Abstract

The α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (enals) acrolein, crotonaldehyde, and trans-4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) are products of endogenous lipid peroxidation, arising as a consequence of oxidative stress. The addition of enals to dG involves Michael addition of the N2-amine to give N2-(3-oxopropyl)-dG adducts, followed by reversible cyclization of N1 with the aldehyde, yielding 1,N2-dG exocyclic products. The 1,N2-dG exocyclic adducts from acrolein, crotonaldehyde, and 4-HNE exist in human and rodent DNA. The enal-induced 1,N2-dG lesions are repaired by the nucleotide excision repair pathway in both Escherichia coli and mammalian cells. Oligodeoxynucleotides containing structurally defined 1,N2-dG adducts of acrolein, crotonaldehyde, and 4-HNE were synthesized via a postsynthetic modification strategy. Site-specific mutagenesis of enal adducts has been carried out in E. coli and various mammalian cells. In all cases, the predominant mutations observed are G→T transversions, but these adducts are not strongly miscoding. When placed into duplex DNA opposite dC, the 1,N2-dG exocyclic lesions undergo ring opening to the corresponding N2-(3-oxopropyl)-dG derivatives. Significantly, this places a reactive aldehyde in the minor groove of DNA, and the adducted base possesses a modestly perturbed Watson−Crick face. Replication bypass studies in vitro indicate that DNA synthesis past the ring-opened lesions can be catalyzed by pol η, pol ι, and pol κ. It also can be accomplished by a combination of Rev1 and pol ζ acting sequentially. However, efficient nucleotide insertion opposite the 1,N2-dG ring-closed adducts can be carried out only by pol ι and Rev1, two DNA polymerases that do not rely on the Watson−Crick pairing to recognize the template base. The N2-(3-oxopropyl)-dG adducts can undergo further chemistry, forming interstrand DNA cross-links in the 5′-CpG-3′ sequence, intrastrand DNA cross-links, or DNA−protein conjugates. NMR and mass spectrometric analyses indicate that the DNA interstand cross-links contain a mixture of carbinolamine and Schiff base, with the carbinolamine forms of the linkages predominating in duplex DNA. The reduced derivatives of the enal-mediated N2-dG:N2-dG interstrand cross-links can be processed in mammalian cells by a mechanism not requiring homologous recombination. Mutations are rarely generated during processing of these cross-links. In contrast, the reduced acrolein-mediated N2-dG peptide conjugates can be more mutagenic than the corresponding monoadduct. DNA polymerases of the DinB family, pol IV in E. coli and pol κ in human, are implicated in error-free bypass of model acrolein-mediated N2-dG secondary adducts, the interstrand cross-links, and the peptide conjugates.

1. Introduction

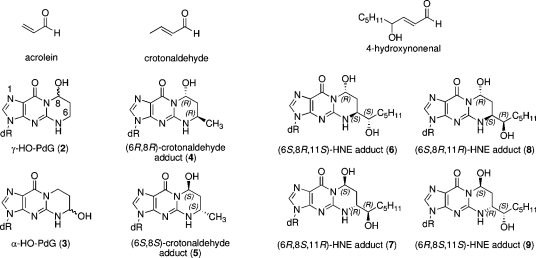

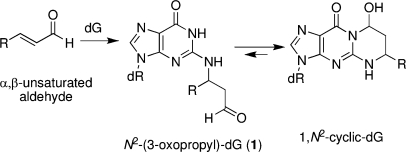

The α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (enals) acrolein, crotonaldehyde, and trans-4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE)1 (Figure 1) are products of endogenous lipid peroxidation, arising as a consequence of oxidative stress (1−5). Acrolein and crotonaldehyde are produced during the combustion of organic matter and exogenous exposure can occur from cigarette smoke and automobile exhaust (6−10). Sources, metabolism, and biomolecular interactions of acrolein have been reviewed (10). Enals react with DNA nucleobases to give exocyclic adducts; they also react with proteins (2,6). The addition of enals to dG involves Michael addition of the N2-amine to give N2-(3-oxopropyl)-dG adducts (1), followed by cyclization of N1 with the aldehyde (Scheme 1), yielding the corresponding cyclic 1,N2-dG products (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes acrolein, crotonaldehyde, and 4-HNE and their cyclic 1,N2-dG adducts.

Scheme 1. 1,N2-dG Cyclic Adducts Arising from Michael Addition of Enals to dG.

The principal acrolein adduct is 3-(2′-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-8-hydroxypyrimido[1,2-a]purin-10(3H)-one (γ-OH-PdG, 2) (Figure 1) (11−13), although the regioisomeric 3-(2′-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-6-hydroxypyrimido[1,2-a]purin-10(3H)-one (α-OH-PdG, 3) has also been observed (12−14). The γ-OH-PdG adduct 2 exists as a mixture of C8-OH epimers. Michael addition of the N2-atom of dG to higher enals, such as crotonaldehyde and 4-HNE, creates an additional stereocenter at C6 of the 1,N2-dG adduct. Four diastereomers are possible for the crotonaldehyde adducts; the two possessing the trans relative configurations at C6 and C8 (4 and 5) are the predominant species (12,15,16). An alternative pathway for the formation of the crotonaldehyde adducts involves the reaction of dG with two equivalents of acetaldehyde (17−20). The corresponding 4-HNE-derived 1,N2-dG adducts possess an additional stereocenter on the C6 side chain, resulting in four observable diastereomers (6−9). Acrolein adducts of other nucleosides have also been characterized (21,22).

The 1,N2-dG adducts of acrolein (2 and 3), crotonaldehyde (4 and 5), and 4-HNE (6−9) exist in human and rodent DNA (3−5,7,14,23−26). In human tissues, these lesions have been detected at levels ranging from 0.6 to 2000 adducts per 109 guanines (reviewed in ref (5)). Both regioisomers of the acrolein adduct have been detected in lung tissue of smokers (14). The binding pattern of acrolein−DNA adducts is similar to the p53 mutational pattern in human lung cancer, implicating acrolein as a possible major cigarette-related lung carcinogen (27). DNA from liver specimens from individuals suffering from Wilson’s disease and hemochromatosis contains mutations attributed to 1,N2-dG adducts of 4-HNE (28).

2. Syntheses of Oligodeoxynucleotides Containing Site-Specific 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts Derived from α,β-Unsaturated Aldehydes (Enals)

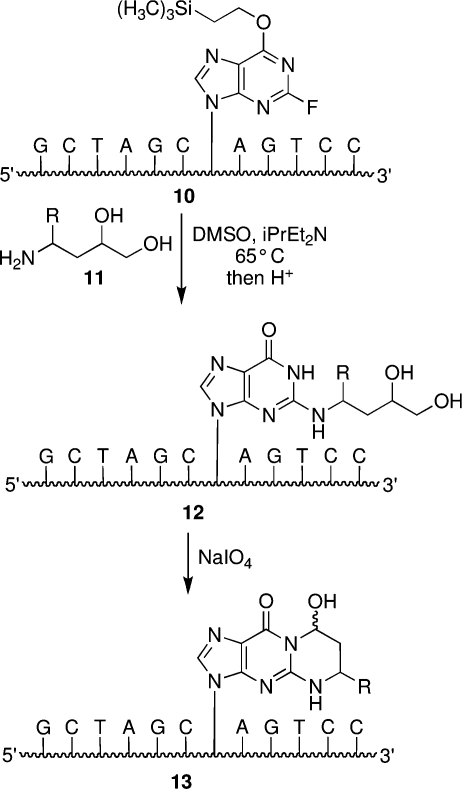

Aldehyde groups have been introduced into DNA through periodate cleavage of vicinal diols (29). Johnson’s lab, as well as ours, synthesized an oligodeoxynucleotide containing N2-(3,4-dihydroxybutyl)-dG 12 (R = H) in a sequence-specific manner, and this modified nucleobase was subsequently converted to the 1,N2-acrolein adduct 13 (R = H) via periodate oxidation (Scheme 2) (30). The N2-(3,4-dihydroxybutyl)-dG was introduced by different approaches. Whereas the Johnson lab used a suitably protected phosphoramidite reagent of N2-(3,4-dihydroxybutyl)-dG, we utilized a postsynthetic modification strategy in which oligodeoxynucleotides containing an O6-[(2-trimethylsilyl)ethyl]-2-fluorohypoxanthine 10 was reacted with 3,4-dihydroxybutylamine (11, R = H) via a nucleophilic aromatic displacement reaction (Scheme 2) (31,32). The postsynthetic modification strategy allowed for the preparation of oligodeoxynucleotides containing dG adducts of crotonaldehyde (33) and 4-HNE (34) from a single modified phosphoramidite reagent (31,32). The requisite amino diols 11 for the crotonaldehyde (R = CH3) and 4-HNE (R = CH(OH)C5H11) adducts were synthesized in enantiomerically pure form to obtain oligodeoxynucleotides containing stereochemically defined adducts (20,34−36). This strategy has been extended to the preparation of oligodeoxynucleotides containing malondialdehyde adducts of dG, 3-(2′-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)pyrimido[1,2-a]purin-10(3H)-one (M1dG), and dA (37−39). The postsynthetic modification strategy could not be applied to oligodeoxynucleotides containing α-OH-PdG adduct 3, which were prepared using the modified phosphoramidite approach (40,41).

Scheme 2. Site-Specific Synthesis of Oligodeoxynucleotides Containing 1,N2-dG Adducts of Acrolein, Crotonaldehyde, and 4-HNE by the Postsynthetic Modification Strategy.

3. Isomerization of Enal-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts to Aldehydes When Placed Opposite dC in Duplex DNA

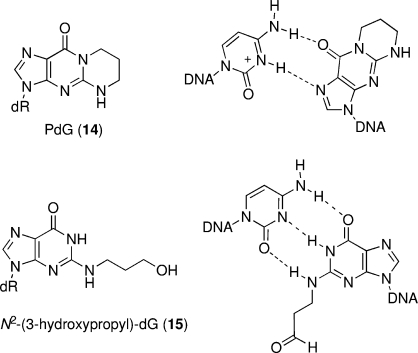

The formation of 1,N2-dG annelation products (2−9) blocks the Watson−Crick hydrogen-bonding face of the nucleobase, and these adducts were anticipated to be premutagenic lesions. Earlier studies had focused on the structural characterization of a model exocyclic adduct, 3-(2′-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydropyrimido[1,2-a]purin-10(3H)-one (PdG) 14 (Figure 2). NMR analyses revealed that in duplex DNA, PdG tended to adopt a syn orientation about the glycosyl bond and formed pairing interactions with the complementary dC via the Hoogsteen edge (42−44) (Figure 2). Recent NMR studies have indicated that the acrolein-derived α-OH-PdG adduct 3 also conserves the ring-closed form and adopts a syn conformation in duplex DNA (45). Although these structural features are similar to those previously determined for the model PdG adduct 14(42−44), the presence of the OH substituent in the former lesion results in a more stable positioning of the cyclic adduct in the major groove and a less perturbed DNA structure at the 3′-flanking base pair.

Figure 2.

Model substrates for the γ-HO-PdG adduct in DNA. Top left: PdG (14), a model for the ring-closed form of γ-HO-PdG (2). Top right: PdG forms a Hoogsteen pair with dC in duplex DNA. Bottom left: Reduced γ-HO-PdG adduct (15), a model for the ring-opened N2-(3-oxopropyl)-dG (1). Bottom right: N2-(3-oxopropyl)-dG (1) forms a Watson−Crick pair with dC in duplex DNA.

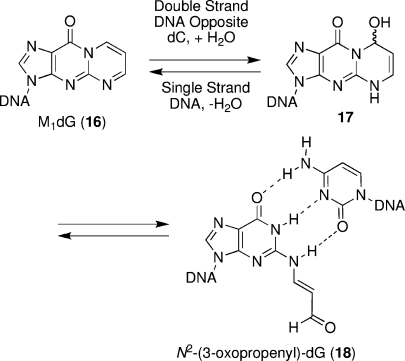

In contrast to the PdG adduct 14 and the α-OH-PdG adduct 3, the M1dG adduct 16 undergoes hydration at C8 and subsequent ring opening to a related aldehyde adduct, N2-(3-oxopropenyl)-dG (18), when placed opposite dC in DNA at neutral pH (Scheme 3) (46−48). NMR structural studies of the aldehyde 18 in duplex DNA revealed that its formation placed the N2-(3-oxopropenyl) group in the minor groove, with minimal DNA structural perturbation, allowing normal Watson−Crick base pairing (49,50). Under similar conditions in duplex DNA, 1,N2-dG enal adducts also undergo ring opening, placing the N2-(3-oxopropyl) group in the minor groove (51). This was first shown for the acrolein-derived γ-OH-PdG adduct 2(52). Structural analyses of the acrolein-derived adduct 2 revealed that the ring-opened aldehyde 1 enabled maintenance of Watson−Crick base pairing at the lesion site (Scheme 4, structures shown in box, R = H) (52). The similar chemistry (as compared to the M1dG lesion) was consistent with the fact that enal adducts are lower oxidation state homologues of 16. With the acrolein adduct 2, ring opening to the aldehyde is complete at neutral pH.

Scheme 3. Ring-Opening Chemistry of the M1dG Adduct Opposite dC in Duplex DNA.

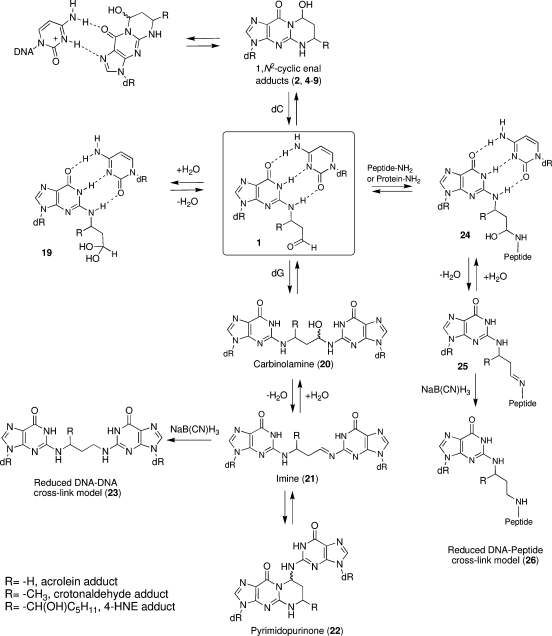

Scheme 4. Ring-Opening and Cross-Linking Chemistry of 1,N2-Enal-Derived dG Adducts Opposite dC in Duplex DNA.

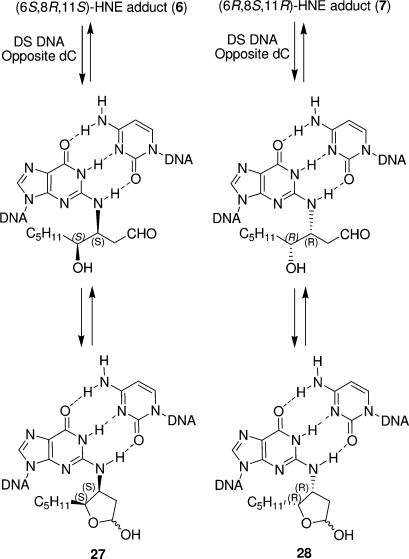

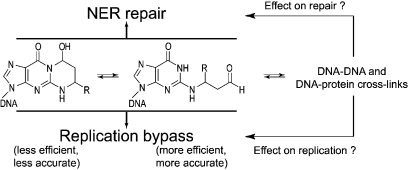

In contrast to the acrolein adduct 2, the diastereomeric crotonaldehyde adducts 4 and 5 only partially open to the respective aldehydes (35). With 4-HNE, the ring-opening chemistry is more complex (53,54). When placed complementary to dC in this duplex, the (6S,8R,11S)- and (6R,8S,11R)-HNE-dG adducts 6 and 7 open to the corresponding N2-dG aldehydic products. However, the hydroxyl group of the adduct side chain reacts with the aldehyde group to afford diastereomeric cyclic hemiacetals (27 and 28, Scheme 5). The open-chain aldehyde and hemiacetal forms exist in equilibrium with the latter being the predominant species. The trans-relative stereochemistry of the pentyl side chain and lactol hydroxyl groups is preferred (53). In all cases, the underlying significance related to the formation of minor groove aldehydes when placed opposite dC in duplex DNA is that these aldehydes represent reactive electrophiles that can undergo further chemistry, for example, formation of DNA−DNA cross-links or DNA−protein conjugation products (Scheme 4).

Scheme 5. (6S,8R,11S)- and (6R,8S,11R)-4-HNE-dG Adducts (6 and 7) Form Cyclic Hemiacetals after Initial Ring Opening Opposite dC in Duplex DNA.

4. Mutagenic Consequences of Enal-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts

4.1. Acrolein-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts

Acrolein is mutagenic in bacterial and mammalian cells (55,56), including human fibroblast cells (13,57,58), and is carcinogenic in rats (59). Kawanishi and co-workers examined types of mutations induced by acrolein in the supF gene of vector DNA replicated in normal human fibroblasts; the majority of mutations were base substitutions, predominantly in G:C pairs with a significant number of them being detected at two adjacent bases (58). Base substitutions in G:C pairs also predominated when acrolein-treated supF-containing vector was replicated in human lung fibroblasts; sequences with a run of dGs were the mutational hotspots (13). Importantly, relative mutagenicity of acrolein dG adducts, defined as mutant/DNA adduct, was significantly greater than that of UV-induced lesions. Using a similar approach, Kim and co-workers (60) did not observe a significant increase in mutation frequency in either DNA repair-proficient or nucleotide excision repair (NER)-deficient human fibroblasts. They also could not detect mutations in the target gene within genomic DNA of mouse fibroblasts that were exposed to acrolein, even though the induction of DNA damage was confirmed. Taken together, these data suggest that the mutagenic effect of acrolein adducts is manifested only when the extent of DNA damage is substantial; they also suggest that the propensity of acrolein adducts to induce mutations may be dependent upon variations in biological context, including specifics of a particular cellular genetic background and patterns of gene expression.

The mutagenic properties of acrolein-induced and related model adducts have also been investigated following replication of site specifically modified vector DNAs in Escherichia coli and various mammalian cell lines (Table 1). There are two common experimental strategies that are routinely used to assess the mutagenic properties of DNA adducts within site specifically modified vector DNAs. One strategy is to investigate mutagenic consequences following replication of a single-stranded DNA. Because DNA repair mechanisms utilize the complementary DNA sequences to restore DNA to its undamaged state, the possibility that the lesion will be removed prior to replication is precluded; thus, the major advantage of using a single-stranded vector is that the mutagenic potential of the lesion can be directly measured. An alternative approach is to insert the lesion into a double-stranded vector such that the damaged and nondamaged strands are marked by distinct sequence signatures. The advantage of this strategy is that contribution of DNA repair to cellular processing of the lesion can be assessed. Furthermore, both the extent of replication blockage caused by the lesion and the mutagenic outcome of this replication can be simultaneously evaluated, particularly by utilizing DNA repair-deficient cells.

Table 1. Mutagenic Properties of Enal-Derived and Related 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts: Effect of Biological Host, DNA Sequence Context, and Vector System.

| adduct | host | sequence context | vector | mutagenic outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | E. coli AB1157 | CpGpT | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 100% of G→T transversions in non-SOS-induced cells; 51% of G→T transversions, 17% of G→Α transitions, and <0.5% of G→C transversions in SOS-induced cells (61)a |

| 2 | 14 | E. coli JM105 | TpGpT | double-stranded | single base substitutions; no mutations in non-SOS-induced cells; 1% of G→T transversions and 1% of G→Α transitions in SOS-induced cells (62) |

| 3 | 14 | E. coli JM105 | (CpG)3b | double-stranded | frameshift mutations; 2.5%, 70% of which are CG deletions (63) |

| 4 | 14 | E. coli derivatives of AB1157 | (CpG)4 | double-stranded | CG deletions; 0.5% mutations at the first dG, 0.1% at the second dG, 0.2% at the third dG, and 0.3% at the fourth dG in NER-deficient mutant but no mutations in repair-proficient cells (64) |

| 5 | 2 | E. coli, mismatch repair deficient derivatives of MV1932 and NR9232 | CpGpA | double-stranded | one G→T transversions among 282 transformants in non-SOS-induced MV1932 derivative but no mutations in the same strain following SOS induction; no mutations in other strains tested including NER mutant (65) |

| 6 | 2 | E. coli derivatives of AB1157 | TpGpT | double-stranded | no mutations (66) |

| 7 | 2 | E. coli derivatives of AB1157 | TpGpT | single-stranded | no mutations (66) |

| 8 | 2 | E. coli AB1157 | CpGpA | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 0.3% of G→T transversions, 0.4% of G→Α transitions, and 0.3% of G→C transversions (67)a |

| 9 | 14 | COS-7 | CpGpT | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 6.9% of G→T and 0.9% of G→C transversions (61)a |

| 10 | 14 | XPA | CpGpA | double-stranded | single base substitutions; 5.9 and 3.6% of G→T transversions, 1.0 and 0.4% of G→Α transitions, and 0.6 and 0.6% of G→C transversions detected in two independent studies (68,69)a |

| 11 | 2 | COS-7 | CpGpA | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 3.8 and 2.6% of G→T transversions, 1.0 and 0.3% of G→Α transitions, and 2.6 and 0.6% of G→C transversions detected in two independent studies (67,70)a |

| 12 | 2 | human fibroblasts | CpGpA | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 8.7% of G→T transversions, 1.1% of G→Α transitions, and 1.1% of G→C transversions (71)a |

| 13 | 2 | HeLa | CpGpA | double-stranded | single base substitutions; 0.5% of G→T transversions and 0.5% of G→Α transitions when the adduct was incorporated in the leading strand; 1% of G→T transversions when the adduct was incorporated in the lagging strand (68,69)a |

| 14 | 2 | XPA | CpGpA | double-stranded | no mutations above background levels (68,69) |

| 15 | 15 | COS-7 | CpGpA | single-stranded | single base substitutions. 0.8% of G→T transversions (70)a |

| 16 | 3 | COS-7 | CpGpA | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 5.6% of G→T and 2.6% of G→C transversions (72) |

| 17 | 3 | XPA | CpGpA | double-stranded | single base substitutions; 8.8 and 6.3% of G→T transversions, 1.5 and 1.5% of G→Α transitions, and 1.5 and 2.6% of G→C transversions detected in two independent experiments (69)a |

| 18 | 4 | COS-7 | CpGpA | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 3.1% of G→T transversions, 0.5% of G→Α transitions, and 1.1% of G→C transversions (76)a |

| 19 | 4 | XPA | CpGpA | double-stranded | single base substitutions; 2.3 and 2.5% of G→T transversions, 1.7 and 1.8% of G→Α transitions, and 0.6 and 0.6% of G→C transversions detected in two independent experiments (77)a |

| 20 | 5 | COS-7 | CpGpA | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 4.0% of G→T transversions, 1.2% of G→Α transitions, and 0.9% of G→C transversions (76)a |

| 21 | 5 | XPA | CpGpA | double-stranded | single base substitutions; 5.8 and 7.3% of G→T transversions, 0.6 and 0.7% of G→Α transitions, and 2.9 and 3.3% of G→C transversions detected in two independent experiments (77)a |

| 22 | 6 | COS-7 | CpGpA | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 3.2% of G→T transversions, 0.6% of G→Α transitions, and 0.3% of G→C transversions (82)a |

| 23 | 7 | COS-7 | CpGpA | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 2.9% of G→T transversions, 1.5% of G→Α transitions, and 0.6% of G→C transversions (82)a |

| 24 | 8 | COS-7 | CpGpA | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 0.8% of G→T and 0.3% of G→C transversions (82)a |

| 25 | 9 | COS-7 | CpGpA | single-stranded | single base substitutions; 0.25% of G→T and 0.25% of G→C transversions (82)a |

For purposes of comparison, percentiles were calculated from primary data that were reported as the number of mutants.

The adduct was positioned at the second G of the repetitive sequence.

Moriya and co-workers examined the mutagenic properties of the PdG adduct 14 (Figure 2) (61), which can serve as a model for the ring-closed form of the acrolein-derived 1,N2-dG adducts 2 and 3. The adduct in the CpGpT sequence was incorporated into a single-stranded vector, and following replication of the modified vector in E. coli strain AB1157, G→T transversions were observed at 100% frequency. When cells were prechallenged by UV irradiation to induce an SOS response, an overall mutation frequency was 68%, and in addition to G→T transversions, other types of base substitutions were also observed (Table 1, row 1). However, Burcham and Marnett did not detect any mutations following replication of PdG-containing double-stranded DNA in noninduced E. coli strain JM105, when the adduct was positioned in the TpGpT sequence; in SOS-induced JM105 cells, G→T transversions and G→A transitions were observed at low frequencies (∼1% of each type) (Table 1, row 2) (62). The spectra of mutations were different when PdG was positioned at the second dG of the repetitive (CpG)3 sequence and replicated in the same JM105 strain. In this case, frameshift mutations consisting of mostly CG deletions occurred in 2.5% of the progeny DNAs (Table 1, row 3) (63). In the repetitive (CpG)4 sequence, frameshift mutations were also detected in the NER-deficient strain that was derived from AB1157 E. coli but not in the corresponding NER-proficient strain (Table 1, row 4) (64). The highest mutation frequency was observed with the PdG modification at the first dG of the CpG repeat, followed by adduction at the fourth and third positions. Thus, the local sequence context and the genetic background of the bacterial strain can modulate the mutagenic properties of PdG and probably structurally related adducts.

The mutagenic properties of γ-OH-PdG 2 have been investigated in E. coli in three independent studies (Table 1, rows 5−8) (65−67). These studies utilized different vector systems and assayed bacterial strains with various genetic backgrounds. In addition, experiments were conducted using both induced and noninduced cells. Nevertheless, mutations (G→T transversions) were consistently observed at very low frequencies (<1%) (65,67) or not detected at all (66).

The PdG adduct 14 induced single base substitutions, predominantly G→T transversions, at an overall frequency of ∼8% when a single-stranded vector was replicated in African green monkey kidney (COS-7) cells (Table 1, row 9) (61). The mutagenic properties of PdG were also investigated in a double-stranded vector in NER-deficient human xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group A (XPA) cells. In this system, the adduct was also moderately mutagenic; specifically, it caused 4.6−7.5% base substitutions, mostly G→T transversions (Table 1, row 10) (68,69). In contrast to PdG, the replication fidelity of the γ-OH-PdG adduct 2 varied in mammalian cells depending on whether a single- or double-stranded vector was utilized (Table 1, rows 11−14). Specifically, this adduct induced transversions and transitions at overall frequencies of 3.5−7.4% in COS-7 cells (67,70) and ∼11% in normal human fibroblasts (71) when a single-stranded vector was replicated; the primary events were G→T transversions. However, γ-OH-PdG was only marginally miscoding (∼1%) when a double-stranded vector was replicated in HeLa cells (68), and no mutations above the background levels were detected in XPA cells (68,69). Interestingly, the N2-(3-hydroxypropyl)-dG adduct 15, which cannot form a cyclic adduct and serves as a model for the ring-opened form of γ-OH-PdG 1 (Figure 2) or its hydrate 19 (Scheme 4), was miscoding only in ∼0.8% of bypass events in COS-7 cells (Table 1, row 15), even though a single-stranded vector was used (70). Collectively, these observations suggest that during replication bypass of γ-OH-PdG in mammalian systems, mutations are caused primarily by the ring-closed form of the adduct but not the corresponding ring-opened aldehyde 1 (R = H). This conclusion is consistent with NMR structural analyses, showing the ability of the ring-opened adduct to maintain Watson−Crick hydrogen bonding at the damaged site (52).

The α-OH-PdG adduct 3 was moderately mutagenic in COS-7 (8.3%) and XPA (12.5 and 10.4%) cells (Table 1, rows 16 and 17) (69,72), yielding a frequency and spectrum of mutations similar to PdG (61,68,69). The replication of α-OH-PdG in single-stranded vs double-stranded vectors was comparably mutagenic, which was also similar to PdG.

4.2. Crotonaldehyde-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts

Crotonaldehyde is mutagenic in bacteria (73), genotoxic and mutagenic in human lymphoblasts (74), and induces liver tumors in rodents (75). The mutagenicities of (6R,8R)- and (6S,8S)-crotonaldehyde adducts 4 and 5 (Table 1, row 18 and 20) were ∼5 and ∼6%, respectively, when a single-stranded, site specifically modified vector was replicated in the COS-7 system (76). G→T transversions were the predominant mutations for these adducts, followed by G→C transversions and G→A transitions. Moriya and co-workers examined mutagenic properties of crotonaldehyde adducts in XPA cells using a double-stranded vector (77). They observed that the (6R,8R) adduct 4 miscoded at a ∼5% frequency, while the (6S,8S) adduct 5 miscoded at a ∼10% frequency (Table 1, rows 19 and 21). For both, the major events were G→T transversions, but G→A transitions were also observed at a comparable level for the (6R,8R) adduct 4. G→C transversions were the second most common events for (6S,8S) adduct 5. Significantly, both adducts created stronger DNA replication blocks than did γ-OH-PdG 2 but were weaker replication blocks than α-OH-PdG 3. Both diastereomers 4 and 5 were more miscoding than γ-OH-PdG 2 in a double-stranded vector. Finally, the miscoding potency of the (6S,8S) adduct 5 was comparable to that of PdG 14 and α-OH-PdG 3. Overall, these observations suggest that crotonaldehyde adducts predominantly exist in the ring-closed form at the replication fork; this is consistent with the data from NMR analyses showing that crotonaldehyde adducts are only partially open to the respective aldehyde forms (35).

4.3. 4-HNE-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts

4-HNE induces a DNA damage response in Salmonella typhimurium(78) but is inactive in bacterial mutagenesis assays (55). The lower homologue 4-hydroxypentenal was found to be mutagenic in bacteria (55); it was suggested that the cytotoxicity of 4-HNE masked its genotoxicity. Consistent with this hypothesis are the observations that 4-HNE increases the mutation rates in the lacZ gene of M13 phage transfected into E. coli(79) and causes mutations in Chinese hamster lung cells (80) and human lymphoblastoid cells (28). Mutational spectra have been determined in the supF gene following replication of a 4-HNE-treated vector DNA in normal human and XPA fibroblasts; in both cell types, G:C→T:A transversions were most prevalent (81). Site-specific mutagenesis revealed that the 4-HNE-derived 1,N2-dG adducts induced base substitutions at frequencies of 0.5−5.0% in COS-7 cells (Table 1, rows 22−25); G→T transversions were the predominant type of mutations. The adducts having (6S,8R,11S) and (6R,8S,11R) stereochemistry (6 and 7) were more mutagenic than the (6S,8R,11R) and (6R,8S,11S) adducts (8 and 9) (82).

These data indicate that enal-derived 1,N2-dG adducts are not strongly miscoding. In all cases, the predominant mutations were G→T transversions. However, it should be noted that although deletions and tandem mutations were detected following replication of randomly modified vectors (58,81), no studies have been conducted to evaluate mutagenicity of enal adducts in deletion- and tandem mutation-prone repetitive sequences. Such studies would be of interest since both the PdG and the M1dG adducts were shown to induce two-base deletions in the repetitive CpG dinucleotide sequences in E. coli(63,64), and M1dG caused this type of mutation in mammalian cells (64).

5. Replication Bypass of Enal-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts

5.1. Replication Bypass of Acrolein-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts by E. coli DNA Pols

As discussed above, replication bypass of the γ-OH-PdG adduct 2 is nearly error-free in E. coli(65−67); the level of inhibition of DNA synthesis past the lesion was estimated at ∼27% (65). Several biochemical studies have been conducted to examine which E. coli polymerase (pol) is capable of catalyzing the bypass of the γ-OH-PdG adduct 2 in vitro. The major replicative pol in E. coli, pol III, appeared to be completely incompetent in carrying out this reaction; DNA synthesis was terminated one nucleotide before the lesion (83). The ring-opened N2-(3-hydroxypropyl)-dG model adduct 15 was also a complete block to replication by pol III (83). Thus, pol III is unlikely to be involved in intracellular bypass of γ-OH-PdG.

In vitro bypass experiments were conducted with the exonuclease-deficient Klenow fragment (Kf) of pol I to investigate whether another essential E. coli pol, pol I, can be involved in bypass of γ-OH-PdG (65,66). γ-OH-PdG posed a significant block to replication, and when the reactions were performed with individual deoxynucleotide triphosphates using −1 primers (the 3′ primer terminus was positioned immediately prior to the adducted site), incorporation opposite the adduct was most efficient in the presence of dGTP and dATP but not the correct dCTP (65,66). These patterns of misincorporation were very similar to those previously observed for the ring-closed PdG adduct 14(84,85). The difference in the miscoding propensities of γ-OH-PdG and PdG became more apparent when the reactions were conducted using various 0 primers (the 3′ primer termini are positioned opposite the adducted site) (69). The primer with dC at the 3′ terminus opposite the γ-OH-PdG adduct was more readily extended than primers with either dA, dG, or dT. However, extension on the PdG-containing template was more efficient from the dT primer terminus than from dA and dC termini. These data provided valuable insights into the mechanism of bypass of the γ-OH-PdG adduct, confirming the hypothesis (52) that the ring opening would facilitate the efficiency and increase the fidelity of translesion synthesis. However, for the reasons listed below, these data are not sufficiently informative to speculate on a possible role of pol I in intracellular bypass of this lesion. First, the mutagenic outcome of replication depends on both the identity of nucleotides inserted opposite the adduct and the relative efficiencies of extension from the products of insertion. In the case of γ-OH-PdG, it is possible that the efficient extension from dC opposite the adduct will correct the apparent error-prone insertion step, directing the bypass reaction toward preferential formation of the error-free products. Second, all of the in vitro studies described above were performed using exonuclease-deficient Kf but not the intact pol I. It requires further evaluation whether the 3′ to 5′ and 5′ to 3′ exonuclease activities of pol I are capable of correcting the replication errors opposite the γ-OH-PdG adduct. Finally, it is unknown how the equilibrium is shifted between the ring-closed and the ring-opened species when the adduct is subjected to replication in cells. Germane to this question, Kf exo− only inserted dCTP opposite the ring-opened N2-(3-hydroxypropyl)-dG model adduct 15.2 If the rate of the replication fork progression is faster than the rate of the ring closure, pol I, if involved, will replicate past the adduct in its less miscoding form. Thus, the cellular role for pol I in error-free bypass of the γ-OH-PdG adduct cannot be excluded.

In addition to pol I and pol III, E. coli possesses three DNA damage-inducible DNA pols; these so-called SOS DNA pols include pol II (polB), pol IV (dinB), and pol V (umuDC) (reviewed in ref (86)). Whereas the biological function of pol II is not clearly defined, pol IV and pol V have previously been shown to be involved in translesion DNA synthesis (TLS). Recently, the abilities of SOS pols to synthesize DNA past the γ-OH-PdG adduct 2 and reduced γ-OH-PdG adduct 15 have been examined (83). Both pol II and pol V were strongly inhibited by these lesions one nucleotide prior to the site of modification. The blockage was less severe on the DNA substrate containing the ring-opened, reduced γ-OH-PdG, and pol II extended a significant percentage of the primers past this lesion to the expected full-size products. The γ-OH-PdG adduct also blocked pol IV one nucleotide prior to the lesion and modestly opposite the lesion, but the extent of blockage was not as strong as in the pol II- and pol V-catalyzed reactions. The ring-opened, reduced γ-OH-PdG adduct had minimal effect on DNA synthesis by pol IV. Single-nucleotide incorporation analyses using a −1 primer revealed that pol IV preferentially incorporated the correct nucleotide, dC, opposite both of these lesions.

To address the question of which DNA pol(s) is (are) responsible for the replication bypass of γ-OH-PdG, Moriya’s group (65) utilized an E. coli mutant that lacks all SOS DNA pols. Vector DNAs containing a site-specific γ-OH-PdG were replicated in cells either following stress induction or with no stress. Under both conditions, no significant differences in bypass efficiency were observed relative to the parental strain, and no effect on the mutagenic outcome was apparent. The authors concluded that non-SOS pol(s) catalyze(s) error-free TLS past γ-OH-PdG in E. coli. In view of the recent data showing the complete inability of pol III to bypass this adduct (83), pol I seems to be primarily responsible for this function in vivo.

The ability of Kf to conduct TLS has also been tested for the α-OH-PdG adduct 3(69,87). When primer extensions were catalyzed by Kf exo+, DNA synthesis was strongly blocked by α-OH-PdG one nucleotide prior to the lesion and also opposite the lesion; however, formation of the full-length product was detected (87). In the Kf exo−-catalyzed reactions, limited extension was observed from the correctly paired 0 primer (dC opposite the lesion), and the efficiency of extension was comparable to that shown for the PdG adduct 14(69).

5.2. Replication Bypass of Acrolein-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts by Eukaryotic DNA Pols

As summarized in the previous section, the majority of bypass events are error-free during replication through the γ-OH-PdG adduct 2 in mammalian cells. The efficiency of intracellular bypass of γ-OH-PdG was estimated to be ∼73% (68). However, γ-OH-PdG caused mutations at frequencies of ∼3.5−11.0%, specifically when a single-stranded DNA vector was used to assess the adduct mutagenicity (67,70,71). Thus, for the eukaryotic system, it is important not only to identify the DNA pols that are involved in bypass of this adduct in vivo but also to evaluate their potential to contribute to the mutagenic events in this process.

The majority of the chromosomal DNA in eukaryotic cells is replicated by two DNA pols, pol ε and pol δ (88). The γ-OH-PdG lesion 2 strongly blocked synthesis by human pol ε one nucleotide before the lesion, and following an extremely weak incorporation opposite the lesion, replication was completely aborted (67). DNA synthesis by calf thymus pol δ was also strongly inhibited one nucleotide before γ-OH-PdG, but limited bypass was observed in the presence of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (67). In reactions supplemented with individual deoxynucleotide triphosphates using a −1 primer, no insertion opposite the lesion was detected in the presence of dCTP. However, the primers were extended, even though inefficiently, in the presence of dATP, dGTP, and dTTP. The ring-opened, reduced γ-OH-PdG adduct 15 also strongly inhibited the primer extension catalyzed by yeast pol δ (89). Collectively, these data indicate that pol ε and pol δ are unlikely to have a major role in synthesizing DNA past γ-OH-PdG in vivo, and neither of them can significantly contribute to the error-free bypass of this lesion.

The ability to replicate past the PdG adduct 14 was examined for human pol β (90). This pol plays a role in repair-associated gap-filling DNA synthesis (88) and also may be involved in bypass of certain DNA lesions (91,92). The bypass of PdG by this pol was inefficient and highly error-prone. Analysis of the bypass products revealed that the nucleotide inserted opposite the lesion site was complementary to the nucleotide on the 5′ side of the PdG lesion of the template strand; subsequently, the primers were extended, generating products with either mismatches or deletions.

On the basis of the above observations, we hypothesized (71) that in eukaryotes, replication bypass of the γ-OH-PdG adduct requires the involvement of the specialized TLS pols. To date, three TLS pols have been identified in the model eukaryotic organism, yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae(88,93,94). They include two members of the pol Y family, pol η and Rev 1, and one member of the B family, Rev 3, the catalytic subunit of pol ζ. Human cells possess two additional Y family pols, pol ι and pol κ, the latter of which is an orthologue of E. coli pol IV (88,93,94). The potential of eukaryotic TLS pols to bypass γ-OH-PdG and related model adducts has been extensively investigated and is discussed below.

In contrast to the replicative pols, both the yeast and the human variants of pol η can replicate past γ-OH-PdG 2 by incorporating the correct nucleotide, dC, opposite the lesion and extending the primer beyond a dC paired opposite this adduct (71). Relative to the nondamaged dG, the efficiencies of incorporation and the subsequent extension were reduced ∼190- and ∼7.5-fold in reactions catalyzed by yeast pol η and ∼100- and ∼19-fold in reactions catalyzed by human pol η (71). Although DNA synthesis past γ-OH-PdG by yeast pol η was relatively accurate, the human enzyme misincorporated the purine nucleotides opposite γ-OH-PdG with frequencies of ∼10−1. The PdG adduct 14 strongly blocked synthesis by pol η, and in the case of the human enzyme, the correct nucleotide, dC, was incorporated opposite the lesion less efficiently than any of the incorrect nucleotides (71). In contrast, the reduced γ-OH-PdG adduct 15 was significantly less blocking and less miscoding than γ-OH-PdG. The incorporation of the correct nucleotide opposite this adduct was especially efficient in reactions catalyzed by human pol η and was even better than opposite the nondamaged dG. Thus, these results suggest that DNA synthesis past γ-OH-PdG by pol η involves the ring-opened aldehydic form of the lesion. This notion, specifically regarding the extension step of the bypass reaction, is consistent with studies showing that in duplex DNA at neutral pH the aldehydic form predominated (52).

Replication of a single-stranded DNA vector containing γ-OH-PdG in wild-type vs pol η-deficient xeroderma pigmentosum variant (XPV) cells revealed a decreased frequency of base substitutions (71). Alterations in the mutational spectrum were consistent with biochemical data showing that human pol η preferentially misincorporated the purine nucleotides opposite γ-OH-PdG; G→T and G→C transversions but not G→A transitions were reduced in XPV cells relative to wild-type cells. Collectively with the observation that nucleotide incorporation opposite γ-OH-PdG by human pol η was most efficient in the presence of the correct nucleotide, dC (71), these data suggest that pol η can contribute to both error-free and mutagenic bypass of the γ-OH-PdG lesion in cells. When the adduct was incorporated into a double-stranded vector, frequencies of mutations in XPV cells were not significantly different from those measured for XPA and HeLa cells (87). Given the very low overall frequencies of damage-induced mutations in all of the strains that were utilized in this study, it was not possible to identify a specific role for pol η in bypass of the γ-OH-PdG adduct. However, these data and the results of our study described above (71) are consistent in demonstrating that in humans, pol η is not solely responsible for TLS past this lesion.

Pol ι incorporated dC opposite γ-OH-PdG 2 with nearly the same efficiency as opposite a nonadducted template dG; however, further extension of the primer beyond the lesion was significantly inhibited (95). Interestingly, the relative efficiencies for dC incorporation opposite the ring-closed PdG adduct 14 and the ring-opened, reduced γ-OH-PdG adduct 15 were almost equal (89), and they were comparable with that measured for γ-OH-PdG (95). Therefore, in striking contrast to pol η, it appears that ring opening is not required for efficient nucleotide incorporation opposite γ-OH-PdG by pol ι. Pol ι also incorporated dT opposite γ-OH-PdG, PdG, and reduced γ-OH-PdG (89). The efficiencies of dT incorporation were ∼3−7 times less than the corresponding efficiencies of dC incorporation, and these parameters were similar to the relative efficiency of dT incorporation opposite the unmodified dG.

The ability of pol ι to accommodate and recognize the PdG adduct 14, which is incapable of Watson−Crick base pairing and adopts a syn conformation in DNA (42−44), suggested a unique replication mechanism that involves the utilization of the Hoogsteen edge of the template dG. The crystallographic analyses of pol ι ternary complexes showed that, indeed, the purine bases are “pushed” by the incoming complementary dNTP from the anti to syn conformation, exposing the Hoogsteen edge of the template base for nascent base pairing (96). Similar conformations were also observed for the adducted purines, 1,N6-etheno-dA and N2-ethyl-dG, within the pol ι active site (97,98); however, no crystallographic data on cyclic 1,N2-dG adducts bound to pol ι have been reported.

Pol ι was unable to extend from a dC placed opposite the PdG adduct 14(89). In contrast, the extension efficiency from a dC paired with the reduced γ-OH-PdG adduct 15 was ∼2-fold higher than from a dC paired with the nondamaged dG. No significant extension was observed from a dT primer terminus placed opposite either of these two adducts. These results suggest that ring opening is mandatory for the efficient extension in pol ι-catalyzed bypass of the γ-OH-PdG adduct 2. It is not surprising given the fact that, in cocrystal complexes, the only base that adopts a syn conformation is the template base of the nascent base pair (96−98). It can be envisioned that, following incorporation of the anti-oriented dC opposite the syn-oriented γ-OH-PdG, the adducted base will assume the regular anti conformation and undergo ring opening opposite the primer dC. Subsequently, such a primer template will be extended by pol ι, leading to the overall efficient bypass of the lesion. However, the major site of blockage occurs following nucleotide incorporation opposite γ-OH-PdG (95). Collectively, these observations suggest that either the ring opening of the adduct or the syn to anti rotation of the adducted base about the glycosyl bond limits pol ι-catalyzed bypass of this lesion.

DNA synthesis by human pol κ was strongly blocked by the presence of γ-OH-PdG 2 one nucleotide prior to the site of modification (95). However, this pol was able to extend from a dC opposite the lesion; the efficiency of extension was about 3-fold higher than that from a dC opposite the nondamaged dG (95). Pol κ also efficiently and accurately incorporated dC opposite the ring-opened, reduced γ-OH-PdG adduct 15 and efficiently extended from such a dC (89). In contrast, the ring-closed PdG adduct 14 represented a severe block to synthesis by pol κ at both the insertion and the extension step. Thus, effective TLS past γ-OH-PdG by pol κ is possible only when the adduct exists in its ring-opened form. This conclusion is in agreement with the crystallographic analyses of the pol κ complexes showing that this pol relies on the Watson−Crick base pairing for the recognition of the template base (99).

At this time, no data have been reported showing pol κ involvement in cellular bypass of the γ-OH-PdG adduct. However, evidence has been obtained that strongly supports a role for pol κ in error-free TLS past various bulky N2-dG adducts (100−105). The crystallographic analysis of pol κ in the complex with nondamaged DNA substrate and an incoming nucleotide revealed that the minor groove portion at the primer−template junction is quite open (99), which may explain the tolerance of the pol toward these minor groove lesions. Taking into consideration that pol κ is able to proficiently replicate through the reduced model adduct 15, we anticipate this pol has a central role in cellular bypass of γ-OH-PdG when the adduct enters the replication complex in its ring-opened form. Additionally, pol κ may extend from a dC that was inserted opposite the lesion by a different pol, for example, pol ι. The possibility that pol κ could also extend from a dT opposite γ-OH-PdG, the consequence of misincorporation by pol ι, was considered (95) but was ruled out since pol κ was not capable of extension from a dT placed opposite either γ-OH-PdG, PdG, or reduced γ-OH-PdG in vitro (89,95).

Rev1 is a template-dependent deoxycytidyl transferase that accurately incorporates a dC opposite dG but is not able to efficiently incorporate opposite other template nucleotides (106). Yeast Rev1 incorporated a dC opposite γ-OH-PdG 2 with an efficiency approaching that for dC incorporation opposite the nondamaged dG (107). As expected, however, Rev1 failed to carry out the subsequent extension, with no nucleotide incorporation detected opposite the downstream dC. Rev1 incorporated a dC opposite the PdG adduct 14 with nearly the same efficiency and fidelity as it did opposite the nondamaged dG (108).

Crystallographic analyses of the ternary complexes of yeast Rev 1 revealed the structural basis for how this pol promotes proficient and error-free bypass of exocyclic dG adducts (108,109). In the complex with nondamaged DNA substrate, the template dG is extruded from the DNA helix and held in this position by hydrogen bonds that are formed between the Hoogsteen edge of dG and pol amino acids. Incoming dC does not directly interact with the template dG but pairs with an arginine residue, thereby ensuring the incorporation of dC over other incoming nucleotides (109). Significantly, Rev1 accommodates the template PdG with little or no alteration in structure; PdG is extruded from the DNA helix in a manner similar to the nondamaged dG, allowing the proper interactions between incoming dC and a “surrogate” arginine (108).

Pol ζ is a protein complex comprised of the catalytic subunit Rev3 and the accessory subunit Rev7 (93). In contrast to Rev1, yeast pol ζ was significantly inhibited at the nucleotide insertion step opposite the γ-OH-PdG adduct 2; the efficiency of dC incorporation was reduced ∼20-fold relative to the nondamaged control (107). However, this pol was proficient in extending from a dC opposite the lesion with only ∼3-fold reduction in efficiency relative to the nondamaged control (107). Pol ζ was unable to insert nucleotides opposite the ring-closed PdG adduct 14(108), although it could extend from dC paired with the ring-closed PdG adduct. However, the efficiency of the extension was ∼35-fold lower than that determined for the corresponding nondamaged control. On the basis of these observations, it has been suggested that Rev1 and pol ζ function sequentially to bypass γ-OH-PdG and other exocyclic dG adducts (107). It is worth noting that although ring opening will facilitate the overall TLS efficiency by promoting the pol ζ-catalyzed extension step, this structural rearrangement is not absolutely required for the Rev1/pol ζ-mediated bypass of the γ-OH-PdG adduct.

From the results of assays in vitro using various eukaryotic DNA pols, we conclude the following. (1) Error-free bypass of the ring-opened, aldehyde adduct 1 (R = H) can be conducted by either pol η or pol κ, such that insertion opposite the lesion and subsequent extension are performed by the same pol (two-step, one-pol mechanism). The common structural feature of pol η and pol κ is that they make use of the Watson−Crick geometry for recognition of the template base (99,110,111). In this respect, pol η and pol κ are similar to replicative pols, but in contrast to the replicative pols, they better tolerate minor groove perturbations caused by the open form of the γ-OH-PdG adduct. (2) Error-free bypass of the aldehyde adduct 1 (R = H) can also be achieved by the sequential action of TLS pols such that either Rev1 or pol ι will insert opposite the lesion, while pol ζ, pol η, or pol κ will extend (two-step, two-pol mechanism). As discussed, pol ι is also able to catalyze the extension, but its dissociation from the primer template prior to extension seems necessary. (3) Rev1 or pol ι can initiate error-free bypass of the ring-closed adduct 2 by insertion of the correct nucleotide opposite the lesion; these two TLS pols are unique in that they do not rely on the Watson−Crick geometry for recognition of the template base. Following the ring opening and rotation of the adducted base from the syn into the anti conformation, pol ζ, pol η, or pol κ will catalyze the subsequent extension. Pol ζ will likely do so even if the adduct is still in its ring-closed form. (4) In human cells, pol η contributes to the mutagenic bypass of the γ-OH-PdG 2 adduct by inserting dA and dG opposite the ring-closed form of the adduct. Pol ι may cause mutations by inserting dT opposite either form of the adduct. Non-TLS pols, for example, pol δ, may also misincorporate opposite the lesion. Further analyses are required to identify DNA pols that would be capable of the extension from the various mismatched primer termini opposite γ-OH-PdG, thus, potentially contributing to the mutagenic bypass of this adduct.

The consequences of cellular processing of the α-OH-PdG adduct 2, such as the extent of the blockage to replication and the mutational outcome, are remarkably similar to those caused by the ring-closed PdG adduct 14(61,68,69,72). Not surprisingly, the action of many TLS pols on the α-OH-PdG-containing templates is similar to that of the PdG-containing templates. Nucleotide insertion opposite the α-OH-PdG adduct and subsequent extension by calf thymus pol δ in the presence of PCNA were poor (87). Pol δ was able to resume DNA synthesis only when the primer terminus was ≥7 nucleotides past the α-OH-PdG lesion. The exonucleolytic proofreading activity of pol δ predominated when the primer terminus was six or fewer nucleotides past the lesion. Rev1 inserted dC opposite α-OH-PdG, and pol ι inserted dC and dT, but these pols could not catalyze the subsequent extension (87). Pol η, pol κ, and pol ζ were significantly blocked one nucleotide prior to α-OH-PdG, incorporating incorrect nucleotides opposite this adduct with a much higher preference over the correct dC. Pol η and pol ζ could extend from dC opposite α-OH-PdG but very inefficiently. Pol η, pol ζ, and pol κ were also able to extend from various mismatched primer termini opposite α-OH-PdG. Replication of vector DNA containing α-OH-PdG in pol η-deficient XPV cells resulted in ∼10-fold reduced frequency of base substitutions relative to the XPA cells, while the complementation of XPV cells with pol η activity led to ∼2.4-fold increased frequency of base substitutions (87). From these results, it was concluded that pol η was not critical to error-free bypass of α-OH-PdG, but it significantly contributed to mutagenic bypass. Regarding the accurate TLS past α-OH-PdG in mammalian cells, in vitro analyses suggest that Rev1 and pol ι could be involved in the insertion of the correct nucleotide opposite the adduct. However, it is uncertain which pol(s) would be able to efficiently carry out DNA synthesis beyond this step.

5.3. Replication Bypass of 4-HNE-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts by Eukaryotic DNA Pols

On the basis of the observation that proficient and accurate TLS past γ-OH-PdG can be accomplished by the sequential action of pol ι and pol κ, it was hypothesized that these pols would also be able to bypass other exocyclic dG adducts (112). Indeed, pol ι could incorporate dC opposite the (6S,8R,11S)- and (6S,8R,11R)-4-HNE-dG adducts 6 and 8 with the efficiencies reduced only ∼3-fold relative to that observed for incorporation opposite nondamaged dG but was not able to carry out the extension. In contrast to pol ι, pol κ was inhibited at the insertion step, but it was proficient in extending from the dC primer termini opposite these lesions. The efficiencies of both insertion and extension by pol κ were dependent on the identity of the lesion. Although no nucleotide incorporation was detected opposite (6S,8R,11S)-4-HNE-dG 6, a limited incorporation of dC was observed opposite (6S,8R,11R)-4-HNE-dG 8. The efficiency of extension from a dC opposite (6S,8R,11S)-4-HNE-dG 6 by pol κ was reduced ∼5-fold, whereas the efficiency of extension from a dC opposite (6S,8R,11R)-4-HNE-dG 8 was comparable to the corresponding control value. Overall, these data indicate that the sequential action of pol ι and pol κ can promote efficient and error-free TLS past the 4-HNE-1,N2-dG lesions.

The ability of human pol η to bypass 4-HNE-dG lesions was also examined (112). This pol was strongly inhibited by the (6S,8R,11S)-4-HNE-dG and (6S,8R,11R)-4-HNE-dG adducts 6 and 8 at both the insertion and the extension steps. In addition, pol η was prone to misincorporate nucleotides opposite these lesions. Although pol η was impaired at extending from a dC opposite both lesions, the blockage was less severe on the (6S,8R,11R)-4-HNE-dG-containing template than on the (6S,8R,11S)-4-HNE-dG-containing template; the efficiency of extension was reduced ∼20- and ∼500-fold, respectively.

It is significant that, for both pol κ and pol η, (6S,8R,11R)-4-HNE-dG 8 was less inhibitory to DNA synthesis than (6S,8R,11S)-4-HNE-dG 6, possibly because adduct 8 undergoes ring opening more readily than adduct 6. Consistent with this interpretation, (6S,8R,11R)-4-HNE-dG 8 was less miscoding than (6S,8R,11S)-4-HNE-dG 6 during replication of site specifically modified vector DNA in COS-7 cells (82).

5.4. Replication Bypass of the Model PdG Adduct by Sulfolobus solfataricus DNA Pol IV

To elucidate the structural basis of how replication errors can occur during bypass of enal-derived 1,N2-dG adducts, structures of ternary pol-DNA-dNTP complexes were determined for the Y-family S. solfataricus DNA pol IV (Dpo4) bound to a DNA substrate that contained the ring-closed PdG adduct 14 at the templating site (113). Three template 18-mer·primer 13-mer sequences, 5′-d(TCACXAAATCCTTCCCCC)-3′·5′-d(GGGGGAAGGATTT)-3′ (template I), 5′-d(TCACXGAATCCTTCCCCC)-3′·5′-d(GGGGGAAGGATTC)-3′ (template II), and 5′-d(TCATXGAATCCTTCCCCC)-3′·5′-d(GGGGGAAGGATTC)-3′ (template III), where X = PdG, were used in crystallographic analyses. With templates I and II, ternary complexes were obtained with an incoming dGTP. For template III, a ternary complex was obtained with an incoming dATP. In each of these three ternary complexes, the incoming nucleotide (dGTP or dATP) did not pair with PdG but instead with the 5′-neighboring nucleotide (dC on templates I and II or dT on template III), utilizing Watson−Crick geometry; the PdG adduct remained in the anti conformation about the glycosyl bond. Thus, all three ternary complexes were of the “type II” structure described for ternary complexes with native DNA (114). It can be inferred from these data that one mechanism by which Dpo4 might bypass PdG is by accommodating both PdG and the 5′-neighboring template nucleotide within its spacious active site and incorporating an incoming nucleotide opposite the 5′-neighboring nucleotide.

Replication bypass experiments with a PdG-containing template primer in a Cp(PdG)pA template sequence showed that Dpo4 inserted dG and dA when challenged by the PdG adduct. Although the structural basis for incorporation of dA is currently unknown, insertion of dG presumably reflects the “type II” structure that was observed in crystallographic analyses. These results provide insight as to how −1 frameshift mutations might be generated by the PdG adduct. The anticipated mechanism involves utilization of the 5′-neighboring template nucleotide for base pairing, a process referred to as dNTP-stabilized misalignment (115), followed by the subsequent extension. However, if the primer realigns prior to the extension step, sequence-dependent base substitutions could occur as a consequence of such replication.

6. Repair of Enal-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts

Identification of the biological mechanisms involved in repair and tolerance of enal-derived 1,N2-dG adducts has been addressed in several studies, mostly focusing on the NER and base excision repair (BER) pathways. Although some lesions can be repaired by either mechanism, NER is primarily responsible for removal of bulky, structure-perturbing DNA adducts (reviewed in ref (116)). BER, on the other hand, eliminates a variety of damaged bases, such as products of deamination, oxidation, and alkylation, utilizing DNA glycosylases as the initiating enzymes (reviewed in ref (117)).

Marnett’s group investigated the removal of PdG adduct 14 by comparing the mutation frequency and strand bias following replication of site specifically modified M13 genomes in wild-type and various repair-deficient strains of E. coli(118). The NER-deficient uvrA− and uvrB− strains, but not the strains lacking the functional 3-methyladenine glycosylase, displayed defective processing of PdG. Additionally, reactions were conducted in vitro to examine whether PdG can be removed by NER proteins; both E. coli UvrABC excinuclease and Chinese hamster ovary cell-free extracts were competent in making dual incisions around the lesion (118).

The cellular processing of γ-OH-PdG 2 was examined in E. coli using a site specifically modified double-stranded vector that was replicated in wild-type, uvrA−, and recA− strains (65). Analyses of the progeny DNAs indicated that this adduct was also excised by the NER pathway. In addition, the block to DNA synthesis was partially overcome by a RecA-dependent mechanism, presumably daughter strand gap repair. Consistent with the role of bacterial NER in γ-OH-PdG removal, incision of this adduct was demonstrated in the presence of a reconstituted prokaryotic NER system of recombinant proteins in which UvrA and UvrB were derived from Bacillus caldotenax and UvrC from Thermotoga maritima(119).

Mutagenic properties of γ-OH-PdG 2 were assessed in an E. coli double mutant, deficient in exonuclease III and endonuclease IV (66), two major apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases associated with the BER pathway. Suggesting that BER is unlikely to be involved in the removal of γ-OH-PdG, replication of the modified vector did not result in the occurrence of base substitutions in this mutant.

Kinetics of recognition and repair of 4-HNE-dG lesions were investigated in human nuclear extracts by monitoring both the removal of adducts from plasmid DNA substrates and the subsequent repair-associated DNA synthesis (120). These data indicated that the repair was NER-dependent with the excision rates being influenced by the stereochemistry of lesions; specifically, the (6S,8R,11S) and (6S,8R,11R) isomers 6 and 8 were removed faster than the (6R,8S,11R) and (6R,8S,11S) isomers 7 and 9.

The removal of γ-OH-PdG 2, α-OH-PdG 3, and PdG 14 adducts was assayed in in vitro reactions using site specifically modified duplex oligodeoxynucleotides (69). Following incubation of these DNA substrates with a BER-competent HeLa cell extract, no products were detected that would be indicative of repair initiated by the BER glycosylases.

Thus, the data are consistent in demonstrating the necessity of NER, but not BER, for the efficient repair of enal-derived 1,N2-dG adducts. Interestingly, in contrast to these six-membered cyclic adducts, the five-membered unsaturated cyclic 1,N2-etheno-dG adduct is a substrate for E. coli mismatch-specific uracil DNA glycosylase and the human alkyl-N-purine DNA glycosylase (121). Additionally, it was observed that both acrolein and 4-HNE inhibited NER in human cells, suggesting the synergistic role of DNA adducts and protein damage in enal-induced carcinogenesis (27,122).

7. DNA−DNA Cross-Linking by Enal-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts

As noted, the aldehydes resulting from the ring opening of enal-induced 1,N2-dG lesions represent chemically reactive species within the minor groove of the DNA. DNA cross-linking was proposed based upon analysis of acrolein-treated DNA (58). The DNA interstrand cross-linking chemistry of the enal-mediated 1,N2-dG adducts was recently reviewed (51). It has been observed that γ-OH-PdG 2 could form reversible, interstrand DNA−DNA cross-links (Scheme 4) when placed in a 5′-CpG-3′ sequence context; no cross-link was observed in a GpC sequence (33). The cross-linked species was observed by HPLC and capillary gel electrophoresis and initially identified by mass spectrometry. The cross-linked dG nucleosides were identified from enzymatic digestion of the cross-linked duplex and fully characterized by independent chemical synthesis. Other 5′-CpG-3′ interstrand cross-links are known, for example, arising from mitomycin C (123,124) and nitrous acid (125). An N2-dG:N2-dG trimethylene linkage 23 (Scheme 4, R = H), a stable surrogate for the cross-link, was constructed in a self-complementary duplex that contained a 5′-GpC-3′ sequence; NMR analysis showed that its structure was distorted and its Tm was reduced (126,127), providing a rationale for why such a cross-link is not observed in a 5′-GpC-3′ sequence context. The native interstrand cross-links could potentially exist as equilibrium mixtures of carbinolamine 20, imine 21, or pyrimidopurinone 22 species (Scheme 4). The cross-links can be trapped by reduction with sodium borohydride or sodium cyanoborohydride, suggesting the presence of imine cross-link 21(33,128,129). The nature of γ-OH-PdG to dG interstrand cross-link was determined by NMR spectroscopy employing specific 15N and 13C labels; separate oligodeoxynucleotides were synthesized in which a 13C label was incorporated at the aldehyde carbon of the adduct and a 15N2-label of the unmodified dG of the complementary strand or an 15N2-label of the modified dG. A series of isotope-edited NMR experiments showed that the major cross-link species in duplex DNA was the carbinolamine 20, while the concentrations of the imine 21 and pyrimidopurinone 22 were below the level of detection (128,130,131).

A clue as to why the acrolein-derived cross-link preferred the carbinolamine 20(130,131) and not the pyrimidopurinone cross-link 22(128) was provided by an experiment in which an N2-dG:N2-dG trimethylene linkage 23 was constructed in a self-complementary duplex 5′-d(AGGCXCCT)2, where X represents the cross-linked dGs 23(127). The saturated linkage, which we believe is a reasonable model for the carbinolamine cross-link, caused minimal distortion of the duplex (127). Additionally, Tm studies monitored by NMR and modeling suggested that the carbinolamine linkage maintained Watson−Crick bonding at both of the cross-linked C·G pairs (131). Dehydration of carbinolamine 20 to imine 21, or cyclization of the latter to pyrimidopurinone linkage 22, would have disrupted Watson−Crick bonding at one or both of the cross-linked base pairs.

In addition to the formation of interstrand cross-links, the γ-OH-PdG adduct 2 was shown to form intrastrand cross-links (129). These were detected when the adduct was located 3′ next to the nick in the DNA, whereas a dG, dT, dA, or deoxyinosine was placed 5′ to the nick. Intra- vs interstrand cross-linking was distinguished by the electrophoretic mobilities of the products after sodium borohydride reduction. Because cross-links were formed even in the absence of readily identifiable reactive nucleophiles on the base across the nick, it seems plausible that the cross-linking occurred with other, more distant bases.

Interstrand cross-link formation of the crotonaldehyde and 4-HNE adducts was highly dependent upon adduct stereochemistry. After >20 days, ∼38% cross-link formation occurred for the (6R,8R)-crotonaldehyde adduct 4, whereas <5% cross-link was observed for the (6S,8S)-diastereomer 5(33). Isotope-edited NMR spectroscopy established that the carbinolamine form of the (6R,8R) cross-link was the only detectable cross-link species present in duplex DNA (35). NMR studies of the (6S,8S) diastereomer 5 at pH 9.3, which favor the ring-opened aldehyde, showed that the aldehydic group was oriented in the 3′ direction within the minor groove (35,132).

Structural studies utilizing saturated analogues of the (6R,8R)- and (6S,8S)-crotonaldehyde cross-links indicated that both retained Watson−Crick hydrogen bonds at the cross-linked base pairs (133). However, the (6S,8S)-diastereomer 5 showed lower stability. Whereas the CH3 group of the (6R,8R)-diastereomer 4 was positioned in the center of the minor groove, it was positioned in the 3′ direction for the (6S,8S)-diastereomer and interfered sterically with the DNA duplex structure (133). These results were consistent with modeling of the native cross-links (35).

Of the four 4-HNE adducts, only the one with the (6S,8R,11S) configuration formed an interstrand cross-link in the 5′-CpG-3′ sequence (34). The (6S,8R,11S) diastereomer 6 possesses the same relative C6 stereochemistry as the (6R,8R) crotonaldehyde adduct 4 (Figure 1), which also formed interstrand cross-links; these observations suggest that the adduct stereo chemistry is an important consideration in modulating interstrand cross-linking. Although cross-linking proceeded slowly, after 2 months, the yield was a remarkable ∼85%. The conformations of the cyclic hemiacetals corresponding to the (6S,8R,11S)- and (6R,8S,11R)-HNE-dG adducts 6 and 7 (Figure 5) were examined in a CpG sequence context (134). Both diastereomers were located within the minor groove of the duplex; the cyclic hemiacetal 27 derived from the (6S,8R,11S)-HNE adduct was oriented in the 5′ direction, while the cyclic hemiacetal 28 derived from the (6R,8S,11R)-HNE adduct was oriented in the 3′ direction. These differences in orientation suggest a structural basis that explains, in part, why the (6S,8R,11S)-diastereomer 6 forms interstrand cross-link in the 5′-CpG-3′ sequence, whereas the (6R,8S,11R)-diastereomer 7 does not. Spectroscopic studies to delineate the cross-linking chemistry of the HNE adducts are continuing.

8. Biological Processing of DNA−DNA Cross-Links Mediated by Enal-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts

DNA interstrand cross-links represent one of the most serious types of DNA damage, since fundamental biological processes, such as replication and transcription, require transitory separation of the complementary DNA strands. In higher eukaryotes, repair of interstrand cross-links requires the cooperation of multiple proteins that belong to different biological pathways, including, but not limited to, NER, homologous recombination, TLS, double-strand break repair, and the Fanconi anemia pathway (reviewed in refs (135−138)). A current model for interstrand cross-link repair suggests that this process is initiated by dual incision around the cross-link of one of the two affected strands. The dual incision, or “unhooking”, depends on NER in E. coli(139−142). In mammalian systems, various proteins have been suggested to be involved in this process and, in particular, the XPF/ERCC1 complex (143), a structure-specific endonuclease and a component of NER. The result of the dual incision is a gap that can subsequently be filled by either TLS or pairing of the 3′ end of the preincised strand with the homologous sequence, followed by DNA synthesis. In the former case, the complementary strand with the cross-link still attached is used as a template. Once the integrity of one DNA strand is restored, the second strand can be repaired by a conventional NER mechanism. When repair is concomitant with replication, a DNA double-strand break can be formed; thus, additional enzymatic activities are required to tolerate interstrand cross-links.

As discussed above, the enal-mediated DNA interstrand cross-links are chemically reversible. Consequently, the extent to which they are present in vivo and their potential to alter the biological processing of the enal-derived adducts remain to be determined. These problems represent an area of intense ongoing investigation. Studies to date have utilized the enal-mediated N2-dG:N2-dG interstrand cross-links as well as their chemically stable saturated analogues 23 as tools to address important questions on both molecular mechanisms of interstrand cross-link repair and biological consequences of this repair.

The saturated cross-link 23 (R = H) has been incorporated into a linear DNA fragment to investigate the processing of interstrand cross-links by the XPF/ERCC1 heterodimer (144). In the presence of RPA, XPF/ERCC1 acted as a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease; the progression of the exonuclease activity was attenuated at the cross-linked site. On the basis of this observation, the authors proposed a role for XPF/ERCC1 in the processing of a double-strand break that could be created when a cross-link encounters the replication fork.

Moriya and co-workers examined the repair of the crotonaldehyde-derived N2-dG:N2-dG interstrand cross-links following replication of site specifically modified vector DNAs in various E. coli and mammalian cells (145). The cross-links were positioned in a 5′-CpG-3′ sequence context. In a NER-deficient UvrA−E. coli mutant, vectors containing the stable, reduced cross-link 23 (Scheme 4, R = CH3) failed to yield transformants. Vectors adducted with the corresponding nonreduced cross-links did yield transformants under these conditions, suggesting that the native cross-links reverted at least partially to noncross-linked N2-dG lesions in the NER-deficient host. However, in NER-proficient E. coli, comparable numbers of transformants were obtained from either type of plasmid, regardless of whether the cross-link was reduced or not. This result confirmed the prior finding that NER is essential for repair of interstrand cross-links in E. coli(139,142). In human XPA cells, the reduced cross-link was removed, suggesting the presence of a repair pathway unique to higher eukaryotes that does not require the initial damage recognition by NER. This repair was not coupled with transcription but was associated with replication. On the basis of recovery of progeny DNAs from wild-type cells and XPA cells, the authors concluded that although the NER-independent pathway significantly contributed to the repair, NER still played a major role. The analyses of recovered DNA molecules revealed that the native and reduced cross-links were modestly miscoding (6% of mutations or less) in both E. coli and mammalian cells, with G→T transversions predominating. The cross-linked dG located in the lagging strand was the primary site of mutations. These observations are consistent with a model for interstrand cross-link repair by a recombination-independent pathway and provide important information regarding the initiating steps of this process. The authors’ interpretation of the data was that in human cells, NER is acting to “unhook” strands on nonreplicating DNA, while at the replication fork, incisions around the cross-link can be generated by a structure-specific endonuclease, for example, XPF/ERCC1, independently of NER. This is an interesting idea that requires further validation.

Using site specifically modified vector DNAs, the fidelity of recombination-independent repair was also assessed for the reduced acrolein-mediated N2-dG:N2-dG interstrand cross-link 23 (Scheme 4, R = H). Replication of DNAs containing this lesion was accurate in ∼97% of bypass events in COS-7 cells (146). G→T transversions were the only mutations detected when the cross-link was positioned in a CpG sequence, a result that is in agreement with data on mutagenic properties of the crotonaldehyde-mediated cross-links (145). Interestingly, the same acrolein-mediated cross-link in a GpC sequence context caused predominantly short deletions (<15 nucleotides) and G→A transitions. In wild-type E. coli, no mutations were found in 52 analyzed DNA clones that originated from vectors containing acrolein-mediated cross-link 23 in the CpG sequence (147). Thus, in both bacterial and mammalian systems, stable analogues of the acrolein- and crotonaldehyde-mediated N2-dG:N2-dG interstrand (23) cross-links are processed by a recombination-independent mechanism in a largely error-free manner.

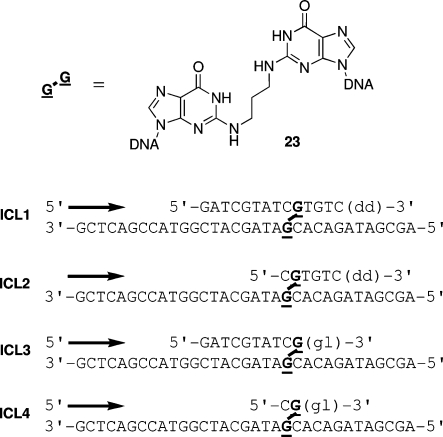

In TLS-dependent repair of interstrand cross-links, these pols are recruited presumably to carry out gap-filling replication through the cross-link site. On the basis of a number of observations, Rev1 and pol ζ have been proposed to conduct this reaction in eukaryotes. Indeed, deficiency in either of these activities confers hypersensitivity to DNA cross-linking agents (148−150) and results in less efficient but more accurate cellular processing of interstrand cross-links (151). However, until very recently, no biochemical data have existed showing the abilities of Rev1 and pol ζ to bypass aberrant DNA structures that could be formed as intermediates in the interstrand cross-link repair. With synthetic chemical strategies for the construction of oligodeoxynucleotides containing the reduced acrolein-mediated N2-dG:N2-dG interstrand cross-links, we prepared a series of DNA substrates that mimic potential repair intermediates (ICL1-ICL4, Figure 3) and examined the abilities of various DNA pols to replicate past the cross-linked sites (146). The data revealed that yeast Rev1 was quite efficient at inserting the correct nucleotide, dC, opposite the cross-linked dG in ICL4 but, as expected, could not carry out DNA synthesis beyond this site. Yeast pol ζ was incapable of nucleotide incorporation opposite the cross-linked dG in any of the DNA substrates examined, and it was strongly inhibited at the extension step. In the presence of Rev1, which is known to stimulate pol ζ activity (152), pol ζ inefficiently extended primers containing the mismatched terminal nucleotides opposite the cross-linked dG; extension from the correctly paired dC was barely detectable. Although the data are consistent with the proposed role for Rev1 in TLS past interstrand cross-links, no evidence was found showing an ability of pol ζ to catalyze this reaction. Given the cellular role for pol ζ in recombination-independent repair of mitomycin C-induced cross-links (151) and the structural similarity between mitomycin C-induced cross-links and interstrand cross-links that were used in replication assays in vitro (stable analogues of the acrolein-mediated N2-dG:N2-dG cross-link in a CpG sequence context), the latter observation is surprising. Thus, the possibility should be considered that the major function of pol ζ in TLS past N2-dG:N2-dG interstrand cross-links is not DNA synthesis per se but rather facilitation of this process. For example, this might occur by recruiting other TLS pols or scaffolding the TLS machinery.

Figure 3.

Oligodeoxynucleotides containing the reduced acrolein-mediated N2-dG:N2-dG interstrand cross-link (23).

In contrast to pol ζ, human pol κ not only catalyzed accurate incorporation opposite the cross-linked dG but also replicated beyond the lesion (146). The efficiency of the bypass reaction was significantly enhanced by truncation of the 3′ end of the nontemplate strand (ICL3, Figure 3), and it was further enhanced by truncation of the 5′ end (ICL4, Figure 3). Steady-state kinetic parameters were measured for ICL4; relative to the nondamaged dG, the efficiency of dC incorporation opposite the cross-linked dG was reduced ∼35-fold, whereas the efficiency of extension from dC opposite the lesion was reduced ∼7-fold. E. coli pol IV, an orthologue of human pol κ, could carry out the same bypass reaction on DNA templates containing the reduced acrolein-mediated N2-dG interstrand cross-links as well (147). The efficiency of dC incorporation opposite the cross-linked dG in ICL4 was reduced ∼50-fold relative to that observed for the nondamaged dG, and the extension efficiency from dC opposite the lesion was reduced ∼2-fold. E. coli pol II was unable to catalyze TLS past these cross-links (147).

The reduced acrolein-mediated N2-dG:N2-dG interstrand cross-link was site specifically incorporated into a DNA vector, and this modified vector was utilized to transform wild-type E. coli strain and pol II and pol IV deletion mutants (147). Whereas the transformation efficiency of a pol II-deficient strain was indistinguishable from that of the wild type, the ability to replicate the modified DNA was nearly abolished in a pol IV-deficient strain. Furthermore, following exposure to mitomycin C, both the pol IV-deficient E. coli and the pol κ-depleted human fibroblasts cells showed decreased survival relative to corresponding controls (146,147). In addition, the extent of chromosomal aberrations was significantly elevated in pol κ-depleted vs control fibroblasts following mitomycin C treatment (146). Combined, these data strongly suggest that DNA pols of the DinB family, E. coli pol IV and human pol κ, are key components of TLS-assisted repair of N2-dG:N2-dG interstrand cross-links.

Overall, the recent progress in developing chemical strategies to synthesize the enal-mediated interstrand cross-link models made investigations into the biology of these lesions using site-specific approaches possible. Site specifically modified oligodeoxynucleotides containing enal-mediated interstrand cross-links have been proven to be an indispensable tool that not only allowed the validation of existing models for interstrand cross-link repair but also led to the discovery of new functions of the previously known enzymatic activities and the formulation of further hypotheses.

Chemically stable intrastrand cross-links were also utilized as tools in biochemical investigations. The reduced cross-link model of the acrolein-derived intrastrand cross-link 23 (R = H) was examined in replication assays in vitro with E. coli pols I, II, and III (153). Primer extension experiments showed major blockage of all three pols one nucleotide prior to the first dG of the cross-link; only pol I was able to incorporate a nucleotide opposite the first dG with no incorporation being detected opposite the second cross-linked dG. The intrastrand cross-link 23 was shown to be a substrate for the E. coli UvrABC NER complex (153). The extent of incision of this three-carbon cross-link was significantly less than that observed for the more structurally perturbed two-carbon cross-link (153).

9. DNA−Protein Conjugation Mediated by Enal-Derived 1,N2-Deoxyguanosine Adducts