Abstract

Chloroplasts of photosynthetic organisms harness light energy and convert it into chemical energy. In several land plants, GOLDEN2-LIKE (GLK) transcription factors are required for chloroplast development, as glk1 glk2 double mutants are pale green and deficient in the formation of the photosynthetic apparatus. We show here that glk1 glk2 double mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana accumulate abnormal levels of chlorophyll precursors and that constitutive GLK gene expression leads to increased accumulation of transcripts for antenna proteins and chlorophyll biosynthetic enzymes. To establish the primary targets of GLK gene action, an inducible expression system was used in combination with transcriptome analysis. Following induction, transcript pools were substantially enriched in genes involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis, light harvesting, and electron transport. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments confirmed the direct association of GLK1 protein with target gene promoters, revealing a putative regulatory cis-element. We show that GLK proteins influence photosynthetic gene expression independently of the phyB signaling pathway and that the two GLK genes are differentially responsive to plastid retrograde signals. These results suggest that GLK genes help to coregulate and synchronize the expression of a suite of nuclear photosynthetic genes and thus act to optimize photosynthetic capacity in varying environmental and developmental conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Photosynthetic organisms rely on the efficient collection of light to drive photochemical reactions and fix inorganic carbon. The photosynthetic apparatus that harvests light comprises a series of multisubunit protein complexes that reside on convoluted, internal chloroplast membranes called thylakoids. Two of these protein complexes, photosystem I (PSI) and photosystem II (PSII), are each composed of a core reaction center surrounded by a peripheral light-harvesting complex called LHCI and LHCII, respectively. The LHC comprises protein-bound chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments that optimize light absorption and transfer excitation energy to additional chlorophylls in the reaction center (Green and Durnford, 1996).

In land plants, the genetic contribution to photosynthesis is shared between the nuclear and plastid genomes (Martin et al., 2002). The genes encoding many of the photosystem reaction center subunits are in the plastid, while those for the LHC proteins reside in the nucleus. The Lhcb gene family encodes members of LHCII, and the Lhca family encodes members of LHCI (Jansson, 1999). While chlorophyll a is distributed throughout the chlorophyll binding subunits of PSI and PSII, chlorophyll b is uniquely bound to LHCs and not to reaction center proteins (Green and Durnford, 1996). There is much evidence suggesting that chlorophyll b is absolutely required for LHC assembly. First, Arabidopsis thaliana mutants lacking chlorophyllide a oxygenase (CAO) are unable to synthesize chlorophyll b and do not accumulate Lhcb1 to Lhcb6 (Espineda et al., 1999). Second, Lhcb proteins only insert into barley (Hordeum vulgare) etioplast membranes in vitro when supplemented with derivatives of chlorophyll b (Kuttkat et al., 1997). Third, CAO is necessary for the import of Lhcb monomers into isolated chloroplasts (Reinbothe et al., 2006). Thus, the concurrent events of Lhcb import, pigment binding, and protein folding mean that assembly of LHCII and chlorophyll biosynthesis are inseparable processes. Since all Lhc genes and all chlorophyll biosynthesis genes reside in the nucleus, it follows that these genes might be coregulated for efficient photosynthetic development. However, few examples of transcription factors that regulate chloroplast biogenesis have been described, and, to our knowledge, none have been shown to coordinate photosystem assembly per se.

Golden2-like (GLK) genes encode GARP nuclear transcription factors (Riechmann et al., 2000) as defined by GOLDEN2 in maize (Zea mays), the Arabidopsis RESPONSE REGULATOR-B proteins, and the PHOSPHATE STARVATION RESPONSE1 protein of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. GLK genes have been implicated in the regulation of chloroplast development in Arabidopsis, Z. mays, and the moss Physcomitrella patens (Rossini et al., 2001; Fitter et al., 2002; Yasumura et al., 2005). In each species examined, GLK genes exist as a homologous pair named GLK1 and GLK2. In moss and Arabidopsis, GLK genes are redundant and functionally equivalent, such that only glk1 glk2 double mutants exhibit a perturbed phenotype (Yasumura et al., 2005; Waters et al., 2008). Arabidopsis double mutants are pale green, and mesophyll cells contain small chloroplasts with sparse thylakoid membranes that fail to form grana. Consistent with the poorly developed chloroplasts, glk1 glk2 mutants exhibit reduced transcript and protein levels for nuclear-encoded photosynthetic genes, especially those associated with chlorophyll biosynthesis and light harvesting (Fitter et al., 2002). Notably, however, a pale-green phenotype and the associated perturbations in chlorophyll biosynthesis and photosystem assembly could potentially result from any number of primary defects in chloroplast biogenesis. As such, the identification of immediate gene targets is necessary to further understand GLK function.

To elucidate the primary basis for the glk1 glk2 phenotype, we further characterized the effects of the mutation on photosynthetic gene expression and on flux through the chlorophyll pathway. Using inducible gene expression combined with transcriptome analysis, we show that GLK genes encode transcriptional activators that promote the expression of a number of genes that are required for chlorophyll biosynthesis and light-harvesting functions. In addition, we provide evidence that GLK1 binds directly to the promoter sequences of many of these genes and use this information to predict a GLK cis-element. Finally, we show that GLK genes regulate the expression of one of these genes independently of the phyB signaling pathway and that GLK genes are sensitive to plastid-derived retrograde signals. Together, these findings demonstrate that GLK proteins help coordinate the transcription of a suite of photosynthetic genes and suggest that GLK function may optimize photosynthetic capacity by integrating responses to variable environmental and endogenous cues.

RESULTS

Constitutive Expression of GLK1 and GLK2 Stimulates Expression of Light Harvesting and Chlorophyll Biosynthesis Genes

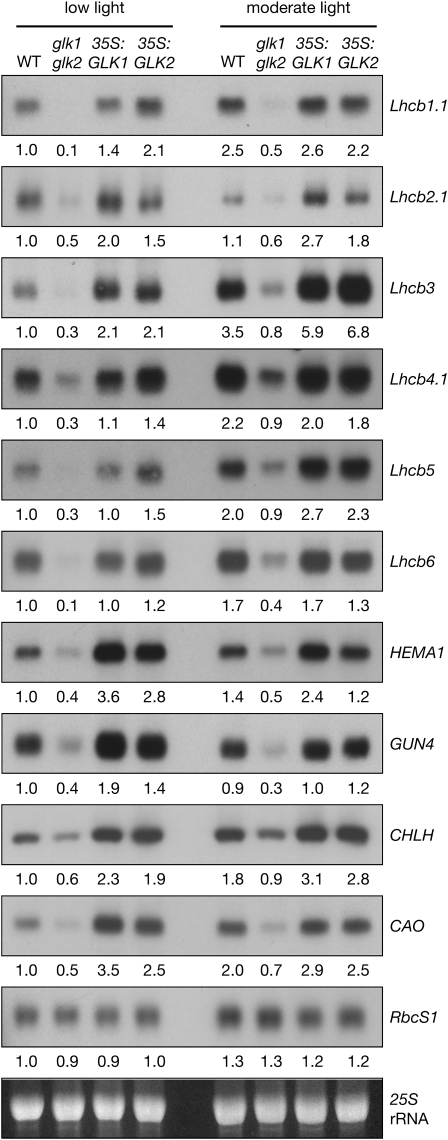

Several genes encoding proteins associated with light harvesting and chlorophyll biosynthesis are downregulated in glk1 glk2 mutants (Fitter et al., 2002; Yasumura et al., 2005). To determine whether this defect can be rescued by constitutive expression of GLK1 or GLK2, transcript levels were compared in wild-type, double mutant, and overexpressing plants. With respect to light harvesting, steady state transcript levels for Lhcb1-6 are reduced in glk1 glk2 mutants, to ∼10 to 50% of the wild type (Figure 1). Overexpression of GLK genes fully complements this defect and notably leads to transcript levels of Lhcb2.1 and Lhcb3 that are approximately twofold higher than the wild type. This relationship is true for plants grown under two different light intensities. Importantly, both glk1 glk2 mutants and GLK overexpressors adapt to light intensity in a similar manner to the wild type; that is, Lhcb transcript levels increase with the availability of light, at least at the relatively low light intensities used in this experiment and elsewhere (Ruckle et al., 2007). Thus, light intensity-dependent regulation of photosynthetic gene expression is unperturbed in glk1 glk2 mutants.

Figure 1.

Overexpression of GLK Genes Leads to Enhanced Transcript Levels of Nuclear Photosynthetic Genes.

RNA gel blot analysis showing transcript levels in wild-type, double mutant (glk1 glk2), and double mutant lines overexpressing either GLK1 (35S:GLK1) or GLK2 (35S:GLK2). Plants were grown for 28 d under 30 or 100 μmol quanta·m−2·s−1 (low light and moderate light, respectively) at 21°C. All tissue samples were harvested within 20 min, starting at 3 h after subjective dawn. Ten micrograms of total RNA was loaded per lane. Blots were exposed to a phosphor-imager screen for quantification; images shown are subsequent exposures to autoradiography film. Values below each blot denote the approximate fold-change relative to the wild type grown under low light, standardized to 25S rRNA on the ethidium bromide–stained gel.

To examine the relationship between GLK function and chlorophyll biosynthesis, the expression profiles of four genes regulating key enzymatic steps (Larkin et al., 2003; Tanaka and Tanaka, 2007) in the pathway were monitored: HEMA1 (glutamyl-tRNA reductase [GluTR], which catalyzes the rate-limiting and first committed step in tetrapyrrole biosynthesis), CHLH (the H subunit of Mg-chelatase, which diverts tetrapyrroles toward chlorophyll biosynthesis), GUN4 (required for efficient Mg-chelatase activity), and CAO (which catalyzes the conversion of chlorophyllide a to chlorophyllide b). As anticipated, transcript levels of all four genes were substantially reduced in glk1 glk2 mutants (Figure 1). Surprisingly, however, overexpression of GLK genes led to transcript levels that were approximately two- to threefold higher than the wild type, an effect that was most pronounced under low light conditions (Figure 1). Consistent with the increased levels of chlorophyll observed in GLK-overexpressing lines (Waters et al., 2008), this finding implies that GLK genes promote the transcription of genes responsible for key steps in chlorophyll biosynthesis and thus may increase flux through the pathway.

Importantly, the positive effect of GLK overexpression on photosynthetic gene expression is not universal because transcript levels of RbcS1 (nuclear-encoded small subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) do not differ between the four genotypes considered (Figure 1). This is consistent with the earlier report that RbcS transcripts are unaffected in glk1 glk2 mutants (Fitter et al., 2002). This observation suggests that GLK genes primarily influence genes related to light harvesting and chlorophyll biosynthesis.

Flux through the Chlorophyll Pathway Is Compromised in Dark-Grown glk1 glk2 Mutants

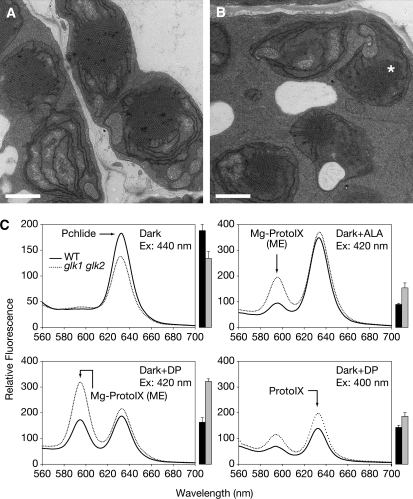

While the glk1 glk2 phenotype is readily observable in light-grown plants, it is not known whether GLK genes are required for chloroplast development in the absence of light. Etiolated seedlings do not synthesize chlorophyll, but instead prepare for eventual light exposure by accumulating large quantities of protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) in developmentally arrested plastids called etioplasts. In the etioplast stroma, the accumulated Pchlide, together with NADPH:Pchlide oxidoreductase, forms a crystalline array called the prolamellar body (Sundqvist and Dahlin, 1997). To establish whether plastids of dark-grown glk1 glk2 mutants are phenotypically distinguishable from those of the wild type, we examined the ultrastructure of cotyledon etioplasts. While still exhibiting a crystalline appearance, the prolamellar bodies of glk1 glk2 etioplasts were smaller than those of the wild type, invariably occupying less of the stroma (Figures 2A and 2B). Wild-type and mutant prolamellar bodies exhibited a mean width of 1.62 ± 0.06 μm and 1.06 ± 0.08 μm, respectively, when measured at the widest point (n = 12). This observation implies that glk1 glk2 mutants accumulate lower levels of chlorophyll precursors, even in the dark.

Figure 2.

Dark-Grown glk1 glk2 Seedlings Exhibit Defects in the Chlorophyll Biosynthetic Pathway.

(A) and (B) Transmission electron micrographs of etioplasts in the cotyledons of dark-grown 4-d-old wild type (A) and glk1 glk2 seedlings (B). Asterisk denotes the prolamellar body. Bars = 1 μm.

(C) Levels of chlorophyll intermediates in dark-grown wild-type and glk1 glk2 seedlings as determined by spectrofluorometry. Top left panel: untreated seedlings. Excitation at 440 nm produces an emission peak at 632 nm corresponding to Pchlide. Top right panel: seedlings treated with 10 mM ALA. Excitation at 420 nm produces an emission peak at 595 nm corresponding to MgProtoIX (ME) and an additional, nonspecific peak at 632 nm corresponding to Pchlide and protoporphyrin IX (ProtoIX) (Pontier et al., 2007). Bottom panels: seedlings treated with 10 mM DP. In the bottom right panel, excitation at 400 nm produces an emission peak at 632 nm corresponding to ProtoIX. Bars to the right of each chart show quantification of the arrowed peak (mean ± se, n = 3 biological replicates). The wild type is represented with black bars and glk1 glk2 with gray bars.

Consequently, we measured levels of chlorophyll precursors in dark-grown seedlings by spectrofluorometry. Figure 2C shows that levels of Pchlide are reduced in glk1 glk2 mutants, implying that GLK function is required for normal Pchlide synthesis in the dark. This observation, in combination with the reduced accumulation levels of transcripts encoded by chlorophyll biosynthesis genes (Figure 1), suggested that loss of GLK function might reduce flux through the entire pathway. To test this suggestion, we fed dark-grown seedlings with 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), an early tetrapyrrole precursor. Excitation at 420 nm produces an emission peak at 595 nm corresponding to Mg-Protoporphyrin IX (Mg-ProtoIX) and/or Mg-Protoporphyrin IX methyl ester (Mg-ProtoIX ME) (Pontier et al., 2007). Notably, feeding with ALA increased the 595-nm peak in glk1 glk2 relative to the wild type (Figure 2C), implying reduced activity of Mg-ProtoIX methyltransferase and/or Mg-ProtoIX ME cyclase in the mutant. In addition, excitation at 440 nm produced a 632-nm emission peak, contributed mainly by Pchlide, that was almost equalized between glk1 glk2 and the wild type upon feeding with ALA (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). This result suggests that decreased ALA synthesis might be also responsible for the decreased Pchlide levels in the mutant.

We further fed dark-grown seedlings with 2,2′-dipyridyl (DP). DP inhibits the conversion of ProtoIX to heme and also the conversion of Mg-ProtoIX to Pchlide, thus leading to the accumulation of Mg-ProtoIX and Mg-ProtoIX ME (Mochizuki et al., 2001; see also Figure 4). As expected, feeding with DP led to reduced amounts of Pchlide in both the wild type and glk1 glk2 (see Supplemental Figure 1 online), but it also produced a large increase in Mg-ProtoIX and/or Mg-ProtoIX ME levels in the mutant relative to the wild type (Figure 2C). Since DP inhibition is presumed to occur immediately after Mg-ProtoIX ME, the different increases in the 595-nm peak suggest that at least Mg-ProtoIX was accumulating in the mutant. Moreover, excitation at 400 nm (which is specific for ProtoIX) led to a higher emission peak at 632 nm in the mutant than in the wild type (Figure 2C) that was not seen when excitation was performed at 440 nm (see Supplemental Figure 1 online).

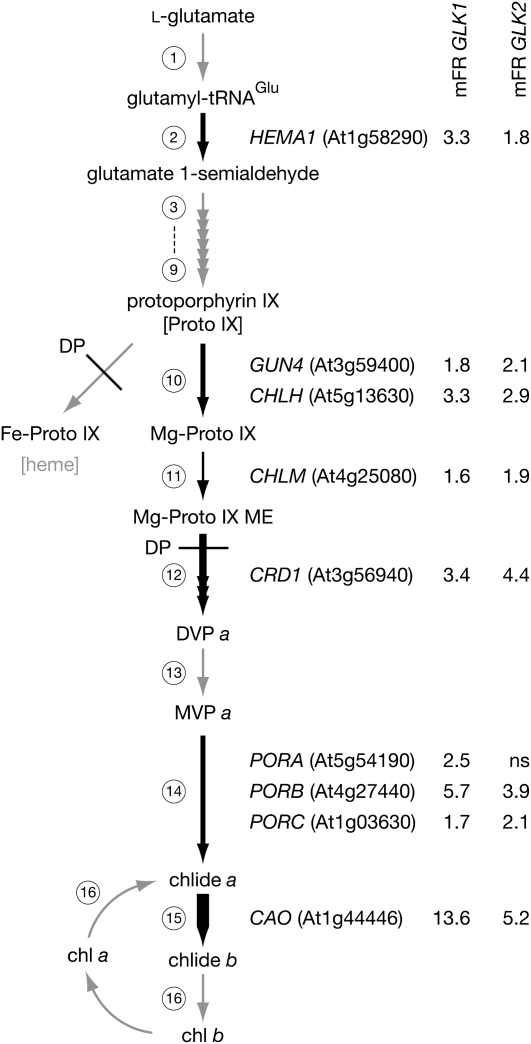

Figure 4.

Effect of GLK1 and GLK2 Induction on the Chlorophyll Biosynthetic Pathway.

Schematic of the chlorophyll biosynthetic pathway with steps with significant changes in gene transcript levels following GLK induction depicted with black arrows; the relative strength of induction is reflected in the thickness of the arrow. Nonsignificantly changed steps and pathways are depicted with gray arrows. Values represent the mean fold ratio (mFR) change in gene expression (induced relative to noninduced) following induction of GLK1 and GLK2. For clarity, only genes with significantly changed transcript levels are shown for each step. Significance threshold of P ≤ 0.05, n ≥ 3 biological replicates. ns, not significant. Circled numbers refer to enzymatic steps listed in Supplemental Table 6 online, which details the changes in all genes involved in this pathway. Steps inhibited by DP are also shown. The genes are HEMA1; GUN4; CHLH; CHLM, Mg-protoporphyrin IX methyl transferase; CRD1, Mg-protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester cyclase; PORA/PORB/PORC, protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase A/B/C; CAO; MgProtoME, magnesium protoporphyrin monomethyl ester; DVP, divinylprotochlorophyllide; and MVP, monovinylprotochlorophyllide.

This suggests that ProtoIX also accumulates to higher levels in the mutant than the wild type when treated with DP. The elevated accumulation of ProtoIX and Mg-ProtoIX is consistent with the reduced levels of GUN4 and CHLH transcripts and those of CHLM (encoding Mg-ProtoIX methyltransferase), as implied by the transcriptome analysis below. Additionally, decreased levels of heme and/or Pchlide in mutant seedlings may depress negative feedback of GluTR, either directly or via FLU, a negative regulator of chlorophyll biosynthesis (Terry and Kendrick, 1999; Meskauskiene et al., 2001; Goslings et al., 2004). This effect would further enhance levels of ProtoIX and Mg-ProtoIX relative to the wild type when treated with DP. Together, these findings indicate a general reduction of flux through the chlorophyll pathway in glk1 glk2 mutants and imply that glk1 glk2 mutants process ProtoIX and Mg-ProtoIX at a slower rate than the wild type.

Induction of GLK1 and GLK2 Leads to Increased Levels of Chlorophyll

To gain insight into the targets of GLK transcription factors, we designed an experiment where expression of GLK1 or GLK2 could be induced in a glk1 glk2 mutant background. The aim was to measure transcriptome changes following induction. A two-component glucocorticoid-inducible system was used to drive GLK1 or GLK2 expression following treatment with dexamethasone (DEX) (Craft et al., 2005). Briefly, the GLK1 and GLK2 coding sequences were cloned behind a chimeric promoter consisting of a minimal cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and six ideal lac operator sequences, termed pOp6 (Kannangara et al., 2007). These constructs were then independently transformed into a transgenic glk1 glk2 line carrying a transcriptional activator LhGR-N driven by a constitutively active 35S promoter. Application of DEX facilitates entry of LhGR-N into the nucleus and consequent activation of transcription from the pOp6 promoter. This method requires subsequent translation of GLK mRNA and therefore precludes the inhibition of protein synthesis when monitoring for downstream transcriptional changes.

The progeny of primary transformants carrying pOp6:GLK1 or pOp6:GLK2 were first screened for their capacity to induce GLK expression following application of DEX. DEX (10 μM) was sufficient to induce a strong transcriptional response when plants were grown on media containing the hormone, and induced plants contained significantly more chlorophyll than uninduced siblings (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). However, chlorophyll levels were still substantially lower than the wild type, implying that induced expression was insufficient to fully rescue the mutant phenotype. Although both inducible constructs encoded a C-terminal FLAG epitope tag, we were unable to detect GLK1 or GLK2 proteins following induction, consistent with the reported protein instability (Waters et al., 2008).

To confirm that GLK-FLAG fusion proteins are indeed functional, identical coding sequences were expressed from the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter. Significantly, these constructs fully complemented the glk1 glk2 mutant phenotype (see Supplemental Figure 3 online). The incomplete phenotypic rescue by pOp6:GLK1/GLK2 is unlikely to be caused by low transcript abundance, as levels were substantially higher than the wild type (see Supplemental Figure 4 online). Instead, it may reflect a developmental window when GLK expression is fundamentally required and/or a location that may not be accessible to DEX, such as young leaf primordia. Because at least partial complementation was possible, the most strongly induced transgenic line for each of pOp6:GLK1 and pOp6:GLK2 (line T23 for both; see Supplemental Figure 2 online) was selected for subsequent microarray experiments.

To determine the optimal time for induction, GLK1 and GLK2 transcript levels were measured over time after DEX application. Seedlings were germinated on agar plates and 10 d later were transferred to liquid medium and allowed to recover for 48 h. Induction was achieved by adding 10 μM DEX. GLK1 and GLK2 transcripts were detectable within 1 h of induction and reached a maximum within 4 to 8 h (see Supplemental Figure 4 online). On the basis of these kinetics, we reasoned that a 4-h induction period would allow sufficient time for GLK accumulation (both RNA and protein) and activation of direct targets, while minimizing secondary indirect effects associated with longer induction periods.

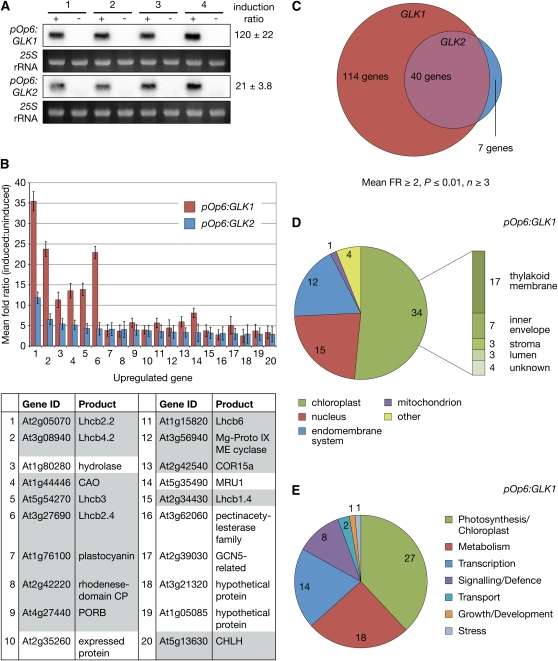

GLK1 and GLK2 Upregulate Similar Genes

To analyze the genome-wide effects on transcription following GLK induction, microarray experiments were performed on four independent biological replicates for each of pOp6:GLK1 and pOp6:GLK2. Following RNA extraction, we confirmed induction of GLK1 or GLK2 transcripts in each sample by RNA gel blot analysis. Within each line, all four replicates showed strong and consistent induction, although pOp6:GLK1 induced approximately sixfold more strongly than pOp6:GLK2 (Figure 3A). Strikingly, microarray analysis revealed that GLK1 and GLK2 upregulate very similar sets of genes (Figures 3B and 3C). Responsive genes were identified using a stringent significance threshold: a mean fold change ≥2 (induced relative to uninduced samples) and a P value ≤0.01, based on at least three out the four replicates.

Figure 3.

Induction of GLK Expression Promotes Transcription of Photosynthesis-Related Genes.

(A) RNA gel blot showing GLK1 and GLK2 transcript accumulation following induction. Four independent biological replicates (1 to 4) of seedlings carrying pOp6:GLK1 or pOp6:GLK2 transgenes were grown under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle, induced 6 h after dawn with 10 μM DEX (+) or mock-treated with 0.1% DMSO (−), and then harvested 4 h later. Five micrograms of total RNA was loaded in each lane, and hybridization was quantified using a phosphor-imager. The induction ratio is calculated as (induced value)/(mock value) and expressed as a mean ± se (n = 4).

(B) The mean fold ratio for the 20 most upregulated genes following GLK2 induction (blue) is plotted alongside the mean fold ratio for the same genes following GLK1 induction (red). Note that the GLK1-induced genes are generally more strongly affected than GLK2-induced genes. Error bars are sd (n ≥ 3 biological replicates). The table lists the 20 genes depicted in the chart; shaded cells correspond to photosynthetic/chloroplast-localized gene products and are described in the text. Supplemental Table 2 online lists all genes significantly changed in response to GLK2 induction and therefore lists the details of these top 20 genes.

(C) The number of upregulated genes shared between induced pOp6:GLK1 and pOp6:GLK2 samples are represented by overlapping circles, the areas of which are proportional to the number of genes that pass the significance threshold.

(D) Subcellular and subchloroplastic localization of gene products induced by GLK1. Gene products were assigned a location based on GO annotation. If unknown, the location was predicted by WoLF PSORT and assigned a location if this prediction was unambiguous. Unknown or ambiguous locations were excluded. GO annotations and assigned locations are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online.

(E) Functional characterization of gene products induced by GLK1. Gene products were assigned a function based on GO annotation. GO annotations and assigned functions are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online.

When ranked by mean fold change, the 20 most affected genes following GLK2 induction were also significantly induced by GLK1; most prominent in this list were Lhcb and chlorophyll biosynthesis genes (Figure 3B). These 20 genes tended to show a stronger response in pOp6:GLK1 samples than pOp6:GLK2 samples, likely reflecting the difference in induction strength in these two lines (Figure 3A). Consistent with this inference, 114 genes satisfied the significance threshold and were upregulated in response to GLK1, compared with 47 for GLK2. Of these 47 genes, 40 were also upregulated by GLK1 (Figure 3C), and of the seven excluded genes, five were omitted from the GLK1 list based solely on a fold ratio marginally <2 (see Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 online).

When the data sets of GLK1 and GLK2 are combined, the similarity in upregulated genes becomes most evident and the changes are highly statistically significant (Table 1; see Supplemental Table 3 online). By contrast, only 10 and three genes were downregulated by GLK1 and GLK2, respectively, using the same significance threshold (see Supplemental Tables 4 and 5 online). Furthermore, none of these genes was consistently downregulated by both GLK1 and GLK2. Together, these data suggest that GLK1 and GLK2 promote the expression of highly similar genes, consistent with their known functional equivalency.

Table 1.

Twenty Most Upregulated Genes following Induction of GLK1 and GLK2

| Gene ID | Name | Locationa | GLK1 mFRb | GLK1 P Value | nc | GLK2 mFRb | GLK2 P Value | nc | Comb. mFRd | Comb. P Value | nc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At2g05070 | Lhcb2.2 | Thy. | 35.5 | 3.71E-08 | 3 | 11.8 | 2.79E-08 | 4 | 19.0 | 1.50E-09 | 7 |

| At3g08940 | Lhcb4.2 | Thy. | 23.8 | 5.71E-09 | 4 | 6.5 | 5.93E-07 | 4 | 12.5 | 2.03E-09 | 8 |

| At3g27690 | Lhcb2.4 | Thy. | 22.9 | 4.52E-10 | 4 | 4.2 | 7.26E-06 | 4 | 9.9 | 7.85E-08 | 8 |

| At1g80280 | Hydrolase, α-β | PM? | 11.3 | 6.02E-08 | 4 | 5.4 | 3.67E-07 | 4 | 7.9 | 1.83E-09 | 8 |

| At1g44446 | CAO | IE | 13.6 | 8.57E-08 | 3 | 5.2 | 5.51E-07 | 4 | 7.9 | 6.95E-09 | 7 |

| At5g54270 | Lhcb3 | Thy. | 13.9 | 1.70E-09 | 4 | 4.3 | 9.97E-07 | 4 | 7.8 | 2.37E-08 | 8 |

| At5g35490 | MRU1 (unknown) | Mit.? | 8.1 | 7.36E-08 | 4 | 3.3 | 3.87E-03 | 3 | 5.5 | 1.14E-06 | 7 |

| At5g48490 | LTP (unknown lipid transfer protein) | endo.? | 8.6 | 3.88E-09 | 4 | 2.7 | 1.16E-04 | 4 | 4.8 | 5.07E-07 | 8 |

| At4g27440 | Protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (PORB) | IE | 5.7 | 5.39E-10 | 4 | 3.9 | 1.33E-04 | 4 | 4.8 | 4.45E-10 | 8 |

| At1g15820 | Lhcb6 | Thy. | 5.7 | 1.61E-06 | 4 | 3.6 | 2.20E-04 | 4 | 4.5 | 1.02E-07 | 8 |

| At2g42540 | COR15a | Str. | 5.9 | 1.22E-05 | 3 | 3.3 | 1.57E-04 | 4 | 4.3 | 1.70E-07 | 7 |

| At1g76100 | Plastocyanin | Lum. | 3.8 | 2.41E-06 | 4 | 4.1 | 2.71E-05 | 4 | 4.0 | 1.24E-08 | 8 |

| At2g39030 | GNAT family | ? | 5.1 | 1.88E-05 | 4 | 3.0 | 2.13E-04 | 4 | 3.9 | 7.86E-07 | 8 |

| At3g56940 | Mg-proto IX ME cyclase (CRD1) | IE | 4.4 | 3.44E-05 | 4 | 3.4 | 3.03E-04 | 4 | 3.9 | 1.40E-06 | 8 |

| At2g42220 | Rhodanese-like domain | Thy. | 3.7 | 3.26E-06 | 4 | 4.1 | 7.83E-05 | 4 | 3.9 | 1.64E-07 | 8 |

| At2g35260 | Expressed protein | ? | 4.0 | 2.25E-06 | 4 | 3.7 | 2.43E-04 | 4 | 3.9 | 6.58E-09 | 8 |

| At2g34430 | Lhcb1.4 | Thy. | 3.8 | 3.06E-05 | 4 | 3.2 | 6.34E-05 | 4 | 3.5 | 2.63E-08 | 8 |

| At4g05180 | PsbQ2 | Thy. | 4.6 | 3.24E-06 | 4 | 2.6 | 1.11E-04 | 4 | 3.5 | 3.45E-08 | 8 |

| At1g68190 | Zinc finger family | Nuc. | 4.3 | 7.08E-06 | 4 | 2.7 | 3.15E-04 | 4 | 3.4 | 1.84E-06 | 8 |

| At1g05085 | Hypothetical protein | ? | 3.7 | 9.19E-04 | 3 | 2.9 | 8.64E-04 | 4 | 3.2 | 8.97E-06 | 7 |

Ranked by combined fold ratio across both GLK1 and GLK2 data sets.

Thy., thylakoid membrane; lum., thylakoid lumen; IE, chloroplast inner envelope; str, chloroplast stroma; mit., mitochondrion; endo., endomembrane system; nuc., nucleus; ?, unknown/uncertain.

Mean fold ratio of signal (induced:mock-treated).

Number of independent observations (arrays scored).

Combined fold ratio across both GLK1 and GLK2 data sets.

GLK-Regulated Genes Are Primarily Involved in Photosynthetic Function

Genes significantly upregulated by GLK1 were categorized according to the predicted or known subcellular location of their gene products. Of 114 proteins, 66 could be unambiguously localized to a cellular compartment based on annotation or computational prediction using WoLF PSORT (Horton et al., 2007). Approximately half of these proteins were localized to the chloroplast, a further half of which were thylakoid proteins (Figure 3D). When classified according to known or predicted molecular function, 27 of 71 genes were involved in photosynthesis or chloroplast function, with a further 18 and 14 involved in general metabolism and transcription, respectively (Figure 3E).

To assess the degree to which these classifications are overrepresentative of Arabidopsis proteins as a whole, the GLK1-upregulated genes were submitted to enrichment analysis using the DAVID Functional Annotation tool (Huang et al., 2007). When classified according to Gene Ontology (GO) terms relating to biological process, cellular compartment, and molecular function, photosynthesis-related terms are by far the most highly represented and are highly significantly enriched (Table 2). The three most enriched biological processes (protein-chromophore linkage, photosynthesis, light harvesting, and chlorophyll biosynthetic process) imply that GLK genes promote the expression of nuclear genes relating both to Lhcb assembly and chlorophyll biosynthesis.

Table 2.

Functional Enrichment of GLK1-Induced Genes

| Term ID | Term | Counta | %b | FEc | P Valuede |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO: Biological Process (BP) | |||||

| GO:0015979 | Photosynthesis | 15 | 13.51 | 25.47 | 4.29E-16 |

| GO:0009765 | Photosynthesis, light harvesting | 10 | 9.01 | 58.35 | 7.26E-14 |

| GO:0018298 | Protein-chromophore linkage | 5 | 4.50 | 61.72 | 1.13E-06 |

| GO:0006091 | Generation of precursor metabolites and energy | 17 | 15.32 | 3.99 | 2.32E-06 |

| GO:0015995 | Chlorophyll biosynthetic process | 5 | 4.50 | 44.58 | 4.36E-06 |

| GO:0015994 | Chlorophyll metabolic process | 5 | 4.50 | 35.66 | 1.08E-05 |

| GO:0046148 | Pigment biosynthetic process | 6 | 5.41 | 20.06 | 1.13E-05 |

| GO:0033014 | Tetrapyrrole biosynthetic process | 5 | 4.50 | 23.60 | 5.61E-05 |

| GO: Cellular Compartment (CC) | |||||

| GO:0009579 | Thylakoid | 22 | 19.82 | 14.34 | 7.51E-19 |

| GO:0044434 | Chloroplast part | 19 | 17.12 | 11.26 | 2.79E-14 |

| GO:0031984 | Organelle subcompartment | 16 | 14.41 | 14.17 | 2.23E-13 |

| GO:0042651 | Thylakoid membrane | 15 | 13.51 | 16.07 | 2.93E-13 |

| GO:0009507 | Chloroplast | 33 | 29.73 | 3.59 | 1.44E-11 |

| GO:0009522 | PSI | 6 | 5.41 | 52.14 | 8.46E-08 |

| GO:0009523 | PSII | 7 | 6.31 | 24.51 | 3.58E-07 |

| GO:0031090 | Organelle membrane | 16 | 14.41 | 4.95 | 4.33E-07 |

| GO:0043231 | Intracellular membrane-bound organelle | 46 | 41.44 | 1.46 | 5.38E-04 |

| GO: Molecular Function (MF) | |||||

| GO:0016168 | Chlorophyll binding | 4 | 3.60 | 131.50 | 3.19E-06 |

| GO:0000287 | Magnesium ion binding | 6 | 5.41 | 8.77 | 5.66E-04 |

| GO:0016628 | Oxidoreductase activity | 3 | 2.70 | 42.27 | 2.22E-03 |

| GO:0030528 | Transcription regulator activity | 13 | 11.71 | 2.66 | 2.56E-03 |

| GO:0046906 | Tetrapyrrole binding | 6 | 5.41 | 5.80 | 3.48E-03 |

| GO:0003700 | Transcription factor activity | 11 | 9.91 | 2.81 | 4.57E-03 |

| GO:0016630 | Protochlorophyllide reductase activity | 2 | 1.80 | 197.25 | 9.94E-03 |

A total of 114 genes were submitted to the DAVID Functional Enrichment Chart tool, resulting in 111 unique gene IDs. Terms are ranked by significance of overrepresentation.

Number of submitted genes with GO term.

Proportion of submitted genes with GO term.

Relative fold enrichment (FE) of GO term compared with Arabidopsis gene background.

Significance of fold enrichment (FE), given by a modified Fisher Exact test (Hosack et al., 2003).

Terms were included in list if P < 0.001 for BP and CC, or P < 0.01 for MF.

Besides genes known to be directly involved in photosynthesis, several upregulated genes were identified whose products are either targeted to the chloroplast or involved in chloroplast regulatory processes. These include two related cold-responsive proteins targeted to the chloroplast stroma (COR15a and b), two rhodanese-like domain-containing proteins targeted to the thylakoid lumen, and CIA2, a nuclear transcription factor involved in the expression of two components of the plastid protein import complex (Sun et al., 2001). In addition, a nuclear-encoded chloroplast RNA polymerase σ-subunit was upregulated by both GLK1 and GLK2. This protein is required for the expression of chloroplast-encoded photosynthetic proteins and tRNAs, including tRNAGlu, an early intermediate in the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis pathway (Hanaoka et al., 2003). Interestingly, phytoene synthase was also significantly upregulated, which is consistent with the need for carotenoid biosynthesis during LHC assembly.

Key Steps of the Chlorophyll Pathway Are Upregulated following GLK Induction

Given that chlorophyll biosynthesis is clearly perturbed in glk1 glk2 double mutants, we identified genes corresponding to each step in tetrapyrrole and chlorophyll biosynthesis and assessed how transcript levels changed in response to GLK1 and GLK2 induction. This approach revealed five key steps that are influenced by GLK1 and GLK2 induction (Figure 4; see Supplemental Table 6 online). The tetrapyrrole pathway starts with the generation of glutamate 1-semialdehyde and branches at ProtoIX. At this point, ProtoIX is diverted toward either chlorophyll or heme biosynthesis by the chelation of Mg2+ or Fe2+, respectively. As expected, HEMA1 was significantly upregulated, but no other steps prior to Proto IX were affected. The branch toward chlorophyll, catalyzed by Mg-cheletase, was strongly promoted: both CHLH and GUN4 registered significant increases (Figure 4). Interestingly, expression of the two other subunits of Mg-cheletase, CHLD and CHLI, was unchanged, a finding consistent with other work, indicating that transcriptional regulation of this step is achieved through CHLH and GUN4 (Matsumoto et al., 2004; Stephenson and Terry, 2008).

Most notably, genes encoding Fe-cheletase and downstream heme biosynthetic enzymes were unaffected, suggesting a specific upregulation of the chlorophyll branch of the pathway. Thereafter, three major steps were upregulated by GLK induction: (1) the generation of divinylprotochlorophyllide a, a three-step reaction that requires Mg-ProtoIX monomethylester cyclase (CRD1); (2) the generation of chlorophyllide a by Pchlide oxidoreductase (PORA, PORB, and PORC); and (3) the oxidation of chlorophyllide a to chlorophyllide b by CAO. The upregulation of CRD1 is consistent with the observation that mutant plants accumulate Mg-ProtoIX following addition of ALA (Figure 2), indicative of a block in CHLM or CRD1 activity. The particularly pronounced upregulation of CAO transcript levels, with an average of 7.9-fold increase following GLK induction (Figure 4, Table 1), is similarly consistent with the link between chlorophyll b and Lhcb stability, and the substantially induced expression of Lhcb genes by GLK1 and GLK2.

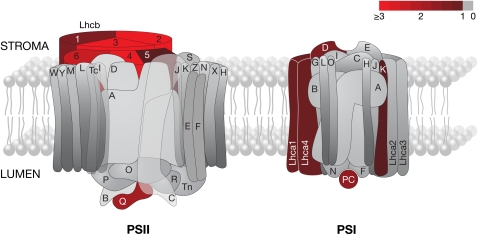

Light-Harvesting Antenna Proteins Are Significantly Upregulated by GLK1

Five of the 10 most upregulated genes following GLK1 and GLK2 induction encode subunits of LHCII (Table 1). Considering that GLK1 induction yielded the most dramatic transcriptional changes, we examined the response of all nuclear genes encoding subunits of PSII, PSI, and the associated antennae, LHCII and LHCI (Figure 5; see Supplemental Table 7 online). In Arabidopsis, 10 individual genes in three classes (Lhcb1.x, Lhcb2.x, and Lhcb3) encode the trimeric LHCII, and a total of five genes in three classes (Lhcb4.x, Lhcb5, and Lhcb6) encode the peripheral minor antenna proteins. As anticipated, at least one gene family member corresponding to each of the six subunits of the light-harvesting antenna of PSII was significantly upregulated, some of them dramatically so. Intriguingly, not all gene members within the same class responded equivalently: while Lhcb4.2 increased 24-fold, Lhcb4.1 only increased 1.8-fold, whereas Lhcb4.3 showed no significant change (see Supplemental Table 7 online). An extensive metastudy of Lhc transcript profiles revealed subtly different patterns of expression between Lhc family members; notably, Lhcb2.1 and Lhcb2.2 share a similar tissue-specific expression profile distinct from Lhcb2.3, and Lhcb4.3 is weakly expressed relative to Lhcb4.1 and Lhcb4.2 except in pedicels (Klimmek et al., 2006). The functional basis for this distinction in not obvious, but these differences are consistent with the responses to GLK genes described here.

Figure 5.

Thylakoid-Associated Photosynthetic Components Significantly Upregulated following Induction of GLK1.

Pictorial representation of PSI and PSII. The color scale depicts fold ratio in log2 units; a log2 fold ratio of 1 is equivalent to an absolute fold change of 2. Subunits showing a robust increase (>1) in corresponding transcript levels are highlighted in shades of red, with unchanged subunits in gray (<1). The significance threshold was P ≤ 0.01 (n ≥ 3). Note that only transcripts for nuclear-encoded proteins could be detected on the microarrays used. Subunits of PSI and PSII are referred to as Psa§ and Psb§, respectively, where § corresponds to the lettered labels in the figure. PC, plastocyanin. Gene IDs, significance levels, and mean fold ratios in absolute units for each subunit are listed in Supplemental Table 7 online. Figure redrawn with permission from J. Nield following the scheme at http://photosynthesis.sbcs.qmul.ac.uk/nield/psIIimages/oxygenicphotosynthmodel.html (accessed September 2, 2008).

Expression of the six Lhca genes encoding the PSI antenna was more moderately stimulated by GLK1: only two subunits surpassed the significance threshold, and expression levels increased less than threefold. Only one nuclear-encoded subunit of the PSII core complex responded robustly to GLK1 induction: PsbQ-2. PsbQ is an extrinsic protein that forms part of the oxygen-evolving complex and is necessary for PSII stability under light-limiting conditions (Yi et al., 2006). Likewise, changes in core complex subunits of PSI were relatively weak with PsaD and PsaK upregulated two- to threefold. Beyond sustaining PSI function, the role of PsaD is unclear (Haldrup et al., 2003); however, PsaK appears to interact with LHCI and may stabilize the association of LHCI with the PSI core complex (Jensen et al., 2000). The lumenal electron carrier plastocyanin was also stimulated by GLK1 expression, perhaps reflecting the increased electron flow associated with enhanced light interception by LHC antennae.

Induction of GLK Expression Leads to Sustained Increases in Photosynthetic Gene Expression

To verify the microarray results, we assessed the accumulation of transcripts corresponding to several photosynthetic genes over a 24-h period following GLK1 and GLK2 induction (Figure 6). In general, transcripts responded more strongly to GLK1 than GLK2, as suggested by the microarray data and the GLK1 and GLK2 induction profiles (Figures 3 and 6). Unambiguous evidence of increased transcript levels was visible 4 h after induction, with some genes showing increases after just 2 h (e.g., GUN4 and CAO). In agreement with the microarray data, the most dramatically affected transcripts were those for Lhcb1.1 and Lhcb6. While transcript levels in induced samples tended to peak at 4 to 8 h, concomitant with GLK transcript levels, levels remained elevated relative to the uninduced controls after 24 h. Importantly, transcripts for RbcS1 remained stable throughout the 24-h time course. On the basis of these data, we conclude that the GLK-induced changes observed by microarray analysis are valid.

Figure 6.

Accumulation of Photosynthesis-Related Transcripts following GLK Induction.

RNA gel blot analysis following GLK induction. Replicate sets of seedlings carrying either pOp6:GLK1 or pOp6:GLK2 were simultaneously treated with 10 μM DEX (+) or mock-treated with 0.1% DMSO (−) and harvested at the times shown. Seedlings were grown under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle, and induction was performed 6 h after dawn. glk1 glk2 seedlings carrying the LhGR-N transgene were used as negative controls and harvested either immediately after addition of DEX (+0) or 24 h afterwards (+24). Ten micrograms of total RNA was loaded per lane, and replicate blots were probed and quantified using a phosphor imager. Values below each blot represent the fold ratio calculated as (induced value)/(mock value), after standardization to 25S rRNA on the ethidium bromide–stained gel.

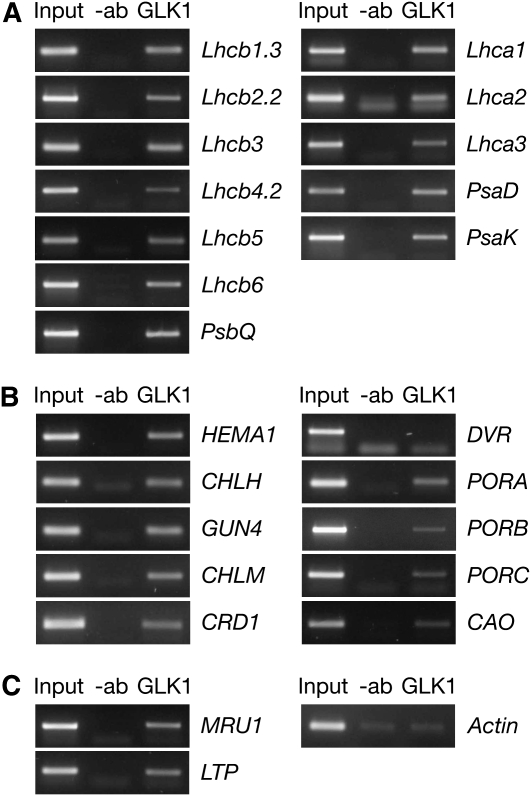

GLK Proteins Bind to Promoters of Several Photosynthetic Genes

To assess whether the upregulated genes identified by the microarray analysis are directly influenced by GLK activation, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed with nuclear extracts from 35S:GLK1 plants and antibodies raised against GLK1. PCR amplification revealed that the population of immunoprecipitated DNA contained promoter sequences of the genes that were most significantly upregulated in the transcriptome analysis (Figure 7). Notably, promoters of all six classes of the Lhcb gene family, several chlorophyll biosynthesis genes, and two genes of unknown function were confirmed as interacting with GLK1. However, no reliable interaction could be confirmed for COR15a, even though it was strongly induced, which may suggest this gene is not a direct GLK1 target. Importantly, no enrichment for promoter sequences corresponding to two uninduced genes (DVR [divinyl Pchlide reductase] and actin) could be detected using this method. These data are consistent with GLK1 acting as a positive transcriptional regulator of several functionally related genes through direct binding to promoter sequences. It is noteworthy that constitutive overexpression of individual photosynthetic genes (HEMA1, CAO, Lhcb1, and Lhcb6) that are otherwise downregulated in glk1 glk2 mutants has no discernible effect on the mutant phenotype (see Supplemental Figure 5 online). This further implies that the glk1 glk2 mutant phenotype is due to multiple defects in photosynthetic development.

Figure 7.

GLK Proteins Bind the Promoter Sequences of Nuclear Photosynthetic Genes.

PCR amplification of promoter sequences following ChIP assays. PSII and PSI genes (A), chlorophyll biosynthesis genes (B), and an actin negative control and two genes of unknown function, MRU1 (At5g35490) and LTP (At5g48490) (C). Sheared chromatin was subjected to immunoprecipitation with GLK1 antibody (+ab) or mock precipitated without antibody (−ab). Genomic DNA was used as a positive control (Input). Association of GLK1 with the promoter of a given gene is determined by enrichment of the PCR product in +ab compared with −ab lanes.

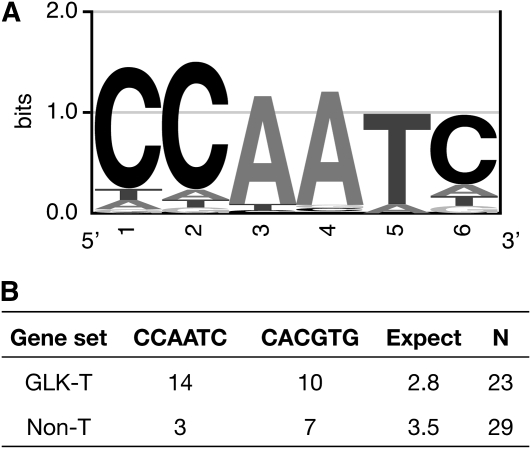

Promoter Analysis of ChIP Targets Reveals a Putative GLK cis-Element

To examine whether the promoters of GLK-regulated genes share a common cis-element, we analyzed the 23 ChIP-positive genes using Weeder, a program that uses a consensus-based method to search for conserved motifs in submitted sequences (Pavesi et al., 2004; Tompa et al., 2005). The evaluation of any motif assesses the frequency and conservation found among the submitted sequences and compares those values to those expected given the nucleotide distributions in upstream sequences of Arabidopsis genes. Submitting 500 bases of sequence upstream of the annotated transcriptional start site of the 23 genes yielded a 6-bp motif, CCAATC, that was widely distributed, well conserved, and significantly overrepresented (Weeder Score 1.13; P < 0.001; Figure 8). While most instances of the motif contained one substitution, eight of the promoters contained one perfect instance, and three promoters contained two (Figure 8; see Supplemental Table 9 online). In addition, the G-box element (CACGTG), a ubiquitous element found in functionally diverse genes (Menkens et al., 1995), was significantly overrepresented (Weeder score of 0.99; P < 0.001) but was less common than CCAATC (Figure 8B). A high-scoring eight-base motif was also discovered (GCCACGTG), but this is essentially an extended G-box.

Figure 8.

A Putative Promoter Binding Element of GLK Transcription Factors.

(A) The first 500 bases upstream of the annotated transcriptional start site of 23 genes identified as positive by ChIP (Figure 7) were analyzed for potential consensus cis-elements using Weeder. The highest scoring six-base motif was CCAATC. All of the occurrences of CCAATC with one or fewer substitutions were used to generate a logo of the consensus sequence. The size of the letter at each position is scaled relative to the information content (a measure of conservation), reflecting the frequency of the corresponding base at each position. This logo is energy normalized using relative entropy to compensate for the low GC content in Arabidopsis.

(B) The upstream 500 bases of the 23 GLK targets (GLK-T) and of 29 photosynthesis-related non-GLK targets (Non-T) were searched for the presence of the CCAATC and CACGTG motifs. The total number of perfect occurrences of each motif over all sequences is given in the table. “Expect” gives the number of expected occurrences of any 6-bp motif over the total sequence length considered, given an equiprobable distribution of nucleotides. Gene lists and a breakdown of element frequencies is provided in Supplemental Table 9 online.

To verify that the CCAATC motif is overrepresented in GLK targets specifically, we examined the promoters of 29 photosynthetic genes that are not GLK targets. These included genes encoding Calvin cycle enzymes as well as chlorophyll biosynthesis genes and PSII subunit genes that were unchanged in the transcriptome analysis (see Supplemental Table 9 online). On the basic assumption that any given six-base motif will occur once every 46 (4096) bases, we observed that CCAATC arose in the non-GLK target promoters no more often than would be expected by chance (Figure 8B). The G-box, meanwhile, occurred more frequently than expected by chance and was more common than CCAATC. Furthermore, CCAATC was not identified as a potential motif by Weeder in these non-GLK targets. Therefore, we tentatively assign CCAATC as a putative GLK recognition sequence.

Extensive efforts to define experimentally the GLK1 binding site have proved unsuccessful. Screens of a random oligo-based library in a bacterial-1-hybrid system (Meng et al., 2005) revealed that while a GLK1 bait transactivates reporter constructs at a level significantly above background, no strong consensus sequence can be identified in recovered clones (data not shown). Furthermore, gel-shift assays coupled with random binding site selection did not lead to an enrichment of sequences, even after several rounds of selection. We consider these findings to indicate that when acting alone, the GLK1 protein binds DNA in a non-sequence-specific manner. Therefore, we anticipate that GLK proteins act in concert with partners to attain specificity in DNA binding. Importantly, GLK1 and GLK2 have been shown to interact with two G-box binding factors in yeast (Tamai et al., 2002), and of the 23 ChIP-positive genes identified in this study, eight contain a perfect G-box in the first 500 bp upstream of the annotated transcription start site (see Supplemental Table 9 online). Therefore, it is possible that various combinations of transcription factors that recognize distinct cis-elements mediate GLK-dependent regulation of transcription. Such a scenario would provide a mechanism for integrating developmental and environmental signals.

GLK Genes Regulate Lhcb6 Transcription Independently of phyB

Photosynthetic development is influenced by red light-perceiving phytochromes (phy), and phyB mutant seedlings are defective in deetiolation and remain pale green throughout development (Reed et al., 1994). To establish whether phyB is required for GLK-dependent regulation of photosynthesis, we generated a phyB glk1 glk2 triple mutant. Three-week-old triple mutants exhibit a combination of glk1 glk2 and phyB parental phenotypes: morphologically they resemble phyB mutants with elongated petioles and thin leaves, and they contain less chlorophyll than either of the parents (Figures 9A and 9B). This additive effect implies that phyB and GLK signals act separately during photosynthetic development.

Figure 9.

GLK- and phyB-Derived Signals Act Independently upon Lhcb6 Expression.

(A) Three-week-old, glasshouse-grown plants of the following genotypes (left to right): the wild type, glk1 glk2, phyB, and phyB glk1 glk2 (triple).

(B) Total chlorophyll content (light gray) and chlorophyll a/b ratio (dark gray) of genotypes shown in (A). Error bars show mean ± se (n = 10 individual plants).

(C) RNA gel blot analysis showing accumulation of Lhcb6 transcripts in seedlings of genotypes shown in (A). Etiolated seedlings were exposed to continuous white, red, or blue light or maintained in the dark for 16 h. Ten micrograms of total RNA was loaded per lane, and replicate blots were hybridized with Lhcb6 or 18S rRNA 32P-labeled DNA fragments and quantified with a phosphor imager. The chart shows Lhcb6 transcript levels, relative to 18s rRNA and standardized such that the wild type = 1 in each light treatment. Column heights denote the mean value from two experimental replicates, with the error bars showing the maximum and minimum values obtained across both replicates.

To assess this idea further, etiolated seedlings of each genotype were grown for 16 h under continuous white, red, or blue light, and Lhcb6 transcript levels were determined as a marker of photosynthetic gene expression patterns. Under white and blue light treatments, Lhcb6 transcripts were lower in phyB than the wild type, but higher than in glk1 glk2 mutants; notably, the reverse was true for red light (Figure 9C). Significantly, the triple mutant was indistinguishable from glk1 glk2 mutants in white and blue light, but accumulated substantially lower levels of Lhcb6 transcripts in the red light conditions that favor phyB-dependent photomorphogenesis. This result suggests that phyB does not act exclusively upon Lhcb6 via GLK proteins and suggests a degree of independence between the phyB and GLK pathways.

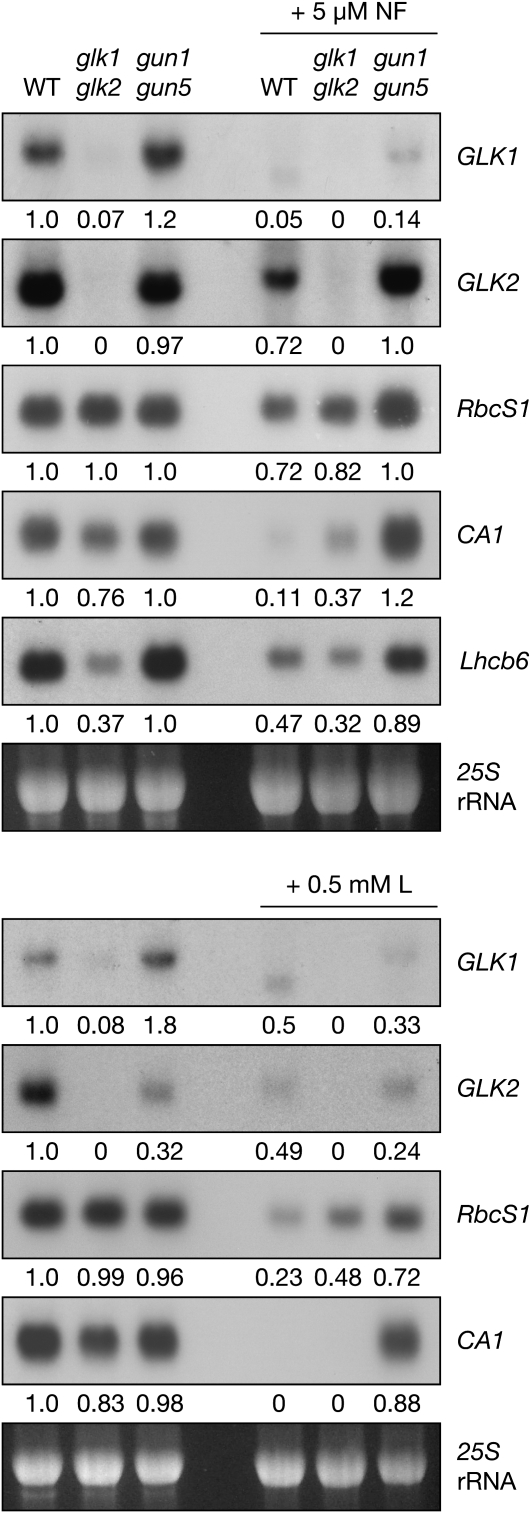

GLK Transcript Levels Are Regulated by Feedback from the Plastid

Many genes encoding photosynthetic proteins are regulated in response to retrograde feedback signals from the plastid. One of these signaling pathways is defined by the genomes uncoupled (gun) mutants, which aberrantly accumulate nuclear photosynthetic gene transcripts in the presence of dysfunctional plastids (Susek et al., 1993). Of the five original gun mutants, four are defective in tetrapyrrole synthesis, implying that perturbations in levels of tetrapyrrole intermediates are generally linked with the GUN repressive signal from the plastid (Strand et al., 2003). The signal molecule itself is not a tetrapyrrole but may be a reactive oxygen species resulting from free phototoxic tetrapyrroles (Mochizuki et al., 2008; Moulin et al., 2008). Retrograde plastid signaling can be induced in germinating seedlings by adding either norflurazon (NF), which causes photooxidative damage, or lincomycin (L), which inhibits plastid translation. Because of the different signaling mechanisms induced by these inhibitors, responses vary depending on the gene assayed (Gray et al., 2003). Used in combination with gun mutants, NF and L can be used to establish the mechanism by which transcription of a nuclear gene is responsive to plastid retrograde signals.

To determine whether GLK genes respond to retrograde signals from the plastid, we measured transcript levels in the wild type, glk1 glk2, and gun1 gun5 double mutants grown in the presence or absence of plastid inhibitors. The gun1 gun5 double mutant exhibits an enhanced gun phenotype compared with the respective single mutants (Mochizuki et al., 2001). To verify that the treatments and genotypes were performing as expected, we monitored transcript levels of Lhcb6, RbcS1, and CARBONIC ANHYDRASE1 (CA1), all of which are highly sensitive to plastid signals (Strand et al., 2003). Transcript levels of these genes were downregulated in response to NF and L, and this effect was strongly suppressed by the gun1 gun5 mutations. This suggests that in treated wild-type plants, the GUN signaling pathway mediates the observed response to NF and L (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

GLK Transcript Levels Are Sensitive to Plastid-Derived Retrograde Signals.

RNA gel blot analysis showing accumulation of GLK1, GLK2, RbcS1, CA1, and Lhcb6 transcripts in response to inhibitor-induced plastid damage. Surface-sterilized seeds were sown on media supplemented with 5 μM NF (top panel) or 0.5 mM L (bottom panels). Ten micrograms of total RNA was loaded per lane, and replicate blots were hybridized with 32P-labeled DNA fragments. Blots were visualized by autoradiography and quantified by densitometry. Values below each blot denote the fold-change relative to the wild type grown without inhibitors, standardized to 25S rRNA on the ethidium bromide–stained gel. This experiment was performed twice with similar results.

Interestingly, GLK1 and GLK2 were differentially affected by the gun1 gun5 mutations, even in the absence of plastid inhibitors: GLK1 transcripts accumulated to higher levels in the gun1 gun5 background than in wild type, whereas the reverse was true for GLK2. This observation implies distinct regulation of each gene, a suggestion that is further supported by the differential response of GLK1 and GLK2 to NF- and L-mediated plastid damage. While NF and L led to much lower transcript levels of both genes in the wild type, the gun1 gun5 mutations strongly rescued this effect on GLK2 but only weakly rescued the effect on GLK1. Intriguingly, we found that the transcript size of GLK1 was consistently reduced in wild-type plants treated with NF and L, whereas the transcript size of GLK2 and other genes was unaffected (Figure 10). This result has not been observed under any other conditions previously investigated and may indicate some form of posttranscriptional regulation of GLK1. Together, these observations imply that both GLK1 and GLK2 respond to the developmental status of the chloroplast and that each may be sensitive to different cues.

In monitoring the control genes, we noticed that Lhcb6, RbcS1, and CA1 were less responsive to plastid inhibitors in glk1 glk2 mutants than in the wild type (Figure 10). Specifically, RbcS1 and CA1 transcript levels were higher in mutants than in the wild type following L or NF treatment. This result could be interpreted to suggest that glk1 glk2 mutants exhibit a weak gun-like phenotype. This notion is consistent with the reduced levels of chlorophyll intermediates in glk1 glk2 mutants, a metabolic state that could perturb the tetrapyrrole pool and thus influence the GUN pathway (Mochizuki et al., 2008; Moulin et al., 2008; von Gromoff et al., 2008).

DISCUSSION

The chloroplast is a metabolically and functionally dynamic organelle. During the day, varying levels of light interception must be carefully balanced with rates of carbon fixation, and at night, photosynthesis halts and the chloroplast mobilizes starch reserves. While many of these changes are mediated by rapid posttranslational control, the circadian rhythm of numerous photosynthesis-related transcripts indicates that transcriptional control in the nucleus is a significant factor. We have shown here that GLK transcription factors help regulate the synchronous transcription of a suite of genes required for the light-dependent steps of photosynthesis, in both the light and the dark. We also show that GLK genes themselves respond to retrograde signals from the chloroplast and that at least some of the components of the GLK pathway act independently of the phyB signaling pathway. As such, GLK transcription factors act as nuclear regulators of photosynthetic capacity.

A number of transcription factors have previously been reported to coregulate photosynthesis-related genes, but only GLK proteins have been shown to primarily affect such targets. For example, the bZIP protein HY5 acts downstream of the photoreceptors to regulate photomorphogenesis, of which the concerted transcription of photosynthesis-related genes is just one aspect (Oyama et al., 1997). Although genes required for photosynthesis are highly overrepresented among HY5 targets compared with the genome as a whole, the majority of HY5 targets are other transcription factors. This balance reflects the position of HY5 as a high-level regulator of photomorphogenesis (Lee et al., 2007). Moreover, because hy5 mutants are defective in root growth and hormone response, HY5 must have additional roles beyond photomorphogenesis (Oyama et al., 1997; Cluis et al., 2004). HY5 binding sites, primarily G-box elements, are highly represented in the promoters of other transcriptions factors, including GLK2, but intriguingly not GLK1 (Lee et al., 2007).

Of the two, GLK2 is much more responsive to early light induction in a phy-dependent manner (Tepperman et al., 2006). Since HY5 acts downstream of phy, it seems reasonable to suppose that HY5 activates GLK2 and, furthermore, that GLK transcription factors regulate a more specific subset of genes than early components of the classical photomorphogenesis pathway. Another example of G-box binding transcription factors that coordinate photosynthetic gene expression is the phytochrome interacting factor (PIF) family (Castillon et al., 2007). PIF3 regulates a large number of genes during photomorphogenesis, including CHLH and CAO (Monte et al., 2004), whereas the direct binding of PIF1 is limited to a G-box in the PORC promoter (Moon et al., 2008). Whether GLK proteins work in conjunction with these other transcription factors remains to be established, but given that GLK proteins can interact with G-box binding factors (Tamai et al., 2002), it is unlikely that they act in isolation.

Our results conflict with a recent assessment of the GLK1 regulon, which consisted of a microarray analysis of a GLK1-overexpressing line in a wild-type background (Savitch et al., 2007). The authors reported that GLK1 overexpression induced the expression of a variety of disease- and defense-related genes but had no effect on photosynthesis-related genes. We believe this discrepancy to be the result of three factors. First, expression in a wild-type background would reduce the sensitivity of the experiment in that the plants are already photosynthetically competent. Second, strong constitutive GLK expression leads to pleiotropic effects, such as delayed flowering, leaf epinasty, and increased anthocyanin accumulation, the latter of which may be indicative of stress (Waters et al., 2008; data not shown). Third, constitutive gene expression confounds primary and secondary effects, a situation that was overcome in our study using an inducible expression approach. It is noteworthy, however, that Savitch et al. (2007) reported significant upregulation of MRU1 and LTP, consistent with our findings.

Primary versus Secondary Effects of GLK Action

The use of an inducible gene expression system circumvented many problems associated with direct transcriptome comparisons between genotypes as a means for determining GLK function. Nevertheless, a 4-h induction time conceivably is sufficient for events downstream of immediate GLK activity to become apparent. ChIP assays confirmed that GLK1 protein is associated with the promoters of the most significantly affected genes following GLK induction, implying that such genes are likely to be primary targets. Accordingly, we infer that affected genes whose promoters do not interact with GLK1 (such as COR15a) are indirect, secondary targets of GLK genes. Notably, although a clear aspect of the glk1 glk2 mutant phenotype is the decreased abundance of thylakoid membranes and grana, none of the known components of the thylakoid biogenesis machinery, such as FZL (Gao et al., 2006) or VIPP1 (Kroll et al., 2001; Aseeva et al., 2007), were activated by GLK expression. This implies that reduced thylakoid abundance in glk1 glk2 mutants is a secondary effect of reduced LHC and chlorophyll levels.

One model for the formation of granal thylakoids suggests that attractive forces between LHCII trimers on closely appressed thylakoids cause membrane adhesion (Allen and Forsberg, 2001; Standfuss et al., 2005). Another suggestion is that the crystalline arrays of PSII complexes that form on thylakoid membranes when LHC is bound may assist the assembly of grana (Kovacs et al., 2006). Support for a mechanistic role for LHC and chlorophyll in granal formation is provided by the rice (Oryza sativa) mutant non-yellow coloring1 (nyc1). During senescence, LHCII and chlorophyll are selectively retained in nyc1, and the mutant also maintains thylakoid membranes with a high degree of granal stacking (Kusaba et al., 2007). NYC1 encodes a putative chlorophyll b reductase enzyme responsible for the early stages of chlorophyll b degradation. It is thus likely that retention of LHCII in the nyc1 mutant is a consequence of LHCII stabilization by chlorophyll b (Kusaba et al., 2007) and that grana are maintained in senescent leaves of as a result of that stabilization. Accordingly, by coordinating expression of Lhc and chlorophyll biosynthesis genes, GLK transcription factors promote the formation of stable LHCII-PSII supercomplexes and, hence, the formation of grana.

GLK genes strongly upregulate components of the chlorophyll pathway, in particular HEMA1, CHLH, CRD1, and CAO (Figure 4). Transcriptional profiles of the entire metabolic pathway in Arabidopsis revealed that these four genes are tightly coregulated: they are strongly and synchronously induced during photomorphogenesis, and they cycle in-phase with one another, and with Lhcb1, under circadian control (Matsumoto et al., 2004). Notably, while much of the fine-tuning of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis is performed by posttranslational mechanisms (Tanaka and Tanaka, 2007), these four key genes are under transcriptional regulation, and GLK genes are at least partially responsible for this process.

GLK genes also promote the expression of all three POR genes. However, interpreting the impact of this role is difficult because different POR gene expression profiles have been reported in the literature. For example, one report suggested that both PORA and PORB are active in dark-grown seedlings, but PORA is rapidly repressed upon light exposure and only PORB remains active (Armstrong et al., 1995). However, Matsumoto et al. (2004) reported that both PORA and PORB levels decline rapidly after the onset of light, yet both are active and under circadian control in mature plants. PORC, meanwhile, is induced by light along with the majority of the tetrapyrrole enzymes (Matsumoto et al., 2004) and is thought to have an active role in mature leaves together with PORB (Frick et al., 2003). Regardless of the precise expression patterns of POR genes, coordinated induction by GLK genes implies that all three share a common regulatory element and demonstrates that GLK transcription factors regulate much of the chlorophyll pathway in both the dark and the light.

GLK Targets beyond Chlorophyll and Light Harvesting

While 13 of the 20 genes listed in Table 1 are chloroplast localized, several have unknown function and ambiguous location but are predicted to be GLK1 targets based on ChIP data (Figure 7). For example, MRU1 is strongly induced and encodes a 58–amino acid protein with no recognized functional domains (Goto and Naito, 2002). WoLF PSORT weakly predicts that MRU1 is targeted to the mitochondrion, followed by equal probability of being targeted to the chloroplast, cytosol, or peroxisome. Similarly, the lipid transfer protein (LTP) encoded by At5g48490 putatively functions in lipid binding and transport (Lascombe et al., 2008), which may reflect a requirement for thylakoid lipids. The increased expression of COR15a and a thylakoid lumen-resident rhodanese-like domain-containing protein (At2g42220) following GLK induction is particularly intriguing. COR15a is a cold-induced stromal protein that increases tolerance to freezing temperatures by protecting stromal enzymes from frost damage (Nakayama et al., 2007).

The link to photosynthesis in nonacclimated plants is unclear. However, decreased COR15a protein and transcript levels are observed in mutants with impaired chloroplast development (Nakayama et al., 2007), and levels are downregulated sixfold in a chlorophyll biosynthetic mutant lacking Mg-Proto methyltransferase (Pontier et al., 2007). These findings suggest that expression of COR15a is responsive to broad changes in chloroplast composition and supports our supposition that COR15a is an indirect target of GLK proteins. Rhodaneses, meanwhile, have unknown biological functions in plants, but they catalyze the transfer of sulfur atoms to nucleophilic acceptors, and at least one rhodanese is located in the thylakoids (Bauer et al., 2004). It is conceivable that rhodanese-like proteins may be required for the repair or synthesis of iron-sulfur clusters, such as those found in PSI and in the Rieske protein of the cytochrome b6/f complex (Balk and Lobrèaux, 2005). Given the role of GLK genes in contributing to photosystem assembly, characterization of these rhodaneses may provide insight into how GLK proteins ensure that photosynthetic capacity is optimized in different environmental and developmental conditions.

GLK Function in the Context of Whole-Plant Physiology

Within a plant, leaves are developmentally heterogeneous and are exposed to different light regimes. Shaded leaves, for example, are thinner than leaves exposed to frequent full sun, and shaded chloroplasts contain more chlorophyll b and grana to optimize light harvesting (Anderson et al., 1995; Weston et al., 2000). Such long-term developmental variation implies regulation of photosynthesis at a transcriptional level. Notably, GLK-overexpressing plants accumulate more chlorophyll and chlorophyll-related/Lhc transcripts than the wild type, while RbcS transcripts remain unchanged: this implies a distinct regulation of the balance between the light-dependent steps of photosynthesis and carbon fixation. Such shifts in balance are observed in Arabidopsis acclimating to a transition from high to low light intensity, when light becomes limiting for photosynthesis (Walters and Horton, 1994).

Thus, the GLK overexpression phenotype may be interpreted as mimicking a response to limiting light and hints at an adaptive function for GLK genes. The photosynthetic apparatus responds to changes in light intensity and quality mainly through shifts in the redox balance in the chloroplast (Walters, 2005; Pfannschmidt et al., 2009). A redox-sensitive kinase, such as STN7, is certainly responsible for short-term acclimation through state transitions (Bellafiore et al., 2005) and may also be a candidate for signaling to the nucleus for long-term transcriptional changes that regulate photosystem stoichiometry (Bonardi et al., 2005).

Data presented here suggest that long-term developmental responses to light intensity are not wholly GLK dependent (Figure 1). This observation suggests that while GLK proteins are required for absolute levels of nuclear photosynthetic gene expression, they operate alongside additional regulatory factors that mediate redox signaling. It remains to be established whether GLK genes themselves respond to changes in photosynthetic conditions. Given that GLK genes are sensitive to feedback signaling from the chloroplast (Figure 10), they may operate downstream of plastid retrograde signaling to form part of a more long-term acclimatory response.

The fact that various photoreceptor mutants acclimate normally (Walters et al., 1999) shows that redox signaling rather than photoreceptor signaling mediates changes in photosystem stoichiometry. Nevertheless, both red and blue photoreceptors are required for normal chloroplast biogenesis, especially during deetiolation (Sullivan and Deng, 2003). If GLK and phyB operated in the same direct pathway, we would expect to observe an epistatic relationship in the triple mutant. The additive phenotype of the triple mutant may result from phyB acting partly through GLKs and partly through other factors, while GLKs are responsive to phyB and other regulators (e.g., phyA). This is consistent with the well-characterized PIF-dependent pathways and microarray studies showing that both phyA and phyB regulate GLK transcription (Tepperman et al., 2006). Furthermore, photosynthetic gene expression is especially compromised in glk1 glk2 mutants in blue light, which suggests that cryptochromes also regulate GLK activity and is consistent with the role of cryptochromes in regulating chlorophyll biosynthesis (Stephenson and Terry, 2008). Experiments to investigate these interactions more precisely are underway. However, it is notable that GLK2, but not GLK1, is strongly induced in etiolated seedlings exposed to 45 min of blue light (AtGenExpress light data set, available at http://www.Arabidopsis.org).

The microarray data presented here and previous work (Waters et al., 2008) have shown that the two GLK proteins are functionally equivalent. However, results shown here (Figure 10) and elsewhere (Tepperman et al., 2006) suggest that GLK1 and GLK2 are differentially regulated at the transcriptional level. While the proteins may be capable of performing similar functions, differential transcription may explain the existence of a duplicated gene pair, with one being coexpressed with additional genes to perform a specific function. Recently, GLK1 was implicated as a central component in the signaling network for organic nitrogen metabolism (Gutiérrez et al., 2008), and GLK1 was predicted to promote expression of a cytosolic Gln synthetase, At3g17820. Although we detected no significant change in expression of this gene in our experiments, it is quite conceivable that organic nitrogen status would influence photosynthetic gene expression. Therefore, the possibility that GLK genes respond to organic nitrogen as a regulatory input should be considered further. Additional roles for individual GLK proteins may emerge through similar studies of systems biology.

METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia-0 was used in all experiments. The glk1 glk2 mutant as previously described (Fitter et al., 2002) is available from the European Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC ID N9807). 35S:GLK1 and 35S:GLK2 plants were described previously (Waters et al., 2008). The phyB glk1 glk2 triple mutant was generated by crossing glk1 glk2 with phyB-9, a null allele containing a G-to-A transition that introduces a premature stop codon at amino acid position 397. The allele was originally described as hy3-EMS142 (Reed et al., 1994). The gun1 gun5 double mutant has been described previously (Mochizuki et al., 2001). All seeds were imbibed and stratified for 3 d in the dark at 4°C. Seeds were sown on peat-based compost and transferred to individual 42-mm peat plugs (Jiffy Products International). Plants were grown under a 16-h-light and 8-h-dark photoperiod in the greenhouse at 20 to 25°C with supplementary lighting. For controlled growth conditions (data for Figure 1), plants were grown in a Fitotron PG1400.

The activator line LhGR-N(4c), carrying a single copy of the 35S:LhGR-N construct (Craft et al., 2005), was crossed with the glk1 glk2 mutant. The dark-green F1 progeny were selected on kanamycin and selfed. The F2 generation was screened for pale green individuals representing glk1 glk2 homozygotes. These individuals were selfed, and F3 seed was then sown on kanamycin to identify lines homozygous for 35S:LhGR-N. Seedlings homozygous for glk1, glk2, and 35S:LhGR-N were transformed by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Details of vector construction are given in the Supplemental Methods online. Transgenic plants resistant to hygromycin were selected on 1× Murashige and Skoog (MS) salts with 1× Gamborg's vitamins, 20 μg/mL hygromycin B, and 0.8% (w/v) agar. Plants were grown at 20°C under white light (85 μmol quanta·m−2·s−1) from fluorescent bulbs.

Light and Plastid Inhibitor Treatments

Surface-sterilized seeds were sown on 1× MS salts, 1× Gamborg's vitamins, and 0.8% (w/v) agar and wrapped in foil before stratification in the dark for 3 d at 4°C. Germination was stimulated by a 2-h exposure to white light, and the seeds were then double-wrapped in foil and moved to a growth room at 20°C for a further 48 h. After this time, seedlings were exposed to 16 h of continuous light. Red and blue light was supplied by an array of Luxeon III StarHex LEDs (Philips Lumileds) mounted in a temperature-controlled incubator maintained at 20°C and installed in a dark room. Both red and blue light were delivered at 20 μmol quanta·m−2·s−1, with peak output at 627 and 455 nm respectively, as defined by the manufacturer. For this experiment (Figure 9), white light was supplied by fluorescent tubes at 40 μmol quanta·m−2·s−1. Tissue was harvested either in the dark or under the specific light conditions used for growth, as appropriate. For treatment of seedlings with plastid inhibitors (Figure 10), seeds were grown in the same manner except that the media was supplemented with 1% (w/v) sucrose. When the foil was removed, the seedlings were exposed to white light (60 μmol quanta·m−2·s−1) with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle for two complete cycles. Tissue was harvested at the beginning of the third cycle.

Growth of Seedlings for Microarray Induction Experiments

Full details are given in the Supplemental Methods online. Briefly, seeds were surface sterilized, resuspended in sterile 0.1% (w/v) agar, and transferred by pipette onto 10-cm square plates containing 1× MS salts, 1× Gamborg's vitamins, 20 μg/mL hygromycin B, and 0.8% (w/v) agar. Excess water was allowed to evaporate, and the seeds were stratified.

After 10 d of growth under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle, ∼100 seedlings of equivalent developmental stage were transferred from the plates into 100 mL liquid MS medium in a 250-mL conical flask. The flasks were shaken under the same growth conditions as before. After 48 h of growth in liquid culture, the seedlings were treated with either 10 μM DEX or with 0.1% DMSO (mock induction) and then returned to the same growth conditions. Once the relevant time period had elapsed, seedlings were harvested and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Microarray Experiments and Data Analysis

Seedlings carrying either pOp6:GLK1 or pOp6:GLK2 constructs were grown and treated as described above. For each construct, seedlings were transferred into two separate liquid cultures, which were grown in parallel and treated identically except that one flask was treated with DEX and one mock-treated with DMSO. Each pair of flasks representing an independent biological replicate (four per construct) was grown and treated on different days to control for unintentional day-to-day experimental bias. Treatment was performed 6 h after subjective dawn on each experimental occasion. Details of microarray hybridizations and data analysis are in the Supplemental Methods online.

RNA Analysis

All RNA was isolated by guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform extraction (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 2006), except for the data shown in Figure 9, for which a method more suitable for young Arabidopsis seedlings was employed (McCormac et al., 2001). For microarray analysis, RNA was further purified with an RNeasy plant RNA extraction kit (Qiagen). RNA gel blots were prepared and hybridized in 0.45 M NaCl at 65°C using 32P-labeled DNA fragments as described previously (Langdale et al., 1988). RNA gel blots were quantified using a Bio-Rad FX molecular imager and the supplied Quantity One software. Band intensity was determined using the peak count after background subtraction and was normalized to either the 18S rRNA peak count following hybridization or 25S rRNA band on an ethidium bromide–stained gel. Such bands were quantified using a Kodak EDAS-290 camera with the 1D Image Analysis software (Eastman Kodak). The band with the most intense signal was assigned a value of 1, and the hybridization values were standardized accordingly. DNA probes are detailed in the Supplemental Methods online.

ChIP Assays

ChIP assays were performed as described previously (Saleh et al., 2008) with modifications. Formaldehyde cross-linked chromatin complexes were extracted from 3-week-old 35S:GLK1 plants and sheared to small fragments of ∼500 bp (200 to 1000 bp) by sonication. Antibody against Arabidopsis GLK1 (see Supplemental Methods online for purification procedure) and salmon sperm DNA/protein A agarose beads (Upstate) were used for immunoprecipitation. The coprecipitated DNA was eluted, reverse cross-linked, purified, and finally amplified using primers specific to the promoter regions of the candidate genes. Sequences of PCR primers, which amplify fragments within 500 bp of the ATG in each case, are provided in Supplemental Table 8 online.

Analysis of Chlorophyll Precursors

Approximately 80 mg of dry Arabidopsis seed was surface sterilized and sown on MS plates containing 0.8% (w/v) agar. Using equal amounts of seed, each genotype was considered the most appropriate standardization method, since the hypocotyl and root contribute more to the seedling mass than the cotyledons in the dark, and differences in growth rates may skew the data if measured on a per-weight basis. Following pretreatment of 2 d at 4°C in the dark and 8 h in the light at 24°C, seedlings were grown in the dark at 24°C for 4 d, after which ALA or DP feeding solution (10 mM ALA or DP in 5 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0) was added to each plate. The seedlings were further incubated overnight and harvested under dim green light. Chlorophyll precursors were extracted from etiolated seedlings with N, N-dimethylformamide for 12 h at 4°C in darkness, as described previously (Moran and Porath, 1980). The supernatant was collected by centrifugation for 5 min at 13,000g. Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded from 560 to 700 nm using an LS50 luminescence spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer) at room temperature. The samples were excited at 440, 420, and 400 nm for detection of Pchlide, MgProtoIX/MgProtoIX ME, and Proto IX, respectively.

Transmission Electron Microscopy