Abstract

Some mutations resulting in protein sequence change might be tightly related to certain human diseases by affecting its roles, such as sickle cell anemia. Until now several databases, such as PMD, OMIM and HGMD, have been developed, providing useful information about human disease-related mutation. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS) has been used for characterizing proteins in various conditions; however, there is no system in place for finding disease-related mutated proteins within the MS results. Here, a Systematical Platform for Identifying Mutated Proteins (SysPIMP; http://pimp.starflr.info/) was developed to efficiently identify human disease-related mutated proteins within MS results. SysPIMP comprises of three layers: (i) a standardized data warehouse, (ii) a pipeline layer for maintaining human disease databases and X!Tandem and BLAST and (iii) a web-based interface. From OMIM AV part, PMD and SwissProt databases, 35 497 non-redundant human disease-related mutated sequences were collected with disease information described by OMIM terms. With the interfaces to browse sequences archived in SysPIMP, X!Tandem, an open source database-search engine used to identify proteins within MS data, was integrated into SysPIMP to help support the detection of potential human disease-related mutants in MS results. In addition, together with non-redundant disease-related mutated sequences, original non-mutated sequences are also provided in SysPIMP for comparative research. Based on this system, SysPIMP will be the platform for efficiently and intensively studying human diseases caused by mutation.

INTRODUCTION

In biological fields, mutation has been defined as changes in the nucleotide sequences, which can cause phenotype changes, such as the different colors of butterflies which can affect the survival rate against predators. When mutations occur in humans, they can influence individual survival rates by changing their activities, interaction ability and/or regulation of specific proteins at various levels (1–3). In particular, mutations resulting in amino acid sequence changes directly increase and/or decrease the functionality of proteins through conformational changes, which can cause certain human diseases (2–5). These mutations can be inherited through the generations, presenting the importance of disease control. For example, sickle-cell anemia is caused by a point mutation at sixth codon (G6V) in the hemoglobin beta gene (HBB) that changes the protein sequence and diminishes the ability to carry oxygen (6). Phenylketonuria (PKU), which is found in newborn babies, is triggered by the defective phenylalanine hydroxylase enzyme (PAH). This disease is known to be inherited in a recessive manner (7). Due to their critical effects on humans, protein mutations associated with human diseases have been studied broadly and in detail for a long time (8).

The collection of mutated sequences that cause single gene disorders started when the exact position of globin gene mutation was revealed (9). With the help of advanced molecular and medical biology, as well as DNA sequencing technologies (10), a large number of mutated sequences that cause diseases in humans have been revealed, triggering the construction of several general and/or central relational databases for human mutations related to disease. These kinds of centralized databases were classified as General Mutation Databases (GMDB) (11). One of them is the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, (OMIM; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=omim) which provides 19 738 OMIM terms detailing a number of human diseases with 16 336 Allelic Variants (AV) records, of which most describe disease-producing mutations (12–14) (as of 02-August-2008). The OMIM AV field only contains gene names, mutation information and some related descriptions organized by experts in text format; however, mutated protein sequences are not available. The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD; http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php; as of June 22, 2008) has archived 57 294 mutations in a academic version and 79 098 mutations in HGMD Professional as a commercial version that contains the largest number of human gene mutations (15). Although the academic version of HGMD provides cDNA sequences for each normal gene in public, it does not provide mutated amino acid sequences. One interesting thing is that the contents of the two largest datasets, OMIM and HGMD, do not overlap, i.e., 1647 of 2263 genes (72.78%) having mutation causing disease from two databases were shared, and 143 and 473 genes with mutation data were not present in HGMD and OMIM, respectively (11). In addition, the number of mutations in each gene is also largely different; only 450 genes (19.89%) show the same number of mutations (11), indicating that the total number of human disease-related mutated sequences characterized until now should be larger than the mutated sequences in each database. As another resource, SwissProt also serves 38 022 polymorphisms (only for point mutations) occurred in human genes, of which some have disease information described with OMIM terms (16).

On the other hand, the locus-specific databases (LSDBs), another type of mutation database, started being constructed after the revelation of globin mutations (17). LSDBs have high quality information on the gene itself and its mutations (11) and 672 LSDBs listed in the Human Genome Structural Variation Project web site (http://www.hgvs.org/dblist/glsdb.html; as of March 9, 2007) are available now (18). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in humans are another resource for disease-associated mutations and many databases have been developed for revealing the effects of SNPs on protein functionalities and human diseases (8,19–26).

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique for characterizing the chemical composition of a sample based on the mass-to-charge ratio of charged material. Tandem mass spectrometry, known as MS/MS, has been used as a high-throughput method to identify amino acids of fragmented proteins digested by trypsin typically (27). MS technique has been used not only to identify proteomes but also to identify several modifications of proteins, such as post-translational modification (PTM) (28). As a consequence, 2695 MS/MS results have been accumulated in Proteinpedia (http://www.humanproteinpedia.org/) (29,30). Besides PTM, protein mutations can also be identified from the MS/MS results because they have slightly different amino acids compared to the normal proteins, which can make MS peaks shift (31). For identifying these various forms of proteins, several widely used database-search software programs, such as SEQUEST (http://fields.scripps.edu/sequest/), Mascot (32) and X!Tandem (33), which interpret MS peaks and match them to the set of sequences with their own algorithms, have been developed. To detect disease-associated mutations in human proteins by these programs, specialized datasets are required. However, to date, there are no proper datasets optimized for identifying human disease-related mutated proteins based on MS technology. MSIPI, which was modified based on the International Protein Index (IPI), was developed to identify human mutated sequences. MSIPI retained its relatively compact nature while maximizing the chance of identifying sequence variants (19), which contain mutated sequence information but do not provide any disease information.

To surmount these deficiencies in studying human mutated proteins, we developed a web-based system to identify human disease-related mutated sequences from MS results. Termed, the Systematic Platform for Identifying Mutated Protein (SysPIMP; http://pimp.starflr.info/), SysPIMP embraces Protein Mutated Database (PMD; http://pmd.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) (34), OMIM AV mutation information (13) and human polymorphisms and disease mutations from SwissProt (16) with seven different sources of human normal proteins. In total, SysPIMP collected 35 497 non-redundant human disease-related mutated proteins of which 21 513 were from OMIM, 7261 from PMD and 15 308 from SwissProt. To handle disease information uniformly, SysPIMP is based on the framework of OMIM integrating mutation information dispersed in other public databases and it maps all disease-related mutated proteins to certain OMIM terms. Based on these criteria, SysPIMP provides more comprehensive and integrative datasets that users can access freely. To demonstrate the possibility that our non-redundant mutated sequences can be a new dataset used for identifying human disease-related mutated proteins from MS results by X!Tandem, an open source tool for identifying proteins from tandem MS spectra with new algorithm (33), was integrated into the SysPIMP with newly developed interfaces to present human disease-related proteins. In addition, the web-based BLAST tool was also integrated into our system to meet specialized requirements.

SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE

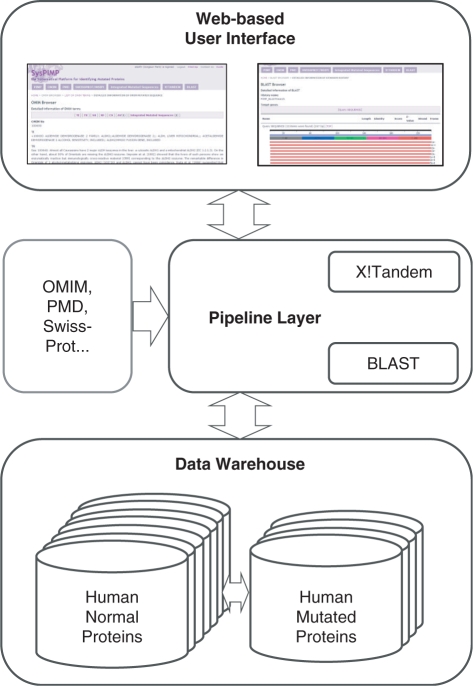

For managing complicated human gene resources (i.e. four different versions of human genomes) and already developed bioinformatics programs, such as BLAST and X!Tandem, SysPIMP was designed and constructed as three layers: (i) the data warehouse layer which aims to manage and process sequences collected from different sources, (ii) the pipeline layer which undertakes the renewal of information, such as the daily update of OMIM, not only to recover mutated sequences based on collective human normal proteins, but also to maintain various datasets for X!Tandem and BLAST and (iii) web-based user interfaces both for accessing the databases and for presenting the results of two Linux-executable bioinformatics programs: X!Tandem and BLAST (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The system architecture of SysPIMP. The overall system structure of SysPIMP is comprised of three layers. Data warehouse embraces human normal proteins collected from seven different sources and human mutated proteins derived from four different sources, presented as database diagram in the lower part. Pipeline layer plays a role in updating external databases, such as OMIM, PMD and SwissProt and for bridging between external programs, such as X!Tandem and BLAST programs, and users. Web interface provides the gateway for users not only to access all database contents but also to present X!Tandem and BLAST results as various formats on the web.

In the data warehouse layer, the standardized database structure, which was developed in Comparative Fungal Genomics Platform (CFGP; http://cfgp.snu.ac.kr/) (35) and which has been stabilized through several databases (36–40), was implemented for dealing with differently originated sequences: PMD, OMIM, SwissProt, MSIPI and four different versions of human genomes (Ensembl release 48, NCBI Celera assembly, NCBI HuRef assembly and NCBI reference genome version 36.3) (13,16,34,41–44) having diverse additional information. With this structure, heterogeneous sequences can be entered into two bioinformatics tools and those results manipulated in the same way.

The pipeline layer in SysPIMP plays six obvious roles: (i) updating the contents of OMIM for following a daily-updated OMIM database, (ii) collecting and removing redundancy of human normal proteins (Integrated annotated Human normal Proteins or IHPs) from seven sources, (iii) based on IHPs, generating mutated sequences from gene name and position in OMIM AV field, (iv) integrating and updating disease-related mutated sequences of human from three different sources: PMD, OMIM and SwissProt Human polymorphisms and disease mutations, (v) bridging between user requests via a web interface and two programs, such as X!Tandem and BLAST and (vi) maintaining X!Tandem and BLAST datasets with the latest sequences. The components belonging to this pipeline were developed using Java and PERL. All processes of the pipeline keep old primary keys for maintaining already existed data, enabling users to track back their own data in the SysPIMP web site.

The web interface was designed to provide an efficient way to search the complex data deposited in SysPIMP. For example, IHPs derived from seven different sources can be traced back to the original sequences with presenting its related information, and they are also linked to mutated sequences with disease information described as OMIM terms. In the interface for X!Tandem, the analysis results will be stored in the database under the X!Tandem history browser. In the case of BLAST search, a graphical interface will be provided for each result. In addition, the SNU Genome Browser (http://genomebrowser.snu.ac.kr/; Jung et al., under revision) was implemented to present human genome contexts around human disease-related genes for further studies.

DATASET OF HUMAN DISEASE-RELATED MUTATED PROTEINS

For providing comprehensive dataset of human disease-related mutated sequences, mutated sequences deposited in PMD, OMIM and SwissProt Human polymorphisms and disease information described in OMIM terms were used. Because they were stored in different formats, the programs for dealing with each source were developed independently for integrating them into the standardized structure.

Mapping PMD disease information to OMIM terms

PMD (http://pmd.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) had been updated until 2007, providing plentiful disease-related mutated sequences from many organisms including humans (34). The latest version of PMD (March 26, 2007) serves 218 873 mutated sequences from 45 239 entries in many species, containing the disease information as text description. Only 2805 (15.85%) entries out of 17 702 human entries have disease information. Nine hundred and sixty-four different disease names out of 2805 entries were mapped to 967 OMIM terms after correcting typos in the disease name field. Finally, a non-redundant 7261 out of 9808 mutated sequences that have disease information described as OMIM term were registered in SysPIMP.

Reviving mutated sequences from OMIM Allelic Variants field based on integrated annotated normal human proteins from seven different sources

OMIM Allelic Variants (AV) field provides gene names, mutation information, and disease descriptions organized by experts, without mutated sequences. The OMIM has been managed as a text-based database, so that the data cannot be directly used for constructing relational databases even though it contains highly organized information. Not all the gene names used in the OMIM AV field were matched to the gene names used in other human gene databases, such as SwissProt (16), for finding original amino acid sequences. Moreover, original and changed amino acid sequences at mutated position described in AV field were not matched to rescued sequences from other human protein sources, hampering our recovery of mutated sequences. To overcome these problems, the largest set of gene names with amino acid sequences as well as corrected positions of mutation is required.

Based on seven separate sources of human proteins, such as four different versions of human genomes (Ensembl release 48, NCBI Celera assembly, NCBI HuRef assembly, and NCBI human reference genome), and normal protein sequences in PMD, SwissProt, and MSIPI, 99 410 non-redundant human proteins designated as Integrated annotated Human normal Proteins (IHPs) were collected with 73 132 distinct gene names. Because IHPs were collected based only on amino acid sequences, IHPs contain possible isoforms of certain genes from seven different sources with the result that the number of IHPs is larger than the number of distinct gene names. Especially for the collection of gene names, two additional resources were used: genemap data in OMIM database and OMIM Mutation Search constructed by Dr Anderw C.R. Martin's Group (http://www.bioinf.org.uk/omim/). The resources helped us to correct mutation positions in OMIM.

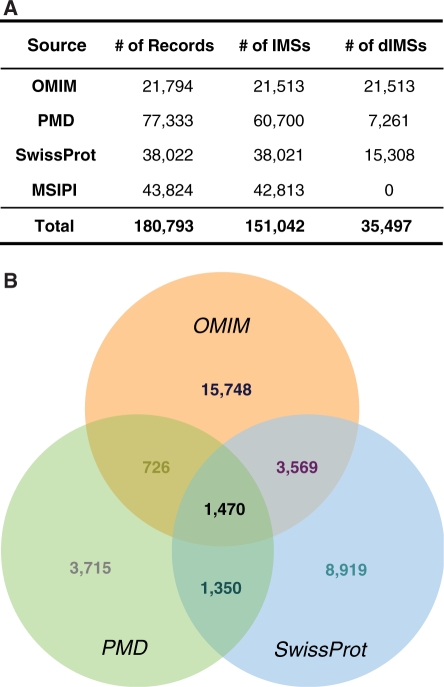

Eleven different regular expressions for extracting mutation types and positions from the OMIM AV field were established. Due to the limited information, such as the exon/intron structure and nucleotide sequences of each gene, not all the point mutations including termination, insertion, deletion and duplication were considered. Based on IHPs and mutation information, the pipeline for rescuing disease-related mutated sequences described in AV field was developed as two steps. In the first step, gene names and mutated positions described in AV field were compared with IHPs containing the largest set of human gene names. For solving the incorrect positions not matched in the first step, the data downloaded from OMIM Mutation Search (http://www.bioinf.org.uk/omim/) were used. The unmatched AV records in the first step were compared with the corrected mutated positions in the OMIM Mutation Search as a second step. Taken together, a non-redundant 21 513 out of 21 794 human disease-related mutated sequences from 16 336 OMIM AV records were recovered and subsequently merged into the Integrated Human Mutated Sequences (IMSs) while removing the redundancy at the amino acids level (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

The number of non-redundant human mutated proteins (IMSs) in SysPIMP originated from OMIM, PMD and SwissProt. (A) The table presents the total number of records, IMS and disease-related IMSs (dIMS) in each source. (B) Three different color-coded circles present the sources of human dIMSs: Orange is OMIM, green is PMD and blue is SwissProt Human Polymorphisms and Disease Mutations. Each number on the venn-diagram indicates the absolute number of sequences.

Integrating SwissProt Human polymorphisms and disease mutations and MSIPI sequences into SysPIMP

SwissProt Human polymorphisms and disease mutations database deals with only point mutations of human genes based on SwissProt protein database (16). In the current release (Release 55.0 of February 26, 2008), 15 964 (41.25%) out of 38 022 human polymorphisms have disease information depicted with OMIM terms. MSIPI, developed for the optimized dataset of MS data analysis from IPI (41), contains 44 020 mutated sequences from 70 444 normal sequences. All mutated sequences of both databases were also merged into IMSs in SysPIMP (Figure 2A).

Comprehensive dataset of human disease-related mutated proteins

From four sources of human mutated sequences (PMD, OMIM AV field, SwissProt and MSIPI), in total, 35 497 (23.57%) out of 151 042 non-redundant mutated sequences have disease information described as OMIM terms (Figure 2A). Due to the overlap between different sources, the origin of 35 497 disease-related non-redundant sequences is presented as a Venn-diagram (Figure 2B). In the diagram, MSIPI originated sequences are excluded because they do not have any disease information. The 1470 disease-related mutated sequences from all three origins are occupied in 4.14% of all disease-related IMSs, and only 7115 proteins (20.04%) come from at least two different sources, presenting that three sources have collected different disease-related mutated sequences studied till now.

Disease classification of IMSs

For classifying human diseases of IMS, the classification system of Human Disease Network (45) was used. The classification system was constructed based on OMIM terms mentioned in Morbid Map, which is the most complete and best organized list of known disorder-gene associations (46), covering 1781 (9.02%) out of 19 738 OMIM terms. Even though OMIM terms in the Morbid Map do not cover almost all OMIM terms, around 40% OMIM terms in IMSs can be classified via that classification well, presenting Morbid map can be used for classifying disease reasonably. There are 3508 different OMIM terms assigned to 35 497 IMSs, among which 1493 (42.56%) terms belong to Morbid Map. Out of 35 497 IMSs, 23 034 (64.89%) are classified by OMIM terms belonging to Morbid Map, showing that the ratio of the IMSs classified by the disease classification is larger than the proportion of OMIM terms. Interestingly, 4323 (81.55%) out of the 5301 IHPs which contain one or more IMSs are assigned to the 23 034 IMSs. It shows the usability of Human Disease Network by demonstrating that more than 80% of disease related genes can be classified by the disease classification of Human Disease Network (45). Based on this approach for disease classification, the detailed analyses will uncover the feature of human diseases caused by mutation.

WEB-BASED DATASET BROWSERS OF SysPIMP

Because of diverse sources in SysPIMP, many browsers which allow users to explore different types of data on the web easily were implemented. Each browser provides not only origin-specific information with sequences but also the related information with IHPs and IMSs.

OMIM Browser

OMIM Browser provides the main contents of OMIM database and mutated sequences originated from OMIM AV field via the pipeline. Related information is linked to each other in detailed pages. In addition, OMIM classification used in this study (45) and detailed list of IHPs and IMSs are presented.

PMD Browser

In SysPIMP, text-based PMD was processed and reformulated to the relational database for human sequences. Two thousand, eight hundred and five entries filtered with the criteria of human disease-related mutations with normal and mutated sequences are presented. Curated disease names in PMD with OMIM terms are also provided via PMD Browser.

SwissProt/MSIPI Browser

SwissProt Browser provides normal sequences (including isoforms) and mutated sequences with disease information, supporting the search function for finding certain SwissProt sequences by accession number and gene name. Currently SwissProt Browser contains 30 413 human normal proteins and 38 022 polymorphisms. Sequences from MSIPI, developed as an efficient way to identify sequence variants in MS results (41), were split into original and mutated sequences because sequences of MSIPI were the concatenated form of several amino acid sequences. MSIPI Browser serves 70 444 entries with 44 020 mutated sequences.

Human Genome Browser

Human Genome Browser contains four versions of human genomes: Ensembl release 48, NCBI Celera assembly, NCBI HuRef assembly, and NCBI human reference genome version 36.3 (42–44). It provides the summary of genome status, the list and detailed information of 128 883 ORFs on totally 11 646 contigs with exon structures. A Chromosomal diagram was constructed based on Ensembl release 48. With graphical representation of human genome contexts, mutated positions of human proteins in SysPIMP are presented via SNU Genome Browser (http://genomebrowser.snu.ac.kr/; Jung et al., under revision).

WEB INTERFACE FOR ANALZYING MASS SPECTROSCOPY RESULTS USING X!TANDEM

For identifying mutated sequences from MS results, we developed a specialized web-based interface and datasets for X!Tandem based on 35 497 Integrated human disease-related mutated sequences (IMSs). SysPIMP provides nine different datasets: five normal sequence sets from human genomes and SwissProt, two mutated sequence sets from PMD and MSIPI, and two integrated datasets (IHP and disease-related IMSs).

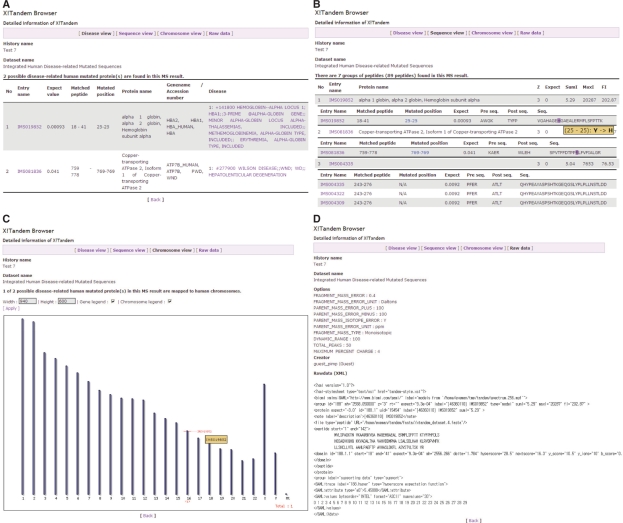

The interface for inputting parameters of X!Tandem was designed based on the web site managed by thegpm group (http://human.thegpm.org/tandem/thegpm_tandem_a.html). In the result pages, four different views are available to users: (i) Disease view, (ii) Sequence view, (iii) Chromosome view and (iv) Raw Data view. Disease view displays the list of possible human disease-related mutated sequences from uploaded MS data with disease information (Figure 3A). The criteria for filtering them consist of two steps: (i) finding mutated sequences which have disease information in the X!Tandem results and (ii) checking whether the matched region contains mutated amino acids or not. Sequence view was designed for showing all results of X!Tandem because some users want to know all matched proteins with detailed information (Figure 3B). Chromosome view draws the map of human chromosomes based on Ensembl release 48 with red bars of disease-related mutated proteins. It provides the physical position of disease-related mutated genes as an interactive diagram, with the link to the detailed information of mutated proteins (Figure 3C). Raw Data view shows the detailed options of X!Tandem and XML file generated by X!Tandem as a result (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Specialized web interface of X!Tandem for identifying disease-related mutated proteins from mass spectrometry results. SysPIMP provides four different views of X!Tandem results. (A) Disease view presents the list of identified proteins which are linked to disease-related mutated sequences from MS results. Detected position from X!Tandem and mutated position are displayed in one line. (B) Sequence view shows the whole list of identified proteins of MS results. (C) Chromosome view draws the chromosomal map with human disease-related proteins identified from MS result, which have chromosomal positional information. If the label is clicked by a user, detailed information of IMS will appear. (D) Raw Data view prints XML file generated by X!Tandem.

All X!Tandem results will be stored in the SysPIMP along with the user's information, so that the user can browse the X!Tandem results executed previously without running the program again.

MAINTAINENCE AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

To update disease information, the OMIM database will be downloaded and applied to the SysPIMP database monthly. Based on the latest information, the pipeline for maintaining the mutated sequences from OMIM will update the database as well. The PMD, SwissProt Human polymorphisms and disease mutations, MSIPI and human genomes will be monitored and periodically updated as will the pipeline and all related information.

SysPIMP is the integrated platform not only for collecting human disease-related mutated sequences but also for providing the programs to identify mutated proteins from the mass spectrometry results. For expanding the data warehouse for disease-related mutated sequences in humans with accurate disease information, diverse locus-specific disease related databases (LSDB) (18), such as IDBases (47) and SNP-related databases, such as dbSNP (48), can be integrated. Using the standardized form for integrating external programs, other programs for analyzing MS result data, such as Mascot (32), can be incorporated in SysPIMP to enhance the ability to identify disease-related proteins.

FUNDING

National High-Tech R&D Program (863) (2006AA02Z334); National Basic Research Program of China (2006CB910700, 2004CB720103, 2004CB518606, 2003CB715901); Key Research Program [(CAS) KSCX2-YW-R-112]; Crop Functional Genomics Center (CG1141, to Y.H.L.); Biogreen21 Project funded by Rural Development Administration (20080401034044, to Y.H.L.) Funding for open access charge: National High-Tech R&D Program of China(863) (2006AA02Z334).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Dr Chuan Wang for maintaining the database server. We also thank Kyongyong Jung for making the SysPIMP web site clean and clear.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kleinjan DJ, van Heyningen V. Position effect in human genetic disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:1611–1618. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.10.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrer-Costa C, Orozco M, de la Cruz X. Characterization of disease-associated single amino acid polymorphisms in terms of sequence and structure properties. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;315:771–786. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z, Moult J. SNPs, protein structure, and disease. Hum. Mutat. 2001;17:263–270. doi: 10.1002/humu.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sunyaev S, Ramensky V, Bork P. Towards a structural basis of human non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms. Trends Genet. 2000;16:198–200. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)01988-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chasman D, Adams RM. Predicting the functional consequences of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms: structure-based assessment of amino acid variation. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;307:683–706. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingram VM. Chemistry of the abnormal human haemoglobins. Br. Med. Bull. 1959;15:27–32. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a069709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufman S. Phenylketonuria: Biochemical Mechanisms. New York: Plenum Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kono H, Yuasa T, Nishiue S, Yura K. coliSNP database server mapping nsSNPs on protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D409–D413. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baglioni C. The fusion of two peptide chains in hemoglobin Lepore and its interpretation as a genetic deletion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1962;48:1880–1886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.11.1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellegren H. Sequencing goes 454 and takes large-scale genomics into the wild. Mol. Ecol. 2008;17:1629–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George RA, Smith TD, Callaghan S, Hardman L, Pierides C, Horaitis O, Wouters MA, Cotton RG. General mutation databases: analysis and review. J. Med. Genet. 2008;45:65–70. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.052639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyadjiev SA, Jabs EW. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) as a knowledgebase for human developmental disorders. Clin. Genet. 2000;57:253–266. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2000.570403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger J, Bocchini C, Valle D, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledge base of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:52–55. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger J, Valle D, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) Hum. Mutat. 2000;15:57–61. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<57::AID-HUMU12>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stenson PD, Ball EV, Mort M, Phillips AD, Shiel JA, Thomas NS, Abeysinghe S, Krawczak M, Cooper DN. Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD): 2003 update. Hum. Mutat. 2003;21:577–581. doi: 10.1002/humu.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yip YL, Famiglietti M, Gos A, Duek PD, David FP, Gateau A, Bairoch A. Annotating single amino acid polymorphisms in the UniProt/Swiss-Prot knowledgebase. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:361–366. doi: 10.1002/humu.20671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardison RC, Chui DH, Riemer CR, Miller W, Carver MF, Molchanova TP, Efremov GD, Huisman TH. Access to a syllabus of human hemoglobin variants (1996) via the World Wide Web. Hemoglobin. 1998;22:113–127. doi: 10.3109/03630269809092136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horaitis O, Talbot C.C, Jr, Phommarinh M, Phillips KM, Cotton RG. A database of locus-specific databases. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:425. doi: 10.1038/ng0407-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavallo A, Martin AC. Mapping SNPs to protein sequence and structure data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1443–1450. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karchin R, Diekhans M, Kelly L, Thomas DJ, Pieper U, Eswar N, Haussler D, Sali A. LS-SNP: large-scale annotation of coding non-synonymous SNPs based on multiple information sources. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2814–2820. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mooney SD, Altman RB. MutDB: annotating human variation with functionally relevant data. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1858–1860. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dantzer J, Moad C, Heiland R, Mooney S. MutDB services: interactive structural analysis of mutation data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W311–W314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yue P, Melamud E, Moult J. SNPs3D: candidate gene and SNP selection for association studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reumers J, Schymkowitz J, Ferkinghoff-Borg J, Stricher F, Serrano L, Rousseau F. SNPeffect: a database mapping molecular phenotypic effects of human non-synonymous coding SNPs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D527–D532. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stitziel NO, Binkowski TA, Tseng YY, Kasif S, Liang J. topoSNP: a topographic database of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms with and without known disease association. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D520–D522. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jegga AG, Gowrisankar S, Chen J, Aronow BJ. PolyDoms: a whole genome database for the identification of non-synonymous coding SNPs with the potential to impact disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D700–D706. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunt DF, Yates J.R, 3rd, Shabanowitz J, Winston S, Hauer CR. Protein sequencing by tandem mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:6233–6237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature. 2003;422:198–207. doi: 10.1038/nature01511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathivanan S, Ahmed M, Ahn NG, Alexandre H, Amanchy R, Andrews PC, Bader JS, Balgley BM, Bantscheff M, Bennett KL, et al. Human Proteinpedia enables sharing of human protein data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:164–167. doi: 10.1038/nbt0208-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathivanan S, Pandey A. Human proteinpedia as a resource for clinical proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2038–2047. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R800008-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rappsilber J, Mann M. What does it mean to identify a protein in proteomics? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002;27:74–78. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig R, Beavis RC. TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1466–1467. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawabata T, Ota M, Nishikawa K. The Protein Mutant Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:355–357. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park J, Park B, Jung K, Jang S, Yu K, Choi J, Kong S, Park J, Kim S, Kim H, et al. CFGP: a web-based, comparative fungal genomics platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D562–D571. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi J, Park J, Jeon J, Chi MH, Goh J, Yoo SY, Park J, Jung K, Kim H, Park SY, et al. Genome-wide analysis of T-DNA integration into the chromosomes of Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;66:371–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05918.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeon J, Park SY, Chi MH, Choi J, Park J, Rho HS, Kim S, Goh J, Yoo S, Choi J, et al. Genome-wide functional analysis of pathogenicity genes in the rice blast fungus. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:561–565. doi: 10.1038/ng2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park J, Park B, Veeraraghavan N, Jung K, Lee YH, Blair J, Geiser DM, Isard S, Mansfield MA, Nikolaeva E, et al. Phytophthora Database: a forensic database supporting the identification and monitoring of phytophthora. Plant Dis. 2008;92:966–972. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-92-6-0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park J, Park J, Jang S, Kim S, Kong S, Choi J, Ahn K, Kim J, Lee S, Kim S, et al. FTFD: an informatics pipeline supporting phylogenomic analysis of fungal transcription factors. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1024–1025. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park J, Lee S, Choi J, Ahn K, Park B, Park J, Kang S, Lee YH. Fungal Cytochrome P450 Database. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:402. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schandorff S, Olsen JV, Bunkenborg J, Blagoev B, Zhang Y, Andersen JS, Mann M. A mass spectrometry-friendly database for cSNP identification. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:465–466. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0607-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flicek P, Aken BL, Beal K, Ballester B, Caccamo M, Chen Y, Clarke L, Coates G, Cunningham F, Cutts T, et al. Ensembl 2008. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D707–D714. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, Smith HO, Yandell M, Evans CA, Holt RA, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goh KI, Cusick ME, Valle D, Childs B, Vidal M, Barabasi AL. The human disease network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8685–8690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701361104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D514–D517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piirila H, Valiaho J, Vihinen M. Immunodeficiency mutation databases (IDbases) Hum. Mutat. 2006;27:1200–1208. doi: 10.1002/humu.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wheeler DL, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, DiCuccio M, Edgar R, Federhen S, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D5–D12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]