Abstract

The Pathway Interaction Database (PID, http://pid.nci.nih.gov) is a freely available collection of curated and peer-reviewed pathways composed of human molecular signaling and regulatory events and key cellular processes. Created in a collaboration between the US National Cancer Institute and Nature Publishing Group, the database serves as a research tool for the cancer research community and others interested in cellular pathways, such as neuroscientists, developmental biologists and immunologists. PID offers a range of search features to facilitate pathway exploration. Users can browse the predefined set of pathways or create interaction network maps centered on a single molecule or cellular process of interest. In addition, the batch query tool allows users to upload long list(s) of molecules, such as those derived from microarray experiments, and either overlay these molecules onto predefined pathways or visualize the complete molecular connectivity map. Users can also download molecule lists, citation lists and complete database content in extensible markup language (XML) and Biological Pathways Exchange (BioPAX) Level 2 format. The database is updated with new pathway content every month and supplemented by specially commissioned articles on the practical uses of other relevant online tools.

INTRODUCTION

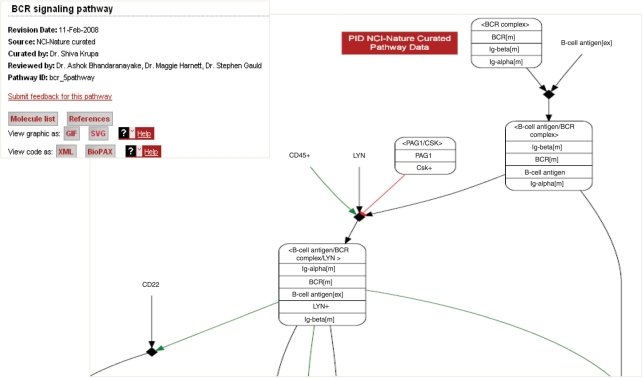

The Pathway Interaction Database (PID, http://pid.nci.nih.gov) is a growing collection of human signaling and regulatory pathways curated from peer-reviewed literature and stored in a computable format. PID was designed to deal with two issues affecting the representation of biological processes: the arbitrariness of pathway boundaries and the need to capture knowledge at different levels of detail. Pathway boundaries are often arbitrary and overlapping: different biologists might include different biochemical interactions in, for example, ‘the p53 signaling pathway’; and it is not unusual for two pathways representing distinct processes to have one or more interactions in common. This fuzziness simply reflects the fact that terms like ‘the p53 signaling pathway’ and ‘the BCR signaling pathway’ are high-level concepts of convenience, designating slices through the very complex mix of concurrent processes in the cell. An important goal of PID is to provide an operational definition of high-level concepts like ‘the BCR signaling pathway’ (Figure 1) in the form of predefined pathways, while at the same time allowing a user to explore novel networks composed computationally from the universe of interactions underlying the predefined pathways. Current knowledge of the components of any given biological process is uneven. For example, for some protein interactants the precise posttranslational modifications might be known, while for other interactants perhaps the only sure knowledge is that the protein is ‘active’. PID provides descriptive mechanisms to cover both of these cases. The ability to represent information at different levels of detail is also useful in communicating generalizations. For example, it is sometimes useful to encapsulate a complex process, such as cytoskeleton reorganization as a single event or to treat as a single entity a set of proteins, such as Class 1A PI3Ks that are functionally equivalent in catalyzing a given event. PID has mechanisms for dealing with incomplete knowledge, for encapsulating complex events and for expressing generalizations.

Figure 1.

BCR signaling pathway. The pathway header information includes the date of the latest revision; the data curation or import source; the curator; the reviewers; the stable pathway identifier; links to a pathway-specific molecule list and a pathway-specific references list; and links to pathway graphic and text data exchange format options.

PID has adopted a network-level representation, similar to Reactome (1), HumanCyc (2) and KEGG (3). Like Reactome and HumanCyc, PID annotates interactions with citations to the literature. PID differs from Reactome, HumanCyc and KEGG in its focus on signaling and regulatory pathways; it does not attempt to cover metabolic processes or generic mechanisms like transcription and translation (see Table 1 for a comparison of PID with other publicly accessible pathway databases). PID contains only structured data and it links to but does not reproduce molecular information readily available from other sources, such as nucleotide or amino acid sequence, molecular weight and chemical formula. The principal source of data in PID is the highly curated ‘NCI-Nature Curated’ collection of pathways, but PID also includes two other sources of data: data imported into the PID data model from Reactome's Biological Pathways Exchange (BioPAX) Level 2 (4) export, and an import of information from the BioCarta collection of pathways (Table 2). All data in PID is freely available, without restriction on use. Bulk downloads are available in BioPAX Level 2, a standard format for exchanging pathway information, and a PID-specific XML format at http://pid.nci.nih.gov/PID/download.shtml.

Table 1.

Open access human pathway databases

| BioCartaa | HumanCycb | KEGGc | Pantherd | PID | Reactomee | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope of content | Metabolic and signaling pathways | Metabolic pathways | Metabolic, regulatory, signaling, disease and drug pathways | Metabolic and regulatory pathways | Signaling and regulatory pathways | Metabolic, signaling and regulatory pathways |

| Human pathways | 353 | 226 | 208 | 165 | 77 | 63 |

| Human events | >3000 | 1493 | 5083 | ∼1500 | 4373 | 2806 |

| Curation | ||||||

| Type | Manual | Part manual/part computational | Manual | Manual | Manual | Manual |

| Expert review | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Literature reference annotation | For pathways | For pathways | For pathways | Optional | For each event | For each event |

| Capture of evidence types | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Data visualization | Non interactive predefined pathways | Interactive predefined pathways | Interactive predefined pathways | Noninteractive predefined pathways | Interactive predefined pathways and dynamically generated interactive network maps | Interactive predefined pathways |

aData from http://www.biocarta.com/ (as of September, 2008).

bData from http://humancyc.org/ (as of September, 2008).

cData from http://www.genome.jp/kegg/xml/hsa/index.html (as of September, 2008).

dData from Nucleic Acids Research 2007, 35(Database issue):D247–D252.

eData from http://www.reactome.org/ (as of September, 2008).

Table 2.

Summary of all data sources

| NCI-Nature Curated | Reactome imported | BioCarta imported | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathways | 77 | 63 | 254 |

| Subpathways | 42 | 753 | 0 |

| Interactions | 4373 | 3466 | 3003 |

| Proteins | 2607 | 2692 | 4218 |

| Small molecules | 135 | 617 | 205 |

| Complexes | 1949 | 1897 | 880 |

DATA MODEL

In PID, an interaction is an event with its participating molecules and conditions. A PID pathway is a network of these events connected by the participant molecules. PID recognizes four kinds of molecules: small molecules (called compounds), RNA, proteins and complexes. PID recognizes five kinds of events: gene regulation (called transcription, but encompassing both transcription and translation), molecule transport (called translocation), small-molecule conversion (called reaction), protein–protein interactions (called modification) and black-box processes whose internal composition is not provided (called macroprocesses). In addition, an entire pathway can be abstracted and used as a single event in another pathway. As a participant in an event, a molecule may have one of four roles: input, output, positive regulator and negative regulator. These roles define simple relations: an interaction consumes its inputs (but not its regulators) and produces its outputs; and the inputs, positive regulators and the absence of negative regulators are jointly the necessary and sufficient causes of the interaction.

Each molecule in PID has a defining entity, called a basic molecule. Basic molecules are distinguished by their nucleotide or amino acid sequence (for macromolecules) or by their chemical formula (for small molecules). While PID does not record the sequence of a macromolecule or the chemical formula for a small molecule, each protein or RNA is associated with a UniProt or Entrez Gene accession and most small molecules are associated with Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers. A basic molecule has a primary name and may have multiple aliases. Each molecule use, as an interactant in an interaction or as a component of a complex, references its corresponding basic molecule. Each molecule use may have additional information, including posttranslational modifications (for proteins) and cellular location and activity state (for all molecule types).

A basic protein molecule has a single identifying UniProt accession associated with a particular amino acid sequence. If the particular isoform of a protein used in an interaction is not known, then the basic protein molecule may be associated with an Entrez Gene identifier instead of a UniProt accession; in PID, this method of identifying proteins is restricted almost entirely to the uncurated section of the database imported from BioCarta. A use of a protein as a participant in an interaction or component of a complex may have additional attributes: posttranslational modifications, an abstract activity-state attribute and a cellular location attribute. Currently, PID uses 13 types of posttranslational modifications, with phosphorylation being by far the most frequently used modification (Table 3). The abstract activity-state attribute, with values such as ‘active’ and ‘inactive’, allows curators to distinguish functionally different forms of a protein even if the precise covalent modifications are not known. Values for the cellular location attribute are drawn from the Gene Ontology (GO) cellular component vocabulary (5). Cleaved subunits of a precursor protein are not distinguished by the posttranslational modification mechanism; rather they are treated as basic protein molecules separate from each other and from the precursor. However, PID explicitly relates the cleaved subunit to its precursor and records the cleavage coordinates when these are known. A PID protein corresponds roughly to a BioPAX Level 3 protein reference, while a BioPAX Level 3 protein corresponds to a PID protein use (with posttranslational modifications and cellular location).

Table 3.

Posttranslational modifications in NIC-Nature Curated data source

| Modification type | All uses | Unique modifications |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylation | 111 | 46 |

| Farnesylation | 7 | 4 |

| Geranylgeranylation | 2 | 2 |

| Glycosaminoglycan | 9 | 2 |

| Glycosylation | 135 | 15 |

| Hydroxylation | 13 | 3 |

| Methylation | 13 | 2 |

| Myristoylation | 15 | 4 |

| Oxidation | 8 | 4 |

| Palmitoylation | 52 | 14 |

| Phosphorylation | 7403 | 1070 |

| Sumoylation | 50 | 10 |

| Ubiquitination | 149 | 52 |

PID allows the definition of generic proteins, complexes, small molecules and RNA molecules. A generic molecule is called a family, but is not restricted to the traditional protein families defined by sequence similarity: any set of proteins (or other type of molecule) that are in some respect functionally equivalent may be grouped in a family. Individual protein members of a protein family may have posttranslational modifications or activity states. The family itself can be used as a participant in an interaction, or as a component of a complex.

Because data are entered by multiple curators and because the database contains data from multiple sources, PID needs rules for determining equivalence of molecules. Two basic molecules that are neither families nor complexes are equivalent if they have the same external database accession (e.g. UniProt or Entrez Gene), or if, in cases where neither has an external database accession, they have the same name. Two molecule uses (as participant in an interaction or component of a complex or member of a family) are equivalent if they refer to the same basic molecule, and have the same (or no) posttranslational modifications, and have the same (or no) activity-state attribute, and have the same (or no) cellular location attribute. Two basic families (or complexes) are equivalent, if they have the same number of members (or components) and if for each member (component) of one, there is an equivalent member (component) in the other. These rules are applied recursively to define, for example, equivalent uses of complexes with components that are families. Equivalence of molecule uses is the basis on which novel networks are constructed: any two interactions in the database may be joined in a network if one interaction has a participant that is equivalent to a participant in the other interaction. Analogous rules of equivalence are implemented for interactions and entire networks, allowing equivalent (redundant) interactions to be pruned from the novel networks.

An interaction may be supported by one or more citations to the literature. Currently, interactions in the NCI-Nature Curated data source are annotated with 3105 distinct PubMed references. In addition, an interaction may be annotated with one or more evidence codes that specify the kind of evidence adduced in the citations in support of the interaction (Table 4).

Table 4.

Evidence in NCI-Nature Curated data source

| Code | Evidence kind | Uses |

|---|---|---|

| IAE | Inferred from array experiments | 3 |

| IDA | Inferred from direct assay | 1780 |

| IEP | Inferred from expression pattern | 37 |

| IFC | Inferred from functional complementation | 13 |

| IGI | Inferred from genetic interaction | 12 |

| IMP | Inferred from mutant phenotype | 1689 |

| IOS | Inferred from other species | 1139 |

| IPI | Inferred from physical interaction | 1203 |

| RGE | Inferred from reporter gene expression | 311 |

A predefined pathway is a curated pathway representing a known biological process. At present, every pathway stored in the PID database is a predefined pathway and every interaction in the database is a member of at least one predefined pathway. However, the search and retrieval tools allow the user to compose novel pathways from interactions defined in the predefined pathways. This ability to recombine interactions and to thus create novel pathways is a distinguishing feature of PID.

Since the original BioCarta diagrams were not associated with an explicit data model, the import of the BioCarta pathway data did not challenge the PID data model. The original BioCarta diagrams show protein–protein interactions, but the semantics of the connecting arrows are implicit. The import of these pathways into PID required the interpretation of each interaction and the manual encoding of the semantics in the PID data model. This was tedious, but since the original BioCarta pathways were underspecified, the process did not entail loss of information. In contrast, the import of the Reactome data is automated but does entail some loss of information. PID uses Reactome's BioPAX export as the source for the imported Reactome data. Some features of Reactome are not expressible in BioPAX Level 2. For example, Reactome has ‘entity sets’, which correspond roughly to PID's molecule families. However, since BioPAX Level 2 lacks the means to specify an entity set, this information was lost in the import process. Along with other important enhancements, this is being corrected in BioPAX Level 3. On the other hand, Reactome has some features that are expressible in BioPAX Level 2 but have no correspondence in PID. For example, in Reactome it is possible to explicitly specify that one interaction is a predecessor (‘preceding event’) of another, and this is also directly expressible in BioPAX Level 2. However, in PID the predecessor relation is implicit, inferred from the identity of interactants and the directionality of inputs and outputs. Consequently, the predecessor relation between two Reactome interactions that do not share an interactant is lost in the PID import.

DATA CURATION

Nature Publishing Group (NPG) editors create the NCI-Nature Curated pathways. Pathways selected for curation are based on potential drug targets, suggestions made by users and reviewers, and other molecules known to be of interest to the cell signaling community. A list of NCI-Nature Curated pathways, along with a list of the pathways imported from Reactome and BioCarta, can be found on the Browse pathways page of the PID website: http://pid.nci.nih.gov/browse_pathways.shtml

In curating, editors synthesize meaningful networks of events into defined pathways and adhere to the PID data model for consistency in data representation: molecules and biological processes are annotated with standardized names and unambiguous identifiers; and signaling and regulatory events are annotated with evidence codes and references. To ensure accurate data representation, editors assemble pathways from data that is principally derived from primary research publications. The majority of data in PID is human; however, if a finding discovered in another mammal is also deemed to occur in humans, editors may decide to include this finding, but will also record that the evidence was inferred from another species. Prior to publication, all pathways are reviewed by one or more experts in a field for accuracy and completeness.

Any pathway curation effort must decide to what extent to annotate pathways and interactions with information about the larger biological context, including the cell types in which a set of interactions is known to occur and the role of individual pathways in specific pathologies. Using the GO biological process vocabulary, PID curators are able to connect interactants and interactions to macroprocesses that characterize particular cell types (e.g. ‘endothelial cell migration’). While, it would be desirable to annotate each interaction with the list of cell types in which the interaction has been observed, PID does not at present attempt to supply this level of detail. Given the sparseness of available data, it would be necessary to specify not only positive findings but also negative findings in order to prevent a lack of data from being misinterpreted as the absence of the interaction in a particular cell type. PID has a few pathways that explicitly describe a particular pathological response (e.g. ‘Cellular roles of anthrax toxin’); however, the focus of PID is normal human biology. The assumption is that a ‘pathological pathway’ relies on the signaling topology of normal biology but deviates from normal biology in quantity (e.g. overabundance of a protein), in co-occurrence (abnormal presence of two reactants at the same time in the same cellular compartment), or in the introduction of specific abnormal reactants (e.g. the anthrax toxin or the constitutively active BCR/ABL fusion protein). Curators are able to specify abnormal reactants; however, this feature has not been used extensively to date. As described in the next section, an important use of the batch query is for a researcher to overlay experimental information about such deviations onto the normal signaling topology and thus visualize possible perturbations.

WEB INTERFACE AND APPLICATION

PID provides several query options: a simple query, an advanced query, a connected molecules query and a batch query. In the simple query, the user provides the name, alias or accession of a molecule or biological process; wildcarding is permitted. The query will return a list of all uses of the molecule, as simplex or as participant in a complex, and all uses of the biological process, in the database, with hyperlinks to visualizations of the relevant predefined pathways containing the queried entities. The user also has the option to visualize the novel network(s) that include all interactions using the queried entities. The advanced query allows the user to construct the set of novel networks from interactions that: (i) involve any of a set of user-specified molecules, or (ii) are part of any predefined pathway whose name includes a user-specified key word, or (iii) have a user-specified GO biological process term or National Cancer Institute (NCI) Thesaurus (6) term as their event type or condition. An important feature of the advanced query is the provision for including interactions that are immediately upstream or downstream of the set of interactions retrieved by molecule, pathway name or GO/NCI Thesaurus term. The connected molecules query allows a user to find a novel network that connects two or more molecules specified by name, alias or accession. The query will find only one of the possibly many networks satisfying the constraint, but the one found will have the minimum number of interactions. Finally, the batch query allows a user to upload one or two lists of molecule identifiers (name, alias or accession). The user has two options: to analyze the number of molecules in the lists that ‘hit’ each predefined pathway or to construct the novel network(s) that include all interactions using any of the listed molecules. For the first option, the query uses a hypergeometric distribution to compute the probability that each pathway in the database is hit by molecules in either of the lists. The query returns a list of pathways ordered by P-value. In the visualization of a predefined pathway (first option) or novel pathway (second option), molecules from the first list are colored blue, molecules from the second list are colored red and any molecules appearing in both lists are colored purple. Supplementary Figure 1 presents an example of invoking the batch query with a single molecule list, the 120 protein kinases found by Greenman et al. (7) to have at least one cancer-predisposing mutation. Selecting the predefined pathways option, one can see that this list samples a small number of pathways, biased toward immune cell signaling, at a P < 0.0001.

While PID associates a single external database accession (typically a UniProt accession) with a protein, the query interface searches PID not only by UniProt accession, but also by related gene identifiers (HUGO symbol, alias, Entrez Gene identifier). Any predefined pathway or novel network can be visualized in either GIF (graphics interchange format) or SVG (scalable vector graphics) graphic mode. Network graphics are all automatically constructed from the underlying data using the GraphViz package (8). Events and molecule uses in the graphics are hyperlinked to HTML pages of information about the interaction or molecule. In addition, any predefined pathway or novel network can be exported in native PID XML or BioPAX Level 2 formats. Using the BioPAX export, a user can also visualize PID pathways in Cytoscape (http://cytoscape.org) a popular third-party network visualization tool (9). For any predefined pathway, the user can obtain (and export to tab-separated format) a list of literature citations and participating molecules.

DISCUSSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

PID is a highly structured, curated database of molecular interactions and events that compose human cell signaling and regulatory pathways. A particular strength of PID is the ability to create novel networks that can reveal parallel alternative paths to events of interest, like activation of a protein or disassembly of a complex in the DNA repair process. In cancer biology, such a view can elucidate the variety of strategies that a given type of cancer may adopt, explain why a single-agent therapy is not effective and suggest potential multi-agent therapies. Increasingly, molecular networks are recognized as frameworks for integrating and interpreting experimental data. For example, by using pathways as the integrating framework, the Cancer Genome Atlas project has mapped genomic abnormalities of different types—copy number, mutation and methylation—to a set of oncogenic processes (10). At present, most attempts to profile tumor subtypes have relied on DNA and RNA assays. However, as high-throughput proteomic methods improve the kind of detailed information on posttranslational modifications of proteins available in PID will be essential in mapping more accurately the state of a cell.

Consistent with its focus on interactions and events derived from curated signaling cascades and regulatory processes, PID does not at present include interaction data deriving from high-throughput protein–protein interaction experiments. This reflects not a judgment on the quality of high-throughput data, but a recognition that there are databases specifically designed to provide access to this data (11, 12, 13). However, while it does not lead directly to the construction of signaling cascades, information from high-throughput protein–protein interaction experiments can be useful in interpreting the curated pathways and assessing their completeness. For example, a high-throughput protein–protein interaction experiment can identify an unexpected binding partner for a catalyst, suggesting the possibility that the in vivo presence of the partner can sequester the catalyst and thus turn off downstream interactions. In the future, PID will allow users to take advantage of high-throughput protein–protein interaction data, either by allowing users to upload interaction sets to be added to the novel networks created by PID queries or by querying other data sources (such as Pathway Commons, http://pathwaycommons.org) as needed to support a user query. The PID data model is currently being integrated with NCI's Cancer Bioinformatics Infrastructure Objects model (caBIO) (14), thereby making PID data accessible on NCI's caGrid (15).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

The National Cancer Institute. Funding for open access charge: National Cancer Institute.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vastrik I, D’Eustachio P, Schmidt E, Joshi-Tope G, Gopinath G, Croft D, de Bono B, Gillespie M, Jassal B, Lewis S, et al. Reactome: a knowledge base of biologic pathways and processes. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R39. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-3-r39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romero P, Wagg J, Green ML, Kaiser D, Krummenacker M, Karp PD. Computational prediction of human metabolic pathways from the complete human genome. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R2. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-r2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanehisa M, Araki M, Goto S, Hattori M, Hirakawa M, Itoh M, Katayama T, Kawashima S, Okuda S, Tokimatsu T, et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D480–D484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bader GD, Cary M, Sander C. BioPAX – Biological Pathway Data Exchange Format. Encyclopedia of Genomics, Proteomics and Bioinformatics. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fragoso G, de Coronado S, Haber M, Hartel F, Wright L. Overview and utilization of the NCI thesaurus. Comp. Funct. Genomics. 2004;5:648–654. doi: 10.1002/cfg.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gansner ER, North SC. An open graph visualization system and its applications. Software Pract. Exper. 1999;(S1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cline MS, Smoot M, Cerami E, Kuchinsky A, Landys N, Workman C, Christmas R, Avila-Campilo I, Creech M, Gross B, et al. Integration of biological networks and gene expression data using Cytoscape. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2366–2382. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Nature. 2008. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. 4 September 2008 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatr-aryamontri A, Ceol A, Palazzi LM, Nardelli G, Schneider MV, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G. MINT: the Molecular INTeraction database. Nucleic Acid Res. 2007;35:D572–D574. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermjakob H, Montecchi-Palazzi L, Lewington C, Mudali S, Kerrien S, Orchard S, Vingron M, Roechert J, Wood V, et al. IntAct: an open source molecular interaction database. Nucleic Acid Res. 2004;32:D452–D455. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breitkreutz BJ, Stark C, Reguly T, Boucher L, Breitkreutz A, Livstone M, Oughtred R, Lackner DH, Bahler J, Wood V, et al. The BioGRID interaction database: 2008 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D637–D640. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Covitz PA, Hartel F, Schaefer C, De Coronado S, Fragoso G, Sahni H, Gustafson S, Buetow KH. caCORE: a common infrastructure for cancer informatics. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2404–2412. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oster S, Langella S, Hastings S, Ervin D, Madduri R, Phillips J, Kurc T, Siebenlist F, Covitz P, Shanbhag K, et al. caGrid 1.0: an enterprise Grid infrastructure for biomedical research. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2008;15:138–149. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]