Abstract

Echolocating bats are known to continuously generate high frequency sonar pulses and listen to the reflecting echoes to localize objects and orient in the environment. However, silent behavior has been reported in a recent paper, which demonstrated that the big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) can fly a relative long distant (0.6 to 8 m) without echolocating when flying with another conspecific in a large flight room.1 Methodology and conclusion developed in this study have the potential for further experimental design to answer the question of how millions of bats navigate and orient in cohesive groups. In addition, the discovery of silent behavior suggests the possible use of cooperative sonar in echolocating animals.

Key words: bats, echolocation, eavesdropping, cooperative sonar

Introduction

Many animals in nature aggregate in large numbers and travel together with conspecifics, such as schools of fish, flocks of birds and swarms of insects, because of advantages in foraging and migrating with others.2 Many echolocating bat species are gregarious and often form a large group when flying out of their roost at dusk. For example, over one million Brazilian free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) have been observed to emerge from the roost within two hours.3 This remarkable group behavior raises many questions in bat research: How does an individual echolocating bat sort its vocalizations and echoes from those of conspecifics to orient among millions of others? How does a group of bats move coherently along the same direction? Does a bat in a group function individually or coordinate with other group members? A recent research finding from a laboratory study of free-flying big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus) may shed a light on these questions.1

The Discovery of Silent Behavior in Echolocating Bats

We recently uncovered a surprising behavior in echolocating bats, namely silence, when the animals flew in pairs.1 The prevalence of silent behavior depended on the spatial separation between the two bats and the similarity of their calls when they flew alone. When bats flew less than one meter apart, silent behavior occurred as much as 76% of the time (mean of 40% across seven pairs). This value dropped to about 20% when bats flew further than one meter apart. In addition, the more similar two bats' calls were during baseline recordings, the more silent behavior they exhibited when they were paired.

Silent behavior in echolocating bats was only recently documented, because of the technical challenge of assigning calls to the vocalizing individual when flying with others. Current devices used in recording bat vocalizations cannot discriminate each call and assign it to the vocalizing individual bat automatically, because a microphone placed within a few meters of two free-flying big brown bats will pick up a string of calls that could be produced by one bat, the other bat, or both. Our analysis method allowed us to assign echolocation calls to individual vocalizing bats when two individuals were paired in the same large flight room.1 We used more than one microphone (spaced about 1–2 meters apart), and measured the arrival time of the bats' calls at each of the microphones, while we simultaneously tracked the 3-D position of the bats using video. When a call is accurately assigned to the bat that produced it, the travel time difference between two microphones, estimated from the 3-D position data, is equal to the actual difference measured from the signal arrival times at the spatially separated microphones.

Methodology to Study Vocal Behavior of Bats Flying in Groups

The method used to sort and assign calls to the vocalizing animal in the two-bat condition can be extended to a limited number of bats, but can hardly be applied to millions of bats. Instead, other techniques could be utilized to record echolocation and flight data in a situation with extremely large numbers of bats. Scientists have used thermal cameras to capture the emergence of bat groups from roosts and track the flight trajectory of individual bats.4 Such thermal camera images would have to be synchronized to specialized microphone recordings taken from the flying bats. Telemetry microphones, a newly developed technology,5 could make it feasible to record echolocation calls generated by many individuals flying with millions of other bats.

Silent Behavior and Cooperative Sonar

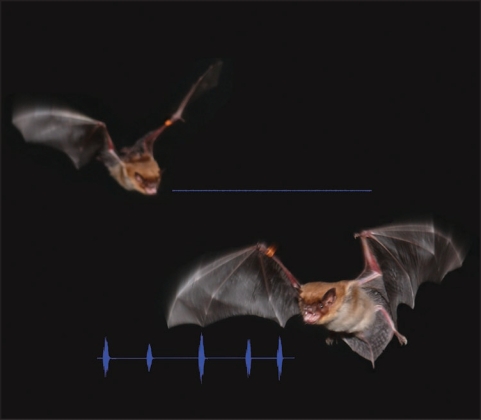

Previous studies have shown that several echolocating bat species adjust their echolocation call frequencies to avoid signal jamming from conspecifics.6–8 The newly discovered strategy, silence, reveals that the big brown bat sometimes stops its echolocation to avoid signal interference from others (Fig. 1).1 This jamming avoidance function of silent behavior is suggested by the observations that the bat showed more silent behavior when inter-bat spacing was short and when it was paired with an individual whose signals were similar to its own.

Figure 1.

Two big brown bats, Eptesicus fuscus, fly together in a large laboratory room equipped with high speed stereo video and sound recording equipment. One bat ceases production of its echolocation calls to avoid sonar jamming with the other individual. Photograph courtesy of Jessica Nelson.

The discovery of silent behavior also implies the possibility that the bat may use another individual's echolocation to substitute the function of its own echolocation. Echolocating animals have been reported to use eavesdropping to track food sources, to discriminate objects or to orient in the environment. A silent bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) recognizes various objects by listening to another dolphin's echolocation at a close distance.9 A group of Hawaiian spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris) passively listens to one or a few group members' echolocation signals to orient in the ocean.10 Wild rough-toothed dolphins (Steno bredanensis) that swim in synchronized formation tend to produce fewer echolocation calls than those that swim in asynchronous formation, which suggests that dolphins swimming in groups may use other individuals' echolocation signals for orientation.11 In addition, an acoustic experiment has verified that a sonar receiver can use echo returns from another sonar transmitter.12 This result suggests the possibility that a passively listening animal can localize objects from sonar echoes generated by a neighbor under two conditions: first, the sonar source and the listener are closely spaced; second, the listener and the sonar source keep a fixed formation.

Echolocating bats can listen to echolocation calls made by conspecifics and use them to track food sources or find an occupied roost.13–15 The term eavesdropping is often applied to describe a listener extracting information from others in a communication network, and most studies on this topic have been in non-echolocating animals, such as birds, frogs, etc.16 The silent behavior in big brown bats suggests the possible use of cooperative sonar and eavesdropping in echolocating bats.12 Returning to the question posed above, “How does an echolocating bat sort its vocalizations and echoes from those of conspecifics to orient among millions of others?” the answer may be, “Silence.” Perhaps only a few bats in a large group generate echolocation calls and other members remain silent to avoid severe signal interference. However, this question must be answered through empirical studies, which could also attempt to determine how many vocalizing individuals in a group are sufficient to support group orientation.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Communicative & Integrative Biology E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cib/article/7107

References

- 1.Chiu C, Xian W, Moss CF. Flying in silence: echolocating bats cease vocalizing to avoid sonar jamming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13116–13121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804408105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parrish JK, Hamner WM. Animal Groups in Three Dimensions. Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betke M, Hirsh DE, Makris NC, McCracken GF, Procopio M, Hristov NI, et al. Thermal imaging reveals significantly smaller Brazilian free-tailed bat colonies than previously estimated. J Mammal. 2008;89:18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betke M, Hirsh DE, Bagchi A, Hristov NI, Makris NC, Kunz TH. Tracking large variable numbers of objects in clutter. Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Science Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Minneapolis, Minnesota. 2008:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiryu S, Hagino T, Riquimaroux H, Watanabe Y. Echo-intensity compensation in echo-locating bats (Pipistrellus abramus) during flight measured by a telemetry microphone. J Acoust Soc Am. 2007;121:1749–1757. doi: 10.1121/1.2431337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates ME, Stamper SA, Simmons JA. Jamming avoidance response of big brown bats in target detection. J Exp Biol. 2008;211:106–113. doi: 10.1242/jeb.009688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obrist MK. Flexible bat echolocation: The influence of individual, habitat and conspecifics on sonar signal design. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1995;36:207–219. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ulanovsky N, Fenton MB, Tsoar A, Korine C. Dynamics of jamming avoidance in echo-locating bats. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2004;271:1467–1475. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xitco MJ, Roitblat HL. Object recognition through eavesdropping: passive echolocation in bottlenose dolphins. Anim Learn Behav. 1996;24:355–365. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lammers MO, Au WW. Directionality in the whistles of Hawaiian spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris): a signal feature to cue direction of movement? Mar Mamm Sci. 2003;19:249–264. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotz T, Verfuß UK, Schnitzler HU. ‘Eavesdropping’ in wild rough-toothed dolphins (Steno bredanensis)? Biol Lett. 2006;2:6–7. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2005.0407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuc R. Object localization from acoustic emissions produced by other sonars. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;112:1753–1755. doi: 10.1121/1.1508792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barclay RMR. Interindividual use of echolocation calls: eavesdropping by bats. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1982;10:271–275. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balcombe JP, Fenton MB. Eavesdropping by bats: The influence of echolocation call design and foraging strategy. Ethology. 1988;79:158–166. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones G. Sensory ecology: echolocation calls are used for communication. Curr Biol. 2008;18:34–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janik VM. Underwater acoustic communication networks in marine mammals. In: McGregor P, editor. Animal Communication Networks. Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 390–415. [Google Scholar]