104(4):740–746. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Charalabopoulos K, Gogali A, Dalavaga Y, et al. The clinical significance of soluble E-cadherin in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Experimental Oncology. 2006;28(1):83–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Matsumoto K, Shariat SF, Casella R, Wheeler TM, Slawin KM, Lerner SP. Preoperative plasma soluble E-cadherin predicts metastases to lymph nodes and prognosis in patients undergoing radical cystectomy. Journal of Urology. 2003;170(6 Pt 1):2248–2252. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000094189.93805.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Syrigos KN, Harrington KJ, Karayiannakis AJ, Baibas N, Katirtzoglou N, Roussou P. Circulating soluble E-cadherin levels are of prognostic significance in patients with multiple myeloma. Anticancer Research. 2004;24(3b):2027–2031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wilmanns C, Grossmann J, Steinhauer S, et al. Soluble serum E-cadherin as a marker of tumour progression in colorectal cancer patients. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 2004;21(1):75–78. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000017204.38807.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maretzky T, Reiss K, Ludwig A, et al. ADAM10 mediates E-cadherin shedding and regulates epithelial cell-cell adhesion, migration, and beta-catenin translocation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(26):9182–9187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500918102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Monea S, Jordan BA, Srivastava S, DeSouza S, Ziff EB. Membrane localization of membrane type 5 matrix metalloproteinase by AMPA receptor binding protein and cleavage of cadherins. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(8):2300–2312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3521-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reiss K, Maretzky T, Ludwig A, et al. ADAM10 cleavage of N-cadherin and regulation of cell-cell adhesion and beta-catenin nuclear signalling.[erratum appears in EMBO J. 2005 May 4;24(9):1762] EMBO Journal. 2005;24(4):742–752. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Symowicz J, Adley BP, Gleason KJ, et al. Engagement of collagen-binding integrins promotes matrix metalloproteinase-9-dependent E-cadherin ectodomain shedding in ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Research. 2007;67(5):2030–2039. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Covington MD, Burghardt RC, Parrish AR. Ischemia-induced cleavage of cadherins in NRK cells requires MT1-MMP (MMP-14) American Journal of Physiology - Renal Physiology. 2006;290(1):F43–51. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00179.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kajita M, Itoh Y, Chiba T, et al. Membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase cleaves CD44 and promotes cell migration. Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;153(5):893–904. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Miller AM, Nolan MJ, Choi J, et al. Lactate treatment causes NF-kappaB activation and CD44 shedding in cultured trabecular meshwork cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007;48(4):1615–1621. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nakamura H, Suenaga N, Taniwaki K, et al. Constitutive and induced CD44 shedding by ADAM-like proteases and membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase. Cancer Research. 2004;64(3):876–882. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hussain MM. Structural, biochemical and signaling properties of the low-density lipoprotein receptor gene family. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2001;6:D417–428. doi: 10.2741/hussain1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Strickland DK, Medved L. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP)-mediated clearance of activated blood coagulation co-factors and proteases: clearance mechanism or regulation?[comment] Journal of Thrombosis & Haemostasis. 2006;4(7):1484–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rozanov DV, Hahn-Dantona E, Strickland DK, Strongin AY. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein LRP is regulated by membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) proteolysis in malignant cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(6):4260–4268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hofbauer LC, Heufelder AE. The role of osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand in the pathogenesis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2001;44(2):253–259. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200102)44:2<253::AID-ANR41>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lum L, Wong BR, Josien R, et al. Evidence for a role of a tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha)-converting enzyme-like protease in shedding of TRANCE, a TNF family member involved in osteoclastogenesis and dendritic cell survival. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(19):13613–13618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hikita A, Yana I, Wakeyama H, et al. Negative regulation of osteoclastogenesis by ectodomain shedding of receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(48):36846–36855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Carmeliet P, Tessier-Lavigne M. Common mechanisms of nerve and blood vessel wiring. Nature. 2005;436(7048):193–200. doi: 10.1038/nature03875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Basile JR, Castilho RM, Williams VP, Gutkind JS. Semaphorin 4D provides a link between axon guidance processes and tumor-induced angiogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(24):9017–9022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508825103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Akimov SS, Krylov D, Fleischman LF, Belkin AM. Tissue transglutaminase is an integrin-binding adhesion coreceptor for fibronectin. Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;148(4):825–838. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Belkin AM, Akimov SS, Zaritskaya LS, Ratnikov BI, Deryugina EI, Strongin AY. Matrix-dependent proteolysis of surface transglutaminase by membrane-type metalloproteinase regulates cancer cell adhesion and locomotion. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(21):18415–18422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Thathiah A, Carson DD. MT1-MMP mediates MUC1 shedding independent of TACE/ADAM17. Biochemical Journal. 2004;382(Pt 1):363–373. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Velasco-Loyden G, Arribas J, Lopez-Casillas F. The shedding of betaglycan is regulated by pervanadate and mediated by membrane type matrix metalloprotease-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(9):7721–7733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306499200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Thathiah A, Brayman M, Dharmaraj N, Julian JJ, Lagow EL, Carson DD. Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates MUC1 synthesis and ectodomain release in a human uterine epithelial cell line. Endocrinology. 2004;145(9):4192–4203. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gabison EE, Hoang-Xuan T, Mauviel A, Menashi S. EMMPRIN/CD147, an MMP modulator in cancer, development and tissue repair. Biochimie. 2005;87(3–4):361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nabeshima K, Iwasaki H, Koga K, Hojo H, Suzumiya J, Kikuchi M. Emmprin (basigin/CD147): matrix metalloproteinase modulator and multifunctional cell recognition molecule that plays a critical role in cancer progression. Pathology International. 2006;56(7):359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.01972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Egawa N, Koshikawa N, Tomari T, Nabeshima K, Isobe T, Seiki M. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP/MMP-14) cleaves and releases a 22-kDa extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) fragment from tumor cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(49):37576–37585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]