Summary

The neural crest is induced by a combination of secreted signals. Although previous models of neural crest induction have proposed a step-wise activation of these signals, the actual spatial and temporal requirement has not been analysed. Through analysing the role of the mesoderm we show for the first time that specification of neural crest requires two temporally and chemically different steps: first, an induction at the gastrula stage dependent on signals arising from the dorsolateral mesoderm; and second, a maintenance step at the neurula stage dependent on signals from tissues adjacent to the neural crest. By performing tissue recombination experiments and using specific inhibitors of different inductive signals, we show that the first inductive step requires Wnt activation and BMP inhibition, whereas the later maintenance step requires activation of both pathways. This change in BMP necessity from BMP inhibition at gastrula to BMP activation at neurula stages is further supported by the dynamic expression of BMP4 and its antagonists, and is confirmed by direct measurements of BMP activity in the neural crest cells. The differential requirements of BMP activity allow us to propose an explanation for apparently discrepant results between chick and frog experiments. The demonstration that Wnt signals are required for neural crest induction by mesoderm solves an additional long-standing controversy. Finally, our results emphasise the importance of considering the order of exposure to signals during an inductive event.

Keywords: Neural crest induction, Mesoderm, Wnt, BMP, Slug, Sox2

INTRODUCTION

The neural crest (NC) is a cell population characteristic of vertebrates that gives rise to a variety of cell types, including neurons and glia in the peripheral nervous system, connective tissues of the craniofacial structures and pigment cells of the skin (LeDouarin and Kalcheim, 1999). This population is induced at the neural plate border by interactions between the neural plate and nearby tissues (Moury and Jacobson, 1990; Selleck and Bronner-Fraser, 1995; Mancilla and Mayor, 1996; Mayor et al., 1997). From studies in chick, amphibian and zebrafish embryos, some of the signals involved in the induction of the NC have been identified, including BMPs, Wnts, FGF, Notch and RA (reviewed by Basch et al., 2004; Steventon et al., 2005).

Although the role of Wnt as a NC inducer has been clearly demonstrated in different animal models (reviewed by Wu et al., 2003; Heeg-Truesdell and LaBonne, 2006), the participation of BMPs as an inducer has been more controversial. Experiments in Xenopus and zebrafish show that an inhibition of BMP is required for NC induction, whereas experiments in chick indicate that activation of BMP is sufficient to induce NC (Liem et al., 1995; Marchant et al., 1998; Nguyen et al., 1998; LaBonne and Bronner-Fraser, 1998; Endo et al., 2002). The multitude of signalling molecules involved in NC induction has generated the idea that NC induction is a multi-step process, with the different signals acting at different steps during the inductive process; however, the precise temporal requirement for these signals has not yet been determined.

NC induction is thought to occur through the complex movements of gastrulation and neurulation, and hence the prospective NC is likely to encounter signals from a variety of sources. Several studies have shown that mesoderm is able to induce NC (Raven and Kloos, 1945; Bonstein et al., 1998; Marchant et al., 1998; Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003), but the exact nature of the signals produced by the mesoderm is unknown. The role of Wnt signalling during NC induction by mesoderm has been controversial. It has been shown that Wnt signals are required for NC induction and that some Wnt ligands are expressed in the mesoderm, but specific inhibition of Wnt signals produced by the mesoderm does not affect NC induction, suggesting that NC induction by mesoderm is Wnt independent (Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003). Moreover, a recent report has clearly shown that FGF acts in a Wnt-dependent manner during the early stages of NC induction towards the end of gastrulation (Hong et al., 2008). It is of importance now to reconcile these results directly with those of Monsoro-Burq et al. (Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003).

To understand better the spatial relation of the mesoderm to the prospective NC, we performed the first fate map of this tissue at gastrula stages. We found that a specific region of the prospective mesoderm (dorsolateral marginal zone, DLMZ) is adjacent to the NC during its induction at the gastrula stage. As gastrulation and neurulation proceed, the DLMZ differentiates into primarily intermediate mesoderm (IM) and moves to become directly underneath the NC at the neurula stage. We show for the first time that induction of NC requires two steps: first, signals from the DLMZ participate in its early induction during gastrulation, and then signals from the IM underlying the NC and adjacent ectodermal tissue are involved in maintenance of the NC identity during neurulation. We demonstrate that Wnt activity is needed for both steps, whereas BMP activity is differentially required between the early and late step of NC induction. The first inductive step requires BMP inhibition, but the second maintenance step requires BMP activation. These results allow us to propose a new two step model for NC induction and to explain the discrepancies in the BMP requirement between chick and Xenopus embryos.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Xenopus embryos, micromanipulation and whole-mount in situ hybridisation

Xenopus embryos were obtained as described previously (Gómez-Skarmeta et al., 1998) and staged according to Nieuwkoop and Faber (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967). Dissections and grafts were performed as described by Mancilla and Mayor (Mancilla and Mayor, 1996). In situ hybridisation was performed as described by Harland (Harland, 1991). The genes analysed were Snail2 (formerly Slug) (Mayor et al., 1995), Foxd3 (Sasai et al., 2001), Wnt8 (Christian and Moon, 1993), Sox2 (Kishi et al., 2000), Chordin (Sasai et al., 1994) and BMP4 (Wardle et al., 1999).

DiI injections and construction of fate map

Injections of DiI (Molecular Probes) were performed at stage 10 as described by Linker et al. (Linker et al., 2000). Photos were taken immediately, at stages 11.5, 13, 17, and at stage 28. Embryos were sectioned at stage 28 and based on their locations and previous positions, the fate of each label was assigned. Each label was then mapped onto a representative stage 10 embryo by counting cells from the blastopore lip.

RNA synthesis in vitro and microinjection of mRNAs or morpholino oligonucleotides

All plasmids were linearised and RNA transcribed as described by Harland and Weintraub (Harland and Weintraub, 1985). RNA was co-injected with FLDx (Molecular Probes) as described by Aybar et al. (Aybar et al., 2003); or with 200-600 pg of nuclear lacZ mRNA (kind gift from Ali H. Brivanlou). The constructs used were: dd2 (Sokol, 1996); dnTCF3 (Molenaar et al., 1996; Hamilton et al., 2001); Wnt8 (Sokol, 1996); dnWnt8 (Hoppler et al., 1996); β-catenin-GR (Domingos et al., 2001); Smad7GR (Wawersik et al., 2005); and GSK3-pCS2 (Shimizu et al., 2000). A 1 mM mixture of two different chordin morpholino oligonucleotides (Oelgeschlager et al., 2003) was injected into the dorsolateral equatorial region of a two-cell embryo. Treatment with dexamethasone was performed as described previously (Tribulo et al., 2003).

Protein and chemical inhibitor treatment

For proteins, heparin acrylic beads (Sigma) were soaked overnight in 40 μg/ml Dkk1 (Calbiochem), 50 μg/ml Noggin (R&D Systems) or 20 μg/ml BMP4 (R&D Systems) all suspended in 0.1% BSA. Beads were grafted into explants/whole embryos for entire culture period prior to fixation.

Luciferase assay

Embryos were injected four times at the two-cell stage with 25 pg TOPflash or Vent1-luciferase DNA. Explants or whole embryos were then taken and homogenised as described below. Whole embryo readings were taken with each explant experiment as a further positive control. For each sample, 15-20 explants were taken and homogenised immediately in 25 μl 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), centrifuged and a further 25 μl Tris was added to the supernatant. The volume was brought up to 250 μl with the reporter lysis buffer provided with a luciferase assay kit (Promega). The samples were then freeze-thawed and the luciferase activity measured as per manufacturers instructions on a single-tube luminometer (Turner BioSystems). Each reading was standardised by protein concentration as determined by absorbance at 280 nm. Readings were further normalised to control injections of FOPflash that contains a mutated version of the Wnt responsive promoter.

RESULTS

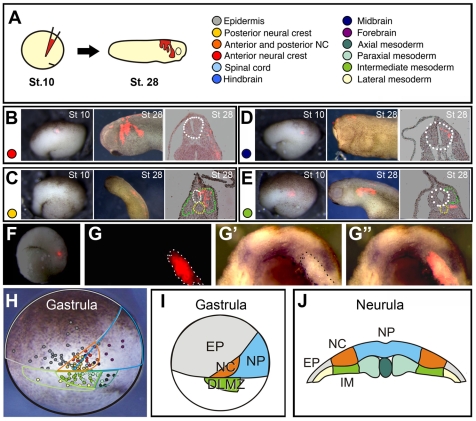

NC fate map

To locate the prospective NC region, we applied small injections of the lipophilic dye DiI to deep ectodermal cells of stage 10 embryos (Fig. 1A) to mark groups of 10-20 cells; the fate of these labelled cells was analysed at successive time-points until stage 28 (for examples see Fig. 1B-E). On the basis of these data, a stage 10 fate map showing the position of the prospective NC cells and mesoderm was constructed (Fig. 1H,I). It can be clearly seen from this fate map that at stage 10 the prospective NC population lies adjacent to the DLMZ. Labels within the DLMZ itself were fated to become predominantly intermediate mesoderm, which lies beneath the NC at neurula stage (IM, an example is shown in Fig. 1F-G). In situ hybridisation against Snail2 in these embryos shows that intermediate mesoderm labelled with DiI underlies the NC cells (Fig. 1G-G″). A summary of the gastrula and neurula fate map is shown in Fig. 1I,J, which shows that DLMZ at the gastrula stage and IM at the neurula stage are adjacent to the NC. The location of the DLMZ supports its involvement in early NC induction and our fate map opens the possibility that IM could play a role in later NC development.

Fig. 1.

NC fate map. (A) Stage 10 embryos were injected with small quantities of the lipophilic marker DiI to label prospective neural crest cells and the surrounding tissues. (B-E) Representative examples of the labelled cells contributing to the cephalic NC (B), trunk NC (C), midbrain (D) and posterior intermediate mesoderm (E). Broken lines outline the neural tube (white), notochord (yellow) and somites (green). (F,G) DLMZ becomes IM and underlies the NC. (F) DiI was used to label the DLMZ of a stage 10 embryo. At the neurula stage (stage 16), the embryos were fixed and in situ hybridisation against Snail2 was performed. (G) Section showing fluorescence in the IM. (G′) Same section as in G showing Snail2 expression (G″) Merge of G and G′. (H) The position of each labelled cell was mapped onto a photo of a stage 10 embryo. Each colour corresponds to the key shown in A. (I) A summary of fate map at stage gastrula stage. (J) Summary of the position of NC in relation to IM at the neurula stage.

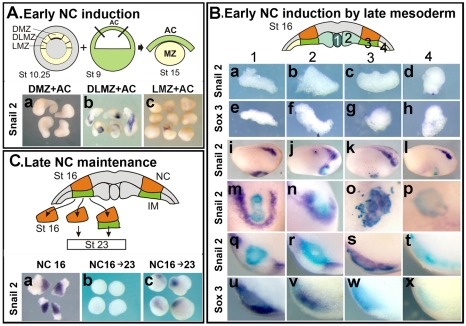

Two steps of NC specification: induction by DLMZ and maintenance by IM

To test the inductive ability of DLMZ and IM, tissue recombination assays were performed. Although the inductive abilities of the DLMZ have been already reported (Bonstein et al., 1998; Marchant et al., 1998; Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003), we include here the DLMZ assay to compare it with the induction by IM. The entire marginal zone of stage 10.25 embryos was dissected and divided into dorsal (DMZ, the region above the blastopore lip), dorsolateral (DLMZ, the region next to the blastopore lip) and lateral (LMZ, the next region that is not adjacent to the blastopore lip); these explants were conjugated with stage 9 animal caps, and the expression of the NC markers Snail2 and FoxD3 was analysed at the equivalent of stage 15 (Fig. 2A). Both genes are expressed in a similar manner; thus, for simplicity, only the expression of Snail2 is shown. Only DLMZ, but not DMZ or LMZ, was able to induce NC markers (Fig. 2A, parts a-c; Snail2: 85%, n=69; FoxD3: 80%, n=44). These results show that DLMZ is involved in NC induction at the gastrula stage, confirming previous reports (Bonstein et al., 1998; Marchant et al., 1998; Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003).

Fig. 2.

NC induction by DLMZ and IM. (A) Early NC induction. The prospective mesoderm was dissected out from stage 10.25 embryos and divided in dorsal marginal zone (DMZ), dorsolateral marginal zone (DLMZ) and lateral marginal zone (LMZ). This tissue was then conjugated with an animal cap taken from a stage 9 embryo and cultured until the equivalent of stage 15 when the expression of the NC marker Snail2 was analysed. (a) Conjugates with DMZ. (b) Conjugates with DLMZ. (c) Conjugates with LMZ. (B) Early NC induction by late mesoderm. Different regions of mesoderm (named 1-4) were dissected from a stage 16 neurula embryo previously injected with FDX and grafted into the blastocoel cavity of a stage 10 gastrula embryo. The grafted embryos were cultured until stage 16 when the expression of Snail2 and Sox3 was analysed. (a-h) Control explants of mesoderm were fixed immediately to analyse the expression of Snail2 and Sox3; no expression of these markers was observed. Purple, in situ hybridisation; blue, grafted tissue. (i-l) Lateral view of grafted embryos showing expression of Snail2. Dorsal is towards the top; anterior towards the right. Only embryos in which the grafted tissue was located in ventral epidermis were analysed. (m-p) Higher magnification of the graft showing expression of Snail2. (q-t) Section through the graft showing expression of Snail2. (u-x) Section through the graft showing expression of Sox3. (C) Late NC maintenance. NC explants were dissected from a stage 16 neurula embryo; NC was fixed immediately or cultured alone or together with the underlying IM until the equivalent of stage 23. The expression of Snail2 was analysed. (a) NC dissected from a stage 16 embryo and fixed immediately. (b) NC cultured until the equivalent of stage 23. (c) NC cultured with the underlying mesoderm (IM).

The role of IM was tested in two different assays. First, explants of different regions of underlying mesoderm were taken from a stage 16 neurula and grafted into the blastocoels cavity of stage 10 embryos (Fig. 2B). Region 1 represents the axial most mesoderm, the notochord. Regions 2, 3 and 4 correspond to predominantly paraxial, intermediate and lateral mesoderm, respectively. Embryos were fixed at stage 16 and analysed for the expression of NC (Snail2) and neural plate markers (Sox3), and for the lineage tracer (FDX) to identify the grafted tissue. Mesodermal explants do not express neural plate or NC markers (Fig. 2B, parts a-h, n=7-10 with 0% expressing markers in all cases). Regions 1, 2 and 3 were able to induce NC markers in ventral epidermis (Fig. 2B, parts i-k), whereas region 4 was not inductive (Fig. 2Bl, parts p, t, x). However, regions 1 and 2 induced NC at a distance (Fig. 2B, parts m, n, q, r), whereas region 3 induced Snail2 in the adjacent cells (Fig. 2B, parts o, s), suggesting that IM was a direct NC inducer. This idea was supported by the observation that whereas the two most axial regions (1 and 2) of mesoderm induced NC and neural plate markers (Fig. 2B, parts u, v), region 3 induced NC without neural plate (Fig. 2B, part w). This is the region of mesoderm that underlies the NC, is the main derivative of the DLMZ (Fig. 1F,G) and corresponds to the intermediate mesoderm (IM), as judged in sections (Fig. 1E). Although this experiment indicates that the IM has the ability to induce NC directly in gastrula ectoderm, it does not prove that it plays a similar inductive role in normal development. To test the requirement of IM in NC specification, NC from 16 neurula embryos were dissected and cultured in isolation, in the presence or absence of IM (Fig. 2C). NC isolated at stage 16 and fixed immediately express the NC markers Snail2 and Foxd3 (Fig. 2C, part a; Snail2: 100%, n=20; Foxd3: 100%, n=15), indicating that NC induction has already taken place. However, if the NC is cultured in isolation until the equivalent of stage 23, the expression of the NC markers is completely lost (Fig. 2C, part b, 2% of Snail2 expression, n=20; 0% of Foxd3 expression, n=10), suggesting that some additional signals are still required to maintain the induced NC. Interestingly, if an equivalent culture of NC is performed but now with the adjacent IM, the expression of the NC markers Snail2 and Foxd3 is maintained (Fig. 2Cc; 65%, n=19 for Snail2; 68%, n=12 for Foxd3).

Taken together, these results show that DLMZ is able to induce NC in the ectoderm of the early gastrula and that IM is required for the maintenance of the induced NC at the neurula stage. Do these two steps of NC specification require the same set of signals?

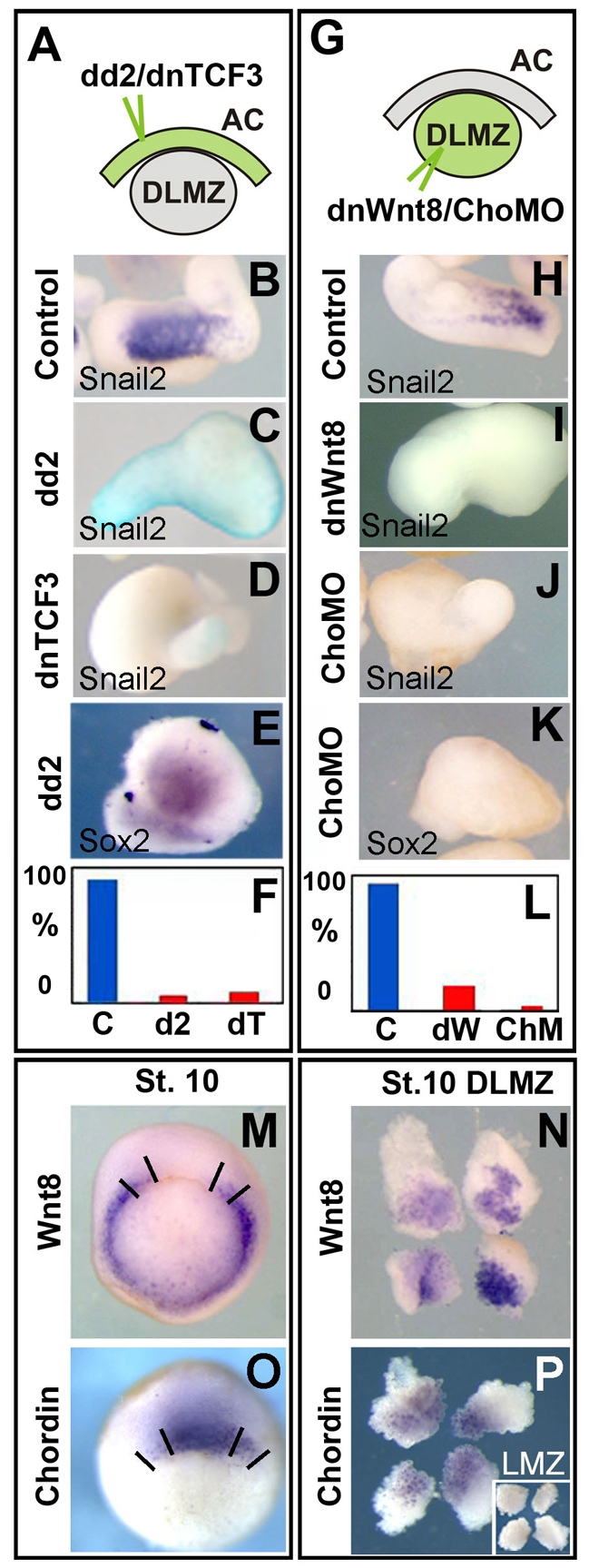

Activation of Wnt and inhibition of BMP are required for NC induction by the DLMZ

To test whether the DLMZ uses Wnt signals to induce the NC, we first blocked this pathway in the ectoderm in a cell-autonomous manner (Fig. 3A). Animal caps were injected with the specific Dishevelled (Dsh) mutant (dd2) (Sokol, 1996), or the dominant-negative form of the TCF3 protein (Hamilton et al., 2001), both potent intracellular Wnt inhibitors. No Snail2 expression was observed in either control animal caps or animal caps injected with either of these constructs. Control conjugates of animal caps and DLMZ presented a strong induction of NC markers (Fig. 3B,F), which was almost completely inhibited by injection of dd2 or dnTCF3 mRNAs in the animal cap (Fig. 3C,D,F). These results suggest that activation of the canonical Wnt pathway in the ectoderm is necessary for NC induction by DLMZ.

Fig. 3.

Early Induction of the NC by DLMZ requires Wnt activation and BMP inhibition. (A-F) The DLMZ was dissected from stage 10.5 embryos and conjugated with animal caps taken from embryos injected at the eight-cell stage with 1 ng of dd2 or 0.6 ng of dnTCF3 mRNA together with FLDx. The conjugates were cultured until the equivalent of stage 15 and the expression of Snail2 (B-D) or Sox2 (E) was analysed. (B) Control conjugate of DLMZ with uninjected animal cap. (C) Conjugate of DLMZ with an animal cap injected with dd2 mRNA. (D) Conjugate of DLMZ with animal cap injected with dnTCF3 mRNA. (E) Sox2 expression showing continued presence of neural plate (68%, n=19). FDX injected animal caps also express Sox2 (data not shown, 63%, n=11). (F) Summary of the expression of Snail2 in conjugates. Each experiment was repeated three times with at least 26 explants each. (G-L) The DLMZ was dissected from stage 10.5 embryos injected at the eight-cell stage in the equatorial region with 1 ng of dnWNT8 mRNA or 2 ng of morpholinos against chordin (cho MO), and conjugated with animal caps taken from uninjected embryos. The conjugates were cultured until the equivalent of stage 15 and the expression of Snail2 (H-J) or Sox2 (K) was analysed. (H) Control conjugate. (I) Conjugate containing DLMZ injected with dnWnt8 mRNA. (J) Conjugate containing DLMZ injected with cho MO. (K) Sox2 expression showing inhibition of neural plate by cho MO (0% of expression, n=30), when compared with controls (75% of expression, n=20; not shown). (L) Summary of the expression of Snail2 in conjugates. Each experiment was repeated three times with at least 30 explants each. (M,N) In situ hybridisation of Wnt8 in a stage 10.25 gastrula (M) or in DLMZ (N). (O,P) In situ hybridisation of chordin in a stage 10.25 gastrula (O) or in DLMZ (P); inset in N shows LMZ. Lines in M and O indicate how the DLMZ was dissected.

To test whether Wnt and anti-BMP signals are produced by the DLMZ for induction of NC cells, a specific inhibition in the mesoderm was performed (Fig. 3G). Conjugates of normal animal caps with DLMZ taken from embryos previously injected with a dominant-negative form of Wnt8 (dnWnt8) or a mixture of morpholinos against the BMP inhibitor chordin (cho MO) (Oelgeschlager et al., 2003) were performed. Snail2 expression in control conjugates (Fig. 3H,L) was almost completely abolished by the injection of dnWnt8 or cho MO in the DLMZ (Fig. 3I,J,L). As expected, an inhibition of chordin, but not of Wnt, signalling resulted in an inhibition of the neural plate marker Sox2 (Fig. 3E,K).

Are these molecules expressed in the DLMZ at the early gastrula stages? In situ hybridisation against Wnt8 and chordin in whole embryos or in dissected DLMZ shows a clear co-expression in the DLMZ (Fig. 3M-P). Taken together, these results indicate that Wnt signalling and anti-BMP molecules, such as chordin, are required for NC induction by DLMZ.

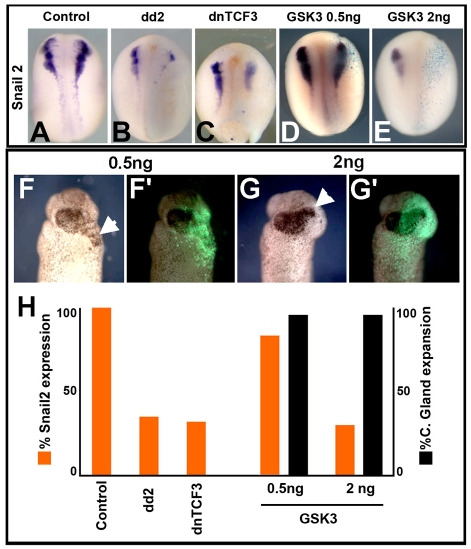

It has been published, in apparently similar experiments, that NC induction by DLMZ requires FGF while Wnt signalling is dispensable (Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003). In order to understand this apparent discrepancy, we proceeded to repeat some of these experiments and compare them with our experiments. It is known that inhibition of Wnt signalling can anteriorise the neural plate and later increase cement gland formation (Deardorff et al., 1998; Kiecker and Niehrs, 2001). In the Monsoro-Burq study (Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003), the expansion of the cement gland was used as a positive control to check the Wnt inhibitor treatments without a direct analysis of the effect on NC markers in whole embryos. This leaves open the possibility that expansion of cement gland and inhibition of NC have different sensitivities to the Wnt inhibitor treatments and could explain the differences in these results. To test this possibility, we compared the capacity of the Wnt inhibitor GSK3 (used by Monsoro-Burq et al.), to expand cement gland and to inhibit Snail2. We observed that injection of 0.5 ng of GSK3 mRNA produced a strong expansion in cement gland (Fig. 4F,F′; black bar in Fig. 4H) but did not inhibit Snail2 expression (Fig. 4D,H); only extremely high concentrations of GSK3 mRNA, higher than those used by Monsoro-Burq et al., were able to block NC induction efficiently (Fig. 4E,H) and expand the cement gland (Fig. 4G,G′,H). These results show that expansion of cement gland occurs under a mild Wnt inhibition, whereas a more complete inhibition of Wnt signaling is require to abrogate induction of NC. We next showed that the Wnt inhibitors dd2 and dnTCF3 are able to inhibit NC markers in whole embryo under the conditions used in our conjugates experiments (Fig. 4A-C,H). These results indicate that the conditions used by Monsoro-Burq et al. (Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003) were not sufficient to inhibit NC induction.

Fig. 4.

NC and cement gland have different sensitivity to Wnt inhibition. Embryos were injected at the eight-cell stage embryo with the indicated mRNA, fixed between stages 16-18 when the expression of Snail2 was analysed. Right side of the embryo corresponds to the injected side. (A) Control embryo. (B) Embryo injected with 1 ng of dd2 mRNA. (C) Embryo injected with 0.6 ng of dnTCF3. (D) Embryo injected with 0.5 ng of GSK3 mRNA. (E) Embryo injected with 2 ng of GSK3 mRNA. (F) Embryo injected with 0.5 ng GSK3 mRNA showing cement gland expansion (arrowhead); (F′) fluorescence overlay showing site of injection. (G) Embryo injected with 2 ng GSK3 showing cement gland expansion (arrow); (G′) fluorescence overlay showing site of injection. (H) Summary of the results in whole embryos. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

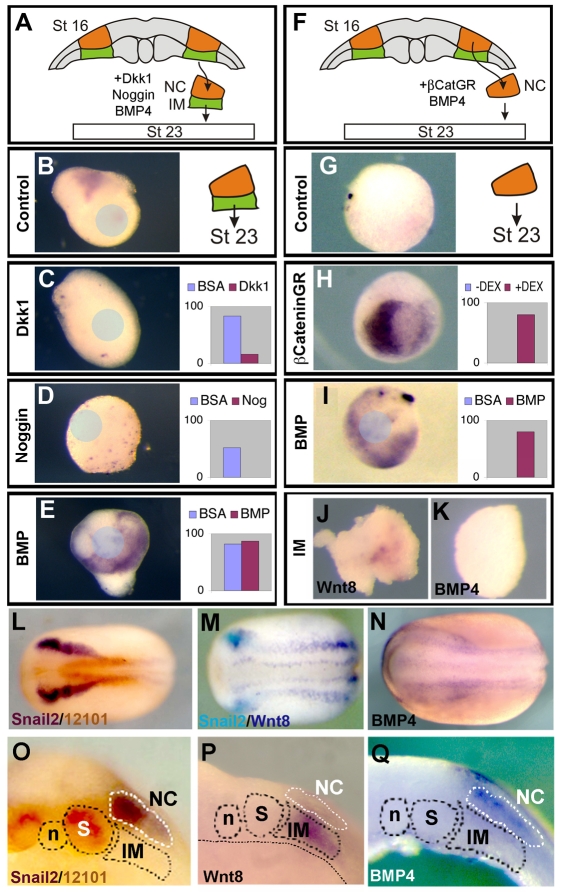

Activation of Wnt and BMP signalling is required for NC maintenance

We then examined the signals involved in the NC maintenance step (Fig. 2C). Explants of NC and underlying mesoderm (NC/M) dissected at stage 16, were cultured in the presence of Wnt and BMP inhibitors until the equivalent of stage 23 (Fig. 5A). Inhibitors were immobilised into beads that are embedded into the explant. The beads are about one-third of the size of the explant, and thus we assume that most, if not all, of the cells receive the signal. Control conjugates express the NC marker Snail2 (Fig. 5B), whereas its expression was blocked by treatment with the Wnt inhibitor dkk1 (Fig. 5C), suggesting Wnt signaling is also required for NC maintenance. Further support for this possibility comes from the finding that β-catenin activation in isolated NC explants is able to maintain Snail2 expression (Fig. 5H), which is otherwise lost (Fig. 5F,G). Treatment with Noggin, an endogenous BMP inhibitor, resulted in an inhibition of Snail2 expression (Fig. 5D), suggesting that BMP is required for NC maintenance. Accordingly, culturing the NC/M explants in the presence of BMP4 did not inhibit Snail2 expression (Fig. 5E). In addition, isolated NC explants cultured (Fig. 5F) in the presence of BMP4 resulted in maintenance of Snail2 expression (Fig. 5I). Overall, these results show that during the maintenance step at the neurula stage activation of both Wnt and BMP signals is required. Subsequently, we found that at the neurula stage Wnt8 and BMP4 are expressed in tissues surrounding the NC (Fig. 5L-N). Specifically, we found that IM express Wnt8, whereas BMP4 is expressed in the ectoderm adjacent and in the NC (Fig. 5O-Q). That the IM expresses Wnt8 but not BMP4 was further confirmed by direct analysis of these genes in isolated mesoderm (Fig. 5J,K).

Fig. 5.

NC maintenance requires activation of Wnt and BMP. (A-E) Explants of the NC and underlying intermediate mesoderm were taken at stage 16, cultured until sibling embryos were at stage 23 and analysed for the expression of the NC marker Snail2. Position of beads is indicated by the blue circle. (A) Diagram of experiments shown in B-E. (B) Control explant cultured in the presence of BSA-soaked bead. (C-E) Explant cultured in the presence of beads soaked with Dkk1 (C), Noggin (D), BMP4 (E). (F-I) Explant of the NC alone were taken at stage 16 and cultured until sibling embryos were at stage 23, then analysed for expression of Snail2. (F) Diagram of experiments shown in G-I. (G) Control explant. (H) Explant from embryos previously injected with β-cateninGR were cultured with or without dexamethasone. (I) Explant cultured in the presence of BMP. For each condition, the percentage of conjugates expressing Snail2 is summarised in the graphs. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. (J,K) IM was dissected from stage 16 embryos and the expression of Wnt8 (J) and BMP4 (K) was analysed. (L-Q) Analysis of NC markers and inducers in stage 16-18 neurula embryos as indicated. (L) Double stating against Snail2 and 12-101 antigen (a muscle specific monoclonal antibody) (Kintner and Brockes, 1984). (M) Double in situ hybridisation against Snail2 and Wnt8. (N) BMP4 expression. (O-Q) Sections of equivalent embryos to those shown in L-N. n, notochord; S, somites; IM, intermediate mesoderm; NC, neural crest. (O) Snail2/12-101 staining showing that it is the IM and not the somite the tissue that underlay the NC. (P) Wnt8 is expressed in the IM. (Q) BMP4 is expressed in the ectoderm next to or within the NC.

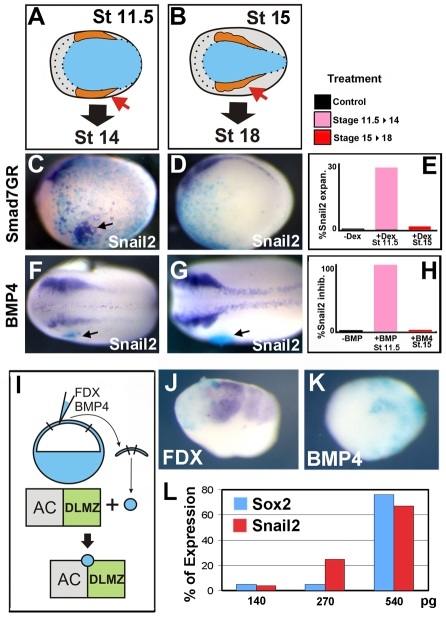

We tested the observed change in BMP necessity in whole embryos by analysing the expression of NC markers after performing the same activation or inhibition of BMP activity at the gastrula or neurula stage (Fig. 6A,B). In order to inhibit BMP signal in the whole embryo, we injected an inducible Smad7 construct (Wawersik et al., 2005) into blastomeres fated to differentiate as ventral epidermis. Inhibition of BMP signaling in the ventral epidermis can induce Snail2 expression during gastrulation (Fig. 6C,E) but not thereafter (Fig. 6D,E). No induction was observed in the absence of dexamethosone (Fig. 6E). The amount of Smad7 used in this experiment was able to induce specifically NC with little or no neural plate induction (Fig. 6L). It is known that the epidermis loses competence for NC induction from stage 13 onwards (Mancilla and Mayor, 1996), and hence the observed changes in response to Smad7GR might be due to a change in competence. We next performed the opposite experiment by adding BMP4 to the embryos. Animal cap cells that had been previously injected with high levels of BMP4 mRNA were grafted adjacent to the NC and the expression of NC markers was analysed. As a control to ensure that the injected animal cap cells are expressing BMP4 at high levels, they were conjugated with explants of DLMZ and animal cap (Fig. 6I-K). When conjugated with cells injected with FDX only, an induction of Snail2 is observed (Fig. 6J), whereas when conjugated with cells injected with FDX/BMP4, an inhibition of Snail2 induction is observed (Fig. 6K), indicating that the injected cells produce enough BMP4 to inhibit NC induction. BMP4-expressing cells grafted into gastrula embryos inhibit Snail2 expression (Fig. 6F,H). However, Snail2 expression is not affected if the same graft is performed at neurula stages during the maintenance step (Fig. 6G,H). Graft of control cells did not affect the NC at the gastrula or neural stages (Fig. 6H). Together, these results confirm our previous results obtained in explants and show that a change in BMP activity is required between the induction and the maintenance steps.

Fig. 6.

Distinct temporal requirements for signals during NC development in vivo. (A,C,F) Embryos were manipulated just prior to Snail2 expression at stage 11.5 then analysed at stage 14, to determine the period of NC induction. (B,D,G) Embryos manipulated at stage 15, after Snail2 expression has started, and analysed at stage 18 prior to NC migration, to determine the NC maintenance period. (C,D) Embryos were injected at the 32-cell stage into blastomeres fated to become epidermis (A4) with the inducible construct Smad7GR to target injections to epidermis. Activation of the construct by the addition of dexamethasone during the gastrula stage results in ectopic expression of Snail2 (arrow in C; 25%, n=40). However, when activated during the maintenance phase, no ectopic expression is observed (D; 0%, n=20). No effect is seen in the absence of dexamethasone (not shown; 0%, n=31). (F,G) Small groups of ectodermal cell expressing BMP4 were grafted (arrows) next to the NC. When grafted during gastrulation, a strong inhibition of the NC was observed (F; 100%, n=25). However, when BMP4 cell were grafted during the maintenance phase, no inhibition was observed (G; 0%, n=55). Grafts of cell injected with FDX alone had no effect (not shown; 0%, n=42). The graft was recognised by immunostaining against fluorescein, as FDX was used as a lineage tracer (blue). (E) Summary of Smad7GR injections. (H) Summary of graft of BMP4-expressing cells. (I-K) Positive control to ensure sufficient BMP4 is being released to inhibit NC induction. (I) A small cluster of animal cap cells taken from an embryo injected with FDX or BMP4 mRNA (blue) was conjugated with an explant of stage 10.5 animal cap (AC) and DLMZ, in which NC markers are normally induced. (J) Explants of AC/DLMZ conjugated with cells expressing FDX show strong expression of Snail2 (85%, n=26). (K) Explants of AC/DLMZ conjugated with cells expressing BMP4/FDX show a dramatic inhibition in Snail2 expression (10% expressing Snail2, n=35). (L) Percentage of Sox2 or Snail2 expression after injecting different amounts of Smad7GR into A4 blastomere of a 32-cell stage embryo, as described in C,D. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

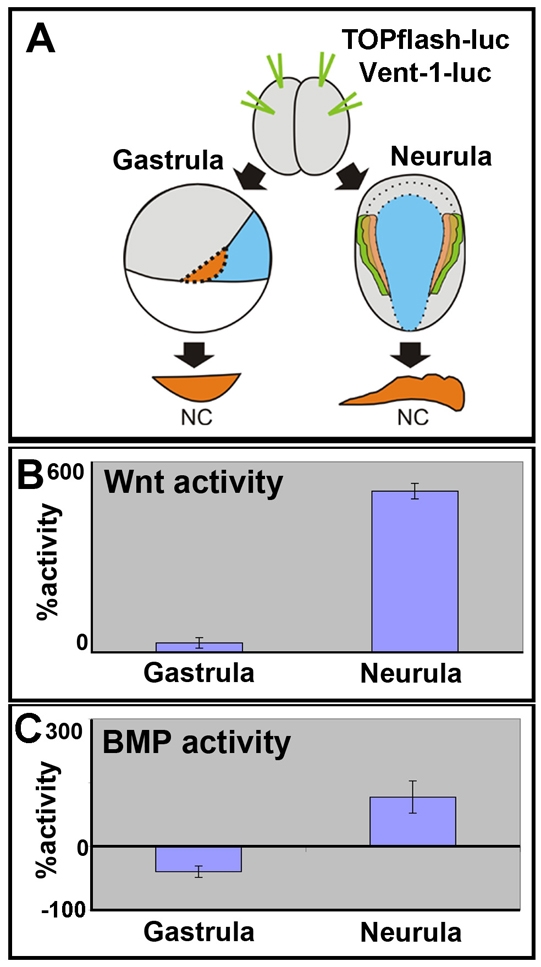

To examine dynamic changes in levels of signaling, we measured levels of Wnt or BMP activity in the NC using the TOPflash luciferase reporter or BMP reporter construct (Fig. 7A). Embryos were injected in the animal hemisphere with the reporter constructs and the luciferase activity we measured at the gastrula (from stage 10 until 12) or neurula (stage 16-18) stages. As our previous results predicted, the level of Wnt activity is kept low in the prospective NC during the early part of gastrulation (stage 10, not shown), with a rise in activity seen at mid gastrula that corresponds to NC induction step (Fig. 7B, gastrula bar). Furthermore, we see a continual rise in Wnt activity during neurulation, consistent with its role in NC maintenance (Fig. 7B, neurula bar). For BMP signaling, we made use of a Vent1-luciferase reporter. As predicted, levels of BMP signaling are lower in the NC than in the epidermis during gastrulation (Fig. 7C, gastrula bar). Interestingly, we observe a sharp rise in the relative levels of BMP signaling during neurulation (Fig. 7C, neurula bar). This correlates both with the requirement of high levels of BMP for maintenance and the observation that BMP4 is expressed at high levels in the neural folds from stage 16 onwards (Fig. 5N,Q).

Fig. 7.

Changes in Wnt and BMP activity during NC development. (A) Two-cell stage embryo received animal and equatorial injections of the indicated reporter constructs. The NC was dissected at the gastrula or neurula stages and luciferase was measured. (B) Measurements of canonical Wnt activity using the TOPflash luciferase reporter in NC explants. Activity expressed as the percentage of activity seen in stage 10 NC explants. (C) Measurements of BMP activity using the Vent1 luciferase reporter in NC explants. Activity was determined as percentage of activity in epidermal explants of the same stage and shown normalised to activity in the epidermis.

DISCUSSION

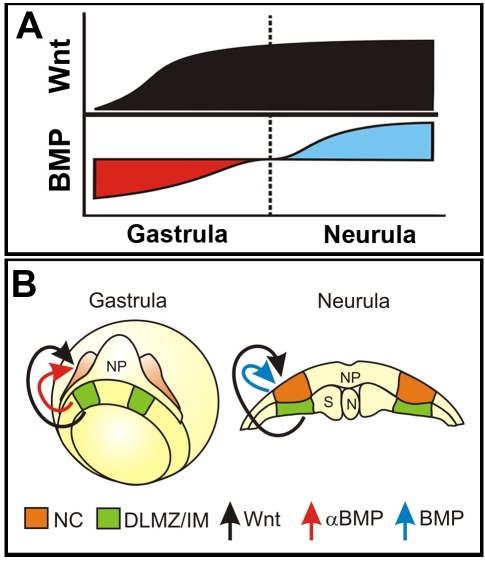

We propose a novel, two-step model for NC induction and identify the signals required for each step (Fig. 8A,B). First, the induction step at gastrula stage when Wnt activation and BMP inhibition are required. The level of both pathways is regulated by signals secreted by the DLMZ which is adjacent to the prospective NC. Second, the maintenance step at neurula stages, when activation of both Wnt and BMP is required and provided by signals secreted from the IM and adjacent ectoderm. This model emphasises the importance of the timing at which ectoderm is exposed to different signals during an inductive event.

Fig. 8.

Model of NC specification in two steps. (A) A diagram summarising the different temporal requirements and activities for Wnt and BMP pathways during NC development. (B) Model of NC induction at the gastrula and maintenance at the neurula stages.

The different requirements for BMP signals at the gastrula or neurula steps resolves a controversy about apparently discrepant results between experiments performed in chick and frog. In chick embryos, only high levels of BMP signalling were reported to be important for NC induction (Liem et al., 1995; Endo et al., 2002), whereas in Xenopus and zebrafish embryos an inhibition of BMP has been reported as a condition for NC induction (LaBonne and Bronner-Fraser, 1998; Marchant et al., 1998; Nguyen et al., 1998; Glavic et al., 2004; Villaneuva et al., 2002). However, the chick experiments were performed at neurula stages, much later than the gastrula stages used for the Xenopus and zebrafish experiments. Moreover in chick and Xenopus embryos the levels of phosphorylated Smad1, a read-out of BMP activity, rises in the neural fold only at neurula stages, being lower in the prospective NC region earlier in development (Faure et al., 2002; Schohl and Fagotto, 2002). We propose that the chick experiments were performed at the maintenance phase of NC induction and thus are consistent with our findings in the frog, that show a necessity of high BMP level at this step. Interestingly, a recent paper demonstrated that NC induction also initiates during gastrulation in chicks (Basch et al., 2006) and it is possible that this early phase requires an inhibition of BMP signalling. Thus, our detailed findings in Xenopus are likely to reflect pathways and phases that are common to all vertebrates.

Mesoderm as NC inducer

The DLMZ has, for a long time, been known to have NC-inducing properties (Raven and Kloos, 1945; Mayor et al., 1995; Bonstein et al., 1998; Marchant et al., 1998; Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003) (this work). We show here that the DLMZ, which becomes intermediate mesoderm (IM), moves during gastrulation to underlie the NC cells. This mesoderm has the ability to induce NC markers directly, without neural induction, and is essential for NC maintenance.

The expression of Wnt and BMP signal components fit with our model. During gastrulation, Wnt8 is expressed in the lateral and ventral mesoderm, while chordin is expressed in dorsal mesoderm. It is interesting to note that the only tissue co-expressing Wnt8 and chordin is the DLMZ, which is the only mesodermal tissue able to induce NC. At the neurula stage the IM continues to produce the NC inductive signal Wnt, but no longer expresses chordin (or any other BMP antagonist) (Sasai et al., 1994; Smith and Harland, 1992; Hemmati-Brivanlou et al., 1994). The absence of BMP antagonist in the IM and the rise in BMP4 expression in the neural fold lead to the increase in BMP activity necessary for the NC maintenance step.

Wnt signalling in NC induction by mesoderm

There is compelling evidence indicating that Wnt signalling participates in NC induction in several species (reviewed by Wu et al., 2003; Yanfeng et al., 2003). However, the role of Wnt signals from the DLMZ has been challenged (Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003). No inhibition of NC by the intracellular Wnt inhibitors such as GSK3 or dominant-negative TCF3 was found (Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003). However, as the activity of these antagonists was tested only on cement gland expansion, it remains possible that these two intracellular components of the Wnt pathway did not fully block Wnt function. Indeed, we show here that similar conditions to those published (Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003) expand cement gland, without affecting NC. Higher levels of Wnt inhibition are required to impair NC formation. This observation solves a long-standing controversy about the role of Wnt signals on NC induction by mesoderm (see Huang and Saint-Jeannet, 2004) and it is consistent with a recent publication that places Wnt8 as downstream target of FGF8 and rules out FGF8 as a NC inductive signal produced by the mesoderm (Hong et al., 2008).

As Wnt1, Wnt2b and Wnt3a are produced in the dorsal neural tube in mouse, chick, frog and zebrafish (Hollyday et al., 1995; Molven et al., 1991; Roelink and Nusse, 1991; Wolda et al., 1993; Landesman and Sokol, 1997), and not in the DLMZ, they cannot be involved in the DLMZ-inducing activities, but they could be involved in the later maintenance step. Wnt7b is present from the blastula stage, but its pattern of gene expression is too ubiquitous to be a specific inducer of NC cells (Chang and Hemmati-Brivanlou, 1998). Wnt6 is expressed in the non-neural ectoderm of chick embryos at the time of NC maintenance and is therefore a good candidate to mediate this late step of induction (Garcia-Castro et al., 2002; Schubert et al., 2002). This leaves Wnt8 as the only Wnt candidate described to date that it is expressed in the DLMZ and the IM (this work) (Christian and Moon, 1993). In zebrafish, Wnt8 morpholinos prevent the expression of early NC markers (Lewis et al., 2004) and overexpression of Wnt8 in Xenopus embryos leads to an expansion of NC cells (LaBonne and Bronner-Fraser, 1998). Furthermore, expression of Wnt8 in neuralised animal caps is able to induce strong expression of NC markers (LaBonne and Bronner-Fraser, 1998). A recent paper also proposes the notion that Wnt8 is the NC inducer in Xenopus embryos (Hong et al., 2008), which is consistent with the results reported here.

The observation that activating β-catenin within NC explants is alone sufficient for the maintenance of the NC at first appears to contradict the requirement for BMP in this process. It is widely accepted that the loss-of-function experiments are more informative that the gain-of function experiments as adding an excess of a molecule, in our case an inductive signal, could activate other pathways that are not normally involved in the natural event. The activation of β-catenin in this experiment is likely to be at much higher levels than that received by the NC during development. Activation of Wnt at this level might thus be sufficient for maintenance, whereas both pathways are required during normal development. The same could be argued for the apparent sufficiency of BMP4 in this process. These observations emphasise the importance of analysing both sufficiency and requirement for signalling pathways in an inductive event. In addition, it is well known that the activation of Wnt signalling in animal caps, along with an inhibition of BMP signalling or in the presence of neural tissue, is capable of inducing a robust expression of NC markers (Saint-Jeannet et al., 1997; LaBonne and Bronner-Fraser, 1998; Lekven et al., 2001; Deardorff et al., 2001; Garcia-Castro et al., 2002; Tribulo et al., 2003; Lewis et al., 2004; Bastidas et al., 2004; Carmona-Fontaine et al., 2007). Presumably in this context, after the initial induction of NC, the level of Wnt signalling is high enough to compensate for the lower level of BMP signalling in the subsequent maintenance of induction. Alternatively, activated Wnt signalling could interact with the endogenous BMP4 present in the neural fold or in the animal cap, leading to NC maintenance.

In addition to the requirement of BMP and Wnt, it has recently been shown that endothelin 1 plays an important role in the maintenance of the NC (Bonano et al., 2008). It is possible that all three pathways are acting in parallel to maintain the NC, alternatively BMP and Wnt signals might act to maintain the NC by upregulating the endothelin receptor Ednra, although this requires further attention.

This work highlights the importance of looking the spatial relationship of tissues during time. It is likely that all tissues are releasing different signals during development but not all of them are close enough to produce an effective signal. In processes as dynamic as gastrulation and neurulation, this should not be neglected. By taking into account these parameters, we have been able to solve two controversies in NC induction.

We thank Carlos Carmona-Fontaine and Helen Matthews for comment in the manuscript; J. Green, M. Whitman, L. Dale, C. Niehrs and C. Hill for provided us reagents; and C. Carmona-Fontaine for Fig. 5P. This investigation was supported by grants to R.M. from the MRC and BBSRC. B.S. is a BBSRC PhD scholarship holder. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

References

- Aybar, M. J., Nieto, M. A. and Mayor, R. (2003). Snail precedes slug in the genetic cascade required for the specification and migration of the Xenopus neural crest. Development 130, 483-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch, M. L., Garcia-Castro, M. I. and Bronner-Fraser, M. (2004). Molecular mechanisms of neural crest induction. Birth Defects Res. Part C Embryo Today 72, 109-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch, M. L., Bronner-Fraser, M. and Garcia-Castro, M. (2006). Specification of the NC occurs during gastrulation and requires Pax7. Nature 441, 218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastidas, F., De Calisto, J. and Mayor, R. (2004). Identification of neural crest competence territory: role of Wnt signaling. Dev. Dyn. 229, 109-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonano, M., Tríbulo, C., De Calisto, J., Marchant, L., Sánchez, S. S., Mayor, R. and Aybar, M. J. (2008). A new role for the Endothelin-1/Endothelin-A receptor signaling during early neural crest specification. Dev. Biol. 323, 114-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonstein, L., Elias, S. and Frank, D. (1998). Paraxial-fated mesoderm is required for neural crest induction in Xenopus embryos. Dev. Biol. 193, 156-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona-Fontaine, C., Acuna, G., Ellwanger, K., Niehrs, C. and Mayor, R. (2007). Neural crests are actively precluded from the anterior neural fold by a novel inhibitory mechanism dependent on Dickkopf1 secreted by the prechordal mesoderm. Dev. Biol. 309, 208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C. and Hemmati-Brivanlou, A. (1998). Neural crest induction by Xwnt7B in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 194, 129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian, J. L. and Moon, R. T. (1993). Interactions between Xwnt-8 and Spemann organizer signaling pathways generate dorsoventral pattern in the embryonic mesoderm of Xenopus. Genes Dev. 7, 13-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, M. A., Tan, C., Conrad, L. J. and Klein, P. S. (1998). Frizzled-8 is expressed in the Spemann organizer and plays a role in early morphogenesis. Development 125, 2687-2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardoff, M. A., Tan, C., Saint-Jeannet, J. P. and Klein, P. S. (2001). A role for frizzled 3 in the neural crest development. Development 128, 3655-3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingos, P. M., Itasaki, N., Jones, C. M., Mercurio, S., Sargent, M. G., Smith, J. C. and Krumlauf, R. (2001). The Wnt/β-catenin pathway posteriorizes neural tissue in Xenopus by an indirect mechanism requiring FGF signalling. Dev. Biol. 239, 148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo, Y., Osumi, N. and Wakamatsu, Y. (2002). Bimodal functions of Notch-mediated signaling are involved in neural crest formation during avian ectoderm development. Development 129, 863-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure, S., de Santa Barbara, P., Roberts, D. J. and Whitman, M. (2002). Endogenous patterns of BMP signaling during early chick development. Dev. Biol. 244, 44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Castro, M. I., Marcelle, C. and Bronner-Fraser, M. (2002). Ectodermal Wnt functions a neural crest inducer. Science 297, 848-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavic, A., Silva, F., Aybar, M. J., Bastidas, F. and Mayor, R. (2004). Interplay between Notch signaling and the homeoprotein Xiro1 is required for neural crest induction in Xenopus embryos. Development 131, 347-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, F. S., Wheeler, G. N. and Hoppler, S. (2001). Difference in XTcf-3 dependency accounts for change in response to beta-catenin-mediated Wnt signalling in Xenopus blastula. Development 128, 2063-2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland, R. M. (1991). In situ hybridization: An improved whole-mount method for Xenopus embryos. Methods Cell Biol. 36, 685-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland, R. and Weintraub, H. (1985). Translation of mRNA injected into Xenopus oocytes is specifically inhibited by antisense RNA. J. Cell Biol. 101, 1094-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeg-Truesdell, E. and LaBonne, C. (2006). Neural induction in Xenopus requires inhibition of Wnt-β-catenin signaling. Dev. Biol. 298, 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati-Brivanlou, A., Kelly, O. G. and Melton, D. A. (1994). Follistatin, an antagonist of activin, is expressed in the Spemann organizer and displays direct neuralizing activity. Cell 77, 283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollyday, M., McMahon, J. A. and McMahon, A. P. (1995). Wnt expression patterns in chick embryo nervous system. Mech. Dev. 52, 9-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, C. S., Park, B. Y. and Saint-Jeannet, J. P. (2008). Fgf8a induces neural crest indirectly through the activation of Wnt8 in the paraxial mesoderm. Development 135, 3903-3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppler, S., Brown, J. D. and Moon, R. T. (1996). Expression of a dominant-negative Wnt blocks induction of MyoD in Xenopus embryos. Genes Dev. 10, 2805-2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X. and Saint-Jeannet, J.-P. (2004). Induction of the neural crest and the opportunities of life on the edge. Dev. Biol. 275, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecker, C. and Niehrs, C. (2001). A morphogen gradient of Wnt/{beta}-catenin signalling regulates anteroposterior neural patterning in Xenopus. Development 128, 4189-4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintner, C. R. and Brockes, J. P. (1984). Monoclonal antibodies identify blastemal cells derived from dedifferentiating muscle in newt limb regeneration. Nature 308, 67-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi, M., Mizuseki, K., Sasai, N., Yamazaki, H., Shiota, K., Nakanishi, S. and Sasai, Y. (2000). Requirement of Sox2-mediated signaling for differentiation of early Xenopus neuroectoderm. Development 127, 791-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBonne, C. and Bronner-Fraser, M. (1998). Neural crest induction in Xenopus: evidence for a two signal model. Development 125, 2403-2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landesman, Y. and Sokol, S. Y. (1997). Xwnt-2b is a novel axis-inducing Xenopus Wnt, which is expressed in embryonic brain. Mech. Dev. 63, 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDouarin, N. M. and Kalcheim, C. (1999). The Neural Crest, 2nd edn. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Lekven, A. C., Thorpe, C. J., Waxman, J. S. and Moon, R. T. (2001). Zebrafish Wnt8 encodes two Wnt8 proteins on a bicistronic transcript and is required for mesoderm and neuroectoderm patterning. Dev. Cell 1, 103-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J. L., Bonner, J., Modrell, M., Ragland, J. W., Moon, R. T., Dorsky, R. I. and Raible, D. W. (2004). Reiterated Wnt signaling during zebrafish neural crest development. Development 131, 12299-12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem, K. F., Jr, Tremml, G., Roelink, H. and Jessell, T. M. (1995). Dorsal differentiation of neural plate cells by BMP-mediated signals from epidermal ectoderm. Cell 82, 969-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linker, C., Bronner-Fraser, M. and Mayor, R. (2000). Relationship between gene expression domains of Xsnail, Xslug, and Xtwist and cell movement in the prospective neural crest of Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 224, 215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancilla, A. and Mayor, R. (1996). Neural crest formation in Xenopus laevis: mechanism of Xslug induction. Dev. Biol. 177, 580-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant, L., Linker, C., Ruiz, P., Guerrero, N. and Mayor, R. (1998). The inductive properties of mesoderm suggest that the neural crest are specified by a BMP gradient. Dev. Biol. 198, 319-329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, R., Morgan, R. and Sargent, M. G. (1995). Induction of the prospective neural crest of Xenopus. Development 121, 767-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, R., Guerrero, N. and Martinez, C. (1997). Role of FGF and noggin in the neural crest induction. Dev. Biol. 189, 1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar, M., van de Wetering, M., Oosterwegel, M., Peterson-Maduro, J., Godsave, S., Korinek, V., Roose, J., Destree, O. and Clevers, H. (1996). XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates beta-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell 86, 391-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molven, A., Njolstad, P. R. and Fjose, A. (1991). Genomic structure and restricted neural expression of the zebrafish wnt-1 (int-1) gene. EMBO J. 10, 799-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsoro-Burq, A. H., Fletcher, R. B. and Harland, R. M. (2003). Neural crest induction by paraxial mesoderm requires FGF signals. Development 130, 3111-3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moury, J. D. and Jacobson, A. G. (1990). The origins of neural crest cells in the axolotl. Dev. Biol. 141, 243-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V. H., Schimd, B., Trout, J., Connors, S. A., Ekker, M. and Mullins, M. (1998). Ventral and lateral regions of the zebrafish gastrula, including the neural crest progenitors, are established by a bmp2/swirl pathway genes. Dev. Biol. 199, 93-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop, P. D. and Faber, J. (1967). Normal Table of Xenopus laevis, Daudin, 2nd edn. Amsterdam: North Holland.

- Oelgeschlager, M., Kuroda, H., Reversade, B. and De Robertis, E. M. (2003). Chordin is required for the Spemann organizer transplantation phenomenon in Xenopus embryos. Dev. Cell 4, 219-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven, C. P. and Kloos, J. (1945). Induction by medial and lateral pieces of archenteron roof, with special reference to the determination of the neural crest. Acta Neerl. Norm. Pathol. 55, 348-362. [Google Scholar]

- Roelink, H. and Nusse, R. (1991). Expression of two members of the Wnt family during mouse development-restricted temporal and spatial patterns in the developing neural tube. Genes Dev. 5, 5381-5388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Jeannet, J. P., He, X., Varmus, H. E. and Dawid, I. B. (1997). Regulation of dorsal fate in the neuraxis by Wnt-1 and Wnt-3a. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 13713-13718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasai, N., Mizuseki, K. and Sasai, Y. (2001). Requirement of FoxD3-class signaling for neural crest determination in Xenopus. Development 128, 2525-2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasai, Y., Lu, B., Steinbeisser, H., Geissert, D., Gont, L. K. and De Robertis, E. M. (1994). Xenopus chordin: A novel dorsalizing factor activated by organizer-specific homeobox genes. Cell 79, 779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schohl, A. and Fagotto, F. (2002). β-catenin, MAPK and Smad signaling during early Xenopus development. Development 129, 37-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, F. R., Mootoosamy, R. C., Walters, E. H., Graham, A., Tumiotto, L., Munsterberg, A. E., Lumsden, A. and Dietrich, S. (2002). Wnt6 marks sites of epithelial transformations in the chick embryo. Mech. Dev. 114, 143-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selleck, M. A. and Bronner-Fraser, M. (1995). Origins of neural crest: the role of neural plate-epidermal interactions. Development 121, 525-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W. C. and Harland, R. M. (1992). Expression cloning of noggin, a new dorsalizing factor localized to the Spemann organizer in Xenopus embryos. Cell 70, 829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol, S. Y. (1996). Analysis of Dishevelled signalling pathways during Xenopus development. Curr. Biol. 6, 1456-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steventon, B., Carmona-Fontaine, C. and Mayor, R. (2005). Genetic network during neural crest induction: from cell specification to cell survival. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribulo, C., Aybar, M. J., Nguyen, V. H., Mullins, M. C. and Mayor, R. (2003). Regulation of Msx genes by a Bmp gradient is essential for neural crest specification. Development 130, 6441-6452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva, S., Glavic, A., Ruiz, P. and Mayor, R. (2002). Posteriorization by FGF, Wnt and retinoic acid is required for neural crest induction. Dev. Biol. 241, 289-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, F. C., Welch, J. V. and Dale, L. (1999). Bone morphogenetic protein 1 regulates dorsal-ventral patterning in early Xenopus embryos by degrading chordin, a BMP4 antagonist. Mech. Dev. 86, 75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawersik, S., Evola, C. and Whitman, M. (2005). Conditional BMP inhibition in Xenopus reveals stage-specific roles for BMPs in neural and neural crest induction. Dev. Biol. 277, 425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolda, S. L., Moody, C. J. and Moon, R. T. (1993). Overlapping expression of Xwnt-3A and Xwnt-1 in neural tissue of Xenopus laevis embryos. Dev. Biol. 155, 46-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., Saint-Jeannet, J. P. and Klein, P. S. (2003). Wnt-frizzled signaling in neural crest formation. Trends Neurosci. 26, 40-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanfeng, W., Saint-Jeannet, J. P. and Klein, P. S. (2003). Wnt-frizzled signaling in the induction and differentiation of the neural crest. BioEssays 25, 317-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]