Summary

Syndecan-4 (Syn4) is a heparan sulphate proteoglycan that is able to bind to some growth factors, including FGF, and can control cell migration. Here we describe a new role for Syn4 in neural induction in Xenopus. Syn4 is expressed in dorsal ectoderm and becomes restricted to the neural plate. Knockdown with antisense morpholino oligonucleotides reveals that Syn4 is required for the expression of neural markers in the neural plate and in neuralised animal caps. Injection of Syn4 mRNA induces the cell-autonomous expression of neural, but not mesodermal, markers. We show that two parallel pathways are involved in the neuralising activity of Syn4: FGF/ERK, which is sensitive to dominant-negative FGF receptor and to the inhibitors SU5402 and U0126, and a PKC pathway, which is dependent on the intracellular domain of Syn4. Neural induction by Syn4 through the PKC pathway requires inhibition of PKCδ and activation of PKCα. We show that PKCα inhibits Rac GTPase and that c-Jun is a target of Rac. These findings might account for previous reports implicating PKC in neural induction and allow us to propose a link between FGF and PKC signalling pathways during neural induction.

Keywords: Neural induction, Syndecan-4, FGF, PKC, Rac, JNK, AP-1, c-Fos

INTRODUCTION

The `default model' of neural induction proposes that neural development occurs as a result of the inhibition of BMP signalling in the embryonic ectoderm, and that in the absence of cell-cell signalling, ectodermal cells will adopt a neural fate (Munoz-Sanjuan and Brivanlou, 2002; Weinstein and Hemmati-Brivanlou, 1997). There is compelling evidence that BMP signalling and its modulation by endogenous inhibitors are involved in the specification of neural and non-neural domains in Xenopus (Iemura et al., 1998; Piccolo et al., 1996; Sasai et al., 1994; Smith et al., 1993). However, several challenges to the default model have originated from studies in chick and ascidians, as well as from more recent experiments in Xenopus (for a review, see Stern, 2005). There is now convincing evidence that in addition to BMP inhibition, other signals are required for neural induction. One of these is FGF, which is involved in the induction of neural tissue in chick and Xenopus, as well as in Ciona (Hongo et al., 1999; Launay et al., 1996; Streit et al., 2000; Tannahill et al., 1992; Wilson et al., 2000; Bertrand et al., 2003). It has been proposed that FGF regulates neural induction in animal caps and in Xenopus embryos by activation of MAPK, which in turn phosphorylates the BMP target Smad1, contributing to the inhibition of BMP signalling (Fuentealba et al., 2007; Graves et al., 1994; Grunz and Tacke, 1989; Hartley et al., 1994; Kuroda et al., 2005; Pera et al., 2003; Sato and Sargent, 1989). However, it is not known how the activity of FGF is regulated in the embryo to account for its role during neural induction. As it is well established that several proteoglycans (PGs) can regulate the activity of FGF, in some cases working as co-receptors, we decided to study the role of PGs as potential modulators of FGF during neural induction.

PGs are extracellular glycoproteins that contain sulphated glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains. Biochemical and cell culture assays have implicated PGs as co-regulators of many growth factors, including FGF, HGF, Wnt, TGFβ and BMP (Bernfield et al., 1999; Iozzo, 1998). The GAG chains can be of heparan, chondroitin or dermatan sulphate (Bernfield et al., 1999; Iozzo, 1998). Syndecan-4 (Syn4) is a heparan sulphate PG reported to modulate FGF signalling in vitro (Iwabuchi and Goetinck, 2006; Tkachenko et al., 2004; Tkachenko and Simons, 2002). In addition, Syn4 interacts with chemokines (Brule et al., 2006; Charnaux et al., 2005) and with the planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway (Matthews et al., 2008; Muñoz et al., 2006). As Syn4 also interacts with fibronectin and integrins and is required for the formation of focal adhesions (Woods and Couchman, 2001), its main role has been thought to be in cell migration. However, Syn4 is also able to modulate PKC- and small GTPase-dependent intracellular signalling (Bass et al., 2007; Horowitz et al., 1999; Horowitz and Simons, 1998; Keum et al., 2004; Matthews et al., 2008).

Here, we investigate the role of Syn4 in neural induction in Xenopus. We report that Syn4 is expressed in ectoderm and becomes restricted to the neural plate. Loss-of-function experiments show that Syn4 is required for neural induction, whereas misexpression of Syn4 can induce the expression of neural markers in animal caps or ventral ectoderm. We also report that Syn4 activates two parallel pathways: the FGF/ERK pathway, previously implicated in neural induction, and the PKCα/Rac/JNK pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Xenopus embryos, animal cap assay and microinjection

Xenopus embryos were obtained as described (Newport and Kirschner, 1982). Embryos were staged according to Niewkoop and Faber (Niewkoop and Faber, 1967). For normal development, embryos were incubated in 0.1× Marc's Modified Ringer's Solution (MMR) until they reached the appropriate stage. Animal caps were dissected at stage 9 and analysed at stage 14. Injected mRNA was synthesised using the mMessage mMachine Kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer's instructions. For the RacN17 experiments, we added a poly(A) sequence that was not included in the original clone (Tahinci and Symes, 2003). Grafting of neuroectoderm has been described (Linker and Stern, 2004). For 32-cell stage injection, the cell lineage was as described (Moody, 1987).

Morpholino oligonucleotide and whole-mount in situ hybridisation

The Syn4 morpholino oligo (MO) was the same as that described previously (Muñoz et al., 2006; Matthews et al., 2008). For rescue experiments, we used point-mutated Syn4 as described (Matthews et al., 2008).

For in situ hybridisation, we followed the procedures described by Harland (Harland, 1991), with the modifications described by Kuriyama et al. (Kuriyama et al., 2006).

Western blot

SDS-PAGE and blotting were performed using NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris Gels (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions, and PVDF membrane (Amersham) was used for transfer blotting. Samples were taken from animal caps at the appropriate stages, and homogenised with buffer containing anti-phosphorylation reagent (Sigma) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Antibodies for p42/44 MAPK and phosphorylated p42/44 MAPK were used at 1/1000 (Cell Signaling) in 4% BSA in TBST, and anti c-Fos antibody (Santa Cruz) was used at 1/400 in 10% horse serum in TBST. After three washes, anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was applied as secondary antibody at 1/25,000. Signal was visualised with luminescent HRP substrate and exposed to film (Fuji).

Confocal microscopy

The mRNA for fluorescent fusion proteins (PKCδ-EGFP or PKCα-EGFP) was injected at the 2-cell stage in both blastomeres. The membrane was visualised by co-injection of mRNA for membrane monomeric Cherry (mCherry) protein. In Fig. 5, the animal caps were dissected at stage 8, treated with 2 μM phorbol ester (Sivak et al., 2005) or 10 ng/ml FGF2 (R&D), and fixed in MEMFA for 20 minutes. In Fig. 6, mCherry mRNA with MO was injected into 16-cell stage embryos after injection of PKCα-EGFP mRNA at the 2-cell stage. Images were taken with a Leica SP2 confocal microscope.

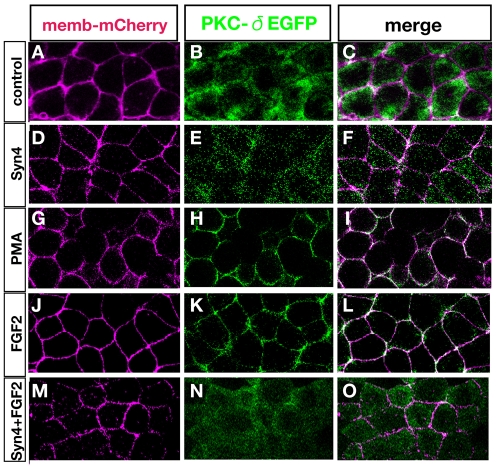

Fig. 5.

Membrane translocation of PKCδ by FGF is inhibited by Syn4. Xenopus animal caps analysed by confocal microscopy after injection/treatment as indicated. (A-C) Control animal cap shows cytoplasmic localisation of PKCδ. (D-F) Animal caps injected with Syn4 mRNA. PKCδ shows cytoplasmic distribution. (G-L) Phorbol ester (PMA; G-I) or FGF2 (J-L) triggers the translocation of PKCδ into the membrane. (M-O) Syn4 inhibits the translocation of PKCδ activated by FGF2.

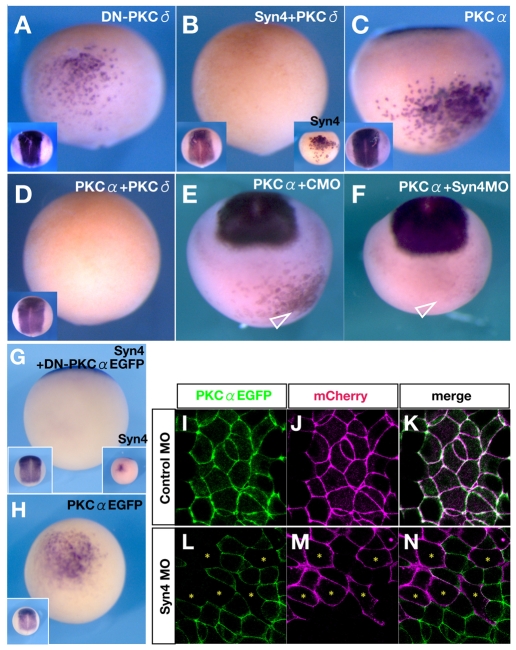

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of PKCδ or activation of PKCα is essential for neural induction by Syn4. (A-H) Sox2 expression in Xenopus embryos injected, as indicated, into A4 blastomeres at the 32-cell stage. (A-D) Ventral view, dorsal to the top. Insets on left show a dorsal view. (A) Dominant-negative Xenopus PKCδ (DN-PKCδ). Note the ectopic Sox2 induction (48%, n=71). (B) Co-injection of Syn4 and Xenopus full-length PKCδ mRNAs represses the ectopic expression of Sox2 (18%, n=91). Inset on the right shows the ventral ectopic Sox2 expression induced by Syn4 mRNA (95%, n=85). (C) Human (h) PKCα mRNA can induce ectopic Sox2 expression (68%, n=92). (D) Co-injection of hPKCα and PKCδ mRNAs shows inhibition of neural induction (20%, n=124). (E) Co-injection of hPKCα with control MO (CMO). Arrowhead indicates the ectopic expression of Sox2 (70%, n=68). (F) Co-injection of hPKCα mRNA with Syn4 MO. Sox2 induction is not observed in the injected cells (arrowhead) (23%, n=51). (G) Co-injection of Syn4 and a dominant-negative form of PKCα (DN-PKCα-EGFP) inhibits Sox2 expression (15%, n=51). (H) Injection of PKCα-EGFP mRNA. Ectopic induction of Sox2 is similar to that upon PKCα injection, showing that EGFP does not affect the activity of the fusion protein. (I-N) Confocal images of animal caps injected as indicated. PKCα-EGFP mRNA was injected into both blastomeres at the 2-cell stage. At the 16-cell stage, Syn4 or control MO and membrane Cherry mRNA were injected into one blastomere. (I-K) PKCα-EGFP spontaneously localises at the membrane, colocalising with membrane Cherry. (L-N) The distribution of Syn4 MO can be identified by the fluorescence of mCherry. Note that cells with a high level of Syn4 MO (asterisks) exhibit a low level of PKCα-EGFP in the membrane.

Clones and constructs

Full-length cDNA clones (NIBB) were used for the analysis of Syn4 expression; these give a stronger signal than the probe previously published by Muñoz et al. (Muñoz et al., 2006). The National Institute for Basic Biology (Japan) reference number of Syn4.1 is XL201e11, and Syn4.2 is XL457P08ex. The cDNA of the c-Fos gene was isolated from Xenopus neurula cDNA, and initially cDNA containing the 3′UTR was amplified by RT-PCR with the following primers (sequences according to EST clone MGC80305): XbaI-Xl-c-Fos Fw, 5′-CCGTCTAGAACAGAGCAGGATTTGCATTTATA-3′ and Xl-c-Fos Rv, 5′-ACAGAATTCACAACAAGTCCATGCCAGT-3′. Xenopus laevis c-Fos shares 63-65% identity with c-Fos from other species (data not shown). The Xenopus laevis c-Fos ORF was amplified using the following primers: ClaI-c-Fos Fw, 5′-ATATCGATGTATCACGCCTTCTCCAGCA-3′ and XhoI-c-Fos Rv, 5′-GCACTCGAGTGCCAATAGGGTAGGGGAGTT-3′. After checking that there were no mutations in the sequence, the ORF was subcloned into the pCS2+-GR vector.

Rac activation assay

Rac activity was analysed using the Rac1 Activation Assay Biochem Kit (Cytoskeleton). Animal caps were dissected at stage 9 and cultured until stage 10.5 (data not shown) or 11.5. The total amount of protein used to bind the PAK-RBD beads was adjusted in a pilot experiment using Bradford analysis (BioRad). Around 100 animal caps were dissected for each condition, cell lysates were centrifuged to remove the yolk fraction, and the supernatants were used for the GDP/GTP-binding reaction according to the manufacturer's instructions. Positive (GTP-bound) and negative (GDP-bound) controls were performed as described by the manufacturer. For pulldown of active Rac, 10 μg of PAK-RBD beads was applied to each sample, boiled with Laemmli sample buffer (Invitrogen) and loaded onto the gel.

RESULTS

Syn4 is required for neural induction

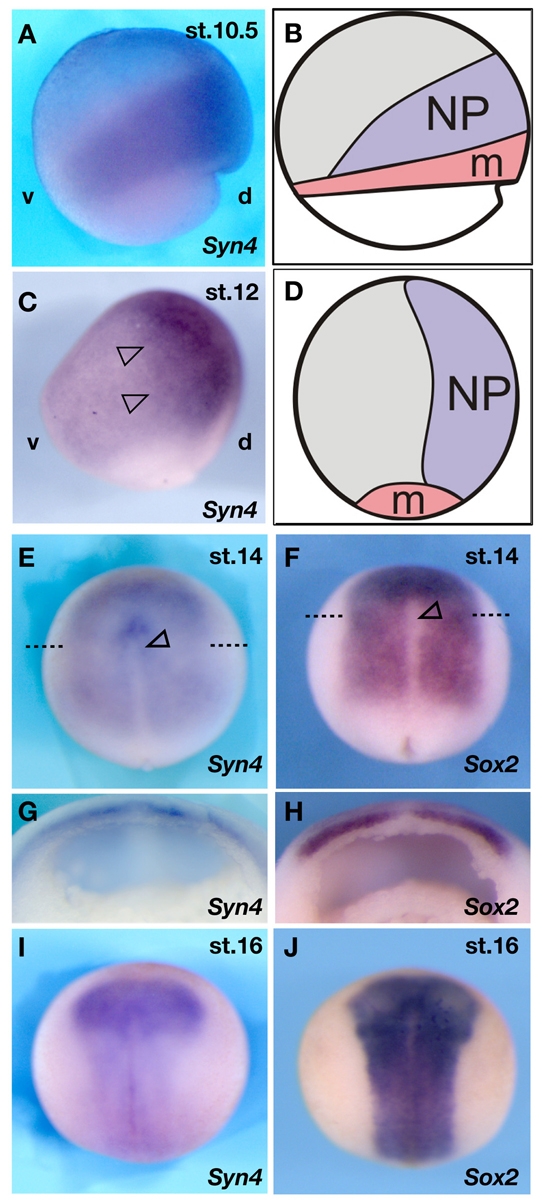

We started by examining the expression of Syn4 by whole-mount in situ hybridisation. As the mesodermal expression of Syn4 has already been described (Muñoz et al., 2006), we focused on the ectodermal expression pattern. A longer Syn4 probe (see Materials and methods), which gives stronger staining than the probe described by Muñoz et al. (Muñoz et al., 2006), allowed us to characterise the neuroectodermal expression of Syn4. During blastula stages, Syn4 is expressed transiently in a wide region of the ectoderm (Munoz et al., 2006) and very quickly becomes enriched in the prospective neural tissues at the early and mid-gastrula stages (Fig. 1A-D). During early neurula stages, Syn4 expression was detectable only in the neural plate (Fig. 1E,G,I), resembling the expression of the neural plate marker Sox2 (Fig. 1F,H,J).

Fig. 1.

Dynamic expression of Syn4 in the neural plate region. Whole-mount in situ hybridisation analysis of Syn4 and Sox expression. (A) Lateral view of a stage 10.5 Xenopus embryo showing Syn4 expression in the dorsal marginal zone. Dorsal (d) to the right; ventral (v), left; animal pole to the top. (B) Fate map of a stage 10.5 embryo, shown in the same orientation as in A. NP, prospective neural plate; m, prospective mesoderm. (C) At stage 12, Syn4 expression (arrowheads) is restricted to the dorsal region of the embryo (orientation as in A). (D) Fate map of a stage 12 embryo, shown in the same orientation as in C. NP, neural plate. (E) At stage 14, Syn4 expression is seen in the neural plate, but is absent from the dorsal midline (arrowhead). Dashed line indicates the plane of the section in G. (F) Stage 14 embryo showing Sox2 expression. The expression pattern is similar to that of Syn4 in E. Dashed line indicates the plane of the section in H. Arrowhead, dorsal midline. (G) Section of a stage 14 embryo, showing Syn4 expression. No expression is observed at the midline or in mesoderm. (H) Section of a stage 14 embryo, showing Sox2 expression (I) At stage 16, Syn4 expression is seen in the neural plate. (J) Sox2 expression at stage 16.

To determine whether Syn4 is required for neural induction, we performed loss-of-function experiments using a mixture of two antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (Syn4 MOs), as previously reported (Muñoz et al., 2006; Matthews et al., 2008). Injection of Syn4 MO into dorsal animal blastomeres at the 8-cell stage produced a strong inhibition of the neural plate markers Sox2 and Nrp1 on the injected side, whereas no inhibition was observed when a control MO was injected (Fig. 2A,B,E,F). A similar inhibition of neural plate markers was observed when the injected embryos were analysed at later stages, indicating that the effect of Syn4 MO is not merely a delay in gene expression, but a true inhibition (see Fig. S1A,B in the supplementary material). As the injection at the 8-cell stage might target some mesodermal cells and affect neural induction indirectly, we used two approaches to inhibit Syn4 selectively in the prospective neural plate. First, Syn4 MO was injected at the 32-cell stage into the A1 blastomere, which is fated to contribute to the neural plate but not to the mesoderm (Moody, 1987). Sox2 expression was inhibited in descendants of these Syn4 MO-injected cells (Fig. 2C). This is specific for Syn4 because it could be rescued by co-injection of mRNA encoding a mutated Syn4 that does not bind to the MO (Fig. 2D). As an alternative approach, prospective neural plate taken from an early neurula embryo injected with Syn4 MO or control MO was grafted into the early neurula of an uninjected host, creating an embryo in which Syn4 MO is present only in the neural plate. The control graft still showed normal Sox2 expression (Fig. 2G), whereas grafts of Syn4 MO-injected tissue showed loss of Sox2 expression (Fig. 2H, asterisk). These results show that Syn4 is required in the ectoderm for neural plate induction.

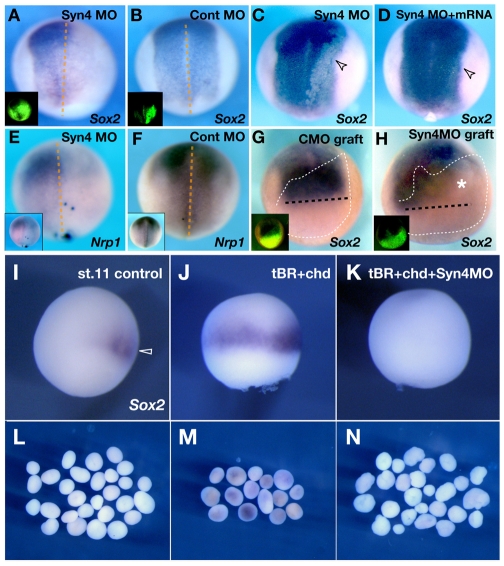

Fig. 2.

Syn4 is required for neural induction. Sox2 and Nrp1 expression was analysed by whole-mount in situ hybridisation. (A-H) MO-injected samples analysed at stage 14. The lineage tracer in shown in the insets. (A) Syn4 MO injected in one animal blastomere of an 8-cell stage Xenopus embryo. Note the inhibition of Sox2 expression on the injected (right-hand) side (60%, n=45). (B) Similar to A, but injection with control MO. No effect on Sox2 expression is observed (0%, n=57). (C) Syn4 MO was injected into the dorsal animal blastomere (A1) at the 32-cell stage. Note the inhibition of Sox2 expression in the injected region (arrowhead) (55%, n=50). (D) Syn4 mRNA mutated in the MO sequence region was co-injected with Syn4 MO into the A1 blastomere of a 32-cell stage embryo. Note the rescue of the expression of Sox2 (8%, n=66). (E) Syn4 MO injected into one animal blastomere of an 8-cell stage embryo. Note the inhibition of Nrp1 expression on the injected side (95%, n=42). (F) No inhibition is observed with the control MO (0%, n=21). (G) Control-morpholino-injected ectoderm was grafted into an uninjected embryo. Sox2 expression is normal (100%, n=10). Black dashed line indicates the anterior border of Sox2 expression. White dashed line outlines the graft. Inset shows the position of the graft by its fluorescence. (H) Syn4 MO-injected ectoderm was grafted into an uninjected embryo. Sox2 expression is absent from the grafted area (asterisk; 70%, n=10). Inset shows the position of the graft by its fluorescence. (I-N) Analysis of Sox2 expression at stage 11. (I) Expression of Sox2 is initially observed in the dorsal region (arrowhead). (J) Expansion of Sox2 expression by BMP inhibition [BMP antagonists: truncated BMP receptor (tBR) and chordin (chd) mRNA]. (K) Early induction of Sox2 was eliminated by co-injection of Syn4 MO (69%, n=50). (L) Control animal caps, showing no expression of Sox2. (M) Animal caps taken from embryos injected as in J, showing weak upregulation of Sox2. (N) Animal caps taken from embryos as in K. Co-injection of Syn4 MO blocks Sox2 induction.

To analyse the mechanism by which Syn4 MO blocks neural plate development, we asked whether it might interfere with BMP signalling. Inhibition of BMP signalling by a combination of BMP antagonists causes expansion of the early expression of Sox2 in the embryo and in animal caps analysed at stage 11 (Fig. 2I,J,L,M) (Rogers et al., 2008). When co-injected with these BMP antagonists, Syn4 MO still blocked Sox2 expression in the embryo and in animal caps (Fig. 2K,N), suggesting that Syn4 does not function as a BMP antagonist in neural induction. Furthermore, if Syn4 is a BMP antagonist, it would be expected to dorsalise mesoderm and to induce a secondary axis, as do all BMP antagonists (Harland, 1994). Whereas chordin mRNA did induce a secondary axis, no such effect was observed after injection of Syn4 mRNA (see Fig. S2A,B in the supplementary material), consistent with the notion that Syn4 does not block BMP signalling.

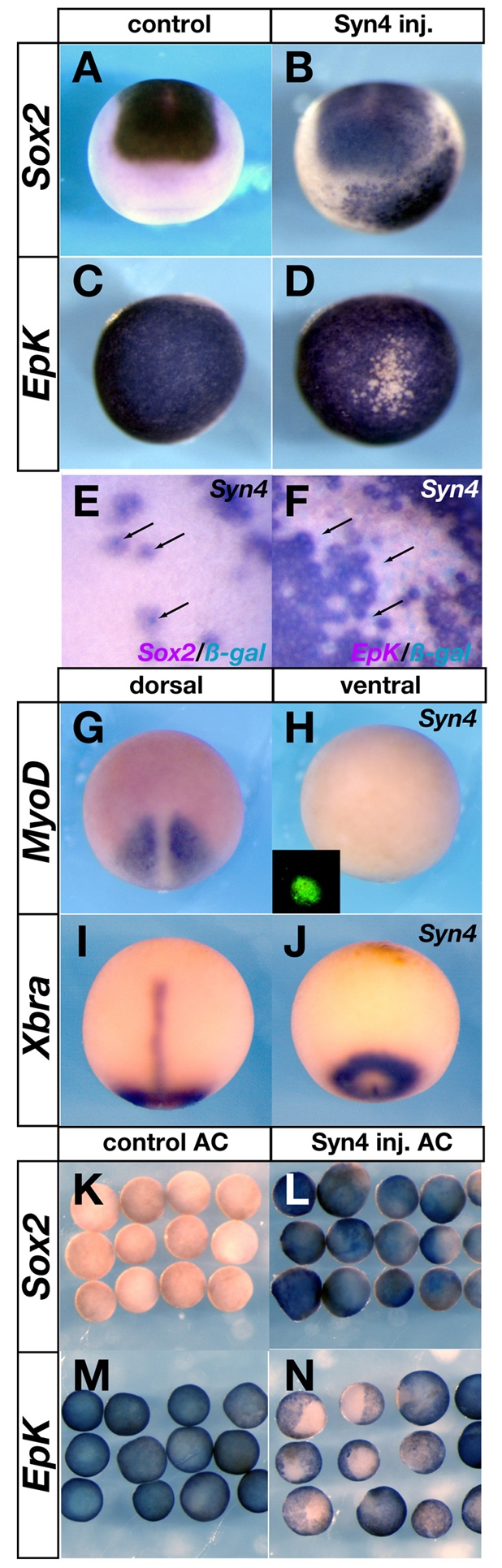

Overexpression of Syn4 neuralises the ectoderm

The above results suggest that Syn4 is required for neural plate formation. To test whether Syn4 can induce a neural fate, Syn4 mRNA was injected at the 32-cell stage into the A4 blastomere (which does not contribute cells to the neural plate) (Moody, 1987). Inhibition of BMP in this blastomere does not induce neural tissue (Linker and Stern, 2004). By contrast, injection of Syn4 mRNA into A4 did lead to induction of Sox2 and Sox3 in the ventral epidermis (Fig. 3A,B; see Fig. S2C,D in the supplementary material) and to inhibition of epidermal marker expression (Fig. 3C,D), without induction of mesodermal markers (Fig. 3G-J). The induction of neural markers by Syn4 is not transient, as they were still expressed at the late neurula stages (see Fig. S2H,I in the supplementary material). Interestingly, this neuralisation by Syn4 was not blocked by co-injection of a MO against chordin (see Fig. S2E-G in the supplementary material) (Oelgeschläger et al., 2003), which is consistent with the idea that neural induction by Syn4 is BMP independent. Furthermore, this induction of Sox2 is cell-autonomous to the descendants of the injected cell, as revealed by co-injection of nuclear β-galactosidase as a lineage tracer: all Sox2-positive, epidermal keratin (EpK)-negative cells exhibited X-Gal staining in the nucleus (Fig. 3E,F). Finally, overexpression of Syn4 induced neural plate markers and inhibited epidermal markers in isolated animal caps (Fig. 3K-N; see Fig. S2J,K in the supplementary material), without expression of mesodermal markers (not shown). Together, these gain- and loss-of-function experiments support a role for Syn4 in neural plate development.

Fig. 3.

Syn4 overexpression neuralises ectoderm. (A-D) Anterior view, dorsal to the top (A,B); ventral view (C,D). (A,C) 500 pg of NLS-β-gal mRNA was injected into the A4 blastomere of a 32-cell stage Xenopus embryo, and the expression of Sox2 (A) and epidermal keratin (Epk) (C) was analysed by in situ hybridisation. (B,D) 1 ng of Syn4 mRNA was injected into the A4 blastomere of a 32-cell stage embryo, and the expression of Sox2 (C; 96% of induction, n=87) and Epk (D; 80% of inhibition, n=70) was analysed. (E,F) Higher magnification of embryos injected as in B,D. Arrows indicate nuclei stained with X-Gal (blue). (G-J) Dorsal (G,I) and ventral (H,J) views of embryos injected as in B with Syn4 mRNA. No ectopic expression of MyoD (0%) or Xbra (0%) was observed. Inset in H shows injected fluorescein. (K-N) Animal cap (AC) assay for Sox2 (K,L) or Epk (M,N) expression. (K,M) Control caps express only Epk. (L,N) Syn4 mRNA-injected animal caps express Sox2 and downregulate Epk.

The FGF/MAPK signalling pathway is required for neural induction by Syn4

As Syn4 is a proteoglycan that binds growth factors, including FGF, through its extracellular GAG chains, but can also modulate intercellular signalling through its intracellular domain (Couchman, 2003), we tested a set of deletion constructs of Syn4 for neuralising ability. mRNA for each of these constructs was injected into the A4 blastomere of a 32-cell stage embryo and their ability to induce neural tissue was compared with that of full-length Syn4 mRNA. Deletion of the GAG-binding domain (Syn4ΔGAG) caused a modest, but reproducible, loss of neural induction ability (see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material), whereas deletion of the intracellular domain (Syn4ΔCytCherry) had a stronger effect (see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material). Together, these experiments implicate both the extracellular and intracellular domains of Syn4 in neural induction (see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material).

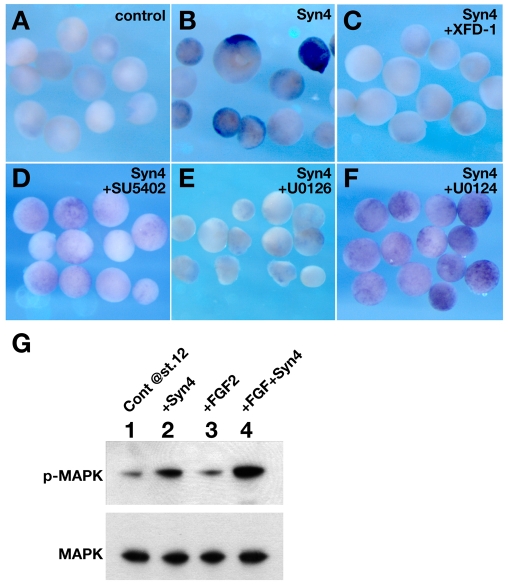

Syn4 is known to modulate FGF activity (Tkachenko et al., 2004) and FGF is involved in neural induction (Fuentealba et al., 2007; Kuroda et al., 2005; Streit et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 2000). This raises the possibility that the effects of Syn4 gain- and loss-of-function are due to interference with FGF signalling. Neural induction by Syn4 in animal caps (Fig. 4A,B) was inhibited by co-injection of a dominant-negative FGF receptor (XFD-1) (Fig. 4C), as well as by the presence of the FGF receptor inhibitor SU5402 (Fig. 4D) or the MEK inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 4E), but not by the inactive analogue U0124 (Fig. 4F). Moreover, Syn4 induced phosphorylation of MAPK in animal caps cultured to stage 12.5 (the stage at which neural induction was analysed) (Fig. 4G, lanes 1, 2). Note that although FGF promotes MAPK phosphorylation at early gastrula stages (Sivak et al., 2005), this effect is not maintained when the animal caps are cultured until stage 12.5 (Fig. 4G, compare lanes 1 and 3). However, a high level of MAPK phosphorylation was observed at these stages in animal caps treated with FGF and Syn4 (Fig. 4G, lane 4). Together, these results indicate that Syn4 cooperates with FGF to activate the FGF/MAPK signalling pathway and that this activation is required for neural induction.

Fig. 4.

The FGF/MAPK pathway is required for neural induction by Syn4. (A-F) Sox2 expression analysed by whole-mount in situ hybridisation in Xenopus animal caps. (A) Control caps. No Sox2 expression. (B) Syn4-injected caps express Sox2. (C) Co-injection of Syn4 and a dominant-negative form of FGF receptor 1 (XFD-1) inhibits Sox2 expression. (D) Syn4-injected caps treated with 40 μM SU5402 (in DMSO) do not show Sox2 expression. (E) Syn4-injected caps treated with 80 μM U0126 do not express Sox2. (F) Syn4-injected caps treated with 80 μM U0124 show expression of Sox2.(G) Animal caps were injected as indicated (Cont, control) and samples taken for western blot analysis of MAPK phosphorylation at the equivalent of stage 12. Antibodies against MAPK or phosphorylated MAPK (p-MAPK) can recognise both p42 and p44 as a single band. Each experiment was repeated three times with at least 50 animal caps.

Syn4 inhibits the PLC-PKC pathway

The above results implicate the extracellular GAG-binding domain of Syn4 in neural induction. However, other experiments presented above revealed that deletion of the intracellular domain of Syn4 has an even stronger effect on neural induction.

The PLC/PKC pathway is involved in both FGF and Syn4 signalling (Simons and Horowitz, 2001; Sivak et al., 2005). Moreover, PKC has been implicated in neural induction (Otte et al., 1988; Otte et al., 1989; Otte et al., 1990; Otte et al., 1991; Otte and Moon, 1992), although this has never been clearly connected with FGF or BMP signalling. Activation of the PLC/PKC pathway by FGF leads to translocation of PKCδ to the membrane (Kinoshita et al., 2003; Sivak et al., 2005). We tested whether this change in localisation is Syn4 dependent. PKCδ-GFP distribution was diffuse in untreated animal caps (Fig. 5A-C), but on addition of the PKC activator, phorbol ester (PMA), or of FGF2, the fusion construct translocated to the cell membrane and colocalised with membrane Cherry (Fig. 5G-L). Strikingly, overexpression of Syn4 not only failed to promote PKCδ-GFP membrane translocation (Fig. 5D-F), but also inhibited translocation triggered by FGF2 (Fig. 5M-O). These results suggest that Syn4 modulates FGF signalling by inhibiting PKCδ activity.

PKCδ and PKCα as downstream effectors of Syn4 during neural induction

As Syn4 inhibits PKCδ activity and induces neural tissue, we asked whether direct inhibition of PKCδ is sufficient to neuralise ventral ectoderm. Injection of a dominant-negative PKCδ RNA (DN-PKCδ) (Kinoshita et al., 2003) into the A4 blastomere induced Sox2 (Fig. 6A), whereas injection of wild-type PKCδ mRNA into the endogenous neural plate region led to inhibition of neural plate marker expression (see Fig. S1C,E in the supplementary material). Furthermore, neural induction by Syn4 mRNA was inhibited by co-injection of PKCδ mRNA (Fig. 6B). These results support the conclusion that Syn4 inhibits PKCδ expression and that this inhibition is required for the neuralising activity of Syn4.

To understand more about the mechanism of neural induction by Syn4, we analysed some candidate downstream effectors of this PKCδ inhibition. It has been shown in many systems that PKCδ and PKCα activities repress each other (Kinoshita et al., 2003; Choi and Han, 2002) and that PKCα is implicated in neural induction (Otte et al., 1988). Consistent with these findings, we found that injection of PKCα mRNA into the A4 blastomere induces Sox2 (Fig. 6C) and inhibits EpK (see Fig. S1H in the supplementary material), whereas co-injection of PKCδ mRNA (Fig. 6D) blocks this process.

In conclusion, our data support the hypothesis that activation of PKCα and inhibition of PKCδ promote neural induction, and that these two kinases antagonise each other. The inhibition of PKCδ expression by Syn4 mRNA and the inhibition of PKCδ expression by PKCα mRNA prompted us to analyse the relationship between Syn4 and PKCα in neural induction. We found that the induction of Sox2 by PKCα mRNA (Fig. 6E) is inhibited by co-injection of Syn4 MO (Fig. 6F), whereas dominant-negative PKCα RNA blocks neural induction by Syn4 (Fig. 6G). Observations in cultured cells indicate that Syn4 recruits phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) and translocates PKCα to the membrane (Keum et al., 2004). We analysed the localisation of a PKCα-EGFP fusion protein that retains its neuralising activity when injected into ventral ectoderm (Fig. 6H). PKCα-EGFP expressed in animal caps showed a spontaneous membrane localisation that was not affected by co-injection with control MO (Fig. 6I-K). However, mosaic expression of Syn4 MO (cells labelled with an asterisk in Fig. 6L-N) led to a complete absence of PKCα-EGFP from the membrane, indicating that Syn4 is required for the activation of PKCα. We therefore propose that neural induction by Syn4 is mediated by activation of PKCα and that this activation requires Syn4.

Syn4 induces neural tissue in a MAPK- and PKCα-dependent manner. What is the link between the MAPK and PKCα activities? PKCα is known to activate MAPKs, including p38-MAPK, ERK and JNK (Mauro et al., 2002; Rucci et al., 2005; Seo et al., 2004; Skaletzrorowski et al., 2005; Wensheng, 2006). However, we found no evidence that neural induction by PKCα depends on MAPK. First, induction of Sox2 in animal caps by PKCα (Fig. 7A, lane 3) was not inhibited by the MEK inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 7A, lane 4), in spite of the strong inhibition of phosphorylated MAPK (p-MAPK in Fig. 7A, lane 4). Second, PKCα did not affect the phosphorylation of MAPK, as analysed by western blot (Fig. 7A,B). Therefore, our results do not support a direct link between MAPK activity and PKCα during neural induction, a discovery that prompted us to look for downstream effectors of PKCα in neural induction.

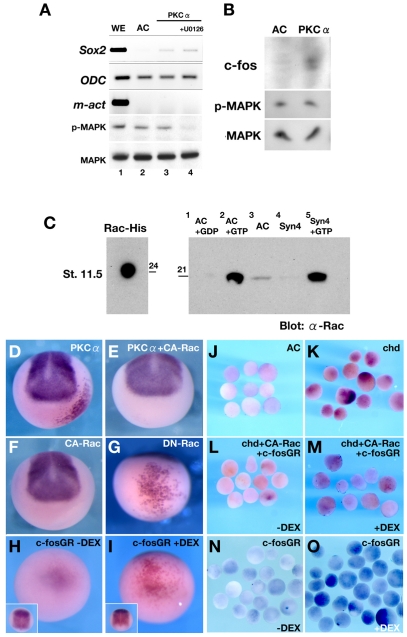

Fig. 7.

The PKC-dependent pathway of neural induction is mediated by the Rac/JNK/AP-1 pathway. (A) RT-PCR of the indicated genes using RNA from Xenopus whole embryos (WE, lane 1), animal caps (AC, lane 2), animal caps expressing PKCα (PKCα, lane 3) or animal caps expressing PKCα and treated with the inhibitor U0126 (+U0126, lane 4). Note that Sox2 is induced by PKCα even when MAPK is inhibited (lane 4). (B) Western blot of control- or PKCα-injected animal caps, detecting c-Fos, phosphorylated MAPK (p-MAPK) and MAPK. Neuralisation of the animal caps correlates with an increase in c-Fos levels, whereas p-MAPK is unchanged. (C) Rac activation assay. (Left) Rac1-His recombinant protein (24 kDa; 20 ng) was loaded and detected by anti-Rac antibody as a positive control. (Right) The same volume of reaction mix was loaded for each condition. Lane 1 (AC+GDP), negative control; lane 2 (AC+GTP), positive control that shows the total amount of Rac protein in the animal cap samples; lane 3 (AC), endogenous active Rac present in animal caps at stage 11.5; lane 4 (Syn4), endogenous active Rac present in animal caps at stage 11.5 injected with 500 pg of Syn4 mRNA (note that Syn4 abolishes endogenous Rac activity); lane 5 (Syn4+GTP), total amount of Rac protein after Syn4 injection. The experiment was repeated three times. (D-I) Whole-mount in situ hybridisation analysis of embryos injected, as indicated, into the A4 blastomere of 32-cell stage embryos. (D) Human (h) PKCα mRNA induces ectopic Sox2 expression (68%, n=92). (E) Co-injection of constitutively active Rac and hPKCα inhibits ectopic Sox2 expression (21% of induction, n=34). (F) Injection of constitutively active Rac does not induce Sox2 expression (0%, n=32). (G) Dominant-negative Rac1 mRNA induces ectopic ventral Sox2 expression (90%, n=40). (H,I) Ventral view of embryos injected with c-Fos-GR mRNA and activated with dexamethasone (DEX) at stage 10.5. Ectopic Sox2 expression is observed only after DEX treatment (I), being absent when no DEX is added (H; inset shows dorsal side). (J-O) In situ hybridisation for Sox2 in animals caps. (J) Control animal caps show no Sox2 expression. (K) Animal caps from embryos injected with chordin (chd) mRNA show Sox2 expression. (L) Animal caps from embryos injected with chordin, constitutive Rac and c-Fos-GR mRNA but without adding DEX. Activation of Rac leads to inhibition of Sox2. (M) Similar to L, but c-Fos-GR is activated by DEX treatment. Rescue of Sox2 expression is observed. (N) Injection of c-Fos-GR mRNA, but without adding DEX. (O) c-Fos-GR-injected animal caps activated with DEX show an increase in Sox2 expression.

Rac/AP-1 as downstream effectors of PKCα during neural induction

We have recently shown that Syn4 is a repressor of the small GTPase Rac during neural crest migration in vivo (Matthews et al., 2008), whereas the Syn4/PKC/Rac/RhoA signalling complex appears to be a key regulator of cell migration in vitro (Couchman, 2003). Could a similar pathway be involved in neural induction? Our results showed that the normal levels of Rac activity found in a control animal cap (Fig. 7C, AC lane 2) are strongly inhibited by expression of Syn4 (Fig. 7C, Syn4 lane 4). Furthermore, our data suggest that the inhibition of Rac activity by PKCα is a requirement for neural induction. Neural induction by PKCα misexpression (Fig. 7D) was inhibited by co-injection of a constitutively active form of Rac (Fig. 7E,F). In addition, expression of active Rac in the neural plate led to inhibition of the endogenous neural plate (see Fig. S1D,F in the supplementary material). By contrast, injection of a dominant-negative form of Rac into the A4 blastomere strongly induced Sox2 (Fig. 7G), supporting the hypothesis that inhibition of Rac activity by Syn4/PKCα can induce neural tissue.

Hitherto, the Syn4/PKC/RhoA/Rac pathway has only been implicated in cell migration. Our data suggest that it also has an important role in cell specification. What could be the downstream target of Rac that is required for neural plate development? Rac is known to activate the c-Jun NH2 kinase (JNK), which promotes dimerisation of c-Jun and downregulates formation of the AP-1 complex (c-Jun/c-Fos) (Boyle et al., 1991). Previous reports suggest that the AP-1 complex is required for neural induction and that it binds directly to the promoter of the neural plate gene Zic3 during this inductive process (Leclerc et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2004). One hypothesis is that the PKCα/Rac pathway facilitates formation of the heterodimeric AP-1 complex (c-Fos/c-Jun) during neural induction. To test this hypothesis, we constructed a hormone-inducible derivative of Xenopus c-Fos that cannot homodimerise (Halazonetis et al., 1988; Nakabeppu et al., 1988); it will only form the heterodimer c-Fos/c-Jun when c-Fos is overexpressed, and is therefore expected to increase formation of the AP-1 complex. A similar approach has been described using c-Fos-ER to activate AP-1 in fibroblasts (Reichmann et al., 1992). We made a construct containing the Xenopus c-Fos gene fused to the human glucocorticoid receptor (GR; see Materials and methods). Ectopic expression of c-Fos-GR was achieved by injecting mRNA into the A4 blastomere and adding dexamethasone at stage 10.5, which induced Sox2 (Fig. 7H), whereas embryos that were not treated with dexamethasone did not upregulate Sox2 (Fig. 7I). In addition, western blot analysis revealed that PKCα increases c-Fos protein levels in animal caps (Fig. 7B).

Overexpression of c-Fos-GR was also used to rescue neural induction inhibited by activation of Rac. Animal caps injected with chordin mRNA expressed Sox2 (Fig. 7J,K), and, as expected, this induction was inhibited by expression of activated Rac (Fig. 7L). However, this inhibition of neural induction could be reversed by activation of the c-Fos-GR construct with dexamethasone (Fig. 7M). It should be noted that activation of c-Fos-GR is sufficient to neuralise the animal caps (Fig. 7N,O). In conclusion, our data are consistent with the idea that PKCα promotes the formation of AP-1 complexes that are required for neural induction through the inhibition of Rac.

DISCUSSION

Here we demonstrate that Syn4 plays an important role in neural induction and identify the signalling pathways required for neural induction by Syn4. Inhibition of Syn4 in the ectoderm of whole embryos or in animal caps leads to strong inhibition of neural plate markers. Overexpression of Syn4 in ventral epidermis or animal caps is sufficient to induce neural tissue. At least two parallel signalling pathways are involved in this neural induction: FGF/MAPK and PKC/Rac/AP-1. We propose that the localised expression of Syn4 in the neural plate is required to modulate these two pathways.

The role of Syn4 during Xenopus development has recently been analysed, revealing its key role as a new element of the PCP pathways during convergent extension and neural crest migration (Muñoz et al., 2006; Matthews et al., 2008). The apparent lack of any effect on neural plate or neural crest induction in these previous reports is likely to be due to the targeting of different regions of the embryo. In order to see the effect of Syn4 MO on neural induction, the injection has to be targeted to the prospective neuroectoderm, whereas injections into prospective mesoderm, as published by Muñoz et al. (Muñoz et al., 2006), lead to convergent extension defects. In addition, Syn4 is expressed in neural crest cells just before their migration starts, once they are already specified (Matthews et al., 2008) (and this work), which explains why the MO does not affect neural crest induction. Taken together, these previous publications and the data presented here indicate that the same signalling molecule can be involved in induction and cell migration at different times during development.

Although early findings implicating FGF in neural induction (Lamb and Harland, 1995; Alvarez et al., 1998; Hongo et al., 1999) were controversial, the evidence is now strong that FGF is indeed involved in the induction of neural tissue (Sasai et al., 1994; Smith et al., 1993; Launay et al., 1996; Linker and Stern, 2004; Pera et al., 2003; Streit et al., 1998; Streit et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 2000). Moreover, FGF contributes to the inhibition of BMP signalling, at least in part by phosphorylation of Smad1 during neural induction (Fuentealba et al., 2007; Kuroda et al., 2005).

Syn4 modulates FGF signalling through its extracellular domain (containing the GAG-binding region, which will present heparin sulphates to which FGF is expected to bind) and by an effect on the transduction of intracellular signals (Hou et al., 2007; Iwabuchi and Goetinck, 2006; Horowitz et al., 2002). Our data support the idea that FGF is required for neural induction and that Syn4 is a likely modulator, by showing that the inhibition of FGF receptor and of MAPK activity impair neural induction by Syn4. Syn4 could act as a co-receptor of the FGF receptor (Hou et al., 2007) or as a presenter of the FGF ligand, through binding of FGF to the GAG side-chains, to facilitate the activation of FGF receptor (Fig. 8A).

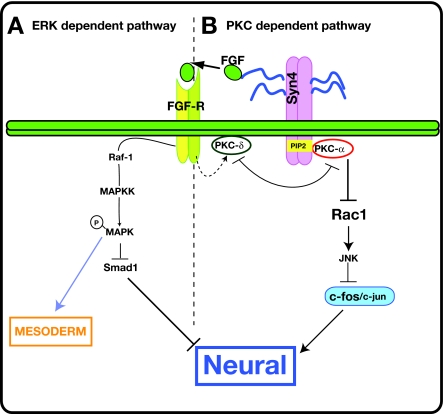

Fig. 8.

Model of neuralisation by Syn4. (A) The Syn4/ERK-dependent pathway. The glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in the extracellular domain of Syn4 activate the FGF/MAPK pathway. The activation of this pathway can lead to mesoderm induction, but also contributes to neural induction, probably though the inhibition of Smad1. (B) The Syn4/PKC-dependent pathway. The intracellular domain of Syn4 inhibits PKCδ and activates PKCα. The inhibition of PKCδ is required for the recruitment of PKCα to the membrane and its binding to Syn4. Activated PKCα inhibits Rac activity. Rac activates JNK, which phosphorylates c-Jun and inhibits the formation of the c-Jun/c-Fos dimers that form part of the AP-1 transcriptional regulator complex. Thus, the inhibition of Rac by Syn4/PKCα leads to the activation of the AP-1 complex that controls the transcription of preneural genes

However, Syn4 also plays a separate role in neural induction involving PKC (Fig. 8B). We propose that this involves inhibition of PKCδ and activation of PKCα, and that PKCα is an inhibitor of the small GTPase Rac. Since the BMP-inhibiting effects of FGF act through MAPK (Kuroda et al., 2005), this pathway could account for the BMP-inhibition-independent role of FGF signalling in neural induction (Linker and Stern, 2004; Delaune et al., 2005; de Almeida et al., 2008). Rac is a well-known regulator of cell migration that acts by controlling actin polymerisation, but has not previously been implicated in neural induction. Evidence that Rac can control JNK activity (Chen et al., 2006; Habas et al., 2003) suggested the hypothesis that Syn4/PKCα might inhibit Rac activity by an increase in AP-1 (c-Fos/c-Jun) activity that is mediated through inhibition of JNK.

The AP-1 transcription factor complex incorporates c-Jun, c-Fos and ATF protein dimers and mediates gene regulation in response to a plethora of physiological and pathological stimuli (Hess et al., 2004). The relative abundance of AP-1 subunits seems to play a key role in gene regulation (Eferl and Wagner, 2003). c-Fos cannot dimerise and requires c-Jun to be active (Eferl and Wagner, 2003). When c-Jun is phosphorylated by JNK it becomes latent and unable to bind to DNA (Boyle et al., 1991). Activation of JNK inhibits heterodimeric AP-1.

PKC activated by TPA (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate) dephosphorylates c-Jun and simultaneously increases AP-1 DNA-binding activity (Boyle et al., 1991). This is consistent with our results suggesting that Syn4/PKCα promotes the formation of the c-Fos/c-Jun complex (Fig. 8B). Additional support comes from the finding that overexpression of PKCα increases c-Fos levels in animal caps. Studies of the preneural gene Zic3 revealed that AP-1 binds directly to the Zic3 promoter rather than to the c-Jun homodimer (Lee et al., 2004). Taken together, these data suggest that during neural induction, Syn4/PKCα might inhibit Rac to minimise JNK activity, facilitating formation of the c-Fos/c-Jun (AP-1) complex.

A role for PKCα in neural induction was first suggested almost 20 years ago (Otte et al., 1988; Otte et al., 1989; Otte et al., 1990; Otte et al., 1991; Otte and Moon, 1992) but had never been connected with the signalling pathways now known to be involved in neural induction. It was originally shown that PKCα is activated and translocated to the membrane during neural induction, and it was suggested that this is required to confer neural competence on the ectoderm (Otte et al., 1988; Otte et al., 1989; Otte et al., 1990; Otte et al., 1991; Otte and Moon, 1992). We have confirmed and extended these observations by showing that expression of PKCα in ventral ectoderm or in animal caps can act as a neuralising signal and that PKCα activity is regulated by interactions with Syn4 and PKCδ. PKCδ appears to work as a repressor of PKCα, whereas Syn4 appears to be required for PKCα activity; however, we also show that PKCα is required for the neuralising activity of Syn4. Thus, our finding allows us to propose a link between the PKC and FGF pathways, both of which have been identified previously as being involved in neural induction.

These observations have parallels in studies of migrating cells. Syn4 interacts with PIP2, and this stabilises the oligomeric structure of Syn4 and promotes the association of PKCα and Syn4 (Oh et al., 1997a; Oh et al., 1997b; Horowitz and Simons, 1998; Lim et al., 2003); the catalytic domain of PKCα binds to the cytoplasmic domain of Syn4, and PKCα is `superactivated' (Lim et al., 2003; Murakami et al., 2002). This interaction between PKCα and Syn4 provides a satisfactory explanation for our observation that neural induction by Syn4 requires PKCα and vice versa. In addition, during cell migration, PKCδ phosphorylates Syn4, decreases its affinity for PIP2 and abolishes its capacity to activate PKCα (Couchman et al., 2002; Murakami et al., 2002). We have found a similar negative regulation between PKCα and PKCδ during early neural plate development.

Despite several previous reports demonstrating direct phosphorylation of MAPK by PKCα (Mauro et al., 2002; Seo et al., 2004), we found no evidence that the PKC and MAPK pathways interact during neural induction other than indirectly, through Syn4. Neuralisation by PKCα is evidently MAPK-independent and PKCα does not affect MAPK activity. Another possibility is that Rac can affect MAPK signalling via PAK-MEK interactions, the amino acids T292 and S298 of MEK1 being essential for PAK-dependent ERK activity (Eblen et al., 2002). However, T292 is not conserved in Xenopus MEK1 (not shown), which could explain the absence of this regulatory pathway.

During cell migration, targets of the PKC pathway include small GTPases that control cytoskeletal organisation and adhesion to the extracellular matrix (Ridley et al., 2003). Our results suggest that Syn4/PKCα inhibits Rac activity during neural induction, as it does in migrating cells (Bass et al., 2007; Matthews et al., 2008). Expression of a dominant-negative Rac neuralises ventral ectoderm strongly, whereas activation of Rac inhibits neural induction by PKCα. However, activation of Rac in ventral ectoderm has no effect on neural plate markers, but induces neural crest markers (not shown), supporting recent reports of induction of neural crest by Rac/Rho activities (Broders-Brondon et al., 2007; Guemar et al., 2007).

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/136/4/575/DC1

Supplementary Material

We thank M. Sargent, C. Stern and C. Linker for comments on the manuscript; J. Couchman for the PKCα constructs; J.-K. Han for the pCS2+-human PKCα clone; N. Kinoshita for PKCδ constructs; and Oh and P. Kyung for the PKCα-EGFP construct; and NIBB Xenopus Resources (Japan) for cDNAs. This work was supported by MRC and BBSRC grants to R.M. and by the Uehara Memorial Foundation to S.K. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

References

- Alvarez, I. S., Araujo, M. and Nieto, M. A. (1998). Neural induction in whole chick embryo cultures by FGF. Dev. Biol. 199, 42-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass, M. D., Roach, K. A., Morgan, M. R., Mostafavi-Pour, Z., Schoen, T., Muramatsu, T., Mayer, U., Ballestrem, C., Spatz, J. P. and Humphries, M. J. (2007). Syndecan-4-dependent Rac1 regulation determines directional migration in response to the extracellular matrix. J. Cell Biol. 177, 527-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernfield, M., Gotte, M., Park, P. W., Reizes, O., Fitzgerald, M. L., Lincecum, J. and Zako, M. (1999). Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 729-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, V., Hudson, C., Caillol, D., Popovici, C. and Lemaire, P. (2003). Neural tissue in ascidian embryos is induced by FGF9/16/20, acting via a combination of maternal GATA and Ets transcription factors. Cell 115, 615-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, W. J., Smeal, T., Defize, L. H., Angel, P., Woodgett, J. R., Karin, M. and Hunter, T. (1991). Activation of protein kinase C decreases phosphorylation of c-Jun at sites that negatively regulate its DNA-binding activity. Cell 64, 573-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broders-Bondon, F., Chesneau, A., Romero-Oliva, F., Mazabraud, A., Mayor, R. and Thiery, J. P. (2007). Regulation of XSnail2 expression by Rho GTPases. Dev. Dyn. 236, 2555-2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brule, S., Charnaux, N., Sutton, A., Ledoux, D., Chaigneau, T., Saffar, L. and Gattegno, L. (2006). The shedding of syndecan-4 and syndecan-1 from HeLa cells and human primary macrophages is accelerated by SDF-1/CXCL12 and mediated by the matrix metalloproteinase-9. Glycobiology 16, 488-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnaux, N., Brule, S., Hamon, M., Chaigneau, T., Saffar, L., Prost, C., Lievre, N. and Gattegno, L. (2005). Syndecan-4 is a signaling molecule for stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1)/CXCL12. FEBS J. 272, 1937-1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Stump, R. J., Lovicu, F. J. and McAvoy, J. W. (2006). A role for Wnt/planar cell polarity signaling during lens fiber cell differentiation? Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 17, 712-725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. C. and Han, J. K. (2002). Xenopus Cdc42 regulates convergent extension movements during gastrulation through Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway. Dev. Biol. 244, 342-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couchman, J. R. (2003). Syndecans: proteoglycan regulators of cell-surface microdomains? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 926-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couchman, J. R., Vogt, S., Lim, S. T., Lim, Y., Oh, E. S., Prestwich, G. D., Theibert, A., Lee, W. and Woods, A. (2002). Regulation of inositol phospholipid binding and signaling through syndecan-4. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49296-49303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida, I., Rolo, A., Batut, J., Hill, C., Stern, C. D. and Linker, C. (2008). Unexpected activities of Smad7 in Xenopus mesodermal and neural induction. Mech. Dev. 125, 421-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaune, E., Lemaire, P. and Kodjabachian, L. (2005). Neural induction in Xenopus requires early FGF signalling in addition to BMP inhibition. Development 132, 299-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eblen, S. T., Slack, J. K., Weber, M. J. and Catling, A. D. (2002). Rac-PAK signaling stimulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation by regulating formation of MEK1-ERK complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6023-6033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eferl, R. and Wagner, E. F. (2003). AP-1: a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 859-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba, L. C., Eivers, E., Ikeda, A., Hurtado, C., Kuroda, H., Pera, E. M. and De Robertis, E. M. (2007). Integrating patterning signals: Wnt/GSK3 regulates the duration of the BMP/Smad1 signal. Cell 131, 980-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves, L. M., Northrop, J. L., Potts, B. C., Krebs, E. G. and Kimelman, D. (1994). Fibroblast growth factor, but not activin, is a potent activator of mitogen-activated protein kinase in Xenopus explants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 1662-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunz, H. and Tacke, L. (1989). Neural differentiation of Xenopus laevis ectoderm takes place after disaggregation and delayed reaggregation without inducer. Cell Differ. Dev. 28, 211-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guemar, L., de Santa Barbara, P., Vignal, E., Maurel, B., Fort, P. and Faure, S. (2007). The small GTPase RhoV is an essential regulator of neural crest induction in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 310, 113-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habas, R., Dawid, I. B. and He, X. (2003). Coactivation of Rac and Rho by Wnt/Frizzled signaling is required for vertebrate gastrulation. Genes Dev. 17, 295-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halazonetis, T. D., Georgopoulos, K., Greenberg, M. E. and Leder, P. (1988). c-Jun dimerizes with itself and with c-Fos, forming complexes of different DNA binding affinities. Cell 55, 917-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland, R. M. (1994). Neural induction in Xenopus. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 4, 543-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, R. S., Lewellyn, A. L. and Maller, J. L. (1994). MAP kinase is activated during mesoderm induction in Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol. 163, 521-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess, J., Angel, P. and Schorpp-Kistner, M. (2004). AP-1 subunits: quarrel and harmony among siblings. J. Cell Sci. 117, 5965-5973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongo, I., Kengaku, M. and Okamoto, H. (1999). FGF signaling and the anterior neural induction in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 216, 561-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, A. and Simons, M. (1998). Phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic tail of syndecan-4 regulates activation of protein kinase Calpha. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 25548-25551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, A., Murakami, M., Gao, Y. and Simons, M. (1999). Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate mediates the interaction of syndecan-4 with protein kinase C. Biochemistry 38, 15871-15877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, A., Tkachenko, E. and Simons, M. (2002). Fibroblast growth factor-specific modulation of cellular response by syndecan-4. J. Cell Biol. 157, 715-725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, S., Maccarana, M., Min, T. H., Strate, I. and Pera, E. M. (2007). The secreted serine protease xHtrA1 stimulates long-range FGF signaling in the early Xenopus embryo. Dev. Cell 13, 226-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iemura, S., Yamamoto, T. S., Takagi, C., Uchiyama, H., Natsume, T., Shimasaki, S., Sugino, H. and Ueno, N. (1998). Direct binding of follistatin to a complex of bone-morphogenetic protein and its receptor inhibits ventral and epidermal cell fates in early Xenopus embryo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 9337-9342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo, R. V. (1998). Matrix proteoglycans: from molecular design to cellular function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 609-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabuchi, T. and Goetinck, P. F. (2006). Syndecan-4 dependent FGF stimulation of mouse vibrissae growth. Mech. Dev. 123, 831-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keum, E., Kim, Y., Kim, J., Kwon, S., Lim, Y., Han, I. and Oh, E. S. (2004). Syndecan-4 regulates localization, activity and stability of protein kinase C-alpha. Biochem. J. 378, 1007-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, N., Iioka, H., Miyakoshi, A. and Ueno, N. (2003). PKC delta is essential for Dishevelled function in a noncanonical Wnt pathway that regulates Xenopus convergent extension movements. Genes Dev. 17, 1663-1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama, S., Lupo, G., Ohta, K., Ohnuma, S., Harris, W. A. and Tanaka, H. (2006). Tsukushi controls ectodermal patterning and neural crest specification in Xenopus by direct regulation of BMP4 and X-delta-1 activity. Development 133, 75-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, H., Fuentealba, L., Ikeda, A., Reversade, B. and De Robertis, E. M. (2005). Default neural induction: neuralization of dissociated Xenopus cells is mediated by Ras/MAPK activation. Genes Dev. 19, 1022-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, T. M. and Harland, R. M. (1995). Fibroblast growth factor is a direct neural inducer, which combined with noggin generates anterior-posterior neural pattern. Development 121, 3627-3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launay, C., Fromentoux, V., Shi, D. L. and Boucaut, J. C. (1996). A truncated FGF receptor blocks neural induction by endogenous Xenopus inducers. Development 122, 869-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc, C., Duprat, A. M. and Moreau, M. (1999). Noggin upregulates Fos expression by a calcium-mediated pathway in amphibian embryos. Dev. Growth Differ. 41, 227-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. Y., Lee, H. S., Moon, J. S., Kim, J. I., Park, J. B., Lee, J. Y., Park, M. J. and Kim, J. (2004). Transcriptional regulation of Zic3 by heterodimeric AP-1(c-Jun/c-Fos) during Xenopus development. Exp. Mol. Med. 36, 468-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S. T., Longley, R. L., Couchman, J. R. and Woods, A. (2003). Direct binding of syndecan-4 cytoplasmic domain to the catalytic domain of protein kinase C alpha (PKC alpha) increases focal adhesion localization of PKC alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 13795-13802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linker, C. and Stern, C. D. (2004). Neural induction requires BMP inhibition only as a late step, and involves signals other than FGF and Wnt antagonists. Development 131, 5671-5681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, H. K., Marchant, L., Carmona-Fontaine, C., Kuriyama, S., Larrain, J., Holt, M. R., Parsons, M. and Mayor, R. (2008). Directional migration of neural crest cells in vivo is regulated by Syndecan-4/Rac1 and non-canonical Wnt signaling/RhoA. Development 135, 1771-1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro, A., Ciccarelli, C., De Cesaris, P., Scoglio, A., Bouche, M., Molinaro, M., Aquino, A. and Zani, B. M. (2002). PKCalpha-mediated ERK, JNK and p38 activation regulates the myogenic program in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. J. Cell Sci. 115, 3587-3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody, S. A. (1987). Fates of the blastomeres of the 32-cell-stage Xenopus embryo. Dev. Biol. 122, 300-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, R., Moreno, M., Oliva, C., Orbenes, C. and Larraín, J. (2006). Syndecan-4 regulates non-canonical Wnt signalling and is essential for convergent and extension movements in Xenopus embryos. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 492-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Sanjuan, I. and Brivanlou, A. H. (2002). Neural induction, the default model and embryonic stem cells. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 271-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, M., Horowitz, A., Tang, S., Ware, J. A. and Simons, M. (2002). Protein kinase C (PKC) delta regulates PKCalpha activity in a Syndecan-4-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 20367-20371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakabeppu, Y., Ryder, K. and Nathans, D. (1988). DNA binding activities of three murine Jun proteins: stimulation by Fos. Cell 55, 907-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport, J. and Kirschner, M. (1982). A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: I. Characterization and timing of cellular changes at the midblastula stage. Cell 30, 675-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop, P. D. and Faber, J. (1967). Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin). Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing.

- Oelgeschläger, M., Kuroda, H., Reversade, B. and De Robertis, E. M. (2003). Chordin is required for the Spemann organizer transplantation phenomenon in Xenopus embryos. Dev. Cell 4, 219-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, E. S., Woods, A. and Couchman, J. R. (1997a). Multimerization of the cytoplasmic domain of syndecan-4 is required for its ability to activate protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 11805-11811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, E. S., Woods, A. and Couchman, J. R. (1997b). Syndecan-4 proteoglycan regulates the distribution and activity of protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 8133-8136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte, A. P. and Moon, R. T. (1992). Protein kinase C isozymes have distinct roles in neural induction and competence in Xenopus. Cell 68, 1021-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte, A. P., Koster, C. H., Snoek, G. T. and Durston, A. J. (1988). Protein kinase C mediates neural induction in Xenopus laevis. Nature 334, 618-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte, A. P., van Run, P., Heideveld, M., van Driel, R. and Durston, A. J. (1989). Neural induction is mediated by cross-talk between the protein kinase C and cyclic AMP pathways. Cell 58, 641-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte, A. P., Kramer, I. M., Mannesse, M., Lambrechts, C. and Durston, A. J. (1990). Characterization of protein kinase C in early Xenopus embryogenesis. Development 110, 461-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte, A. P., Kramer, I. M. and Durston, A. J. (1991). Protein kinase C and regulation of the local competence of Xenopus ectoderm. Science 251, 570-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pera, E. M., Ikeda, A., Eivers, E. and De Robertis, E. M. (2003). Integration of IGF, FGF, and anti-BMP signals via Smad1 phosphorylation in neural induction. Genes Dev. 17, 3023-3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo, S., Sasai, Y., Lu, B. and De Robertis, E. M. (1996). Dorsoventral patterning in Xenopus: inhibition of ventral signals by direct binding of chordin to BMP-4. Cell 86, 589-598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichmann, E., Schwarz, H., Deiner, E. M., Leitner, I., Eilers, M., Berger, J., Busslinger, M. and Beug, H. (1992). Activation of an inducible c-FosER fusion protein causes loss of epithelial polarity and triggers epithelial-fibroblastoid cell conversion. Cell 71, 1103-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, A. J., Schwartz, M. A., Burridge, K., Firtel, R. A., Ginsberg, M. H., Borisy, G., Parsons, J. T. and Horwitz, A. R. (2003). Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science 302, 1704-1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C. D., Archer, T. C., Cunningham, D. D., Grammer, T. C. and Casey, E. M. (2008). Sox3 expression is maintained by FGF signaling and restricted to the neural plate by Vent proteins in the Xenopus embryo. Dev. Biol. 313, 307-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucci, N., DiGiacinto, C., Orru, L., Millimaggi, D., Baron, R. and Teti, A. (2005). A novel protein kinase C alpha-dependent signal to ERK1/2 activated by alphaVbeta3 integrin in osteoclasts and in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. J. Cell Sci. 118, 3263-3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasai, Y., Lu, B., Steinbeisser, H., Geissert, D., Gont, L. K. and De Robertis, E. M. (1994). Xenopus chordin: a novel dorsalizing factor activated by organizer-specific homeobox genes. Cell 79, 779-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, S. M. and Sargent, T. D. (1989). Development of neural inducing capacity in dissociated Xenopus embryos. Dev. Biol. 134, 263-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo, H. R., Kwan, Y. W., Cho, C. K., Bae, S., Lee, S. J., Soh, J. W., Chung, H. Y. and Lee, Y. S. (2004). PKCalpha induces differentiation through ERK1/2 phosphorylation in mouse keratinocytes. Exp. Mol. Med. 36, 292-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons, M. and Horowitz, A. (2001). Syndecan-4-mediated signalling. Cell Signal. 13, 855-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivak, J. M., Petersen, L. F. and Amaya, E. (2005). FGF signal interpretation is directed by Sprouty and Spred proteins during mesoderm formation. Dev. Cell 8, 689-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaletzrorowski, A., Eschert, H., Leng, J., Stallmeyer, B., Sindermann, J., Pulawski, E. and Breithardt, G. (2005). PKC δ-induced activation of MAPK pathway is required for bFGF-stimulated proliferation of coronary smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 67, 142-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W. C., Knecht, A. K., Wu, M. and Harland, R. M. (1993). Secreted noggin protein mimics the Spemann organizer in dorsalizing Xenopus mesoderm. Nature 361, 547-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, C. (2005). Neural induction: old problem, new findings, yet more questions. Development 132, 2007-2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit, A., Lee, K. J., Woo, I., Roberts, C., Jessell, T. M. and Stern, C. D. (1998). Chordin regulates primitive streak development and the stability of induced neural cells, but is not sufficient for neural induction in the chick embryo. Development 125, 507-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit, A., Berliner, A. J., Papanayotou, C., Sirulnik, A. and Stern, C. D. (2000). Initiation of neural induction by FGF signalling before gastrulation. Nature 406, 74-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahinci, E. and Symes, K. (2003). Distinct functions of Rho and Rac are required for convergent extension during Xenopus gastrulation. Dev. Biol. 259, 318-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannahill, D., Isaacs, H. V., Close, M. J., Peters, G. and Slack, J. M. (1992). Developmental expression of the Xenopus int-2 (FGF-3) gene: activation by mesodermal and neural induction. Development 115, 695-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko, E. and Simons, M. (2002). Clustering induces redistribution of syndecan-4 core protein into raft membrane domains. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 19946-19951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko, E., Lutgens, E., Stan, R. V. and Simons, M. (2004). Fibroblast growth factor 2 endocytosis in endothelial cells proceed via syndecan-4-dependent activation of Rac1 and a Cdc42-dependent macropinocytic pathway. J. Cell Sci. 117, 3189-3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, D. C. and Hemmati-Brivanlou, A. (1997). Neural induction in Xenopus laevis: evidence for the default model. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 7, 7-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen-sheng, W. (2006). Protein kinase C α trigger Ras and Raf-independent MEK/ERK activation for TPA-induced growth inhibition of human hepatoma cell HepG2. Cancer Lett. 239, 27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S. I., Graziano, E., Harland, R., Jessell, T. M. and Edlund, T. (2000). An early requirement for FGF signalling in the acquisition of neural cell fate in the chick embryo. Curr. Biol. 10, 421-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods, A. and Couchman, J. R. (2001). Syndecan-4 and focal adhesion function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 578-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.