Abstract

The development of cell therapies to treat peripheral vascular disease has proven difficult because of the contribution of multiple cell types that coordinate revascularization. We characterized the vascular regenerative potential of transplanted human bone marrow (BM) cells purified by high aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDHhi) activity, a progenitor cell function conserved between several lineages. BM ALDHhi cells were enriched for myelo-erythroid progenitors that produced multipotent hematopoietic reconstitution after transplantation and contained nonhematopoietic precursors that established colonies in mesenchymal-stromal and endothelial culture conditions. The regenerative capacity of human ALDHhi cells was assessed by intravenous transplantation into immune-deficient mice with limb ischemia induced by femoral artery ligation/transection. Compared with recipients injected with unpurified nucleated cells containing the equivalent of 2- to 4-fold more ALDHhi cells, mice transplanted with purified ALDHhi cells showed augmented recovery of perfusion and increased blood vessel density in ischemic limbs. ALDHhi cells transiently recruited to ischemic regions but did not significantly integrate into ischemic tissue, suggesting that transient ALDHhi cell engraftment stimulated endogenous revascularization. Thus, human BM ALDHhi cells represent a progenitor-enriched population of several cell lineages that improves perfusion in ischemic limbs after transplantation. These clinically relevant cells may prove useful in the treatment of critical ischemia in humans.

Introduction

Regenerative angiogenesis is an area of intense preclinical study in relation to ischemic cardiomyopathy1–3 and peripheral vascular disease.4–6 Asahara et al first identified circulating endothelial precursors that differentiated into mature endothelial cells in vitro and contributed to vessel formation after transplantation.7 Subsequent studies revealed that these rare cells expressed the primitive stem cell markers CD34, CD133, and Flk-1/KDR, the human homolog for vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR2).8 These markers are also expressed on hematopoietic repopulating cells,9–11 making it difficult to distinguish progenitor cells with endothelial or hematopoietic function. Nonetheless, both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells can be transplanted to augment vascularization in mouse models.6,12,13

Recent studies have delineated the proangiogenic properties of human cells from hematopoietic and endothelial lineages.14,15 Adherent blood-derived cells propagated under strict endothelial cell (EC) growth conditions formed proliferative colonies composed of CD45− ECs with typical cobblestone appearance. These cells retained the ability to form perfused vessels in gel implants in vivo.15 In contrast, nonadherent blood-derived cells cultured under less restrictive conditions expressed both hematopoietic and EC markers and possessed myeloid progenitor cell activity in secondary cultures. After transplantation, these proangiogenic myelomonocytic cells did not incorporate into the vessel wall. Rather, this population promoted angiogenesis through proposed paracrine functions to increase sprouting of vessel-derived ECs.12,16 Mesenchymal stem cells may also participate in the support of myocardial17,18 and EC survival19 and have recently been shown to stabilize nascent blood vessels in vivo.20,21 Thus, human bone marrow (BM) provides an accessible reservoir of several lineages potentially involved in the vascularization of ischemic tissues.

Transplantation of a purified BM-derived population composed of several potentially proangiogenic cell lineages could provide a unique strategy to augment revascularization in ischemic tissues. Consequently, we purified human BM cells based on a conserved stem cell function, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity, an enzyme with high expression in primitive hematopoietic progenitors, and reduced expression in differentiated leukocytes.22 We have previously shown that human umbilical cord blood cells selected for high ALDH activity (ALDHhi) were enriched for hematopoietic repopulating cells23,24 and exhibited widespread distribution of nonhematopoietic (CD45−) cells after transplantation into the β-glucuronidase–deficient nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency/mucopolysaccharidosis type VII (NOD/SCID/MPSVII) mouse.25 Thus, nonhematopoietic cells with potentially proangiogenic functions may also possess high ALDH activity,26 whereas cultured mature ECs with enhanced proliferative and migratory activity were previously shown to be ALDH-low.27

Here we show that selection of human BM cells with high ALDH activity purifies a functionally heterogeneous group of hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic colony-forming cells based on a conserved progenitor cell function. ALDHhi mixed lineage cells possessed full multipotent hematopoietic and mesenchymal-stromal colony-forming cell capacity in vitro. After femoral artery ligation/transection in immunodeficient NOD/SCID β-2 microglobullin (β2M) null mice, intravenously transplanted human BM-derived ALDHhi cells showed recruitment to the site of ischemia and stimulated revascularization, resulting in improved limb perfusion.

Methods

Human cell purification

Human BM was obtained with informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki by aspirate of the iliac crest at the Siteman Cancer Center Oncology Clinic (St Louis, MO) or at the London Health Sciences Center (London, ON). Local research ethics committees at Washington University and the University of Western Ontario approved all studies. Unpurified nucleated leukocytes or mononuclear cells (MNCs) isolated by Ficoll-hypaque centrifugation were depleted of erythrocytes by red cell lysis and stained with Aldefluor reagent (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC), allowing the discrimination of fluorescence in cells with low or high ALDH activity and low side scatter by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) as previously described.23,24 Aldefluor-labeled nucleated cell samples were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove accumulated fluorescent substrate via reactivation of inhibited transporters. CD14+ monocytes were purified from granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilized peripheral blood using a RoboSep immunomagnetic cell separator and reagents (StemCell Technologies).

Progenitor assays

Human hematopoietic colony-forming cell (HCFC) assays were performed in Methocult H4434 (StemCell Technologies), as previously described,23 and enumerated by morphology after incubation for 14 to 17 days. Human mesenchymal colony-forming cell (MCFC) cultures were established by plastic adherence in Amniomax media plus supplement (Invitrogen Canada, Burlington, ON). Human endothelial colony-forming cell assays28 were performed on collagen-coated plates (BD BioCoat, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), in endothelial growth media (EGM-2 + Single Quots; Lonza Walkersville, Walkersville, MD). Nonhematopoietic CFCs were enumerated at days 10 to 14 using an inverted microscope.

Phenotype analysis

Purified human BM ALDHlo or ALDHhi cells and cultured cells were stained with antihuman antibodies for CD4, CD8 (T cells), CD14 (monocytes), CD19, CD20 (B cells), CD31 (PECAM-1), CD33 (myeloid cells), CD34 (sialomucin), CD73 (ecto-5′ nucleotidase), CD90 (Thy-1), CD105 (endoglin, GeneTex, San Antonio, TX), CD117 (c-kit), CD133 (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), and CD144 (VE-cadherin, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) All antibodies were from BD Biosciences unless otherwise indicated. Cell viability was assessed by 7-amino-actinomycin D (BD Biosciences). Cell surface marker expression was acquired using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Multipotent mesenchymal lineage differentiation

ALDHlo- and ALDHhi-derived MCFCs were differentiated in secondary cultures using adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic BulletKits, as described in the manufacturer's protocols (Lonza Walkersville). For adipocytes, lipid droplets were stained with Oil Red O (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). For osteocytes, mineral deposition was stained with Alizarin Red (Osteogenesis Quantication Kit; Millipore, Billerica, MA). For chondrocytes, cell pellets were stained with Safranin-O.

Tubule formation assays in Matrigel basement membrane matrix

Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) and BM ALDHhi cells, which established cell outgrowth under mesenchymal (Amniomax) and endothelial (EGM-2) growth conditions, were harvested for secondary culture at 50 000 to 75 000 cells/well in Matrigel basement membrane matrix (BD Biosciences). After 24 to 48 hours, tubule formation was examined using an inverted microscope.

Murine hindlimb ischemia surgery and laser Doppler perfusion imaging

Right femoral and saphenous artery ligation, followed by complete excision of the ligated femoral artery, was performed on anesthetized NOD/SCID β2M null or NOD/SCID/MPSVII mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) as previously described.16,29 Mice were tail vein-injected with PBS, human BM nucleated cells, purified ALDHlo, or ALDHhi cells, or CD14+ cells within 24 hours of surgery without preparative irradiation. Before laser Doppler perfusion imaging (LDPI; MoorLDI-2; Moor Instruments, Devon, United Kingdom), anesthetized mice were placed on a 37°C heating plate for 5 minutes to minimize body temperature variations. Mouse hindquarters were imaged before and after surgery and weekly for up to 28 days. Perfusion ratios (PRs) of ischemic versus nonischemic limbs were quantified by averaging relative units of flux from the ankle to the toe using MoorFlow Software (Moor Instruments, Axminster, United Kingdom).

Detection of human cells in BM, spleen, and muscle

At 21 to 30 days after transplantation, BM, spleen, and the adductor muscle from ischemic and nonischemic limbs were analyzed for human cell engraftment by flow cytometry for the human pan-leukocyte marker CD45 and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–A,B,C or matched isotype controls, combined with 7-amino-actinomycin D viability dye (BD Biosciences). BM and spleen cells were mechanically dispersed, and muscle was treated with type II collagenase (Worthington Biochemicals, Freehold, NJ). In mouse tissues with a low frequency of human cells (< 0.2% HLA-A, B, and C+), engraftment was confirmed by amplification of human-specific P17H8 satellite sequences by polymerase chain reaction as described previously.24

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Adductor muscle was embedded in optimum cutting temperature medium (Tissue Tek; Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), sectioned, and analyzed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) for human cells. Frozen sections were fixed in 10% buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich) and blocked with mouse-on-mouse reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Mouse anti–human HLA-A, B, and C diluted 1/500 was subsequently detected with alkaline phosphatase goat anti–mouse IgG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). For capillary density quantification, muscle sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and observed under light microscopy for capillary density per mm2. For each mouse, 10 fields were counted for capillaries in a blinded fashion. Mouse vascular structures were also visualized using a rabbit anti–human vWF polyclonal antibody cross-reactive to murine ECs.

AlexaFluor 750-nm–conjugated Feridex nanoparticle cell labeling

Synthesis of AlexaFluor 750–conjugated Feridex (Fe[750]) nanoparticles was based on previously published methods.30,31 Purified ALDHlo and ALDHhi cells were incubated with Fe[750] nanoparticles in fibronectin (CH-296 25 μg/cm2)–coated plates (Takara Shuzo, Otsu, Japan) as described,31 and cultured in serum free X-Vivo 15 media (Lonza Walkersville) supplemented with 10 ng/mL recombinant human thrombopoietin, recombinant human stem cell factor, and Flt-3 ligand (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Fe[750] nanoparticles were prepared with protamine sulfate (American Pharmaceuticals, Schaumberg, IL) and added to 2 × 105 cells/well at a concentration of 10 μg/mL. Cells were harvested after 18 hours using enzyme-free cell dissociation buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). BM ALDHlo cells did not efficiently uptake nanoparticles.

FACS purification, transplantation, and in vivo imaging of Fe[750]-labeled cells

Fe[750] nanoparticle-labeled cells were sorted using forward and orthogonal light scattering to exclude unbound Fe[750] nanoparticles and to segregate Fe[750]lo- and Fe[750]hi-labeled cells before transplantation. To verify nanoparticle intracellular localization, cells were cytospun and fixed and stained with Prussian blue and eosin. NOD/SCID β2M-null mice were transplanted within 24 hours of femoral artery ligation with PBS, Fe[750] nanoparticles, Fe[750]lo-, or Fe[750]hi-labeled cells. Fluorescence imaging was performed using a Kodak 4000MM multimodal imager (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) with an IS4000MM CCD camera. All images were normalized to an internal standard containing a known concentration of Fe[750]. X-ray and fluorescent images were overlaid and processed using Kodak image analysis software.

Human cell detection in transplanted NOD/SCID/MPSVII mice

We also transplanted β-glucuronidase (GUSB)–deficient NOD/SCID/MPSVII mice to track transplanted human cell recruitment to the ischemic tissue in situ.25,32 After femoral artery ligation and at 2 or 30 days after transplantation, human cells present in frozen ischemic muscle sections were detected by IHC for ubiquitous expression of GUSB in human cells and costained for CD45 expression as previously described.25

Hematopoietic reconstitution

BM-derived ALDHlo and ALDHhi cells were transplanted by tail vein injection into 8- to 10-week-old, sublethally irradiated (300 cGy) NOD/SCID or NOD/SCID β2M-null mice (Jackson Laboratory) as previously described.23 Seven to 8 weeks after transplantation, BM and spleen were analyzed for human hematopoietic chimerism by flow cytometry for human CD45 and human HLA A,B,C (BD Biosciences). Analysis of multilineage engraftment was performed for B-lymphoid cells (CD19, CD20), myeloid cells (CD33, CD14), T-lymphoid cells (CD8, CD4), and primitive progenitor cells (CD34, CD133) (all antibodies from BD except for anti–CD133-PE from Miltenyi Biotec) as previously described.23

Statistics

Data are mean plus or minus SEM. Analyses of statistical significance were performed by Student t test.

Results

BM-derived ALDHhi cells express progenitor and monomyelocytic markers

To prospectively purify human BM cells based on a conserved progenitor cell function,23,24,33 we FACS-purified human BM nucleated cells based on low side scatter properties and low (8.2% ± 1.3% of nucleated cells) versus high (0.8% ± 0.2% of nucleated cells) ALDH activity (n = 11, Figure 1A). Scatter profiles for each purified population revealed that ALDHhi cells were larger than ALDHlo cells (*P < .01), indicated by increased forward scatter mean fluorescence intensity (Figure 1B,C). Although this stringent sorting strategy removed granulocytes with high side scatter, BM samples were not depleted for lineage-committed cells before sorting. This allowed subsequent characterization of cell surface phenotype on ALDHlo and ALDHhi cells without the removal of mature hematopoietic cells with potential proangiogenic functions.12

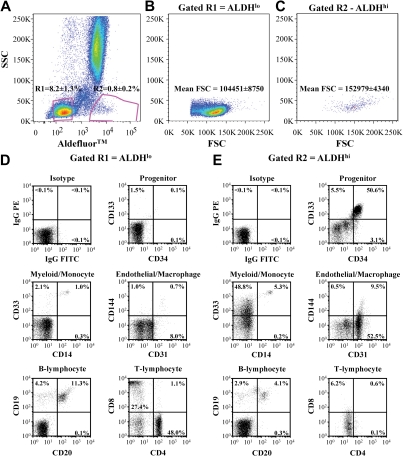

Figure 1.

Purification and cell surface marker expression of ALDHlo and ALDHhi cells isolated from human BM. (A) Human BM cells were selected for low side scatter and low (R2 = 8.2% ± 1.3%) or high (R3 = 0.8% ± 0.2%) Aldefluor fluorescence (n = 11). (B,C) ALDHhi cells showed increased forward scatter mean fluorescence intensity compared with ALDHlo cells. (D,E) Representative FACS of ALDHlo and ALDHhi cells for human cell surface markers expressed on primitive progenitors (CD34, CD133), monomylocytic cells (CD14, CD33), ECs (CD31, CD144), B lymphocytes (CD20, CD19), and T lymphocytes (CD4, CD8).

ALDHlo cells highly expressed the pan-leukocyte marker CD45 (98.5% ± 1.4%) and were significantly enriched for T lymphocytes (CD4, CD8) and B lymphocytes (CD19, CD20; Figure 1D,E; Table 1). In contrast, ALDHhi cells demonstrated lowered CD45 expression (85.9% ± 5.6%, Table 1), suggesting increased representation of nonhematopoietic cells. BM ALDHhi cells also showed increased coexpression of primitive cell surface markers, CD34, CD117 (c-kit), and CD133 (Figure 1D,E; Table 1), confirming that known progenitor phenotypes from human BM possess high ALDH activity.23,24 Approximately half of the ALDHhi cells expressed the early myeloid marker CD33 with a distinct cluster of CD33+CD14+ cells (Figure 1E), suggesting that the ALDHhi population also contained myeloid progenitors and monocytes. In contrast, the ALDHlo population showed reduced CD33+ myeloid cells and CD14 coexpressing monocytes (Table 1). The ALDHhi purified population highly expressed CD31 (PECAM-1), an adhesion molecule expressed on ECs, platelets, monocytes, and macrophages, yet few cells coexpressed CD144 (VE-cadherin), an EC-restricted marker. Collectively, these analyses suggested that the ALDHhi population was composed of cells previously associated with both endothelial and hematopoietic progenitor function and also contained myelomonocytic cells implicated in the support of blood vessel formation.4,12,15,34

Table 1.

Cell surface marker expression of human BM-derived ALDHlo and ALDHhi cells

| Cell type | Hematopoietic |

Progenitor |

Endothelial |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD45 (%) | CD3 (%) | CD19 (%) | CD14 (%) | CD34 (%) | CD133 (%) | CD117 (%) | CD144 (%) | |

| ALDHlo | 98.5 ± 1.4* | 75.3 ± 5.3† | 15.4 ± 2.3* | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 1.4 | 2.6 ± 0.4 |

| ALDHhi | 88.9 ± 5.8 | 6.2 ± 2.5 | 4.4 ± 2.1 | 12.0 ± 3.5* | 50.2 ± 1.8† | 51.7 ± 7.6† | 74.9 ± 7.5† | 8.9 ± 2.4* |

BM-derived ALDHlo cells showed increased expression of hematopoietic (CD45), and T- (CD3) and B-lymphocyte (CD19) markers. BM-derived ALDHhi cells showed increased expression of primitive progenitor (CD34, CD133, CD117), monocytic (CD14), and endothelial cell (CD144) markers. All cell-surface markers were assessed by FACS, n = 4-6.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Transplantation of human BM-derived ALDHhi cells augments perfusion and capillary density in ischemic limbs

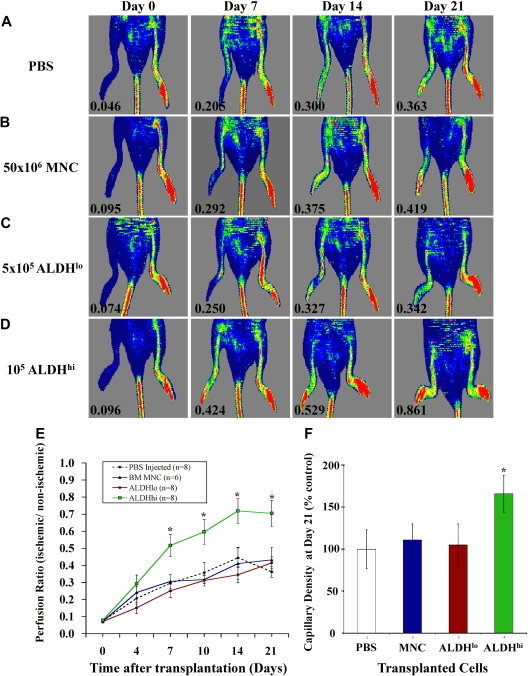

We induced unilateral ischemia in the right hindlimb of immune-deficient NOD/SCID β2M null mice by transection of the femoral artery and ligation of collateral vessels. Blood flow quantified by PR between the ischemic and nonischemic limbs was reduced more than 10-fold by LDPI to a mean PR of 0.08 (± 0.02) for all surgically treated mice, confirming the induction of severe limb ischemia (Figure 2). Representative LDPI are shown weekly to document the recovery of perfusion for 21 days after injection of PBS (Figure 2A), unpurified BM nucleated cells (Figure 2B), ALDHlo cells (Figure 2C), or ALDHhi cells (Figure 2D). PBS-injected mice showed endogenous recovery of perfusion from 0.07 plus or minus 0.02 after surgery to a plateau of 0.34 (± 0.07) at day 21 (Figure 2E). This baseline recovery was sufficient to prevent untoward morbidity or limb loss in experimental animals. Recovery of limb perfusion was similar to PBS-injected controls after tail vein injection of 50 × 106 BM nucleated cells (equivalent of 4 × 105 ALDHhi cells at 0.8% frequency, Figure 1) or 5 × 105 BM-derived ALDHlo cells (Figure 2E). In contrast, injection of 1 to 2 × 105 ALDHhi cells significantly augmented blood flow by 7 days after transplantation (PR = 0.50 ± 0.08) compared with injection of PBS (PR = 0.29 ± 0.05) or transfer of nucleated cells (PR = 0.30 ± 0.04) or ALDHlo cells (PR = 0.25 ± 0.05). ALDHhi cell-transplanted mice continued to improve perfusion up to day 21 (PR = 0.71 ± 0.08; Figure 2D,E), doubling the extent of blood flow recovery in the PBS-injected cohort (PR = 0.34 ± 0.07; Figure 2E). Mice injected with ALDHhi cells also exhibited increased capillary density in the ischemic limb (Figure 2F). Compared with robust blood vessel detection in the nonischemic limb (Figure S1A, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), the ischemic limbs of mice transplanted with PBS or ALDHlo cells (Figure S1B,C) showed reduced blood vessel density, marked by fewer vWF+ ECs (brown). In contrast, mice transplanted with BM ALDHhi cells showed an increased frequency of vWF+ ECs forming contiguous vascular structures between muscle fibers in ischemic tissue (Figure S1D). These data confirm that improvement in perfusion in mice transplanted with ALDHhi cells was the result of revascularization of ischemic limbs.

Figure 2.

Transplantation of BM-derived ALDHhi cells improved perfusion and capillary density in ischemic limbs. (A-D) Representative LDPI after right femoral artery ligation and tail vein injection of PBS (n = 8), 50 × 106 BM MNCs (n = 6), 5 × 105 ALDHlo (n = 8), or 1 to 2 × 105 ALDHhi cells (n = 8) monitored weekly for 21 days. Numbers in the lower left of each LDPI image indicate PR of the ischemic versus the nonischemic limb. (E) Summary of PRs for all mice transplanted as indicated in panels A through D. Transplantation of BM ALDHhi cells augmented perfusion in ischemic limbs from 7 to 21 days after transplantation (*P < .05). (F) Capillary density at days 21 to 28 was increased in mice transplanted with ALDHhi cells (*P < .05). All micrographs were viewed with an Olympus (Hamburg, Germany) BX50 microcoscope using air lenses and betaglucuronidase and hematoxylin stains. All images were taken with a Hitachi HV-F2S CCD camera using Northern Eclipse version 7.0 software. The following numeric aperture (NA) air objectives were used: panels C and F, 10×/0.30; panels E and G, 20×/0.50.

Because the human ALDHhi population contained a significant number of myelomonocytic cells (∼ 12% CD14+) previously implicated in angiogenesis,34,35 we investigated whether CD14-selected human monocytes could similarly induce recovery of perfusion. Transplantation of 1 to 4.5 × 106 CD14+ monocytes from mobilized peripheral blood did not augment perfusion in the ischemic limb (PR = 0.42 ± 0.13 at day 28) compared with baseline recovery observed in PBS-injected controls (PR = 0.41 ± 0.06, Figure S2) and further underscore the robust blood flow recovery observed after the transplantation of BM ALDHhi cells.

Efficient recruitment of human BM ALDHhi cells to the ischemic limb

Because hypoxia is a strong stimulus for the recruitment of circulating cells to ischemic tissue,32 we labeled human ALDHhi cells with fluorescent Fe[750] nanoparticles and tracked cell recruitment to the ischemic limb after transplantation.31 Excess unbound Fe[750] nanoparticles were removed from Fe-labeled cells by extensive washes in PBS and by the selection of the cells based on forward and side scatter properties (R1, Figure 3A) during FACS of ALDHhi cells with low (Fe[750]lo) and high (Fe[750]hi) fluorescence (Figure 3B). ALDHhi cells loaded iron nanoparticles with variable efficiency. A total of 22.5% (± 6.5%) of cells (ALDHhiFe[750]hi cells) were highly loaded with iron, whereas 47.3% plus or minus 9.9% of cells demonstrated decreased iron labeling (ALDHhiFe[750]lo cells; Figure 3B). Our previous studies have shown that potentially phagocytic myeloid progenitors and monocytes label efficiently in vitro.31 An aliquot of purified ALDHhiFe[750]hi cells was used to localize iron nanoparticles within the cytoplasm of intact cells by Prussian blue staining (Figure 3C). Trypan blue viability after FACS purification was more than 90% (n = 3), suggesting that cell death was not increased by cell culture, iron loading, or subsequent flow-based sorting.

Figure 3.

Transplanted BM-derived ALDHhi cells are recruited to the ischemic limb. (A,B) Representative FACS showing removal of noncellular events (R1) and selection of ALDHhiFe[750]lo (R2 = 47.3% ± 9.9%) and ALDHhiFe[750]hi (R3 = 22.5% ± 6.5%) nanoparticle-labeled cells (n = 5). (C) Prussian blue staining of sorted ALDHhiFe[750]hi cells shows cytoplasmic accumulation of iron nanoparticles. (D) Recruitment of ALDHhiFe[750]hi cells to the site of ischemic injury 24 to 48 hours after transplantation demonstrated by Kodak multimodal imaging. Intense signal beside mouse limb represents internal standard for Fe[750] fluorescence. (E) Two days after MNC injection, CD45+ cells (brown) were detected near arterioles ( , inset), and GUSB+ human cells (red) that were negative for CD45 expression were detected adjacent to muscle fibers (

, inset), and GUSB+ human cells (red) that were negative for CD45 expression were detected adjacent to muscle fibers ( ) in the ischemic limb. (F) Human cells were not detected in the ischemic limbs of mice transplanted with BM ALDHlo cells. (G) After injection of ALDHhi cells, GUSB+CD45− human cells were detected adjacent to vascular structures and muscle fibers as early as 2 days after transplantation and remained for up to 30 days after transplantation (

) in the ischemic limb. (F) Human cells were not detected in the ischemic limbs of mice transplanted with BM ALDHlo cells. (G) After injection of ALDHhi cells, GUSB+CD45− human cells were detected adjacent to vascular structures and muscle fibers as early as 2 days after transplantation and remained for up to 30 days after transplantation ( ). (H,I) Transplantation of ALDHhiFe[750]hi cells produced increased fluorescence in the ischemic limb at 1 and 7 days. Fluorescent signal was cleared from the ischemic limb by 14 days after transplantation (n = 3).

). (H,I) Transplantation of ALDHhiFe[750]hi cells produced increased fluorescence in the ischemic limb at 1 and 7 days. Fluorescent signal was cleared from the ischemic limb by 14 days after transplantation (n = 3).

Purified ALDHhiFe[750]hi cells were transplanted into the tail vein of immune-deficient mice with acute limb ischemia. After injection of a high dose of nanoparticle-loaded cells (106 ALDHhiFe[750]hi cells), fluorescent signal was detected at the site of surgically induced ischemia as early as 24 hours after transplantation (Figure 3D), whereas fluorescent signal was not observed in the nonischemic limb (Figure 3D). Injection of unlabeled cells or free nanoparticles did not produce fluorescent signal in the ischemic limb (data not shown). At 48 hours after transplantation, fluorescent signal continued to accumulate in the ischemic region and dispersed throughout the ischemic muscle but did not penetrate significantly into the ankle or foot further downstream of the damage site (Figure 3D).

We also used NOD/SCID/MPSVII (GUSB-deficient) mice to track transplanted cells to the ischemic tissue based on ubiquitous GUSB activity (red) in human cells and costained for human CD45 (brown) expression.24 At 2 days after transplantation with 20 × 106 BM nucleated cells, human CD45+ hematopoietic cells were consistently detected adjacent to larger blood vessels in the ischemic limb (Figure 3E inset), and GUSB+ human cells that did not express CD45 were observed adjacent to muscle bundles (Figure 3E arrows). In contrast, human cells were not detected in ischemic muscles of mice 2 days after injection with up to 2 × 106 ALDHlo cells (Figure 3F). After injection of only 2 × 105 ALDHhi cells, GUSB+CD45− human cells were detected adjacent to vascular structures and muscle fibers as early as 2 days after transplantation and remained for up to 30 days (Figure 3G arrows).

Human ALDHhi cells transiently engraft the ischemic limbs of transplanted mice

Mice injected with 4 × 105 ALDHhiFe[750]lo (Figure 3H) or ALDHhiFe[750]hi cells (Figure 3I) showed increased fluorescence in the ischemic limb between 24 hours and 7 days after transplantation. However, between 7 and 14 days, the fluorescent signal rapidly declined, suggesting transient retention of recruited cells at the area of ischemia (Figure 3I). To confirm the transient engraftment of BM ALDHhi cells, murine BM, spleen, and adductor muscle from ischemic and nonischemic limbs were collected for analysis of human cell engraftment at 21 to 28 days after transplantation. Because recipient mice were not sublethally irradiated before transplantation, permanent human hematopoietic chimerism was not established in the BM or spleen of any transplanted mice. Few human cells (< 0.2% human HLA-A, B, C+ by FACS) were detected in the ischemic limb adductor muscle in 5 of 8 mice transplanted with human BM-derived ALDHhi cells. Low-level engraftment was confirmed by IHC for human HLA-A, B, C and by sensitive detection of human P17H8 sequences by polymerase chain reaction (data not shown). However, the persistence of human cells in the ischemic limb was rare (Figure 3G). Human cells were not detected in the ischemic limb of mice transplanted with human ALDHlo cells, and human cells were never detected in the nonischemic limb of any transplanted mice. Therefore, long-term hematopoietic chimerism and widespread retention of ALDHhi cells in the ischemic limb were not required for improved perfusion.

Human BM ALDHhi cells are enriched for HCFC and demonstrate repopulating function

BM-derived CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells and their differentiated progeny have been implicated in regenerative angiogenesis.6,12,16,35 Thus, ALDHlo and ALDHhi cells were plated in HCFC assays. Similar to ALDHhi cells from UCB,23 human BM-derived ALDHhi cells established colonies of erythroid, granulocyte, and macrophage lineages (Figure S3A). The frequency of HCFCs within the ALDHhi population (1 HCFC in 8 ALDHhi cells) was significantly increased compared with the corresponding ALDHlo cells (1 HCFC in 2325 ALDHlo cells, Figure 4A) and represented more than 70-fold enrichment for hematopoietic progenitors compared with BM MNCs (1 HCFC in 588 MNCs).

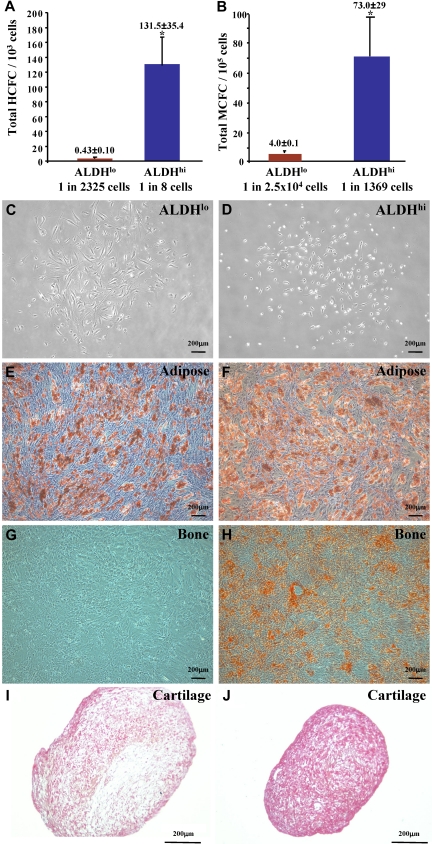

Figure 4.

Human BM ALDHhi cells are enriched for multipotent HCFCs and MCFCs. (A) ALDHhi cells cultured in methylcellulose media established hematopoietic colonies (1 HCFC in 8 cells) at an increased frequency compared with ALDHlo cells (1 HCFC in 2500 cells; *P < .05, n = 6). (B) ALDHhi cells cultured in Amniomax media established mesenchymal colonies (1 MCFC in 1370 cells) at an increased frequency compared with ALDHlo cells (1 MCFC in 2.5 × 104 cells; *P < .05, n = 5). ALDHlo- and ALDHhi-derived MCFCs (C,D) were differentiated into adipocytes (E,F), osteocytes (G,H), or chondrocytes (I,J). ALDHhi-derived MCFCs demonstrated multilineage differentiation forming adipocytes (Oil Red O+), osteocytes (Alizarin Red+), and chondrocytes (Safranin O+) in secondary cultures. ALDHlo-derived MCFCs showed reduced differentiative capacity (n = 3).

To quantify hematopoietic repopulating function in vivo, we transplanted sublethally irradiated (350 cGy) NOD/SCID (closed symbols) mice and NOD/SCID B2M null mice (open symbols) with purified ALDHlo (red) or ALDHhi (blue) cells and measured human cell chimerism in the BM of transplanted mice 7 to 8 weeks after transplantation (Figure S3B). As indicated, mice transplanted with 104 to 4 × 105 BM ALDHhi cells demonstrated hematopoietic reconstitution at frequencies ranging from 0.1% to 68.4% HLA-A, B, C+/CD45+ cells. In contrast, only 1 of 10 mice transplanted with ALDHlo cells showed surviving human cells in mouse BM. Engrafted human BM ALDHhi cells were capable of differentiation into mature myeloid and B-lymphoid cells (Figure S3C). Thus, similar to ALDH-selected UCB cells,23 the ALDHhi fraction of human BM was enriched for hematopoietic progenitors with multilineage repopulating function.

BM-derived ALDHhi cells are enriched for multipotent MCFC

Human BM also contains nonhematopoietic, multipotent mesenchymal-stromal cells (MSCs) capable of producing differentiated bone, cartilage, and adipose cells in vitro.36 Human MSCs have recently been implicated in the stabilization of functional neovessels in vivo.20 Both ALDHlo (Figure 4C) and ALDHhi (Figure 4D) cells from human BM resulted in the formation of plastic-adherent MCFCs with typical stromal-fibroblast morphology. As observed for HCFCs, MCFCs were enriched in the ALDHhi population (1 MCFC in 1369 ALDHhi cells) compared with the ALDHlo population (1 MCFC in 2.5 × 104 ALDHlo cells, Figure 4B). ALDHhi purification conferred more than 90-fold enrichment for MCFCs compared with unfractionated BM cells (1 MCFC in 1.3 × 105 MNCs, n = 4). Both ALDHlo and ALDHhi MCFCs established the outgrowth of stromal cells that expressed typical fibroblast cell surface markers CD73, CD90 (Figure S4A,B), and CD105 and were devoid of contaminating hematopoietic cells and ECs (Figure S4, Table 2). The primitive cell markers CD34 and CD133 were not expressed on cultured ALDHlo or ALDHhi MCFCs (Table 2). In secondary differentiation cultures, only the ALDHhi-derived MCFCs were truly multipotent and resulted in the production of Oil Red O-stained adipocytes (Figure 4F), Alizarin Red–stained osteocytes (Figure 4H), and Safranin O-stained chondrocytes (Figure 4J). ALDHlo-derived MCFC demonstrated reduced differentiation to bone and cartilage (Figure 4G,I). Thus, BM-derived ALDHhi cells are enriched for MCFC that meet the minimal criteria defining multipotent MSCs,37 whereas ALDHlo cells contained some MCFCs that showed restricted differentiation potential.

Table 2.

Cell-surface marker expression by human BM ALDHlo- and ALDHhi-derived CFC in Amniomax or complete EGM-2 media

| Cell type | Hematopoietic |

Progenitor |

Endothelial |

Endothelial/mesenchymal |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD45 (%) | CD14 (%) | CD34 (%) | CD133 (%) | CD31 (%) | CD144 (%) | CD105 (%) | CD73 (%) | CD90 (%) | |

| ALDHlo MCFC | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 98.4 ± 0.9 | 99.5 ± 0.4 | 97.8 ± 1.8 |

| ALDHhi MCFC | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 98.6 ± 0.8 | 99.8 ± 0.1 | 98.3 ± 0.5 |

| ALDHhi in EGM-2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.2† | 0.9 ± 0.6† | 81.7 ± 4.6 | 99.9 ± 0.1 | 38.5 ± 9.3* |

| HAEC in EGM-2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 5.8 ± 4.6 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 98.9 ± 1.0 | 50.0 ± 6.2 | 99.4 ± 0.2 | 99.0 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

Human BM ALDHlo- and ALDHhi-derived cells established plastic adherent colonies in Amniomax media, composed of stromal fibroblast cells that expressed CD105, CD73, and CD90. ALDHhi cells established proliferative nonhematopoietic colonies in EGM-2 media, and were composed of cells that did not express the EC markers CD31 or CD144, and demonstrated intermediate expression of the stromal fibroblast marker CD90. All cell-surface markers were assessed by FACS.

P < .05 compared with HAEC, n = 3-4.

P < .01 compared with HAEC, n = 3-4.

BM-derived ALDHhi cells form nonhematopoietic cell colonies under endothelial growth conditions that showed mesenchymal-stromal but not endothelial cell phenotypes

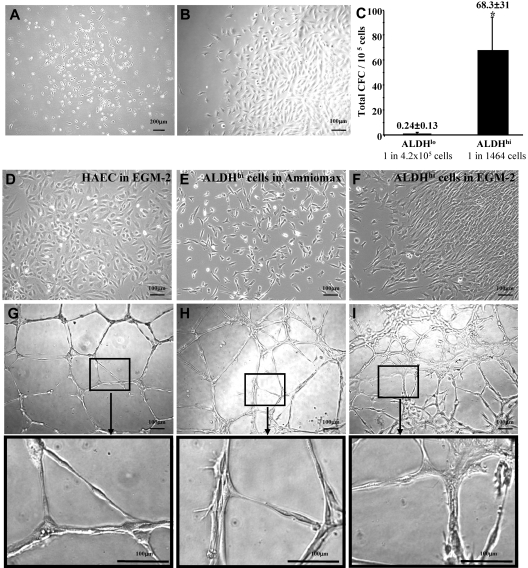

Because human BM contains endothelial progenitors that participate in revascularization,5,7,38 we assessed BM-derived ALDHlo and ALDHhi cells for colony formation in EGM-2 media supplemented with EC growth factors. Blood-derived ECFCs selected by these growth conditions have been previously shown to acquire EC markers and possess vessel-forming capacity after culture.15 BM-derived ALDHhi cells established circumscribed colonies between 9 and 14 days of culture (Figure 5A) with variable expansion kinetics. Three of 7 human BM samples established cellular outgrowth (Figure 5B), whereas other samples failed to propagate, resulting from acquisition of an extended morphology and subsequent growth arrest. The frequency of colony formation in EGM-2 media was significantly increased in ALDHhi cells (1 CFC in 1463 cells) compared with ALDHlo cells (1 CFC in 4.2 × 105 cells, n = 4, Figure 5C). EGM-2 culture did not support significant colony expansion by ALDHlo cells.

Figure 5.

Human BM ALDHhi cells cultured in mesenchymal- or endothelial-supportive conditions form cellular networks in secondary Matrigel cultures. (A) Human BM ALDHlo and ALDHhi cells cultured in complete EGM-2 media formed colonies at 9 to 14 days of culture. (B) Only ALDHhi colonies established proliferative outgrowth. (C) ALDHhi cells showed an increased frequency of colony formation (1 CFC in 1464 cells) compared with ALDHlo cells (1 CFC in 4.2 × 105 cells; *P < .05, n = 4). (D-F) HAECs cultured in EGM-2 media, ALDHhi cells cultured in Amniomax media, and ALDHhi cells cultured in EGM-2 were tested for spontaneous tubule forming capacity in secondary Matrigel assays. (G) Mature HAECs formed patterned multinucleated tubule networks. (H) ALDHhi MCFCs grown in Amniomax aggregated into organized cellular networks with elongated tubule-like cellular morphology. (I) ALDHhi cells grown in EGM-2 media also aggregated into cellular networks forming tubule-like structures with more diffuse cellular connections (n = 3).

Because these culture conditions support the growth of nonendothelial cell types, ALDHhi colonies expanded in EGM-2 media were harvested at day 28 for cell surface phenotypic analysis. These cells did not express monocyte (CD45, CD14) or primitive progenitor (CD34, CD133) markers (Table 2; Figure S4C), suggesting that these conditions did not support the growth of hematopoietic cells. However, in contrast to mature HAECs, ALDHhi cells did not acquire expression of the mature EC markers CD31 (PECAM-1) or CD144 (VE-cadherin) (Table 2; Figure S4C,D). ALDHhi cells grown in EGM-2 consistently expressed CD73 and CD105, markers with shared expression on both HAECs and MSCs.15,37 In contrast to HAECs, ALDHhi cells grown in EGM-2 also showed consistent expression of the marrow stromal marker CD90 (Table 2). Thus, ALDHhi cells from human BM established nonhematopoietic colonies in EGM-2 media, but subsequent cellular outgrowth showed typical stromal cell phenotypes rather than EC surface marker expression.

To further assess vessel-forming function of ALDHhi cells in vitro, HAECs (Figure 5D), were compared with ALDHhi cells propagated in Amniomax (Figure 5E) or EGM-2 (Figure 5F), for the ability to form closed capillary tubule networks in Matrigel assays (Figure 5G-I). At 24 hours, HAECs formed patterned multinucleated closed tubule networks (Figure 5G). By comparison, ALDHhi MCFCs grown in Amniomax aggregated into less structured tubule-like networks (Figure 5H). ALDHhi cells grown in EGM-2 also formed less organized networks characterized by elongated cellular connections (Figure 5I). These analyses suggest that high ALDH activity enriches for nonhematopoietic cells that survive in endothelial-specific conditions. However, resultant cellular outgrowth did not acquire typical EC phenotypes or function and underscores that propagation in EGM-2 does not confer endothelial progenitor cell function in vitro.

Discussion

Using a clinically relevant, FACS-based purification procedure based on high ALDH enzyme activity, we have prospectively isolated a heterogeneous cell population from adult human BM that improved functional perfusion after transplantation into mice with critical limb ischemia. The highly purified ALDHhi cells, representing less than 1% of total BM, were efficiently recruited to the ischemic limb after transplantation. However, these transplanted cells did not permanently integrate into the ischemic tissue, suggesting that low frequency or transient ALDHhi cell recruitment was sufficient to increase blood vessel density and improve limb perfusion.

The prospective isolation of rare BM-derived nonhematopoietic progenitor cell types has proven difficult using cell surface marker-based selection. The ALDHhi population contained cells with increased expression of known progenitor cell surface markers (CD34, CD133, CD117), was enriched for hematopoietic CFC with NOD/SCID repopulating capacity, and also contained differentiated myelomonocytic cells previously associated with proangiogenic properties.4,12,15,34 In addition, the ALDHhi population contained multipotent MSCs and nonhematopoietic cells that established colonies in endothelial growth media. These data are supported by a recent report,26 in which Gentry et al described EGM-2-cultured ALDHhi cells labeled efficiently with acetylated low density lipoprotein and possessed tubule formation capacity in growth factor reduced Matrigel matrix. Despite subtle differences in the culture methodologies used, human BM-derived ALDHhi cells cultured under both mesenchymal and endothelial supportive conditions had some ability to spontaneously form tube-like cellular networks, but these cells never acquired the full complement of EC surface markers in vitro. Therefore, high ALDH activity is a characteristic of a progenitor-enriched population of several lineages that, when transplanted as a heterogeneous population, allowed for the potential interaction of both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cell types with the damaged vascular endothelium. Although the specific contribution of each of these cell types during vascular recovery in vivo requires further experimentation, inclusive transplantation of these potentially regenerative cell types may further promote the recovery of functional perfusion.

A conserved function of potentially regenerative cell types is the ability to migrate selectively to ischemic or damaged tissues in response to hypoxia-inducible factor-1α-dependent up-regulation of stromal derived factor-1.32,39–41 Here we showed that tail vein injection of Feridex-labeled ALDHhi cells resulted in recruitment of ALDHhi cells to the area of ischemia within 24 hours, continued accumulation of labeled-ALDHhi cells for up to 7 days, and clearance of signal fluorescence from the ischemic limb 7 to 14 days after transplantation. Fluorescent nanoparticle redistribution may occur by several possible mechanisms, including active nanoparticle efflux and clearance, cell migration from the site of ischemia, or cell deletion and removal of released nanoparticles. Nonetheless, permanent integration of human cells in the ischemic muscle beyond 14 days after transplantation was rare. Although transient cell retention in the ischemic region cannot be attributed specifically to progenitor cells, recruitment of human BM purified ALDHhi cells resulted in functional and stable recovery of limb perfusion, consistent with the concept of cell-mediated tissue repair.42

The specific phenotypes and lineage restriction of transplanted BM-derived ALDHhi cells that initially recruit to areas of ischemia and the mechanisms by which these cells impact revascularization remain areas of active investigation. In contrast to the ALDHhi population, Schatteman et al documented that purified human BM CD34+ cells injected into nondiabetic murine recipients with limb ischemia did not accelerate the restoration of blood flow compared with vehicle control.4 Similarly, transplantation of ALDHlo cells, unsorted BM nucleated cells (containing the equivalent of 4-fold greater numbers of ALDHhi cells), did not augment perfusion. Although transplanted mobilized peripheral blood CD14-selected monocytes did not augment perfusion in our system, we cannot rule out the possibility that agranular myeloid cells or monocytes within the BM ALDHhi population may be implicated in revascularization. In addition, our data suggest a potential role for nonhematopoietic ALDHhi cells in the recovery of vascular function. Recently, several groups have identified a role for MSCs providing structural support to neovessels in vivo.20,21 We observed the recruitment of CD45− human cells adjacent to muscle fibers in the ischemic limb, suggesting that nonhematopoietic cells enriched within the ALDHhi population may potentially provide support to regenerating vasculature. Selective administration of lineage-restricted cell populations will be required to elucidate the putative functions of various cell types that coordinate specific aspects of neovessel formation.

BM-derived stem and progenitor cells repair tissues either by the direct replacement of damaged cells or by the induction of regeneration of tissue resident cells.42 Direct intramuscular injection of undifferentiated multipotent adult progenitor cells have recently been reported to restore blood flow and stimulate muscle regeneration in mice with limb ischemia via permanent cell replacement and trophic effects.43 Here, we describe that transplanted human BM ALDHhi cells also improve durable perfusion without permanent incorporation into limb vasculature. We propose that, after systemic infusion of BM ALDHhi cells and transient homing to the ischemic region, transplanted cells trigger collateral vessel formation or stabilization, resulting in improved perfusion. Although the cellular interactions or paracrine factors that mediate vascular regeneration are not fully elucidated at present, discovery of key molecules that mediate different aspects of neovessel formation may allow the development of drug therapies to more effectively treat ischemic diseases in the future.44,45

Functional characterization of both vascular cells and supportive cell lineages and quantification of their respective vascular regenerative functions using preclinical models are essential for the development of improved cellular therapies for vascular diseases. Recent clinical trials using the transfer of heterogeneous BM MNCs for limb ischemia46or cardiac repair47–49 have demonstrated variable efficacy with regard to new vessel formation, prompting investigators to search for specific cellular constituents for the generation of functional vasculature in vivo.50 We have identified a globally available and clinically relevant source of cells that may be administered to safely augment vascular recovery in ischemic limbs. Although our studies were performed in a model of acute ischemia, neither preparative irradiation nor permanent human hematopoietic chimerism was required to improve perfusion, suggesting that the delivery of autologous or allogeneic cells using minimal pretransplantation conditioning may be possible. Further clinical studies are required to determine the efficacy of these approaches for the treatment of critical limb ischemia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nica Borradaile for critical review of the manuscript, William Eades at the Washington University Flow Cytometry Core Facility, Kristin Chadwick at the London Regional Flow Cytometry Facility for cell sorting, and Heather Broughton for animal care, surgery, and LDPI.

This work was supported by Aldagen Inc (Durham, NC; D.A.H.), the Krembil Foundation (Toronto, ON; D.A.H.), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Ottawa, ON; MOP 86759, D.A.H.), and the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD; P50 CA94056, D.P.-W.; RO1 HL073256, J.A.N.; 2RO1DK61848, J.A.N.; and R01HL073762, D.C.L., J.A.N.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: B.J.C. performed femoral artery ligation and LDPI and collected and analyzed data; D.L.R. performed in vitro assays and IHC; K.D.L. performed in vitro culture and collected and analyzed data; D.J.M. performed nanoparticle labeling and imaging; M.J.N. and G.I.B. performed in vitro assays; A.X. provided human bone marrow samples; D.P.-W. provided imaging technology; D.C.L. and J.A.N. helped to analyze data and edited the manuscript; and D.A.H. designed and performed research, collected and analyzed data, supervised project, provided research funding, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: This work was supported by an operating grant from Aldagen Inc. The authors declare no other competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David A. Hess, Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Western Ontario, PO Box 5015, 100 Perth Dr, Room E4-19, London, ON, Canada, N6A 5K8; e-mail: dhess@robarts.ca.

References

- 1.Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM, Schneider MD. Unchain my heart: the scientific foundations of cardiac repair. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:572–583. doi: 10.1172/JCI24283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fazel S, Cimini M, Chen L, et al. Cardioprotective c-kit+ cells are from the bone marrow and regulate the myocardial balance of angiogenic cytokines. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1865–1877. doi: 10.1172/JCI27019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kocher AA, Schuster MD, Szabolcs MJ, et al. Neovascularization of ischemic myocardium by human bone-marrow-derived angioblasts prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis, reduces remodeling and improves cardiac function. Nat Med. 2001;7:430–436. doi: 10.1038/86498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schatteman GC, Hanlon HD, Jiao C, Dodds SG, Christy BA. Blood-derived angioblasts accelerate blood-flow restoration in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:571–578. doi: 10.1172/JCI9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi T, Kalka C, Masuda H, et al. Ischemia- and cytokine-induced mobilization of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells for neovascularization. Nat Med. 1999;5:434–438. doi: 10.1038/7434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takakura N, Watanabe T, Suenobu S, et al. A role for hematopoietic stem cells in promoting angiogenesis. Cell. 2000;102:199–209. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peichev M, Naiyer AJ, Pereira D, et al. Expression of VEGFR-2 and AC133 by circulating human CD34(+) cells identifies a population of functional endothelial precursors. Blood. 2000;95:952–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Wynter EA, Buck D, Hart C, et al. CD34+AC133+ cells isolated from cord blood are highly enriched in long-term culture-initiating cells, NOD/SCID-repopulating cells and dendritic cell progenitors. Stem Cells. 1998;16:387–396. doi: 10.1002/stem.160387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin AH, Miraglia S, Zanjani ED, et al. AC133, a novel marker for human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 1997;90:5002–5012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziegler BL, Valtieri M, Porada GA, et al. KDR receptor: a key marker defining hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1999;285:1553–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urbich C, Heeschen C, Aicher A, Dernbach E, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Relevance of monocytic features for neovascularization capacity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2003;108:2511–2516. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096483.29777.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Palma M, Venneri MA, Roca C, Naldini L. Targeting exogenous genes to tumor angiogenesis by transplantation of genetically modified hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2003;9:789–795. doi: 10.1038/nm871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohde E, Bartmann C, Schallmoser K, et al. Immune cells mimic the morphology of endothelial progenitor colonies in vitro. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1746–1752. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoder MC, Mead LE, Prater D, et al. Redefining endothelial progenitor cells via clonal analysis and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell principals. Blood. 2007;109:1801–1809. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-043471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capoccia BJ, Shepherd RM, Link DC. G-CSF and AMD3100 mobilize monocytes into the blood that stimulate angiogenesis in vivo through a paracrine mechanism. Blood. 2006;108:2438–2445. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-013755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangi AA, Noiseux N, Kong D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells modified with Akt prevent remodeling and restore performance of infarcted hearts. Nat Med. 2003;9:1195–1201. doi: 10.1038/nm912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mirotsou M, Zhang Z, Deb A, et al. Secreted frizzled related protein 2 (Sfrp2) is the key Akt-mesenchymal stem cell-released paracrine factor mediating myocardial survival and repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1643–1648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610024104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung SC, Pochampally RR, Chen SC, Hsu SC, Prockop DJ. Angiogenic effects of human multipotent stromal cell conditioned medium activate the PI3K-Akt pathway in hypoxic endothelial cells to inhibit apoptosis, increase survival, and stimulate angiogenesis. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2363–2370. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Au P, Tam J, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells facilitate engineering of long-lasting functional vasculature. Blood. 2008;111:4551–4558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-118273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, et al. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Storms RW, Trujillo AP, Springer JB, et al. Isolation of primitive human hematopoietic progenitors on the basis of aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9118–9123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hess DA, Meyerrose TE, Wirthlin L, et al. Functional characterization of highly purified human hematopoietic repopulating cells isolated according to aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Blood. 2004;104:1648–1655. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hess DA, Wirthlin L, Craft TP, et al. Selection based on CD133 and high aldehyde dehydrogenase activity isolates long-term reconstituting human hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2006;107:2162–2169. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hess DA, Craft TP, Wirthlin L, et al. Widespread nonhematopoietic tissue distribution by transplanted human progenitor cells with high aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Stem Cells. 2008;26:611–620. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentry T, Foster S, Winstead L, Deibert E, Fiordalisi M, Balber A. Simultaneous isolation of human BM hematopoietic, endothelial and mesenchymal progenitor cells by flow sorting based on aldehyde dehydrogenase activity: implications for cell therapy. Cytotherapy. 2007;9:259–274. doi: 10.1080/14653240701218516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagano M, Yamashita T, Hamada H, et al. Identification of functional endothelial progenitor cells suitable for the treatment of ischemic tissue using human umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2007;110:151–160. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-047092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingram DA, Mead LE, Tanaka H, et al. Identification of a novel hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells using human peripheral and umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2004;104:2752–2760. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou P, Hohm S, Capoccia B, et al. Immunodeficient mouse models to study human stem cell-mediated tissue repair. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;430:213–225. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-182-6_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Josephson L, Tung CH, Moore A, Weissleder R. High-efficiency intracellular magnetic labeling with novel superparamagnetic-Tat peptide conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 1999;10:186–191. doi: 10.1021/bc980125h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maxwell DJ, Bonde J, Hess DA, et al. Fluorophore conjugated iron oxide nanoparticle labeling and analysis of engrafting human hematopoietic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:517–524. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ceradini DJ, Kulkarni AR, Callaghan MJ, et al. Progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by hypoxic gradients through HIF-1 induction of SDF-1. Nat Med. 2004;10:858–864. doi: 10.1038/nm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corti S, Locatelli F, Papadimitriou D, et al. Identification of a primitive brain-derived neural stem cell population based on aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Stem Cells. 2006;24:975–985. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schatteman GC, Awad O. In vivo and in vitro properties of CD34+ and CD14+ endothelial cell precursors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;522:9–16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0169-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Awad O, Dedkov EI, Jiao C, Bloomer S, Tomanek RJ, Schatteman GC. Differential healing activities of CD34+ and CD14+ endothelial cell progenitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:758–764. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000203513.29227.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phinney DG, Prockop DJ. Concise review. Mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells: the state of transdifferentiation and modes of tissue repair—current views. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2896–2902. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells: the International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, et al. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res. 1999;85:221–228. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ceradini DJ, Gurtner GC. Homing to hypoxia: HIF-1 as a mediator of progenitor cell recruitment to injured tissue. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin DK, Shido K, Kopp HG, et al. Cytokine-mediated deployment of SDF-1 induces revascularization through recruitment of CXCR4+ hemangiocytes. Nat Med. 2006;12:557–567. doi: 10.1038/nm1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peled A, Petit I, Kollet O, et al. Dependence of human stem cell engraftment and repopulation of NOD/SCID mice on CXCR4. Science. 1999;283:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hess D, Li L, Martin M, et al. Bone marrow-derived stem cells initiate pancreatic regeneration. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:763–770. doi: 10.1038/nbt841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aranguren XL, McCue JD, Hendrickx B, et al. Multipotent adult progenitor cells sustain function of ischemic limbs in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:505–514. doi: 10.1172/JCI31153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaplan RN, Rafii S, Lyden D. Preparing the “soil”: the premetastatic niche. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11089–11093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tateishi-Yuyama E, Matsubara H, Murohara T, et al. Therapeutic angiogenesis for patients with limb ischaemia by autologous transplantation of bone-marrow cells: a pilot study and a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:427–435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Assmus B, Honold J, Schachinger V, et al. Transcoronary transplantation of progenitor cells after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1222–1232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janssens S, Dubois C, Bogaert J, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived stem-cell transfer in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:113–121. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67861-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schachinger V, Erbs S, Elsasser A, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1210–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenzweig A. Cardiac cell therapy: mixed results from mixed cells. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1274–1277. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe068172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.