Abstract

Objective

To set investment priorities in global mental health research and to propose a more rational use of funds in this under-resourced and under-investigated area.

Methods

Members of the Lancet Mental Health Group systematically listed and scored research investment options on four broad classes of disorders: schizophrenia and other major psychotic disorders, major depressive disorder and other common mental disorders, alcohol abuse and other substance abuse disorders, and the broad class of child and adolescent mental disorders. Using the priority-setting approach of the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative, the group listed various research questions and evaluated them using the criteria of answerability, effectiveness, deliverability, equity and potential impact on persisting burden of mental health disorders. Scores were then weighted according to the system of values expressed by a larger group of stakeholders.

Findings

The research questions that scored highest were related to health policy and systems research, where and how to deliver existing cost-effective interventions in a low-resource context, and epidemiological research on the broad categories of child and adolescent mental disorders or those pertaining to alcohol and drug abuse questions. The questions that scored lowest related to the development of new interventions and new drugs or pharmacological agents, vaccines or other technologies.

Conclusion

In the context of global mental health and with a time frame of the next 10 years, it would be best to fill critical knowledge gaps by investing in research into health policy and systems, epidemiology and improved delivery of cost-effective interventions.

Résumé

Objectif

Fixer des priorités en matière d’investissement dans la recherche mondiale en santé mentale et proposer un usage plus rationnel des fonds dans ce domaine, qui demeure sous-financé et sous-étudié.

Méthodes

Les Membres du Lancet Mental Health Group ont recensé systématiquement et attribué un score aux options d’investissement dans des recherches concernant quatre classes de troubles : schizophrénie et autres troubles psychotiques majeurs, troubles dépressifs majeurs et autres troubles mentaux courants, abus d’alcool et autres troubles dus à l’abus de substance et troubles de l’enfant et de l’adolescent (classe large). En appliquant la démarche de fixation des priorités de la Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative, le Groupe a listé diverses questions à étudier et les a évaluées selon des critères de résolubilité, d’efficacité, d’aptitude à donner des résultats délivrables, d’équité et d’impact sur la charge persistante de troubles mentaux. Ces scores ont ensuite été pondérés selon le système de valeurs énoncé par un groupe plus important de parties concernées.

Résultats

Les questions à étudier obtenant le score le plus élevé concernaient la recherche sur les politiques et les systèmes de santé, les lieux et les modalités de délivrance des interventions d’un bon rapport coût/efficacité dans les pays à faibles ressources, les recherches épidémiologiques sur la catégorie large des troubles de l’enfant et de l’adolescent et les questions relatives à l’abus d’alcool et de drogues. Les questions obtenant le score le plus bas concernaient le développement de nouvelles interventions, de nouveaux médicaments, agents pharmacologiques et vaccins et d’autres technologies.

Conclusion

Dans le contexte de la santé mentale et à l’horizon des dix prochaines années, il serait préférable de combler les lacunes les plus criantes en matière de connaissances en investissant dans la recherche sur les politiques et les systèmes de santé, l’épidémiologie et l’amélioration de la délivrance des interventions d’un bon rapport coût/efficacité.

Resumen

Objetivo

Establecer las prioridades de inversión en investigaciones mundiales sobre salud mental y proponer un uso más racional de los fondos en este campo subfinanciado e insuficientemente investigado.

Métodos

Miembros del Grupo de Salud Mental Lancet procedieron a enumerar y puntuar sistemáticamente las opciones de inversión en la investigación de cuatro amplias categorías de dolencias: esquizofrenia y otros trastornos psicóticos graves, depresión mayor y otros trastornos mentales comunes, abuso de alcohol y otros trastornos por abuso de sustancias, y la gran variedad de trastornos mentales en niños y adolescentes. Aplicando el criterio de fijación de prioridades de la Iniciativa de Salud del Niño e Investigación Nutricional, el grupo confeccionó una lista de diversos temas de investigación y los evaluó conforme a los criterios de justificación, eficacia, viabilidad, equidad e impacto potencial en la carga persistente de trastornos de salud mental. Las puntuaciones se ponderaron luego de acuerdo con el sistema de valores expresado por un grupo más amplio de interesados directos.

Resultados

Los temas de investigación que obtuvieron una mayor puntuación guardan relación con la investigación de políticas y sistemas de salud, la determinación de dónde y cómo aplicar intervenciones costoeficaces ya existentes en un contexto de pocos recursos, y la investigación epidemiológica relacionada con las categorías generales de trastornos mentales de niños y adolescentes o con aspectos del abuso de alcohol y drogas. Los temas con menor puntuación fueron los relacionados con el desarrollo de nuevas intervenciones y nuevos medicamentos o agentes farmacológicos, vacunas y otras tecnologías.

Conclusión

En el contexto de la salud mental mundial y dentro del horizonte de los próximos 10 años, lo más conveniente sería llenar algunos vacíos de vital importancia en los actuales conocimientos invirtiendo en la investigación de las políticas y los sistemas de salud, la epidemiología y la mejora de la aplicación de intervenciones costoeficaces.

ملخص

الهدف

وضع أولويات الاستثمار في البحوث العالمية في الصحة النفسية، واقتراح المزيد من الاستخدام الرشيد من الأموال في هذه المجالات الشحيحة الموارد والتي تقل الدراسات حولها.

الطريقة

أعد أعضاء مجموعة لانست للصحة النفسية، وبشكل منهجي، قوائم وأحراز (درجات تقييم) لخيارات الاستثمار في البحوث في أربعة أصناف عريضة الطيف من الاضطرابات وهي الفُصام والاضطرابات الذُّهانية الكبرى الأخرى، والاضطراب الاكتئابي الكبير والاضطرابات النفسية الشائعة الأخرى، ومعاقرة الكحول واضطرابات تعاطي المواد المسببة للإدمان، والصنف الواسع الطيف من الاضطرابات النفسية لدى الأطفال والمراهقين. وقد أعدت المجموعة قوائم الأسئلة تتعلق ببحوث مختلفة مع تقديمها باستخدام معايير القدرة على الإجابة، والفعالية، والقدرة على التوصيل، والإنصاف، والأثر المحتمل على استمرار عبء الاضطرابات في الصحة النفسية، وقد أعدت المجموعة ذلك باستخدام أسلوب وضع الأولويات لمبادرة البحوث حول التغذية والصحة لدى الأطفال. وقد وزنت الأحراز وفقاً لنظام قيم يعبر عنها مجموعة أكبر من الأطراف المعنية.

الموجودات

لقد كانت قضايا البحوث التي حازت على أرفع الأحراز (درجات التقييم) تتعلق ببحوث النُظُم والسياسات الصحية، أين وكيف يمكن تقديم التدخلات الموجودة العالية الفعالية لقاء التكاليف في البيئات القليلة الموارد، إلى جانب البحوث الوبائية حول الفئات العريضة المجال التي تتعلق بالاضطرابات النفسية للأطفال والمراهقين أو تلك المتعلقة بقضايا معاقرة الكحوليات والمخدرات أما القضايا التي حازت على أخفض الأحراز فتتعلق بتطوير تدخلات أو أدوية جديدة أو عوامل صيدلانية أو لقاحات أو تكنولوجيات أخرى جديدة.

الاستنتاج

في السياق العالمي للصحة النفسية وضمن الإطار الزمني للسنوات العشرة القادمة سيكون من الأفضل ملء الفجوات الحاسمة في المعارف من خلال الاستثمار في البحوث حول النُظُم والسياسات الصحية والوبائيات إلى جانب تحسين إيتاء التدخلات التي تتسم بفعالية عالية لقاء التكاليف..

Introduction

About 14% of the global burden of disease is attributable to mental disorders.1 Even in sub-Saharan Africa, where communicable diseases are common, mental disorders account for nearly 10% of the total burden of disease.2 Mental disorders are linked to many other health conditions1 and are among the most costly medical disorders to treat.3

Certain treatment and preventive strategies for mental disorders are known to be effective (even in low- and middle income-countries), particularly those for depressive and anxiety disorders and schizophrenia.4,5 However, health systems around the world face a scarcity of financial resources and qualified staff – a situation that is often compounded in low- and middle-income countries by lack of commitment from public health policy makers and inefficient use of resources.6 As a result, measures known to be effective for dealing with mental disorders are often not implemented.

The Global Forum for Health Research has long highlighted the major imbalance between the magnitude of mental health problems (especially in low- and middle-income countries) and the resources devoted to addressing them. This is the so-called “10/90 gap”; that is, only 10% of global spending on health research is directed towards the problems that primarily affect the poorest 90% of the world’s population.7 This gap stunts the development of evidence-based health policies and practice in low- and middle-income countries and limits progress in medicine and public health.8,9 The impact of the gap is particularly evident in the field of mental health, in which the evidence base depends mainly on European and North American cultural norms.10 Recent studies indicate that up to 94% of the published literature in high-impact psychiatric journals is from North America, Europe and Australia/New Zealand,11 with sometimes as little as 3% originating from low- and middle-income countries.11–13

One strategy to redress this imbalance is to invest abundantly in mental health research in low- and middle-income countries. The many possibilities for mental health research in such countries are beyond the capability of any one government or agency to fund; therefore, guidelines are needed to help define priorities for mental health research investments. Since 1990, several initiatives have been designed to set such priorities.14–18 They include the “combined approach matrix” priority-setting tool for health research, which was applied to schizophrenia;17 a 2001 report from the United States National Institute of Mental Health, which outlined three priority areas of research in child and adolescent mental health;19 and Rosenheck’s seven principles for resource allocation in the mental health field.14–20

These attempts to set investment priorities have some limitations: a focus on the generation of new technologies, knowledge and processes, rather than on the implementation of already proven interventions;18 insufficient transparency around the processes and criteria used to derive the suggested investment priorities;19,20 and lack of a clear algorithm and method for linking suggested priorities with future investment decisions.17 The objective of this paper is to address investment priorities in mental health research at the global level and to propose a more rational use of scarce funds in this area by using a systematic method for setting priorities in health research investments recently developed by the Child Health Research Nutrition Initiative (CHNRI).18,21 The method can be applied in different contexts and for different purposes. It has been used to set priorities for zinc-related health research22 and child health priorities at the national level in South Africa.23 It is also currently being implemented by WHO to set global research priorities for eight leading causes of child deaths, and by the International Committee on Child Development to address research priorities to improve child development (Rudan I, personal communication).

Methods

Expert group and context

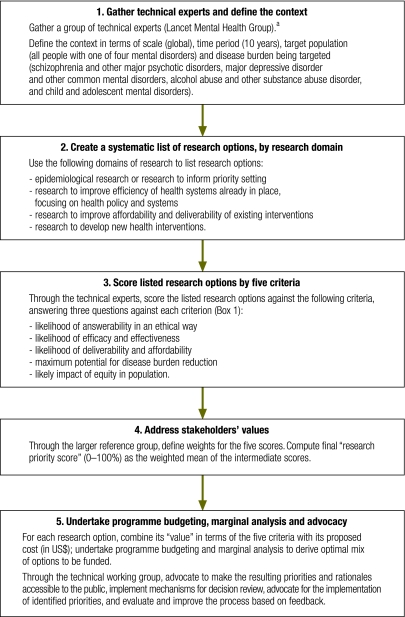

Fig. 1 summarizes the steps involved in applying the CHNRI method. The rationale, conceptual framework and application guidelines for the method have been described in detail elsewhere.18,21–25 In applying the CHNRI method in this study, the first step was to ask a group of leading experts in mental health (n = 39) – the Lancet Mental Health Group – to form a technical working group (Step 1, Fig. 1). The group comprised mainly psychiatrists (74%) but also included psychologists, epidemiologists, an economist, a primary care physician and an anthropologist. It was largely composed of males (77%), and 46% of the members were from low- or middle-income countries.

Fig. 1.

Process for setting research priorities

a Text in parentheses indicates the selections made in this study.

List of research options

Members of the technical working group were then asked to generate a list of research questions by research domain (Step 2, Fig. 1). They proposed a total of 290 questions (not all group members provided questions for all disorders). Many of the questions were either identical or sufficiently similar to allow them to be combined, and three of the authors (MT, VP and SS) synthesized them into a final list of 55 questions. Research investment options were then scored according to the five criteria recommended by the CHNRI to discriminate between suggested research investment options (Step 3, Fig. 1).18,25 Scoring, which was voluntary and took place over a relatively short period, was eventually performed by 24 members (61%) of the working group (other eligible members were unable to complete scoring due to time constraints). The experts who completed scoring had a similar profile (71% psychiatrists, 83% of them male and 38% from low- and middle-income countries) to that of the original larger group.

The experts answered three questions related to each criterion (Box 1), in line with the conceptual CHNRI framework suggested by Rudan et al.25 In this way, the proposed research investment options received five “intermediate scores” (one for each criterion), ranging from 0% to 100%. These values represented a robust measure of the collective view of the experts that the option would satisfy the chosen criterion.

Box 1. Questions used by technical experts to assign intermediate scores to competing research questionsa.

Criterion 1: likelihood that research would lead to new knowledge (enabling development or planning of an intervention) in an ethical way

1. Would you say the research question is well framed and end-points are well defined?

2. Based on the level of existing research capacity in proposed research and the size of the gap from current level of knowledge to the proposed end-points, would you say that a study can be designed to answer the research question and to reach the proposed end-points of the research?

3. Do you think that a study needed to answer the proposed research question would obtain ethical approval without major concerns?

Criterion 2: assessment of likelihood that the intervention resulting from proposed research would be effective

1. Based on the best existing evidence and knowledge, would the intervention that would be developed or improved through the proposed research be efficacious?

2. Based on the best existing evidence and knowledge, would the intervention that would be developed or improved through proposed research be effective?

3. If the answer to either of the previous two questions is positive, would you say that the evidence on which these opinions are based is of high quality?

Criterion 3: assessment of deliverability, affordability and sustainability of the intervention resulting from proposed research

1. Taking into account the level of difficulty with intervention delivery from the perspective of the intervention itself (e.g. design, standardizability, safety), the infrastructure required (e.g. human resources, health facilities, communication and transport infrastructure) and users of the intervention (e.g. need for change of attitudes or beliefs, supervision, existing demand), would you say that the end-points of the research would be deliverable within the context of interest?

2. Taking into account the resources available to implement the intervention, would you say that the end-points of the research would be affordable within the context of interest?

3. Taking into account government capacity and partnership requirements (e.g. adequacy of government regulation, monitoring and enforcement; governmental intersectoral coordination, partnership with civil society and external donor agencies; favourable political climate to achieve high coverage), would you say that the end-points of the research would be sustainable within the context of interest?

Criterion 4: assessment of maximum potential of disease burden reduction

As this dimension is considered “independent” of the others, to score competing options fairly, their maximum potential to reduce disease burden should be assessed as their potential impact fraction under an ideal scenario; that is, when the exposure to targeted disease risk is decreased to 0% or coverage of proposed intervention is increased to 100% (regardless of how realistic that scenario is at the moment – that aspect will be captured by other dimensions of the priority setting process, such as deliverability, affordability and sustainability).

For potential interventions:

Maximum potential to reduce disease burden should be computed as “potential impact fraction” for each proposed research avenue, using the equation:

PIF = [Σ(i = 1 to n) Pi (RRi − 1)] / [Σ(i = 1 to n) Pi (RRi − 1) + 1]

where PIF is the potential impact fraction, i.e. the potential to reduce disease burden through reducing risk exposure in the population from the present level to 0% or increasing coverage by an existing or new intervention from the present level to 100%; RR is the relative risk, given the exposure level (< 1.0 for interventions, > 1.0 for risks), P is the population level of distribution of exposure, and n is the maximum exposure level.

For existing interventions:

Maximum potential to reduce disease burden should be assessed from the results of conducted intervention trials; if no such trials have been undertaken, then it should be assessed as for non-existing interventions, above.

The following questions should then be answered:

1. Taking into account the results of conducted intervention trials (i.e. existing interventions) or, for the new interventions, the proportion of avertable burden under an ideal scenario (i.e. potential interventions), would you say that the successful reaching of research end-points would have a capacity to remove 5% of disease burden or more?

2. To remove 10% of disease burden or more?

3. To remove 15% of disease burden or more?

Criterion 5: assessment of the impact of proposed health research on equity

1. Would you say that the present distribution of the disease burden affects mainly the underprivileged in the population?

2. Would you say that either mainly the underprivileged or all segments of the society equally would be the most likely to benefit from the results of the proposed research after its implementation?

3. Would you say that the proposed research has the overall potential to improve equity in disease burden distribution in the long term (e.g. 10 years)?

Reference group

To ensure involvement of the wider society in directing research investment priorities, we collected opinions from a larger reference group, comprising 43 stakeholders’ representatives, including those from low- and middle-income countries. The process of involving stakeholders in the CHNRI process has been detailed elsewhere.24 The reference group comprised nine psychiatrists, four psychologists, two social workers, three government employees, six nongovernmental organization representatives, six researchers, six users of mental health services and seven members of the public. We contacted members of the group by e-mail and asked them to express their opinions through an electronic questionnaire that described the elements of the process. We asked them to rank the five criteria used for setting priorities. The criterion for effectiveness received the highest rank (2.47), followed by maximum potential for disease burden reduction (2.56), deliverability (3.00), predicted effect on equity (3.28) and answerability (3.70). The next step was to define weights for the five scores for each option (Step 4, Fig. 1). These observed average ranks were then used to compute weights by dividing the expected average rank in the hypothetical situation of all five criteria being equally important (which should be 3.00) by the observed average rank. These weights were subsequently applied to compute intermediate scores. Thus, for each scored research investment option, the intermediate score for effectiveness was increased by 21% (i.e. 3.00/2.47 = 121%) and for maximum potential for disease burden reduction, by 17%; the score for deliverability did not change; and the intermediate scores for equity were decreased by 9% and for answerability, by 19%. The weighted mean of the five intermediate scores represented the overall “research priority score”, which also ranged from 0 to 100%.

Computation and assessment

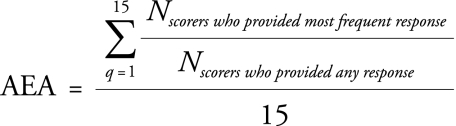

It was not appropriate to use Kappa statistics to assess greatest agreement and greatest controversy because the data sets produced allowed for missing responses, “undecided” responses and different number of experts scoring different criteria.26 Instead, for each research investment option, we reported the average proportion of scorers that agreed on the 15 questions asked. This average expert agreement (AEA) was computed for each scored research investment option as:

|

where q is a question that experts are being asked in order to rank competing research investment options from 1 to 15.

For each evaluated research investment option, the AEA shows the proportion of scorers who gave the same most frequent answer to an average question (e.g. when the average expert agreement is about 60%, this means that for an average question related to a specific research investment option, three out of five scorers gave the most frequent answer).

Results

Table 1 and Table 2 show the final results (10 highest and 10 lowest priorities) of the scoring process used by the technical experts, broken down by type of disorder. Appendix A (available at: http://academic.sun.ac.za/psychology/english/TomlinsonM.htm) shows the final scores of all proposed research options. The five that scored highest all addressed either health policy and systems research options, epidemiological research or research to inform priority setting. The only exception in the 10 highest-scoring research priority options was the one ranked ninth, which proposed the development of a new intervention. All of the five highest-scoring research options addressed either alcohol and drug abuse or child and adolescent mental disorders.

Table 1. Ten mental health research questions given highest priority by members of the Lancet Mental Health Group, 2008a.

| Rank | Research question | Percentage |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disorder | Answerable? | Effective? | Deliverable? | Maximum impact? | Equitable? | Weighted score | Agreement | ||||

| 1 | What HPSR is needed to determine the most effective intersectoral (social, economic and population-based) strategies for reducing consumption in high-risk groups (particularly men), thus reducing the burden of alcohol abuse? | A/DA | 90.8 | 88.8 | 85.8 | 81.0 | 73.3 | 85.9 | 76.0 | ||

| 2 | What training, support and supervision will enable existing maternal and child health workers to recognize, and provide basic treatment for, common maternal, child and adolescent mental disorders? | C/AMD | 97.2 | 80.8 | 89.8 | 59.8 | 87.0 | 83.3 | 78.5 | ||

| 3 | What are the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of school-based interventions, including for children with special needs? | C/AMD | 95.2 | 76.5 | 91.2 | 59.2 | 87.3 | 82.0 | 78.6 | ||

| 4 | What HSPR is needed to estimate the effects of integrating management of child and adolescent mental disorders with that of other child and adolescent physical diseases, including poor nutrition? | C/AMD | 94.4 | 75.5 | 84.3 | 66.3 | 84.3 | 81.4 | 73.8 | ||

| 5 | How effective are early detection and simple, brief treatment methods that are culturally appropriate, implemented by non-specialist health workers in the course of routine primary care, and can be scaled up? | A/DA | 93.3 | 78.4 | 88.3 | 59.6 | 83.3 | 81.1 | 78.5 | ||

| 6 | What is the cost effectiveness of trials of interventions for CMD in primary and secondary care? | CMD | 95.5 | 87.7 | 79.4 | 60.0 | 74.2 | 80.3 | 73.4 | ||

| 7 | What HSPR is needed to develop effective and cost-effective methods for delivering family interventions in low-resource settings to decrease relapses? | S/PSYCH | 96.8 | 83.9 | 79.4 | 61.7 | 74.2 | 80.0 | 77.9 | ||

| 8 | What HSPR is needed to develop feasible, effective and cost-effective ways of integrating parenting interventions and social skills in early childhood care? | C/AMD | 81.5 | 81.5 | 79.6 | 69.2 | 80.0 | 79.8 | 74.3 | ||

| 9 | How effective are new, culturally appropriate community-level interventions (e.g. family therapy) for child and adolescent mental disorders (including mental retardation and epilepsy)? | C/AMD | 97.2 | 77.6 | 87.0 | 56.3 | 79.2 | 79.7 | 75.3 | ||

| 10 | What is the effectiveness of dispensing antipsychotic medication by general community health workers, to reduce relapse and admission rates in people with psychoses? | S/PSYCH | 92.9 | 72.6 | 80.3 | 66.7 | 80.6 | 79.1 | 73.9 | ||

A/DA, alcohol and drug abuse; C/AMD, child and adolescent mental disorders; CMD, depression and common mental disorders; HPSR, health policy and systems research; S/PSYCH, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. a All the listed research options were scored by technical experts in light of five criteria: (1) their potential to generate new knowledge in an ethical way; (2) the likelihood that the intervention resulting from them would be effective; (3) the deliverability, affordability and sustainability of the intervention resulting from them; (4) the resulting intervention’s maximum potential for reducing the burden of disease; and (5) their potential effect on equity in the population.

Table 2. Ten research questions given lowest priority by members of the Lancet Mental Health Group, 2008a.

| Rank | Research question | Percentage |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disorder | Answerable? | Effective? | Deliverable? | Maximum impact? | Equitable? | Weighted score | Agreement | ||||

| 46 | How effective are new, antipsychotic drugs and delivery methods for improved action and fewer side-effects? | S/PSYCH | 81.7 | 70.5 | 31.7 | 49.2 | 53.3 | 58.0 | 66.8 | ||

| 47 | How effective are new techniques for early detection and management of schizophrenia? | S/PSYCH | 77.8 | 52.7 | 42.5 | 46.5 | 63.9 | 56.5 | 59.0 | ||

| 48 | What new, innovative and appropriate interventions can be designed to reduce poor mental health outcomes in at-risk children? | C/AMD | 64.8 | 41.3 | 55.9 | 46.1 | 70.8 | 55.4 | 55.0 | ||

| 49 | What are the benefits of a simpler classification of depressive and anxiety disorders in practice? | CMD | 72.1 | 52.3 | 58.3 | 37.9 | 55.4 | 55.0 | 53.5 | ||

| 50 | How effective are new drugs for the prevention and treatment of child and adolescent mental disorders such as psychosis? | C/AMD | 71.2 | 43.9 | 44.8 | 58.2 | 56.0 | 55.0 | 58.0 | ||

| 51 | How can large-scale, efficient and ethically sound drug discovery research be carried out in LAMI countries? | S/PSYCH | 61.9 | 56.9 | 44.2 | 47.5 | 56.6 | 54.2 | 52.9 | ||

| 52 | How effective are inexpensive, naturally occurring or pharmacological agents that make alcohol intake very unpleasant? (E.g. some antidepressants are used for smoking cessation) | A/DA | 78.4 | 50.0 | 55.3 | 27.2 | 64.9 | 54.1 | 59.4 | ||

| 53 | What are the benefits of new and innovative promotion and prevention programmes? | CMD | 60.8 | 40.0 | 55.8 | 50.8 | 49.2 | 51.6 | 54.1 | ||

| 54 | How effective are new, innovative interventions for alcohol and drug abuse that target biological vulnerability or predisposition, and the interplay between genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in causation and recovery? | A/DA | 62.1 | 47.1 | 42.2 | 49.0 | 50.9 | 50.7 | 52.9 | ||

| 55 | What are the benefits of researching indigenous or local treatments (including non-traditional approaches such as acupuncture and herbal remedies) as potential treatments? | S/PSYCH | 61.9 | 27.4 | 51.8 | 18.4 | 59.5 | 42.2 | 59.6 | ||

A/DA, alcohol and drug abuse; C/AMD, child and adolescent mental disorders; CMD, depression and common mental disorders; HPSR, health policy and systems research; LAMI, low- and middle-income; S/PSYCH, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. a All the listed research options were scored by technical experts in light of five criteria: (1) their potential to generate new knowledge in an ethical way; (2) the likelihood that the intervention resulting from them would be effective; (3) the deliverability, affordability and sustainability of the intervention resulting from them; (4) the resulting intervention’s maximum potential for reducing the burden of disease; and (5) their potential effect on equity in the population.

Of the 10 lowest-scoring research options, seven proposed developing new interventions and technologies (Table 2). Several of the options also targeted the development of new interventions and new drugs or pharmacological agents, vaccines or other technologies. Of the top 10 options, the only one that addressed pharmacological agents (Evaluate the effectiveness of dispensation of anti-psychotic medication by general community health workers in order to reduce relapse and admission rates) was actually concerned with health systems and epidemiological research.

When the scores were broken down by type of disorder, a similar pattern emerged, with health systems and epidemiological research predominating in the highest-scoring research options for each disorder. New interventions that scored highly were those predominantly focused on community, social, behavioural and prevention strategies.

The priorities for the competing investment options varied widely – research priority scores ranged from 42.2% to 85.9%. Scores for answerability for the 55 research options were relatively high (the 47 highest priority options all scored above 80%). However, other criteria helped to lower the overall scores. For example, while the research option “to develop new, more efficacious antipsychotic drugs” scored 81.7% on answerability, it scored poorly on deliverability (31.7%). This illustrates the fundamental problem of health system delivery that is characteristic of much of the developing world. The criterion of reducing the burden of disease contributed to low overall scores. Apparently the technical working group felt that, although such a question may be answerable, it is unlikely to have a strong impact in reducing disease.

For the 10 highest priority research investment options, the average expert agreement parameter was 73.4–78.6%. In other words, about three out of four scorers gave the same answer to an average question related to those options. This level of agreement is much higher than expected from random assignment of scores 0 or 1 (less than 50% because an “undecided” answer would also be allowed). This shows that the experts agreed on the priorities overall but not on the research investment options at the bottom of the ranking list, for which the average expert agreement parameter was generally 50–60%.

Discussion

To significantly reduce the burden of disease caused by the four priority categories of mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries within the next 10 years, research funding should focus on three areas: health policy and systems research; where and how to deliver existing cost-effective interventions in a low-resource context; and epidemiological research on the broad categories of child and adolescent mental disorders or those pertaining to alcohol and drug abuse. Epidemiological research is important because of the lack of policy-relevant information in the developing world.27

Priority-setting exercises in the mental health field have shown that, for schizophrenia, further research is needed on its burden to families, the cost effectiveness of therapeutic interventions, ways to bridge the treatment gap, and ways to overcome stigmatization and social isolation.17 The 2001 report from the US National Institute of Mental Health outlined three priority areas of research in child and adolescent mental health: developing new interventions, moving from efficacy to effectiveness in intervention development, and moving from effectiveness to dissemination in intervention deployment.19 These exercises all resulted in broad, general recommendations. Although few would disagree with their overall messages, they rarely provide specific guidance on how to distribute resources for health research. In contrast, the CHNRI approach generates specific outcomes and suggestions, since it lists concrete research options and assigns them priority scores. The scores provide information about the risk associated with each specific investment in health research, under the assumption that reducing the disease burden is the main expected end-point. Policy makers can then invest in a mixed portfolio of health research investments with a variety of risk levels while respecting the values of wider society.

A recent review highlighted the scarcity of trials testing interventions for the treatment or prevention of mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries,5 especially in the areas of child and adolescent mental disorders and of alcohol and substance abuse disorders. As an example, the review uncovered only 11 trials on alcohol dependence or harmful use and only five trials on mental retardation. In addition, despite the large and increasing burden of substance use disorders in developing countries, 34% of all low- and middle-income countries lack a substance abuse policy.27 According to Rajendram et al., nearly 58% of all research papers on alcohol abuse come from Canada and the United States of America, 30% from Western Europe, and 10% from Australia, Japan, or New Zealand, while the rest of the world, which has 87% of the disease burden, contributes only 8%.28 Furthermore, a recent review showed that of all psychiatric disorders, alcohol and drug abuse had the widest treatment gap (78.1%).

The results of the prioritization exercise described in this paper, in which the top seven research options related to alcohol and substance abuse and to child and adolescent mental disorders, perhaps reflect how these themes have been ignored. They provide evidence of the need to implement health systems research in mental health and carry out epidemiological research in low- and middle-income countries.

The predominance of research on new interventions, particularly against drug-related problems, among the low-priority options is consistent with findings from other exercises based on the CHNRI approach.22,23 In these studies, research on health policy and systems scored highly because of its perceived ability to achieve the largest equitable gains in reducing disease burden over a reasonably short time frame, a criterion specified before the scoring was undertaken. This finding contrasts with trends in the allocation of most research funding and with the United States National Institute of Mental Health’s stated main priority for research into child and adolescent mental health, which is the development of new interventions.19 To be successful, even new, highly effective pharmacological treatments need well-functioning health systems to deliver them and psychosocial interventions to accompany them.23

The expert working group listed few research questions that addressed primary prevention, perhaps due to the difficulty of framing research questions on prevention in a form that could be scored against the five chosen criteria. Also, where such questions were listed, they were not given high priority, perhaps because the context within which scoring was taking place was initially specified as “overall global burden, with the improvements expected over a time frame of the next 10 years”. The CHNRI process highlighted the experts’ general lack of optimism that preventive interventions could be effective or make a real difference to mental health globally.

It is possible that the experts in the working group were systematically more biased against preventive investment options or new interventions than against other categories. However, the group chosen for this exercise was the largest and the most diverse ever to conduct a CHNRI exercise to date. It is thus unlikely that a different group of experts would have arrived at quite different results. Nevertheless, the CHNRI approach could be subject to expert opinion bias because different groups may have different opinions. An advantage of the CHNRI method over previous priority-setting reports14–18 is that potential biases are made transparent in the scoring process. Furthermore, the larger and more diverse the group of chosen experts, the lower the likelihood that scores would significantly deviate from those assigned by a different group of experts. Another limitation of this study was that the research topics were chosen by a self-selected group of professionals – albeit a diverse and senior one – and that the choice of four disorders is not exhaustive, although it does represent a significant part of the disease burden of mental disorders worldwide.

Despite the limitations, this study clearly shows a need to invest in research on the implementation of existing interventions and ways to overcome health system constraints in developing countries. ■

Funding: The Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative, a non-profit effort of the Global Forum for Health Research, covered the expenses of several workshops and conferences at which the methodology was being developed and provided support to Igor Rudan for his assistance in developing the methodology and its application within the area of their expertise.

Competing interests: None declared.

a Possible answers: yes = 1; no = 0; informed but undecided answer: 0.5; not sufficiently informed: blank.

References

- 1.Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet 2007;370:859-77.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein DJ, Seedat S. From research methods to clinical practice in psychiatry: challenges and opportunities in the developing world. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19:573–81. doi: 10.1080/09540260701563536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel V, Araya R, Chaterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, DeSilva M, et al. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low income and middle income countries. Lancet. 2007;370:991–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gureje O, Chisholm D, Kola L, Lasebikan V, Saxena S. Cost-effectiveness of an essential mental health intervention package in Nigeria. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:42–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity and inefficiency. Lancet. 2007;370:878–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.10/90 report on health research 2000 [2nd annual report]. Geneva: Global Forum for Health Research; 2000.

- 7.Saxena S, Paraje G, Sharan P, Karam G, Sadana R. The 10/90 divide in mental health research: trends over a 10-year period. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:81–2. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.011221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Western medical journals and the 10/90 problem. CMAJ. 2004;170:5–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lancet Global Mental Health Group Scale up services for mental disorders: A call for action. Lancet. 2007;370:1241–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel V, Sumathipala A. International Representation in Psychiatric Journals: a survey of 6 leading journals. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:406–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.5.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomlinson M, Swartz L. Imbalances in the knowledge about infancy: the divide between rich and poor countries. Infant Ment Health J. 2003;24:547–56. doi: 10.1002/imhj.10078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel V, Kim YR. Contribution of low- and middle-income countries to research published in leading general psychiatry journals, 2002-2004. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:77–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health research. essential link to equity in development Geneva: Council on Health Research for Development;1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Working Group on Priority Setting Priority setting for health research: lessons from developing countries. Health Policy Plan. 2000;15:130–6. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varmus H, Klausner R, Zerhouni E, Acharya T, Daar AS, Singer PA. Grand challenges in global health. Science. 2003;302:398–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1091769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghaffar A, de Francisco A, Matlin S, editors. The combined approach matrix: a priority-setting tool for health research Geneva: Global Forum for Health Research; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudan I, El Arifeen S, Black RE, Campbell H. Childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea: Setting our priorities right. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:56–61. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70687-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoagwood K, Olin S. The NIMH blueprint for change report: Research priorities in child and adolescent mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:760–7. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenheck RA. Principles for priority setting in mental services and their implications for the least well off. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:653–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.5.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudan I, Gibson J, Kapiriri L, Lansang MA, Hyder AA, Lawn J, et al. Setting priorities in global child health research investments: Assessment of principles and practice. Croat Med J. 2007;48:595–604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown KH, Hess SY, Boy E, Gibson RS, Horton S, Osendarp SJ, et al. Setting priorities for zinc-related health research to reduce children’s disease burden worldwide: an application of the CHNRI research priority-setting method. Public Health Nutr. 2008 doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002188. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomlinson M, Chopra M, Sanders D, Bradshaw D, Hendricks M, Greenfield D, et al. Setting priorities in child health research investments for South Africa. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapiriri L, Tomlinson M, Gibson J, Chopra M, El Arifeen S, Black RE, et al. Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative (CHNRI): Setting priorities in global child health research investments: Addressing the values of the stakeholders. Croat Med J. 2007;48:618–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudan I, Chopra M, Kapiriri L, Gibson J, Lansang MA, Carneiro I, et al. Setting priorities in global child health research investments: Universal challenges and conceptual framework. Croat Med J. 2008;49:307–17. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2008.3.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byrt T. How good is that agreement? Epidemiology. 1996;7:561. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199609000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conclusion. In: Disease control priorities related to mental, neurological, developmental and substance abuse disorders Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajendram R, Lewison G, Preedy VR. Worldwide alcohol-related research and the disease burden. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:99–106. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:858–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]