Abstract

Developmental research has demonstrated the harmful effects of peer rejection during adolescence; however, the neural mechanisms responsible for this salience remain unexplored. In this study, 23 adolescents were excluded during a ball-tossing game in which they believed they were playing with two other adolescents during an fMRI scan; in reality, participants played with a preset computer program. Afterwards, participants reported their exclusion-related distress and rejection sensitivity, and parents reported participants’ interpersonal competence. Similar to findings in adults, during social exclusion adolescents displayed insular activity that was positively related to self-reported distress, and right ventrolateral prefrontal activity that was negatively related to self-reported distress. Findings unique to adolescents indicated that activity in the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (subACC) related to greater distress, and that activity in the ventral striatum related to less distress and appeared to play a role in regulating activity in the subACC and other regions involved in emotional distress. Finally, adolescents with higher rejection sensitivity and interpersonal competence scores displayed greater neural evidence of emotional distress, and adolescents with higher interpersonal competence scores also displayed greater neural evidence of regulation, perhaps suggesting that adolescents who are vigilant regarding peer acceptance may be most sensitive to rejection experiences.

Keywords: peer rejection, adolescence, functional magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Extensive developmental research has demonstrated that adolescence is a time characterized by increased importance of peer relationships, sensitivity to rejection and negative psychological outcomes associated with rejection. When young adolescents make the transition to middle school, it is common to spend more time with peers (Csikszentmihalyi and Larson, 1984), place greater value on peers’ approval, advice and opinions (Brown, 1990) and be more concerned about maintaining peer relationships (Parkhurst and Hopmeyer, 1998). During the transition to adolescence, there is also a shift in the behaviors that youth consider to be desirable and necessary to gain social status. For example, peer rejection is a dominant form of negative treatment among peers at this age (Coie et al., 1990), and isolating and ridiculing classmates becomes associated with perceived popularity (Juvonen et al., 2003). As a result, individuals’ sensitivity to rejection is particularly high at this age due to the increased prevalence of these behaviors and the increased importance placed on maintaining peer relationships. The negative effects of social exclusion on psychological adjustment, including links with depression and anxiety (Rigby, 2000, 2003; Isaacs et al., 2001; Graham et al., 2003), and emotionality and social withdrawal (Abecassis et al., 2002) are well documented. In addition, peer rejection can result in adverse mental and physical health outcomes that persist long-term across development (e.g. Rigby, 2000; Prinstein et al., 2005; Lev-Wiesel et al., 2006).

Although peer rejection is common in the lives of most adolescents, individual differences may moderate adolescents’ distress in response to these situations. Specifically, both sensitivity to peer rejection (Downey and Feldman, 1996) and interpersonal competence—a construct measuring social skills that is associated with greater popularity, social self-esteem and friendship intimacy (Buhrmester et al., 1988; Buhrmester, 1990)—are likely to impact adolescents’ responses to being rejected. Research has consistently found self-reported rejection sensitivity to be related to greater behavioral and neural sensitivity to situations of social rejection (Ayduk et al., 2000; Sandstrom et al., 2003; Burklund et al., 2007; Kross et al., 2007; London et al., 2007). However, behavioral research examining individuals with varying levels of interpersonal competence, measured with self-, peer- and parent-reports, has been less consistent, and has suggested two potential relationships linking interpersonal competence and outcomes following experiences with rejection.

First, a series of studies has demonstrated that interpersonally competent adolescents may be less affected by peer rejection. For example, individuals scoring higher on social competence have been shown to have less negative mood shifts following in vivo experiences with rejection (Reijntjes et al., 2006). In addition, research has linked frequent peer rejection with more socially inappropriate and maladaptive behavior (Rubin et al., 1982). Finally, interpersonally competent adolescents have been shown to have higher quality interactions and relationships with peers (Armistead et al., 1995), suggesting that individuals with lower interpersonal competence may have more relational problems with peers in general. In contrast, an additional series of studies has suggested that interpersonally competent adolescents (as measured by popularity or social skills) are more conscious of peer norms and influence, likely because they want to maintain their high status (Allen et al., 2005). Thus, they may be particularly concerned about threats to their acceptance and respond to peer rejection in ways similar to individuals who are high on measures of rejection sensitivity. In addition, children and adolescents with higher social status possess more advanced social cognitive skills including better social reasoning, interpersonal understanding, sensitivity to peers’ emotions (Dekovic and Gerris, 1994), and theory of mind abilities (Slaughter et al., 2002). While these skills are typically adaptive and have even been shown to aid in coping following peer rejection (Reijntjes et al., 2006), heightened ability to reflect on social situations may produce greater sensitivity or stress related to relational problems with peers (Hoglund et al., 2008). Overall, this research suggests that in addition to rejection sensitivity, interpersonal competence is an important factor to examine when trying to understand adolescents’ responses to rejection. Moreover, assessing some of the neural processes underlying the relationship between interpersonal competence and responses to rejection may clarify some of the specific mechanisms (e.g. sensitivity to rejection and regulatory/coping ability) by which interpersonal competence and responses to peer rejection are linked, therefore expanding on the existing body of behavioral work on this topic.

Neuroimaging research related to social exclusion

Despite the heightened salience of social rejection during adolescence, we know little about the underlying neural or cognitive mechanisms that make this experience so emotionally important during this time period. In adults, a series of neuroimaging studies have identified some of the neural correlates underlying the experience of social rejection by examining neural responses to an episode of social exclusion (Eisenberger et al., 2003, 2007). These studies have revealed a network of neural regions associated with the distress of social exclusion, including the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), involved in the ‘unpleasant’ experience of physical pain (Foltz and White, 1962; Rainville et al., 1997; Sawamoto et al., 2000); the insula, associated with visceral pain and negative affective experience (Cechetto and Saper, 1987; Lane et al., 1997; Philips et al., 1997; Aziz et al., 2000; Phan et al., 2004); and the right ventral and right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VPFC/VLPFC), involved in the regulation of distress associated with both physical pain and negative emotional experiences more generally (Hariri et al., 2000; Petrovic and Ingvar, 2002; Lieberman et al., 2004, 2007). These studies have also shown that individuals who feel more socially rejected in their everyday lives, or who score higher on rejection sensitivity, evidence greater dACC activity to rejection-related stimuli (Burklund et al., 2007; Eisenberger et al., 2007).

Follow-up studies have shown that the subgenual portion of the ACC (subACC) also plays a role in experiences with social rejection. This region was shown to be more active upon learning that one was socially accepted vs. rejected (Somerville et al., 2006) and more active among individuals lower in rejection sensitivity (Burklund et al., 2007). Thus activity in this region may be involved in signaling a less-threatening interpretation of a potentially negative stimulus (Kim et al., 2003), which likely helps to regulate the distress related to the experience (Phelps et al., 2004). Together, these findings highlight a network underlying rejection experiences among adults that has not yet been examined among adolescents.

Neuroimaging research examining peer interactions among adolescents

A handful of studies have begun to explore the neural patterns associated with peer interactions more generally. When anticipating feedback from peers who were previously rated to be more likely to provide negative feedback, clinically anxious adolescents—who typically judge themselves as being unaccepted by peers—displayed more activity in the amygdala, a threat-sensitive neural region, than typically developing adolescents (Guyer et al., 2008). This study suggests that clinically anxious adolescents might be more sensitive to expected negative peer feedback. In a separate study, adolescents who self-reported on their ability to resist peer influence were scanned while viewing a series of angry facial expressions. Adolescents who were less resistant to peer pressure displayed greater neural sensitivity to angry faces, suggesting that negative feedback may be particularly salient for individuals who are more sensitive to peer norms or peer pressure (Grosbras et al., 2007). Together these studies suggest that peer interactions are affectively salient to adolescents and this is reflected specifically by amygdala activity.

Goals of the current study

In the current study we simulated peer rejection, using a virtual ball-tossing game called ‘Cyberball’, to identify specific patterns of neural activity related to peer rejection among adolescents. We examined correlations between this neural activity and self-reported distress to explore the neural regions involved in responding to and regulating the distress of rejection. In addition, we explored individual differences in neural responses to rejection associated with self-reported rejection sensitivity and parent-reported interpersonal competence, since rejection sensitivity and interpersonal competence have been shown to be associated with adolescents’ interpretations and experiences of distress in real-life situations of peer rejection in different ways.

In response to social exclusion, we hypothesized that adolescents would display dACC and insula activity, and that the activity in these regions would be associated with subjective ratings of distress resulting from the experience of being rejected. Given that the cingulate and insular regions of the brain should be functioning at an adult level by adolescence (e.g. Gogtay et al., 2004), we based this prediction on previous findings among adults experiencing social exclusion. However, given the well-established differences between adults and adolescents in terms of the salience of peer rejection experiences, we also considered the possibility that adolescents might show activity in additional regions; for example they might display activity in the amygdala or other regions that have shown robust activations among adolescents engaging in emotionally threatening tasks, due to the enhanced sensitivity to peer interactions during adolescence (see Nelson et al., 2005). In addition, we hypothesized that adolescents would display activation in areas including the right VLPFC and/or right VPFC in response to exclusion vs. inclusion, providing evidence of neural-affective regulation of distress. However, we also predicted that adolescents might display diffuse patterns of activity in this region due to the immaturity of the prefrontal cortex during adolescence (Durston and Casey, 2005; Durston et al., 2006), as well as neural responses in alternate areas that are also theorized to support regulation. Indeed, based on evidence that synaptic pruning of the PFC continues throughout adolescence and that full maturity of this region is not complete until the late 20s (e.g. Gogtay et al., 2004; Sowell et al., 2004), several theorists have recently suggested that PFC regulation of responses to peer interactions may be somewhat hindered during this developmental period (Nelson et al., 2005; Steinberg, 2008). Thus, we considered this possibility that multiple brain regions might aid in regulatory processes among our sample of young adolescents.

In terms of individual differences in how adolescents responded to an experience of peer rejection, we first expected that adolescents who reported being more sensitive to rejection would display more evidence of sensitivity to rejection at the neural level (e.g. more dACC and insula activity). Next, given the diversity of the research related to how interpersonal competence may impact responses to peer rejection, our goal was to examine whether parent-reported interpersonal competence might relate to neural activity following an experience with peer rejection and determine the direction of this potential relationship. Based on previous research there were two possibilities; first, to the extent that higher interpersonal competence is associated with reduced sensitivity to rejection (e.g. Reijntjes et al., 2006), adolescents with higher interpersonal competence scores might show less evidence of sensitivity to rejection at the neural level (e.g. less dACC and insula activity), and potentially less activation in prefrontal regulatory regions if these adolescents were less distressed by the rejection and thus required less regulation of distress. Alternatively, to the extent that higher interpersonal competence is associated with heightened sensitivity to negative peer interactions (e.g. Hoglund et al., 2008) coupled with a better ability to cope with rejection (e.g. Reijntjes et al., 2006), adolescents with higher interpersonal competence scores might show more evidence of sensitivity to rejection at the neural level (e.g. more dACC and insula activity) as well as greater activity in prefrontal and other regulatory regions. As a whole, examining these two possibilities regarding the relationship between interpersonal competence and responses to peer rejection using fMRI will be particularly helpful in determining how the combination of underlying neural distress responses in relation to underlying neural regulatory responses contributes to the overall subjective experience for an individual in a situation of peer rejection.

METHODS

Participants

Participants included an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample of 23 adolescents (14 females) from the greater Los Angeles area. All participants had attended at least one year of middle school and ranged in age from 12.4–13.6 years (M = 13.0); boys and girls did not differ in terms of their mean age. This age range was chosen based on previous research characterizing the middle-school transition as a time of heightened salience of peer relationships resulting from both concern about peer acceptance as well as increased prevalence of peer rejection (e.g. Brown, 1990). Participants came from a variety of ethnic backgrounds, including 52% Caucasian, 26% Latino, 9% African-American, 9% Asian and 4% Native American. Ethnic distributions for boys and girls were similar; 78% of boys were Caucasian and 22% were Latino, while 50% of girls were Caucasian, 29% were half-Caucasian, and 21% were Latino, African-American or Asian.

Participants were recruited through mass mailings, summer camps and fliers distributed in the community. All participants and parents provided assent/consent to participate in the study, which was approved by UCLA's Institutional Review Board.

Procedures

Behavioral measures

During an initial visit, at least one day prior to the completion of the fMRI scan, adolescents’ parents completed the Interpersonal Competence Scale (ICS; Cairns et al., 1995), using a 7-point scale with higher numbers indicating greater competence. The ICS assesses adolescents’ social success at school, including time spent with friends, popularity with same and opposite sex peers, and involvement in social activities. The ICS has been extensively tested and validated as a parent and/or teacher report of interpersonal competence among children and adolescents ranging from ages 9 to 13, and has demonstrated good test-retest reliability and high correlations with both direct observations of social behavior as well as peer nominations of social status (Cairns et al., 1985; Cairns and Cairns, 1994, 1995). In addition, several recent studies have further demonstrated that the ICS is highly associated with both self- and peer-reports of social competence (Xie et al., 2002), and highly predictive of adolescents’ social behaviors (Cadwallader and Cairns, 2002).

On the day of the fMRI scan, adolescents completed the Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire for Children (RSQ; Downey and Feldman, 1996), which assesses the importance of being socially accepted as well as anxiety and beliefs about the likelihood of being accepted, on a scale ranging from 1 = ‘not at all anxious’/‘expect to be accepted’, to 6 = ‘very anxious’/‘expect to be rejected’. Immediately following completion of the Cyberball task, in order to measure distress associated with the exclusion condition, adolescents completed the Need-Threat Scale (NTS; Williams et al., 2000, 2002) which assesses 12 subjectively experienced consequences of being excluded during the game, including ratings of self-esteem (‘I felt liked’), belongingness (‘I felt rejected’), meaningfulness (‘I felt invisible’) and control (‘I felt powerful’), on a scale ranging from 1 = ‘not at all’ to 5 = ‘very much’.

fMRI paradigm

In order to simulate peer rejection during an fMRI scan, we used the Cyberball game. Cyberball is an experimental paradigm that simulates a real interactive experience of social exclusion (Williams et al., 2000, 2002), and it has been used successfully in several previous neuroimaging studies with adults to simulate the experience of being excluded by others (Eisenberger et al., 2003, 2007). We chose this simulated experience of social exclusion as a proxy for peer rejection based on research indicating that during early adolescence, isolating peers from social groups is one of the dominant methods used to reject peers (Coie et al., 1990). In addition, the same Cyberball paradigm used in the current study has been used with success in previous research with adolescents, in order to simulate peer rejection and create feelings of social isolation (Gross, 2007).

During the Cyberball game, participants were told that they were playing a ball-tossing game via the internet with two other adolescents in other scanners, in order to examine coordinated neural activity. In actuality, these other ‘players’ were controlled by the computer. On a computer screen displayed through fMRI compatible goggles, participants saw the cartoon images representing these other players, as well as a cartoon image of their own ‘hand’ that they controlled using a button-box. Throughout the game the ball is thrown back and forth among the three players, with the participant choosing the recipient of their own throws using a button-box, and the throws of the other two ‘players’ determined by the pre-set program.

Participants played two rounds of Cyberball during two separate fMRI scans: one round in which they were ‘included’ throughout the game, and one round in which they were ‘excluded’ by the other participants. Throughout the inclusion round the computerized players were equally likely to throw the ball to the participant or the other player. However, during the exclusion round, the two computerized players stopped throwing the ball to the participant after the participant had received a total of 10 throws, and threw the ball only to each other for the remainder of the game. Each round of Cyberball consisted of 60 ball tosses total, including all the participants’ tosses as well as the tosses of the two simulated players. Thus, the exclusion portion of the second round, following the participant's first 10 throws, consisted of half of the total number of ball tosses and lasted for approximately half of the round or about 60 s (depending on the time that it took each participant to throw the ball after having received it).

Following the completion of the NTS questionnaire at the end of the fMRI session, participants were given a full debriefing explaining the deception involved in the Cyberball game and thoroughly questioned about their feelings regarding this deception. During the debriefing session, participants were also probed to determine whether they had believed the manipulation. Three of the 23 participants expressed suspicions about whether the other players were real after being scanned, and two participants stated that they thought there was a problem with their computer or button-box that had resulted in their exclusion. The remaining 18 participants believed the deception and did not indicate that they were suspicious prior to being debriefed.

fMRI data acquisition

Images were collected using a Siemens Allegra 3-Tesla MRI scanner. Adolescents were given extensive instructions to decrease motion, and head motion was restrained with foam padding and surgical tape. One subject of the original 24 was excluded due to motion in excess of 1.5 mm, resulting in the final sample of 23 participants. The Cyberball task was presented on a computer screen, which was projected through scanner-compatible goggles.

For each participant, an initial 2D spin-echo image (TR = 4000 ms, TE = 40 ms, matrix size 256 × 256, 4 mm thick, 1 mm gap) in the sagittal plane was acquired in order to enable prescription of slices obtained in structural and functional scans. In addition, a high-resolution structural scan (echo planar T2-weighted spin-echo, TR = 4000 ms, TE = 54 ms, matrix size 128 × 128, FOV = 20 cm, 36 slices, 1.56 mm in-plane resolution, 3 mm thick) coplanar with the functional scans was obtained for functional image registration during fMRI analysis preprocessing. Each of the two rounds of Cyberball was completed during a functional scan lasting 2 min, 48 s (echo planar T2*-weighted gradient-echo, TR = 2000 ms, TE = 25 ms, flip angle = 90°, matrix size 64 × 64, 36 axial slices, FOV = 20 cm; 3 mm thick, skip 1 mm).

fMRI data analysis

All neuroimaging data was preprocessed and analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM5; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, Institute of Neurology, London, UK). Preprocessing for each individual's images included image realignment to correct for head motion, normalization into a standard stereotactic space as defined by the Montreal Neurological Institute and the International Consortium for Brain Mapping, and spatial smoothing using an 8 mm Gaussian kernel, full width at half maximum, to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. Cyberball was modeled as a block design. Each round of Cyberball was modeled as a run with each period of inclusion and exclusion modeled as a block within the run for a total of two inclusion blocks (one during the first run and one during the first half of the second run) and one exclusion block. The initial rest and final rest during the first run, as well as the initial rest during the second run were not modeled, in order to maintain an implicit baseline. The final rest during the second run was not included in the implicit baseline, as brain activity immediately following exclusion might continue to reflect activity related to the exclusion experience. Because the paradigm is self-advancing for each participant, block lengths varied slightly across individuals, and final rest periods allowed for this variation within a functional scan lasting a set amount of time. After modeling the Cyberball paradigm, linear contrasts were calculated for each planned condition comparison for each participant. These individual contrast images were then used in whole-brain, group-level, random-effects analyses across all participants.

In order to test the primary research questions, the following group-level tests were run at each voxel across the entire brain volume: (a) direct comparisons between exclusion and inclusion; (b) examination of differences between exclusion and inclusion that were dependent on individuals’ self-reported distress scores from the NTS; (c) examination of differences between exclusion and inclusion that were dependent on individuals’ self-reported rejection sensitivity scores from the RSQ; and (d) examination of differences between exclusion and inclusion that were dependent on individuals’ parent-reported interpersonal competence scores from the ICS. Reported correlational findings reflect regions of the brain identified using these whole-brain regressions, in which the behavioral variables (NTS, RSQ and ICS) were significantly associated with the difference in activity between exclusion and inclusion. Finally, we examined whether there were gender differences in neural activity during exclusion compared to inclusion.

To examine links between areas hypothesized to play a regulatory role during exclusion (e.g. right VLPFC) and areas linked with the distress experienced during exclusion, we performed interregional correlational analyses across subjects. To do this we extracted parameter estimates from the potentially regulatory regions and entered these as regressors in a whole-brain, random-effects group analysis comparing the exclusion and inclusion conditions. In order to isolate the most relevant regions of interest for this analysis, we identified the local maxima of the areas that were negatively correlated with subjective distress following exclusion, and examined correlations between these specific areas and the regions that had been hypothesized a priori to relate to feelings of subjective distress associated with social exclusion.

All group-level analyses were initially thresholded at P < 0.005 for magnitude (uncorrected for multiple comparisons), with a minimum cluster size threshold of 10 voxels (Forman et al., 1995), in order to examine all regions which have been found to be associated with social and emotional processing (e.g. prefrontal and limbic regions). Subsequently, we used a stricter threshold of P < 0.05 for magnitude (FDR-corrected) to examine all other areas of the brain. All coordinates are reported in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) format.

RESULTS

Behavioral results

Participants’ average scores for self-reported rejection sensitivity (M = 2.78, s.d. = 0.58) ranged from 1.42 to 3.58 out of a possible 6. The mean for boys’ rejection sensitivity (M = 3.11) was slightly higher than for girls (M = 2.57; F = 5.71, P < 0.05). Participants’ average scores for parent-reported interpersonal competence (M = 5.66, s.d. = 0.67) ranged from 4.42 to 7 out of a possible 7, and did not differ by gender. For subjective distress reported immediately following the Cyberball game, participants’ mean score was 2.90 (s.d. = 0.73) and ranged from 1.58 to 4.50 out of a possible 5; these scores also did not differ by gender. Participants’ scores on these three measures were not significantly correlated with each other (all P ≥ 0.20). However, there was a weak positive association between interpersonal competence and rejection sensitivity scores, r(21) = 0.28, P = 0.20. When the five participants who reported being suspicious about the task (either due to suspected computer problems or disbelief in the other players’ existence) were excluded from analyses, the means, standard deviations, ranges and intervariable correlations for each of these variables remained statistically the same. Given that no participants reported being suspicious prior to playing the game, and the lack of differences in behavioral measures including those measured after the scan, these five participants were included in all neuroimaging analyses.

Neural activity during social exclusion compared to inclusion

As predicted, adolescents displayed several regions of activation during the exclusion condition, compared to the inclusion condition, as shown in detail in Table 1. Consistent with data from adult samples, adolescents showed significant activity in the insula and the right VPFC. In addition, significant activation was found in the subACC. Although dACC activity has been found in adult studies of social exclusion (Eisenberger et al., 2003, 2007), there was no evidence of dACC activity among our adolescent population. Next, unlike in previous studies with adults, adolescents also displayed significant activation in the ventral striatum (VS), a region that has been consistently shown to be involved in reward processing (McClure et al., 2003; O’Doherty et al., 2003, 2004; Rodriguez et al., 2006) and more recently has been shown to play a role in emotion regulation as well (Wager et al., 2008). Finally, the main effect of exclusion compared to inclusion was compared across gender groups; however, no meaningful differences between boys and girls emerged in any of the regions predicted to play a role in the experience of exclusion.

Table 1.

Regions activated during the exclusion condition compared to the inclusion condition

| Anatomical region | BA | x | y | z | t | k | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusion > Inclusion | ||||||||

| Insula | R | 50 | −10 | −6 | 3.67 | 25 | < 0.001 | |

| VPFC | 47/10 | R | 24 | 36 | −2 | 3.22 | 45 | < 0.005 |

| Ventral striatum | R | 8 | 8 | −6 | 4.21 | 151 | < 0.0005 | |

| subACC | 25 | R | 8 | 22 | −4 | 4.06 | 151 | < 0.0005 |

Note. BA refers to putative Brodmann's Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y and z refer to MNI coordinates in the left–right, anterior–posterior and interior–superior dimensions, respectively; t refers to the t-score at those coordinates (local maxima). The following abbreviations are used for the names of specific regions: ventral prefrontal cortex (VPFC), subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (subACC).

Neural activity during social exclusion correlated with subjective distress

To examine how subjective distress during social exclusion correlated with neural activity, we examined the whole brain in order to identify the regions in which participants’ self-reported subjective distress scores (after being excluded from the Cyberball game) were associated with the difference between activity during exclusion and activity during inclusion. All regions where activity was related to subjective distress are displayed in Table 2. Individuals who showed greater activity in the insula and subACC reported greater feelings of social distress in response to social exclusion (Figure 1A and B). In addition, activity in certain regions of the PFC was also positively related to social distress. When examining neural activity that was negatively correlated with subjective feelings of distress, significant activity was present in two regions of the right VLPFC (see Figure 2A), consistent with previous research, as well as in the dorsomedial PFC (DMPFC). In addition, a surprising finding revealed that activity in the VS was also negatively correlated with subjective distress (Figure 2B), and therefore was further explored in the section on interregional correlations below.

Table 2.

Regions activated during the exclusion condition compared to the inclusion condition that correlated significantly with self-reported subjective distress (NTS scores)

| Anatomical region | BA | x | y | z | t | r | k | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive associations with subjective distress | |||||||||

| subACC | 25 | L | −6 | 22 | −12 | 3.55 | 0.61 | 27 | < 0.001 |

| Insula | L | −46 | 8 | −4 | 3.72 | 0.63 | 65 | < 0.001 | |

| Insula | L | −34 | 22 | 0 | 3.37 | 0.59 | 16 | < 0.005 | |

| Anterolateral PFC | 10 | L | −24 | 54 | 8 | 6.00 | 0.79 | 257 | < 0.0001 |

| VLPFC | 47 | R | 34 | 20 | −22 | 3.85 | 0.64 | 134 | < 0.0005 |

| Negative associations with subjective distress | |||||||||

| VLPFC | 45 | R | 52 | 36 | 4 | 4.60 | 0.71 | 182 | < 0.0001 |

| VLPFC | 46 | R | 42 | 46 | 14 | 4.41 | 0.69 | 182 | < 0.0005 |

| DMPFC | 8 | R | 22 | 52 | 48 | 3.07 | 0.56 | 10 | < 0.005 |

| Ventral striatum | R | 6 | 4 | −8 | 4.19 | 0.67 | 15 | < 0.0005 | |

Note. BA refers to putative Brodmann's Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y and z refer to MNI coordinates in the left–right, anterior–posterior and interior–superior dimensions, respectively; t refers to the t-score at those coordinates (local maxima); r refers to the correlation coefficient representing the strength of the association between NTS scores and the difference between activity during exclusion and activity during inclusion in the specified region; these correlation values are provided for descriptive purposes. The following abbreviations are used for the names of specific regions: subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (subACC), prefrontal cortex (PFC), ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC).

Fig 1.

Greater distress during exclusion compared to inclusion predicts greater activity in the Insula and subACC. (A) Insula activity during the exclusion condition compared to the inclusion condition that was positively correlated with participants’ self-reported distress. (B) subACC activity during the exclusion condition compared to the inclusion condition that was positively correlated with participants’ self-reported distress. Correlation values listed in scatter plots are provided for descriptive purposes.

Fig 2.

Greater activity in the right VLPFC and VS during exclusion compared to inclusion predicts less subjective distress. (A) Right VLPFC activity during the exclusion condition compared to the inclusion condition that was negatively correlated with participants’ self-reported distress. (B) VS activity during the exclusion condition compared to the inclusion condition that was negatively correlated with participants’ self-reported distress. Correlation values listed in scatter plots are provided for descriptive purposes.

Interregional correlations during exclusion compared to inclusion

Interregional correlational analyses were performed to examine negative correlations between right VLPFC, DMPFC and VS activity and neural activity hypothesized to be related to distress, in order to further explore potential regulatory properties of these three areas. Group-level analyses were performed comparing exclusion to inclusion, with parameter estimates from the active areas of right VLPFC, DMPFC and VS used as individual regressors. With the specific goal of identifying regions that might be negatively related, we focused on interregional correlations between the right VLPFC, DMPFC and VS and the regions found to be positively related to the distress associated with social exclusion in the current study and previous studies with adults (e.g. dACC, insula, subACC).

Two distinct regions of the right VLPFC that were associated with lower levels of distress following exclusion showed negative correlations with areas of the insula, subACC, dACC and amygdala (see Table 3). In addition, the region of the DMPFC that was associated with lower levels of distress following exclusion showed negative correlations with areas of the amygdala, dACC and insula (see Table 3). Thus, right VLPFC and DMPFC may play important roles in regulating distress following exclusion during adolescence. Interestingly, the VS also displayed significant negative correlations with the insula, subACC and dACC, as shown in Table 3, providing further evidence that this region may also be crucial for regulating negative affect during adolescence. Moreover, the VS also showed positive correlations with two areas of the right VLPFC, a finding that has been observed previously (Wager et al., 2008).

Table 3.

Interregional correlations in distress-related regions during exclusion compared to inclusion

| Anatomical region | BA | x | Y | z | t | r | k | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative correlations with right VLPFC (52 36 4) | |||||||||

| subACC | 25 | R | 10 | 20 | −8 | 2.92 | 0.54 | 18 | < 0.005 |

| dACC | 24 | R | 12 | −6 | 44 | 3.35 | 0.59 | 50 | < 0.005 |

| Insula | R | 48 | −2 | 0 | 3.96 | 0.65 | 223 | < 0.0005 | |

| Negative correlations with right VLPFC (42 46 14) | |||||||||

| subACC | 25 | L | −6 | 26 | −12 | 4.12 | 0.67 | 93 | < 0.0005 |

| Amygdala | R | 26 | 0 | −32 | 4.35 | 0.69 | 57 | < 0.0005 | |

| Negative correlations with DMPFC (22 52 48) | |||||||||

| subACC | 25 | L | −6 | 26 | −12 | 4.12 | 0.67 | 93 | < 0.0005 |

| Amygdala | R | 26 | 0 | −32 | 4.35 | 0.69 | 57 | < 0.0005 | |

| Amygdala | L | −14 | −4 | −8 | 7.41 | 0.85 | 318 | < 0.0001 | |

| dACC | 32 | L | −14 | 20 | 30 | 4.88 | 0.73 | 61 | < 0.0001 |

| Insula | L | −42 | 4 | 4 | 3.39 | 0.59 | 37 | < 0.005 | |

| Negative correlations with ventral striatum (6 4 −8) | |||||||||

| subACC | 25 | L | −10 | 22 | −16 | 4.80 | 0.72 | 43305 | < 0.0001 |

| dACC | 32 | L | −12 | 16 | 40 | 4.80 | 0.72 | 43305 | < 0.0001 |

| dACC | 32 | R | 10 | 24 | 38 | 4.73 | 0.72 | 43305 | < 0.0001 |

| Insula | L | −44 | 6 | −6 | 7.47 | 0.85 | 43305 | < 0.0001 | |

| Insula | R | 58 | 2 | 8 | 5.11 | 0.74 | 43305 | < 0.0001 | |

Note. BA refers to putative Brodmann's Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y and z refer to MNI coordinates in the left–right, anterior–posterior and interior–superior dimensions, respectively; t refers to the t-score at those coordinates (local maxima); r refers to the correlation coefficient representing the strength of the association between each VOI and the difference between activity during exclusion and activity during inclusion in the specified regions; these correlation values are provided for descriptive purposes. The significant activity in the subACC, dACC and Insula, were part of the same interconnected cluster at the specified threshold. The following abbreviations are used for the names of specific regions: ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (subACC), dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC).

Neural activity during social exclusion correlated with rejection sensitivity and interpersonal competence

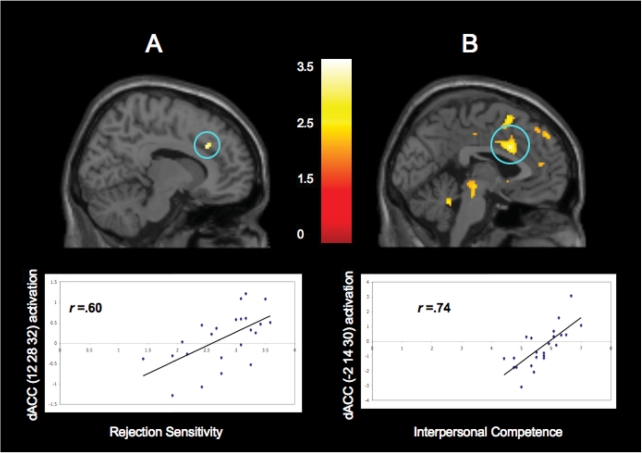

Next, to examine how rejection sensitivity correlated with neural activity, we again examined the whole brain in order to identify the regions in which participants’ rejection sensitivity scores were associated with the difference between activity during exclusion and activity during inclusion. Three significant regions of activation emerged that were positively related to rejection sensitivity, including the dACC (see Figure 3A), which replicates findings among adults showing positive correlations between dACC activity and self-reported rejection sensitivity (Burklund et al., 2007), as well as the precuneus, and the anterolateral PFC (see Table 4). There were no regions that correlated negatively with rejection sensitivity.

Fig 3.

Greater self-reported rejection sensitivity and parent-reported interpersonal competence predict greater activation in the dACC during exclusion compared to inclusion. (A) dACC activity during the exclusion condition compared to the inclusion condition that was positively correlated with participants’ self-reported rejection sensitivity. (B) dACC activity during the exclusion condition compared to the inclusion condition that was positively correlated with participants’ parents’ reports of interpersonal competence. Correlation values listed in scatter plots are provided for descriptive purposes.

Table 4.

Regions activated during the exclusion condition compared to the inclusion condition that correlated significantly with self-reported rejection sensitivity scores and parent-reported interpersonal competence scores

| Anatomical region | BA | x | y | z | t | r | k | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive associations with rejection sensitivity | |||||||||

| dACC | 32 | R | 12 | 28 | 32 | 3.42 | 0.60 | 15 | < 0.005 |

| Anterolateral PFC | 10 | L | −20 | 48 | −10 | 3.74 | 0.63 | 33 | < 0.001 |

| Precuneus | 7 | L | −16 | −66 | 64 | 3.41 | 0.60 | 10 | < 0.005 |

| Positive associations with interpersonal competence | |||||||||

| dACC | 32 | L | −2 | 14 | 30 | 5.10 | 0.74 | 4189 | < 0.0001 |

| subACC | 25/32 | R | 6 | 26 | −10 | 3.32 | 0.59 | 40 | < 0.005 |

| Insula | R | 38 | −16 | 2 | 4.54 | 0.70 | 4189 | < 0.0001 | |

| Insula | R | 34 | 10 | 10 | 3.63 | 0.62 | 4189 | < 0.001 | |

| Insula | L | −34 | −18 | 2 | 4.47 | 0.70 | 751 | < 0.0005 | |

| Insula | L | −36 | 14 | −6 | 3.39 | 0.59 | 16 | < 0.005 | |

| VLPFC | 47 | R | 40 | 48 | −4 | 4.42 | 0.69 | 343 | < 0.0005 |

| VLPFC | 47 | R | 38 | 38 | −18 | 3.87 | 0.65 | 53 | < 0.0005 |

| VLPFC | 47 | L | −48 | 26 | −2 | 3.60 | 0.62 | 38 | < 0.001 |

| VLPFC | 47 | L | −38 | 38 | −18 | 3.54 | 0.61 | 31 | < 0.001 |

| Caudate/ventral striatum | R | 16 | 8 | 2 | 4.22 | 0.68 | 4189 | < 0.0005 | |

| Ventral striatum | L | −4 | 12 | −4 | 3.01 | 0.55 | 11 | < 0.005 | |

| Pregenual ACC | 32 | R | 8 | 40 | 6 | 4.67 | 0.71 | 280 | < 0.0001 |

| DMPFC | 8 | R | 6 | 32 | 50 | 5.59 | 0.77 | 4189 | < 0.0001 |

| DLPFC | 46 | R | 48 | 42 | 16 | 4.47 | 0.70 | 364 | < 0.0005 |

| DLPFC | 8 | R | 40 | 34 | 48 | 3.32 | 0.59 | 16 | < 0.005 |

Note. BA refers to putative Brodmann's Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y and z refer to MNI coordinates in the left–right, anterior–posterior and interior–superior dimensions, respectively; t refers to the t-score at those coordinates (local maxima); r refers to the correlation coefficient representing the strength of the association between each regressor (rejection sensitivity or interpersonal competence) and the difference between activity during exclusion and activity during inclusion in the specified region; these correlation values are provided for descriptive purposes. The significant activity in the dACC, insula, caudate/ventral striatum and DMPFC were part of the same interconnected cluster at the specified threshold. The following abbreviations are used for the names of specific regions: dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), prefrontal cortex (PFC), subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (subACC), ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC).

Finally, to examine how parents’ reports of interpersonal competence were related to neural activity during exclusion compared to inclusion, we performed an additional whole brain analysis to identify the regions in which participants’ interpersonal competence scores were associated with the difference between activity during exclusion and activity during inclusion. Several interesting findings emerged, as shown in Table 4. Significant activation in the dACC and insula (see Figure 3B), as well as in the subACC and pregenual ACC (preACC), was positively related to interpersonal competence scores, suggesting that these neural structures, many of which have been previously found to support experiences of social exclusion in adults, are also particularly sensitive to social exclusion among interpersonally competent adolescents. In addition, individuals higher in interpersonal competence also showed significant activation in the right VLPFC, left VLPFC, DMPFC and VS during exclusion compared to inclusion, suggesting that interpersonally competent adolescents may also be engaging in more regulation of feelings of distress related to exclusion than less interpersonally competent adolescents. There were no regions that correlated negatively with interpersonal competence.

It is worth noting that when all three behavioral measures (subjective distress, rejection sensitivity and interpersonal competence) were included in the same multiple regression model in SPM5, no findings emerged that were substantively different from those found when running the three regressions separately. This suggests that subjective distress, rejection sensitivity and interpersonal competence each independently predict activity in the regions specified above, even after controlling for the contributions of the other two variables.

DISCUSSION

Overall, our results indicate that the neural circuitry associated with either producing or regulating the feelings of distress when being excluded by peers is similar to that which has been found among adults experiencing social exclusion in previous research. However, our findings also indicate that adolescents may experience social exclusion by peers in unique ways. Such a discovery may contribute to our understanding of why peer rejection is so salient during this developmental time period.

As predicted, during exclusion compared to inclusion, adolescents displayed reliable activity consistent with that seen previously among adults, including significant activity in the insula, a region associated with visceral pain and negative affect (Augustine, 1996; Buchel et al., 1998; Gorno-Tempini et al., 2001; Phillips et al., 2003, 2004). Furthermore, analyses suggested that individuals with greater activity in the insula felt more social distress in response to social exclusion, a finding consistent with prior work linking insular activity to neural responses during social exclusion (Eisenberger et al., 2003). Also in line with previous adult studies, adolescents showed activity in the right VLPFC that was related to lower reports of distress, and interregional correlational analyses confirmed right VLPFC activity was negatively correlated with activity in the insula, subACC and dACC, consistent with previous work showing that this region plays a role in regulating negative affect (Hariri et al., 2000; Eisenberger et al., 2003; Lieberman et al., 2004, 2007). Thus, RVLPFC may play an important role in regulating distress following exclusion during adolescence.

Interestingly, there were a few regions that either did not show the same pattern of activity in adolescents as they have in adults or have not been previously observed in studies of social exclusion among adults. For instance, although dACC activity has been consistently shown among adult samples to be related to the distress experienced during social exclusion (e.g. Eisenberger et al., 2003), a similar relationship between dACC activity during exclusion and distress was not found among adolescents. This difference was unexpected; however, it is not surprising given the differences in the salience, prevalence and meaning of social rejection when comparing adults and adolescents. In addition, among adolescents, subACC activity was found during exclusion compared to inclusion and this activity was correlated with higher reports of distress following exclusion. This is contrary to previous work in adults showing that the subACC is involved in more positive affective processes, including social acceptance (Somerville et al., 2006), lower rejection sensitivity (Burklund et al., 2007), optimism (Sharot et al., 2007) and positive interpretations of negative stimuli (Kim et al., 2003). Thus, it is not clear why the subACC is associated with greater self-reported distress in adolescents; however, it should be noted that research with clinical populations has shown reverse effects as well, such that greater subACC activity was associated with higher levels of depression (Chen et al., 2007; Keedwell et al., 2008). It is possible that adolescents may show patterns of subACC activity more similar to clinical samples than adults either because adolescents display greater emotional reactivity than adults, or because of the ongoing development of this region during adolescence (e.g. Gogtay et al., 2004).

Finally, an additional unique finding from this study indicated that adolescents displayed significant activation in the VS during exclusion compared to inclusion, and that VS activity was negatively correlated with subjective distress. An interregional correlational analysis revealed that this area of the VS was negatively correlated with the insula, subACC and dACC, suggesting that this region may be crucial for regulating negative affect during adolescence. Although not predicted, this finding fits with recent work showing that the VS is involved in successful emotion regulation. The VS has consistently been shown to be involved in reward learning and approach motivation more generally (McClure et al., 2003; Schultz, 2004, Tindell et al., 2006; Wager et al., 2007) and in a recent study, greater activity in the VS when reappraising aversive images related to greater reappraisal success (Wager et al., 2008). This previous work supports the hypothesis that VS activity may play a role in affect regulation by aiding in the reinterpretation of stimuli in positive ways. Moreover, the positive associations between the VS and the right VLPFC seen in the current study replicate previous work (Wager et al., 2008) and suggest that these areas could potentially be active simultaneously to aid in affect regulation.

In support of this theory, research in clinical populations among individuals with atypically functioning prefrontal regions (e.g. bipolar patients) has demonstrated that the VS supports regulation of responses to emotionally salient stimuli (e.g. Dickstein and Leibenluft, 2006; Marsh et al., 2007). One interpretation of these clinical findings is that the VS may play a compensatory role for some of the functions typically supported by the prefrontal cortex, and thus VS activity may be heightened among populations with atypically functioning prefrontal regions during tasks requiring regulatory processing. Since the prefrontal cortex continues to develop both structurally and functionally through late adolescence (Giedd et al., 1999; Gogtay et al., 2004; Sowell et al., 2004), and is thus not ‘typically functioning’ relative to adults, the VS may provide an alternate means of regulating negative emotion among typically-developing adolescents, in ways similar to clinical populations. In general, these kinds of discrepancies in frontal lobe maturity may help to explain behavioral differences in responses to emotion-evoking stimuli across ages as well as why certain experiences, like peer rejection, appear to have a developmental time frame during which they are particularly salient and distressing.

In addition to our analyses examining neural correlates of distress and regulation of distress during exclusion by peers, we examined how rejection sensitivity and interpersonal competence modulated neural activity during exclusion. We found that adolescents who reported themselves as being more sensitive to peer rejection displayed greater activity in the dACC, precuneus and anterolateral PFC. This association with the dACC is consistent with previous research with adults indicating that increased activity in the dACC is associated with greater social distress following social exclusion (Eisenberger et al., 2003) and greater rejection sensitivity (Burklund et al., 2007). The precuneus has previously been found to be linked to mentalizing tasks including imagery (Cavanna and Trimble, 2006) and both direct and reflected self-appraisals (Pfeifer et al., in press), and thus our finding supports the possibility that adolescents who are more sensitive to rejection may be more concerned with the other players’ thoughts and motivations for excluding them.

Finally, the association between parent-reported interpersonal competence and neural activity during exclusion revealed that adolescents whose parents perceived them as being more socially competent showed heightened activity in the dACC and insula, two regions found to be related to exclusion in previous research (e.g. Eisenberger et al., 2003). These findings suggest that heightened interpersonal skills among adolescents is linked with increased neural sensitivity to exclusion by peers. Although somewhat counterintuitive, this is consistent with behavioral research indicating that adolescents with high interpersonal competence are more conscious of peer norms, more advanced cognitively, and more sensitive to others’ emotions (Dekovic and Gerris, 1994; Allen et al., 2005), which leaves them more sensitive to relational problems with peers (Hoglund et al., 2008).

Also consistent with this hypothesis, more interpersonally competent adolescents displayed greater activation in the right VLPFC and VS during exclusion, suggesting that interpersonally competent adolescents may also be engaging in more regulation of distress related to being rejected—either because their heightened distress produces a greater need for regulation, or because they are better at regulating. Consistent with the second of these explanations, behavioral research has shown that even interpersonally competent individuals who appear less affected by peer rejection, are actually similarly distressed by rejection; however, they are better able to recover from rejection experiences using problem-solving and reasoning as coping methods that result in a relatively faster attenuation of negative mood than other children (Reijntjes et al., 2006).

Overall these findings suggest that, similar to adolescents who report being more sensitive to rejection, individuals whose parents perceive them to be more interpersonally competent show more neural sensitivity to a simulated experience of peer rejection. Furthermore, in the context of previous research with adults experiencing social exclusion, these findings may suggest that the neural structures that support social exclusion experiences among adults are particularly sensitive to peer exclusion among adolescents who evidence heightened sensitivity to negative social encounters with peers, (i.e. more interpersonal competence and/or rejection sensitivity.

LIMITATIONS

Several aspects of the study and task design could have potentially impacted our findings. First, because it was necessary to create a real social experience with peers, given our interest in feelings of true rejection, we could not include some of the controls that are typical of neuroimaging studies. For example, we could only include one exclusion block in our design, because of the necessity of maintaining an ecologically valid experience. However, given that the lack of additional exclusion blocks actually reduces the probability of Type I errors in our experiment, we are skeptical that this limitation affected our primary findings. Similarly, in order to prevent the expectation of being rejected from confounding our results obtained during the inclusion condition, we could not counterbalance the order of the inclusion and exclusion conditions. Given our specific age range (12–13 years old), which we chose precisely because of the salience of peer relationships at this age, we must also consider the possibility that individual differences in pubertal development impacted our findings. Although pubertal differences were not considered in the current study, young adolescents at this age are likely to be in the midst of puberty, and we cannot ignore the possibility that pubertal maturation influenced both subjective and neural responses to peer rejection. In addition, it is possible that adolescents’ self-reports were biased due to social desirability, given the sensitive nature of being rejected by peers at this age. However, due to the variability of responses and the strong correlation with neural activity in predicted regions, we doubt that this issue significantly affected our results.

Finally, in the interpretation of our neuroimaging results and the resulting implications for adolescents’ experiences with peer rejection, some inferences were based on previous research linking specific regions and behavioral functions. The ability to judge with certainty what activation in a particular region means is limited, given the multiple functions that a region may be involved in (Poldrack, 2006); however, this type of inference is inevitable in the early stages of a particular field or methodology, and only continued neuroimaging work on social development will decrease the need to make these ‘reverse inferences’ (Pfeifer et al., in press).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND CONCLUSION

Future research should continue to explore the neural and behavioral correlates of peer rejection during adolescence by making use of multiple age groups, differences in pubertal development, and specific targeted populations. For example, although one recent study examined age differences in neural responses during peer interactions (Guyer, McClure-Tone, Shiffrin, Pine, and Nelson, in press), further examination of neural responses to peer rejection across children, adolescents and adults would increase understanding of how neural responses change across the unique adolescent transition when peer rejection is so salient. Similarly, given previous research indicating that pubertal changes during adolescence are related to many aspects of social development, examining neural responses to rejection within the context of pubertal development would also provide valuable information about how physiological maturation might impact responses to peers across the adolescent transition. In addition, it would be useful for future studies to specifically target adolescents who might provide valuable information about peer rejection experiences, such as chronically rejected or socially anxious individuals (see Guyer et al., 2008). Finally, given that prefrontal cortex immaturity might impact adolescents’ social experiences, concurrent structural and functional neuroimaging analyses would be useful for examining how brain development is related to brain response and function during rejection experiences.

In conclusion, this study provides an initial inquiry into the experience of peer rejection within the adolescent brain. Because fMRI techniques allowed us to examine neural responses as they occurred, we were able to contribute new evidence regarding the underlying processes that might support subjective responses to rejection experiences. Hopefully, with continued work on this topic using novel methodologies and neuroimaging technologies, the fields of adolescent development and peer relations will gain unique perspectives that will inform our understanding of peer rejection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by the Santa Fe Institute Consortium, as well as by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, an Elizabeth Munsterberg Koppitz Award and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award to C. Masten. For generous support the authors also wish to thank the Brain Mapping Medical Research Organization, Brain Mapping Support Foundation, Pierson-Lovelace Foundation, Ahmanson Foundation, Tamkin Foundation, Jennifer Jones-Simon Foundation, Capital Group Companies Charitable Foundation, Robson Family, William M. and Linda R. Dietel Philanthropic Fund at the Northern Piedmont Community Foundation, and Northstar Fund. This project was in part also supported by grants (RR12169, RR13642 and RR00865) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH); its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCR or NIH. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Nathan Fox served as a guest editor for this article. Special thanks to Elliot Berkman for statistical consultation.

REFERENCES

- Abecassis M., Hartup W.W., Haselager G.J.T., Scholte R.H.J., Lieshout C.F.M. Mutual antipathies and their developmental significance. Child Development. 2002;73:1543–1556. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J.P., Porter M.R., McFarland F.C., Marsh P., McElhaney K.B. The two faces of adolescents’ success with peers: Adolescent popularity, social adaptation, and deviant behavior. Child Development. 2005;76:747–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armistead L., Forehand R., Beach S.R.H., Brody G. Predicting interpersonal competence in young adulthood: The roles of family, self and peer systems during adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1995;4:445–460. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine J.R. Circuitry and functional aspects of the insular lobe in primates including humans. Brain Research, Brain Research Reviews. 1996;22:229–244. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(96)00011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayduk O., Mendoza-Denton R., Mischel W., Downey G., Peake P.K., Rodriguez M. Regulating the interpersonal self: Strategic self-regulation for coping with rejection sensitivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:776–792. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz Q., Schnitzler A., Enck P. Functional neuroimaging of visceral sensation. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2000;17:604–612. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S., Khang H., Ham B., Yoon S.J., Jeong D.U., Lyoo I.K. Diminished rostral anterior cingulate activity in response to threat-related events in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2003;42:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B.B. Peer groups and peer cultures. In: Feldman S.S., Elliot G.R., editors. At the Threshold: The Developing Adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 171–196. [Google Scholar]

- Buchel C, Morris JS, Dolan RJ, Friston KJ. Brain systems mediating aversive conditioning: An event-related fMRI study. Neuron. 1998;20:947–957. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D. Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development. 1990;61:1101–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D., Furman W., Wittenberg M.T., Reis H.T. Five domains of interpersonal competence in peer relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:991–1008. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.6.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burklund L.J., Eisenberger N.I., Lieberman M.D. The face of rejection: Rejection sensitivity moderates dorsal anterior cingulate activity to disapproving facial expressions. Social Neuroscience. 2007;2:238–253. doi: 10.1080/17470910701391711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwallader T.W., Cairns R.B. Developmental influences and gang awareness among African-American inner city youth. Social Development. 2002;11:245–265. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns R.B., Cairns B.D. Lifelines and Risks: Pathways of Youth in Our Time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns R.B., Perrin J.E., Cairns B.D. Social structure and social cognition in early adolescence: Affiliative patterns. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1985;5:339–355. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns R.B., Leung M.C., Gest S.D., Cairns B.D. A brief method for assessing social development: Structure, reliability, stability, and developmental validity of the Interpersonal Competence Scale. Behavioral Research Therapy. 1995;33:725–736. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00004-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna A.E., Trimble M.R. The precuneus: A review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain. 2006;129:564–583. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cechetto D.F., Saper C.B. Evidence for a viscerotopic sensory representations in the cortex and thalamus in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neuroscience. 1987;262:27–45. doi: 10.1002/cne.902620104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.H., Ridler K., Suckling J., et al. Brain imaging correlates of depressive symptom severity and predictors of symptom improvement after antidepressant treatment. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Kupersmidt JB. Peer group behavior and social status. . In: Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer rejection in childhood. Cambridge studies in social and emotional development. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M., Larson R. Being Adolescent: Conflict and Growth in the Teenage Years. New York: Basic Books; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Dekovic M., Gerris J.R.M. Developmental analysis of social cognitive and behavioral differences between popular and rejected children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1994;15:367–386. [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein D.P., Leibenluft E. Emotional regulation in children and adolescents: Boundaries between normalcy and bipolar disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:1105–1131. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G., Feldman S.I. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durston S., Casey B.J. What have we learned about cognitive development from neuroimaging? Neuropsychologia. 2005;44:2149–2157. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durston S., Davidson M.C., Tottenham N., et al. A shift from diffuse to focal cortical activity with development. Developmental Science. 2006;9:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger N.L., Lieberman M.D., Williams K.D. Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science. 2003;302:290–292. doi: 10.1126/science.1089134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger N.I., Way B.M., Taylor S.E., Welch W.T., Lieberman M.D. Understanding genetic risk for aggression: Clues from the brain's response to social exclusion. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:1100–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltz E.L., White L.E. Pain “relief” by frontal cingulumotomy. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1962;19:89–100. doi: 10.3171/jns.1962.19.2.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman S.D., Cohen J.D., Fizgerald M., Eddy W.F., Mintun M.A., Noll D.C. Improved assessment of significant activation in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI): Use of a cluster-size threshold. Magnetic Resonance Medicine. 1995;33:636–647. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd J.N., Castellanos F.X., Rajapakse J.C., Vaituzis A.C., Rapoport J.L. Sexual dimorphism of the developing human brain. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 1999;21:1185–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(97)00158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N., Giedd J.N., Lusk L., et al. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2004;101:8174–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini M.L., Pradelli S., Serafini M., et al. Explicit and incidental facial expression processing: An fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2001;14:465–473. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S., Bellmore A., Juvonen J. Peer victimization in middle school: When self and peer views diverge. Journal of Applied School Psychology. 2003;19:117–137. [Google Scholar]

- Grosbras MH, Jansen M, Leonard G, et al. Neural mechanisms of resistance to peer influence in early adolescence. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:8040–8045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1360-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross EF. Logging on, Bouncing Back: An Experimental Investigation of Online Communication Following Social Exclusion. University of California, Los Angeles: (Doctoral dissertation; 2007. Dissertation Abstracts International, 67(9-B), 5442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer A.E., Lau J.Y., McClure-Tone E.B., et al. Amygdala and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex function during anticipated peer evaluation in pediatric social anxiety. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:1303–1312. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.11.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer A.E., McClure-Tone E.B., Shiffrin N.D., Pine D.S., Nelson E.E. Probing the neural correlates of anticipated peer evaluation in adolescence. Child Development. in press doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri A.R., Bookheimer S.Y., Mazziotta J.C. Modulating emotional responses: Effects of a neocortical network on the limbic system. Neuroreport: For Rapid Communication of Neuroscience Research. 2000;11:43–48. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200001170-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoglund W., Lalonde C.E., Leadbeater B. Social-cognitive competence, peer rejection and neglect, and behavioral and emotional problems in middle childhood. Social Development. 2008;17:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs J., Card N.A., Hodges E.V.E. Victimization by peers in the school context. NYS Psychologist. 2001;13:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J., Graham S., Schuster M.A. Bullying among young adolescents: the strong, the weak, and the troubled. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1231–1237. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keedwell P., Drapier R., Surguladze S., Giampietro V., Brammer M., Phillips M. Neural markers of symptomatic improvement during antidepressant therapy in severe depression: subgenual cingulate and visual cortical responses to sad, but not happy, facial stimuli are correlated with changes in symptom score. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2008 doi: 10.1177/0269881108093589. doi:10.1177/0269881108093589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Chey J, Chung A, Bae S, Khang H, Ham B, Yoon SJ, Jeong DU, Lyoo IK. Diminished rostral anterior cingulate activity in response to threat-related events in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2003;42:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kross K.W., Heimdal J.H., Olsnes C., Olofson J., Aarstad H.J. Neural dynamics of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19:945–956. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.6.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane R.D., Reiman E.M., Ahern G.L., Schwartz G.E., Davidson R.J. Neuroanatomical correlates of happiness, sadness, and disgust. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:926–933. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Wiesel R., Nuttman-Shwartz O., Sternberg R. Peer rejection during adolescence: Psychological long-term effects – a brief report. Journal of Loss & Trauma. 2006;11:131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman M. D., Jarcho J. M., Satpute A. B. Evidence-based and intuition-based self-knowledge: An fMRI study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:421–35. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman M. D., Eisenberger N. I., Crockett M. J., Tom S. M., Pfeifer J. H., Way B. M. Putting feelings into words: Affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity to affective stimuli. Psychological Science. 2007;18:421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B., Downey G., Bonica C., Paltin I. Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:481–506. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh R., Zhu H., Wang Z., Skudlarski P., Peterson B.S. A developmental fMRI study of self-regulatory control in Tourette's syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:955–966. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.6.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure S.M., Berns G.S., Montague P.R. Temporal prediction errors in a passive learning task activates human striatum. Neuron. 2003;38:339–346. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson E.E., Leibenluft E., McClure E.B., Pine D.S. The social re-orientation of adolescence: a neuroscience perspective on the process and its relation to psychopathology. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:163–174. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Doherty J.P., Dayan P., Friston K., Critchley H., Dolan R.J. Temporal difference models and reward-related lerning in the human brain. Neuron. 2003;38:329–337. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Doherty J.P., Dayan P., Schultz J., Deichmann R., Friston K., Dolan R.J. Dissociable roles of ventral and dorsal striatum in instrumental conditioning. Science. 2004;304:452–454. doi: 10.1126/science.1094285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst J.T., Hopmeyer A. Sociometric popularity and peer-perceived popularity: Two distinct dimensions of peer status. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1988;18:125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic P., Ingvar M. Imaging cognitive modulation of pain processing. Pain. 2002;95:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00467-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer JH, Masten CL, Borofsky LA, Dapretto M, Lieberman MD, Fuligni AJ. Neural correlates of direct and reflected self-appraisals in adolescents and adults: When social perspective-taking informs self-perception. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan K.L., Wager T., Taylor S.F., Liberzon I. Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: A meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in PET and fMRI. Neuroimage. 2004;16:331–348. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps E.A., Delgado M.R., Nearing K.I., LeDoux J.E. Extinction learning in humans: Role of the amygdala and vmPFC. Neuron. 2004;43:897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M.L., Young A.W., Senior C., Brammer M., Andrew C., Calder A.J., Bullmore E.T., Perret D.I., Rowland D., Williams S., Gray J., David A.S. A specific neural substrate for perceiving facial expressions of disgust. Nature. 1997;389:495–498. doi: 10.1038/39051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M.L., Drevets W.C., Rauch S.L., Lane R. Neurobiology of emotion perception, I: The neural basis of normal emotion perception. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:504–514. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M.L., Williams L.M., Heining M., et al. Differential neural responses to overt and covert presentations of facial expressions of fear and disgust. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1484–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack R.A. Can cognitive processes be inferred from neuroimaging data? Trends in Cognitive Science. 2006;10:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein M.J., Sheah C.S., Guyer A.E. Peer victimization, cue interpretation, and internalizing symptoms: Preliminary concurrent and longitudinal findings for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:11–24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainville P., Duncan G.H., Price D.D., Carrier B., Bushnell M.C. Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulated but not somatosensory cortex. Science. 1997;277:968–971. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A., Stegge H., Terwogt M.M., Kamphuis J.H., Telch M.J. Children's coping with in vivo rejection: An experimental investigation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:877–889. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A., Stegge H., Terwogt M.M. Children's coping with peer rejection: The role of depressive symptoms, social competence, and gender. Infant and Child Development. 2006;15:89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby K. Effects of peer victimization in schools and perceived social support on adolescent well-being. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23:57–60. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby K. Consequences of bullying in schools. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;48:583–590. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez P.F., Aron A.R., Poldrack R.A. Ventral-striatal/nucleus-accumbens sensitivity to prediction errors during classification learning. Human Brain Mapping. 2006;27:306–313. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin K.H., Daniels-Beirness T., Hayvren M. Social and social-cognitive correlates of sociometric status in preschool and kindergarten children. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 1982;14:338–349. [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom M.J., Cillessen A.H.N., Eisenhower A. Children's appraisal of peer rejection experiences: Impact on social and emotional adjustment. Social Development. 2003;12:530–550. [Google Scholar]

- Sawamoto N., Honda M., Okada T., et al. Expectation of pain enhances responses to nonpainful somatosensory stimulation in the anterior cingulate cortex and parietal operculum/posterior insula: An event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:7438–7445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07438.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Neural coding of basic reward terms of animal learning theory, game theory, microeconomics and behavioural ecology. Current Opinions in Neurobiology. 2004;14:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharot T., Riccardi A.M., Raio C.M., Phelps E.A. Neural mechanisms mediating optimism bias. Nature. 2007;450:102–105. doi: 10.1038/nature06280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter V., Dennis M., Pritchard M. Theory of mind and peer acceptance in preschoolers. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002;20:545–564. [Google Scholar]