Initially described in 1982, the persistent polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (PPBL) is characterized by a chronic, stable, persistent and polyclonal lymphocytosis, the presence of binucleated lymphocytes in the peripheral blood and a polyclonal increase in serum immunoglobulin-M (IgM) (1). In this apparently benign entity, we showed that PPBL was associated with recurrent chromosomal abnormalities and a typical cytogenetic profile including isochromosome 3q, +i(3q), premature chromosome condensation (PCC), both abnormalities in the same patient or chromosomal instability (2). Despite clinical and polyclonal lymphocytosis stability, the long-term follow-up is not yet well established.

We analyse and report here the long-term follow-up of 111 patients with typical PPBL. PPBL was diagnosed in 91 women (82%) (median age 40 years, range 19–66 years) and 20 men (median age 40.9 years, range 28–57 years). The patients, smokers in 98% of cases, were either asymptomatic or had minor and nonspecific complaints, such as fatigue. Physical examination was usually within normal limits, except for a mild splenomegaly present in 10% of cases. PPBL was diagnosed when blood smear analysis revealed the presence of a variable number of binucleated lymphocytes, whatever the lymphocyte count. At the time of diagnosis, 83% of patients presented with mild lymphocytosis and 17% with a lymphocyte count below 4 × 109/l. The median lymphocyte count was 5.45 × 109/l, with a range of 2.45–20.52 × 109/l. In all cases peripheral blood examination showed typical binucleated lymphocytes which were present with a variable percentage (median 4%, range 1–40%). Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed a polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis in all cases, with an expansion of the B CD19-positive and CD5-negative lymphocytes pool. Both kappa and lambda light chain were expressed in all cases, confirming the B-cell polyclonal expansion. The median of polyclonal serum IgM level was 6.0 g/l (normal: 0.5–2.7 g/l), with a range of 1.2–17.3 g/l. Ninety-eight patients underwent conventional cytogenetic analysis (CCA). Isochromosome +i(3q) was present in 34% (33 of 98 patients), PCC in 8% (8 of 98 patients) and both abnormalities in 31% (30 of 98 patients). CCA showed neither +i(3q) nor PCC in 28% (27 of 98 patients). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed in 84 cases. Isochromosome +i(3q) was studied in interphase with alpha-satellite chromosome 3-specific (SO CEP3) and LSI 3′BCL6 (3q27) break-apart probes obtained from Abott Molecular (Rungis, France). Isochromosome +i(3q) was detected in 71% (60 of 84 patients). We also combined CCA and FISH in 84 patients: after FISH, +i(3q) was detected in 17 patients with negative CCA and was confirmed in 43 patients with positive CCA. CCA and FISH were both negative in 24 cases.

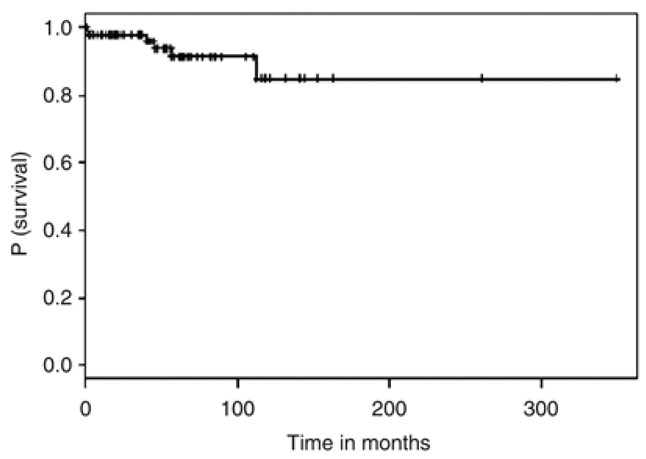

After a median follow-up of 4.4 years (0.5–29 years) (Figure 1), PPBL patients presented a stable clinical and biological course in 99 of 111 cases (89%). In two patients, we noticed a decrease of lymphocytosis and the number of binucleated lymphocytes but isochromosome +i(3q) persisted 2 years after stopping tobacco use (2). In our series, six patients died: one heavy smoker patient from pulmonary cancer nine years after PPBL diagnosis, 1 from myocardial infarction, 1 from cerebral aneurysm rupture, 2 deaths from unknown cause and 1 from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma described below. Two patients had IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) at the time of PPBL diagnosis. Two other patients developed IgM MGUS (serum IgM, 6.9 g/l and 12.88 g/l), 12 and 22 years after PPBL diagnosis, respectively. In these four cases, no bone marrow biopsy was performed. IgM gammopathy remained asymptomatic and stable after a median follow up of 102 months (range 52–348). Two patients presented pulmonary cancer in the clinical course of PPBL and one patient developed cervical cancer 12 years after diagnosis of PPBL. A malignant non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was also observed in three additional patients: two patients presented with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and one patient with a splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL).

Figure 1.

Event-free survival of 111 patients with PPBL

Among the three patients, the first case was a 34-year-old woman, smoker, with typical PPBL presenting at diagnosis with a mild absolute lymphocytosis (6.6 × 109/l) with 3% binucleated lymphoid cells. Peripheral blood flow cytometry analysis showed a polyclonal (kappa/lambda ratio: 2.7) lymphocytosis with predominant B CD19+ lymphocytes (59%). Supernumerary isochromosome +i(3q) without PCC was identified both by CCA and FISH; chromosomal instability was also present. Three years after PPBL diagnosis, the patient developed axillary lymphadenopathy. Histological examination showed DLBCL. Peripheral blood flow cytometry displayed a monoclonal B cell proliferation with 64% CD19+, kappa+, CD5− and CD10− lymphoid cells. CCA of the lymph node showed a complex karyotype: 42–44, XX, der(2) t(2;?)(q37;?), del(6)(p23), add(7)(p22), add(12)(p13), −13, −15, −16, −17, add(22)(p11), +mar1, +mar2 [cp 11]/46, XX [9]) without isochromosome +i(3q). Absence of +i(3q) was confirmed by FISH. The patient developed DLBCL in leukemic phase 3 years after PPBL diagnosis and despite three cycles of ACBVP regimen (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, bleomycin, vindesine and prednisone), then second-line chemotherapy, the patient died from progressive disease, 18 months after DLBCL diagnosis.

The second case was a 36-year-old man, smoker, who presented with a moderate splenomegaly and a mild lymphocytosis (8 × 109/l) with 4% binucleated lymphocytes at diagnosis. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed a B-cell polyclonal proliferation. Supernumerary isochromosome 3q, +i(3q) was detected after CCA and FISH studies. Chromosomal instability was present but not PCC. He received chlorambucil during 6 months with decrease of splenomegaly and total disappearance of binucleated lymphocytes. However, the beneficial effects of chemotherapy were of short duration, as splenomegaly and binucleated lymphocytes reappeared 2 months after stopping chlorambucil. Nine years after PPBL diagnosis, the patient presented with multiple superficial lymph nodes, and histological examination showed DLBCL with B-lymphocytes that expressed CD20+, bcl-2+/−, bcl-6+/−, MUM1+/−, IgD+ without CD5 and CD10. Unfortunately, neither peripheral blood flow cytometry analysis nor CCA was performed at the time of DLBCL diagnosis. He received four cycles of R-ACBVP (rituximab and ACBVP) followed by methotrexate, etoposide and cytarabine. The patient remains in persistent complete remission 2 years after DLBCL diagnosis and lymphocytosis is still absent.

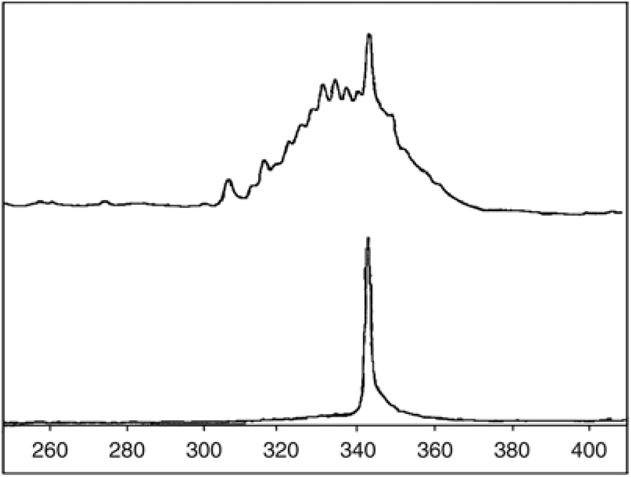

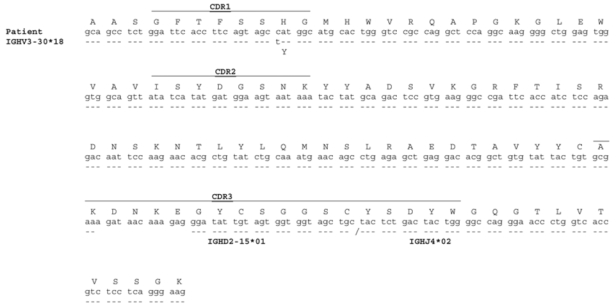

The third case was a 63-year-old woman, smoker, who was diagnosed with PPBL, with 3.8 × 109/l lymphocytes and 2% binucleated lymphocytes. Flow cytometry analysis showed a B-cell polyclonal proliferation with 68% CD19-positive lymphoid B cells. The patient had no splenomegaly and no lymph nodes. Supernumerary isochromosome +i(3q) was detected both on CCA and FISH. Moreover, CCA also identified combined trisomy 3 and +i(3q). Chromosomal instability and PCC were also observed. There was an increase in serum polyclonal IgM (16.7 g/l). During 3 years, three repeated CCAs detected again +i(3q) and trisomy 3 on each peripheral blood specimen. During the same period, a large splenomegaly appeared and lymphocyte count increased to 30 × 109/l. The follow-up of peripheral blood flow cytometry showed a progressive increase of the lambda/kappa ratio from 1–4 with appearance of a monoclonal CD19+, CD5− and CD10− B-cell proliferation. Blood smear analysis did not reveal any binucleated lymphocytes nor villous lymphocytes. Agarose gel serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation detected a lambda monoclonal pattern for IgM (18.6 g/l). CCA showed again an isochromosome +i(3q) but without +3. The presence of splenomegaly and the CD5− CD10− monoclonal B cell proliferation led us to regard the diagnosis of SMZL. The patient received four cycles of rituximab, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide and is alive 18 months after chemotherapy with no lymphocytosis (0.6 × 109/l) and no detectable binucleated lymphocytes. In this case, DNA was available from both the lymphoma and PPBL samples at the time of diagnosis, and was evaluated for clonality analysis. As expected, amplification of immunoglobulin heavy-chain (IGH) gene rearrangements showed a clear monoclonal band in the lymphoma sample. The lymphoma B cells expressed functional IgHV3-30, with greater (99.6%) than 98% nucleic acid sequence homology to the germ line IgHV3-30. The IgHJ segment used by that case was IGHJ4 and the IGHD segment was IGHDH2-5. We also detected a minor clone having an identical IGH rearrangement (Figures 2 and 3) and sequences at PPBL and SMZL. Dilution experiments indicated that this clone represented approximatively 1% of a monoclonal cell line mixed in polyclonal peripheral blood lymphocytes.

Figure 2.

Analysis of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) gene rearrangements in PPBL and lymphoma samples. Amplification of IGH gene rearrangements was performed using Biomed-2 PCR protocols (11) with primers specific for the framework region 1. Fluorescent PCR products were then analyzed by GeneScanning. The monoclonal rearrangement of the lymphoma sample (bottom) appears as a unique 341 base-pair pick. A band of similar size can be seen among polyclonal rearrangements in the initial PPBL sample (top).

Figure 3.

Nucleotide and amino-acid sequences of the patient’s lymphoma IgH rearrangement. Comparison is made with the closest germline genes. A dash indicates an identity. CDR, complementary-determining region.

Persistent polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis is a rare disorder. We report the follow-up and event-free survival (Figure 1) of a cohort of 111 patients. The stability of lymphocyte count over time and the usually indolent clinical course suggest that PPBL remains in most cases a benign disorder. In our study, 89% of patients remain free of symptoms or complications after a median follow-up of 53 months. In the literature, there are reports of only a few PPBL patients who developed cancers, either solid tumours (3) or hematologic malignancies (4). We report three additional patients developing non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas after PPBL diagnosis, two patients with DLBCL and one with SMZL. In two of the three cases, we were not able to demonstrate a direct relationship between the occurrence of PPBL and lymphoma, particularly +i(3q) at the time of PPBL and malignant lymphoma’s diagnosis. We performed clonality analysis in one of the three patients developing SMZL. As expected, the clonality analysis revealed the presence and the evolution of the same clonal population at the time of PPBL and lymphoma’s diagnosis, suggesting possible evolution of a preexistent monoclonal subpopulation in PPBL toward a malignant monoclonal population. A clonal disease was previously demonstrated in PPBL possibly increasing the risk of cancer in few cases (5,6). Interestingly, four patients presented at the time of diagnosis or developed IgM MGUS suggesting the possibility to change from PPBL to IgM MGUS and/or Waldenströms macroglobulinaemia. Moreover, we report also two cases of pulmonary cancer in two smokers and one case of cervical cancer. The etiology of PPBL remains unclear: the role of tobacco in the occurrence of these cancers is probably dominant. Intravascular B-cell infiltrates, constantly associated with Bcl-2 immunostaining as seen in some lymphomas, have been reported in PPBL patients (7). Moreover, multiple Bcl-2/IgH gene rearrangements, mostly polyclonal, but possibly leading to oligoclonal expansion, were observed contributing to the emergence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The genetic predisposition (8), the persistent viral infection, the chromosomal instability (9) or genetic alterations of ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated and Rad3-related gene leading to loss of cell differentiation and cell-cycle abnormalities (10) could explain the possibility of increase of the risk of cancer.

In conclusion, the possibility of PPBL to evolve toward a clonal proliferation, malignant lymphoma or secondary solid cancer led us to consider PPBL not as a benign pathology. We recommend a careful and continued clinical and biological long-term follow-up in all PPBL patients.

References

- 1.Gordon DS, Jones BM, Browing SW, Spira TJ, Laurence DN. Persistent polyclonal lymphocytosis of B-lymphocytes. New England Journal of Medicine. 1982;307:232–236. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207223070407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mossafa H, Malaure H, Maynadie M, Valensi F, Schillinger F, Garand R, et al. et le Groupe Française d’Hématologie Cellulaire (GFHC). Persistent polyclonal B lymphocytosis with binucleated lymphocytes: a study of 25 cases. British Journal of Haematology. 1999;104(3):486–493. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawlor E, Murray M, O’Brian DS, Blaney C, Foroni L, Sarsfield P, et al. Persistent polyclonal B lymphocytosis with Epstein-Barr virus antibodies and subsequent malignant pulmonary blastoma. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1991;44:341–342. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roy J, Ryckman C, Bernier V, Whittom R, Delage R. Large cell lymphoma complicating persistent polyclonal B cell lymphocytosis. Leukemia. 1998;12:1026–1030. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan MA, Benedict SH, Carstairs KC, Francombe WH, Gelfand EW. Expansion of B-lymphocytes with an unusual immunoglobulin rearrangment associated with atypical lymphocytosis and cigarette smoking. American Journal of Respiratory and Cellular Molecular Biology. 1990;2:549–552. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/2.6.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delage B, Darveau A, Jacques L, Huot A, Delage JM. Chronic B-cell lymphocytosis of the young woman: clinical, phenotypic, and molecular studies. Blood. 1992;80(suppl 1):447a. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feugier P, Kennel de March A, Lesesve JF, Monhoven N, Dorvaux V, Braun F, et al. Intravascular bone marrow accumulation in persistent polyclonal lymphocytosis: a misleading feature for B-cell neoplasm. Modern Pathology. 2004;17:1087–1096. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troussard X, Valensi F, Debert C, Maynadie M, Schillinger F, Bonnet P, et al. Polyclonal lymphocytosis with binucleated lymphocytes: a genetic predisposition. British Journal of Haematology. 1994;88:275–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb05018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mossafa H, Tapia S, Flandrin G, Troussard X the Groupe Français d’hématologie Cellulaire (GFHC) Chromosomal instability and ATR amplification gene in patients with persistent polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (PPBL) Leukemia Lymphoma. 2004;45:1401–1406. doi: 10.1080/10428194042000191738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith L, Liu SJ, Goodrich L, Jacobson D, Degnin C, Bentley N, et al. Duplication of ATR inhibits MyoD, induces aneuploidy and eliminates radiation-induced G1 arrest. Nature Genetics. 1998;19:39–46. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dongen JJ, Langerak AW, Brüggemann M, Evans PA, Hummel M, Lavender FL, et al. Design and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98-3936. Leukemia. 2003;17:2257–2317. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]