The crystal structure of the G81A mutant form of the chimera of (S)-mandelate dehydrogenase and of its complexes with two of its substrates reveal productive and non-productive modes of binding for the catalytic reaction. The structure also indicates the role of G81A in lowering the redox potential of the flavin co-factor leading to an ∼200-fold slower catalytic rate of substrate oxidation.

Keywords: (S)-mandelate dehydrogenase, membrane proteins, flavoenzymes

Abstract

(S)-Mandelate dehydrogenase (MDH) from Pseudomonas putida, a membrane-associated flavoenzyme, catalyzes the oxidation of (S)-mandelate to benzoylformate. Previously, the structure of a catalytically similar chimera, MDH-GOX2, rendered soluble by the replacement of its membrane-binding segment with the corresponding segment of glycolate oxidase (GOX), was determined and found to be highly similar to that of GOX except within the substituted segments. Subsequent attempts to cocrystallize MDH-GOX2 with substrate proved unsuccessful. However, the G81A mutants of MDH and of MDH-GOX2 displayed ∼100-fold lower reactivity with substrate and a modestly higher reactivity towards molecular oxygen. In order to understand the effect of the mutation and to identify the mode of substrate binding in MDH-GOX2, a crystallographic investigation of the G81A mutant of the MDH-GOX2 enzyme was initiated. The structures of ligand-free G81A mutant MDH-GOX2 and of its complexes with the substrates 2-hydroxyoctanoate and 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate were determined at 1.6, 2.5 and 2.2 Å resolution, respectively. In the ligand-free G81A mutant protein, a sulfate anion previously found at the active site is displaced by the alanine side chain introduced by the mutation. 2-Hydroxyoctanoate binds in an apparently productive mode for subsequent reaction, while 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate is bound to the enzyme in an apparently unproductive mode. The results of this investigation suggest that a lowering of the polarity of the flavin environment resulting from the displacement of nearby water molecules caused by the glycine-to-alanine mutation may account for the lowered catalytic activity of the mutant enzyme, which is consistent with the 30 mV lower flavin redox potential. Furthermore, the altered binding mode of the indolelactate substrate may account for its reduced activity compared with octanoate, as observed in the crystalline state.

1. Introduction

(S)-Mandelate dehydrogenase (MDH) from Pseudomonas putida is a membrane-associated FMN-dependent α-hydroxyacid oxidizing enzyme (Mitra et al., 1993 ▶). It belongs to the monotopic class of integral membrane proteins (Blobel, 1980 ▶), which are inserted into only one side of the phospholipid bilayer. In the case of MDH, 39 residues internal to the mature protein sequence are responsible for binding to the membrane. MDH is found in several strains of pseudomonads as part of a metabolic pathway that helps the organisms to utilize mandelic acid as a source of carbon and energy. It shares a common active-site arrangement and ∼30–45% amino-acid sequence identity with other members of the α-hydroxyacid oxidizing enzyme family (Maeda-Yorita et al., 1995 ▶; Lindqvist et al., 1991 ▶), namely yeast flavocytochrome b 2 (FCB2), spinach glycolate oxidase (GOX), bacterial lactate monooxygenase (LMO) and mammalian long-chain hydroxyacid oxidase (LCHAO) (Lederer, 1991 ▶; Ghisla & Massey, 1989 ▶; Xia & Mathews, 1990 ▶; Le & Lederer, 1991 ▶; Lindqvist et al., 1991 ▶). Most members of this family follow a ping-pong mechanism during the reaction cycle, which comprises two half-reactions. In the first, the reductive half-reaction, the substrate is oxidized by the flavin and in the second, the oxidative half-reaction, the reduced FMN is reoxidized by an electron acceptor. The reductive half-reaction is similar in all members of this family, while the oxidative half-reaction is different, as different oxidants are utilized by individual family members for the reoxidation of flavin. In the case of MDH, the electron acceptor is a member of the electron-transfer chain within the bacterial membrane, possibly a quinone.

To make MDH amenable for crystallization, the 39-residue internal membrane-binding segment of MDH was replaced with a 20-residue segment derived from one of its soluble homologues, GOX (Xu & Mitra, 1999a ▶). This resulted in a soluble chimera of MDH, called MDH-GOX2, which retained the full catalytic activity for substrate oxidation of wild-type MDH. The X-ray structure of MDH-GOX2 at 2.15 Å and subsequently at 1.35 Å resolution has been reported previously (Sukumar et al., 2001 ▶, 2004 ▶). Like the other family members, the catalytic domain forms a β8α8 TIM barrel (Fig. 1 ▶). Like most flavodehydrogenases, reduced MDH reacts relatively slowly with molecular oxygen compared with oxidases such as GOX. A role of the membrane-binding segment in maintaining the slow reoxidation rate was ruled out as the chimera MDH-GOX2 also reacts poorly with oxygen (Xu & Mitra, 1999b ▶). Extensive mutagenic studies have been carried out on the protein environment around the FMN to determine the catalytic roles of the active-site residues in substrate oxidation and the rate of flavin reoxidation by dioxygen (Xu et al., 2002 ▶; Lehoux & Mitra, 1999 ▶, 2000 ▶; Dewanti et al., 2004 ▶).

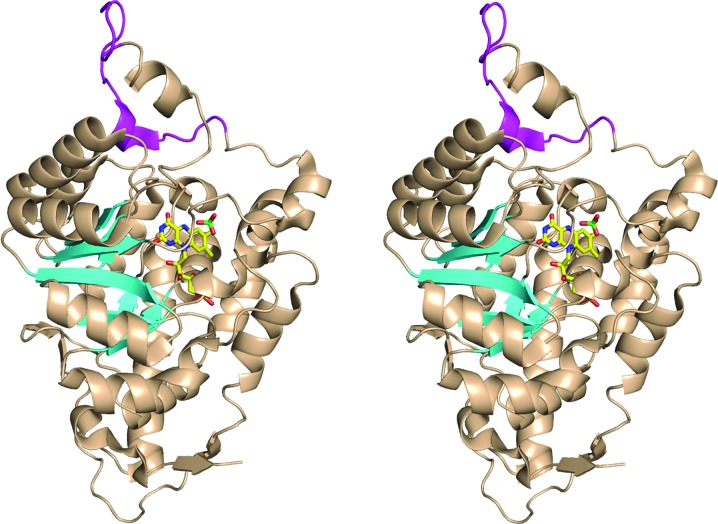

Figure 1.

Ribbon diagram of the chimeric MDH-GOX2 structure (PDB code 1p4c). The portions of the structure derived from wild-type MDH (residues 4–176 and 197–356) are colored wheat, except for the eight β-strands of the β8α8 TIM-barrel motif, which are shown as cyan arrows. The portion of the structure derived from GOX (residues 177–196) is shown in magenta. The FMN and sulfate ion in the active site are shown in ball-and-stick representation, with carbon yellow, oxygen red, nitrogen blue and sulfur green. This diagram was prepared using PyMOL (DeLano, 2002 ▶).

In MDH-GOX2, the conformation and orientation of the FMN are similar to those in GOX and FCB2 (Sukumar et al., 2001 ▶), with its re-face in contact with strand β1 of the TIM barrel and its N5 atom accepting a hydrogen bond from the amide of Gly81, the final residue in a structurally conserved tetrapeptide loop on the re-face of FMN found in all the proteins of this family. This hydrogen bond is retained even in the reduced state of the enzyme (Sukumar et al., 2004 ▶). In both oxidation states of native MDH-GOX2, a sulfate anion is bound in the active site and makes van der Waals contact with the si-face of the flavin ring (Fig. 1 ▶). It forms hydrogen bonds to three nearby side chains that have been implicated in the catalysis of substrate oxidation within the enzyme family, Arg165, His255 and Arg258, and to four water molecules.

Although the FMN of FCB2 virtually superimposes on that of MDH-GOX2, its orientation in GOX is significantly different, being tilted by ∼20° with respect to that in MDH-GOX2 and FCB2. In GOX, there is a water molecule present near the re-face close to O4 of FMN in a site formed by the displacement of the flavin ring. It has been proposed that this water position is the binding site for dioxygen when the flavin becomes reduced and that the dioxygen would then be able to reoxidize the flavin through the formation of a transient covalent peroxo intermediate at position C4A (Lindqvist et al., 1991 ▶).

When comparing the active sites of the α-hydroxyacid enzyme family, it has been found that the residue corresponding to Gly81 in MDH is not strictly conserved, being glycine in the bacterial dehydrogenases and alanine in the oxidases (except for LMO, where it is Gly) and the flavocytochromes, suggesting that this residue might play a role in the reactivity of reduced flavin with molecular oxygen. However, mutagenic studies of the members of this enzyme family have been ambiguous (Sun et al., 1997 ▶; Yorita et al., 1996 ▶; Daff et al., 1994 ▶). To address this question in the MDH system, the G81A mutant forms of both MDH and of MDH-GOX2 were prepared and characterized (Dewanti et al., 2004 ▶), showing that the catalytic activity for the reductive half-reaction of G81A with mandelate and similar substrates was 20–100-fold lower than that of wild-type MDH and MDH-GOX2; this decreased rate correlated to a decreased electrophilicity of FMN in the G81A mutant proteins as indicated by redox-potential measurements (Dewanti et al., 2004 ▶). However, G81A was also found to have two to fivefold higher reactivity with oxygen than the wild type, which is consistent with a role for Gly81 in suppressing the reactivity of the enzyme toward oxygen.

In order to study the mode of substrate binding to MDH-GOX2 in a less reactive enzyme and the possible role of Gly81 in modulating its reactivity towards oxygen, an X-ray diffraction study of this mutant protein and of its complexes with two poor substrates, 2-hydroxyoctanoate and 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate (Fig. 2 ▶, Table 1 ▶), was undertaken. An earlier attempt to prepare a complex between MDH-GOX2 and (S)-mandelate in the crystalline state was not successful since the affinity of the reduced enzyme for the natural substrate (S)-mandelate and for the product benzylformate is low (Sukumar et al., 2004 ▶).

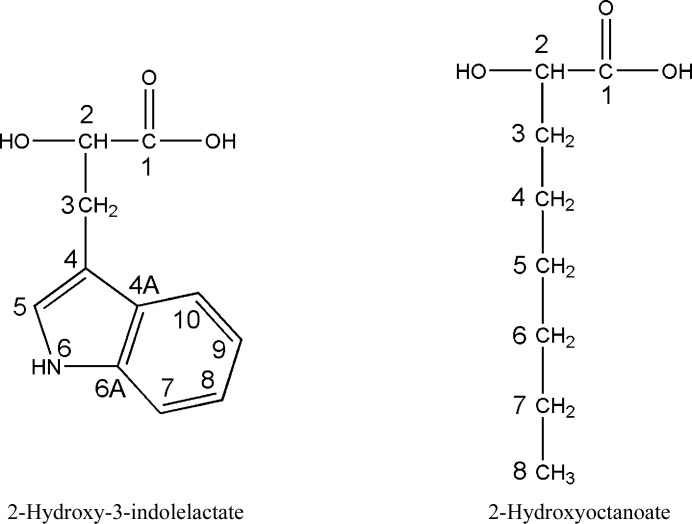

Figure 2.

Chemical formulae of the MDH substrates 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate and 2-hydroxyoctanoate.

Table 1. Comparison of the substrate-specificity of wild-type MDH, MDH-GOX2, MDH G81A and MDH-GOX2 G81A.

Steady-state kinetic parameters were obtained at 293K using (R,S)-mandelate as substrate. Assays were performed in 0.1M potassium phosphate pH 7.5 with 150mM DCPIP, 1mgml1 BSA and 1mM phenazine methosulfate.

| Wild-type MDH | MDH G81A | MDH-GOX2 | MDH-GOX2 G81A | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | k cat (s1) | K m (mM) | k cat (s1) | K m (mM) | k cat (s1) | K m (mM) | k cat (s1) | K m (mM) |

| Mandelate | 350 10 | 0.24 0.02 | 15.2 0.3 | 0.24 0.02 | 205 4 | 0.09 0.01 | 2.3 0.07 | 0.04 0.01 |

| 3-Indolelactate | 1.0 0.01 | 0.9 0.1 | 0.3 0.01 | 0.17 0.01 | 3.9 0.07 | 0.64 0.04 | 1.4 0.05 | 0.13 0.02 |

| 2-Hydroxyoctanoate | 0.5 0.06 | 0.8 0.1 | 0.3 0.01 | 0.14 0.01 | 1.0 0.01 | 0.29 0.01 | 0.42 0.02 | 0.57 0.01 |

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Protein purification and crystallization

The carboxy-terminal histidyl-tagged G81A mutant form of MDH-GOX2 was expressed and purified as described elsewhere (Dewanti et al., 2004 ▶). The G81A crystals were grown by the vapor-diffusion method, as previously described for the MDH-GOX2 chimera (Sukumar et al., 2001 ▶), by mixing 3 µl protein solution (10–15 mg ml−1) with 3 µl precipitation solution and equilibrating against reservoir solution. The precipitation solution contained 0.2 M MES pH 6.2, 0.75% ammonium sulfate, 10% ethylene glycol and 20 µM FMN. The reservoir solution contained 4 M sodium chloride. The crystals grew after 2 d. Once the crystals had attained a suitable size for X-ray diffraction analysis, they were transferred to a holding solution containing 200 mM MES pH 6.2, 0.75% ammonium sulfate, 25% ethylene glycol and 20 µM FMN, in which they were stable for several weeks.

(d,l)-2-Hydroxy-3-indolelactate and (d,l)-2-hydroxyoctanoate were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich and were used for soaking of crystals without further purification.

2.2. Data collection and processing

Three crystals of the G81A mutant form of MDH-GOX2 were prepared for data collection: one of ligand-free G81A and two in complex with the poor substrates 2-hydroxyoctanoate and 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate (Table 1 ▶), respectively. The G81A–2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate and G81A–2-hydroxyoctanoate complexes were prepared by soaking crystals of the G81A mutant protein in holding liquor containing 30 mM 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate for 2 h or 8 mM 2-hydroxyoctanoate for 16 h, respectively.

The ligand-free crystal was mounted directly from the holding solution and was found to suffer from merohedral twinning, as did the ‘native’ MDH-GOX2 crystals and all other crystals of ligand-free G81A mutant proteins that were tested. However, unlike the case of the MDH-GOX2 crystals, in which twinning could be removed by cutting the crystals into equal halves (Sukumar et al., 2001 ▶), the G81A crystal did not show any such propensity. However, soaking the crystals in an artificial mother liquor containing substrates seemed to remove the twinning in some crystals. After testing several crystals, one for each complex was found to be untwinned and was used for further data collection and processing.

The X-ray data for the G81A–2-hydroxyoctanoate complex were collected with an in-house R-AXIS IV detector system mounted on a Rigaku RU-200 rotating-anode X-ray generator using a copper target. The data for the ligand-free G81A crystal and for the G81A–2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate complex crystal were collected on an ADSC Quantum CCD detector at the BioCARS 14BM-C and NE-CAT 8BM beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) of the Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois. Data for all three crystals were recorded by flash-freezing at 100 K with cryoprotection provided by the ethylene glycol present in the holding liquor. The data from the ligand-free and from the 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate and 2-hydroxyoctanoate complex G81A crystals were processed to 1.6, 2.2 and 2.5 Å resolution, respectively (Table 2 ▶).

Table 2. Data collection, structure determination and refinement for G81A.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Ligand-free | Indolelactate complex | Octanoate complex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Wavelength () | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.5418 |

| Space group | I4 | I4 | I4 |

| Unit-cell parameters | |||

| a () | 99.4 | 99.4 | 98.8 |

| b () | 99.4 | 99.4 | 98.8 |

| c () | 87.5 | 87.6 | 87.4 |

| Resolution limit () | 1.6 (1.661.60) | 2.20 (2.282.20) | 2.50 (2.592.50) |

| I/(I) | 28.2 (2.8) | 12.2 (2.5) | 14.9 (1.9) |

| R merge (%) | 4.3 (24.1) | 8.4 (30.2) | 11.8 (77.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 95.5 (66.3) | 94.4 (88.5) | 100 (99.9) |

| Redundancy | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Refinement | |||

| Protocol | CNS | CNS | CNS |

| Resolution range () | 301.6 | 402.2 | 502.5 |

| R factor (%) | 13.6 | 19.8 | 18.9 |

| R free (%) | 17.3 | 24.3 | 25.9 |

| No. of reflections | 51143 | 19200 | 13774 |

| Model | |||

| No. of amino acids | 353 | 353 | 353 |

| No. of water molecules | 284 | 224 | 126 |

| No. of FMN molecules | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No. of MES molecules | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No. of ligand atoms | 0 | 15 | 11 |

| R.m.s. B (2) | 25.3 | 34.9 | 49.7 |

| R.m.s. B (m/m)† (2) | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| R.m.s. B (m/s)† (2) | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| R.m.s. B (s/s)† (2) | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Residues in generously allowed region | 4 (Asp188, Leu189, Asp193, Ser304) | 3 (Ala194, Asn196, Ser285) | 3 (Asp188, Leu189, Ser285) |

| Residues in disallowed regions | 1 (Glu32) | 1 (Glu32) | 1 (Glu32) |

| No. of atoms with zero occupancy | 10 | 10 | 48 |

| Stereochemical ideality | |||

| Bonds () | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.008 |

| Angles () | 1.20 | 1.35 | 1.46 |

Root-mean-square difference in B factor for bonded atoms; m/m, m/c and c/c represent main chainmain chain, main chainside chain and side chainside chain bonds, respectively.

Data processing and scaling were carried out using the program HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶). Crystal twinning was analyzed using Yeates’s web-based twinning-identification program (Yeates, 1997 ▶). Crystal structure refinement was carried out using CNS (Brünger et al., 1998 ▶) and REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997 ▶); electron-density fitting and model building were performed using TURBO-FRODO (Roussel & Cambillau, 1989 ▶) and Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▶) on a Silicon Graphics workstation. Model generation and regularization of 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate and 2-hydroxyoctanoate, as well as their keto-acid products, was performed using the Builder and Discover modules of INSIGHT II (Accelrys Inc., USA) and the Monomer Library Sketcher module of CCP4 (Collaborative Computational Suite, Number 4, 1994 ▶).

2.3. Structure determination and refinement

The high-resolution oxidized MDH-GOX2 structure (Sukumar et al., 2004 ▶) was directly submitted to rigid-body refinement procedures against the twinned substrate-free G81A crystal data. An (F o − F c) difference map yielded clear electron density for the Cβ atom at residue 81, which was subsequently changed from glycine to alanine for further refinement. Statistical analysis of the degree of twinning using CNS indicated a twinning ratio of 0.44/0.56; this ratio was reset to 0.5/0.5 for subsequent refinement as the deviation from perfect twinning was small and the reset value gave slightly better results.

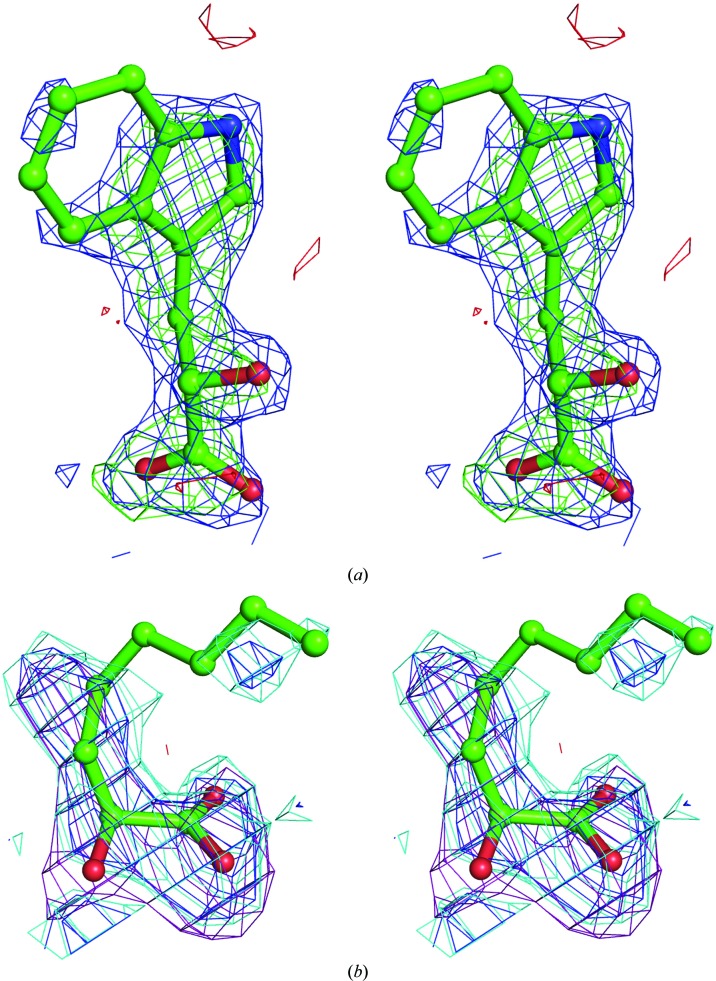

The partially refined G81A model was then used directly for refinement using the indole and octanoate complex data sets. The presence of 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate and 2-hydroxyoctanoate molecules (or their oxidized keto-acid forms) at the active site of the enzyme were clearly indicated in their respective unbiased (F o − F c) and (2F o − F c) difference maps (Fig. 3 ▶).

Figure 3.

Unbiased electron-density difference Fourier maps of the MDH-GOX2 G81A enzyme–substrate complexes computed using (2F o − F c) and (F o − F c) coefficients. (a) 2-Hydroxy-3-indolelactate; the (2F o − F c) map is contoured at the 1σ level (blue) and the F o − F c map at +3σ (green) and −3σ (red). The F c structure factors were computed after refinement of a model containg the full polypeptide chain, FMN and 116 water molecules, none of which were located near the active site. (b) 2-Hydroxyoctanoate; the (2F o − F c) map is contoured at 1σ (blue) and at 0.75σ (cyan), while the (F o − F c) map is contoured at +2.5σ (violet) and −2.5σ (red). The F c structure factors were computed as in (a) except that no water molecules were included in the model. This diagram was prepared using PyMOL (DeLano, 2002 ▶).

All the models were then subjected alternatively to positional and B-factor refinement using CNS. The simulated-annealing refinement and annealed OMIT-map protocol was applied once to each of the models (Hodel et al., 1992 ▶). Throughout the fitting and refinement, the quality of the model was monitored by calculating R free (based on 5% of the reflections; Brünger, 1992 ▶). The subsequent refinement yielded (2F o − F c) electron-density maps for 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate and 2-hydroxyoctanoate that showed clear density for the entire 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate molecule and for the more important head portion of 2-hydroxyoctanoate, while the catalytically less important tail portion of 2-hydroxyoctanoate was poorly ordered, with density visible for this part only at the 0.5σ level. The final stereochemistry of all three structures was checked against the Ramachandran map in PROCHECK (Morris et al., 1992 ▶). A summary of the data analysis, refinement results and stereochemistry is presented in Table 2 ▶.

2.4. Single-crystal polarized absorption microspectrophotometry

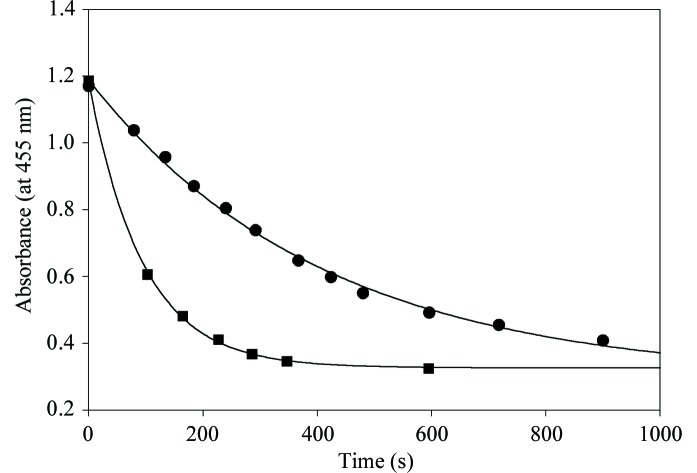

Crystals of the G81A MDH-GOX2 mutant protein were placed in a flow cell with quartz windows and spectral measurements were recorded on a Zeiss MPM800 microspectrophotometer as described previously (Rivetti et al., 1993 ▶; Merli et al., 1996 ▶). Spectra were recorded using plane-polarized light with the electric vector parallel to one or the other of the principal optical directions lying on the crystal face perpendicular to the incident beam. The aqueous surroundings of the crystal were varied by flowing fresh holding solution containing 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate or 2-hydroxyoctanoate at the same concentrations used for X-ray data collection and UV–visible spectra were recorded at regular intervals up to 2 and 18 h, respectively. For kinetic measurements crystals were exposed to the substrates at 4 mM concentration and spectra were recorded at about 1 min intervals in the range 400–550 nm (Fig. 4 ▶).

Figure 4.

Decay plots of the maximum absorbance at 450 nm of crystals of the G81A mutant form of MDH reduced by 2-hydroxyoctanoate (filled circles) and by 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate (filled squares). The first-order rate constants for these two reactions, calculated from the curves, are 0.64 and 0.15 min −1, respectively. These measurements were carried out as described in the text.

3. Results

3.1. Overall structure

In all three structures of the G81A mutant of chimeric MDH-GOX2 (uncomplexed and the octanoate and indole complexes at 1.6, 2.5 and 2.2 Å resolution, respectively), the polypeptide backbone could be traced from residues Asn4 to Glu356 in the (2F o − F c) electron-density maps and refined. However, portions of the side chains for several residues in each structure (two side chains for G81A, two for G81A–indole and about a dozen for G81A–octanoate; Table 2 ▶) could not be fitted to the weak electron density and were assigned zero occupancy. As in the case of the native MDH-GOX2, the first three and last 24 residues of the cloned sequence, including an engineered hexahistidyl tag at the C-terminus, are also absent. Also as observed in the oxidized and reduced forms of MDH-GOX2 (Sukumar et al., 2001 ▶, 2004 ▶), one residue, Glu32, adopts a disallowed conformation in G81A and its two complexes. A similar feature was observed in the structures of closely related members of this family such as GOX (Lindqvist, 1989 ▶) and FCB2 (Xia & Mathews, 1990 ▶).

The three G81A structures closely resemble the structure of MDH-GOX2 (Sukumar et al., 2001 ▶, 2004 ▶). However, unlike the native MDH-GOX2 structures there is no sulfate anion bound at the active site of any of the G81A structures. The r.m.s. deviation in Cα positions between both the reduced and oxidized forms of MDH-GOX2 with respect to the G81A mutant protein is 0.20 Å for all 353 amino-acid residues; the r.m.s. deviation in α-carbon positions between free G81A and its octanoate and indole complexes are 0.30 and 0.31 Å, respectively.

3.2. Comparison of the free G81A mutant protein with the reduced and oxidized MDH-GOX2 structures

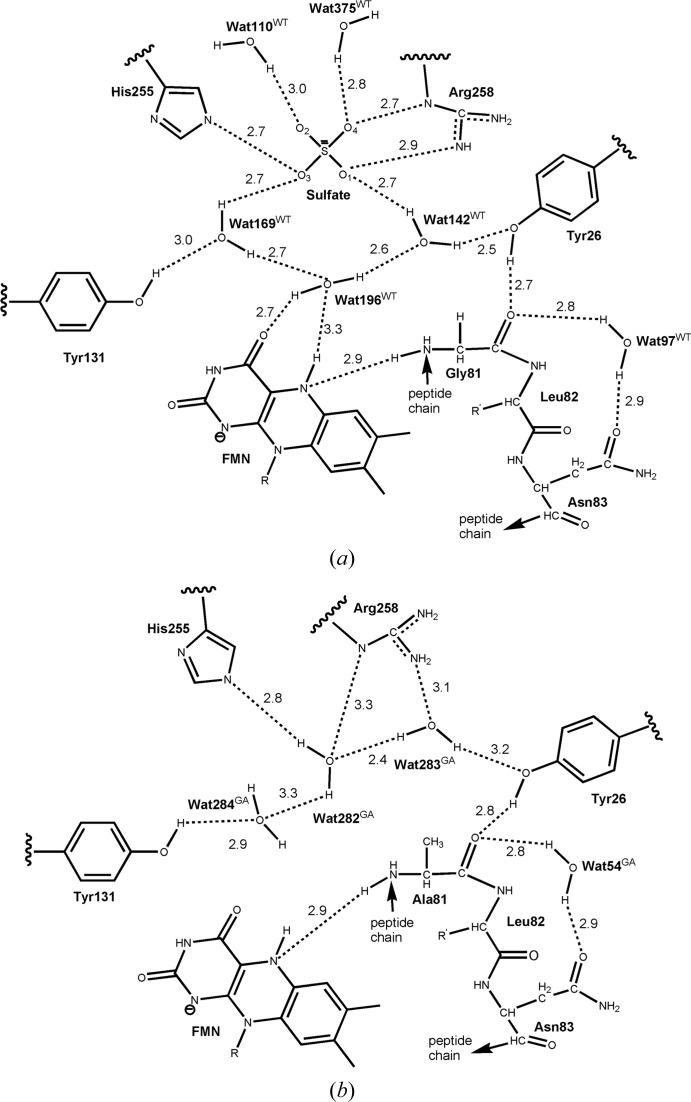

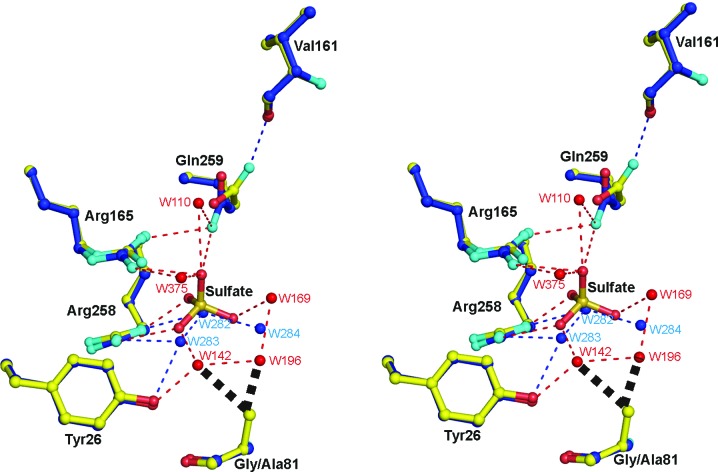

The ligand-free G81A mutant protein most closely resembles the reduced MDH-GOX2 structure. Nearly all of the well ordered side chains are in the same orientation and most of the interior water molecules are also retained. The sulfate anion and one water molecule (Wat169WT)1 of wild-type reduced MDH-GOX2 (Fig. 5 ▶ a) are replaced in G81A by three water molecules (Wat282GA, Wat283GA and Wat284GA; Fig. 5 ▶ b), while two water molecules from reduced MDH-GOX2 (Wat142WT and Wat196WT) are displaced in G81A by the Cβ atom of Ala81 (Figs. 5 ▶ and 6 ▶). These replacements are equivalent to a diplacement of the sulfate anion by water molecules, which are in turn displaced by the methyl group of the mutated Ala81 residue. The three new waters (Wat284GA, Wat282GA and Wat283GA) form a network that connects the side chains of Tyr131, His255, Arg258 and Tyr26 (Fig. 5 ▶ b). However, this water network does not interact directly with the flavin ring, but is located ∼3.5 Å above it. Wat110WT, which interacts with the sulfate, is retained but forms no additional hydrogen bonds within the active site. In contrast, Wat375WT, which forms hydrogen bonds to a sulfate oxygen, is absent in G81A (Fig. 5 ▶). However, Wat97WT, which bridges Gly/Ala81 O and Gln83 Nδ2, is retained (as Wat54GA) in the G81A mutant protein.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of water arrangements in the active sites of the reduced native and G81A mutant form of MDH-GOX2. Hydrogen-bonding distances are in Å. (a) Native reduced enzyme. The network of three water molecules (Wat169WT, Wat196WT, Wat142WT) and one sulfate ion are shown along with their interactions with each other, with nearby side chains and with two other waters, Wat110WT and Wat375WT. (b) G81A mutant enzyme. The three waters (Wat282GA, Wat283GA and Wat284GA) displace the native sulfate ion and three-water network and take up new positions. Wat54GA is in the same position as Wat97WT of the native enzyme. R is a ribityl phosphate group and R′ is a Leu side chain.

Figure 6.

Superposition of the active-site structures of the G81A mutant form of MDH-GOX2 (blue C atoms) and the mandelate-reduced MDH-GOX2 (yellow C atoms), including a bound sulfate anion in the latter, with their respective water molecules in blue and red. O and N atoms are shown in red and cyan, respectively, for both structures. Hydrogen bonds are shown as narrow dashed lines in blue for reduced MDH-GOX2 and in red for the G81A mutant proteins. The various residues are labeled in black. Side-chain atoms only are shown for each of the residues, except for Val161 and Gly/Ala81 for which main-chain atoms are also shown; the flavin and residues Tyr131 and His255 are omitted for clarity. The bold black dashed lines near the methyl group of Ala81 of G81A indicate steric repulsion of two water mocules of reduced MDH-GOX2 that are displaced by the methyl group in G81A. This diagram was prepared using PyMOL (DeLano, 2002 ▶).

The side chain of Gln259 is also oriented differently in G81A by a rotation of ∼30° about the Cβ—Cγ bond and a 180° flip about the Cγ—Cδ bonds, thereby interchanging the O∊1/N∊2 atoms (Fig. 6 ▶). This change in orientation results in the replacement of a hydrogen bond from the side-chain N atom to the sulfate anion by a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl O atom of Val161.

When G81A is compared with oxidized MDH-GOX2 the structures are also very similar, except that in the oxidized native enzyme the side chain of Tyr26 is rotated by about 13° about its Cα—Cβ bond compared with the reduced and G81A enzyme (Sukumar et al., 2004 ▶) and there is an additional water molecule bridging Tyr26 Oη and Leu82 O that is absent in the other two structures.

3.3. Complex formation of the G81A mutant protein with the poor substrates 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate and 2-hydroxyoctanoate

The indole- and octanoate-soaked crystals appeared to be bleached prior to and during data collection, although the extent of bleaching was difficult to quantify visually. In a separate experiment, microspectrophotometric measurements were carried out on crystals of similar size and under similar substrate-soaking conditions to those used for data collection. In both cases the crystals became fully bleached within several minutes (Fig. 4 ▶) and remained so for the duration of the experiments.

The ligands bound to the G81A mutant form of MDH-GOX2 were initially modeled as the hydroxy acids bound to the reduced enzyme rather than the keto acid since the latter forms are known to bind poorly to the reduced enzyme (Sukumar et al., 2004 ▶). However, the refined structures are probably not of sufficiently high resolution to rule out either of them binding in the keto-acid forms. To confirm this, ten cycles of refinement with REFMAC5 were carried out for both structures in which the ligands were restrained to be in the hydroxy or keto forms, i.e. with the C2 atom in a tetrahedral or trigonal configuration. In neither case did the resulting (2F o − F c) or (F o − F c) difference maps favor one model over the other. It is also possible that the crystals contain a mixture of oxidized and reduced enzymes bound to substrate and product, respectively.

2-Hydroxy-3-indolelactate and 2-hydroxyoctanoate both bind to G81A by displacing water molecules present at the active site of the G81A mutant form of MDH-GOX2. In the indole complex one water molecule of G81A (Wat284GA) is displaced, while in the octanoate complex two additional water molecules of G81A (Wat282GA and Wat283GA) are displaced from the active site (Fig. 5 ▶ b) plus two more waters, each of which are conserved in the oxidized and reduced native MDH-GOX2 structures. The orientation of the side chain of Gln259 and the ring of Tyr26 in both complexes is the same as in the G81A mutant protein.

2-Hydroxy-3-indolelactate binds to the G81A mutant enzyme in a significantly different orientation than 2-hydroxyoctanoate (Fig. 7 ▶). The B factors of individual atoms in 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate lie in the range 38–42 Å2, while in 2-hydroxyoctanoate the B factors range from 65 to 79 Å2, indicating that the octanoate molecule is poorly ordered in the structure.

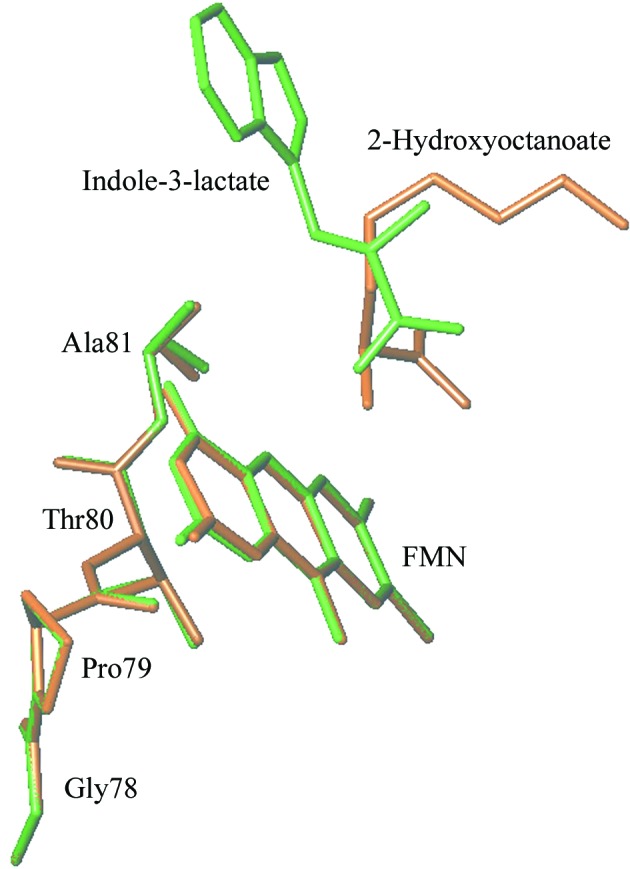

Figure 7.

Stick diagram of the substrates 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate (green) and 2-hydroxyoctanoate (brown) showing their relative orientations with respect to the flavin. This diagram was prepared using TURBO-FRODO (Roussel & Cambillau, 1989 ▶).

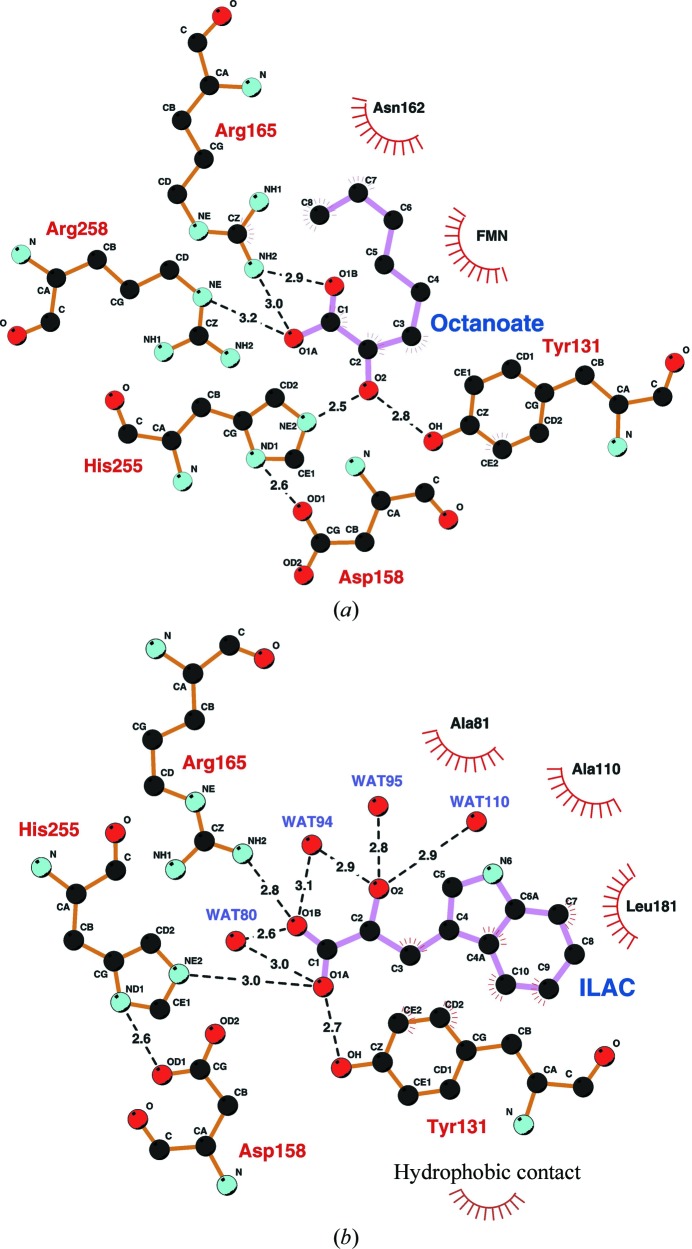

3.4. Enzyme–substrate interactions

In the octanoate complex, the carboxylate O atoms O1A and O1B each form hydrogen bonds to Arg165 Nη2 (3.0 and 2.9 Å, respectively), while oxygen O1A also forms a hydrogen bond to Arg258 N∊ (3.2 Å) (Fig. 8 ▶ a). The O2 hydroxyl of octanoate forms hydrogen bonds to both His255 N∊2 (2.5 Å) and Tyr131 Oη (2.8 Å). The O atom also lies close to N5 of FMN (3.1 Å), but the angular orientation of the C2—O2 bond with respect to the flavin N5 position and the plane of the flavin ring precludes hydrogen-bond formation. The hydrocarbon tail of 2-hydroxyoctanoate extends away from the flavin ring into a small hydrophobic pocket formed by the main-chain atoms of Val161–Gly163 and is in van der Waals contact with Asn162. Thus, residues Tyr131, Arg165 and Arg258 hold the substrate 2-hydroxyoctanoate in a favorable orientation for catalysis at the active site by forming hydrogen bonds to its carboxylate and hydroxyl groups. In this way, its interactions with FMN and with His255 are optimized for substrate oxidation to occur during the catalytic reaction.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the active-site structures of the 2-hydroxyoctanoate and 3-indolelactate complexes of the G81A mutant form of MDH-GOX2. Hydrogen-bonding interactions between the carboxylate and hydroxyl O atoms and nearby side chains or water molecules are shown as dashed lines and the distances are in Å. Residues making hydrophobic contact to the ligand are indicated as shown at the bottom right. C atoms are black, O atoms red and N atoms cyan. Covalent bonds within the ligand are drawn with pink lines, while those within the protein are drawn with orange lines. (a) The 2-hydroxyoctanoate–G81A complex. The ligand is labeled ‘Octanoate’. (b) The (d,l)-2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate–G81A complex. The ligand is labeled ‘ILAC’. This diagram was prepared using the program LIGPLOT (Wallace et al., 1995 ▶).

In the case of the indole complex, the carboxylate O atom O1A at C1 forms hydrogen bonds to the active-site residues Tyr131 Oη (2.7 Å) and His255 N∊2 (3.0 Å) and oxygen O1B is hydrogen bonded to Arg165 Nη2 (2.8 Å) (Fig. 8 ▶ b). However, the oxygen O2 at C2 of 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate only forms hydrogen bonds to water molecules. Moreover, C2 is 5.2 Å from N5 of FMN and 5.1 Å from His255 N∊2. These values suggest that 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate is not in a favorable configuration to carry out the reaction and may represent an unproductive dead-end complex. Unlike in the case of the octanoate complex, the side chain of Arg165 forms a hydrogen bond to only one of the carboxyl O atoms of the 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate molecule. The indole ring points away from the flavin ring, but in a different direction from the hydrophobic tail of 2-hydroxyoctanoate. It is in van der Waals contact with the hydrophobic side chains of Ala81, Ala110 and Leu181 (Fig. 8 ▶ b). Slightly farther away are the hydrophobic side chains of Ile133, Phe184 and Met208, which also appear to help stabilize binding.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Gly81Ala mutation on sulfate binding

The overall result of mutating Gly81 to Ala is to eliminate the binding of a network of three water molecules and a sulfate anion from the active site and to replace it with a new network of three water molecules. In addition, a glutamine side chain that interacted with the sulfate anion is reoriented to form a new hydrogen-bonding interaction within the protein. The G81A mutant protein has a midpoint potential associated with the FMNox/FMNsq redox couple that is 30 mV more negative than that of wild-type MDH or MDH-GOX2 (Dewanti et al., 2004 ▶). In other words, the small change of introducing an additional methyl group in the side chain at position 81 reduces the electrophilicity of FMN in G81A compared with MDH-GOX2. The lack of sulfate binding in the G81A structure may be a consequence of this lowered electrophilicity, as is the lowered catalytic rate of substrate oxidation relative to the wild-type enzyme (Table 1 ▶). The structure of G81A provides an explanation for the lower electrophilicity of FMN. A direct result of the Gly81Ala mutation is the displacement of two of the four water molecules, Wat142WT and Wat196WT, since the β-methyl group of Ala81 would occlude the binding of these waters (Fig. 6 ▶). The absence of these two waters and the presence of the extra methyl group in G81A lead to a lowered solvation around N5 of the FMN, thereby disturbing the hydrogen-bonding network and consequently reducing the polarity of the environment. The crystallization procedure used for G81A is identical to that used for native MDH-GOX2 (i.e. in the presence of 58 mM ammonium sulfate) and the holding solution for the crystals differed only slightly between them (58 mM versus 77 mM ammonium sulfate). However, the reduced native MDH-GOX2 crystal was prepared by reaction with 50 mM mandelate, a rapidly reacting but natural substrate of the native enzyme, immediately prior to cryogenic data collection, yet was found to contain sulfate in the active site (Sukumar et al., 2004 ▶). This suggested that the weakly bound product benzoylformate had been displaced by sulfate prior to freezing.

The G81A structure, with water replacing the sulfate anion found in MDH-GOX2, may more closely represent the native structure in vivo since the intracellular sulfate concentration is probably much lower than the 58 mM value used in crystallization. The two water molecules displaced by the methyl C atom of Ala81 (Wat142WT and Wat196WT) could be retained in the wild-type ligand-free enzyme, with additional waters replacing the sulfate anion. The side chain of Gln259 that interacts with the sulfate anion and the side chain of Arg165 in native MDH-GOX2 could be oriented as in G81A, where it forms a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl O atom of Asp158. The volume occupied by sulfate in MDH-GOX2 could then be filled with three or four water molecules, as in G81A. Thus, the water networks observed in the oxidized and reduced MDH-GOX2 structures linking Tyr26 to Tyr131 via the flavin ring and the water switch observed upon flavin reduction (Sukumar et al., 2004 ▶) could be maintained in the sulfate-free molecule.

4.2. Non-equivalent substrate binding in G81A

In addition to the substrate complexes of G81A reported here, several substrate or product complexes of FCB2 and its mutant forms have been reported. These include the wild-type FCB2–pyruvate complex (Xia & Mathews, 1990 ▶), complexes of pyruvate and/or phenylpyruvate with the Y143F mutant protein (Tegoni et al., 1995 ▶) and the complex of phenylglyoxylate with the L230A mutant form of FCB2 (Mowat et al., 2004 ▶). In most of these complexes the ligand binds in a ‘productive’ mode in which both carboxylate O atoms of the ligand interact with one or both active-site arginine side chains and possibly with a nearby tyrosine side chain and the C2 oxygen can form a hydrogen bond to the active-site histidine and/or tyrosine side chain, as exemplified by the octanoate complex of G81A. This ‘productive’ mode of binding is compatible with mechanisms for the reductive half-reaction which are facilitated by the strictly conserved and essential active-site histidine (Lederer, 1991 ▶; Dewanti & Mitra, 2003 ▶; Mowat et al., 2004 ▶). However, in two cases, a phenylpyruvate and a pyruvate complex of the Y143F FCB2 mutant protein, the ligand is bound in a ‘nonproductive’ mode with the carboxylate interacting with the active-site histidine and tyrosine side chains (equivalent to His255 and Tyr131 in MDH-GOX2). The observed binding of 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate to G81A is similar to the ‘nonproductive’ mode found in the Y143F mutant form of the FCB2–phenylpyruvate structure. In both cases one carboxylate O atom is hydrogen bonded to His255 and Tyr131 or their equivalents and the other is hydrogen bonded to an active-site arginine, Arg165 in the case of G81A and the equivalent of Arg258 in the FCB2 mutant protein. Since 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate and phenylpyruvate are poor substrates for the respective enzymes, the observed ‘nonproductive’ binding mode is likely to represent a dead-end complex. The slower rate of reduction of crystals of the G81A mutant form of MDH observed for 2-hydroxy-3-indolactate than for 2-hydroxyoctanoate (Fig. 4 ▶), a reversal of the relative rates of reduction by these two substrates of the mutant enzyme in solution (Table 1 ▶), may result from a need for the 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate molecule to reorient itself in the active site after binding.

5. Conclusions

Unlike the ‘wild-type’ MDH-GOX2 enzyme, either in its oxidized or reduced states, the G81A mutant protein does not contain a sulfate anion bound in the active site, but instead a hydrogen-bonded network of three water molecules. Two other water molecules observed in both the oxidized and reduced MDH-GOX2 active sites are displaced by the methyl-group side chain of substituted Ala81. The displacement of these two water molecules near the flavin may reduce the polarity of its environment by disruption of the hydrogen-bonding network and thereby reduce the electrophilicity of the flavin ring. The reduced electrophilicity may account for the 30 mV lowering of the flavin redox potential and the resultant 10–100-fold lowered rates of substrate oxidation exhibited by the G81A mutant protein.

The lowered catalytic activity of the G81A mutant enzyme and the use of the poor substrates 2-hydroxyoctanoate and 2-hydroxy-3-indolelactate have enabled the binding of these ligands in the active site to be observed in the crystalline state, whereas previous attempts with the ‘wild-type’ MDH-GOX2 enzyme were unsuccessful. The octanoate ligand appears to bind in an enzymatically productive mode, with its carboxylate group forming hydrogen bonds to two arginine side chains and the C2 O atom interacting with a histidine and a tyrosine side chain, both being potential active-site bases. Its slow turnover in the wild-type enzyme (Table 1 ▶) may reflect its non-optimal binding relative to mandelate, the natural substrate. The indolelactate ligand, on the other hand, appears to bind in an unproductive mode with its carboxylate group interacting with the histidine and tyrosine side chains as well as one of the two arginine side chains, while the C2 O atom is surrounded by a cluster of water molecules and is more than 5 Å from any potential active-site bases. This unproductive binding mode has been observed previously in a mutant form of the homologous enzyme FCB2 in complex with pyruvate and phenylpyruvate.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: G81A MDH-GOX2, ligand-free, 3giy, r3giysf

PDB reference: indolelactate complex, 2a7p, r2a7psf

PDB reference: octanoate complex, 2a85, r2a85sf

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr Florence Lederer for useful comments and Dr Zhi-wei Chen for computational assistance. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. Use of the BioCARS Sector 14 was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources under grant No. RR-07707. Use of the NE-CAT 8BM beamline and this work were supported by award RR-15301 from the NCRR at the National Institutes of Health. Microspectrophotometric studies were supported by MIUR, Italy, grant No. 20074TJ3ZB_004.

Footnotes

The superscripts GA and WT refer to water molecules observed in the G81A mutant protein structure and the native MDH-GOX2 structure, respectively.

References

- Blobel, G. (1980). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 77, 1496–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brünger, A. T. (1992). Nature (London), 355, 472–475. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brünger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J.-S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N. S., Read, R. J., Rice, L. M., Simonson, T. & Warren, G. L. (1998). Acta Cryst. D54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994). Acta Cryst. D50, 760–763.

- Daff, S., Manson, F. D., Reid, G. A. & Chapman, S. K. (1994). Biochem. J. 301, 829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W. L. (2002). The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, California, USA.

- Dewanti, A. R. & Mitra, B. (2003). Biochemistry, 42, 12893–12901. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dewanti, A. R., Xu, Y. & Mitra, B. (2004). Biochemistry, 43, 10692–10700. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ghisla, S. & Massey, V. (1989). Eur. J. Biochem. 181, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hodel, A., Kim, S.-H. & Brünger, A. T. (1992). Acta Cryst. A48, 851–858.

- Le, K. H. D. & Lederer, F. (1991). J. Biol. Chem. 266, 20877–20881. [PubMed]

- Lederer, F. (1991). Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Flavoenzymes, edited by F. Muller, Vol. 2, pp. 153–242. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Lehoux, I. E. & Mitra, B. (1999). Biochemistry, 38, 9948–9955. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lehoux, I. E. & Mitra, B. (2000). Biochemistry, 39, 10055–10065. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lindqvist, Y. (1989). J. Mol. Biol. 209, 151–166. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lindqvist, Y., Brändén, C.-I., Mathews, F. S. & Lederer, F. (1991). J. Biol. Chem. 266, 3198–3207. [PubMed]

- Maeda-Yorita, K., Aki, K., Sagai, H., Misaki, H. & Massey, V. (1995). Biochimie, 77, 631–642. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Merli, A., Brodersen, D. E., Morini, B., Chen, Z., Durley, R. C., Mathews, F. S., Davidson, V. L. & Rossi, G. L. (1996). J. Biol. Chem. 271, 9177–9180. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mitra, B., Gerlt, J. A., Babbitt, P. C., Koo, C. W., Kenyon, G. L., Joseph, D. & Petsko, G. A. (1993). Biochemistry, 32, 12959–12967. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morris, A. L., MacArthur, M. W., Hutchinson, E. G. & Thornton, J. M. (1992). Proteins, 12, 345–364. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mowat, C. G., Wehenkel, A., Green, A. J., Walkinshaw, M. D., Reid, G. A. & Chapman, S. K. (2004). Biochemistry, 43, 9519–9526. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. (1997). Acta Cryst. D53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rivetti, C., Mozzarelli, A., Rossi, G. L., Henry, E. R. & Eaton, W. A. (1993). Biochemistry, 32, 2888–2906. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Roussel, A. & Cambillau, C. (1989). Silicon Graphics Geometry Partners Directory, pp. 77–78. Silicon Graphics, Mountain View, California USA.

- Sukumar, N., Dewanti, A. R., Mitra, B. & Mathews, F. S. (2004). J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3749–3757. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sukumar, N., Xu, Y., Gatti, D. L., Mitra, B. & Mathews, F. S. (2001). Biochemistry, 40, 9870–9878. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sun, W., Williams, C. H. Jr & Massey, V. (1997). J. Biol. Chem. 272, 27065–27076. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tegoni, M., Begotti, S. & Cambillau, C. (1995). Biochemistry, 34, 9840–9850. [PubMed]

- Wallace, A. C., Laskowski, R. A. & Thornton, J. M. (1995). Protein Eng. 8, 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z.-X. & Mathews, F. S. (1990). J. Mol. Biol. 212, 837–863. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y., Dewanti, A. R. & Mitra, B. (2002). Biochemistry, 41, 12313–12319. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y. & Mitra, B. (1999a). Biochemistry, 38, 12367–12376. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y. & Mitra, B. (1999b). In Flavins and Flavoproteins 1999, edited by S. Ghisla, P. Kroneck, P. Macheroux & H. Sund. Berlin: Agency for Scientific Publications.

- Yeates, T. O. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 344–358. [PubMed]

- Yorita, K., Aki, K., Ohkuma-Soyejima, T., Kokubo, T., Misaki, H. & Massey, V. (1996). J. Biol. Chem. 271, 28300–28305. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: G81A MDH-GOX2, ligand-free, 3giy, r3giysf

PDB reference: indolelactate complex, 2a7p, r2a7psf

PDB reference: octanoate complex, 2a85, r2a85sf