Abstract

We present a database DOOR (Database for prOkaryotic OpeRons) containing computationally predicted operons of all the sequenced prokaryotic genomes. All the operons in DOOR are predicted using our own prediction program, which was ranked to be the best among 14 operon prediction programs by a recent independent review. Currently, the DOOR database contains operons for 675 prokaryotic genomes, and supports a number of search capabilities to facilitate easy access and utilization of the information stored in it.

Querying the database: the database provides a search capability for a user to find desired operons and associated information through multiple querying methods.

Searching for similar operons: the database provides a search capability for a user to find operons that have similar composition and structure to a query operon.

Prediction of cis-regulatory motifs: the database provides a capability for motif identification in the promoter regions of a user-specified group of possibly coregulated operons, using motif-finding tools.

Operons for RNA genes: the database includes operons for RNA genes.

OperonWiki: the database provides a wiki page (OperonWiki) to facilitate interactions between users and the developer of the database.

We believe that DOOR provides a useful resource to many biologists working on bacteria and archaea, which can be accessed at http://csbl1.bmb.uga.edu/OperonDB.

INTRODUCTION

In prokaryotic organisms, a substantial fraction of functionally related genes are organized into operons, each of which is a group of genes arranged in tandem on the same strand of a genome sharing a common promoter and terminator. Genes in the same operon are transcribed together as one messenger RNA. Having the knowledge of operons represents the next key step in deciphering the information encoded in a genome after its genes are identified. It represents the basis for elucidating higher level genomic structures, such as regulons and modulons as well as the cellular machineries, such as metabolic pathways and regulatory networks. In addition, operons, as the basic units of transcription and cellular functions, provide the essential information for experimental designs for studying cellular systems.

A number of operon databases are currently available on the Internet. These databases contain information with varying levels of reliability and having different emphases. For example, OperonDB contains predicted operons for 550 genomes with documented prediction sensitivity at 30–50% on Escherichia coli (1). MicrobesOnline is a database with operons for 620 genomes with prediction accuracy at 85% and 83% for E. coli K12 and Bacillus subtilis, respectively (2). ODB contains both predicted and experimentally validated operons for 203 genomes (3). RegulonDB contains experimentally validated operons and associated transcriptional regulators but for E. coli only (4), collected from the published literature. And DBTBS is a database with similar content to that of RegulonDB but for B. subtilis (5).

Among these databases, RegulonDB and DBTBS have highly reliable data but they each are only for a specific organism, while the others cover more organisms with less reliable operon data. None of these databases provide the basic operon-centric tools in support of comparative genome analyses. We believe that the biological community could benefit from having a new operon database with high-quality predicted operons as well as high coverage along with strong querying capabilities. Our DOOR (Database for prOkaryotic OpeRons) database is designed to fulfill this goal.

DATA

We have recently published a computer program for operon prediction (6), with prediction accuracy at 90.2% and 93.7% on B. subtilis and E. coli genomes, respectively, measured on experimentally validated operons. Our prediction program employs two classifiers, one for genomes with substantial numbers of experimentally validated operons and one for genomes with only limited or no such data. For the first case, our program was trained on a subset of the known operons, using a nonlinear (decision tree-based) classifier utilizing both general features of genomes and genome-specific features, while for the second case, our program was trained based only on general features of genomes, using a linear (logistic function-based) classifier. The advantage of this strategy, i.e. combining genome-independent and genome-specific information when available, is clear as the program was recently ranked as the most accurate operon prediction program in the public domain by an independent assessment of 14 operon prediction programs, across all three performance measurements: prediction sensitivity, specificity and overall accuracy (7).

Using this prediction program, we have made operon predictions for all complete prokaryotic genomes (NCBI release of 2 May 2008), and organized the data into a relational database, DOOR. Currently, DOOR contains predicted operons for 675 organisms with 736 chromosomes and 489 plasmids, consisting of a total of 450 986 operons. The RNA genes and protein-encoding genes in NCBI release are treated the same by our operon prediction program, so DOOR also contains operons for RNA genes.

For each gene and operon in DOOR, we provide the following information collected from public databases. For each gene, we include its location in the genome, the name of the genome, its gene name, its GI number, its locus tag, its COG number(s), its molecular function described using a few keywords, a label for it being a protein- or RNA-encoding gene and its genomic sequence. To facilitate operon comparisons, DOOR also contains precalculated BLAST E-values and alignment bit-scores between each pair of potentially homologous genes across all genomes (with E-values lower than a preselected threshold) (see Tools supported by DOOR section for details).

For each operon, the DOOR database contains its component genes, its precalculated promoter sequence (up to 200 bp, our default value), its precalculated similar operons, a link to the relevant literature in the ODB database (3) and a link to its corresponding operon page at MicrobesOnline.

The whole DOOR system is implemented on a Fedora Core 8 Linux computer using MySQL as the database management system. DOOR employs Apache for its web server, and php to implement the dynamic web pages. In addition, the Wiki of the DOOR system is implemented using MediaWiki 1.13.0.

TOOLS SUPPORTED BY DOOR

Currently, the DOOR system supports the following search capabilities to facilitate access to and utilization of the information stored in the database by its user. We expect that the list of tools will continue to expand in DOOR as the needs arise.

Basic querying capabilities

Searching for operons

A user can search for interested operons in DOOR by multiple ways.

(1) Find an operon by its genes. A user can first find a gene in DOOR by searching for it using various gene attributes, such as the gene name, locus tag, GI number, COG number(s), protein product description in conjunction with the organism's name. Multiple attributes can be combined using AND or OR operations, and thus complex queries can be conducted against the DOOR database. After a target gene is identified, the system returns a link to the operon that contains the gene (if such an operon exists).

(2) Find an operon by operon attributes. One can find an operon by operon attributes, such as Operon ID, operon size and the number of component genes in conjunction with the organism's name.

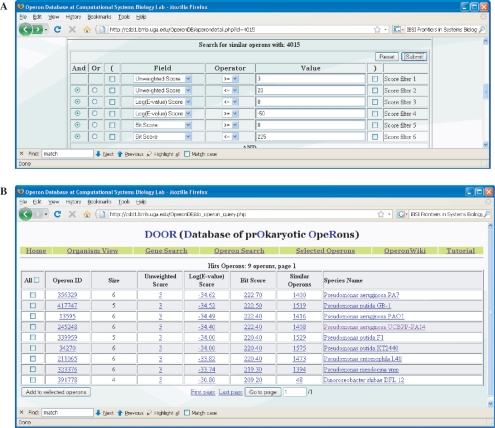

(3) Find operons by its similar operon. A user can find similar operons to a query operon in DOOR. Figure 1 shows an example of using a query operon to search for its similar operons with low homology between the corresponding genes.

Figure 1.

Find similar operons with operon 4015 by using the criterion ‘(3 ≤ Unweighted Score ≤ 20) AND (−30 ≤ Weighted Score ≤ 0) AND (0 ≤ Bit Score ≤ 225)’. (A) Is a query form. (B) Is the hit operons. Among the nine hit operons, five have not been annotated by COG.

Selecting operons

A user can browse all operons in selected genomes, and copy the operons to a working environment, where the user can carry out operations on the selected operons, such as predicting their cis-regulatory motifs.

Retrieving literature information of selected operons

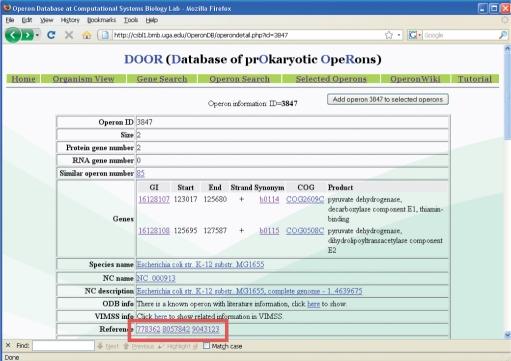

The DOOR database allows a user to output related literature for a selected operon. Figure 2 shows an example of such an application.

Figure 2.

An operon with reference information (highlighted), whose genes make the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in E. coli. The first reference is a case study in 1976, and the second and third references reported two experimental studies on this complex.

Calculating general statistics

The DOOR system provides a number of procedures for calculating various operon-related statistics for a specified genome, including (i) the distribution of the number of genes across all operons in the genome; (ii) the distributions of inter-genic distances between operons and between genes, respectively; (iii) the percentage of genes in operons (with at least two genes); (iv) the distribution of the operon lengths in term of the genomic sequence lengths covered by each operon; and (5) the correlation between operon size and its gene length. For each of these distributions, we also calculate the average, the median and the standard deviation. We expect that this list will grow as the needs arise.

Crosslinking to other operon databases

The DOOR system also provides links to other databases, currently two databases ODB and MicrobesOnline for each of its operons. The reason for linking to these databases is that ODB provides the most comprehensive literature information for operons and MicrobesOnline is the second largest operon database on the Internet. We expect that the crosslinks to other databases will grow as the needs arise and as new-related databases emerge.

Generating easy-to-read text files for specified operons and associated information

The DOOR system can generate a file containing user-specified operons and associated information in a plain text format and output it to the users’ local computer to facilitate large-scale applications by users.

Identification of similar operons

We now present a quantitative method for measuring the similarity between two operons, which generalizes the idea of ‘conserved gene pairs’ (1).

Given two operons O1 and O2, with O1 having m genes and O2 having n genes. For each pair of genes between O1 and O2, we call them homologous genes if their sequence similarity, measured by BLAST, is above a preselected cutoff. We then create a bipartite graph G, in which genes in O1 and O2 are represented as vertices and for each pair of homologous genes defined above, we create an edge between the two genes and use their sequence similarity as their weight in the graph G. The weight of the maximum weighted bipartite matching (8) for graph G is defined as the similarity score between operons O1 and O2. In the current implementation, DOOR uses the −logarithm of BLAST E-values or alignment bit-scores to measure the level of similarity between two operons. Please find a detailed explanation in the Supplementary Material.

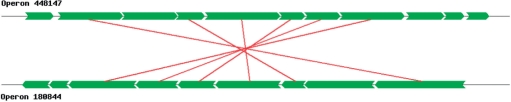

In DOOR, two operons with at least two pairs of matched genes in their maximum weighted bipartite matching are considered as similar operons. Figure 3 shows an example of two similar operons with six genes, in which pair-wise sequence similarity is not very significant, with E-values 10−8.2, 10−4.0, 10−6.1, 10−21.5, 10−3.0 and 10−2.7. These two sets of six homologous genes arranged in tandem strongly suggest that these two sets of genes are involved in the same biological pathways in their own organisms, indicating that these homologous gene pairs are orthologous.

Figure 3.

Two similar operons in Beijerinckia indica subsp. indica ATCC 9039 and Methanosphaera stadtmanae DSM 3091, each of which is represented as a sequence of green segments. Each red line connecting two genes represents a homology relationship.

We expect that as the prediction accuracy of operons continues to improve, we will soon see many operon-based comparative genome analyses. Hence a capability like the above should prove to be a useful tool in support of such operon-based analyses.

Motif finding

The DOOR system allows a user to predict cis-regulatory motifs for a given set of similar operons. For a set of operons identified to be similar, the system can retrieve the corresponding promoter sequence of each operon, and then it applies either MEME (9) or CUBIC (10), selected by the user, to find conserved sequence motifs across the promoter sequences and predict them to be cis-regulatory motifs.

OperonWiki

The DOOR system supports a wiki page (OperonWiki) to facilitate interactions between the user and the developers of the database. Our goal is to have a comprehensive set of operons for all sequenced prokaryotic genomes, which will require substantial manual curations in order to keep our operon data as accurate as possible. Our plan is that we will rely not only on our development team but also on the user community of the database to do this. We have developed a Wiki for the DOOR system to collect users’ feedbacks about our operon data and make necessary changes on the database when such suggestions are made by users after our validation.

Using the DOOR system: an example

We now give an example to illustrate how to use the search capabilities supported by DOOR. The ssuEADCB operon in E. coli has five genes, and these genes are involved in the alkanesulfonate metabolism. Our goal here is to predict the cis-regulatory motifs of this operon in E. coli through searching the DOOR database.

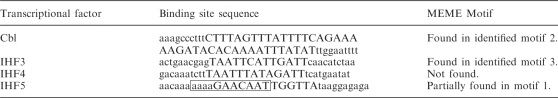

A user can go to the main page of DOOR, click on ‘Operon Search’ and then specify the query criterion ‘Operon ID = 4015’ to find this operon if the user knows its ID. Otherwise, the user can find this operon by using other information. For example, he/she can search for the operon by finding its component genes through the ‘Gene Search’ page by using the query criteria ‘(Gene Include ssu) AND (Species Name Include MG1655)’. On the query result page, click the link containing operon ID (‘4015’) to get to the detailed target operon page. The user can see that this operon has 1476 similar operons. By clicking on the link ‘1476’ on the ‘Similar Operon’ row, the user can see the list of all its similar operons. In order to apply the prediction tool for cis-regulatory motifs, the user needs to select a number of similar operons to the query operon by checking the checkbox on relevant operon rows, and then click the button ‘Add Selected Operons’, which adds all the selected operons to the working environment. To see which operons have been added to the working environment, the user can click the button ‘Selected Operons’ on the main menu. Then check the checkboxes for the interested operons and click the button ‘Show Upstream Regions’ to get and show the promoter regions of the selected operons. The user can now proceed to predict cis-regulatory motifs by either clicking on ‘Do MEME’ (or ‘Do CUBIC’), which invokes the MEME with the selected promoter sequences. In this case, the program returns the following table (Table 1) for operon ID = 4015.

Table 1.

Identified cis-regulatory binding motifs for the ssuEDACB operon (Operon ID is 4015) by MEME

|

For this particular example, we have checked which transcription factors can bind to the promoter sequences in the RegulonDB database. We found that six transcriptional factors can bind to the promoter region of the ssuEABCD operon, and the binding sites for four of them have been identified experimentally. Two of them are identified here by running MEME. We believe that the reason for failing to identify the other two motifs is due to the small number of promoter sequences that we used in this example.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Science Foundation (NSF/DBI-0354771, NSF/ITR-IIS-0407204, NSF/CCF-0621700, NSF/DBI-0542119, partial); BioEnergy Science Center grant from the Office of Biological and Environmental Research in the DOE Office of Science. Funding for open access charge: National Science Foundation (NSF/DBI-0542119).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ermolaeva MD, White O, Salzberg SL. Prediction of operons in microbial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1216–1221. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.5.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price MN, Huang KH, Alm EJ, Arkin AP. A novel method for accurate operon predictions in all sequenced prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:880–892. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okuda S, Katayama T, Kawashima S, Goto S, Kanehisa M. ODB: a database of operons accumulating known operons across multiple genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D358–D362. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gama-Castro S, Jimenez-Jacinto V, Peralta-Gil M, Santos-Zavaleta A, Penaloza-Spinola MI, Contreras-Moreira B, Segura-Salazar J, Muniz-Rascado L, Martinez-Flores I, Salgado H, et al. RegulonDB (version 6.0): gene regulation model of Escherichia coli K-12 beyond transcription, active (experimental) annotated promoters and Textpresso navigation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D120–D124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sierro N, Makita Y, de Hoon M, Nakai K. DBTBS: a database of transcriptional regulation in Bacillus subtilis containing upstream intergenic conservation information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D93–D96. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dam P, Olman V, Harris K, Su Z, Xu Y. Operon prediction using both genome-specific and general genomic information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:288–298. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brouwer RW, Kuipers OP, van Hijum SA. The relative value of operon predictions. Brief. Bioinform. 2008;9:367–375. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West DB, editor. Introduction to Graph Theory. 2nd edn. New Jersey, US: Prentice Hall; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey TL, Williams N, Misleh C, Li WW. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W369–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olman V, Xu D, Xu Y. CUBIC: identification of regulatory binding sites through data clustering. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2003;1:21–40. doi: 10.1142/s0219720003000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]