Abstract

αB-crystallin (αBC) is a small heat shock protein expressed at high levels in the myocardium where it protects from ischemia-reperfusion damage. Ischemia-reperfusion activates p38 MAP kinase, leading to the phosphorylation of αBC on serine 59 (P-αBC-S59), enhancing its ability to protect myocardial cells from damage. In the heart, ischemia-reperfusion also causes the translocation of αBC from the cytosol to other cellular locations, one of which was recently shown to be mitochondria. However, it is not known whether αBC translocates to mitochondria during ischemia-reperfusion, nor is it known whether αBC phosphorylation takes place before or after translocation. In the present study, analyses of mitochondrial fractions isolated from mouse hearts subjected to various times of ex vivo ischemia-reperfusion showed that αBC translocation to mitochondria was maximal after 20 min of ischemia and then declined steadily during reperfusion. Phosphorylation of mitochondrial αBC was maximal after 30 min of ischemia, suggesting that at least in part it occurred after αBC association with mitochondria. Consistent with this was the finding that translocation of activated p38 to mitochondria was maximal after only 10 min of ischemia. The overexpression of αBC-AAE, which mimics αBC phosphorylated on serine 59, has been shown to stabilize mitochondrial membrane potential and to inhibit apoptosis. In the present study, infection of neonatal rat cardiac myocytes with adenovirus-encoded αBC-AAE decreased peroxide-induced mitochondrial cytochrome c release. These results suggest that during ischemia αBC translocates to mitochondria, where it is phosphorylated and contributes to modulating mitochondrial damage upon reperfusion.

Keywords: cardiac myocyte, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase

ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) in the heart leads to the generation of mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can contribute to myocardial damage (40, 49). A number of signaling cascades are activated by ROS generated during I/R, including the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), which have been associated with both tissue damage and protection (2–4, 11, 15, 19, 27, 35, 45, 51). p38 MAPK activation leads to the phosphorylation of the small heat shock protein (sHSP) αB-crystallin (αBC), one of the 10-member sHSP family of molecular chaperones (48). αBC is expressed in several tissues, including the lung, eye, brain, and skeletal muscle; however, its expression in the heart is particularly noteworthy, since it comprises 3–5% of the total protein in the myocardium (6, 12, 48).

Several studies using genetically modified mice have shown that αBC can protect the heart against various stresses. For example, compared with wild-type mouse hearts, the hearts from transgenic mice that overexpress αBC in a cardiac-specific manner exhibited less tissue damage and preserved contractile function when subjected to ex vivo I/R (43). αBC transgenic mice were also shown to be protected from overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy (30). The only currently available αBC knockout mouse model also harbors a deletion in a sHSP related to αBC, heat shock binding protein 2 (8), due to the head-to-head orientation of these two genes and the fact that they share a promoter (46). Consistent with the results using mice that overexpress αBC were the findings that when subjected to ex vivo I/R, the hearts from αBC/HSPB2 double knockout (DKO) mice were more susceptible to injury than hearts from wild-type mice, suggesting that either or both of these sHSPs were involved in protection under these conditions (26, 37). Moreover, αBC/HSPB2 DKO mouse hearts exhibited exaggerated overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy (30), which is also consistent with a protective effect. However, there have also been studies (5) using the same αBC/HSPB2 DKO mouse model reporting that the absence of these sHSPs fosters less myocardial damage when examined in in vivo models of I/R and ischemic preconditioning.

The phosphorylation of αBC in response to I/R may affect its chaperone function. In response to I/R and other stresses, αBC is phosphorylated on serine 59 (24) in a p38-dependent manner (1, 21). Moreover, a molecular mimic of phospho-αBC-S59, αBC-AAE, was shown to enhance the ability of αBC to protect cells against several different stresses that imitate I/R; in contrast, αBC-AAA, which blocks αBC phosphorylation, increased I/R-mediated myocardial cell death (36). Consistent with these findings are other studies (13) that have suggested that αBC phosphorylation may augment its chaperone activity.

In terms of its subcellular localization αBC is very dynamic. Several studies (9, 16, 17, 50) have demonstrated that in the heart, stress induces a large proportion of the total cellular αBC to move from a diffuse cytosolic locale to sarcomeres, where it has been hypothesized to stabilize myofilament structure. More recent studies (34) in mouse hearts have shown that in addition to sarcomeres, during ex vivo I/R, αBC translocates to mitochondria, where it has been postulated to reduced I/R damage. Also, phospho-αBC-S59, which has been found to be associated with mouse heart mitochondria, was shown to increase upon ex vivo I/R; moreover, inhibiting p38 decreased mitochondrial phospho-αBC-S59 and increased I/R damage (25). Taken together, these results suggest that αBC is phosphorylated and moves to mitochondria during I/R; however, the sequence of these events and full scope of their functional consequences are not well understood. Accordingly, the present study was undertaken to examine whether αBC translocates to mitochondria during I/R, whether it is phosphorylated before and/or after translocation, and whether phospho-αBC-S59 has functional effects on mitochondria in cardiomyocytes that are consistent with its ability to decrease I/R damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Approximately 100, 10- to 14-wk-old C57/BL6 mice (Mus musculus) were used in this study. All procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines. The animal protocol used in this study was approved by the San Diego State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In vivo myocardial infarction and immunocytofluorescence.

In vivo myocardial infarction and immunocytofluorescence were carried out as previously described (18, 47) using TOM20 (Abcam no. ab56783) at 7 μg/ml and PS59 αB-crystallin (Stressgen no. SPA-227) at 10 μg/ml. All other antibodies were previously described (25).

Ex vivo I/R.

Global no-flow ex vivo I/R was performed on a Langendorff apparatus, as previously described (37). Briefly, mice were treated with 500 U/kg of heparin 10 min before administration of 150 mg/kg of pentobarbital, both via intaperitoneal injection. Animals were then killed, and hearts were quickly removed and placed in ice-cold modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer. The aortas were then cannulated, and the hearts were mounted on a Langendorff apparatus and perfused with oxygenated Krebs-Henseleit buffer at a constant pressure of 80 mmHg. The left atria were removed, and water-filled balloons connected to a pressure transducer were inserted into the left ventricle and inflated to record left ventricle developed pressure. Hearts were electrically paced at 8.7 to 9.2 Hz via an electrode placed on the right atrium. After a 30-min equilibration period, hearts were subjected to varying times of ischemia with or without subsequent reperfusion. Hearts were submerged in buffer at 37°C at all times. After the appropriate treatment times, hearts were quickly removed from the apparatus, the right atria and any remaining vessels and connective tissue were removed, and hearts were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Hearts were stored at −80°C until processed.

Preparation of subcellular fractions.

Frozen hearts were pulverized while in dry ice and then homogenized in 1 ml of isolation buffer (70 mM sucrose, 190 mM mannitol, 20 mM HEPES, 0.2 mM EDTA, 200 μM sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.5 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate, and 1 mM PMSF). After homogenization, 70 μl of the homogenate were added to 400 μl of RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.5, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 200 μM sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.5 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate, and 1 mM PMSF), and this whole homogenate fraction was saved for immunoblot analysis. The remainder of each homogenate was centrifuged at 600 g for 10 min to remove nuclei and myofibrils. The resulting supernatant, containing mitochondria and membrane fractions, was centrifuged at 5,000 g for 15 min, producing a pellet enriched in mitochondria and a supernatant. The pellet was washed twice with 1 ml of isolation buffer and then resuspended in 400 μl of RIPA buffer to produce the final mitochondrial fraction. The supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 min. The resulting supernatant was the final cytosolic fraction.

Trypsin protection assay.

Mitochondria (200 μg of mitochondrial protein) were resuspended in 200 μl of isolation buffer and treated with or without trypsin (1 mg/ml) for 1 h on ice. Mitochondria were then collected by centrifugation at 5,000 g for 15 min, washed twice with isolation buffer containing soybean trypsin inhibitor (1 mg/ml), and then resuspended in 100 μl of RIPA buffer, also containing soybean trypsin inhibitor (1 mg/ml). Mitochondria were then analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of αBC (Stressgen; SPA-223), phospho-αBC-S59 (Stressgen; SPA-227), TOM 20 (Santa Cruz; sc-11415), and cytochrome oxidase subunit IV.

Cytochrome c release assay.

Neonatal rat ventricular myocyte cultures (NRVMC), prepared as previously described, were infected with recombinant adenovirus encoding either no αBC (AdV-control), wild-type αBC (AdV-αBC), or a mutant form of αBC that mimics phosphorylation at serine 59, while blocking phosphorylation at serines 19 and 45 (αBC-AAE). Forty-eight hours after infection, cultures were subjected to 200 μM H2O2 for 1 h, after which cells were harvested by trypsinization, collected by centrifugation, and subjected to subcellular fractionation by differential centrifugation to yield a pure cytosolic fraction. Western blotting, using anti-cytochrome c antibody (BD Pharmingen; 556433), was performed to analyze cytochrome c release into the cytosol.

RESULTS

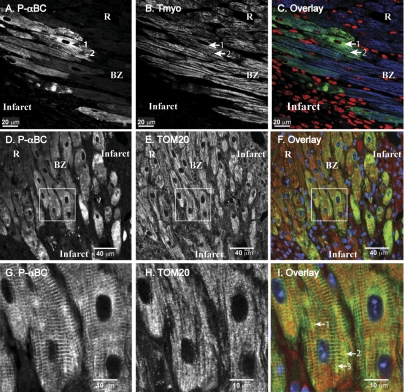

To determine whether phospho-αBC-S59 is generated in stressed cardiac myocytes in vivo, confocal immunocytofluorescence microscopy was used to examine sections of hearts from a previously described in vivo mouse model of permanent occlusion myocardial infarction (18, 47). Sections prepared from mice euthanized 4 days after infarction were stained with an antibody specific for phospho-αBC-S59. A subset of tropomyosin-positive myocytes in the infarct border zone stained positively for phospho-αBC-S59 (Fig. 1, A and B, BZ), while tropomyosin-positive myocytes in a region remote from the infarct did not stain for phospho-αBC-S59 (Fig. 1 A and B, R). A significant amount of the phospho-αBC-S59 and tropomyosin colocalized (Fig. 1, A-C, arrow 1), consistent with the sarcomeric association of phospho-αBC-S59. However, a portion of the phospho-αBC-S59 did not colocalize with tropomyosin (e.g., Fig. 1, A and C, arrow 2), consistent with the localization of phospho-αBC-S59 to other structures, such as mitochondria. To further examine this possibility, heart sections were stained for phospho-αBC-S59 and the mitochondrial outer membrane protein TOM20. As expected, phospho-αBC-S59 staining was increased in the infarct border zone (Fig. 1D), while TOM20 staining was more uniform throughout the section (Fig. 1E). Examination of a portion of this image (e.g., Fig. 1F, box) at a higher power showed that while most of the phospho-αBC-S59 assumed a sarcomeric pattern, as expected (Fig. 1G), there were numerous areas where phospho-αBC-S59 and TOM20 colocalized (Fig. 1I, arrows 1, 2, and 3). These results are consistent with the generation of phospho-αBC-S59 in ischemic cardiac myocytes in vivo and its localization to sarcomeres and mitochondria.

Fig. 1.

Confocal immunocytofluorescence analysis of phospho-αB-crystallin (αBC)-S59 in mouse hearts after myocardial infarction. FVB mice were subjected to in vivo myocardial infarction via permanent occlusion of the left ascending coronary artery. Four days after the surgery, mice were euthanized and sections were prepared. All procedures have been previously described (18, 47). Micrograph represents results from 3 different mice. A: section of a mouse heart that included the infarct and surviving myocytes in the border zone (BZ) and in a remote region, distant from the infarct (R), was stained for phospho-αBC-S59 (P-αBC). Arrow 1 points to nonsarcomeric phospho-αBC-S59, while arrow 2 points to phospho-αBC-S59 that stained in a sarcomeric pattern. B: section sequential to that shown in A was stained for tropomyosin. Arrows 1 and 2 point to the same regions of the same cells as in A. C: sections shown in A and B were overlayered and the P-αBC, tropomyosin, and nuclei stainings are shown in green, blue, and red, respectively. Arrows 1 and 2 point to same regions of same cells as in A and B. D and G: section of a mouse heart that included the infarct and surviving myocytes in the border zone and in a remote region, distant from the infarct, was stained for phospho-αBC-S59. Box shows region that was scanned at a higher magnification in G. E and H: section sequential to that shown in D was stained for TOM20. Box shows region that was scanned at a higher magnification in H. F and I: sections shown in D and G were overlayered and the P-αBC, tropomyosin, and nuclei stainings are shown in green, red, and blue, respectively. Arrows 1, 2, and 3 point to same regions of same cells as in D and G.

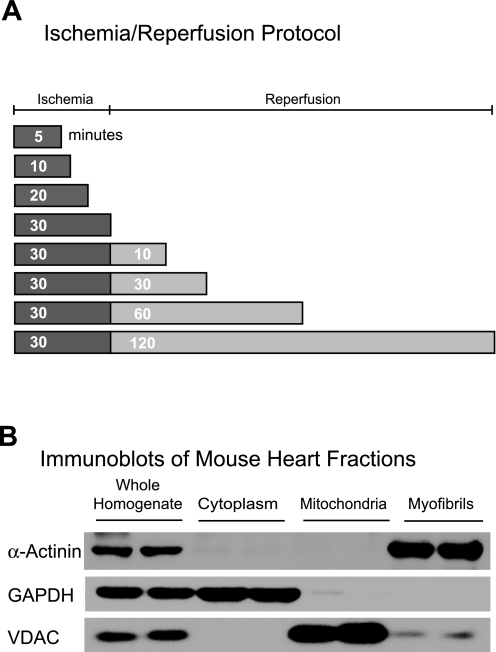

To examine the molecular details of phospho-αBC-S59 generation and localization to mitochondria in the heart and to determine whether phospho-αBC-S59 is generated during I/R, mouse hearts were subjected to ex vivo ischemia or I/R for various times (Fig. 2A) and then homogenized and subjected subcellular fractionation. Immunoblotting for the myofibril, cytosol, and mitochondria marker proteins, α-actinin, GAPDH, and voltage-dependent anion channel, respectively, in subcellular fractions prepared from a control heart showed that the mitochondrial fractions were relatively pure and did not contain significant amounts of proteins from the cytosol and myofibril fractions (Fig. 2B), which can potentially contain large quantities of αBC.

Fig. 2.

Diagram of the ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) protocol used in this study and subcellular fractionation. A: after 30 min of equilibration mouse hearts were subjected to various times of I/R on a Langendorff apparatus (n = 3 mouse hearts/time). A continual perfusion control that matched each ischemia and I/R time was also generated. B: after each treatment, hearts were homogenized and, after removal of a sample for later analysis, homogenates were subjected to subcellular fractionation. Tissue was later homogenized and fractionated by differential centrifugation and examined by immunoblot for α-actinin, GAPDH, and voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), which are marker proteins for myofibrils, cytosol, and mitochondria, respectively.

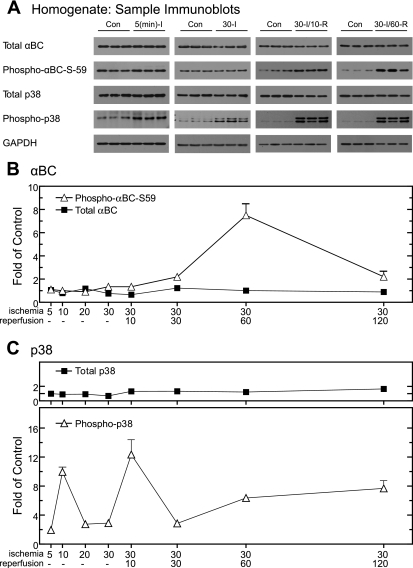

Whole homogenates prepared from hearts subjected to the I/R protocols shown in Fig. 2A were examined by immunoblotting; sample blots are shown in Fig. 3A. An antibody that cross-reacts with all forms of αBC, regardless of phosphorylation state, was used to measure total αBC in homogenates. Compared with control hearts, the levels of total αBC in hearts subjected to ischemia or I/R did not change significantly (Fig. 3A, total αBC). Quantification of immunoblots performed using samples obtained after at all ischemia and I/R times examined further demonstrated that compared with perfusion time-matched controls, there was no significant change in the level of total αBC (Fig. 3B, total αBC). In contrast, phospho-αBC-S59 in whole heart homogenates reached a maximum of eightfold over control after 30 min of ischemia/60 min of reperfusion (Fig. 3A, phospho-αBC-S59; Fig. 3B). Since the phosphorylation of αBC on serine 59 depends on p38 activation, the levels of total and phosphorylated (i.e., active) p38 were also examined. As expected, total p38 did not change as a function of I/R (Fig. 3A, total p38; Fig. 3C, total p38). However, the relative levels of phospho-p38 increased transiently to ∼10-fold over control within 10 min of ischemia and then decreased to about threefold over control at the longer ischemia times (Fig. 3A, phospho-p38; Fig. 3C, phospho-p38). Phospho-p38 exhibited a s transient increase of 12-fold over control after 30 min of ischemia/10 min reperfusion, which was followed by more modest increases to approximately six- to eightfold over control after 60 and 120 min of reperfusion, respectively. This profile of p38 activation is consistent with the previously observed transient activation of p38 during ischemia (44) and reactivation again during reperfusion (39), the latter of which requires mitochondrial-derived ROS (14). These results demonstrate that αBC serine 59 phosphorylation occurred primarily during reperfusion when whole heart homogenates were examined.

Fig. 3.

Effect of ischemia or I/R on αBC, phospho-αBC-S59, p38, and phospho-p38 in whole heart homogenates. Before subcellular fractionation, samples of the whole heart homogenates from the 8 experimental samples shown in Fig. 1A, and 8 time-matched controls (n = 3 hearts per time), were subjected to immunoblot analysis. A: samples from 4 of the time points were analyzed by immunoblotting for total αBC, phospho-αBC-S59, p38, phospho-p38, and GAPDH. B: immunoblots of all samples for total αBC (▪) and phospho-αBC-S59 (▵) were quantified; values are shown as fold over control hearts for each time point normalized to GAPDH. C: immunoblots of all samples for total p38 (▪) and phospho-p38 (▵) were quantified; values are shown as fold over control hearts for each time point normalized to GAPDH. All values are means ± SE; n = 3 for each time point. All values for phospho-αBC-S59 and phospho-p38 are significantly greater than control perfusion values (P < 0.05). In cases where error bars are not visible, they are smaller than the symbol. The reason for observing the doublet in some phospho-p38 lanes is not known, but it could be the result of proteases that are activated during ischemia and I/R, such as calpain, that can cleave p38.

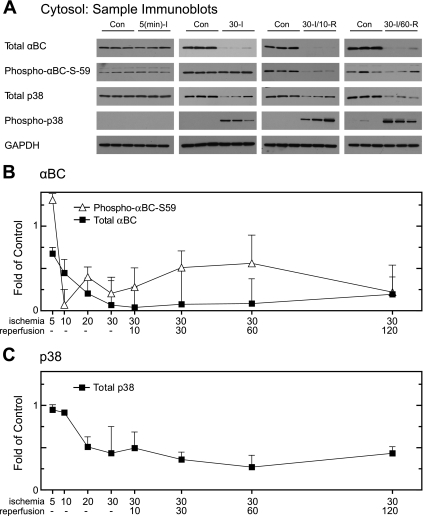

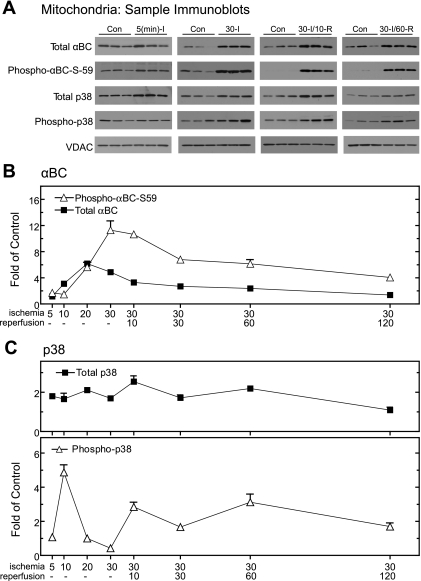

Although the levels of αBC in whole heart homogenates did not change upon I/R, after as little as 5 min of ischemia there was a decrease in total αBC and phospho-αBC-S59 from the cytosol, which progressed until there was essentially no αBC in the cytosol after 30 min of ischemia (Fig. 4A). This pattern persisted throughout all reperfusion times examined (e.g., Fig. 4B, total αBC). Interestingly, while total p38 in the cytosol also decreased precipitously after as little as 20 min of ischemia, a large proportion of the p38 that remained in the cytosol after the onset of ischemia was phosphorylated, suggesting a high degree of activation (Fig. 4, B and C). Accordingly, it was apparent that during ischemia αBC and p38 quantitatively relocated from the cytosol to other subcellular fractions.1 To examine possible localization of αBC and p38 to mitochondria, immunoblots were prepared from mitochondrial fractions of hearts subjected to various I/R times. Total αBC in mitochondrial fractions increased primarily during ischemia (Fig. 5A, total αBC) on a time frame that coordinated with the loss of αBC from the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 4). Quantification of blots of all ischemia and I/R times demonstrated that total mitochondrial αBC increased by about fourfold after as little as 10 min of ischemia, reaching a maximum of sixfold over control after 20 min of ischemia, followed by a decline through the remaining times examined (Fig. 5B, total αBC).

Fig. 4.

Effect of ischemia and I/R on αBC in cytosolic fractions. Immunoblotting was performed on cytosolic fractions from all the time points to examine total αBC and GAPDH. After subcellular fractionation, samples of the cytosolic fractions from the 8 experimental samples shown in Fig. 1A, and 8 time-matched controls (n = 3 hearts per time), were subjected to immunoblot analysis. A: samples from 4 of the time points were analyzed by immunoblotting for total αBC, phospho-αBC-S59, p38, phospho-p38, and GAPDH, as labeled. B: immunoblots of all samples for total αBC (▪) and phospho-αBC-S59 (▵) were quantified; values are shown as fold over control hearts for each time point normalized to VDAC. C: immunoblots of all samples for total p38 (▪) were quantified; values are shown as fold over control hearts for each time point normalized to VDAC. All values are means ± SE; n = 3 for each time point. All values are significantly greater than control perfusion values (P < 0.05). In cases where error bars are not visible, they are smaller than the symbol. Due to the lack of signal in control lanes, it was not possible to determine the proportion of total p38 that was phosphorylated under control conditions, so only total p38 is shown in this figure.

Fig. 5.

Effect of ischemia and I/R on αBC, phospho-αBC-S59, p38, and phospho-p38 in mitochondrial fractions. After subcellular fractionation, samples of the mitochondrial fractions from the 8 experimental samples shown in Fig. 1A, and 8 time-matched controls (n = 3 hearts per time), were subjected to immunoblot analysis. A: samples from 4 of the time points were analyzed by immunoblotting for total αBC, phospho-αBC-S59, p38, phospho-p38, and VDAC, as labeled. B: immunoblots of all samples for total αBC (▪) and phospho-αBC-S59 (▵) were quantified; values are shown as fold over control hearts for each time point normalized to VDAC. C: immunoblots of all samples for total p38 (▪) and phospho-p38 (▵) were quantified; values are shown as fold over control hearts for each time point normalized to VDAC. All values are means ± SE; n = 3 for each time point. All values are significantly greater than control perfusion values (P < 0.05). In cases where error bars are not visible, they are smaller than the symbol.

The level of mitochondrial phospho-αBC-S59 was also maximal during I, but exhibited delayed kinetics compared with that of total mitochondrial αBC (Fig. 5, A and B, phospho-αBC-S59). In fact, mitochondrial phospho-αBC-S59 was maximal after 30 min of ischemia, 10 min after the maximum for total αBC. At longer reperfusion times, the level of mitochondrial phoshpo-αBC-S59 declined steadily to about fourfold over control after 120 min of reperfusion, the last time point examined (Fig. 5B, phospho-αBC-S59).2

Since it appeared as though αBC phosphorylation occurred after translocation to mitochondria, and since p38 activation is required for this phosphorylation, the levels of p38 in the mitochondrial fractions were analyzed. Total p38 in mitochondrial fractions increased by about twofold over control within 5 min of the onset of ischemia (Fig. 5, A and C, total p38). Total mitochondrial p38 remained at this level through 60 min of reperfusion, and then declined somewhat thereafter. The levels of phospho-p38 in the mitochondrial fractions exhibited a transient increase to about fivefold over control within 10 min of ischemia, which was followed by a decline to nearly control levels of phosphorylation at the later ischemia times (Fig. 5, A and B, phospho-p38). Mitochondrial phsopho-p38 increased to ∼2.5-fold over control upon 10 min of reperfusion, remained at this level through 60 min of reperfusion, and then declined to control levels by 120 min or reperfusion. Taken together, these results indicate that in contrast to what was observed in whole heart homogenates, the increases in mitochondrial total αBC and phospho-αBC-S59 occurred primarily during ischemia. Moreover, the timing of the increases in phospho-p38 in mitochondrial fractions provided support for the idea that αBC is phosphorylated in a p38-dependent manner and that at least in part this phosphorylation takes place after its translocation to mitochondria.

To examine the nature of the association of αBC with mitochondria, a protease protection analysis was carried out. After treatment of isolated mitochondria with trypsin, total αBC and phospho-αBC-S59 were both decreased by ∼50% (Fig. 6, A and C), indicating that about one-half of the αBC is located on the mitochondrial surface, while the remainder may be localized to regions of mitochondria that are protected from trypsin. To examine the effects of trypsin on other proteins of known mitochondrial localization, immunoblots were carried out for TOM20, which resides on the mitochondrial surface, and for cyclooxygenase (COX)-4, which is in the matrix. As expected, TOM 20 was completely digested by trypsin, while COX-4 was completely resistant to protease treatment (Fig. 6A, TOM20 and COX IV). To address the formal possibility that some forms of αBC are less susceptible to degradation by trypsin, mitochondria were subjected to sonication before protease treatment, and it was found that both αBC and COX-4 were completely degraded. Taken together, these results suggest that approximately one-half of the mitochondrial αBC and phospho-αBC-S59 reside on the outer mitochondrial membrane surface, while the remainder may be localized within the outer mitochondrial membrane.

Fig. 6.

Effect of trypsin on mitochondrial αBC. Hearts (n = 3) were subjected to 30 min of ex vivo ischemia followed by 10 min of reperfusion then homogenized and mitochondria isolated, as described in materials and methods; 200 μg of isolated mitochondrial protein were then treated with 1 mg/ml trypsin for 1 h at 4°C. A: immunoblots for total αBC, phospho-αBC-S59, TOM20, and cyclooxygenase (COX)-4 before (Con) and after (Trypsin) incubating isolated mitochondria with trypsin. TOM20 was used as a marker for proteins located outside the mitochondrial outer membrane and COX-4 was used as a marker for proteins located within the outer mitochondrial membrane. B: immunoblots for total αBC, phospho-αBC-S59, TOM20, and COX-4 after mitochondrial membrane disruption by sonication. C: quantitation of the fraction of total αBC, phospho-αBC-S59, COX-4, and TOM20 remaining after trypsin treatment of intact mitochondria. Values are represented as mean percent remaining ± SE; n = 3.

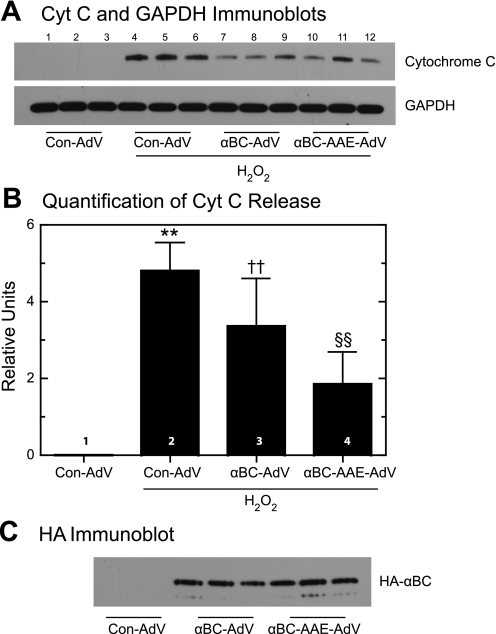

To examine functional roles for mitochondrial αBC, the effects of overexpressing wild-type αBC, or αBC-AAE, the latter of which mimics phosphorylation at serine 59, in cultured cardiac myocytes were assessed (36). When cultures were infected with the control adenovirus Con-AdV but not subjected to oxidative stress, there was no detectible release of mitochondrial cytochrome c, as expected (Fig. 7A, lanes 1–3; Fig. 6B, bar 1). However, when Con-AdV-infected cultures were treated with H2O2, the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c increased dramatically (Fig. 7A, lanes 4–6; Fig. 7B, bar 2). In contrast, when cultures were infected with αBC-AdV or αBC-AAE-AdV, which encode similar amounts of each transgene in NRVMC (25), H2O2-activated cytochrome c release decreased by ∼25 and 50%, respectively (Fig. 7A, lanes 7–12; Fig. 7B, bars 3 and 4), suggesting that αBC protects mitochondria from oxidative damage and that phosphorylation of αBC on serine 59 may enhance this protective effect. Consistent with the abilities of these forms of αBC to effect changes in mitochondrial function was the finding that both HA-αBC and HA-αBC-AAE were associated with mitochondria isolated from AdV-infected NRVMC (Fig. 7C). This suggests that HA-αBC might become phosphorylated upon arrival at mitochondria or that either native or phosphorylated αBC can associate with mitochondria. Alternatively, it is possible that αBC-AAE in the cytosol and on sarcomeres could indirectly account for the reduced cytochrome c release. Taken together, the results shown in Fig. 7 are consistent with our previous findings that αBC-AdV and αBC-AAE-AdV reduce H2O2-mediated loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in NRVMC and that αBC-AAE is more effective in this regard than wild-type αBC (25).

Fig. 7.

Effect of wild-type αBC-AdV and αBC-AAE-AdV on H2O2-induced cytochrome c release. Overexpression of wild-type αBC or the phosphorylation mimic αBC-AAE in neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes was accomplished via infection with adenovirus (AdV) harboring the appropriate expression construct, or no αBC expression construct (Con-AdV). Cells were treated with 200 μM H2O2 for 1 h, followed by subcellular fractionation and cytochrome c immunoblotting on the cytosolic fraction. A: immunoblots of cytochrome c and GAPDH in the cytosol. B: immunoblot shown in A was quantified to determine the levels of cytosolic cytochrome c relative to GAPDH. Values represent average ± SE; n = 3. **P < 0.05, ††P < 0.05, and §§P < 0.05, different from each other and the control, as determined by ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test. C: immunoblot for HA-tagged, AdV-encoded wild-type αBC, or αBC-AAE in mitochondrial fractions isolated from cultured cardiac myocytes.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to show that in an ex vivo mouse heart model of I/R ischemia induces a nearly complete disappearance of αBC from the cytosol that coordinates temporally with the appearance of αBC in mitochondrial fractions. Moreover, the results of these studies are consistent with the hypothesis that the ischemia-mediated translocation of p38 and αBC to mitochondria, and the p38-dependent phosphorylation of αBC, occur in a sequence suggesting that αBC phosphorylation can take place at the mitochondrion. These findings raise questions about the mechanisms responsible for αBC translocation to, and phosphorylation at mitochondria, as well as precisely where in and/or on mitochondria αBC is located, and what the functional roles of αBC are in terms of mitochondrial function during ischemic stress.

The mechanism responsible for αBC translocation to mitochondria is not known; however, previous studies on cardiac myocytes and other cell types suggest that the chaperone activity of αBC is likely to play a central role. For example, αBC binds to numerous sarcomeric proteins (6, 9, 10), where it is believed to help maintain contractile element integrity during stress (17). Additionally, in C2C12 myoblasts and in cultured carcinoma cells, αBC binds to procaspase 3 and inhibits its autocatalytic activation (22, 28, 29). In rabbit N/N1003A lens epithelial cells, αBC interacts with p53 and decreases its translocation to mitochondria, thus modulating p53-mediated apoptosis in this cell type (31). αBC also binds to the proapoptotic BH3-only proteins Bax and Bcl-xs in the cytosol of human lens epithelial cells and in so doing impedes their translocation to mitochondria, thereby inhibiting apoptosis (33). While none of these reports describe αBC association with mitochondria, it is possible that a portion of the cytosolic proteins to which αBC binds also translocate to mitochondria. In this way, αBC translocation would occur by virtue of a binding partner and not due to direct interaction of αBC with mitochondrial proteins. An additional stimulus for αBC translocation to mitochondria is the unfolding of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins. For example, the mitochondrial outer membrane protein TOM20, which is part of the mitochondrial protein import system, is prone to unfolding during myocardial ischemia, and other chaperones, including HSP79 and HSP90, are known to bind to it, as well as other TOM subunits under these conditions (7). Additionally, it has been postulated that mitochondrial permeability transition pore proteins unfold during oxidative stress and that modulating this unfolding through the binding of chaperones may decrease permeability transition and the associated apoptotic cell death (20). Accordingly, acting as a chaperone, αBC might bind to proteins in the cytosol that translocate to mitochondria, or it may bind to proteins on the outer mitochondrial membrane that unfold during ischemia. Perhaps it is through these interactions that αBC contributes to the retention of proper mitochondrial function during this extreme stress.

In the present study, the kinetics of ischemia-mediated αBC translocation and phosphorylation were consistent with the possibility that at least a portion of αBC phosphorylation occurred in the mitochondrial fraction. The known dependence of αBC phosphorylation on the p38-activated MAPK-activated protein kinase-2 (21, 23, 24) is consistent with the findings in the current study that increased levels of activated p38 were associated with mitochondrial fractions after ischemia (Fig. 5C). Previous studies (42) showing that αBC can form a complex with p38, which itself can translocate to mitochondria during stress, provide further support for the possibility that αBC may associate with mitochondria by binding to other proteins that translocate from the cytosol to mitochondria. These findings complement other recent studies (38, 41, 52) in cardiac myocytes and other cell types documenting the translocation of numerous signaling kinases, including PKC, PKA, ERK, JNK, Akt, hexokinase, and GSK3β, from the cytosol to mitochondria. It is apparent that most of these kinases translocate to the surface of mitochondria and, in some cases, gain entry to the interior of mitochondria and that their functions are exerted by phosphorylated key proteins located on or in mitochondria.

An examination of whether αBC is on or in mitochondria was also examined in the present study. It was shown that at least one-half of the phospho-αBC-S59 was susceptible to proteolytic degradation, suggesting that αBC localizes on the surface of mitochondria during ischemia but that the remaining, protease-resistant portion might be within the outer membrane (Fig. 6). Since αBC does not have a canonical mitochondrial targeting sequence, the mechanism by which it might gain entry to the interior of the mitochondrion is unclear. It is known that the posttranslational translocation of mitochondrial proteins through the TOM/TIM translocation machinery requires the partial unfolding of proteins on the exterior of mitochondria and the subsequent refolding during and/or after translocation across the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes, which is known to require other heat shock proteins, such as HSP70 and HSP90. Thus it is possible that αBC participates in this process and helps to ensure proper translocation and refolding of proteins residing within mitochondria.

In the present study, the potential functional consequence of the association of αBC with mitochondria was examined in cultured cardiac myocytes, where it was shown that αBC-AAE, which mimics phospho-αBC-S59, decreased the oxidative-stress-dependent release of cytochrome c (Fig. 7, A and B). This finding is consistent with our previous observation that αBC-AAE confers a retention of mitochondrial membrane potential, attenuates calcium-induced mitochondrial swelling in vitro (25), and reduces mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in cardiac myocytes (36). This finding is also consistent with a report (32) showing that overexpression of αBC in human umbilical vein endothelial cells decreased ROS generation and apoptosis in this cell type (32).

A great deal remains to be discovered about how αBC interacts with mitochondria during ischemia, as well as how such an interaction enhances mitochondrial recovery during reperfusion. In addition to the results of the present study, several other recent studies (5, 26) have implicated a role for αBC in modulating mitochondrial function in the heart. Thus it is quite probable that one of the manifold ways in which αBC fosters cardioprotection is through the physical interaction with mitochondria and the specific binding to key mitochondrial proteins in ways that augment the ability of mitochondria to preserve proper metabolic function and withstand the rigors of I/R stress.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-085577. R. Whittaker is a Fellow of the Rees-Stealy Research Foundation and the San Diego State University Heart Institute.

Acknowledgments

We thank Donna Thuerauf for expert technical assistance and review of the manuscript; Peter Belmont, Shirin Doroudgar, Archana Tadimalla, and John Vekich for helpful discussions; and Nicole Gellings-Lowe for critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The levels of phospho-p38 were too low to detect in cytosolic samples; accordingly, quantification of the percentage of total p38 that was phosphorylated was not possible. Therefore, Fig. 4C shows only total p38.

Since there was an increase in phospho-αBC-S59 during I in mitochondrial samples (Fig. 5B) that was not observed in whole homogenate samples (Fig. 3B), it is probable that mitochondrial phospho-αBC-S59 constitutes a relatively small proportion of the total phospho-αBC-S59 in cardiac myocytes under these conditions. This is consistent with previous findings that other subcellular fractions, e.g., myofilaments, serve as a major sink for αBC translocation in I/R stressed cardiac myocytes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggeli IK, Beis I, Gaitanaki C. Oxidative stress and calpain inhibition induce alpha B-crystallin phosphorylation via p38-MAPK and calcium signaling pathways in H9c2 cells. Cell Signal 20: 1292–1302, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baines CP, Molkentin JD. STRESS signaling pathways that modulate cardiac myocyte apoptosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 38: 47–62, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barancik M, Htun P, Strohm C, Kilian S, Schaper W. Inhibition of the cardiac p38-MAPK pathway by SB203580 delays ischemic cell death. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 35: 474–483, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassi R, Heads R, Marber MS, Clark JE. Targeting p38-MAPK in the ischaemic heart: kill or cure? Curr Opin Pharmacol 8: 141–146, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin IJ, Guo Y, Srinivasan S, Boudina S, Taylor RP, Rajasekaran NS, Gottlieb R, Wawrousek EF, Abel ED, Bolli R. CRYAB and HSPB2 deficiency alters cardiac metabolism and paradoxically confers protection against myocardial ischemia in aging mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H3201–H3209, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennardini F, Wrzosek A, Chiesi M. Alpha B-crystallin in cardiac tissue. Association with actin and desmin filaments. Circ Res 71: 288–294, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowers M, Ardehali H. TOM20 and the heartbreakers: evidence for the role of mitochondrial transport proteins in cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol 41: 406–409, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brady JP, Garland DL, Green DE, Tamm ER, Giblin FJ, Wawrousek EF. AlphaB-crystallin in lens development and muscle integrity: a gene knockout approach. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42: 2924–2934, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullard B, Ferguson C, Minajeva A, Leake MC, Gautel M, Labeit D, Ding L, Labeit S, Horwitz J, Leonard KR, Linke WA. Association of the chaperone alphaB-crystallin with titin in heart muscle. J Biol Chem 279: 7917–7924, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiesi M, Longoni S, Limbruno U. Cardiac alpha-crystallin. III. Involvement during heart ischemia. Mol Cell Biochem 97: 129–136, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig R, Larkin A, Mingo AM, Thuerauf DJ, Andrews C, McDonough PM, Glembotski CC. p38 MAPK and NF-kappa B collaborate to induce interleukin-6 gene expression and release. Evidence for a cytoprotective autocrine signaling pathway in a cardiac myocyte model system. J Biol Chem 275: 23814–23824, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubin RA, Wawrousek EF, Piatigorsky J. Expression of the murine alpha B-crystallin gene is not restricted to the lens. Mol Cell Biol 9: 1083–1091, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ecroyd H, Meehan S, Horwitz J, Aquilina JA, Benesch JL, Robinson CV, Macphee CE, Carver JA. Mimicking phosphorylation of alphaB-crystallin affects its chaperone activity. Biochem J 401: 129–141, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emerling BM, Platanias LC, Black E, Nebreda AR, Davis RJ, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for hypoxia signaling. Mol Cell Biol 25: 4853–4862, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer P, Hilfiker-Kleiner D. Role of gp130-mediated signalling pathways in the heart and its impact on potential therapeutic aspects. Br J Pharmacol 153, Suppl 1: S414–S427, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golenhofen N, Htun P, Ness W, Koob R, Schaper W, Drenckhahn D. Binding of the stress protein alpha B-crystallin to cardiac myofibrils correlates with the degree of myocardial damage during ischemia/reperfusion in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol 31: 569–580, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golenhofen N, Ness W, Koob R, Htun P, Schaper W, Drenckhahn D. Ischemia-induced phosphorylation and translocation of stress protein alpha B-crystallin to Z lines of myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 274: H1457–H1464, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gude NA, Emmanuel G, Wu W, Cottage CT, Fischer K, Quijada P, Muraski JA, Alvarez R, Rubio M, Schaefer E, Sussman MA. Activation of Notch-mediated protective signaling in the myocardium. Circ Res 102: 1025–1035, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hausenloy DJ, Tsang A, Mocanu MM, Yellon DM. Ischemic preconditioning protects by activating prosurvival kinases at reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H971–H976, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He L, Lemasters JJ. Regulated and unregulated mitochondrial permeability transition pores: a new paradigm of pore structure and function? FEBS Lett 512: 1–7, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoover HE, Thuerauf DJ, Martindale JJ, Glembotski CC. alpha B-crystallin gene induction and phosphorylation by MKK6-activated p38. A potential role for alpha B-crystallin as a target of the p38 branch of the cardiac stress response. J Biol Chem 275: 23825–23833, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda R, Yoshida K, Ushiyama M, Yamaguchi T, Iwashita K, Futagawa T, Shibayama Y, Oiso S, Takeda Y, Kariyazono H, Furukawa T, Nakamura K, Akiyama S, Inoue I, Yamada K. The small heat shock protein alphaB-crystallin inhibits differentiation-induced caspase 3 activation and myogenic differentiation. Biol Pharm Bull 29: 1815–1819, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito H, Kamei K, Iwamoto I, Inaguma Y, Garcia-Mata R, Sztul E, Kato K. Inhibition of proteasomes induces accumulation, phosphorylation, and recruitment of HSP27 and alphaB-crystallin to aggresomes. J Biochem 131: 593–603, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito H, Okamoto K, Nakayama H, Isobe T, Kato K. Phosphorylation of alphaB-crystallin in response to various types of stress. J Biol Chem 272: 29934–29941, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin JK, Whittaker R, Glassy MS, Barlow SB, Gottlieb RA, Glembotski CC. Localization of phosphorylated αB-crystallin to heart mitochondria during ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H337–H344, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadono T, Zhang XQ, Srinivasan S, Ishida H, Barry WH, Benjamin IJ. CRYAB and HSPB2 deficiency increases myocyte mitochondrial permeability transition and mitochondrial calcium uptake. J Mol Cell Cardiol 40: 783–789, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaiser RA, Bueno OF, Lips DJ, Doevendans PA, Jones F, Kimball TF, Molkentin JD. Targeted inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase antagonizes cardiac injury and cell death following ischemia-reperfusion in vivo. J Biol Chem 279: 15524–15530, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamradt MC, Chen F, Cryns VL. The small heat shock protein alpha B-crystallin negatively regulates cytochrome c- and caspase-8-dependent activation of caspase-3 by inhibiting its autoproteolytic maturation. J Biol Chem 276: 16059–16063, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamradt MC, Chen F, Sam S, Cryns VL. The small heat shock protein alpha B-crystallin negatively regulates apoptosis during myogenic differentiation by inhibiting caspase-3 activation. J Biol Chem 277: 38731–38736, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumarapeli AR, Su H, Huang W, Tang M, Zheng H, Horak KM, Li M, Wang X. αB-crystallin suppresses pressure overload cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res 103: 1473–1482. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li DW, Liu JP, Mao YW, Xiang H, Wang J, Ma WY, Dong Z, Pike HM, Brown RE, Reed JC. Calcium-activated RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway mediates p53-dependent apoptosis and is abrogated by alpha B-crystallin through inhibition of RAS activation. Mol Biol Cell 16: 4437–4453, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu B, Bhat M, Nagaraj RH. AlphaB-crystallin inhibits glucose-induced apoptosis in vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 321: 254–258, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mao YW, Liu JP, Xiang H, Li DW. Human alphaA- and alphaB-crystallins bind to Bax and Bcl-X(S) to sequester their translocation during staurosporine-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 11: 512–526, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martindale JJ, Wall JA, Martinez-Longoria DM, Aryal P, Rockman HA, Guo Y, Bolli R, Glembotski CC. Overexpression of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6 in the heart improves functional recovery from ischemia in vitro and protects against myocardial infarction in vivo. J Biol Chem 280: 669–676, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moolman JA, Hartley S, Van Wyk J, Marais E, Lochner A. Inhibition of myocardial apoptosis by ischaemic and beta-adrenergic preconditioning is dependent on p38 MAPK. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 20: 13–25, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrison LE, Hoover HE, Thuerauf DJ, Glembotski CC. Mimicking phosphorylation of alphaB-crystallin on serine-59 is necessary and sufficient to provide maximal protection of cardiac myocytes from apoptosis. Circ Res 92: 203–211, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrison LE, Whittaker RJ, Klepper RE, Wawrousek EF, Glembotski CC. Roles for alphaB-crystallin and HSPB2 in protecting the myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion-induced damage in a KO mouse model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H847–H855, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohori K, Miura T, Tanno M, Miki T, Sato T, Ishikawa S, Horio Y, Shimamoto K. Ser9 phosphorylation of mitochondrial GSK-3β is a primary mechanism of cardiomyocyte protection by erythropoietin against oxidant-induced apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H2079–H2086, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okada T, Otani H, Wu Y, Kyoi S, Enoki C, Fujiwara H, Sumida T, Hattori R, Imamura H. Role of F-actin organization in p38 MAP kinase-mediated apoptosis and necrosis in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes subjected to simulated ischemia and reoxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H2310–H2318, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piper HM, Abdallah Y, Schafer C. The first minutes of reperfusion: a window of opportunity for cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res 61: 365–371, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poderoso C, Converso DP, Maloberti P, Duarte A, Neuman I, Galli S, Maciel FC, Paz C, Carreras MC, Poderoso JJ, Podesta EJ. A mitochondrial kinase complex is essential to mediate an ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation of a key regulatory protein in steroid biosynthesis. PLoS ONE 3: e1443, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Rane MJ, Coxon PY, Powell DW, Webster R, Klein JB, Pierce W, Ping P, McLeish KR. p38 Kinase-dependent MAPKAPK-2 activation functions as 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-2 for Akt in human neutrophils. J Biol Chem 276: 3517–3523, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ray PS, Martin JL, Swanson EA, Otani H, Dillmann WH, Das DK. Transgene overexpression of alphaB crystallin confers simultaneous protection against cardiomyocyte apoptosis and necrosis during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. FASEB J 15: 393–402, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steenbergen C The role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury; relationship to ischemic preconditioning. Basic Res Cardiol 97: 276–285, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sugden PH, Clerk A. Oxidative stress and growth-regulating intracellular signaling pathways in cardiac myocytes. Antioxid Redox Signal 8: 2111–2124, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swamynathan SK, Piatigorsky J. Orientation-dependent influence of an intergenic enhancer on the promoter activity of the divergently transcribed mouse Shsp/alpha B-crystallin and Mkbp/HspB2 genes. J Biol Chem 277: 49700–49706, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tadimalla A, Belmont PJ, Thuerauf DJ, Glassy MS, Martindale JJ, Gude N, Sussman MA, Glembotski CC. Mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor is an ischemia-inducible secreted endoplasmic reticulum stress response protein in the heart. Circ Res 103: 1249–1258, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor RP, Benjamin IJ. Small heat shock proteins: a new classification scheme in mammals. J Mol Cell Cardiol 38: 433–444, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tissier R, Berdeaux A, Ghaleh B, Couvreur N, Krieg T, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Making the heart resistant to infarction: how can we further decrease infarct size? Front Biosci 13: 284–301, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verschuure P, Croes Y, van den IPR, Quinlan RA, de Jong WW, Boelens WC. Translocation of small heat shock proteins to the actin cytoskeleton upon proteasomal inhibition. J Mol Cell Cardiol 34: 117–128, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zechner D, Craig R, Hanford DS, McDonough PM, Sabbadini RA, Glembotski CC. MKK6 activates myocardial cell NF-kappaB and inhibits apoptosis in a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent manner. J Biol Chem 273: 8232–8239, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou Q, Lam PY, Han D, Cadenas E. c-Jun N-terminal kinase regulates mitochondrial bioenergetics by modulating pyruvate dehydrogenase activity in primary cortical neurons. J Neurochem 104: 325–335, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]