Abstract

An increasing body of literature considers the question of how mate choice is influenced by the social environment of the choosing individual (non-independent mate choice). For example, individuals may copy the mate choice of others. A very simple form of socially influenced mate choice, however, remained comparatively little investigated: choosing individuals may adjust their mate choice to the mere presence of rivals. Recent studies in our groups1–4 have examined this question. Using live bearing fish (mollies, Poecilia spp.) as a model, we could show that (a) males will copy the mate choice of other males,5 (b) males cease expressing mating preferences in the presence of a conspecific rival male,1,2 whereas (c) females copy each other's mate choice, but are otherwise not affected by an audience.3 (d) Most importantly, males, when presented with an audience (potential rival), first approached the previously non-preferred female, suggesting that males attempt to lead the rival away from their preferred mate, thereby exploiting male mate choice copying behavior.4 We discuss that these effects are best explained as male adaptations to reduce the risk of sperm competition in a highly dynamic mating system with frequent multiple mating.

Key words: audience effect, communication networks, mate choice, sexual selection, non-independent mate choice, sperm competition

Sexual selection theory often assumes that optimal mate choice is based on an inner representation of the best possible mate.6 However, several studies have shown that individuals copy the mate preferences of other individuals and use social cues for decision-making.7–10 Such studies provide compelling evidence that female and male mate choice is not independent, but influenced by social conditions. Consequently, mate choice decisions must be viewed not as dyadic interactions between a chooser and a chosen individual, but as parts of a network with multiple senders and receivers of information (Fig. 1),11 and signaling interactions are very complex. Obviously, animals observe interactions between other individuals and intercept the information transmitted. Even when only two individuals attempt to communicate directly, the presence of neighboring individuals can affect the behavior of the signaler and/or the receiver.12,13 Consequently, recent work has started using other experimental approaches, in addition to the classical binary choice test.

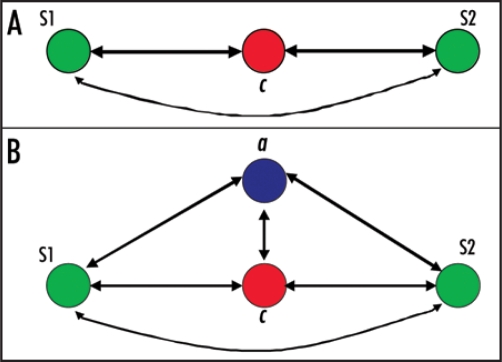

Figure 1.

Model of a simple communication network during (A) a binary preference test and (B) a preference test with an audience. S1, S2 refers to the stimuli, (c) refers to the chooser, (a) refers to the audience. The arrows indicate potential interactions. Several simple communication networks have been described as simultaneous communication networks.13

Most studies on information exchange in animal communication networks have either focused on (a) how an individual observing two or more other communicating individuals alters its own behavior or physiology14 in relation to the observed communication event (“eavesdropping”15–18) or (b) how the observing (“by-standing”) individual influences the behavior of a pair of communicating individuals (“audience effect”19,20).

Socially Influenced Mate Choice

In the context of mate choice, several studies have examined socially influenced (non-independent) mate choice of an observing individual in a communication network.9,10 For example, females may learn to evaluate the quality of males while eavesdropping on male-male interactions,15–18 or individuals may base their mate choice decisions on whether they had seen other members of their own sex sexually interact with a potential mating partner (mate choice copying21). Also, males of the live bearing fish Poecilia latipinna copy the mate choice of other males.5 Schlupp and Ryan5 argued that in live bearing fishes sexual attention by other males probably serves as an indicator that the female is in the receptive stage of her approximately monthly sexual cycle, during which time copulations are more likely to fertilize the female's oocytes.

It seems straightforward to assume that signaling and mate choice decisions will be adjusted under the risk of being watched by another individual. Consequently, mating decisions must be viewed as context-dependent. To date, however, audience effects have been examined primarily in a non-sexual context. For example, a female or a male audience may influence the intensity of aggressive male-male interactions.13,22 Given that mate choice in many species almost inevitably takes place in a social environment (i.e., in front of an audience), more effort is needed to examine whether and how the presence of an audience influences mate choice decisions.

Effect of an Audience on the Expression of Male Mating Preferences

In summary, when mating preferences are influenced by the mere presence of an observing individual, this represents a simple, but probably very widespread form of socially influenced mate choice (Fig. 1). Despite an increasing knowledge about the evolution of “innate” mating preferences (example in refs. 6 and 23), little is known so far about the expression of mating preferences in response to a social interaction network.12 In nature, communication during mate choice is rarely binary like in classical, standardized mate choice experiments (Fig. 1), but rather several individuals interact, and communication networks prevail. Understanding the role of the social environment for the expression of mating preferences will also be important to explain an evolutionary conundrum, namely, the maintenance of pronounced variation in the chosen sex in a given population despite apparently strong, directional sexual selection by mate choice (reviewed in ref. 24).

Do audience effects influence mate choice decisions in poeciliid fishes beyond mate copying? In one study,1 we examined if the presence of an audience—a conspecific male as a potential competitor—affects male mate choice in the Atlantic molly (P. mexicana), a small Mexican live bearing fish. Males were given an opportunity to choose between two females that were presented visually, and we observed whether their initial association preference would be altered when another (audience) male was present. Examining the influence of an audience on mate choice decisions in this set-up includes interactions between four individuals: the choosing (focal) male, two stimulus females, and the audience male (Fig. 2). All individuals could visually interact, but all except the focal male were confined to a defined location. Hence, the audience male could not approach the stimulus females to directly interact with them like in studies examining male mate choice copying.5 Males were given an opportunity to choose between a conspecific and a heterospecific female (P. formosa, a syntopic, sperm-dependent parthenogenetic species25) or a large vs. small conspecific female, and the males' association times near the two types of females were determined as an indicator of mate choice. During the second part of the tests we visually presented an audience male to the focal male, and we compared male association preferences between the two parts (Fig. 2).

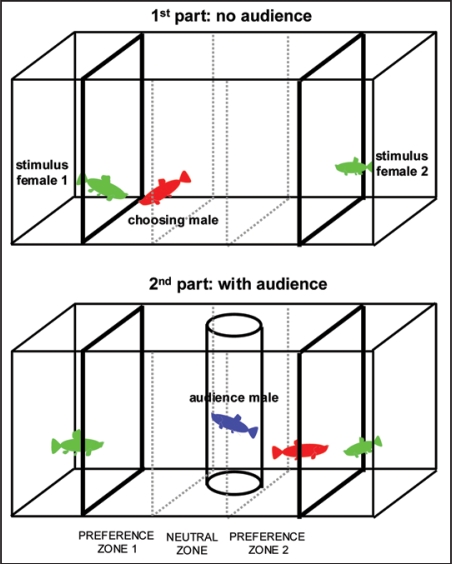

Figure 2.

Experimental set-up used to examine the effects of a visually presented audience on (male) mate choice decisions using simultaneous choice tests.1 During the first part of a trial, a focal male could choose between two simultaneously presented stimulus females. During the second part another (audience) male was visually presented in the neutral zone. For display purpose, fish are depicted at a supernatural size. The color code follows Figure 1.

In both experiments the focal males spent less time near the initially preferred female, and spent more time near the initially non-preferred female when we presented a conspecific audience male during the second part of the tests (Fig. 3). When we presented a heterospecific (Xiphophorus hellerii) male instead, the change in male preferences was significantly weaker. Male preferences were highly consistent when we presented no audience male during the second part of the tests. Very similar results were obtained when the behavior of the related Sailfin molly (P. latipinna) was examined.26

Figure 3.

The time P. mexicana males spent associating with one of the two females in simultaneous choice tests (A conspecific vs P. formosa stimulus females; B large vs small conspecific females). During the first part the male was alone in the test tank, during the second part an audience male was visually presented. In treatment 1 a conspecific male was used as audience male, in treatment 2 no audience male was presented (“control”), and in treatment 3, a swordtail male was the audience. Gray bars indicate time spent near the initially preferred female, open bars indicate time spent near the initially non-preferred female.1

This study highlights that the social environment indeed has an important effect on the expression of mate choice decisions, and even the mere visual presence of a conspecific audience can affect association preferences (as an indicator of mating preferences). Basically, three explanations seem possible: first, males may move away from the preferred female to avoid agonistic interactions when competing with a rival for the same female. Second, altering mate choice may just be a by-product of the focal males being diverted from mate choice (the “split-attention” hypothesis). Third, altering mate choice may be adaptive, e.g., because males avoid sperm competition.

Audience Effects: Adaptive or a Side Effect of Split-Attention?

This problem was addressed in subsequent studies. In one study we asked if visual audience effects influence male mate choice decisions also in light-reared individuals of the cave form of P. mexicana.2 Cave mollies were particularly interesting to study because (a) they have maintained eyes as well as a response to visual cues27,28 and (b) cave mollies have genetically reduced aggressive behavior.29 This allowed us to ask if audience effects would occur also in a system were avoidance of aggressive encounters between the two males plays no role. When comparing the response of surface and cave dwelling P. mexicana males to an audience, the observed effect did not differ statistically between populations. This study suggested that male audience effects in poeciliids might be independent of the perceived risk of aggressive encounters (i.e., males do not just move away from the initially preferred female to avoid aggressive encounters with the rival).

Another line of argument in favor of the hypothesis that altering mate choice in the presence of rivals is adaptive for males comes from the observation of female mate choice.3 When we tested for an effect of a same-sex audience on the expression of females' mating preferences in P. mexicana (surface and cave form) and the related P. formosa, no effect of an audience female on female mate choice behavior was observed. If the split-attention hypothesis were true, then also females should have altered their mate choice behavior when an audience was presented, because focal females during the tests dedicated a considerable part of their time to the audience females.3

Males Deceive Rivals about Mating Preferences

In a recent study4 we examined a possible adaptive function of the described audience effect in P. mexicana males. In this study we used a full contact design, in which individual focal males could interact freely with a large and a small conspecific female, or a conspecific female and an equal-sized P. formosa. In both experiments, all males underwent an initial test to establish their baseline preferences and were randomly retested either with an audience male present, or—as a control—without an audience. Again, the audience males were presented in a clear Plexiglas cylinder, to avoid physical interactions. We measured nipping (a sexual behavior that typically precedes actual mating), gonopodial thrusts (i.e., attempts to insert the male copulatory organ into the female genital opening) and the first sexual interaction, which signifies the male's initial mating preference.

During the first part of experiment 1, males directed significantly more nipping and copulations towards the larger female, and conspecific females were preferred in experiment 2 (Fig. 4). When no audience male was presented during the second part of the tests (control), male preferences were highly consistent and essentially unchanged. The result was completely different when an audience male was present: males showed no longer a preference for larger females as measured as nipping and thrusting. In experiment 2, they even performed significantly more nipping with the heterospecific female (Fig. 4B). Overall, mating activity was reduced when an audience was presented.

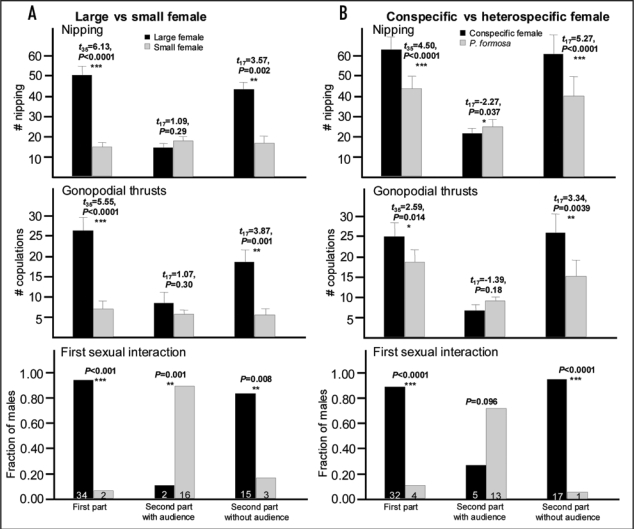

Figure 4.

Change of mating preferences in the presence of an audience in P. mexicana males. During the first part (left), the focal male could interact with two females without an audience (A: large and small, B: conspecific and P. formosa females). During the second part of the trials, half of the males were visually presented with an audience male (middle), while another half of the trials were repeated without an audience (right). The direction of male preferences was determined using paired t-tests. Note that that the direction of male preferences remained unchanged when no audience male was presented but was altered when an audience was visually presented. Below: the female with which the focal males first interacted (Binomial test). Given is the fraction of males first approaching either type of females (bars) and the numbers of males (inserted numbers). Note that most males first interacted with the initially non-preferred female when an audience was presented.4

During the first part of the experiments, most focal males first interacted with the large or conspecific female, respectively. Again, this preference remained unchanged when no audience male was presented during the second part. However, males first interacted significantly more often with the opposite, i.e., previously non-preferred female, when a competitor was present (Fig. 4, below). We argue that this behavior is used to deceive competitors about the focal male's preferred mate. This deception should work powerfully because molly males are known to copy other males' mate preferences and even switch to heterospecific females after an opportunity to copy.5

Providing information that directs the mate preferences of rivals away from the focal male's potential mate could reduce sperm competition, which is intense in poeciliids due to internal fertilization and sperm storage.30,31 Sending deceptive signals and leading competitors away from a preferred female may be a powerful alternate mating strategy providing relief from sperm competition in highly dynamic mating systems like that seen in poeciliid fishes. Deception appears to have evolved as a counter-strategy in a system with a high potential for male mate choice copying.

It will be important for future studies to test a central hypothesis derived from this study, namely, that deception indeed evolved as a counter-strategy in the face of male mate choice copying. We propose a comparative approach of testing for a correlation between the strength of male mate choice copying (for the experimental design see5 and deceptive behavior4 in various poeciliid species/populations. Based on our current data, we predict that deceptive behavior will occur only in species/populations with a high potential for male mate choice copying.

Future studies will also need to evaluate the potential for males to eavesdrop on other males' mate choice (mate copying) as well as the potential for males to show deceptive behavior in natural populations, because male mate choice copying cannot be evolutionarily stable if males always have an opportunity to deceive rivals.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Communicative & Integrative Biology E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cib/article/7199

References

- 1.Plath M, Blum D, Schlupp I, Tiedemann R. Audience effect alters mating preferences in Atlantic molly (Poecilia mexicana) males. Anim Behav. 2008;75:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plath M, Blum D, Tiedemann R, Schlupp I. A visual audience effect in a cavefish. Behaviour. 2008;145:931–947. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plath M, Kromuszczynski K, Tiedemann R. Audience effect alters male but not female mating preferences. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2008 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plath M, Richter S, Tiedemann R, Schlupp I. Male fish deceive competitors about mating preferences. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1138–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlupp I, Ryan MJ. Male sailfin mollies (Poecilia latipinna) copy the mate choice of other males. Behav Ecol. 1997;8:104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson M. Sexual Selection. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witte K, Ryan MJ. Mate choice copying in the sailfin molly, Poecilia latipinna, in the wild. Anim Behav. 2002;63:943–949. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witte K, Ueding K. Sailfin molly females (Poecilia latipinna) copy the rejection of a male. Behav Ecol. 2003;14:389–395. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valone TJ. From eavesdropping on performance to copying the behavior of others: a review of public information use. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2007;62:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westneat DF, Walters A, McCarthy TM, Hatch MI, Hein WK. Alternative mechanisms of nonindependent mate choice. Anim Behav. 2000;59:467–476. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGregor PK, Peake T. Communication networks: social environments for receiving and signaling behaviour. Acta Ethol. 2000;2:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earley RL, Dugatkin LA. Fighting, mating and networking: pillars of poeciliid sociality. In: McGregor PK, editor. Animal Communication Networks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 84–113. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matos R, Schlupp I. Performing in front of an audience—signalers and the social environment. In: McGregor PK, editor. Animal Communication Networks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira RF, Lopes M, Carneiro LA, Canário AVM. Watching fights raises fish hormone levels. Nature. 2001;409:475. doi: 10.1038/35054128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doutrelant C, McGregor PK. Eavesdropping and mate choice in female fighting fish. Behaviour. 2000;137:1655–1669. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mennill DJ, Boag PT, Ratcliffe LM. The reproductive choices of eavesdropping female black-capped chickadees, Poecile atricapillus. Naturwissenschaften. 2003;90:577–582. doi: 10.1007/s00114-003-0479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ophir A, Galef BG. Female Japanese quail that “eavesdrop” on fighting males prefer losers to winners. Anim Behav. 2003;66:399–407. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aquiloni L, Buric M, Gherardi F. Crayfish females eavesdrop on fighting males before choosing the dominant mate. Curr Biol. 2008;18:462–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marler P, Dufty A, Pickert R. Vocal communication in the domestic chicken II. Is a sender sensitive to the presence and nature of a receiver? Anim Behav. 1986;34:194–198. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuberbühler K. Audience effects. Curr Biol. 2008;18:189–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dugatkin LA. Sexual selection and imitation: females copy the mate choice of others. Am Nat. 1992;139:1384–1389. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matos R, Mc Gregor PK. The effect of the sex of an audience on male-male display of Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens) Behaviour. 2002;139:1211–1221. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marler CA, Ryan MJ. Origin and maintenance of a female mating preference. Evolution. 1997;51:1244–1248. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb03971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kokko H, Heubel K, Rankin DJ. How populations persist when asexuality requires sex: the spatial dynamics of coping with sperm parasites. Proc Roy Soc Lond B. 2008;275:817–825. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlupp I, Riesch R, Tobler M. Amazon mollies. Curr Biol. 2007;17:536–537. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlupp I, Rioux A, Heubel KU, Ryan MJ. A sexual preference modified by an audience effect. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plath M, Parzefall J, Körner KE, Schlupp I. Sexual selection in darkness? Female mating preferences in surface- and cave-dwelling Atlantic mollies, Poecilia mexicana (Poeciliidae, Teleostei) Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2004;55:596–601. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tobler M, Schlupp I, Plath M. Does divergence in female mate choice affect male size distributions in two cave fish populations? Biol Lett. 2008;4:452–454. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parzefall J. Rückbildung aggressiver Verhaltensweisen bei einer Höhlenform von Mollienesia sphenops (Pisces, Poeciliidae) Z Tierpsychol. 1974;35:66–84. (Ger). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans JP, Zane L, Francescato S, Pilastro A. Directional postcopulatory sexual selection revealed by artificial insemination. Nature. 2003;421:360–363. doi: 10.1038/nature01367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans JP, Pierotti M, Pilastro A. Male mating behavior and ejaculate expenditure under sperm competition risk in the eastern mosquitofish. Behav Ecol. 2003;14:268–273. [Google Scholar]