Abstract

Reduced skeletal loading typically leads to bone loss because bone formation and bone resorption become unbalanced. Hibernation is a natural model of musculoskeletal disuse because hibernating animals greatly reduce weight-bearing activity, and therefore, they would be expected to lose bone. Some evidence suggests that small mammals like ground squirrels, bats, and hamsters do lose bone during hibernation, but the mechanism of bone loss is unclear. In contrast, hibernating bears maintain balanced bone remodeling and preserve bone structure and strength. Differences in the skeletal responses of bears and smaller mammals to hibernation may be due to differences in their hibernation patterns; smaller mammals may excrete calcium liberated from bone during periodic arousals throughout hibernation, leading to progressive bone loss over time, whereas bears may have evolved more sophisticated physiological processes to recycle calcium, prevent hypercalcemia, and maintain bone integrity. Investigating the roles of neural and hormonal control of bear bone metabolism could give valuable insight into translating the mechanisms that prevent disuse-induced bone loss in bears into novel therapies for treating osteoporosis.

Keywords: calcium, bear, recycling, torpor, remodeling

elucidating the mechanisms underlying natural models of physiological adaptation may aid in the development of new therapies for treating human diseases. These models are advantageous in the pursuit of new clinical therapies because they have evolved unique physiological mechanisms that traditional laboratory animal models of human diseases have not. One natural model of interest is hibernation, a strategy employed by animals to survive periods of reduced food availability. Mammalian hibernators reduce many homeostatic processes to conserve metabolic energy when food is scarce. Physiological changes associated with hibernation are drastic; understanding the biological mechanisms that make it possible to survive long periods of decreased heart rate and ventilation, lack of dietary nutrition and water intake, reduced waste excretion, and chronic immobility could lead to the development of improved treatments for human conditions like cardiac failure, hypoxia, renal and digestive disease, and musculoskeletal atrophy. This review describes how hibernation affects bone.

Primary (age-related) osteoporosis is currently a health threat for ∼44 million Americans. Disuse osteoporosis, which is bone loss caused by reduced mechanical loading of the skeleton, causes bone loss in astronauts and is an important clinical problem for patients chronically immobilized due to stroke or spinal cord injury (92, 190). In humans and most animals, disuse leads to compromised bone architecture (62, 116, 117, 163), loss of mineral density (91, 100), reduced bone mechanical properties (91, 117), and consequently, increased risk of bone fracture (92, 185). Interestingly, at least two hibernating species (Ursus americanus and Ursus arctos horribilis) appear resistant to osteoporosis induced by disuse (55, 128, 141). Although bears are physically inactive for ∼6 mo annually, hibernating bear cortical bone is actually less porous and more mineralized than bone from active bears (128). Investigating mechanisms of bone preservation in hibernating bears may, therefore, lead to the development of improved treatments for osteoporosis. It is possible that the metabolic recycling and energy conservation strategies central to hibernation help protect skeletal tissues during disuse. However, some evidence suggests that bears may be unique in this ability, since smaller mammals (which differ from bears in their hibernation patterns) may experience bone loss during hibernation. Initial studies suggest that smaller mammals may demonstrate decreased bone structural properties and mineralization during hibernation, but further work is needed to explore this hypothesis. This paper reviews current knowledge of the effects of hibernation on bone properties in bears and smaller mammals and explores the potential effects of energy conservation and metabolic recycling mechanisms on bone metabolism.

Effects of Disuse on Bone

Bone typically remodels in response to the mechanical loading that it experiences (154). Whereas exercise and overloading increase bone mass (17, 43), disuse causes bone loss (i.e., decreased bone structure and strength) and an increase in the risk of bone fracture (91, 92, 108, 181, 185). Bone is lost during disuse because bone remodeling becomes unbalanced: bone resorption exceeds formation (7, 21, 117, 149, 178, 196, 199, 208). This bone loss is manifest as increased porosity (66, 87, 88, 105, 117, 156), decreased bone structural properties (62, 117, 163), decreased mineralization (91, 102), and decreased bone strength (1, 117, 183). Although both cortical and trabecular bone are affected by mechanical unloading, the larger surface area of trabecular bone makes it more susceptible to changes in remodeling activity. Disuse-induced losses of trabecular architecture (116), mineral density (91), and strength (91) typically exceed losses of those properties in cortical bone (67, 91, 102). Human and animal models of disuse are discussed in detail below, and their effects on bone properties are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relative amounts of cortical (Ct.) and trabecular (Tb.) bone loss in various human and animal models of disuse

| Property | Disuse Model | Skeletal Location | Bone Loss (% change/length of disuse) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humans | ||||

| Ct.Ar | SCI | femur | −34%/5.3 yr | (52) |

| Ct.Th | SCI | femur | −33%/6.2 yr | (52) |

| Ct. bone strength | SF | femur | −3% 1mo | (93) |

| CSMI | SCI | tibia | −26%/14±10 yr | (34) |

| Ct.BMC | SF | femur | −2%/1 mo | (102) |

| Ct. BMD | SCI | femur | −17%/6±4 mo | (95) |

| Tb.BMC | SF | femur | −2%/1 mo | (102) |

| Tb. BMD | BR | calcaneus | −9%/17 wk | (162) |

| Animals | ||||

| Ct.Ar | Turkeys, LI | ulna | −13%/8 wk | (7) |

| Ct.Th | Rats, NX | femur | −9%/8 wk | (86) |

| Ct. bone strength | Dogs, LI | humerus | −12%/16 wk | (91) |

| CSMI | Rats, HS | femur | −15%/4 wk | (62) |

| Por | Turkeys, LI | ulna | +333%/8 wk | (7) |

| Ct. BMD | Dogs, LI | radius | −15%/15 wk | (100) |

| Tb.BMC | Sheep, LI | calcaneus | −26%/12 wk | (168) |

| Tb. BMD | Dogs, LI | radius | −23%/15 wk | (100) |

| Tb. BV/TV | Sheep, LI | calcaneus | −29%/12 wk | (175) |

| Tb. bone strength | Dogs, LI | humerus | −56%/16 wk | (91) |

Bone property abbreviations: Ar, area; Th, thickness; CSMI, cross-sectional moment of inertia; BMC, bone mineral content; BMD, bone mineral density; Por, porosity; BV/TV, bone volume fraction. Disuse model abbreviations: SCI, spinal cord injury; SF, spaceflight; BR, bed rest; LI, limb immobilization; NX, neurectomy; HS, hindlimb suspension. All differences were statistically significant in the respective studies.

Effects of disuse in humans.

Increased bone resorption and/or decreased bone formation can occur during human spaceflight and prolonged human bedrest (21, 169, 208). These changes can be seen histologically and may be reflected in serum markers of bone remodeling. A 120-day bedrest period decreased mineral apposition rate by 26% and osteoid surface by 41% in the human iliac crest (140, 186), and 12 wk of bedrest led to a 120% increase in eroded surface and a 100% increase in osteoclast surface in the human iliac crest (208). During human bedrest, serum levels of carboxyterminal telopeptide of type I collagen (ICTP, marker of bone resorption) increased by ∼20–30% (208), and during human spaceflight, serum levels of crosslinked carboxyterminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX, marker of bone resorption) increased by 40%, whereas serum osteocalcin (OCN, marker of bone formation) levels decreased by ∼7% (22).

Changes in bone remodeling lead to deleterious alterations in bone structure and geometry in humans. Paralysis from spinal cord injury caused progressive loss of lower-limb bone mineral density (BMD) over time, averaging 17% loss in femoral midshaft BMD in the first year after injury and ∼1.6% per year for the next 5 yr thereafter (95). Similarly, spaceflight caused BMD in the human hip to decrease at a rate of 1.2–1.5% per month (102). Long-term spinal cord injury (13–20 yr) decreased both the cross-sectional area and the maximum cross-sectional moment of inertia of the tibial midshaft by 25–38% compared with healthy, age-matched controls (34). Bone loss resulting from disuse leads to a decrease in bone mechanical properties and increase in the risk of bone fracture (92, 185). Fracture rates double compared with healthy controls in the first year following spinal cord injury (185) and are also elevated compared with healthy controls after the onset of stroke (92).

Bone catabolism induced by disuse liberates calcium from the skeleton, and can consequently lead to hypercalcemia and increased calcium excretion (85, 162, 192, 208). For example, urinary calcium excretion increased 39% and fecal calcium excretion increased 20% during 17 wk of bedrest relative to baseline measurements (162). Increased calcium excretion is also seen during 12 wk of bedrest and is accompanied by a 2% increase in serum calcium levels (208).

Effects of disuse in common laboratory animal models.

Bone loss during disuse in small animals like rats and mice can result from decreased bone formation alone (178, 199), or both increased bone resorption and decreased bone formation (149, 196). Immobilization of canine forelimbs increases both bone resorption and bone formation but causes bone loss via unbalanced relative increases in bone resorption over bone formation, increased remodeling space, and possibly because of an abnormally long lag time between resorption and formation (117). Laboratory animal models of disuse, therefore, demonstrate a similar end result: bone resorption exceeds bone formation and bone loss occurs. The imbalance in resorption and formation can be seen histologically. For example, 8 wk of immobilization in turkey ulnae led to a 1.4-fold increase in the density of remodeling sites relative to controls, and the ratio of formation foci to resorption foci of remodeling sites decreased by 68% (7).

The effects of disuse on cortical and cancellous bone have been studied extensively in animal models such as rats (1, 11, 12, 15, 75, 146, 163, 183, 188), mice (2, 6, 90, 159, 164, 165), dogs (87, 88, 91, 100, 116, 117), sheep (158, 175), turkeys (7, 66, 105, 156), and primates (200–202, 207). In dogs, forelimb immobilization (via casting) for 16 wk caused a 25% decrease in cortical BMD of the radius (91). Four weeks of immobilization in turkey ulnae led to a five-fold increase in porous area and a three-fold increase in porous cavity size compared with controls, and 8 wk of immobilization led to a 13% decrease in cortical area (7, 156). Disuse-induced changes in bone composition and structure lead to a decrease in bone mechanical properties. For example, in dogs, 16 wk of forelimb immobilization reduced the maximum load and ultimate stress of the humerus by ∼21% and 12%, respectively (91). Even short periods of disuse can have deleterious consequences on the skeleton. For example, 1–2 wk of hindlimb suspension in male and female rats decreased cortical bone area in the tibial diaphysis by 6–12%, and decreased bone volume fraction in the proximal tibia by 15–54% (33).

It is clear from previous studies that disuse causes cortical and trabecular bone loss in humans and most animals, and thus, it would be expected that reduced physical activity associated with hibernation would cause substantial bone loss and increased calcium excretion in hibernating mammals. This may be true for small mammals (discussed below), but bears do not excrete waste during hibernation, and evidence suggests that hibernating bears are able to prevent disuse-induced bone loss (39, 55, 128, 141).

Hibernation as a model of skeletal disuse.

Hibernation is a natural model of musculoskeletal disuse because physical activity is greatly reduced, probably to conserve metabolic energy. Hibernation lasts ∼5–8 mo in many mammals, and this length of physical inactivity is known to cause bone loss in nonhibernating species (27, 87, 88, 91, 100, 108, 186, 208). Physical activity sharply declines in bears immediately before denning (106), and bears remain in an inactive state during hibernation (135). Most bear dens are too small to permit weight-bearing activity, and bears typically do not emerge from their dens during the hibernation season (L. L. Rogers, personal communication, 2004). Small hibernators are completely inactive during torpid states, but raise body temperature (Tb) and arouse from torpor every 3–25 days during hibernation (59, 115). However, the animals spend most of their time sleeping during these periodic arousals from torpor (32, 107, 176), and arousal periods are short in length (<24 h) relative to the amount of time spent in torpor (59); laboratory animal models have demonstrated that short periods of activity during prolonged disuse are not sufficient to prevent bone loss. For example, daily exercise periods (up to 1.5 h in length) did not prevent losses of bone mechanical properties in the tibia and femur of hindlimb-suspended rats (163). Common examples of disuse that decrease weight-bearing activity include astronauts in microgravity (93, 102, 103, 187), patients subjected to prolonged bedrest (108, 162, 186, 208), and chronic immobilization from stroke and spinal cord injury (34, 35, 51, 60, 89, 92, 95, 112, 130, 148, 185, 190, 205). Laboratory animal models of disuse often focus on the hindlimbs or forelimbs since weight-bearing skeletal locations are most affected by unloading in humans (108, 187). Common laboratory animal models of disuse include hindlimb suspension of rodents (15, 75, 146, 164, 170, 183), limb immobilization by casting (24, 47, 116, 117, 156, 158), and surgical limb immobilization by neurectomy or tenotomy (132, 196, 206). Thus, with regard to weight-bearing activity, hibernation and other laboratory models of disuse are comparable.

It should be noted that both bears and smaller hibernating mammals experience some degree of shivering during hibernation, which may provide a small mechanical stimulus to bone and muscle tissues. Captive grizzly bears exhibit muscle shuddering (<0.2 s of activation every 3–10 s) during hibernation for periods lasting greater than 1 h (120). Bears may shiver to maintain Tb, since more frequent shivering is observed when ambient temperature decreases (B. M. Barnes, personal communication, 2004). Small mammalian hibernators shiver violently during arousal periods between bouts of torpor. For example, hibernating bats shiver for ∼30 min at the onset of an arousal period, which helps raise Tb and metabolic rate (110). It has been hypothesized that shivering may provide a sufficient mechanical stimulus to maintain muscle in hibernating mammals (70, 109); wild black bears only lose 23–29% of muscle strength during hibernation (71, 121), whereas humans are predicted to lose up to 90% of muscle strength during a comparable length of disuse (71). Similarly, captive grizzly bears maintain muscle composition and fiber cross-sectional area during hibernation (77), and small mammals either preserve (109, 189) or experience smaller losses (171, 198) of muscle mass and strength during hibernation than would be expected during disuse in nonhibernating species (reviewed in Ref. 84). It has also been hypothesized that shivering could help preserve bone tissue during hibernation (141). However, small mammals demonstrate bone loss during hibernation despite periodic shivering during arousals (as will be discussed in detail below) (69, 97, 99, 172, 197). Furthermore, since low-magnitude, high-frequency mechanical stimulation is not anabolic for cortical bone (157), but hibernating bears completely prevent cortical bone loss (128), it is likely that the mechanical loading provided by shivering is inadequate for explaining this phenomenon in bears.

Effects of Hibernation on Bones in Small Mammals

Previous studies suggest that small mammals may experience bone loss during hibernation. Evidence demonstrating bone loss during hibernation has been obtained in bats, hamsters, and ground squirrels; osteocyte lacunar size increases in these animals during hibernation (69, 97, 99, 172, 197), cortical bone thickness decreases in hibernating bats and hamsters (97, 99, 172, 197), and bone mineral content progressively decreases during hibernation in bats (20) (Fig. 1). Most previous studies of hibernation-induced bone loss in small hibernating mammals, however, were largely or solely observational rather than quantitative (42, 69, 97, 99, 138, 210), and thus, the conclusions that can be drawn from them are limited. For example, although osteocyte lacunar size has been reported to increase in bats, hamsters, and ground squirrels, only one study on hamsters has quantified lacunar area (172), whereas other studies reported histological images without quantitative measurements (42, 69, 97, 99, 197, 210). Comparisons of hibernating to active counterparts are difficult to interpret as well. For example, although bone mineral content decreases over the course of hibernation in bats, it is 9–24% higher in hibernating bats relative to summer controls (20) (Fig. 2). Similarly, cortical bone thickness is elevated by ∼17% in hamsters that have hibernated for 1 wk relative to nonhibernating controls (172), but after longer periods of hibernation, cortical thickness decreases (Fig. 2). It is unclear whether smaller hibernators employ protective mechanisms to increase bone mass during the prehibernation period to help preserve skeletal integrity during the hibernation season. Furthermore, previous studies of bone properties in small hibernating mammals do not acknowledge or describe the effects of periodic interbout arousals from torpor; it is not known whether the observed bone loss occurred during torpor (i.e., directly in response to disuse) or if it represented a cumulative negative consequence of bone loss during periodic arousal periods throughout the hibernation season.

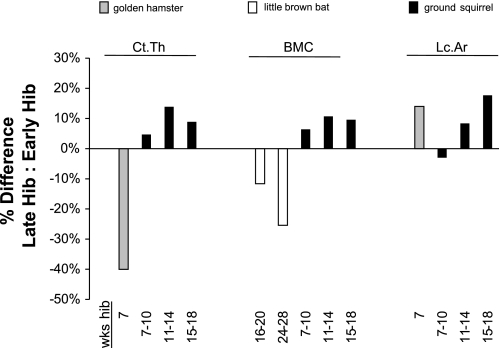

Fig. 1.

Changes in bone properties of small mammals during hibernation. Data are for golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) (172), little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) (20), and 13-lined ground squirrels (Spermophilus tridecemlineatus) (unpublished data). Early hibernation is defined as the earliest timepoint during hibernation when bone properties were quantified and reported. Percentage differences demonstrate the change in bone properties for each species at late timepoints of hibernation relative to early hibernation. A negative percentage difference in cortical thickness (Ct.Th) and bone mineral content (BMC) suggests losses of bone structure and mineralization. For example, golden hamsters decrease cortical bone thickness by ∼40% after 7 wk of hibernation relative to the onset of hibernation. A positive percentage difference in the lacunar area (Lc.Ar) also suggests bone loss (increased bone porosity) over the course of hibernation. Measurements of cortical thickness and BMC in ground squirrels, however, may have been confounded by age-related increases, leading to a positive percentage difference in these properties which could have overshadowed hibernation-induced bone loss.

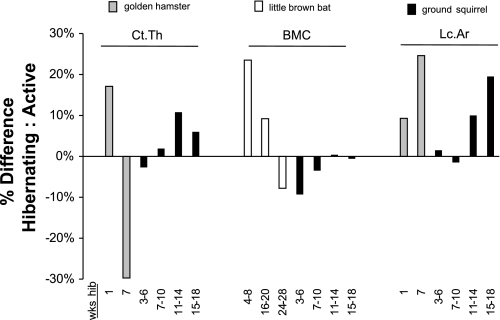

Fig. 2.

Changes in bone properties of hibernating compared with active animals for small hibernators. Data are for golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) (172), little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) (20), and 13-lined ground squirrels (Spermophilus tridecemlineatus) (unpublished data). Percentage differences demonstrate the change in bone properties for hibernating animals of each species relative to active controls for different timepoints in the hibernation season. A negative percentage difference in Ct.Th and bone mineral content (BMC) suggests losses of bone structure and mineralization, as is shown for golden hamsters after 7 wk and little brown bats after 24–28 wk of hibernation. A positive percentage difference in lacunar area (Lc.Ar) also suggests bone loss during hibernation relative to periods of physical activity, as is shown for both hamsters and ground squirrels. However, compared with active animals, BMC is elevated in bats that have hibernated <20 wk, and cortical thickness is elevated in hamsters that have hibernated for 1 wk; it is unclear whether these changes are an adaptive mechanism for hibernation or a confounding effect from another variable.

More comprehensive investigations of the effects of hibernation on bones in small mammalian hibernators are ongoing. In our laboratory, lacunar microstructure, bone mechanical properties (e.g., ultimate stress), geometrical properties (e.g., cortical area), and mineral content have been quantified for femurs from juvenile thirteen-lined ground squirrels (Spermophilus tridecemlineatus) killed during periods of physical activity, hibernation, and after a remobilization period of 4 wk following hibernation (n = 8 active, 37 hibernating, 4 remobilized; unpublished data). These studies suggest that bone loss may occur on a microstructural scale during hibernation; similar to previous studies, lacunar size increased during hibernation (Fig. 3). However, the effects of disuse on cortical bone geometry and strength are less clear. Bone geometrical properties and ash fraction of the femur were not different between juvenile squirrels before, during, or after hibernation (P > 0.20), which is in contrast to the decreased cortical thickness and demineralization reported in hibernating bats and hamsters (20, 97, 99, 172). Similarly, in golden-mantled ground squirrels (Spermophilus lateralis), femoral and tibial bone strength were not different between active controls and squirrels that had hibernated for 8 mo (180). Increasing trends in bone properties like ultimate load, ash fraction, and moments of inertia, which are typically associated with skeletal growth in the femur, were observed over the course of hibernation in juvenile thirteen-lined ground squirrels (P < 0.05, r > 0.40). Ground squirrels may reach adult size with fused long bone epiphyses before their first hibernation period (26, 94, 209), but these bone properties can increase beyond skeletal maturity and may therefore still have been confounded by aging. It is, therefore, difficult to know whether hibernation caused small decreases in bone properties that could have been overshadowed by age-related trends. Furthermore, though osteocyte lacunar expansion was observed similar to previous studies in hibernating mammals, the squirrels did not have access to food during the hibernation period, and lack of dietary calcium can increase average lacunar size in growing animals via abnormal bone matrix formation (166, 167). As such, the biological mechanism responsible for the observed increase in lacunar size (osteocytic osteolysis or malformed bone matrix) cannot presently be determined. Quantitative studies in adult animals are needed to better address the question of cortical bone loss in small hibernating mammals.

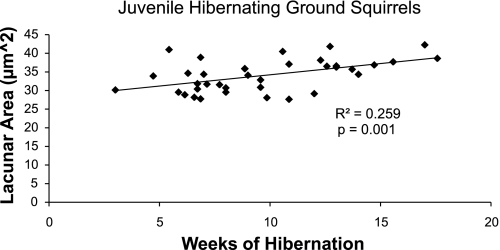

Fig. 3.

Average osteocyte lacunar area was quantified at the femoral midshaft for juvenile (<1 yr old) ground squirrels that had been hibernating for 3–18 wk and was regressed against hibernation length. Osteocyte lacunar size increased over the course of hibernation (P = 0.001). This trend is likely independent of skeletal growth, because lacunar size does not change with age in the femoral midshaft (147).

In summary, there is some evidence to suggest that small hibernators experience disuse-induced bone loss. At present, however, the lack of quantitative data and unclear relationships in bone properties between hibernating and active animals make it difficult to fully characterize the skeletal response of small mammals to hibernation.

Bone Preservation in Hibernating Bears

In contrast with smaller mammals, there is strong evidence to suggest that bears prevent bone loss during hibernation. Studies of serum bone remodeling markers (39–41), histological indices of trabecular and cortical bone turnover (55, 128), and measurements of bone strength and structure (127–129) in hibernating and active bears suggest that bears can maintain balanced bone remodeling during hibernation which prevents disuse-induced bone loss. Bears may therefore provide a unique model of skeletal resistance to disuse osteoporosis. A summary of the effects of hibernation on bone properties in bears is shown in Fig. 4.

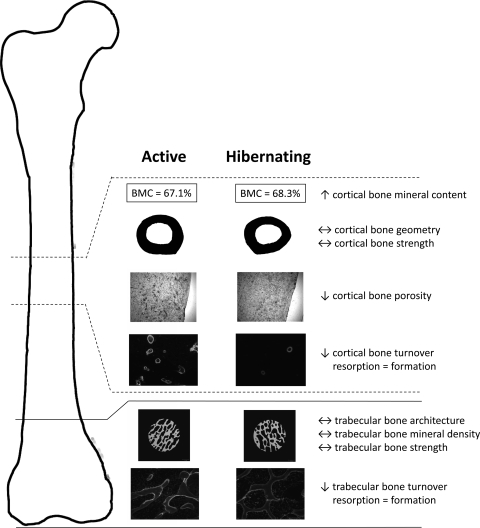

Fig. 4.

Summary of the effects of hibernation on bear cortical and trabecular bone strength, structure, composition, and turnover. Cortical bone properties have been quantified in the femoral midshaft, and trabecular bone properties have been quantified in the distal femoral metaphysis and distal femoral epiphysis (pictured here), as well as in the ilium. In contrast with humans and other animals, bears prevent cortical and trabecular bone loss during disuse. Cortical and trabecular bone remodeling decrease (↓), but bone resorption and bone formation remain balanced in hibernating bears. This likely explains why bone structure (geometry, architecture) and strength are not different (↔) between hibernating and active bears. The decrease in cortical bone turnover probably explains why porosity is decreased and bone mineral content is elevated (↑) in hibernating bears.

Seasonal changes in serum bone remodeling markers in bears.

In the first published study of the effects of hibernation on bear bone, histological analyses of iliac crest biopsies from hibernating and active bears suggested that bear trabecular bone remodeling increases during hibernation (with balanced bone resorption and formation), which helps maintain trabecular bone structure and calcium homeostasis (55). However, small sample sizes (n ≤ 3 bears per season) limited the conclusions that could be drawn from that study. Studies of bone turnover in bears were, therefore, expanded upon by quantifying serum markers of bone remodeling in a larger group of hibernating and active bears. Serum levels of procollagen type I carboxyl-terminal propeptide (PICP, a marker of bone formation) and carboxyterminal telopeptide of type I collagen (ICTP, a marker of bone resorption) represent bone turnover in the entire skeleton and are correlated with histologically measured volume-referent bone formation and resorption rates, respectively (50). PICP and ICTP were quantified from blood samples collected periodically throughout the year from wild black bears (41) and every 10 days in captive black bears during prehibernation, hibernation, and posthibernation seasons (40). These studies suggested that bone resorption increased in hibernating bears, whereas formation markers did not change during hibernation but were elevated upon remobilization after hibernation (40, 41). Thus, our original theory was that bears experience some bone loss during hibernation due to increased resorption, but lost bone could be rapidly recovered by elevating bone formation at the onset of spring remobilization (40, 41). However, more recent analyses of longitudinal data (39) led to the theory that bone loss is prevented during hibernation by maintaining balanced bone resorption and formation (described below).

Bone remodeling markers have recently been quantified in polar bear mothers before and after they have given birth, and therefore before and after hibernation since pregnant female polar bears hibernate for a 3-mo gestational and 3-mo lactation period after birth (114). The serum concentration of the bone resorption marker (ICTP) was higher in polar bears after hibernation compared with nonhibernating bears, and tended to be higher in posthibernation polar bears compared with prehibernation bears. One marker of bone formation (PICP) tended to be lower in posthibernation compared with nonhibernating bears, whereas another marker of bone formation (osteocalcin) was increased in both posthibernation and prehibernation bears compared with nonhibernating bears (114). On the basis of the osteocalcin and ICTP data, it was inferred that polar bears may elevate bone formation before and during hibernation to prevent disuse-induced bone loss (114). However, no direct measures of bone turnover were made during hibernation, and the lack of agreement between formation marker data and a trend for increased bone resorption in posthibernation bears make it difficult to draw conclusions from these data. Furthermore, conclusions in both the black bear and polar bear serum marker studies described above were based on mean concentrations of remodeling markers in each season, not their temporal changes over the course of hibernation. Longitudinal studies of bone turnover markers in hibernating and active black bears throughout the year suggest that both resorption (ICTP) and formation (osteocalcin and PICP) increase over the course of hibernation, but resorption and formation remain balanced which helps bears prevent bone loss during hibernation (39).

A limitation of serum bone remodeling marker data in bears is that serum markers represent global bone turnover, and it is therefore unclear whether all skeletal locations respond similarly to disuse in bears during hibernation. Remodeling markers like ICTP and osteocalcin may accumulate in the serum when renal function is impaired, as occurs in human patients with renal failure (36, 179). Since hibernating bears decrease renal function and do not excrete waste during hibernation, remodeling markers may reflect accumulation rather than bone cell activity. Furthermore, osteocalcin, which is a commonly used bone formation marker, may also act as a hormone in the interaction between bone and adipose tissues, possibly through regulation of adiponectin (45, 111, 113, 150) and may play a role in adipocyte regulation of osteoblast proliferation and differentiation; its exact role and true representation of bone formation activity in hibernating bears is, therefore, unclear. Because of these limitations, more direct measures of bone turnover, structure, mineral content, and strength were made to quantify how hibernation affects bear bone.

Age-related changes in bear cortical bone material properties.

To better understand the effects of hibernation on the bear skeleton, bone structure and strength were quantified to determine the response of discrete skeletal locations (tibial and femoral diaphyses) to disuse in bears. Bone samples were obtained from bears killed during the fall hunting seasons in Michigan (73, 74, 127, 129), and consequently, it was not possible to directly assess the effects of hibernation on bones. Instead, bone properties were analyzed with respect to age. Since bears hibernate annually, age was used as an indicator of the number of annual periods of disuse a bear has experienced. This is of interest because a remobilization period that is 2–3 times longer than the inactive period is typically required to fully recover bone lost during disuse (91, 195), and therefore bears, which hibernate for 6 mo annually, would be expected to lose bone with age due to the annual deficit in recovered bone.

Cortical bone material properties in black bears were quantified using traditional approaches for materials testing (3-point beam bending and tensile tests) on bone coupons from the anterior and medial quadrants of the tibial diaphysis. These studies permitted analyses of cortical bone structure and strength independent of the confounding effects of whole bone geometry (177). Cortical bone-bending strength and ash fraction (a measure of mineral content) in the tibial diaphysis increased with age, and bone tensile strength did not change with age (73, 74). Bone strength and mineralization increased with age at approximately the same rate as in humans of similar relative ages (i.e., age normalized to life span) (31). Interestingly, porosity in the medial quadrant of the tibia tended to decrease with age, contrary to the age-related increase in porosity seen in humans (73, 191). Bears, therefore, did not demonstrate cumulative losses of bone material properties with age despite relatively short remobilization periods following annual hibernation. However, the strength of a whole bone (an indicator of fracture risk) is determined by bone geometrical properties, in addition to material properties. Furthermore, other animal models of disuse show that disuse-induced increases in porosity do not occur uniformly within a whole bone cross section (66). Thus, hibernation-induced changes in bone properties may have been missed in studies on small bone coupons.

Age-related changes in bear whole bone properties.

We began investigating whole bone properties in bears because physical inactivity can cause bone loss in localized regions of the diaphyseal cortex (66, 163), and this bone loss can reduce whole bone mechanical properties (163). For example, 8 wk of immobilization of turkey radii caused a 161% increase in cortical porosity compared with control values, and 58% of this increased porosity was located within the ventral/caudal segment of the cortex (representing only 24% of total cortical area) (66). Similarly, rats subjected to hindlimb suspension for 4 wk demonstrated thinning in the anterior region of the femoral cortex, but not in other areas (163). Since porosity and cortical thickness are correlated with bone mechanical properties (82, 124), regionally focused bone loss may lead to locally weakened regions in the cortex, which reduce whole bone mechanical properties (163). It was important to determine whether hibernation produced localized microstructural or geometrical changes in bone cortices that could impact whole bone mechanical behavior. Whole bone structural and mechanical properties were investigated in the femur because it has a superior length-to-depth ratio compared with the tibia, and it is therefore more appropriate for whole bone 3-point bending tests (177). Also, compared with the tibia, the femur may be more detrimentally affected by disuse (163). Intracortical porosity was quantified by anatomical quadrant (anterior, posterior, medial, lateral) and by radial position (endosteal, midcortical, periosteal) to look for regional variation in porosity with age. Moments of inertia were quantified for several different axes to determine whether annual hibernation led to a redistribution of bone. Bone mechanical properties were determined by three-point bending, and geometrical properties and ash fraction were quantified near the femoral midshaft. Ash fraction and whole bone bending strength increased with age in bears, and porosity did not increase with age, even in bears near the end of their life span (127, 129). There was little variation in intracortical porosity between quadrants or radial position, and all moments of inertia increased with age (127, 129). These data provided further support for the idea that bears do not experience bone loss with aging due to the cumulative effects of hibernation. It was still unclear, however, whether bears prevented bone loss during hibernation or if they lost some bone during hibernation and recovered it during the summer months when they were physically active.

Seasonal changes in bear cortical bone properties.

The direct effects of hibernation on bear skeletal tissues were observed by studying cortical bone turnover in calcein-labeled hibernating and active grizzly bears (n = 4 bears per season) (128) (Table 2). Bears were paired by age and sex and were killed during periods of physical activity or after ∼17 wk of hibernation. This model is an improvement over previous studies of age-related changes in bear bones because it permits direct comparison of bone properties in hibernating and active bears. Therefore, it was possible to determine whether bears completely prevent bone loss during hibernation or whether they lose bone and subsequently recover it at a faster rate than other animals recover from disuse-induced bone loss. Analyses of whole bone structure and strength were completed, as described in Age-related changes in bear whole bone properties, and additionally, static and dynamic histomorphometry were used to quantify bone turnover. Bone geometrical and strength properties were not different between hibernating and active bears, and interestingly, porosity was lower and bone mineral content was higher in hibernating compared with active grizzly bears (128), contrary to the increased porosity and demineralization that accompany disuse in other animals (66, 87, 105) Furthermore, activation frequency of intracortical remodeling was reduced by 75%, and refilling and resorption cavity densities were 55% and 68% lower, respectively, in hibernating grizzly bears. Therefore, these histological studies suggested that bone remodeling activity (both resorption and formation) are decreased, but balanced, in hibernating grizzly bears, which likely explains how bears preserve bone structure and strength during hibernation (128). On the basis of measurements of intracortical activation frequency and remodeling cavity size, the amount of actively remodeling bone in hibernating grizzly bears is only about 25% of the amount of bone that actively remodels in physically active grizzly bears. This is contrary to the increased bone turnover that can lead to bone loss in other animal models of disuse (117). The decrease in cortical bone remodeling during hibernation likely explains why bone mineral content was elevated in the hibernating bears, since older bone is more mineralized than newly remodeled bone. Intracortical porosity was probably lower in the hibernating bears because resorption indices and activation frequency were reduced but normalized formation rates were unchanged, which allowed existing pores to refill despite the decrease in bone turnover.

Table 2.

Hibernation-induced changes in bear cortical and trabecular bone properties

| Bone Property | Ursus arctos % Difference Hib: Active n = 8 | Ursus americanus % Difference Post: Pre n = 65 |

|---|---|---|

| Cortical bone area | −2.2% | −0.3% |

| Cortical bone ultimate stress | +6.9% | −1.8% |

| Cortical bone ash fraction (bone mineral content) | +1.8% * | +0.2% |

| Cortical bone porosity | −30.3% * | −11.7% |

| Intracortical activation frequency | −74.8% * | |

| Refilling cavity density | −55.6% | |

| Resorption cavity density | −66.7% | |

| Trabecular bone volume fraction | −10.0% | |

| Trabecular thickness | +7.7% | |

| Trabecular tissue mineral density | +3.6% | |

| Trabecular osteoid surface | −30.2% | |

| Trabecular eroded surface | −34.4% |

Grizzly and black bears (Ursus arctos and Ursus americanus, respectively) ranged from 1 to 20 yr old and hibernated for 4–6 mo. % Difference (Hib: Active) is the percentage difference for each bone property in hibernating compared to active grizzly bears. Cortical bone properties are reported for the femoral midshaft, and trabecular bone properties are reported for the distal femoral metaphysis (architecture) and ilium (remodeling indices). Similar trends in trabecular architecture were observed in the grizzly bear distal femoral epiphysis and ilium. % Difference Post:Pre is the percentage difference for each bone property in posthibernation compared to prehibernation black bears. % Differences marked with an asterisk

were significantly different between hibernating and active bears at the P < 0.05 level.

More recently, cortical bone geometrical, mineral, porosity, and mechanical properties were quantified in a much larger group of bones from black bears (n = 65) (Table 2). Bears were culled by licensed hunters during the spring and fall hunting seasons in Utah, and one femur was obtained from each bear. The spring bears had remobilized for ∼1–4 wk following 6 mo of hibernation. Despite this small amount of remobilization, this model is an improvement over previous studies because it allows a direct comparison of bone properties in prehibernation and posthibernation bears (fall and spring, respectively) with high statistical power. Furthermore, this amount of remobilization should be insufficient for bone recovery if any bone loss did occur during hibernation (91, 195). Analyses of whole bone structure and strength were completed as described above. Cortical bone strength, geometry, and porosity were not different in prehibernation and posthibernation black bears. (Table 2). The large sample size in this study provided high statistical power (>90% for most properties) and corroborated our findings on grizzly bears that femoral cortical bone is preserved during hibernation. These results were also consistent with a previous study, which found that cortical bone area is not different between fall and spring black bear forelimbs (141). Taken together, these studies provide strong evidence that hibernating bears prevent disuse-induced cortical bone loss in femoral diaphyses.

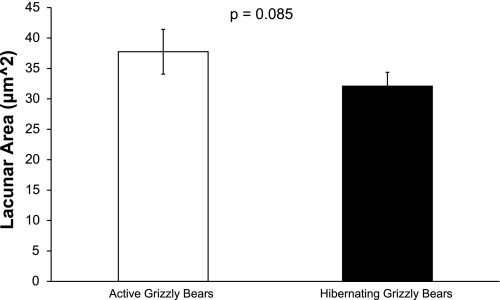

Cortical bone lacunar microstructure has recently been quantified in hibernating and active bears so the effects of hibernation on skeletal structure can be more directly compared between bears and smaller mammals. Lacunar size and lacunar porosity were quantified in hibernating and active grizzly bears that were paired by age and sex. Compared with active bears, lacunar porosity was 26% lower, and lacunar size was 15% lower in bears that had hibernated for ∼17 wk (Fig. 3). This is opposite to the increased lacunar size that has been observed in smaller hibernating animals (69, 97, 99, 172). Hibernating bears, therefore, appear to prevent bone loss on both microstructural and macrostructural levels.

Seasonal changes in bear trabecular bone properties.

The effects of hibernation on trabecular bone in bears are also of interest because trabecular bone, because of its greater surface area, responds to disuse more rapidly (27, 187) and shows greater losses than cortical bone for a given period of inactivity (67, 91, 102). Early studies suggested that bears maintain trabecular bone in the ilium during hibernation (55). More recently, trabecular bone architecture in the distal radius was quantified and compared between black bears killed in the fall (prehibernation) and spring (posthibernation) black bears. There were no differences in trabecular bone mineral content, trabecular thickness, or trabecular bone volume fraction (P > 0.2) between fall and spring bears (141). These results were confirmed in the distal femoral metaphysis, distal femoral epiphysis, and ilium of hibernating and active grizzly bears (125); there were no differences in trabecular bone architecture or mineral density in any of these skeletal locations (Table 2). Trabecular remodeling indices were quantified in the ilium of hibernating and active grizzly bears. Interestingly, trabecular bone turnover was decreased in hibernating bears, but bone formation (osteoid surface) and resorption (eroded surface) indices were decreased by approximately the same amount, suggesting that bone remodeling remains balanced in bear trabecular bone during hibernation (Table 2). These results are comparable to the effects of hibernation on cortical bone in grizzly bears, but opposite to what occurs in other animal models of disuse (116, 196). However, a limitation of these studies is their low sample size (n = 4 bears per season). Further studies in a larger population of bears are needed to determine the effects of hibernation on bear trabecular bone. Additionally, other skeletal sites should be investigated to determine whether the response of bear trabecular bone to hibernation is uniform throughout the skeleton.

In summary, bone remodeling is decreased, but bone formation and bone resorption remain balanced in hibernating bears. This leads to increased cortical bone mineral content, decreased intracortical porosity, preserved trabecular bone architecture and cortical bone geometry, and maintenance of bone strength during hibernation, which is opposite to what occurs in humans and other animals during disuse. Skeletal preservation during hibernation explains why bears do not demonstrate cortical bone loss with age despite experiencing annual periods of disuse with limited remobilization.

Effects of Seasonal Dormancy on Bone in Nonmammalian Vertebrates

There is a paucity of data on the effects of hibernation and estivation (metabolic depression during dry seasons) on bone in nonmammalian species. Osteocyte lacunar area increases in snakes during dormancy in winter months, and this increase is accompanied by an area of demineralization surrounding the osteocyte lacunae (5). This response is similar to the skeletal response, which leads to bone loss, reported for small hibernating mammals (69, 97, 99, 197). In contrast, estivating frogs maintain bone-bending strength, cross-sectional area, and moment of inertia (83). Additionally, bone loss on the microscale (i.e., osteocytic osteolysis) was not observed in estivating frogs, in contrast to the increased osteocyte lacunar area observed in small hibernating mammals (97, 99, 172); however, quantitative measurements of osteocyte lacunar area were not made in the estivating frogs. At present, it is unknown whether all seasonally dormant vertebrates are able to preserve skeletal structure and what metabolic mechanisms or endocrinological changes may explain the differences in the skeletal response of snakes to hibernation and frogs to estivation.

Hibernation Patterns in Relation to Bone Remodeling

The available data suggest there are differences in the skeletal responses of bears and smaller mammals to hibernation. Small mammals may lose bone during hibernation (Figs. 1–3), whereas hibernating bears appear to completely prevent bone loss (Table 2, Figs. 4 and 5). This disparity may be related to differences in hibernation patterns between bears and small hibernators. Compared with bears, smaller mammals experience much greater relative reductions in physiological processes like metabolic rate (23, 63, 79, 193), heart rate (56, 203, 204), and Tb (49, 56–58, 76, 194) during torpor bouts. Body temperature in small hibernating mammals can fall by 30°C or more, with minimum Tbs typically between 0 and 10°C in most species (63). However, small mammalian hibernators arouse periodically from torpor every 3–25 days due to intense bursts of metabolism that raise Tb to near-normal levels and cause resumption of many metabolic and physiological processes (23, 59, 78, 115). In contrast, the body temperature of hibernating bears remains above 30°C throughout the denning season, and distinct arousals back to 37°C do not occur (134). Bears probably do not demonstrate abrupt arousal periods during hibernation because they can maintain consistent and relatively high Tbs throughout the winter. Differences in the seasonal maintenance of Tb may factor into the dissimilar bone responses of bears compared with smaller mammals during hibernation. Furthermore, although renal function is reduced during torpor in both bears and small mammals (19, 81, 204), small mammals resume renal function and excrete waste during interbout arousals (143), whereas hibernating bears do not excrete waste during the hibernation season (56, 135). Therefore, bears must employ more sophisticated recycling mechanisms to prevent toxic buildup of molecules that are normally excreted, like urea and calcium, whereas these molecules can be periodically excreted in smaller hibernating mammals. As will be discussed below, the need to maintain homeostatic calcium levels may explain some of the disparate effects of hibernation on bone properties between bears and smaller mammals.

Fig. 5.

Average osteocyte lacunar area was quantified at the femoral midshaft for age- and sex-matched hibernating and active grizzly bears (n = 4 per season). There was a trend for lower average osteocyte lacunar area in hibernating grizzly bears (P = 0.085).

Calcium Recycling and Hibernation-Induced Bone Loss

Small mammals excrete waste, which contains calcium, during interbout arousals from torpor (20, 143–145, 161). This calcium may be liberated from bone as a direct response to reduced skeletal loading during hibernation. Alternatively, small mammals may excrete calcium as a byproduct from the resumption of metabolic processes during interbout arousal periods from torpor. If the latter is true, serum calcium levels would need to be replenished to maintain homeostasis, likely by stimulating the release of calcium from the skeleton. This could lead to progressive bone loss over time as a result of the cumulative effects of multiple arousal periods over the hibernation season.

Since osteoclastic measures do not substantially increase in small hibernating mammals (42, 138, 172, 197), hibernation-induced bone loss in small mammals has classically been attributed to osteocyte activity rather than unbalanced bone remodeling by osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Osteocytic osteolysis is a process by which osteocytes demineralize their perilacunar matrix tissue (30, 96, 174). Although the osteolytic capacity of osteocytes has been questioned in the past (16, 123, 142), recent literature supports the ability of osteocytes to modify their local microenvironment to aid in mineral homeostasis (30, 101, 174). Osteocytes have receptors for parathyroid hormone (PTH) (37, 184), the primary regulator of serum calcium levels, and osteocytes can produce acid phosphatase, a bone demineralization agent, in response to resorptive signals from continuous PTH administration, which may cause lacunar enlargement (174). This suggests that osteocytes can sense and respond to signals aimed at serum calcium maintenance. The abundance of osteocytes in bone tissue relative to other bone cells, coupled with the large amount of lacunar surface area readily available to osteocytes, suggests that calcium mobilization by osteocytes could require less metabolic energy to maintain calcium homeostasis compared with energy required for increased bone turnover by osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Calcium mobilization via osteocytic osteolysis could therefore be consistent with mechanisms of energy conservation and the bone loss previously observed in small hibernating mammals; small mammals may conserve metabolic energy by using osteocytic perilacunar bone matrix modifications to maintain serum calcium levels by replacing excreted calcium. In support of this hypothesis, histological evidence of osteocytic osteolysis associated with hibernation can be prevented by injections of calcitonin, a hormone that prevents osteocytic osteolysis and hypercalcemia caused by continuous PTH administration in vivo (53), although this procedure was associated with high mortality rates in hibernating bats (97). The authors of that study speculated that the high mortality rates following calcitonin injections could be due to an imbalance in serum calcium levels, caused by an exogenous suppression of osteocytic osteolysis that affected calcium homeostasis, but plasma calcium was not directly measured. The effects of hibernation on serum calcium levels are difficult to discern because considerable variation is reported in the literature. Compared with active controls, serum calcium is elevated in hibernating hamsters (54), has been reported to either increase (20, 99) or decrease (151, 152) in hibernating little brown bats, and remains constant in hibernating ground squirrels during 6 days of continuous torpor and during extended hibernation interrupted by periodic arousals (144). Variation between studies is likely influenced by factors like species differences, food availability, hibernation length, and sampling time relative to interbout arousal periods.

In contrast with small hibernators, bears do not excrete waste for ∼6 mo annually (56, 135). Consequently, bears must recycle catabolic products (e.g., urea and calcium) to maintain homeostasis. However, like smaller mammals, the demand for metabolic energy can be decreased if bone formation and resorption processes are reduced during hibernation, as occurs with other physiological processes like heart rate, kidney function, and metabolic rate (19, 56, 79, 193). Therefore, from the standpoints of both energy conservation and calcium homeostasis, decreased bone remodeling (with balanced resorption and formation) seem beneficial for hibernating bears. Previous research supports the idea that bears experience decreased, but balanced, bone remodeling during hibernation, which helps them to preserve bone structure and strength (128) and maintain constant serum calcium levels (55). PTH is the primary regulator of serum calcium levels, and serum PTH levels are correlated with the serum bone formation marker osteocalcin in hibernating and active bears (39). It is possible that increased levels of PTH cause increased renal reabsorption of calcium, facilitating the recycling of mineral back into bone (39).

Potential Roles of Neural and Hormonal Regulation of Bear Bone Metabolism

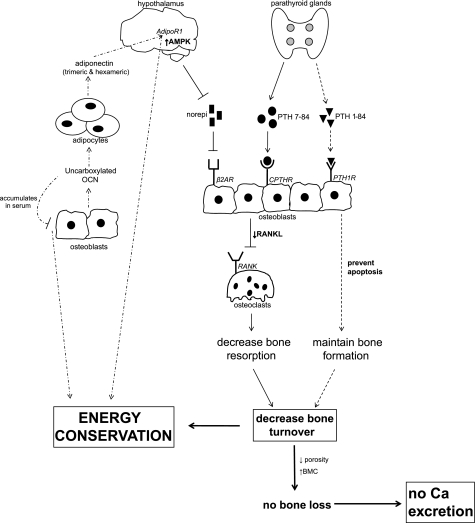

The mechanisms by which bears prevent bone loss during hibernation are likely influenced by hypothalamic control. The hypothalamus controls the downregulation of energy-expensive processes during hibernation, and since bone remodeling processes (which are energy expensive) are decreased in hibernating bears, it is possible that hypothalamic control drives this adaptation. It is interesting to note that the relative decreases in bone remodeling and other physiological processes by hibernating bears are comparable, suggesting a possible role for hypothalamic control of bone remodeling during hibernation. For example, heart rate and metabolic rate in hibernating black bears can be reduced by ∼75–80% compared with active bears (10, 56, 194), similar to the 75% decrease in intracortical activation frequency observed in hibernating grizzly bears (128). A possible mechanism for hypothalamic control of bone remodeling is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Possible mechanism for hypothalamic regulation of bone remodeling and energy conservation in bears. Decreased norepinephrine and increased PTH 7-84 could signal for decreased osteoblast expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL), thus inhibiting osteoclast differentiation and decreasing bone resorption. Concomitantly, PTH 1-84 could maintain osteoblast viability and prevent disuse-induced osteoblast apoptosis, maintaining bone formation at the onset of hibernation. Osteoblasts could then continue synthesizing carboxylated and uncarboxylated osteocalcin, the latter of which could act on adipocytes to trigger the release of trimeric and hexameric forms of adiponectin. These forms of adiponectin, acting through the AdipoR1 receptor in the hypothalamus, could increase AMPK and contribute to the process of energy conservation during hibernation. Increased serum osteocalcin could serve as a negative regulator of osteoblast function, decreasing bone formation during hibernation and thus contributing to the conservation of energy.

The hypothalamus is already known to play a key role in the central regulation of bone remodeling. Leptin, a hormone that affects appetite, body weight, and reproduction (3, 4, 61), can affect osteoblast function through receptor activation in the hypothalamus; leptin signaling from adipose tissues is processed and relayed by the hypothalamus, resulting in decreased osteoblast function. Molecular machinery thus exists to exert hypothalamic control over bone-remodeling processes, and it is possible that hypothalamic regulation contributes to the decrease in bone remodeling, which helps preserve skeletal structure, in hibernating bears. Serum leptin concentration is not different in hibernating compared with prehibernation bears (39), but leptin's effects on osteoblasts are mediated via the sympathetic nervous system and activation of the adrenergic receptor β2AR on osteoblasts by norepinephrine (48). Mice lacking β2AR have high bone mass (44, 173), and osteoblasts from mice lacking β2AR show decreased expression of RANKL, a factor that regulates osteoblast-mediated osteoclast differentiation (48). Norepinephrine may also be involved in the central regulation of hibernation (13, 64, 65). We found that serum norepinephrine decreases in hibernating bears compared with prehibernation levels (P = 0.006, unpublished data). Since norepinephrine has a predominantly catabolic effect on bone, the decrease in norepinephrine during hibernation could explain the decrease in bone turnover and prevention of bone loss observed in hibernating grizzly bears (128).

Osteocalcin may also play a role in seasonal regulation of bone turnover in bears. Osteocalcin is the most abundant noncollagenous protein found in bone matrix, and is a commonly used marker of bone formation, but uncarboxylated osteocalcin can also act as a hormone in the interaction between bone and adipose tissues, possibly through regulation of adiponectin. Osteocalcin can increase adiponectin expression in vivo and in vitro, and mice lacking osteocalcin have decreased serum levels and expression of adiponectin (111). This is of interest because serum adiponectin levels are inversely correlated with metabolic rate, and trimeric and hexameric forms of adiponectin can act through the hypothalamus to facilitate energy conservation during times of starvation (98). Adiponectin increases AMPK activity in the hypothalamus, leading to decreased oxygen consumption and energy conservation (98). Increased osteocalcin in bear serum during hibernation (39) could, therefore, play a role in energy conservation by hibernating bears.

Osteocalcin can accumulate in the serum when renal function is impaired, as occurs in human patients with renal failure (36, 179); a similar phenomenon may occur in bears since glomerular filtration rate decreases and waste excretion ceases in hibernating bears (19, 56). Interestingly, osteocalcin may have an inhibitory effect on the activity of mature osteoblasts, since bone formation is increased but osteoblast number is not changed in osteocalcin-deficient mice (45). In bears, this mechanism could contribute to energy conservation, and it could partly explain why bone formation is decreased (in balance with bone resorption) in hibernating grizzly bears (128). Further studies are needed to determine whether bone turnover is reduced in bears as a consequence of the hypothalamic-regulated global reduction in metabolism during hibernation and to elucidate the relative roles of factors like osteocalcin, norepinephrine, adiponectin, and leptin.

Parathyroid hormone (PTH), the primary regulator of serum calcium levels, has also been implicated in the mechanism by which bears recycle calcium and maintain balanced bone remodeling (39, 128). PTH levels are positively correlated with osteocalcin (a marker of bone formation) in hibernating and active bears (39). Bear PTH has antiapoptotic effects on osteoblastic cells in vitro (126); it is possible that bear PTH 1-84 acts through the PTH1 receptor on osteoblasts to prevent the increased apoptosis and decreased bone formation rates normally associated with disuse (2, 46, 196). Increased levels of PTH in bears could cause increased renal reabsorption of calcium, facilitating the recycling of mineral back into the bone by maintaining bone formation in balance with bone resorption (39). This could contribute to the preservation of trabecular and cortical bone properties like mineral content and porosity that has been observed in hibernating bears (55, 128, 141). A biological mechanism involving bear PTH may, therefore, play a role in the ability of bears to maintain balanced bone remodeling during hibernation. However, the exact role of PTH in hibernating bears is unclear. It is possible that the measured concentrations of PTH in bears reflect large, C-terminal fragments of the hormone (C-PTH), rather than the full 84 amino acid hormone, since a second-generation PTH assay (which measures 1-84, 7-84, and 11-84 PTH) was used in these bear serum analyses (39). C-PTH fragments are usually cleared by the kidneys, but accumulate when renal function is decreased [e.g., during renal failure in humans (18, 137)]. Because bears decrease renal function and do not urinate during hibernation (19, 56, 135), it is possible that C-PTH fragments accumulate in hibernating bears. C-PTH fragments, acting through CPTH receptors on osteoblasts and osteocytes, have antiresorptive effects on bone and can decrease serum calcium levels (38, 104, 136) and may contribute to the development of adynamic (low bone turnover) bone disease in humans (131). Therefore, increased C-PTH levels could contribute to the decreases in intracortical turnover and bone resorption indices observed in hibernating grizzly bears (128). Further studies to elucidate the possible contribution of both whole and C-terminal fragments of PTH to the mechanism of skeletal preservation in bears are of interest.

Translating Hibernation-Related Bone Preservation Mechanisms to Treating Human Osteoporosis

Understanding the mechanism which prevents disuse-induced bone loss in bears could lead to improved treatments for osteoporosis. Currently, oral bisphosphonates are the most prescribed pharmaceutical therapy for osteoporosis. Clinically prescribed nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates like alendronate, ibandronate, and risedronate inhibit farnesyl diphosphate synthase (14, 182), preventing GTPase prenylation and decreasing mature osteoclast function (28, 29, 68). This reduces bone resorption and slows bone turnover, allowing unenhanced bone formation processes to slowly restore bone. Although bisphosphonates are effective antiresorptive therapies, they are not capable of directly stimulating bone formation. Recombinant human parathyroid hormone (rhPTH 1-34: Forteo) is currently the only anabolic therapy approved for treatment of osteoporosis. Daily injection of rhPTH produces larger increases in spinal bone mineral density in a shorter amount of time, resulting in greater reduction of bone fracture risk, compared with usage of oral bisphosphonates (25, 72, 119, 133). However, rhPTH may not be able to completely restore lost bone; it has been suggested that men and women can lose between 20 and 30% of cortical and cancellous bone as a result of age-related osteoporosis (153, 160), but only 8–10% is recovered using rhPTH during suggested treatment regimens (80, 133, 139). Thus, there exists a clinical need for improved osteoporosis treatments.

We sequenced bear PTH 1-84 and found nine amino acid differences compared with the sequence of human PTH 1-84. Previous work suggests that exogenous PTH from different species (with differences in their amino acid sequence) can vary in anabolic potential. For example, ovariectomized rats demonstrated a 25% greater bone formation response to daily 25 μg/kg injections of bovine PTH 1-34 than to rat PTH 1-34 (five amino acid sequence differences), resulting in a 37% greater increase in bone volume fraction during treatment (118). Thus, there exists the possibility that the amino acid substitutions in bear PTH cause it to elicit a greater bone formation response compared with human PTH. In support of this hypothesis, we found that bear PTH 1-34 decreases proapoptotic signaling in osteoblasts more than human PTH 1-34 (126).

Other candidates for clinical therapies may emerge from studies of seasonal changes in bear hormone levels and the central control of bone remodeling in hibernating bears. Neuropeptides like neuropeptide Y (NPY) and cocaine amphetamine regulated transcript (CART) are regulated by the central effects of leptin and could possibly contribute to the observed bone-remodeling processes in hibernating bears. NPY can act through Y2 receptor in the hypothalamus and cause decreased bone mass by reducing differentiation of osteoblast progenitor cells (122), and mice deficient in the Y2 receptor demonstrate increased cortical bone mineral density (8). Mice lacking CART have low bone mass and upregulated expression of RANKL but demonstrate normal rates of bone formation (48). Thus CART may decrease bone resorption without affecting bone formation, similar to how grizzly bears demonstrate decreased cortical bone turnover with unchanged normalized mineral apposition rates (128). Exploring neural and hormonal control of bone metabolism during hibernation could give valuable insight into translating the mechanisms that prevent disuse-induced bone loss in bears to novel therapies for treating osteoporosis.

In conclusion, hibernating mammals provide a natural animal model of physiological adaptations to musculoskeletal disuse. The mechanisms by which bears prevent disuse-induced bone loss are likely interrelated with their ability to maintain calcium homeostasis, prevent muscle atrophy, and avoid the negative consequences of renal failure, while not excreting waste during hibernation. For example, when bears decrease renal output during hibernation, calcium released by bone resorption may be recycled back into the skeleton via renal reabsorption and the maintenance of bone formation to maintain homeostatic serum calcium levels. These and other areas of the bear's integrated response to hibernation warrant further study. Elucidating the mechanisms by which bears prevent bone loss during disuse may aid in the development of new therapies for human osteoporosis.

GRANTS

This publication was made possible by Grant AR050420 from National Institutes of Health. Additional funding was received from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Danielle Stoll, Emily Mantila, and Bryna Fahrner for collection of the ground squirrel histological data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abram AC, Keller TS, Spengler DM. The effects of simulated weightlessness on bone biomechanical and biochemical properties in the maturing rat. J Biomech 21: 755–767, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguirre JI, Plotkin LI, Stewart SA, Weinstein RS, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC, Bellido T. Osteocyte apoptosis is induced by weightlessness in mice and precedes osteoclast recruitment and bone loss. J Bone Miner Res 21: 605–615, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahima RS, Dushay J, Flier SN, Prabakaran D, Flier JS. Leptin accelerates the onset of puberty in normal female mice. J Clin Invest 99: 391–395, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahima RS, Prabakaran D, Mantzoros C, Qu D, Lowell B, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS. Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature 382: 250–252, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alcobendas M, Baud CA, Castanet J. Structural changes of the periosteocytic area in Vipera aspis (L.) (Ophidia, Viperidae) bone tissue in various physiological conditions. Calcif Tissue Int 49: 53–57, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amblard D, Lafage-Proust MH, Laib A, Thomas T, Ruegsegger P, Alexandre C, Vico L. Tail suspension induces bone loss in skeletally mature mice in the C57BL/6J strain but not in the C3H/HeJ strain. J Bone Miner Res 18: 561–569, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bain SD, Rubin CT. Metabolic modulation of disuse osteopenia: endocrine-dependent site specificity of bone remodeling. J Bone Miner Res 5: 1069–1075, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldock PA, Allison S, McDonald MM, Sainsbury A, Enriquez RF, Little DG, Eisman JA, Gardiner EM, Herzog H. Hypothalamic regulation of cortical bone mass: opposing activity of Y2 receptor and leptin pathways. J Bone Miner Res 21: 1600–1607, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes BM, Toien O, Edgar DM, Grahn D, Heller C. Comparison of the hibernation phenotype in ground squirrels and bears. In: Life in the Cold: Eleventh International Hibernation Symposium, 2000, p. 11.

- 11.Barou O, Lafage-Proust MH, Martel C, Thomas T, Tirode F, Laroche N, Barbier A, Alexandre C, Vico L. Bisphosphonate effects in rat unloaded hindlimb bone loss model: three-dimensional microcomputed tomographic, histomorphometric, and densitometric analyses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291: 321–328, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barou O, Valentin D, Vico L, Tirode C, Barbier A, Alexandre C, and Lafage-Proust M. H. High-resolution three-dimensional micro-computed tomography detects bone loss and changes in trabecular architecture early: comparison with DEXA and bone histomorphometry in a rat model of disuse osteoporosis. Invest Radiol 37: 40–46, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beckman AL, Satinoff E. Arousal from hibernation by intrahypothalamic injections of biogenic amines in ground squirrels. Am J Physiol 222: 875–879, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergstrom JD, Bostedor RG, Masarachia PJ, Reszka AA, Rodan G. Alendronate is a specific, nanomolar inhibitor of farnesyl diphosphate synthase. Arch Biochem Biophys 373: 231–241, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloomfield SA, Allen MR, Hogan HA, Delp MD. Site- and compartment-specific changes in bone with hindlimb unloading in mature adult rats. Bone 31: 149–157, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyde A, Jones SJ. Early scanning electron microscopic studies of hard tissue resorption: their relation to current concepts reviewed. Scanning Microsc 1: 369–381, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brodt MD, Ellis CB, Silva MJ. Growing C57BL/6 mice increase whole bone mechanical properties by increasing geometric and material properties. J Bone Miner Res 14: 2159–2166, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brossard JH, Cloutier M, Roy L, Lepage R, Gascon-Barre M, D'Amour P. Accumulation of a non-(1-84) molecular form of parathyroid hormone (PTH) detected by intact PTH assay in renal failure: importance in the interpretation of PTH values. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81: 3923–3929, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown DC, Mulhausen RO, Andrew DJ, Seal US. Renal function in anesthetized dormant and active bears. Am J Physiol 220: 293–298, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruce DS, Wiebers JE. Calcium and phosphate levels in bats (Myotis lucifugus) as function of season and activity. Experientia 26: 625–627, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caillot-Augusseau A, Lafage-Proust MH, Soler C, Pernod J, Dubois F, Alexandre C. Bone formation and resorption biological markers in cosmonauts during and after a 180-day space flight (Euromir 95). Clin Chem 44: 578–585, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caillot-Augusseau A, Vico L, Heer M, Voroviev D, Souberbielle JC, Zitterman A, Alexandre C, and Lafage-Proust M. H. Space flight is associated with rapid decreases of undercarboxylated osteocalcin and increases of markers of bone resorption without changes in their circadian variation: observations in two cosmonauts. Clin Chem 46: 1136–1143, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carey HV, Andrews MT, Martin SL. Mammalian hibernation: cellular and molecular responses to depressed metabolism and low temperature. Physiol Rev 83: 1153–1181, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavanagh PR, Licata AA, Rice AJ. Exercise and pharmacological countermeasures for bone loss during long-duration space flight. Gravit Space Biol Bull 18: 39–58, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chesnut IC, Skag A, Christiansen C, Recker R, Stakkestad JA, Hoiseth A, Felsenberg D, Huss H, Gilbride J, Schimmer RC, Delmas PD. Effects of oral ibandronate administered daily or intermittently on fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 19: 1241–1249, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark TW, Skryja DD. Postnatal development and growth of the Golden-Mantled ground squirrel, Spermophilus lateralis lateralis. J Mammal 50: 627–629, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collet P, Uebelhart D, Vico L, Moro L, Hartmann D, Roth M, Alexandre C. Effects of 1- and 6-month spaceflight on bone mass and biochemistry in two humans. Bone 20: 547–551, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coxon FP, Helfrich MH, Van't Hof R, Sebti S, Ralston SH, Hamilton A, Rogers MJ. Protein geranylgeranylation is required for osteoclast formation, function, and survival: inhibition by bisphosphonates and GGTI-298. J Bone Miner Res 15: 1467–1476, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coxon FP, Rogers MJ. The role of prenylated small GTP-binding proteins in the regulation of osteoclast function. Calcif Tissue Int 72: 80–84, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cullinane DM The role of osteocytes in bone regulation: mineral homeostasis versus mechanoreception. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2: 242–244, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Currey JD, Butler G. The mechanical properties of bone tissue in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 57: 810–814, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daan S, Barnes BM, Strijkstra AM. Warming up for sleep? Ground squirrels sleep during arousals from hibernation. Neurosci Lett 128: 265–268, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.David V, Lafage-Proust MH, Laroche N, Christian A, Ruegsegger P, Vico L. Two-week longitudinal survey of bone architecture alteration in the hindlimb-unloaded rat model of bone loss: sex differences. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E440–E447, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Bruin ED, Herzog R, Rozendal RH, Michel D, Stussi E. Estimation of geometric properties of cortical bone in spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81: 150–156, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Bruin ED, Vanwanseele B, Dambacher MA, Dietz V, Stussi E. Long-term changes in the tibia and radius bone mineral density following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 43: 96–101, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delmas PD, Wilson DM, Mann KG, Riggs BL. Effect of renal function on plasma levels of bone Gla-protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 57: 1028–1030, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Divieti P, Inomata N, Chapin K, Singh R, Juppner H, Bringhurst FR. Receptors for the carboxyl-terminal region of pth(1-84) are highly expressed in osteocytic cells. Endocrinology 142: 916–925, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Divieti P, John MR, Juppner H, Bringhurst FR. Human PTH-(7-84) inhibits bone resorption in vitro via actions independent of the type 1 PTH/PTHrP receptor. Endocrinology 143: 171–176, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donahue SW, Galley SA, Vaughan MR, Patterson-Buckendahl P, Demers LM, Vance JL, McGee ME. Parathyroid hormone may maintain bone formation in hibernating black bears (Ursus americanus) to prevent disuse osteoporosis. J Exp Biol 209: 1630–1638, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donahue SW, Vaughan MR, Demers LM, Donahue HJ. Bone formation is not impaired by hibernation (disuse) in black bears Ursus americanus. J Exp Biol 206: 4233–4239, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donahue SW, Vaughan MR, Demers LM, Donahue HJ. Serum markers of bone metabolism show bone loss in hibernating bears. Clin Orthop: 295–301, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Doty SB, Nunez EA. Activation of osteoclasts and the repopulation of bone surfaces following hibernation in the bat, Myotis lucifugus. Anat Rec 213: 481–495, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ducher G, Tournaire N, Meddahi-Pelle A, Benhamou CL, Courteix D. Short-term and long-term site-specific effects of tennis playing on trabecular and cortical bone at the distal radius. J Bone Miner Metab 24: 484–490, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ducy P, Amling M, Takeda S, Priemel M, Schilling AF, Beil FT, Shen J, Vinson C, Rueger JM, Karsenty G. Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: a central control of bone mass. Cell 100: 197–207, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ducy P, Desbois C, Boyce B, Pinero G, Story B, Dunstan C, Smith E, Bonadio J, Goldstein S, Gundberg C, Bradley A, Karsenty G. Increased bone formation in osteocalcin-deficient mice. Nature 382: 448–452, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dufour C, Holy X, Marie PJ. Skeletal unloading induces osteoblast apoptosis and targets α5β1-PI3K-Bcl-2 signaling in rat bone. Exp Cell Res 313: 394–403, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ehara Y, Yamaguchi M. Histomorphological confirmation of bone loss in the femoral-metaphyseal tissues of rats with skeletal unloading. Res Exp Med (Berl) 196: 163–170, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elefteriou F, Ahn JD, Takeda S, Starbuck M, Yang X, Liu X, Kondo H, Richards WG, Bannon TW, Noda M, Clement K, Vaisse C, Karsenty G. Leptin regulation of bone resorption by the sympathetic nervous system and CART. Nature 434: 514–520, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Epperson LE, Martin SL. Quantitative assessment of ground squirrel mRNA levels in multiple stages of hibernation. Physiol Genomics 10: 93–102, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eriksen EF, Charles P, Melsen F, Mosekilde L, Risteli L, Risteli J. Serum markers of type I collagen formation and degradation in metabolic bone disease: correlation with bone histomorphometry. J Bone Miner Res 8: 127–132, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eser P, Frotzler A, Zehnder Y, Denoth J. Fracture threshold in the femur and tibia of people with spinal cord injury as determined by peripheral quantitative computed tomography. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 86: 498–504, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eser P, Frotzler A, Zehnder Y, Wick L, Knecht H, Denoth J, Schiessl H. Relationship between the duration of paralysis and bone structure: a pQCT study of spinal cord injured individuals. Bone 34: 869–880, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feinblatt J, Belanger LF, Rasmussen H. Effect of phosphate infusion on bone metabolism and parathyroid hormone action. Am J Physiol 218: 1624–1631, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferren LG, South FE, Jacobs HK. Calcium and magnesium levels in tissues and serum of hibernating and cold-acclimated hamsters. Cryobiology 8: 506–508, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Floyd T, Nelson RA, Wynne GF. Calcium and bone metabolic homeostasis in active and denning black bears (Ursus americanus). Clin Orthop 8: 301–309, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Folk GE Physiological observations of subarctic bears under winter den conditions. In: Mammalian Hibernation, edited by Fisher KC, Dawe AR, Lyman CP, Schonbaum E and South Jr. FE. New York: American Elsevier Publishing Company, 1967, p. 75–85.

- 57.Folk GE, Folk MA, Minor JJ. Physiological condition of three species of bears in winter dens. International Conference on Bear Research and Management, 1972, p. 107–124.