Abstract

Simple modular architecture research tool (SMART) is an online tool (http://smart.embl.de/) for the identification and annotation of protein domains. It provides a user-friendly platform for the exploration and comparative study of domain architectures in both proteins and genes. The current release of SMART contains manually curated models for 784 protein domains. Recent developments were focused on further data integration and improving user friendliness. The underlying protein database based on completely sequenced genomes was greatly expanded and now includes 630 species, compared to 191 in the previous release. As an initial step towards integrating information on biological pathways into SMART, our domain annotations were extended with data on metabolic pathways and links to several pathways resources. The interaction network view was completely redesigned and is now available for more than 2 million proteins. In addition to the standard web access to the database, users can now query SMART using distributed annotation system (DAS) or through a simple object access protocol (SOAP) based web service.

INTRODUCTION

Protein domain databases remain important annotation and research tools. Simple modular architecture research tool (SMART) is one of the earliest and was originally focused on mobile domains (1). It contains manually curated hidden Markov models for many domains, accessible via a web interface, but the data can also be downloaded. SMART still remains popular and is heavily used by the general scientific community. Here we summarize the major changes and new features that have been introduced since our last report (2).

EXPANDED DOMAIN COVERAGE

Although SMART was not intended to be exhaustive, it continues to expand its domain coverage. The current release introduces 120 new domains, with around 10% being unique to SMART, bringing the total number close to 800. Even though the rate of discovery of novel domains is falling (3,4), annotation of domains is far from being finished as many existing and known domain families have suboptimal definitions due to automatic or semiautomatic methods which are most often used to create them. Reaching a high quality of the underlying alignments requires expertise and a great amount of manual work for proper functional annotation. This is illustrated by the creation of new sequence profiles for a number of characteristic domains for a subfamily of polyketide biosynthesis proteins (PKS I). This protein family synthesizes a highly diverse group of secondary metabolites that cover many biological functions and have considerable medical relevance (5). PKS I multidomain proteins contain several predominantly enzymatic domains, used for example in the synthesis of antibiotics through different repetitive steps. PKS1 usually contain at least an acyltransferase (PKS_AT) domain, a ketoacylsynthase domain (PKS_KS) and an acyl carrier protein (PKS_PP) domain. Additionally ketoreductase (PKS_KR), dehydratase (PKS_DH), enoylreductase (PKS_ER), methyltransferase (PKS_MT) and thioesterase (PKS_TE) domains can be found. As PKS1 are homologous to several enzymes in fatty acid biosynthesis, current profiles are not able to distinguish between the two functionalities. Our new, hand-adjusted multiple sequence alignments and derived hidden Markov models allow, with manually established cut-offs, to selectively identify PKS1 above the background of many related enzymes such as fatty acid synthases. The selection of cut-offs for individual domains was based on a sophisticated tree-building procedure (6).

NEW AND UPDATED PROTEIN DATABASES

Protein database redundancy creates significant difficulties in the protein domain architecture analyses. Users looking at genome wide domain counts often end up with wrong and highly inflated numbers. To remedy this problem, in the previous release of SMART (2), we have introduced a ‘genomic’ analysis mode, which uses only proteins from the completely sequenced genomes. In the initial release, this protein database included 170 genomes, which were available in SWISS-PROT (7) and ENSEMBL (8). With the new release of SMART, we have greatly expanded this database and it now contains proteins from 630 completely sequenced genomes (55 Eukaryota, 46 Archaea and 529 Bacteria).

In addition to the expanded genomic mode protein database, SMART uses a new procedure to create the default nonredundant protein database that is used in the ‘normal’ analysis mode. The main source of protein sequences is Uniprot (9), complemented with the full set of stable genomes from ENSEMBL. To reduce the high redundancy that is inherently present in these databases, we have implemented a per-species protein clustering procedure. All the proteins are initially separated into species-specific databases. Each of these databases is clustered separately using the CD-HIT algorithm (10) with a 96% identity cutoff. Longest members of each cluster are used as ‘representatives’, and are the only proteins included in the database, together with non-clustered ones. This procedure significantly improves the results of all domain architecture queries and brings the domain counts to lower levels, comparable to the genomic mode database.

INTEGRATION OF BIOLOGICAL PATHWAYS DATA

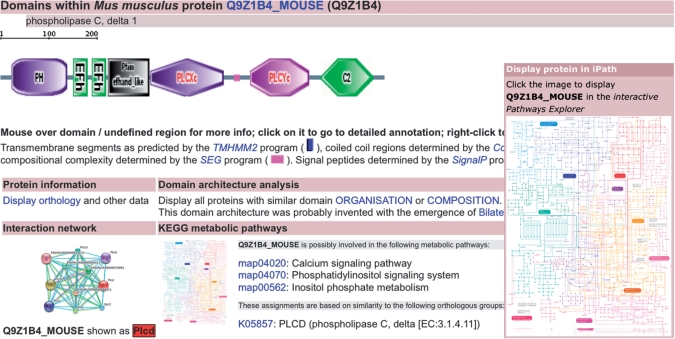

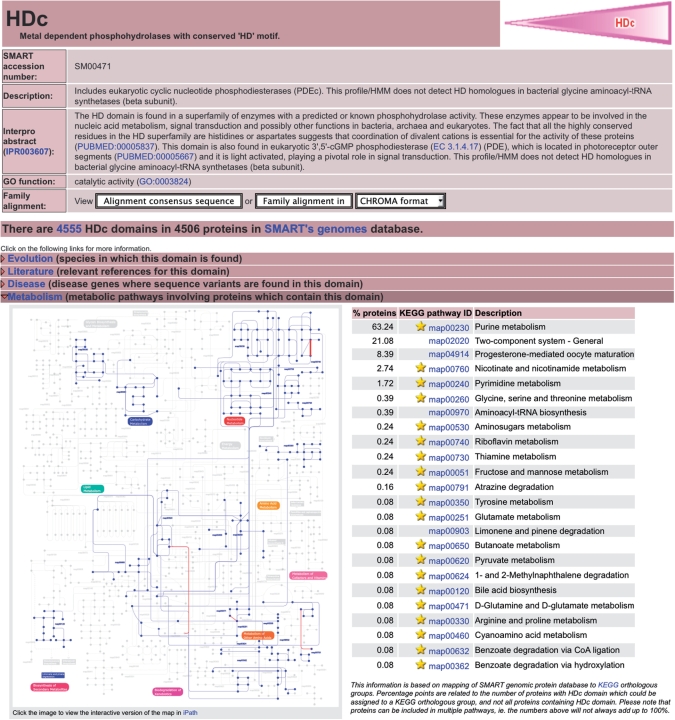

In the current release, we have started the integration of biological pathways information into SMART. Initially, this will be limited to the metabolic pathways, with further expansions coming in the future releases. We have mapped the complete genomic mode protein database to the KEGG (11) orthologous groups and their corresponding metabolic pathways. This information is available directly in the protein annotation pages, for more than 1 million proteins (Figure 1). Additionally, this information was used to generate the overview of various domains’ presence in different parts of metabolism. Each domain's annotation page includes a new ‘Metabolic pathways’ entry, which lists the pathways where the domain is present (Figure 2). In addition to the basic statistics, the metabolic pathways information for both proteins and domains is also displayed on the global overview map of the metabolism (11), with an interactive version of the maps provided by iPath, the interactive Pathways Explorer (12).

Figure 1.

Protein annotation page for Mus musculus phospholipase C, delta 1. More than 600 000 proteins are linked to the KEGG metabolic pathways and orthologous groups, and can be displayed in the interactive Pathways Explorer (12), which provides an interactive, global overview map of the metabolism. Interaction network information has been greatly expanded, and is available for about 2.5 million proteins.

Figure 2.

SMART annotation page for the HDc domain. A new feature of SMART domain annotation pages is the ‘Metabolism’ entry. Based on the mapping of SMART genomic protein database to KEGG orthologous groups, it gives an overview of the domain's presence in various metabolic pathways. Matching pathways are also displayed on the global metabolism overview map (11), with a link to the interactive version, provided by the interactive Pathways Explorer.

EXPANDED PROTEIN INTERACTION DATA

The expansion of the protein database based on completely sequenced genomes allowed SMART to significantly extend the information on putative protein interaction partners. This data is now available for about 2.5 million proteins, compared to 350 000 in the previous release. Interaction network data has been expanded and updated, and is displayed using completely redesigned summary graphics, which are easier to read and interpret. The data has been imported from the STRING database (13), and is synchronized with its version 8 release.

DATABASE AND WEB SERVER OPTIMIZATIONS

With the ever-increasing amount of sequence information available, domain annotation tools such as SMART face constant new challenges in providing fast and user-friendly interfaces to the underlying data. The core of SMART is a relational database management system (RDBMS), which stores the annotation of all SMART domains and the pre-calculated protein analyses for complete Uniprot (9) and Ensembl (8) sequence databases. In order to keep the response times of the server acceptable, many parts of the database access code have been greatly optimized, and the database itself restructured. Additionally, the server was distributed onto a hardware cluster with different tasks assigned to dedicated machines, resulting in a greatly expanded load capacity.

USER INTERFACE IMPROVEMENTS AND TECHNICAL CHANGES

Many parts of SMART's web interface have been updated and streamlined. Protein analysis pages now include extended information on all detected SMART domains, which is dynamically loaded on user request. In addition to SMART domains, we now also display the basic annotation for all detected Pfam (14) domains, such as Interpro (15) abstract and annotated Gene Ontology (16) terms.

Domain annotation pages have also been redesigned and updated. Information on domain presence in 3D structures has been expanded and includes PDB (17) titles and the basic graphical representation of the structure.

With version 6, SMART offers two new modes of database access, oriented towards advanced users. Distributed annotation system (DAS, 18), allows access to sequence annotation data on an as-needed basis, and offers users an easy way of integrating multiple annotation sources in a single client-side interface. SMART domain annotations for the complete Uniprot and Ensembl protein databases are accessible as DAS XML at the URL http://smart.embl.de/smart/das.

In addition to DAS, SMART can also be accessed through a web service, with a web service definition language (WSDL) service description file available at http://smart.embl.de/webservice. SMART web service uses simple object access protocol (SOAP) for all input and output messages and accepts both protein sequence identifiers and raw amino acid sequences.

These new access modes offer simpler integration of SMART annotation data into other resources and an easier way for analysis of large datasets.

CONCLUSION

Since the initial conception of SMART in the mid 1990s, our goal has been to provide a useful biological web resource, characterized by high quality of underlying data and a powerful, simple user interface. We continue to modestly expand our coverage and implement new features to make using SMART a better and more enjoyable experience to both existing and new users.

FUNDING

Funding for open acess charge: EMBL (European Molecular Biology Laboratory).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P, Ponting CP. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5857–5864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Letunic I, Copley RR, Pils B, Pinkert S, Schultz J, Bork P. SMART 5: domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D257–D260. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Copley RR, Doerks T, Letunic I, Bork P. Protein domain analysis in the era of complete genomes. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:129–134. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heger A, Holm L. Exhaustive enumeration of protein domain families. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;328:749–767. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staunton J, Weissman KJ. Polyketide biosynthesis: a millennium review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001;18:380–416. doi: 10.1039/a909079g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foerstner KU, Doerks T, Creevey CJ, Doerks A, Bork P. A computational screen for type I polyketide synthases in metagenomics shotgun data. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003515. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boeckmann B, Bairoch A, Apweiler R, Blatter MC, Estreicher A, Gasteiger E, Martin MJ, Michoud K, O’Donovan C, Phan I, et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:365–370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flicek P, Aken BL, Beal K, Ballester B, Caccamo M, Chen Y, Clarke L, Coates G, Cunningham F, Cutts T, et al. Ensembl 2008. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D707–D714. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The UniProt Consortium. The universal protein resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D190–D195. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanehisa M, Araki M, Goto S, Hattori M, Hirakawa M, Itoh M, Katayama T, Kawashima S, Okuda S, Tokimatsu T, et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D480–D484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Letunic I, Yamada T, Kanehisa M, Bork P. iPath: interactive exploration of biochemical pathways and networks. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008;33:101–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Mering C, Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Chaffron S, Doerks T, Kruger B, Snel B, Bork P. STRING 7–recent developments in the integration and prediction of protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D358–D362. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finn RD, Tate J, Mistry J, Coggill PC, Sammut SJ, Hotz HR, Ceric G, Forslund K, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer EL, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D281–D288. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulder NJ, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Binns D, Bork P, Buillard V, Cerutti L, Copley R, et al. New developments in the InterPro database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D224–D228. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology (GO) project in 2006. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D322–D326. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westbrook J, Feng Z, Chen L, Yang H, Berman HM. The Protein Data Bank and structural genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:489–491. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowell RD, Jokerst RM, Day A, Eddy SR, Stein L. The distributed annotation system. BMC Bioinformatics. 2001;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]