Abstract

The tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) protein kinase Pto confers resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato bacteria expressing the AvrPto and AvrPtoB effector proteins. Pto specifically recognizes both effectors by direct physical interactions triggering activation of immune responses. Here, we used a chemical-genetic approach to sensitize Pto to analogs of PP1, an ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitor. By using PP1 analogs in combination with the sensitized Pto (Ptoas), we examined the role of Pto kinase activity in effector recognition and signal transduction. Strikingly, while PP1 analogs efficiently inhibited kinase activity of Ptoas in vitro, they enhanced interactions of Ptoas with AvrPto and AvrPtoB in a yeast two-hybrid system. In addition, in the presence of PP1 analogs, Ptoas bypassed mutations either at an autophosphorylation site critical for the Pto-AvrPto interaction or at catalytically essential residues and interacted with both effectors. Moreover, in the presence of the PP1 analog 3MB-PP1, a kinase-deficient form of Ptoas triggered an AvrPto-dependent hypersensitive response in planta. These findings suggest that, rather than phosphorylation per se, a conformational change likely triggered by autophosphorylation in Pto and mimicked by ligand binding in Ptoas is a prerequisite for recognition of bacterial effectors. Following recognition, kinase activity appears to be dispensable for Pto signaling in planta. The chemical-genetic strategy applied here to develop specific small molecule inhibitors of Pto represents an invaluable tool for the study of biological functions of other plant protein kinases in vivo.

Protein kinases regulate a wide variety of cellular processes and signal transduction pathways in plants. The large number of protein kinases present in plant proteomes (>1,000 in Arabidopsis, >1,500 in rice) makes it a very difficult challenge to assign precise roles to each individual kinase (1, 2). To study protein kinase functions, strategies based on single knock-out mutations and gene silencing are widely employed. However, such efforts are often compromised by lethality, in the case of essential genes, or by functional redundancy and cellular homeostasis. Cell-permeable inhibitors that are highly specific for individual protein kinases would allow overcoming the limitations of genetic approaches to enzyme inactivation and thus represent invaluable tools for assisting in the definition of plant kinase functions. However, while small molecule inhibitors have been recently developed in great numbers for animal protein kinases, their use in the study of plant kinases is still very limited.

Specific kinase inhibitors would be particularly useful for elucidating modes of activation and signaling of protein kinases that serve as receptors in plant innate immunity. Two major classes of receptors detect pathogen invasion and activate immunity in plants (3, 4). One class consists of pattern recognition receptors that are located on the plant cell surface and detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns, which are conserved in many microbes (5). Among the few pattern recognition receptors that have been isolated to date, the receptors of bacterial flagellin and elongation factor Tu encode transmembrane proteins with a cytoplasmic kinase domain (6, 7). The second class of receptors involved in plant innate immunity is represented by resistance (R)3 proteins that specifically recognize virulence proteins, which are commonly referred to as pathogen effectors (8). Kinase catalytic domains are found in certain R proteins either without any additional functional domain (e.g. tomato Pto) or in combination with extracellular leucine-rich repeats and transmembrane domains (e.g. rice Xa21 and barley Rpg1 and Rpg5) (9, 10).

The tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) R protein Pto encodes a serine/threonine protein kinase and confers immunity to the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst) expressing either AvrPto or AvrPtoB (11). During pathogenesis, AvrPto and AvrPtoB are among the ∼30 Pst effector proteins that are delivered into the host cell by the bacterial type III secretion system to promote disease and interfere with host immunity (12-17). Pto specifically recognizes the presence of AvrPto and AvrPtoB in the plant cell by direct physical interactions that result in the activation of the hypersensitive response (HR), an array of defense responses including cell death at the site of pathogen infection (11, 18). Pto-mediated immunity requires the nucleotide binding site/leucine-rich repeats (NBS-LRR) protein Prf that associates with Pto in a high molecular weight complex (19). Functional screens based on virus-induced gene silencing identified MAP kinase cascades and additional signaling proteins acting downstream of the Pto/Prf complex (20, 21).

Extensive biochemical studies revealed the ability of Pto to autophosphorylate at multiple sites and to phosphorylate substrate proteins in vitro (22, 23). However, the role of Pto kinase activity in recognition of bacterial effectors and signal transduction has been controversial for a long time and not yet entirely resolved. Early studies examined the requirement of Pto kinase activity for effector recognition by analyzing the effect of point mutations at conserved catalytic residues or autophosphorylation sites on the Pto-AvrPto or Pto-AvrPtoB physical interaction in a yeast two-hybrid system (23-26). In most instances kinase-deficient forms of Pto did not interact with AvrPto or AvrPtoB, suggesting a requirement of Pto kinase activity for effector recognition; however, a few exceptions supported opposite conclusions (25, 26). More recently, structural and in vitro biochemical analysis suggested that stabilization of the Pto P+1 loop by phosphorylation at Thr-199 is a prerequisite for AvrPto recognition (27). As for the role of Pto kinase activity in signal transduction, evidence that kinase activity is dispensable after effector recognition derived from constitutive gain-of-function Pto mutants that elicit HR in an effector-independent manner, while not displaying kinase activity in vitro (25, 26). In contrast, Pto kinase activity appears to be required for signaling based on a mutation at the Pto autophosphorylation site Ser-198, which is required for the elicitation of the HR but dispensable for the interaction with AvrPto (23).

To elucidate further the role of Pto kinase activity in recognition of AvrPto and AvrPtoB, and in effector-dependent activation of immune responses, we used a chemical-genetic approach that renders a given kinase uniquely susceptible to analogs of 1-tert-butyl-3-p-tolyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-ylamine (PP1), an ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitor (28, 29). In this approach, substitution of a conserved and bulky residue, termed the gatekeeper residue, with alanine or glycine generates a unique pocket in the ATP binding site of the kinase of interest, which is not present in any wild-type kinase. The sensitized mutant can then be selectively and potently inhibited by ATP-competitive small molecules that contain substituents occupying the novel pocket. This strategy has been successfully applied to specifically inhibit catalytic activity of protein kinases from multiple organisms including plants, yeast, and mammalian cell cultures by using PP1 analogs (29-33).

We previously engineered the Pto ATP-binding site to contain a unique enlarged binding pocket while retaining catalytic activity (34). In the analog-sensitive Pto allele (Ptoas) the gate-keeper residue was mutated to alanine (Y114A) and a second site mutation (L68I) was introduced to rescue the severely reduced kinase activity of Pto(Y114A) (34). In the present study, we confirmed that Ptoas displays functional properties of wild-type Pto and is specifically targeted by PP1-derived small-molecule inhibitors. Binding of PP1 analogs to the enlarged ATP-binding site of Ptoas resulted in specific inhibition of kinase activity in vitro, yet surprisingly allowed kinase-deficient forms of Ptoas to bind bacterial effectors in yeast and to elicit an effector-dependent HR in planta. These results, interpreted in combination with structural data (27), suggest that a conformational change, possibly elicited by autophosphorylation in wild-type Pto and mimicked by binding of PP1 analogs in Ptoas, enables Pto to recognize bacterial effectors. In addition, our findings support the notion that kinase activity is dispensable for Pto-mediated signal transduction. Finally, the chemical-genetic strategy used here for Pto may be applied to the in vivo study of other plant protein kinases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Site-directed Mutagenesis—Mutagenesis of Pto was performed in the shuttle vector pTEX containing the Pto coding region under the control of the Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter (35), or in the plasmids pGEX-4T1 and pEG202, containing the Pto coding region fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) and to the LexA DNA binding domain, respectively (22, 23). Site-specific mutations were introduced using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene). Sequences of oligonucleotides used for mutagenesis are listed in supplemental Table S1. The insertion in the gene of the desired mutations was confirmed by sequencing.

Protein Expression in Escherichia coli—Constructs for the expression in E. coli of MPK2 as a maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion and of Pto, Ptoas, Pti1, and the kinase-deficient mutant Pti1(K96N) as GST fusions were described previously (22, 34, 36, 37). GST fusions were expressed in the E. coli strain DH12S grown to A600 = 1. Expression of recombinant proteins was induced by 0.05 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 6 h at 24 °C. GST fusion proteins were then affinity-purified by using glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma). Expression in E. coli and purification of MBP fusions with amylose resin were performed according to the instructions of the manufacturer (New England Biolabs).

Kinase Activity Assays—Kinase assays to test autophosphorylation of Pto forms, Pti1, and MPK2 were performed in vitro with 2 μg of the recombinant kinase in 20 μl of kinase reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 10 mm MnCl2, and 20 mm ATP) containing 1 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham Biosciences). When testing phosphorylation of Pti1(K69N) by Pto forms, 2 μg of GST-Pti1(K69N) was included in the reaction mixture. PP1 analogs were synthesized as described (38, 39) and their effect on kinase activity was tested at the final concentration of 1 μm. As a control, assays were performed in the absence of inhibitors with an equivalent volume of DMSO. Reactions were incubated for 10 min at room temperature and stopped by the addition of 10 mm EDTA. At this time, phosphate incorporation was found to be linear for the amount of enzyme used in the reaction. Proteins were then fractionated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250, and the dried gel was analyzed by Phosphorimager (Fujifilm FLA-2000) or exposed to autoradiography. IC50 values for the PP1 analogs 3MB-PP1, 1NM-PP1, 2Na-PP1, and Ac-PP1 were determined by measuring the counts per minute of 32P transferred by GST-Ptoas to GST-Pti1(K96N). Various inhibitor concentrations ranging from 1 nm to 1 μm were added to kinase reactions performed as described above. IC50 values were calculated as the concentration of inhibitor at which 32P incorporation into GST-Pti1(K96N) was 50% of that in control reactions carried out in the absence of inhibitor.

Yeast Two-hybrid Assays—Yeast two-hybrid interactions were tested in the yeast strain EGY48 using standard protocols (40). Yeast were transformed sequentially with the lacZ reporter plasmid pSH18 -34, the bait plasmid pEG202 expressing LexA DNA-binding domain fused to wild-type or mutant Pto, and the prey plasmid pJG4 -5 expressing the GAL4 activation domain fused either to AvrPto, AvrPtoB1-387 or their mutant forms. The Pto bait vector as well as the AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387 prey vectors were described previously (37, 41, 42). Quantitative assays for β-galactosidase activity were performed as described (43), except that yeast cells were grown in minimal medium supplemented with 2% galactose, 1% raffi-nose, and lacking uracil, histidine, and tryptophan. To test their effect on protein-protein interactions, PP1 analogs or an equal volume of DMSO as control, were added to the liquid growth media at the indicated concentrations. Expression in yeast of LexA fusion proteins was determined by Western blot analysis using LexA antibodies (Upstate) and chemiluminescent visualization, as previously described (35).

Agrobacterium-mediated Transient Expression—Expression cassettes containing Pto forms driven by the CaMV 35S promoter and followed by the Nos terminator were excised by the EcoRI restriction enzyme from the pTEX shuttle vector and inserted at the corresponding site of the binary vector pBTEX (35). pBTEX plasmids were introduced into Agrobacterium GV2260 by electroporation. Before inoculation, Agrobacterium strains were grown overnight at 28 °C in Luria broth medium with the appropriate antibiotics and washed in infiltration medium (10 mm morpholinoethanesulfonic acid, 10 mm MgCl2 and 0.2 mm acetosyringone). For co-expression of Pto forms with AvrPto or AvrPtoB, Agrobacterium strains expressing Pto forms were mixed with strains carrying the plasmids pBTEX: avrPto (35) or pBTEX:avrPtoB (24) at a final A600 = 0.06 each, and infiltrated into leaves of 6-8-week-old N. benthamiana or tomato (S. lycopersicum) plants. The tomato cultivars used in this study are Rio Grande PtoS (RG-PtoS; pto/pto; Prf/Prf) lacking a functional Pto gene (11), and Rio Grande prf3 (RG-prf3; Pto/Pto; prf/prf) carrying a mutation in the Prf gene (45).

To test the effect of the PP1 analogs in planta, N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with Agrobacterium carrying the indicated gene constructs in the pBTEX binary vector and were treated 20 h after infiltration with a solution containing 100 μm 3MB-PP1, or DMSO as control, and 0.025% Silwet-77. The solution was applied using a fine brush. The HR developed within 48-72 h after infiltration, and the severity of the symptoms was recorded with scores from 1 to 5 (where 1 = no symptoms and 5 = cell death in the whole infiltrated area). An HR index reflecting the degree of symptoms developed by each Pto mutant in the different treatments, as compared with wild-type Pto, was calculated according to Equation 1 (23).

In this formula, the entries within the brackets are the scores for symptoms caused by the expression of the indicated proteins, and PtoM represents the specific mutant tested.

RESULTS

Ptoas Kinase Activity Is Specifically and Potently Inhibited by ATP-competitive Small Molecules—We have previously reported the engineering of an analog-sensitive form of Pto (Ptoas), which retains catalytic activity despite containing an enlarged ATP-binding site (34). Because of the enlarged ATP-binding pocket, Ptoas is predicted to be sensitized to specific inhibition by ATP-competitive small molecules, such as analogs of the kinase inhibitor PP1 (46). In this study, we set out to use a combination of Ptoas and specific small molecule inhibitors to assess the role of Pto kinase activity in recognition of Pst effectors and signal transduction.

To identify specific and potent small molecule inhibitors of Ptoas kinase activity, we screened a panel of various PP1 analogs (supplemental Fig. S1) for their ability to inhibit in vitro Ptoas and wild-type Pto autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of the substrate Pti1(K96N). As shown in Fig. 1A, all the inhibitors examined, with the exception of 2NM-PP1 and aMB-PP1, specifically inhibited the ability of Ptoas to phosphorylate Pti1(K96N), while having negligible effect on wild-type Pto. Similar results were obtained for Ptoas and wild-type Pto autophosphorylation (data not shown). IC50 values were then determined for analogs that at a concentration of 1 μm showed over 75% inhibition of Ptoas kinase activity (3MB-PP1, 1NM-PP1, 2Na-PP1, and Ac-PP1). 1NM-PP1 and 3MB-PP1 were the most potent inhibitors with IC50 values of 120 and 160 nm, respectively (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

PP1 analogs specifically inhibit Ptoas kinase activity. A, in vitro phosphorylation of the kinase-deficient mutant GST-Pti1(K96N) by GST-Pto (white bars) and GST-Ptoas (gray bars) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and the indicated PP1 analogs (1 μm). Kinase activity in the presence of inhibitors is measured as percentage of that observed in the absence of inhibitors. Data are the means of three technical repeats ± S.E. The assay was repeated at least two times for each inhibitor with similar results. B, in vitro autophosphorylation of GST-Pti1 and MBP-MPK2 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and the indicated PP1 analogs at 1 μm or at IC50 values determined for GST-Ptoas activity, as indicated in Table 1. Kinase activity in the presence of inhibitors is measured as percentage of that observed in the absence of inhibitors (DMSO). Data are the means of three technical repeats ± S.E.

TABLE 1.

50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of selected PP1 analogs for Ptoas kinase activity

Inhibition assays were carried out by testing GST-Pti1 (K96N) phosphorylation by GST-Ptoas in the presence of various inhibitor concentrations ranging from 1 nm to 1 μm.

| Inhibitor | IC50a |

|---|---|

| nm | |

| 1NM-PP1 | 120 |

| 3MB-PP1 | 160 |

| 2Na-PP1 | 250 |

| Ac-PP1 | 350 |

IC50 is defined as the concentration of the inhibitor at which Ptoas kinase activity was 50% of the control (no inhibitor).

To further confirm the specificity of 1NM-PP1 and 3MB-PP1 to Ptoas, we tested in vitro the ability of these PP1 analogs to inhibit activity of the tomato serine/threonine kinase Pti1 and of the MAP kinase MPK2, which were previously proposed to participate in signaling pathways downstream of Pto (20, 37). The effect of the two inhibitors was tested at concentrations corresponding to their IC50 values for Ptoas and at 1 μm. As shown in Fig. 1B, 1NM-PP1 and 3MB-PP1 were not able to significantly inhibit Pti1 and MPK2. Because of their potency and specificity to Ptoas, these ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitors were selected for subsequent functional analysis of Pto.

Ptoas Displays Functional Properties of Wild-type Pto—Functional properties of Pto include its ability to elicit the HR when co-expressed with the Pst effectors AvrPto or AvrPtoB in N. benthamiana and tomato plants, respectively (24, 41). In addition, Pto physically interacts with AvrPto and AvrPtoB in a yeast two-hybrid system (24, 41). To validate the use of Ptoas in the present study, we tested whether this Pto variant displays functional properties similar to wild-type Pto. The competence of Ptoas to elicit the HR was assessed using an Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression assay in N. benthamiana plants and in the tomato line RG-PtoS that do not contain a recognition determinant for AvrPto and AvrPtoB, respectively (24, 47). Co-expression of Ptoas and AvrPto in N. benthamiana, or co-expression of Ptoas and AvrPtoB in RG-PtoS caused the development of a typical HR in the inoculated areas within 48 h (Fig. 2, A and B). The appearance of the HR elicited by co-expression of Ptoas with AvrPto or AvrPtoB was similar in timing and intensity to that caused by expression of wild-type Pto in combination with the same effectors. Leaf areas expressing either Pto, Ptoas, AvrPto, or AvrPtoB alone exhibited no response. In addition, the HR caused by co-expression of Pto and AvrPtoB in tomato was dependent on a functional Pto pathway because it was not induced in RG-prf3 plants carrying a mutation in the Prf gene, which is required for Pto signaling (45) (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Ptoas is functional in the elicitation of the HR and interacts with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387. A and B, elicitation of the HR by Ptoas. N. benthamiana (A) or RG-PtoS and RG-prf3 tomato leaves (B) were infiltrated in the encircled areas with Agrobacterium strains for the expression of the indicated proteins. Leaves were photographed 72 h after inoculation. Tissue collapse in the infiltrated areas reflects elicitation of the HR. C, physical interactions of Pto (gray bars) and Ptoas (white bars) with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387 measured in a yeast two-hybrid system. Data are the means of three independent yeast transformants ± S.E. The assay was repeated three times with similar results. D, expression of bait proteins in yeast. Pto and Ptoas were expressed in yeast as LexA fusions and visualized in immunoblots with anti-LexA antibodies.

Next, a yeast two-hybrid system was used to test the ability of Ptoas to physically interact with AvrPto or with the N-terminal domain of AvrPtoB (AvrPtoB1-387), which is sufficient to interact with Pto and to elicit Pto-dependent immunity (42). The variable expression of full-length AvrPtoB in yeast hindered its use in these experiments (data not shown and Ref. 12). As shown in Fig. 2C, Ptoas interacted with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387, albeit at lower levels than wild-type Pto. Pto and Ptoas bait fusion proteins accumulated in yeast at similar levels excluding the possibility that the weaker interactions of Ptoas with effectors was a result of reduced Ptoas expression (Fig. 2D). Together, these results indicate that Ptoas retains functional properties of wild-type Pto, although it displays weaker physical interactions with Pst effectors.

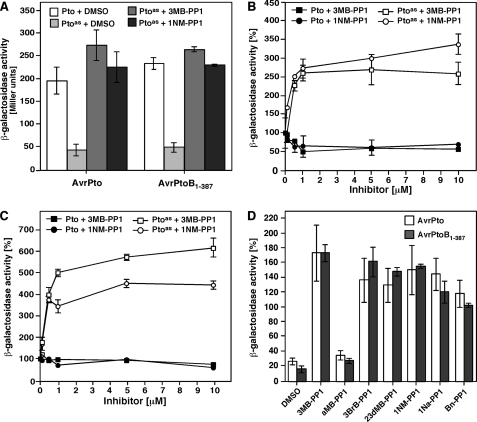

PP1 Analogs Enhance Physical Interactions of Ptoas with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387—The reduced interactions of Ptoas with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387 correlated well with a 70% decrease in catalytic activity previously observed for Ptoas relative to wild-type Pto (34). In an attempt to assess whether kinase activity is required for the interaction of Pto with Pst effectors, we monitored the physical interaction of Ptoas with AvrPto or AvrPtoB1-387 in a yeast two-hybrid system in the presence of the two potent and specific inhibitors of Ptoas kinase activity identified in vitro, 3MB-PP1 and 1NM-PP1. Unexpectedly, the addition of either 3MB-PP1 or 1NM-PP1 did not inhibit the interactions of Ptoas with the Pst effectors (Fig. 3A), even at a concentration of 10 μm that completely inhibited kinase activity of Ptoas in vitro (Fig. 1 and data not shown), and blocked the activity of typical analog-sensitized kinases in yeast (29, 48). Instead, 3MB-PP1 and 1NM-PP1 significantly potentiated the interactions of Ptoas with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387 (Fig. 3A). Dose-response curves revealed that the increase in interactions reaches saturation at a drug concentration of ∼1 μm (Fig. 3, B and C). Interestingly, at saturation levels the strength of Ptoas interactions with both effectors approached that of wild-type Pto (Fig. 3, A-C). The ATP-competitive small molecules did not increase the interactions of wild-type Pto with the Pst effectors and the binding potentiation effect was thus specific for the drug-sensitized mutant (Fig. 3, A-C).

FIGURE 3.

PP1 analogs enhance interactions of Ptoas with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387. A, interactions of Pto and Ptoas with AvrPto or AvrPtoB1-387 measured in a yeast two-hybrid system in the presence of 3MB-PP1 (10 μm), 1NM-PP1 (10 μm) or DMSO using the β-galactosidase assay. B and C, dose-response effect of 3MB-PP1 and 1NM-PP1 on the interaction of Pto and Ptoas with AvrPto (B) or AvrPtoB1-387 (C). β-Galactosidase activity is reported as percentage of the activity observed for each bait-prey combination in the presence of DMSO. D, interactions of Ptoas with AvrPto (white bars) or AvrPtoB1-387 (gray bars) in the presence of the indicated PP1 analogs (10 μm). Activity is reported as percentage of that observed for the interaction of Pto with AvrPto or AvrPtoB1-387 in the presence of the same analog. In each panel, data are the means of three independent yeast transformants ± S.E. Assays were repeated at least three times with similar results.

To test whether additional PP1 analogs have a similar effect to 3MB-PP1 and 1NM-PP1 on Ptoas, we screened structurally similar compounds (supplemental Fig. S1) for their ability to affect the interactions of Ptoas with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387. As shown in Fig. 3D, all the PP1 analogs tested, with the exception of aMB-PP1, enhanced the interactions of Ptoas with both Pst effectors to levels comparable with those of wild-type Pto. The ability of these PP1 analogs to affect Ptoas-effector interactions correlated well with the potency of their inhibition against Ptoas in vitro kinase activity (Fig. 1). This strongly supports the notion that the binding of PP1 analogs to the active site of Ptoas underlies their potentiating effects on Ptoas-effector interactions.

Kinase Activity Is Dispensable for Ptoas Interactions with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387 in the Presence of PP1 Analogs—A positive rather than negative effect of the PP1 analogs on Ptoas protein-protein interactions suggested that in their presence Ptoas does not require kinase activity to interact with AvrPto or AvrPtoB1-387. However, it remains possible that the residual level of Ptoas kinase activity in the presence of the inhibitors is sufficient to carry out the phosphorylation required for Pto-effector interactions. To directly test this possibility, we generated kinase-deficient forms of Ptoas by further mutating catalytically essential residues in the kinase. To this end, mutations were introduced in Ptoas at the invariant residue Lys-69 of the kinase subdomain II, which is involved in ATP binding, or at the conserved Asp-182 of the DFG motif in the kinase subdomain IV, which is required for binding of divalent cations (49). As expected, Ptoas(K69R) and Ptoas(D182E) did not autophosphorylate or phosphorylate the Pto substrate Pti1(K96N) in a kinase assay in vitro (Fig. 4A) and lost their ability to interact with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387 in a yeast two-hybrid system (Fig. 4, B and C). However, the addition of 3MB-PP1 or 1NM-PP1 to the yeast growth medium rescued the interactions of the Ptoas kinase-deficient variants with both Pst effectors (Fig. 4, B and C). In the presence of 3MB-PP1 and 1NM-PP1, the interaction of Ptoas(D182E) with either AvrPto or AvrPtoB1-387 was ∼80 and 60% of wild-type Pto, respectively. Interactions of Ptoas(K69R) with the two Pst effectors were only partially restored by the PP1 analogs to 10-20% of the wild-type level (Fig. 4, B and C). These results suggest that the binding of ATP-competitive small molecules to Ptoas renders the kinase activity dispensable for its interactions with AvrPto or AvrPtoB1-387.

FIGURE 4.

3MB-PP1 and 1NM-PP1 drugs rescue the interactions of Ptoas kinase-deficient forms with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387. A, kinase activity assay of Pto variants. Autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of GST-Pti1(K96N) by the indicated GST-Pto forms was tested in vitro, and proteins were fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained by Coomassie Blue (bottom panel) and exposed to autoradiography (top panel). B and C, interactions of Pto forms with AvrPto (B) or AvrPtoB1-387 (C) measured in a yeast two-hybrid system in the presence of 3MB-PP1 (10 μm), 1NM-PP1 (10 μm), or DMSO using the β-galactosidase assay. β-Galactosidase activity is reported as percentage of that observed for the interaction of Pto with AvrPto or AvrPtoB1-387 in the presence of DMSO. Data are the means of three independent yeast transformants ± S.E. The assay was repeated three times with similar results. D, expression of bait proteins in yeast in the presence or absence of 10 μm 3MB-PP1. Wild-type and mutant forms of Pto were expressed in yeast as LexA fusions and visualized in immunoblots with anti-LexA antibodies.

To exclude the possibility of an indirect effect of the PP1 analogs on the expression and stability of Pto variants in yeast, protein levels of the various Pto bait forms were determined by immunoblot analysis using antibodies raised against the LexA fusion. As shown in Fig. 4D, steady-state levels of all Pto forms were not affected by the presence of 3MB-PP1 at a concentration of 10 μm, which was the highest concentration used in the yeast two-hybrid experiments.

PP1 Analogs Bypass Ptoas Autophosphorylation at Thr-199 and Their Effect Is Dependent on a Pto-AvrPto Natural Interface—Autophosphorylation at Pto Thr-199 was previously shown to be important for Pto recognition of AvrPto and was proposed to be necessary for stabilization of the Pto P+1 loop (23, 27). To examine whether the effect of autophosphorylation at Pto Thr-199 is also bypassed by PP1 analogs, we generated the mutant Ptoas(T199A) and tested its interactions with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387. Ptoas(T199A) was severely impaired in its ability to bind AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387 (Fig. 5, A and B), while still retained a similar kinase activity in vitro as Ptoas and Pto(T199A) (Fig. 5C). However, the addition of either 3MB-PP1 or 1NM-PP1 to the yeast growth medium completely rescued the ability of Ptoas(T199A) to interact with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387, whereas it did not affect the interactions of Pto(T199A) with the Pst effectors (Fig. 5, A and B). Immunoblots performed using anti-LexA antibody confirmed that steady-state levels of Pto mutants in yeast were not affected by the presence of 10 μm 3MB-PP1 (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that the effect of autophosphorylation at Thr-199 on Pto-effector interactions can be bypassed by binding of PP1 analogs to the enlarged Ptoas ATP-binding site.

FIGURE 5.

3MB-PP1 and 1NM-PP1 rescue the interactions of Ptoas(T199A) with bacterial effectors, but not the interaction of Ptoas with AvrPto(I96T). A and B, interactions of Pto forms with AvrPto (A) or AvrPtoB1-387 (B) measured in a yeast two-hybrid system in the presence of 3MB-PP1 (10 μm), 1NM-PP1 (10 μm), or DMSO using the β-galactosidase assay. β-Galactosidase activity is reported as percentage of that observed for the interaction of Pto with AvrPto or AvrPtoB1-387 in the presence of DMSO. Data are the means of three independent yeast transformants ± S.E. The assay was repeated three times with similar results. C, kinase activity assay of Pto forms. Autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of GST-Pti1(K96N) by the indicated GST-Pto forms was tested in vitro, and proteins were fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained by Coomassie Blue (bottom panel) and exposed to autoradiography (top panel). D, expression of bait proteins in yeast in the presence or absence of 10 μm 3MB-PP1. Wild-type and mutant forms of Pto were expressed in yeast as LexA fusions and visualized in immunoblots using anti-LexA antibodies. E, interactions of Pto and Ptoas with AvrPto or AvrPto(I96T) in the presence of 3MB-PP1 (10 μm), 1NM-PP1 (10 μm), or DMSO. Data are the means of three independent yeast transformants ± S.E. The assay was repeated three times with similar results.

The recent crystal structure determination of the Pto-AvrPto complex revealed that a main interface that mediates the interaction of the two proteins is between the P+1 loop of Pto and the GINP motif of AvrPto (27). In addition, introduction of mutations in the GINP motif of AvrPto hampers the interaction of the mutant effector with Pto in a yeast two-hybrid system (50). To verify that the ability of Ptoas to bind AvrPto in the presence of ATP-competitive drugs is mediated by this natural interface, we tested the interaction of Ptoas with the GINP motif mutant AvrPto(I96T) in the yeast two-hybrid system. As expected, both wild-type Pto and Ptoas were unable to interact with AvrPto(I96T) (Fig. 5E). Addition of 3MB-PP1 or 1NM-PP1 to the yeast growth medium did not rescue these interactions. These results indicate that rescue of the Ptoas-AvrPto interaction by PP1 analogs is dependent on and occurs through a natural interaction interface between Pto and AvrPto.

Kinase Activity Is Dispensable for Pto Signaling in Planta—We next investigated the requirement of Pto kinase activity for effector-dependent signaling in planta by exploiting the ability of PP1 analogs to bypass the requirement of kinase activity for the interactions of Pto with bacterial effectors. Specifically, we tested whether expression of AvrPto and kinase-deficient forms of Ptoas is sufficient for elicitation of the HR in the presence of PP1 analogs. To this aim, Pto, Ptoas, and its kinase-deficient variants Ptoas(D182E) and Ptoas(K69R) were each co-expressed with AvrPto in N. benthamiana leaves using an Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression assay. Twenty hours after infiltration of Agrobacterium suspensions, leaves were treated with either 100 μm of 3MB-PP1 or DMSO as control, and monitored for the appearance of tissue collapse and cell death that is characteristic of the HR. Finally, to estimate the extent of cell death, an HR index was calculated for each Ptoas variant and treatment (DMSO or 3MB-PP1) and normalized to that of wild-type Pto.

As expected, in the presence of DMSO or 3MB-PP1, expression of AvrPto and Pto elicited a typical HR (Fig. 6A). Similarly, Ptoas was functional in elicitation of the HR, although its HR index was 20 and 10% lower than that of wild-type Pto in the presence of DMSO and 3MB-PP1, respectively (Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, the kinase-deficient variants Ptoas(D182E) and Ptoas(K69R) were severely impaired in induction of the HR in the presence of DMSO (Fig. 6, A and B). Remarkably, addition of 3MB-PP1 significantly recovered the HR-inducing ability of Ptoas(D182E) to ∼50% of wild-type Pto, while it caused a milder increase in the HR index of Ptoas(K69R) to ∼30% (Fig. 6, A and B). The quantitatively different effect of 3MB-PP1 on the HR-inducing activity of the two kinase-deficient Ptoas variants well correlated with the differential ability of the drug to restore their physical interactions with AvrPto and AvrPtoB1-387 (Fig. 4, B and C). It should be noted that the rescue effect of 3MB-PP1 on Ptoas(D182E) and Ptoas(K69R) was absolutely dependent on the expression of AvrPto (supplemental Fig. S2), thus excluding the possibility that this drug renders the Ptoas kinase-deficient variants constitutively active and independent of AvrPto activation. Together, these results suggest that following the physical interaction between Pto and AvrPto, Pto kinase activity is dispensable for Pto signaling in planta.

FIGURE 6.

Elicitation of the HR by expression of Ptoas mutants and AvrPto in N. benthamiana leaves in the presence of 3MB-PP1. A, N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with Agrobacterium strains for the expression of either AvrPto and the indicated Pto form or AvrPto alone (empty). Infiltrated areas were treated 20 h after infiltration with 3MB-PP1 or DMSO as control. The HR was visualized as localized tissue collapse typically within 2-3 days. B, HR index reflecting the efficiency of the indicated Ptoas form and treatment (3MB-PP1 or DMSO) in the elicitation of the HR. The HR index was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures” and included at least 51 independent observations for each mutant. Data are the means ± S.E.

DISCUSSION

We used a chemical-genetic strategy to develop small molecule inhibitors that specifically target the kinase activity of the tomato R protein Pto. These highly selective inhibitors allowed us to shed new light on the controversial role of Pto kinase activity in recognition of Pst effectors and signal transduction. The results of this study, interpreted in combination with structural data (27), suggest a novel form of protein kinase regulation: kinase activity is required to stabilize Pto in the proper conformation for interacting with the AvrPto and Avr-PtoB bacterial effectors, but is dispensable for Pto-mediated signal transduction.

Small molecule inhibitors are widely used for the functional study of animal protein kinases, but very few pharmacological tools are available for plant protein kinases. The challenge of inhibitor specificity is more pronounced in the plant kinases since there are >1,000 kinases in plant genomes compared with roughly half the number in human and mouse genomes (1, 2, 51). To develop the first specific inhibitor of Pto, we utilized a chemical-genetic approach to inhibitor development that has been widely and successfully applied to examine cellular functions of several kinases from different organisms and revealed kinase-dependent and -independent functions of these proteins (29, 31-33, 52). An important advantage of this approach is that Ptoas retains molecular properties qualitatively similar to those of wild-type Pto. At the same time, Ptoas kinase activity can be rapidly and reversibly inactivated by cell-permeable small molecule inhibitors. In contrast, other approaches, which were previously used for addressing the role of kinase activity for Pto function, involved mutants that are irreversibly impaired in one or more molecular properties, thus complicating interpretation of the results. For example, Pto mutants in kinase catalytic residues are kinase-deficient, most of them do not interact with AvrPto and are not functional in the elicitation of the HR (25, 41, 47). Similarly, constitutively active Pto forms that activate an effector-independent HR do not interact with effectors and are impaired in kinase activity (25, 26).

Potent and specific inhibitors of Ptoas selected from a panel of PP1 analogs allowed us to examine the role of kinase activity in Pto recognition of the AvrPto and AvrPtoB effectors. Previous reports based on biochemical and structural data suggested that phosphorylation at Thr-199 in the P+1 loop of the Pto activation domain plays an important role in the recognition of bacterial effectors (23, 27). Phosphorylation at Thr-199 was proposed to stabilize Pto conformation and to represent a prerequisite for its interaction with AvrPto (27). Here we show that PP1 analogs, while efficiently inhibiting the kinase activity of the protein in vitro, potentiated the interaction of Ptoas with the bacterial effectors in a dose-dependent fashion up to wild-type Pto levels. Moreover, the inhibitors rescued the interactions of the kinase-deficient Ptoas(D182E) and of the P+1 loop mutant Ptoas(T199A) with AvrPto and AvrPtoB. However, their effect was less prominent on the interactions between the kinase-deficient Ptoas(K69R) and the effectors. We can speculate that this is the result of a lower affinity of the PP1 analogs to the mutant kinase due to the central position of Lys-69 in the ATP binding site as opposed to Asp-182, which is located on its out-skirts (27). Thus, the ability of the small molecule ligands to bypass Pto kinase activity and activation-domain phosphorylation further supports the notion that an active conformation, rather than a docking phosphorylated residue(s), is critical for the interactions of Pto with effectors.

The molecular mechanism that allows PP1 analogs to potentiate the interaction of Ptoas with bacterial effectors remains to be determined. We first hypothesized that PP1 analogs could affect Ptoas stability or create a novel unnatural interface between Ptoas and effectors. However, these possibilities are unlikely because 3MB-PP1 did not affect Ptoas steady-state levels in yeast and the effect of PP1 analogs on the Ptoas-AvrPto interaction was dependent on a natural interface. An alternative scenario is that PP1 analogs induce in Ptoas a conformational change that leads to stabilization of the activation loop mimicking the effect of phosphorylation at Thr-199 in wild-type Pto. This hypothesis is supported by the evidence that PP1 analogs bypass the need of phosphorylation at Thr-199 for a proper Pto-AvrPto interaction. Finally, the possibility that PP1 analogs stimulate interaction with effectors by mimicking the ATP-bound form of the kinase should also be considered, although this is less likely based on the evidence that Ptoas(T199A) displays a very weak interaction with effectors while still retaining kinase activity, which implies ATP binding.

Bypassing the need of kinase activity with ATP-competitive small molecules is not unprecedented. In a study aimed at the dissection of its kinase function, the yeast ER stress sensor Ire1 was sensitized to inhibition of PP1 derivatives (33). Interestingly, in the presence of its kinase domain ligand 1NM-PP1, the sensitized Ire1 bypassed mutations that inactivate its kinase activity and was fully functional in the activation of unfolded protein response (33). The effect of 1NM-PP1 on the sensitized Ire1 was attributed to a conformational change and/or to a change in the oligomeric state of the enzyme similar to that caused by binding of ADP to the wild-type kinase (33). In the case of Ire1, it contains an endonuclease domain in addition to the kinase domain. The endonuclease activity mediates the majority of the signaling output from Ire1 while the kinase activity primarily modulates the endonuclease activity. In contrast, Pto contains only the catalytic activity of a protein kinase and is a monoenzyme. Our results that binding of a small-molecule ligand could bypass catalytic activity of a monoenzyme kinase argue against the stereotypic view of protein kinases relying on their enzymatic activity for signaling output. The effect of PP1 analogs on Ptoas and Ire1as might be part of a wider phenomenon that could apply to other protein kinases. Understanding the structural basis of this phenomenon may lead to the identification of additional kinases that can be switched to an active conformation by small molecule ligands, bypassing the need of their kinase activity. This may allow the elaboration of strategies for the chemical regulation of certain protein kinase functions by small molecules that selectively bind to their kinase ATP-binding site.

The effect of PP1 analogs on Pto-effector interactions was specific for Ptoas and independent on the identity of effector protein. This confirms that the conformational requirements of Pto for the recognition of AvrPto and AvrPtoB are similar, in agreement with previous reports showing that different Pto variants, including chimeras of Pto with the related kinase Fen, mutants in autophosphorylation sites and surface-exposed residues, interacted with AvrPto and AvrPtoB with similar specificity (24, 26).

By a combination of small molecule ligands directed at the kinase active site and a kinase-deficient form of Ptoas we provide evidence supporting the notion that kinase activity is dispensable for signaling by Pto in planta. In fact, bypassing the requirement of Pto kinase activity for the interaction with AvrPto was sufficient for a Ptoas kinase-deficient form to trigger an AvrPto-dependent HR in N. benthamiana plants. This is the first time that a kinase-deficient variant of Pto is shown to activate an effector-dependent HR and demonstrates that PP1 analogs can be used in planta for the pharmacological regulation of Pto functions. Our data are consistent with a conformational change induced in Pto by AvrPto, switching it from an inactive to an active state. In addition, they confirm that the inhibitory effect on Pto kinase activity that was recently shown for AvrPto in vitro (27) does not play a role in Pto activation.

The molecular mechanisms used by Pto to relay the signal conveyed by effector recognition are still unknown. Early studies proposed that Pto initiates signaling pathways by phosphorylation of downstream proteins (37, 44, 53). Although in vitro substrates of Pto phosphorylation have been identified, there is no direct evidence in vivo that corroborates this hypothesis. More recently, Pto has been shown to interact in vivo with the NBS-LRR protein Prf in a high molecular protein complex (19). The Pto-Prf interaction and additional genetic and molecular data support a model in which Pto signals by regulating Prf function (19, 27). Our findings that kinase-deficient Ptoas activates an effector-dependent HR in the presence of PP1 analogs argues against the model of Pto signaling through phosphorylation of downstream proteins. In addition, they suggest that Pto transphosphorylation activity is not absolutely required in mechanisms of Pto signaling, including the proposed activation of Prf, but may play an auxiliary role. This is in agreement with previously published results showing that constitutively active Pto mutants that lack kinase activity in vitro induce an effector-independent but Prf-dependent HR in planta (25, 26). However, it is still possible that phosphorylated residues may play a role in stabilizing the Pto-activated form. A possible candidate residue for such a role could be the Pto autophosphorylation site Ser-198, which was shown to be required for the elicitation of the HR, but dispensable for the interaction with AvrPto (23).

In conclusion, the emerging picture from results of the current study and previous investigation is that Pto kinase activity plays an important role through autophosphorylation in the stabilization of the Pto molecule in the proper conformation for interacting with bacterial effectors, but not in Pto-mediated signal transduction. Pto appears to rely on a switch between conformation states to convey the signal: the protein is first activated by an effector-induced conformational change, which is subsequently sensed by Prf to activate plant immune responses. Finally, the chemical-genetic strategy used here to develop small-molecule inhibitors that specifically target the kinase activity of Pto represents an invaluable means for the definition of biological functions of other plant kinases, for which available pharmacological tools are very limited.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gregory B. Martin for plasmid constructs, and Robert Fluhr and Naomi Ori for critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by Binational Science Foundation Grants 2001124 and 2007091.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: R, resistance; CaMV, Cauliflower mosaic virus; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HR, hypersensitive response; MBP, maltose-binding protein; NBS-LRR, nucleotide binding site/leucine-rich repeats; PP1, 1-tert-butyl-3-p-tolyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-ylamine; Pst, Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato; Ptoas, analog-sensitive Pto; RG, Rio Grande.

References

- 1.Dardick, C., Chen, J., Richter, T., Ouyang, S., and Ronald, P. (2007) Plant Physiol. 143 579-586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000) Nature 408 796-815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chisholm, S. T., Coaker, G., Day, B., and Staskawicz, B. J. (2006) Cell 124 803-814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones, J. D. G., and Dangl, J. L. (2006) Nature 444 323-329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zipfel, C. (2008) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20 10-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinchilla, D., Bauer, Z., Regenass, M., Boller, T., and Felix, G. (2006) Plant Cell 18 465-476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zipfel, C., Kunze, G., Chinchilla, D., Caniard, A., Jones, J. D. G., Boller, T., and Felix, G. (2006) Cell 125 749-760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caplan, J., Padmanabhan, M., and Dinesh-Kumar, S. P. (2008) Cell Host Microbe 3 126-135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin, G. B., Bogdanove, A. J., and Sessa, G. (2003) Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54 23-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brueggemana, R., Drukab, A., Nirmalaa, J., Cavileerc, T., Draderd, T., Rostokse, N., Mirlohif, A., Bennypaulg, H., Gilla, U., Kudrnah, D., Whitelawi, C., Kilianj, A., Hank, F., Sunl, Y., Gilla, K., Steffensonm, B., and Kleinhofs, A. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 14970-14975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedley, K. F., and Martin, G. B. (2003) Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 41 215-243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abramovitch, R. B., Kim, Y. J., Chen, S., Dickman, M. B., and Martin, G. B. (2003) EMBO J. 22 60-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohn, J. R., and Martin, G. B. (2005) Plant J. 44 139-154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauck, P., Thilmony, R., and He, S. Y. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 8577-8582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navarro, L., Jay, F., Nomura, K., He, S. Y., and Voinnet, O. (2008) Science 321 964-967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shan, L. B., He, P., Li, J. M., Heese, A., Peck, S. C., Nurnberger, T., Martin, G. B., and Sheen, J. (2008) Cell Host Microbe 4 17-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiang, T. T., Zong, N., Zou, Y., Wu, Y., Zhang, J., Xing, W. M., Li, Y., Tang, X. Y., Zhu, L. H., Chai, J. J., and Zhou, J. M. (2008) Curr. Biol. 18 74-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mur, L. A. J., Kenton, P., Lloyd, A. J., Ougham, H., and Prats, E. (2008) J. Exp. Bot. 59 501-520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mucyn, T. S., Clemente, A., Andriotis, V. M. E., Balmuth, A. L., Oldroyd, G. E. D., Staskawicz, B. J., and Rathjen, J. P. (2006) Plant Cell 18 2792-2806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.del Pozo, O., Pedley, K. F., and Martin, G. B. (2004) EMBO J. 23 3072-3082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekengren, S. K., Liu, Y., Schiff, M., Dinesh-Kumar, S. P., and Martin, G. B. (2003) Plant J. 36 905-917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sessa, G., D'Ascenzo, M., Loh, Y. T., and Martin, G. B. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 15860-15865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sessa, G., D'Ascenzo, M., and Martin, G. B. (2000) EMBO J. 19 2257-2269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim, Y. J., Lin, N. C., and Martin, G. B. (2002) Cell 109 589-598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rathjen, J. P., Chang, J. H., Staskawicz, B. J., and Michelmore, R. W. (1999) EMBO J. 18 3232-3240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu, A. J., Andriotis, V. M., Durrant, M. C., and Rathjen, J. P. (2004) Plant Cell 16 2809-2821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xing, W., Zou, Y., Liu, Q., Liu, J., Luo, X., Huang, Q., Chen, S., Zhu, L., Bi, R., Hao, Q., Wu, J. W., Zhou, J. M., and Chai, J. (2007) Nature 449 243-247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bishop, A. C., Buzko, O., and Shokat, K. M. (2001) Trends Cell Biol. 11 167-172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishop, A. C., Ubersax, J. A., Petsch, D. T., Matheos, D. P., Gray, N. S., Blethrow, J., Shimizu, E., Tsien, J. Z., Schultz, P. G., Rose, M. D., Wood, J. L., Morgan, D. O., and Shokat, K. M. (2000) Nature 407 395-401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bohmer, M., and Romeis, T. (2007) Plant Mol. Biol. 65 817-827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brodersen, P., Petersen, M., Nielsen, H. B., Zhu, S. J., Newman, M. A., Shokat, K. M., Rietz, S., Parker, J., and Mundy, J. (2006) Plant J. 47 532-546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin, S. E., Zhang, C., Kadlecek, T. A., Shokat, K. M., and Weiss, A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 30 15419-15430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papa, F. R., Zhang, C., Shokat, K., and Walter, P. (2003) Science 302 1533-1537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, C., Kenski, D. M., Paulson, J. L., Bonshtien, A., Sessa, G., Cross, J. V., Templeton, D. J., and Shokat, K. M. (2005) Nat. Methods 2 435-441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frederick, R. D., Thilmony, R. L., Sessa, G., and Martin, G. B. (1998) Mol. Cell 2 241-245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pedley, K. F., and Martin, G. B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 49229-49235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou, J., Loh, Y. T., Bressan, R. A., and Martin, G. B. (1995) Cell 83 925-935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benjamin, K. R., Zhang, C., Shokat, K. M., and Herskowitz, I. (2003) Genes Dev. 17 1524-1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bishop, C. B., Kung, C., Shah, K., Witucki, L., Shokat, K. M., and Liu, Y. (1999) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 627-631 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golemis, E. A., Gyuris, J., and Brent, R. (1995) in Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (Ausubel, F. M., Brent, R., Kingston, R. E., Moore, D. D., Seidman, J. G., Smith, J. A., and Struhl, K., eds) Vol. 3, pp. 20.1.1-20.1.28, John Wiley and Sons, New York [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang, X., Frederick, R. D., Zhou, J., Halterman, D. A., Jia, Y., and Martin, G. B. (1996) Science 274 2060-2063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao, F., He, P., Abramovitch, R. B., Dawson, J. E., Nicholson, L. K., Sheen, J., and Martin, G. B. (2007) Plant J. 52 595-614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reynolds, A., and Lundblad, V. (1989) in Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (Ausubel, F. M., Brent, R., Kingston, R. E., Moore, D. D., Seidman, J. G., Smith, J. A., and Struhl, K., eds) Vol. 2, pp. 13.6.1-13.6.4, John Wiley and Sons Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou, J., Tang, X., and Martin, G. B. (1997) EMBO J. 16 3207-3218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salmeron, J. M., Oldroyd, G. E., Rommens, C. M., Scofield, S. R., Kim, H. S., Lavelle, D. T., Dahlbeck, D., and Staskawicz, B. J. (1996) Cell 86 123-133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bishop, A. C., Shah, K., Liu, Y., Witucki, L., Kung, C., and Shokat, K. M. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8 257-266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scofield, S. R., Tobias, C. M., Rathjen, J. P., Chang, J. H., Lavelle, D. T., Michelmore, R. W., and Staskawicz, B. J. (1996) Science 274 2063-2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones, M. H., Huneycutt, B. J., Pearson, C. G., Zhang, C., Morgan, G., Shokat, K., Bloom, K., and Winey, M. (2005) Curr. Biol. 15 160-165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scheeff, E. D., and Bourne, P. E. (2005) PLoS Comput. Biol. 1 e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shan, L., Thara, V. K., Martin, G. B., Zhou, J. M., and Tang, X. (2000) Plant Cell 12 2323-2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quintaje, S. B., and Orchard, S. (2008) Mol. Cell Proteomics 7 1409-1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiss, E. L., Bishop, A., Shokat, K., and Drubin, D. G. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2 677-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gu, Y. Q., Yang, C., Thara, V. K., Zhou, J., and Martin, G. B. (2000) Plant Cell 12 771-786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.