Abstract

Midthoracic spinal cord injury is associated with ventricular arrhythmias that are mediated, in part, by enhanced cardiac sympathetic activity. Furthermore, it is well known that sympathetic neurons have a lifelong requirement for nerve growth factor (NGF). NGF is a neurotrophin that supports the survival and differentiation of sympathetic neurons and enhances target innervation. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that paraplegia is associated with an increased cardiac NGF content, sympathetic tonus, and susceptibility to ischemia-induced ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Intact and paraplegic (6–9 wk posttransection, T5 spinal cord transection) rats were instrumented with a radiotelemetry device for recording arterial pressure, temperature, and ECG, and a snare was placed around the left main coronary artery. Following recovery, the susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias (coronary artery occlusion) was determined in intact and paraplegic rats. In additional groups of matched intact and paraplegic rats, cardiac nerve growth factor content (ELISA) and cardiac sympathetic tonus were determined. Paraplegia, compared with intact, increased cardiac nerve growth factor content (2,146 ± 286 vs. 180 ± 36 pg/ml, P < 0.05) and cardiac sympathetic tonus (154 ± 4 vs. 68 ± 4 beats/min, P < 0.05) and decreased the ventricular arrhythmia threshold (3.6 ± 0.2 vs. 4.9 ± 0.2 min, P < 0.05). Thus altered autonomic behavior increases the susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias in paraplegic rats.

Keywords: cardiovascular risks, arrhythmia

our laboratory recently documented that T5 spinal cord transection (T5X) increased the susceptibility to ischemia-reperfusion-induced sustained ventricular tachycardia (25). The increased susceptibility to the life-threatening arrhythmia was prevented with cardiac β1-adrenergic receptor blockade, documenting that increased sympathetic activity mediates, in part, the increased risk. Furthermore, it is well known that sympathetic neurons have a lifelong requirement for nerve growth factor (NGF). NGF is a neurotrophin that supports the survival and differentiation of sympathetic neurons and enhances target innervation (22). For example, cardiac NGF originates from the target tissue (e.g., myocardium) and is transported via sympathetic fibers back to cell bodies in the stellate ganglia, as well as to sympathetic preganglionic neurons located in the intermediate zone of spinal cord thoracic segments T1–5. In adult animals, NGF is critical in regulating the density of cardiac sympathetic innervation. A deficiency of NGF causes the loss of sympathetic fibers, whereas excessive amounts of NGF cause hyperinnervation (13, 15). Increases in NGF due to cardiac dyssynchrony (abnormal electrical conduction with discoordinate contraction), disease, or injury can produce adverse sympathetic remodeling (5). Importantly, myocardial damage and cardiac dyssynchrony, related to calcium overload, begins as early as 15 min after spinal cord injury in humans and animals (38). Thus individuals with spinal cord injury may have increased myocardial NGF content and cardiac sympathetic hyperinnervation. Furthermore, these neuroplastic changes associated with spinal cord injury may increase the susceptibility to ischemia-induced ventricular arrhythmias.

Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that T5X increases cardiac NGF content, cardiac sympathetic tonus (ST), and the susceptibility to the clinically relevant ischemia-induced sustained ventricular tachycardia. We studied conscious, chronically instrumented rats to negate the confounding effects of anesthetic agents and surgical trauma, as well as to avoid the complications associated with isolated hearts, since isolation and denervation of the heart alter autonomic tone and the physiological responses to coronary occlusion. The ability of anesthesia to influence the susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias is underrecognized, and there are few studies of ischemia-induced arrhythmias in conscious animals (17).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Surgical Procedures

Experimental procedures and protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Wayne State University and complied with The American Physiological Society's Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals. Fourteen adult Sprague-Dawley male rats [n = 6 T5X and n = 8 matched intact (sham T5X), 6–9 wk posttransection or sham procedure] were used to obtain left ventricular NGF content. An additional 12 matched intact and T5X rats (n = 6/group) were used to obtain cardiac ST and parasympathetic tonus (PT). Finally, an additional 19 matched intact rats (n = 12) and T5X rats (n = 7) were used to determine the ischemia-induced ventricular arrhythmia threshold.

All surgical procedures were performed using aseptic surgical techniques. Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg ip), atropinized (0.05 mg/kg ip), intubated, and prepared for aseptic surgery. Supplemental doses of pentobarbital sodium (10–20 mg/kg ip) were administered if the rat regained the blink reflex or responded during the surgical procedures.

Radiotelemetry implantation.

After anesthesia was induced, a telemetry device (Data Sciences International PhysioTel C50-PXT; pressure, temperature, and electrocardiogram) was implanted in all rats, as previously described (25), and a catheter was placed in the intraperitoneal (IP) space for the infusion of fluids and drugs. The transmitter body, which contains the thermistor, was placed in the IP space. The pressure sensor of the telemetry device, located within the tip of a catheter, was inserted into the descending aorta for continuous, nontethered recording of pulsatile arterial blood pressure. The electrical leads from the telemetry device were placed in a modified lead II configuration by placing the negative electrode slightly to the right of the manubrium and the positive electrode at the anterior axillary line along the fifth intercostal space. A minimum of 1 wk was allowed for recovery and for the animals to regain their presurgical weight. During the recovery period, the rats were handled, weighed, and acclimatized to the laboratory and investigators.

Spinal cord transection.

After all animals had recovered to their presurgical weight, the rats were anesthetized as described above, intubated, and positioned prone over a thoracic roll that slightly flexed the trunk. The fourth thoracic vertebra was exposed via a midline dorsal incision, and the spinous process and laminae were removed. Two ligatures (6.0 silk) were tightened around the underlying spinal cord between the fifth and sixth thoracic segments, and the spinal cord was completely transected by cutting between the ligatures with scissors. In this way, there was minimal bleeding. Sympathetic innervation to the heart is derived from preganglionic fibers that exit the spinal cord at the first through fourth thoracic levels. Transection between the fifth and sixth thoracic levels of the spinal cord preserves supraspinal control of cardiac sympathetic activity. The completeness of the transection was confirmed by visual inspection of the lesion site. During the acute recovery period (∼10 days), all rats were handled at least six times daily. During these periods, visual inspections and physical manipulations were performed to detect and prevent pressure sores. In addition, the urinary bladder was voided by manual compression, and all animals were weighed. After this acute recovery period, rats required only daily inspection, and the bladders did not require manual compression. At day 7 posttransection, the rats received a motor activity score using criteria described previously (44). The motor activity score was assessed by placing the animal on a paper-covered table and observing spontaneous motor activity for 1 min. Motor scores ranged from 0 to 5. A motor score of 5 indicates normal walking, whereas a score of 0 indicates no weight-bearing or spontaneous voluntary movement in the hindlimbs. All rats had a motor score of 0, which indicates no weight bearing. Upon completion of the studies, the site of the spinal transection was confirmed by autopsy. Intact rats (n = 12) underwent similar surgical procedures; however, the spinal cord was not transected. All rats were allowed to recover at least 5 wk.

Thoracotomy procedures.

After the 5-wk recovery period, the animals were anesthetized as described above, and the hearts were approached via a left thoracotomy through the fourth intercostal space. A coronary artery occluder was made from an atraumatic needle holding 5.0-gauge prolene suture (8720H, Ethicon). The needle and suture were passed around the left main coronary artery 2–3 mm from the origin by inserting the needle into the left ventricular wall under the overhanging left atrial appendage and bringing it out high on the pulmonary conus. The needle was cut from the suture, and the two ends of the suture were passed through a PE-50 polyethylene guide tubing. The guide tubing with the two ends of the suture were then exteriorized and secured at the back of the neck. The tubing was filled with a mixture of Vaseline and mineral oil to prevent a pneumothorax. At least 1 wk was allowed for recovery. During the recovery period, the rats were handled, weighed, and acclimatized to the laboratory and investigators. Three separate surgeries (telemetry, spinal cord transection, and thoracotomy) were performed because the animals recover significantly better than if two major surgeries are conducted during one session.

Experimental Procedures

Cardiac NGF content.

Six to nine weeks post-T5X or sham T5X, rats were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg), and the heart was excised. The right and left ventricular free wall and septum were quickly dissected, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until future analysis.

The left ventricular free wall was pulverized into fine powder using a liquid nitrogen cooled mortar and pestle. Approximately 70 mg of tissue were suspended in ∼100 μl of lysis buffer [137 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH = 8.0), 1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 0.5 mM sodium vanadate]. The samples were homogenized with Kontes Pellet Pestle Micro Grinders (∼30 s), vortexed, and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was diluted 1:20 in DPBS buffer (0.2 g KCl, 8.0 g NaCl, 0.2 g KH2PO4, 1.15 g Na2HPO4, 133 mg CaCl2·2H2O, and 100 mg MgCl2·6H2O per 1 liter doubled-distilled H2O). All samples were stored at −80°C.

The concentration of NGF was determined using Promega's NGF Emax ImmunoAssay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Nunc MaxiSorp Plates (Nunc catalog no. 439454) were incubated with carbonate coating buffer containing polyclonal anti-NGF overnight at 4°C. The next day, the plates were washed 1×, blocked with 1× block and sample buffer for 1 h at room temperature, and washed 1×. Serial dilutions of known amounts of NGF, ranging from 0 to 250 pg/ml, were performed in duplicate for the standard curve. One-hundred microliters of either sample or standard were added to each well in duplicate and incubated for 6 h at room temperature. The wells were then incubated with a secondary monoclonal anti-NGF overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the wells were incubated with anti-rat IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase for 2.5 h at room temperature. Between incubations, the plates were washed 5× (unless otherwise stated). A TMB One solution was used to develop color in the wells for 10 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with the addition of 100 μl/well 1 N HCl. The absorbance was read at 450 nm within 30 min in a Molecular Devices ThermoMax microplate reader with SOFTmax PRO version 3.1 software (Sunnyvale, CA).

Ventricular arrhythmia threshold.

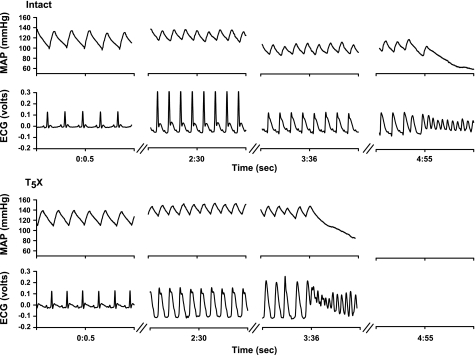

Conscious, unrestrained rats were studied in their home cages for all experiments. Rats were allowed to adapt to the laboratory environment for approximately 1 h to ensure stable hemodynamic conditions. After the stabilization period, beat by beat, steady-state preocclusion hemodynamic variables were recorded over 10–15 s. Subsequently, the left main coronary artery was temporarily occluded by use of the prolene suture. Specifically, acute coronary artery occlusion was performed by pulling up on the suture that was around the left main coronary artery (25). Rapid changes in the ECG (peaked T wave followed by S-T segment elevation) and arterial pressure occur within seconds of pulling on the suture, documenting coronary artery occlusion (Fig. 1). The occlusion was maintained until the onset of ventricular tachycardia. Ventricular tachycardia was defined as sustained ventricular rate (absence of p wave, wide bizarre QRS complex) >1,000 beats/min, with a reduction in arterial pressure <40 mmHg. The ventricular arrhythmia threshold was defined as the time from coronary artery occlusion to sustained ventricular tachycardia, resulting in a reduction in arterial pressure. Normal sinus rhythm appeared upon termination of the occlusion by gently compressing the thorax. Without compressing the thorax, the sustained ventricular tachycardia progresses to ventricular fibrillation. Ventricular fibrillation was defined as a ventricular rhythm without recognizable QRS complex, in which signal morphology changed from cycle to cycle, and for which it was impossible to estimate heart rate (HR). In the event when the animal did not resume normal sinus rhythm, cardioversion was achieved (after the rat lost consciousness) with the use of one shock (10 J) of DC current.

Fig. 1.

One-second analog recordings of mean arterial pressure (MAP) and the electrocardiogram (ECG) in one intact (top) and T5 spinal cord transection (T5X; bottom) rat before coronary artery occlusion (0:0.5), at 2 min 30 s during the occlusion (2:30), and at the onset of sustained ventricular tachycardia and reduction in arterial pressure. The time from coronary artery occlusion to the onset of sustained ventricular tachycardia and reduction in arterial pressure was defined as the ventricular arrhythmia threshold. Coronary artery occlusion was documented by ST segment elevation. Note the higher ST segment elevation in the T5X rat compared with the intact rat at 2:30. T5X rats had a significantly shorter ventricular arrhythmia threshold compared with intact rats. In this example, the sustained ventricular tachycardia and reduction in arterial pressure were produced at 3 min 36 s in the T5X rat compared with 4 min 55 s in the intact rat.

On an alternate day (at least 1 wk apart), the protocol was repeated with cardiac β1-adrenergic receptor blockade (metoprolol 10 mg/kg). Cardiac β1-adrenergic receptor blockade was achieved by infusion of the specific β1-adrenergic receptor antagonist metoprolol into the IP catheter. Ten minutes after metoprolol administration, the ventricular arrhythmia threshold was determined as described above. A crossover design, control and cardiac β1-adrenergic receptor blockade, was used to prevent an order effect. Specifically, the order of the protocols, control and β1-adrenergic receptor blockade, was randomized. Using this randomized design, one-half the rats received the coronary occlusion first with β-blockade, and one-half without.

Cardiac ST and PT.

Two randomized trials were required to determine cardiac ST and PT. Conscious, unrestrained rats were again studied in their home cages (∼13,350 cm3) for all experiments. On the day of the experiment, rats were brought into the laboratory and allowed to adapt to the environment for approximately 1 h to ensure stable hemodynamic conditions. After the stabilization period, beat by beat, steady-state hemodynamic variables were recorded over 10–15 s. Subsequently, the HR and arterial pressure responses to cardiac autonomic sympathetic and parasympathetic blockade (β1-adrenergic and muscarinic-cholinergic receptor blockade) were determined. Drug doses for the sympathetic and parasympathetic antagonists were calculated relative to the animal's body weight on each experimental day. Cardiac muscarinic-cholinergic receptor blockade was achieved by infusion of the nonspecific muscarinic-cholinergic receptor antagonist atropine methyl bromide [methylatropine (MA) 3 mg/kg] through the IP catheter. Because the HR response to MA reached its peak in 10–15 min, this time interval was standardized before the HR measurement. Cardiac β1-adrenergic receptor blockade was achieved by infusion of the specific β1-adrenergic receptor antagonist metoprolol (MT, 10mg/kg) into the IP catheter. MT was infused 15 min after MA, and again the HR response was measured after 15 min. The entire data collection took ∼2 h. At the end of the experiment, the rats were returned to their housing facilities. On an alternate day (>48 h), trial 2 was conducted. Rats were treated identically as described in trial 1, except that the order of blockade was reversed. Intrinsic HR (HRI) was considered to be the HR after complete cardiac autonomic blockade (muscarinic-cholinergic and β1-adrenergic receptor blockades). ST was calculated as HRM − HRI and PT as HRβ − HRI, where HRM is HR after muscarinic-cholinergic receptor blockade and HRβ is HR after β1-adrenergic receptor blockade.

Determination of ischemic zone and infarction.

After the experiments, the rats were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg). To determine the size of the ischemic zone, the heart was excised with the occluder intact and perfused via the aorta with 30 ml of 0.9% saline to wash out the blood. Subsequently, the left main coronary artery was occluded by tying the suture. Evans Blue dye (100 μl, 0.5%) was perfused via the aorta, allowing the dye to infuse into the nonischemic area of the heart, leaving the ischemic regions unstained. The heart was trimmed, leaving only the right and left ventricles, rinsed to remove the excess blue dye, and weighed. The heart was trimmed again, leaving only the ischemic region. The weight of the ischemic zone was expressed as percentage of total ventricular weight. There were no differences in the ischemic zone between the two groups (54 ± 1.5 vs. 58 ± 4%).

To determine if the occlusion produced a myocardial infarction, the heart was sliced transversally into ∼1.0 mm sections and incubated in a 1% TTC solution (2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride; Sigma) at 37°C for 20 min. The heart sections were placed between two glass slides and immersed in 10% formalin overnight to enhance the contrast of the stain. TTC staining differentiates viable tissue by reacting with myocardial dehydrogenase enzymes to form a red brick stain. Necrotic tissue, which has lost its dehydrogenase enzymes, does not form a red stain and shows up as pale yellow. This stain has been shown to be a reliable indicator of myocardial infarction (11). Based on the TTC staining, no animal sustained an infarct. It is important to note that the duration of the occlusions used in this study were very short relative to the time required to induce permanent damage. Specifically, it is well documented that a period of transition from reversible to irreversible injury occurs at ∼20 min of normothermic global ischemia in the rat heart (31). In addition, the TTC method is well documented to be valid and reliable weeks after myocardial infarction (36).

Data Analysis

All recordings were sampled at 2 kHz, and the data were expressed as means ± SE. A two-factor ANOVA was used to compare the ventricular arrhythmia threshold in intact and T5X rats in the control and β-adrenergic receptor blockade conditions. A two-factor ANOVA with repeated measures on one factor was used to compare mean arterial blood pressure and HR immediately before the occlusion (control) at 2.5 min of occlusion and just before the onset of sustained ventricular tachycardia (prearrhythmia). Two and one-half minutes was a standardized time point selected to compare identical time points between groups. This was necessary because the ventricular arrhythmia threshold was different between groups. Importantly, no animal experienced tachycardia before 2.5 min of occlusion in the two conditions. Preocclusion and prearrhythmia data were the average of every beat during the last 10–15 s of the period. In addition, a two-factor ANOVA was used to compare ST elevation and rate-pressure product in the control and β-adrenergic receptor blockade conditions. The rate-pressure product, an index of myocardial oxygen demand, was calculated as systolic blood pressure × HR/1,000. The Holm-Sidak method was used as the post hoc analysis for within-group and within-condition pairwise comparisons. It is more powerful than the Tukey and Bonferroni tests and is recommended as the first line procedure for most multiple-comparison testing.

The ECGs were analyzed offline to measure the ST segment elevation (voltage difference between the baseline and J point) and QT interval (interval between the beginning of the Q wave and the end of the T wave) using the ECG analysis software for Chart (ADInstruments). Each segment was inspected visually and, when necessary, adjusted manually by an investigator blinded to the conditions, to assure accurate measurements. In an attempt to correct for HR dependence, we constructed a correction formula using the generic equation, QTc = QT/RRα, which was applied to all the data. Alpha (α) was derived such that plotting the rate-corrected QT interval against RR interval produced a regression line with a slope of zero. This yielded a correction formula of QTc = QT/RR1/7, thus removing the influence of HR on the QT interval. Therefore, all QT intervals in the study were corrected according to this formula.

RESULTS

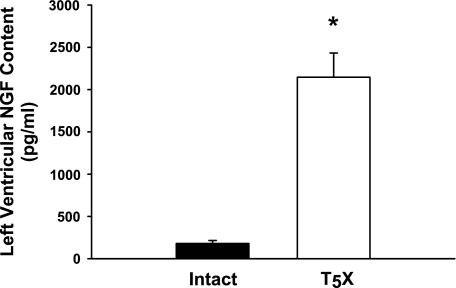

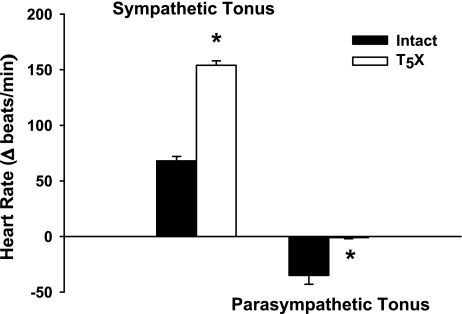

Figure 2 presents left ventricular NGF content for intact and T5X rats. Cardiac NGF content was significantly higher in T5X rats (∼11-fold). Associated with the higher NGF content was a significantly increased cardiac ST and decreased cardiac PT in T5X rats (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Left ventricular nerve growth factor (NGF) content for intact and T5X rats. Cardiac NGF content was significantly higher (∼11-fold) in T5X rats. *P < 0.05, intact vs. T5X.

Fig. 3.

Cardiac sympathetic tonus and cardiac parasympathetic tonus in intact and T5X rats. T5X increased cardiac sympathetic tonus and decreased cardiac parasympathetic tonus. *P < 0.05, intact vs. T5X.

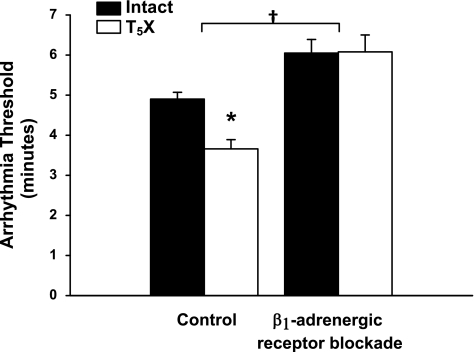

The higher NGF content and increased cardiac ST in T5X rats was associated with a decreased ventricular arrhythmia threshold in the control condition (Fig. 4, significant group × treatment interaction). This difference in the ventricular arrhythmia threshold was abolished following β1-adrenergic receptor blockade (significant treatment effect). These data document that increased sympathetic activity mediates, in part, the increased susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias in T5X rats.

Fig. 4.

Ventricular arrhythmia threshold for intact and T5X rats in the control and β1-adrenergic receptor blockade conditions. The arrhythmia threshold was significantly lower in T5X rats compared with intact rats. β1-Adrenergic receptor blockade increased the threshold, as well as eliminated the difference between intact and T5X rats. *P < 0.05, intact vs. T5X. †P < 0.05, control vs. β1-adrenergic receptor blockade.

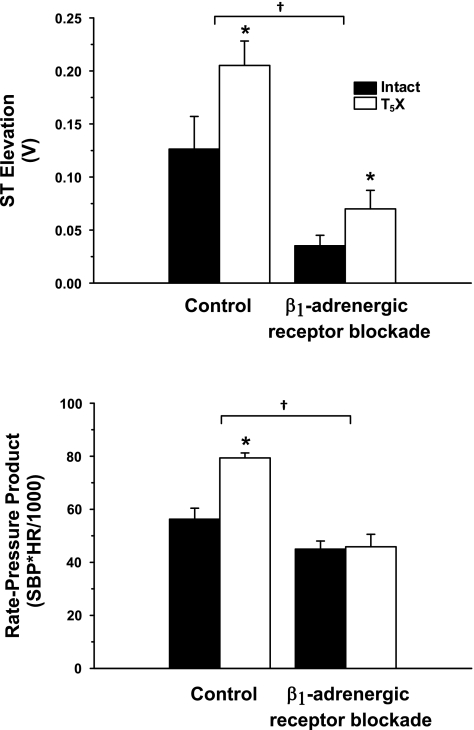

Figure 5 presents the ST-segment elevation (top) and rate-pressure product (bottom) at 2.5 min of occlusion for intact and T5X rats in the control and β1-adrenergic receptor blockade conditions. Although β1-adrenergic receptor blockade lowered ST segment elevation in both intact and T5X rats (significant treatment effect), ST-segment elevation remained significantly higher in T5X rats in both conditions of control and β1-adrenergic receptor blockade (significant group effect). Rate-pressure product was significantly higher in the control condition vs. the β1-adrenergic receptor blockade (significant treatment effect). Post hoc analysis revealed that T5X rats had a higher rate-pressure product in the control condition (significant group × treatment interaction), and this difference was abolished by β1-adrenergic receptor blockade.

Fig. 5.

The ST segment elevation (top) and rate-pressure product (bottom) at 2.5 min of occlusion for intact and T5X rats in the control and β1-adrenergic receptor blockade conditions. ST-segment elevation was significantly higher in T5X rats compared with intact rats in both conditions of control and β1-adrenergic receptor blockade. However, β1-adrenergic receptor blockade reduced ST segment elevation in both intact and T5X groups. T5X rats had a higher rate-pressure product in the control condition compared with intact rats. This difference was abolished by β1-adrenergic receptor blockade. *P < 0.05, intact vs. T5X. †P < 0.05, control vs. β1-adrenergic receptor blockade. SBP, systolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate.

Table 1 presents mean arterial pressure, HR, and the QTc interval under the three conditions of control (immediately before the occlusion) and at 2.5 min of occlusion and prearrhythmia (immediately before the onset of ventricular tachycardia) in intact and T5X rats, with and without β1-adrenergic receptor blockade. There was a significant group effect (P < 0.001) and group × condition interaction (P = 0.018), with no condition effect for mean arterial pressure. Specifically, mean arterial pressure was not different between T5X and intact rats; however, β1-adrenergic receptor blockade lowered mean arterial pressure in the T5X rats during ischemia. In addition, HR was significantly higher in T5X rats [significant group and condition effects (P < 0.001 and P = 0.001, respectively) with no group × condition interaction]. β1-Adrenergic receptor blockade significantly reduced HR in T5X rats; however, HR remained higher compared with intact rats. Finally, there was a significant group effect (P < 0.001), condition effect (P < 0.001), and group × condition interaction (P = 0.009) for QTc. Specifically, the QTc was longer in the T5X rats during the control condition compared with intact rats. Furthermore, β1-blockade shortened the QTc interval below the control levels found in T5X and intact rats. Although post hoc analysis did not reveal differences in the QTc at 2.5 min of occlusion, the QTc in the prearrhythmia condition was significantly longer in T5X rats compared with intact rats and shortened in the presence of β1-adrenergic receptor blockade.

Table 1.

Mean arterial pressure, heart rate, and the corrected QT interval in intact and spinal cord-injured rats, with and without cardiac β-adrenergic receptor blockade under three conditions: control, at 2.5 min of coronary artery occlusion, and before the onset of sustained ventricular tachycardia

| Intact | Intact with β-X | T5X | T5X with β-X | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | ||||

| Control | 115±2 | 117±2 | 121±3 | 116±4 |

| 2.5 min | 124±4 | 116±4 | 129±4 | 95±7†‡ |

| PreArr | 122±4 | 109±3 | 125±5 | 97±9†‡ |

| Heart rate, beats/min | ||||

| Control | 349±6 | 310±3 | 510±16* | 393±7†‡ |

| 2.5 min | 407±23 | 337±18 | 572±9* | 429±13†‡ |

| PreArr | 411±23 | 325±8 | 575±9* | 424±13†‡ |

| Corrected QT interval, ms | ||||

| Control | 91±3 | 80±4 | 107±3* | 74±2†‡ |

| 2.5 min | 105±3 | 94±3 | 112±3 | 100±2 |

| PreArr | 115±3 | 109±2 | 127±5* | 114±3† |

Values are means ± SE. T5X, T5 spinal cord transection; β-X, cardiac β-adrenergic receptor blockade; PreArr, before the onset of sustained ventricular tachycardia.

P < 0.05, T5X vs. intact.

P < 0.05, T5X vs. T5X with β-X.

P < 0.05, T5X with β-X vs. intact.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that T5X (paraplegia) increased cardiac NGF content, cardiac ST, and the susceptibility to clinically relevant ischemia-induced sustained ventricular tachycardia. The major findings of this study include the following. 1) T5X rats have an increased cardiac NGF content (Fig. 2). 2) Associated with the higher NGF content was a significantly increased cardiac ST, HR, and decreased cardiac PT (Fig. 3 and Table 1). 3) The altered autonomic balance was associated with an increased susceptibility to ischemia-induced sustained ventricular tachycardia (Fig. 4). 4) Blocking β1-adrenergic receptor abolished the difference in ventricular arrhythmia threshold between intact and T5X rats, documenting that increased cardiac sympathetic activity mediated, in part, the increased risk. 5) The cardioprotective effect of β1-adrenergic receptor blockade may be due to an anti-ischemic, as well as an anti-arrhythmic mechanism, since β1-adrenergic receptor blockade normalized the elevation in rate pressure product, but not the ST-segment elevation in T5X rats.

The data from the present study confirm previous reports that paraplegia alters cardiac electrophysiology and increases the susceptibility to ventricular tachyarrhythmias induced by programmed electrical stimulation (35), as well as myocardial reperfusion (25), and, importantly, extends these reports by documenting that paraplegia also increases the susceptibility to the clinically relevant ischemia-induced sustained ventricular tachycardia in conscious animals. It is important to note that different mechanisms mediate ischemia-induced, ischemia reperfusion-induced, and programmed electrical stimulation-induced arrhythmias. Furthermore, ischemia is a more common trigger of sudden death than reperfusion (43). In addition, the increased susceptibility to the clinically relevant ischemia-induced sustained ventricular tachycardia was mediated, in part, by enhanced cardiac ST. Finally, the increased ST may be mediated by NGF because levels of NGF expression within innervated tissues corresponds to innervation density (40).

These findings are important because patients with high-level spinal cord injuries prioritize the recovery of autonomic functions, such as cardiovascular and sexual function and bowel and bladder control, above the ability to walk (1). As stated profoundly by Christopher Reeve, “Spinal cord injury is a ferocious assault on the body that leaves havoc in its wake. Paralysis is certainly part of its legacy, but there are other equally devastating consequences including autonomic dysfunction: compromised cardiovascular, bowel, bladder, and sexual function. Treatments and cures for these losses would greatly improve the quality of life for all of us living with spinal cord injury” (September 30, 2004; Ref. 33).

The results from the present study document neural and electrophysiological remodeling following midthoracic spinal cord injury. Specifically, cardiac ST was higher and cardiac PT was lower (neural remodeling) in paraplegic rats compared with intact rats. In addition, the QTc interval was significantly longer before and during ischemia (electrophysiological remodeling) in T5X compared with intact rats. Excessive prolongation of ventricular repolarization (long QT interval) is thought to promote the generation of early afterdepolarizations and may lead to potentially lethal arrhythmias. β-Adrenergic receptor blockade failed to normalize the QTc interval during ischemia in T5X rats. Thus the question arises as to whether or not the neural remodeling mediated the electrophysiological remodeling and increased the susceptibility to ischemia-induced ventricular tachycardia in T5X compared with intact rats. This question merits further investigation.

These results are consistent with earlier work that documented electrophysiological remodeling following midthoracic spinal cord injury. Specifically, spinal cord-injured rats had a significantly lower electrical stimulation threshold to induce ventricular arrhythmias compared with intact rats (35). The intensity of current required to cause a ventricular tachyarrhythmia was 48% lower in spinal cord-injured rats compared with intact rats. Spinal cord-injured rats also had a 35% lower effective refractory period, as well as a shorter atrial-ventricular interval (−25%), sinus node recovery time (−28%), and Wenckebach cycle length (−19%) compared with intact rats. Associated with the cardiac electrophysiological remodeling was a significantly higher resting HR (34). Midthoracic spinal cord injury was also associated with alterations in the abundance of cardiac calcium regulatory proteins. Specifically, spinal cord injury increased the relative protein expression of the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (45%) and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (40%), whereas the relative protein expression of phospholamban was significantly decreased (−28%). These results are consistent with clinical reports documenting alterations in the electrocardiogram of individuals with spinal cord injuries (21, 26).

As stated above, paraplegia increased left ventricular NGF concentration. NGF is expressed in heart and other sympathetic targets (19). The production of NGF in target organs determines the density of innervation by the sympathetic nervous system (18). For example, overexpression of NGF within the heart of transgenic mice causes hyperinnervation (13). Furthermore, peripheral nerve injury results in increased local NGF expression, which facilitates nerve regeneration (10). Accordingly, cardiac ST and HR were higher in T5X rats (Fig. 3 and Table 1). This is an important consideration, because several long-term cohort studies have found resting HR to be a risk factor for mortality from coronary heart disease, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, or all causes (12, 46).

Alterations in HR have also been documented to result in electrical remodeling and increased vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias (8). For example, atrial-ventricular block and bradycardia caused electrical remodeling (45). Rapid HRs also result in electrical remodeling (30). Importantly, HRs are markedly higher in individuals and animals with midthoracic spinal cord injury (34, 35). The electrical remodeling may be mediated, in part, by NGF. Interestingly, animals with T4 spinal cord transection receiving intrathecal anti-NGF antibody did not develop the elevated HRs typically observed after a T4 spinal cord transection (20).

The concept of remodeling (plasticity) is well established with respect to heart muscle; however, the importance of a “rewiring” of cardiac innervation has only recently received attention (42). Specifically, electrical remodeling is a persistent change in the electrophysiological properties of the myocardium in response to a change in rate or activation sequence (23). It is well established that electrical remodeling has profound implications for the susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmias (47). Over time, electrical remodeling alters the expression of sarcolemmal ion channels, which increases the susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmias (27) and increases cardiac mortality. In this context, investigators have recently provided evidence implicating sympathetic nerve sprouting in ventricular arrhythmogenesis and sudden cardiac death (5, 8, 24). These studies document an association between postinjury sympathetic nerve density and susceptibility to life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. For example, hypercholesterolemia, a change in rate or activation sequence, or enhanced sympathetic nerve activity induces proarrhythmic nerve sprouting and sympathetic hyperinnervation, which are associated with dispersion of repolarization, changes in calcium currents, and increased susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias (23, 24, 48). Importantly, myocardial damage and cardiac dyssynchrony, related to calcium overload, begin as early as 15 min after spinal cord injury in humans and animals (38). It is important to note that an association between increased NGF content and ST does not directly prove a causal relationship. However, this association merits future investigation.

It is well established that disturbances in cardiac autonomic balance play a critical role in triggering cardiac arrhythmias. Specifically, reductions in parasympathetic activity or increases in sympathetic activity increase the susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmias (4). The sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system alter cardiac electrophysiology by activating β-adrenergic and muscarinic-cholinergic receptors. β-Adrenergic receptor blockade and enhanced parasympathetic tone are protective against ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death (37). Specifically, adrenergic stimulation results in a reduction of the electrical, ischemic, and reperfusion thresholds to induce ventricular fibrillation, as well as an increase in the likelihood of spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias. β-Adrenergic receptor stimulation may increase the susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias by increasing intracellular cAMP, HR, and atrial-ventricular nodal conduction, as well as shortening atrial and ventricular refractoriness. β-Adrenergic receptor stimulation may also prolong (by increasing current through L-type Ca2+ channels) or shorten the plateau phase of the action potential (by increasing the delayed rectifier current and the chloride current).

In contrast, parasympathetic (vagal) activation increases the ventricular fibrillation threshold (16), protects against reperfusion arrhythmias, and in some patients terminates ventricular tachycardia (14). Parasympathetic activity may be protective, because it hyperpolarizes the cell membrane and flattens the phase 4 pacemaker potentials of the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodal cells (32). Importantly, ST was higher and PT was lower in paraplegic rats (Fig. 3). Furthermore, blocking β-adrenergic receptor abolished the difference in the ventricular arrhythmia threshold between intact and T5X rats, documenting that increased sympathetic activity mediated, in part, the increased risk. Accordingly, differences in cardiac autonomic control in intact and T5X rats altered cardiac electrical stability and contributed to ventricular arrhythmias.

It is important to note that the measures of ST and PT provide only an indirect indication of cardiac autonomic control. However, the role of the autonomic nervous system in regulating HR has been evaluated indirectly by using pharmacological cardiac autonomic blockade by a variety of investigators (7). Results obtained from these studies have been analyzed by a variety of approaches. For example, comparisons have been made among parasympathetic and sympathetic effects and PT and ST. A parasympathetic effect is defined as the difference between resting HR and maximal HR after muscarinic cholinergic receptor blockade. A sympathetic effect is defined as the difference between resting HR and minimal HR after β1-adrenergic receptor blockade (7). These effects are difficult to interpret, because it is impossible to distinguish the direct result of blockade from the indirect result. Specifically, the HR after muscarinic cholinergic receptor blockade (parasympathetic effect) is the result of the direct effect of removal of the parasympathetic influence on the heart, as well as the indirect effect of the unopposed sympathetic influence on the heart in response to blockade of the parasympathetic limb (7). Another potential limitation when using parasympathetic (or sympathetic) effect is that the change in intrinsic HR is not considered. Any change in intrinsic HR would affect the final HR.

To reduce the influence of these two limitations, investigators have used PT and ST (6). Both PT and ST represent the effect of the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems on the heart without the influence of the opposing limb of the autonomic nervous system. By using ST and PT, investigators are also able to account for the difference in intrinsic HR. Finally, the HR responses to autonomic blockers (using procedures identical to the procedures used in this study) are significantly associated with HR at rest, during exercise, and after exercise (6).

We used ST segment shifts and double product (rate-pressure product, Fig. 5) as an index of the severity of myocardial ischemia (2). ST segment elevation and rate-pressure product were significantly greater in T5X vs. intact rats, and β1-adrenergic receptor blockade normalized rate-pressure product but not ST segment elevation in T5X rats. In addition, HR was significantly higher in T5X rats compared with intact rats and was not normalized following β1-adrenergic receptor blockade. Taken together, these data suggest that the higher level of cardiac sympathetic activity in T5X rats, as well as other mechanisms, increased the susceptibility to sustained ventricular tachycardia.

It is clear that ventricular arrhythmias, induced by coronary artery occlusion, cannot be studied in humans. Furthermore, many factors, such as a healed infarct, hypertrophy, heart failure, etc., influence ischemic-induced arrhythmias. Thus it seems prudent to study a variety of different species reflecting the range of clinical profiles. Rodent models provide a number of advantages. For example, the rat does not have collateral blood flow. Thus coronary occlusion in the rat results in reproducible ischemic zones. This is important, because the size of the ischemic area determines the frequency of ventricular arrhythmias. For example, the dog has a large variation in preexisting collateral flow, and, depending on the degree of collateral flow, the incidence of arrhythmias may vary from zero to 100% after occlusion of a major coronary artery (28).

In addition, there exists an extensive biochemical and physiological database, from investigators around the world, for the inexpensive, readily available rat. For example, we have produced arrhythmias electrically (35) and with coronary artery occlusion (25) in chronically instrumented, conscious rats. Furthermore, the rat has qualitatively similar responses, compared with other species, in terms of drug-induced (39), electrically induced (35), and occlusion-induced (25) arrhythmias (9). Bergey and colleagues (3) concluded that rat, pig, and dog models of myocardial ischemia are qualitatively similar.

Conclusion

Coronary artery occlusion is the leading cause of death in industrially developed countries. The majority of these deaths result from tachyarrhythmias that culminate in ventricular fibrillation. It is well documented that the autonomic nervous system modulates cardiac electrophysiology and that abnormalities of autonomic function can increase the risk of ventricular arrhythmias. Specifically, decreased parasympathetic activity and increased sympathetic activity contribute to cardiac arrhythmias and increase the susceptibility to ventricular fibrillation (4). Importantly, autonomic control of the cardiovascular system is abnormal and unstable after spinal cord injury.

Cardiovascular disease is a growing concern for individuals with spinal cord injury. In fact, the prevalence of coronary artery disease in individuals with paraplegia is much higher than in the general population (41). Furthermore, morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease exceed that caused by renal and pulmonary complications, the primary cause of mortality in previous decades (29). In fact, spinal cord injury increases the susceptibility to programmed electrical stimumlation-induced (35), reperfusion-induced, (25) and ischemic-induced ventricular arrhythmias. The increased susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias may be mediated, in part, by NGF-induced cardiac sympathetic hyperinnervation.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-88615.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson KD Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma 21: 1371–1383, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baller D, Bretschneider HJ, Hellige G. A critical look at currently used indirect indices of myocardial oxygen consumption. Basic Res Cardiol 76: 163–181, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergey JL, Nocella K, McCallum JD. Acute coronary artery occlusion-reperfusion-induced arrhythmias in rats, dogs and pigs: antiarrhythmic evaluation of quinidine, procainamide and lidocaine. Eur J Pharmacol 81: 205–216, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billman GE In-vivo models of arrhythmias: a canine model of sudden cardiac death. In: Practical Methods in Cardiovascular Research. Berlin: Springer, 2005, p. 111–128.

- 5.Cao JM, Chen LS, KenKnight BH, Ohara T, Lee MH, Tsai J, Lai WW, Karagueuzian HS, Wolf PL, Fishbein MC, Chen PS. Nerve sprouting and sudden cardiac death. Circ Res 86: 816–821, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandler MP, DiCarlo SE. Acute exercise and gender alter cardiac autonomic tonus differently in hypertensive and normotensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 274: R510–R516, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen CY, DiCarlo SE. Endurance exercise training-induced resting bradycardia: a brief review. Sports Med Training Rehab 8: 37–77, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen PS, Chen LS, Cao JM, Sharifi B, Karagueuzian HS, Fishbein MC. Sympathetic nerve sprouting, electrical remodeling and the mechanisms of sudden cardiac death. Cardiovasc Res 50: 409–416, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis MJ, MacLeod BA, Walker MJ. Models for the study of arrhythmias in myocardial ischaemia and infarction: the use of the rat. J Mol Cell Cardiol 19: 399–419, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derby A, Engleman VW, Frierdich GE, Neises G, Rapp SR, Roufa DG. Nerve growth factor facilitates regeneration across nerve gaps: morphological and behavioral studies in rat sciatic nerve. Exp Neurol 119: 176–191, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishbein MC, Meerbaum S, Rit J, Lando U, Kanmatsuse K, Mercier JC, Corday E, Ganz W. Early phase acute myocardial infarct size quantification: validation of the triphenyl tetrazolium chloride tissue enzyme staining technique. Am Heart J 101: 595–600, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenland P, Daviglus ML, Dyer AR, Liu K, Huang CF, Goldberger JJ, Stamler J. Resting heart rate is a risk factor for cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality. The Chicago Heart Association Detection Project In Industry. Am J Epidemiol 149: 853–862, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassankhani A, Steinhelper ME, Soonpaa MH, Katz EB, Taylor DA, Andrade-Rozental A, Factor SM, Steinberg JJ, Field LJ, Federoff HJ. Overexpression of NGF within the heart of transgenic mice causes hyperinnervation, cardiac enlargement, and hyperplasia of ectopic cells. Dev Biol 169: 309–321, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hess DS, Hanlon T, Scheinman M, Budge R, Desai J. Termination of ventricular tachycardia by carotid sinus massage. Circulation 65: 627–633, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ieda M, Fukuda K, Hisaka Y, Kimura K, Kawaguchi H, Fujita J, Shimoda K, Takeshita E, Okano H, Kurihara Y, Kurihara H, Ishida J, Fukamizu A, Federoff HJ, Ogawa S. Endothelin-1 regulates cardiac sympathetic innervation in the rodent heart by controlling nerve growth factor expression. J Clin Invest 113: 876–84, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kent KM, Smith ER, Redwood DR, Epstein SE. Electrical stability of acutely ischemic myocardium. Influences of heart rate and vagal stimulation. Circulation 47: 291–298, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinoshita K, Hearse DJ, Braimbridge MV, Manning AS. Ischemia- and reperfusion-induced arrhythmias in conscious rats–studies with prazosin and atenolol. Jpn Circ J 52: 1384–1394, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korsching S, Thoenen H. Nerve growth factor in sympathetic ganglia and corresponding target organs of the rat: correlation with density of sympathetic innervation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 80: 3513–3516, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korsching S, Thoenen H. Developmental changes of nerve growth factor levels in sympathetic ganglia and their target organs. Dev Biol 126: 40–46, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krenz NR, Meakin SO, Krassioukov AV, Weaver LC. Neutralizing intraspinal nerve growth factor blocks autonomic dysreflexia caused by spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 19: 7405–7414, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehmann KG, Shandling AH, Yusi AU, Froelicher VF. Altered ventricular repolarization in central sympathetic dysfunction associated with spinal cord injury. Am J Cardiol 63: 1498–1504, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levi-Montalcini R The nerve growth factor: its role in growth, differentiation and function of the sympathetic adrenergic neuron. Prog Brain Res 45: 235–258, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Libbus I, Rosenbaum DS. Remodeling of cardiac repolarization: mechanisms and implications of memory. Card Electrophysiol Rev 6: 302–310, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu YB, Wu CC, Lu LS, Su MJ, Lin CW, Lin SF, Chen LS, Fishbein MC, Chen PS, Lee YT. Sympathetic nerve sprouting, electrical remodeling, and increased vulnerability to ventricular fibrillation in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Circ Res 92: 1145–1152, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lujan HL, DiCarlo SE. T5 spinal cord transection increases susceptibility to reperfusion-induced ventricular tachycardia by enhancing sympathetic activity in conscious rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H3333–H3339, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcus RR, Kalisetti D, Raxwal V, Kiratli BJ, Myers J, Perkash I, Froelicher VF. Early repolarization in patients with spinal cord injury: prevalence and clinical significance. J Spinal Cord Med 25: 33–38, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medina-Ravell VA, Lankipalli RS, Yan GX, Antzelevitch C, Medina-Malpica NA, Medina-Malpica OA, Droogan C, Kowey PR. Effect of epicardial or biventricular pacing to prolong QT interval and increase transmural dispersion of repolarization: does resynchronization therapy pose a risk for patients predisposed to long QT or torsade de pointes? Circulation 107: 740–746, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meesmann W Early arrhythmias and primary ventricular fibrillation after acute myocardial ischaemia in relation to preexisting coronary collaterals. In: Early Arrhythmias Resulting from Myocardial Ischaemia, edited by Parratt J. London: Macmillan, 1982, p. 93–112.

- 29.Myers J, Lee M, Kiratli J. Cardiovascular disease in spinal cord injury: an overview of prevalence, risk, evaluation, and management. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 86: 142–152, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pak PH, Nuss HB, Tunin RS, Kaab S, Tomaselli GF, Marban E, Kass DA. Repolarization abnormalities, arrhythmia and sudden death in canine tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 30: 576–584, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmer BS, Hadziahmetovic M, Veci T, Angelos MG. Global ischemic duration and reperfusion function in the isolated perfused rat heart. Resuscitation 62: 97–106, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prystowsky EN, Grant AO, Wallace AG, Strauss HC. An analysis of the effects of acetylcholine on conduction and refractoriness in the rabbit sinus node. Circ Res 44: 112–120, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reeve C Dedication. In: Progress in Brain Research, Autonomic Dysfunction after Spinal Cord Injury, edited by Weaver L and Polosa C. The Netherlands: Elsevier Science, 2005, p. ix.

- 34.Rodenbaugh DW, Collins HL, DiCarlo SE. Paraplegia differentially increases arterial blood pressure related cardiovascular disease risk factors in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Brain Res 980: 242–248, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodenbaugh DW, Collins HL, Nowacek DG, DiCarlo SE. Increased susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias is associated with changes in Ca2+ regulatory proteins in paraplegic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H2605–H2613, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santos L, Mello AF, Antonio EL, Tucci PJ. Determination of myocardial infarction size in rats by echocardiography and tetrazolium staining: correlation, agreements, and simplifications. Braz J Med Biol Res 41: 199–201, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Napolitano C. Role of the autonomic nervous system in sudden cardiac death. In: Sudden Cardiac Death, edited by Josephson ME. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Scientific, 1993, p. 16–37.

- 38.Sharov VG, Galakhin KA. [Myocardial changes after spinal cord injuries in humans and experimental animals]. Arkh Patol 46: 17–20, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teplitz L, Igic R, Berbaum ML, Schwertz DW. Sex differences in susceptibility to epinephrine-induced arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 46: 548–555, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thoenen H, Bandtlow C, Heumann R. The physiological function of nerve growth factor in the central nervous system: comparison with the periphery. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 109: 145–78, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas T, Haase N, Rosamond W, Howard V, Rumsfeld J, Manolio T, Zheng Z, Flegal K, O'Donnell C, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, Goff DJ, Hong Y, Members of the Statistics Committee, and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee, Adams R, Friday G, Furie K, Gorelick P, Kissela B, Marler J, Meigs J, Roger V, Sidney S, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wilson M, and Wolf P. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circ 113: e85–e151, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verrier RL, Kwaku KF. Frayed nerves in myocardial infarction: the importance of rewiring. Circ Res 95: 5–6, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verrier R Autonomic substrates for arrhythmias. Progress in Cardiology 1: 65–85, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Von Euler M, Akesson E, Samuelsson EB, Seiger A, Sundstrom E. Motor performance score: a new algorithm for accurate behavioral testing of spinal cord injury in rats. Exp Neurol 137: 242–254, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vos MA, de Groot SH, Verduyn SC, van der Zande J, Leunissen HD, Cleutjens JP, van Bilsen M, Daemen MJ, Schreuder JJ, Allessie MA, Wellens HJ. Enhanced susceptibility for acquired torsade de pointes arrhythmias in the dog with chronic, complete AV block is related to cardiac hypertrophy and electrical remodeling. Circulation 98: 1125–1135, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wannamethee G, Shaper AG, Macfarlane PW. Heart rate, physical activity, and mortality from cancer and other noncardiovascular diseases. Am J Epidemiol 137: 735–748, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wijffels MC, Kirchhof CJ, Dorland R, Allessie MA. Atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation. A study in awake chronically instrumented goats. Circulation 92: 1954–1968, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou S, Chen LS, Miyauchi Y, Miyauchi M, Kar S, Kangavari S, Fishbein MC, Sharifi B, Chen PS. Mechanisms of cardiac nerve sprouting after myocardial infarction in dogs. Circ Res 95: 76–83, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]