Abstract

Background

Bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are hypothesized to share some genetic background.

Methods

In a two-phase study, we evaluated the effect of five promising candidate genes for psychotic disorders, DAOA, COMT, DTNBP1, NRG1, and AKT1, on bipolar spectrum disorder, psychotic disorder, and related cognitive endophenotypes in a Finnish family-based sample ascertained for bipolar disorder.

Results

In initial screening of 362 individuals from 63 families, we found only marginal evidence for association with the diagnosis-based dichotomous classification. Those associations did not strengthen when we genotyped the complete sample of 723 individuals from 180 families. We observed a significant association of DAOA variants rs3916966 and rs2391191 with visuospatial ability (Quantitative Transmission Disequilibrium Test [QTDT]; p = 4 × 10−6 and 5 × 10−6, respectively) (n = 159) with the two variants in almost complete linkage disequilibrium. The COMT variant rs165599 also associated with visuospatial ability, and in our dataset, we saw an additive effect of DAOA and COMT variants on this neuropsychological trait.

Conclusions

The ancestral allele (Arg) of the nonsynonymous common DAOA variant rs2391191 (Arg30Lys) was found to predispose to impaired performance. The DAOA gene may play a role in predisposing individuals to a mixed phenotype of psychosis and mania and to impairments in related neuropsychological traits.

Key Words: AKT1, bipolar disorder, COMT, DAOA, DTNBP1, G72, neuropsychological trait, NRG1

Bipolar disorder (BPD) is a severe mental disorder characterized by alternating episodes of depression and mania (bipolar type I [BPD-I]) or hypomania (bipolar type II [BPD-II]). Certain cognitive impairments such as poor executive functioning and verbal memory have been related to disease susceptibility (1). Despite being considered distinct clinical disorders, BPD and schizophrenia share many clinical features and treatment approaches. Sixty percent of BPD-I patients have psychotic symptoms during their lifetime (2). Bipolar disorder and schizophrenia co-segregate in many pedigrees (3), which suggest a shared genetic etiology of these two disorders at least to some extent.

In our previous study, we found evidence for contribution of distinct variants of the disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) gene to features of bipolar spectrum and psychotic disorders in Finnish families ascertained for BPD (4). We screened the same set of BPD families for several promising candidate genes for psychotic disorders: d-amino acid oxidase activator (DAOA or G72) (5), catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) (6), dystrobrevin binding protein 1 (dysbindin or DTNBP1) (7), neuregulin 1 (NRG1) (8), and v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 (AKT1) (9). Except for AKT1, these genes have been reported to associate with various neuropsychological traits within affected individuals or healthy control subjects (Supplement 1). We evaluated the effects of variations in these genes both on clinical diagnosis of bipolar spectrum disorder or psychotic disorder, as well as on cognitive functions considered as endophenotypes (or intermediate traits) for these disorders (10).

Methods and Materials

Study Sample

The study sample includes 723 individuals from 180 families (4) (Table 1); neuropsychological test data were available altogether for 159 individuals from 65 of the families (11) (Table 1). Ascertainment strategy and sample collection are described in Supplement 2. The study was approved by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and the Ethical Committee of the National Public Health Institute.

Table 1.

Number of Individuals in Phase I and Phase II of the Study and the Total Number of Familial Cases

| Phase I |

Phase II |

Familial Casesa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | ||

| Affected | 78 (32) | 89 (30) | 65 (4) | 84 (14) | 258 |

| Bipolar spectrum disorderb | 59 (29) | 68 (24) | 50 (4) | 50 (9) | 173 |

| Psychotic disorderc | 66 (27) | 65 (25) | 51 (4) | 69 (12) | 212 |

| In both categoriesd | 47 (24) | 44 (19) | 36 (4) | 35 (7) | 127 |

| Other mental disordere | 22 (14) | 12 (8) | 5 (2) | 7 (3) | 45 |

| Unaffected | 92 (29) | 69 (21) | 116 (1) | 84 (1) | 241 |

| Total Genotyped | 192 (75) | 170 (59) | 186 (7) | 175 (18) | 544 |

The number of neuropsychologically tested individuals is shown in parentheses.

BPD-I, bipolar disorder type I; BPD-II, bipolar disorder type II; NOS, not otherwise specified.

The familial cases are from 118 families with more than one affected individual.

Contains BPD-I (n = 214), BPD-II (n = 5), bipolar disorder NOS (n = 6), and cyclothymia (n = 2) cases.

Contains BPD-I with intermittent psychotic features (n = 162), psychotic depression (n = 15), schizophrenia (n = 14), schizoaffective disorder (n = 51), and psychotic NOS (n = 9). Numbers are from the whole sample.

Overlap between bipolar spectrum and psychotic disorder categories.

Contains depression, alcohol-, related disorders and delusional, adjustment, dysthymic, and panic disorders.

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Selection and Genotyping

We selected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from published findings (5-9) and from the public SNP database, dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Genotyping was done with homogeneous mass extension using the MassARRAY System (Sequenom, San Diego, California) in multiplexes of two to six SNPs. The COMT variants were genotyped by microarray-based allele-specific primer extension method (12). Genotyping was performed in two phases. Phase I was an initial screening involving 362 individuals from 63 families. In phase II, we examined an additional 361 individuals from 117 families.

Statistical Analysis

Association analyses using dichotomized diagnostic classes (bipolar spectrum disorder and psychotic disorder) were performed by haplotype relative risk (HRR) test of the ANALYZE package (13) for two-point analyses and by FBAT (14) for haplotype analyses. Unaffected family members and individuals with other mental disorders were coded as unknown. Analyses were done using two different sample sets, the first including all individuals genotyped and the second including only familial cases, defined as cases from families with two or more affected members. We used the Quantitative Transmission Disequilibrium Test (QTDT) software package (15) with the polygenic variance component option and performed association analyses of quantitative traits with the total association model assuming no population stratification. Age, gender, and presence of psychosis (16) were used as covariates. Statistical comparisons of the results in different genotyped groups and diagnostic categories were analyzed by SPSS 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Interaction analysis was done by logistic regression backward stepwise model.

Results

We initially screened 51 SNPs of the selected genes (Supplement 3) in 362 individuals from 63 families (Table 1). The most significant association of dichotomized phenotype was obtained for COMT variant rs165599 with bipolar spectrum disorder (HRR; p = .003) (Supplement 3). Adjacent 2-SNP haplotype analysis showed no evidence for association with either bipolar spectrum or psychotic disorder (Supplement 4). Several DAOA variants were associated with neuropsychological traits (Supplement 5). The strongest associations were seen between DAOA variants rs3916966 and rs2391191 (Arg30Lys) and visuospatial ability assessed with the Block Design test (p = .0006 and p =.0008, respectively).

We focused our analysis on DAOA and COMT and genotyped all 723 individuals from 180 families using six DAOA variants (rs3916966, rs2391191, rs2153674, rs701567, rs778326, and rs954580) and two COMT variants (rs165599 and rs4680, also known as valine [Val]158 methionine [Met]).

In the complete sample, the COMT variant rs4680 was the only variant that associated with bipolar spectrum disorder in the complete sample (Table 2). In the familial sample, both rs4680 and rs165599 showed suggestive evidence of association with bipolar spectrum disorder. D-amino acid oxidase activator (DAOA) variants rs701567 and rs778326 were suggestively associated with psychotic disorder in the familial sample. For both genes, analysis of 2-SNP haplotypes yielded no further evidence of association (data not shown).

Table 2.

Association Between Single SNP and Disease Status in Phase I, Combined Phase I and Phase II, and Familial Cases Using HRR Analysis

| Bipolar Spectrum Disorder |

Psychotic Disorder |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I (62 Families) | Phase I + II (154 Families) | Familial Casesa (99 Families) | Phase I (57 Families) | Phase I + II (144 Families) | Familial Casesa (102 Families) | |

| DAOA | ||||||

| rs3916966 | .696 | .966 | .906 | .843 | .839 | .616 |

| rs2391191 | .889 | .913 | .735 | .87 | .891 | .349 |

| rs2153674 | .072 | .353 | .095 | .066 | .700 | .233 |

| rs701567 | .670 | .593 | .407 | .278 | .133 | .031 |

| rs778326 | .025 | .111 | .024 | .010 | .186 | .018 |

| rs954580 | .040 | .107 | .052 | .049 | .565 | .252 |

| COMT | ||||||

| rs4680 | .085 | .046 | .020 | .340 | .072 | .149 |

| rs165599 | .003 | .829 | .035 | .015 | .396 | .103 |

COMT, catechol-O-methyl transferase; DAOA, d-amino acid oxidase activator; HRR, haplotype relative risk; SNP, single nucleoide polymorphism.

Familial cases include only families that contain at least two affected individuals.

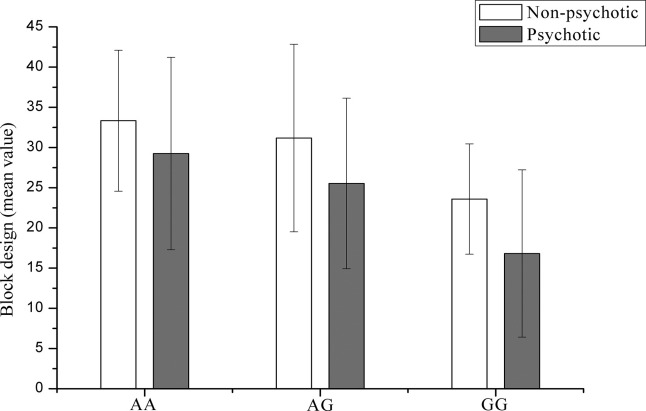

Analysis of the full study sample strengthened the previously observed association between DAOA variants rs3916966 and rs2391191 (Arg30Lys) and visuospatial ability (Table 3). These two variants are in almost perfect linkage disequilibrium (r2 = .98). Visuospatial performance differed significantly between the Arg and Lys genotype groups of rs2391191, with the worst performance observed in individual homozygotes for the ancestral G (Arg) allele (Table 4, Figure 1). All study subjects performing above the average, i.e., achieving over 40 points in the Block Design test (n = 27), were either homozygous or heterozygous for the A (Lys) allele.

Table 3.

Association Between Neuropsychological Traits and Candidate Gene Variants Genotyped in the Combined Sample Using QTDT Analysis

|

DAOA |

COMT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychological Trait | rs3916966 | rs2391191 | rs2153674 | rs701567 | rs954580 | rs4680 | rs165599 |

| General Intellectual Functioning (WAIS-R) | |||||||

| General ability (Vocabulary) | .0015 | .0002 | .0086 | .0083 | .0051 | .1381 | .1801 |

| Abstraction (Similarities) | .0010 | .0003 | .0063 | .0173 | .1428 | .1191 | .2103 |

| Psychomotor speed (Digit Symbol) | .0013 | .0034 | .0953 | .0125 | .2591 | .0986 | .0051 |

| Visuospatial ability (Block Design) | 4.00E-06a | 5.00E-06a | .0638 | .0108 | .0392 | .0191 | .0007 |

| Attention, Working Memory (WMS-R) | |||||||

| Auditory attention (Digit Span forward) | .0091 | .0088 | .0991 | .1948 | .0724 | .2769 | .5932 |

| Verbal working memory (Digit Span backward) | .0298 | .0213 | .1089 | .4111 | .6239 | .4017 | .8425 |

| Visual attention (Visual Span forward) | .1899 | .1374 | .6787 | .2073 | .2443 | .8875 | .9947 |

| Visual working memory (Visual Span backward) | .7120 | .5995 | .9652 | .7439 | .5356 | .7039 | .4952 |

| Verbal and Visual Memory (WMS-R) | |||||||

| Immediate verbal memory (Logical Memory I) | .1176 | .0602 | .4636 | .7139 | .7698 | .9536 | .8925 |

| Delayed verbal memory (Logical Memory II) | .1076 | .0638 | .8161 | .5091 | .4862 | .5853 | .4035 |

| Immediate visual memory (Visual Reproduction I) | .0047 | .0047 | .2174 | .2841 | .1352 | .0628 | .1468 |

| Delayed visual memory (Visual Reproduction II) | .0005 | .0010 | .2658 | .1316 | .2061 | .1200 | .2613 |

| Verbal Learning and Memory (CVLT) | |||||||

| Free short delay recall | .0032 | .0024 | .0537 | .1016 | .1397 | .0891 | .4644 |

| Free long delay recall | .0443 | .0206 | .2987 | .5264 | .7442 | .0054 | .0570 |

| Recognition memory | .0173 | .0079 | .1617 | .4569 | .5709 | .1076 | .4686 |

| Retention | .9571 | .4473 | .4304 | .8079 | .2869 | .0391 | .0016 |

| Executive Functions | |||||||

| Stroop Interference score | .0162 | .0060 | .3567 | .0047 | .3510 | .3090 | .7938 |

| Semantic fluency (COWAT) | .0195 | .0239 | .8410 | .0168 | .3594 | .5887 | .4003 |

| Phonemic fluency (COWAT) | .4183 | .4524 | .0369 | .4284 | .4841 | .6706 | .5438 |

COMT, catechol-O-methyl transferase; COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; DAOA, d-amino acid oxidase activator; WAIS-R, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised; WMS-R, Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised; QTDT, Quantitative Transmission Disequilibrium Test.

p values that remained significant (p < .05) after conservative Bonferroni correction.

Table 4.

The Effect of DAOA Variant rs2391191 and COMT Variant rs165599 on Visuospatial Ability (Block Design), Showing Mean Values of Block Design Test in Cross Table of DAOA rs2391191 and COMT rs165599 Genotypes in All Individuals and in Psychotic and Nonpsychotic Groups

| COMT Variant rs165599 |

DAOA Variant rs2391191 |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

Psychotic |

Nonpsychotic |

|||||||||||||

| AA | AG | GG | Mean (n) | p value | AA | AG | GG | Mean (n) | p value | AA | AG | GG | Mean (n) | p value | |

| CC | 30.6 (7) | 38.1 (8) | 28.2 (5) | 34.1 (22) | .009 | 35.7 (3) | 40.5 (4) | 22.0 (1) | 33.2 (9) | .013 | 39.3 (4) | 35.8 (4) | 29.8 (4) | 34.8 (139) | .252 |

| CT | 32.2 (16) | 26.8 (28) | 23.3 (12) | 28.0 (61) | 34.8 (5) | 22.7 (12) | 23.3 (4) | 25.9 (22) | 30.8 (11) | 30.0 (16) | 23.4 (8) | 29.2 (39) | |||

| TT | 29.5 (20) | 28.1 (37) | 15.6 (16) | 25.7 (73) | 23.1 (8) | 23.9 (16) | 14.0 (11) | 20.9 (36) | 33.7 (12) | 31.2 (21) | 19.0 (5) | 30.4 (37) | |||

| Mean (n) | 31.8 (43) | 28.7 (73) | 20.3 (33) | 29.3 (16) | 25.7 (33) | 16.0 (15) | 33.3 (27) | 31.2 (40) | 23.9 (18) | ||||||

| p value | 2.3E-05 | .003 | .008 | ||||||||||||

The numbers of individuals that belong to a specific genotype group are in parentheses. The mean scores and the p values from one-way ANOVA are shown for each genotype group separately.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; COMT, catechol-O-methyl transferase; DAOA, d-amino acid oxidase activator.

Figure 1.

Block Design test results for DAOA rs2391191 genotype groups. Average values of nonpsychotic individuals (white bars) and individuals with psychotic disorder (gray bars) are shown. Also, the standard deviation bar is shown. DAOA, d-amino acid oxidase activator.

Catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) variant rs165599 associated with visuospatial ability. Individuals homozygous for the G allele had the best test performance among the rs165599 genotype groups. This difference was statistically significant in the full sample and in the psychotic subgroup but not in the nonpsychotic subgroup (Table 4).

As shown in Table 4, individuals homozygous for both the ancestral allele G (Arg) of DAOA variant rs2391191 and the T allele of COMT variant rs165599 performed worse in the Block Design test (mean test score = 15.6) than did subjects homozygous only for the DAOA rs2391191 G allele (mean test score = 24.8) or the COMT rs165599 T allele (mean test score = 28.6). However, backward stepwise logistic regression showed no evidence for significant interaction between the two variants (p = .5 for rs2391191*rs165599). Decreased test performance in the doubly homozygous subjects suggests a minor additive effect of DAOA and COMT variants on visuospatial ability, without evidence for epistasis.

Discussion

D-amino acid oxidase activator (DAOA) is a primate-specific gene encoding mitochondrial protein that promotes mitochondrial fragmentation and dendritic branching (17). D-amino acid oxidase activator (DAOA) may be involved in glutamate signaling (5), which has been shown to have multiple effects on learning and memory (18). Like some other genes encoding mitochondrial proteins in primates, the DAOA gene has evolved rapidly; the open reading frame of the human gene is twice as long as that of the chimpanzee homolog (5).

The strongest finding of our study was the association of a nonsynonymous DAOA variant, rs2391191 (Arg30Lys), with visuospatial ability, which remains significant after a conservative Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (corrected p = .005). In a recent study (19), the Arg allele associated with impairment in immediate and delayed verbal memory. In the present study, this allele showed only a trend for association with verbal memory (p < 0.1), but it predisposed to impairment with many other cognitive traits, most significantly with visuospatial ability. Thus, our data further strengthen the possibility that the Arg30Lys variation might affect cognitive functioning. Interestingly, the Lys allele that associated here with enhanced performance in the tests of general intellectual functioning is found only in humans, suggesting that DAOA might have played a part in the evolution of Homo sapiens when greater cognitive functions developed as the brain increased in size.

Catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) variant rs4680 (Val158Met) associated here nominally with familial bipolar spectrum disorder, but the risk allele (Met) was different from that reported by Shifman et al. (6). Variant rs165599 was also associated with visuospatial ability, with the best test performance seen in individuals homozygous for the C allele. An earlier study showed association of the COMT variant rs165599 with verbal memory in Caucasians (20), but better performance was associated with the T allele. The incoherence in findings on the effect of COMT on neuropsychological performance likely results from a relatively weak effect and the genetic heterogeneity behind these traits.

We found a minor additive effect of DAOA and COMT on visuospatial ability, a finding consistent with the hypothesis that interaction of glutamatergic (DAOA) and dopaminergic (COMT) neurotransmission is fundamental for many cognitive functions, particularly working memory (18). We recognize that all neuropsychological traits assessed in the present study may be state-dependent; however, many of the observed deviations are also found in euthymic BPD patients (1). Furthermore, our finding of association of DAOA with visuospatial ability did not result from an underlying effect of DAOA genotype to other illness-related parameters, such as medication or age of onset (data not shown). While there are no data for visuospatial ability being a good endophenotype for BPD, there is at least one study that showed impaired general intellectual function in relatives of psychotic patients (21). Other DAOA variants also associated weakly with psychotic disorder. The DAOA gene may play a role in predisposing individuals to a mixed phenotype of psychosis and mania and to impairments in related neuropsychological traits. However, further research is necessary to define the effect of DAOA on the complex processes of brain functions.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by The Academy of Finland for TPau (Nr 203425).

We thank all the individuals who participated in this study. Liisa Arala, Minna Suvela, and Sisko Lietola are acknowledged for excellent technical assistance.

All authors reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material cited in this article is available online.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Robinson L.J., Thompson J.M., Gallagher P., Goswami U., Young A.H., Ferrier I.N. A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2006;93:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodwin F.K., Jamison K.R. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. Manic-Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valles V., Van Os J., Guillamat R., Gutierrez B., Campillo M., Gento P. Increased morbid risk for schizophrenia in families of in-patients with bipolar illness. Schizophr Res. 2000;42:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palo O.M., Antila M., Silander K., Hennah W., Kilpinen H., Soronen P. Association of distinct allelic haplotypes of DISC1 with psychotic and bipolar spectrum disorders and with underlying cognitive impairments. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2517–2528. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chumakov I., Blumenfeld M., Guerassimenko O., Cavarec L., Palicio M., Abderrahim H. Genetic and physiological data implicating the new human gene G72 and the gene for D-amino acid oxidase in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13675–13680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shifman S., Bronstein M., Sternfeld M., Pisante-Shalom A., Lev-Lehman E., Weizman A. A highly significant association between a COMT haplotype and schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:1296–1302. doi: 10.1086/344514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Straub R.E., Jiang Y., MacLean C.J., Ma Y., Webb B.T., Myakishev M.V. Genetic variation in the 6p22.3 gene DTNBP1, the human ortholog of the mouse dysbindin gene, is associated with schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:337–348. doi: 10.1086/341750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefansson H., Sigurdsson E., Steinthorsdottir V., Bjornsdottir S., Sigmundsson T., Ghosh S. Neuregulin 1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:877–892. doi: 10.1086/342734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emamian E.S., Hall D., Birnbaum M.J., Karayiorgou M., Gogos J.A. Convergent evidence for impaired AKT1-GSK3beta signaling in schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2004;36:131–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottesman I.I., Gould T.D. The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: Etymology and strategic intentions. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:636–645. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antila M., Tuulio-Henriksson A., Kieseppa T., Soronen P., Palo O.M., Paunio T. Heritability of cognitive functions in families with bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144:802–808. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silander K., Komulainen K., Ellonen P., Jussila M., Alanne M., Levander M. Evaluating whole genome amplification via multiply-primed rolling circle amplification for SNP genotyping of samples with low DNA yield. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2005;8:368–375. doi: 10.1375/1832427054936664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terwilliger J.D., Ott J. A haplotype-based ‘haplotype relative risk’ approach to detecting allelic associations. Hum Hered. 1992;42:337–346. doi: 10.1159/000154096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horvath S., Xu X., Lake S.L., Silverman E.K., Weiss S.T., Laird N.M. Family-based tests for associating haplotypes with general phenotype data: Application to asthma genetics. Genet Epidemiol. 2004;26:61–69. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abecasis G.R., Cardon L.R., Cookson W.O. A general test of association for quantitative traits in nuclear families. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:279–292. doi: 10.1086/302698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keshavan M.S., Rabinowitz J., DeSmedt G., Harvey P.D., Schooler N. Correlates of insight in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kvajo M., Dhilla A., Swor D.E., Karayiorgou M., Gogos J.A. Evidence implicating the candidate schizophrenia/bipolar disorder susceptibility gene G72 in mitochondrial function. Mol Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002052. [published online ahead of print August 7, 2007] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castner S.A., Williams G.V. Tuning the engine of cognition: A focus on NMDA/D1 receptor interactions in prefrontal cortex. Brain Cogn. 2007;63:94–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donohoe G., Morris D.W., Robertson I.H., McGhee K.A., Murphy K., Kenny N. DAOA ARG30LYS and verbal memory function in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:795–796. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burdick K.E., Funke B., Goldberg J.F., Bates J.A., Jaeger J., Kucherlapati R. COMT genotype increases risk for bipolar I disorder and influences neurocognitive performance. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:370–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zinkstok J.R., de Wilde O., van Amelsvoort T.A., Tanck M.W., Baas F., Linszen D.H. Association between the DTNBP1 gene and intelligence: A case-control study in young patients with schizophrenia and related disorders and unaffected siblings. Behav Brain Funct. 2007;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.