Abstract

Batesian mimicry is a fundamental example of adaptive phenotypic evolution driven by strong natural selection. Given the potentially dramatic impacts of selection on individual fitness, it is important to understand the conditions under which mimicry is maintained versus lost. Although much empirical and theoretical work has been devoted to the maintenance of Batesian mimicry, there are no conclusive examples of its loss in natural populations. Recently, it has been proposed that non-mimetic populations of the polytypic Limenitis arthemis species complex represent an evolutionary loss of Batesian mimicry, and a reversion to the ancestral phenotype. Here, we evaluate this conclusion using segregating amplified fragment length polymorphism markers to investigate the history and fate of mimicry among forms of the L. arthemis complex and closely related Nearctic Limenitis species. In contrast to the previous finding, our results support a single origin of mimicry within the L. arthemis complex and the retention of the ancestral white-banded form in non-mimetic populations. Our finding is based on a genome-wide sampling approach to phylogeny reconstruction that highlights the challenges associated with inferring the evolutionary relationships among recently diverged species or populations (i.e. incomplete lineage sorting, introgressive hybridization and/or selection).

Keywords: wing pattern evolution, mimicry, amplified fragment length polymorphism, Limenitis, phylogeny, gene flow

1. Introduction

Batesian mimicry is a classic example of adaptation because the mimic gains a direct fitness advantage (e.g. reduced predation) due to its phenotypic resemblance to the protected model. Although the relationship between a Batesian mimic and its model can vary both temporally (Waldbauer 1988) and spatially (Ritland & Brower 2000; Ries & Mullen 2008), in the simplest iteration, the fitness of a palatable Batesian mimic is dependent on the frequency of a chemically defended, and typically aposematic, model (Bates 1862; Fisher 1930; reviewed by Mallet & Joron 1999).

Under frequency-dependent selection (Fisher 1930; Ayala & Campbell 1974), protection from predation for Batesian mimics is expected to break down (i) in the absence of the model (Wallace 1870; Waldbauer & Sternburg 1987; Waldbauer 1988; Pfennig et al. 2001, 2007) or (ii) when the mimic becomes abundant relative to the model (Fisher 1930; Brower & Brower 1962; Huheey 1964; Oaten et al. 1975; Getty 1985; Mallet & Joron 1999; Harper & Pfennig 2007). Although numerous laboratory (Brower 1960; Nonacs 1985; Lindström et al. 2004; Rowland et al. 2007) and theoretical (Huheey 1976, 1988; Ruxton et al. 2004; Mappes et al. 2005) studies support these predictions, empirical examples of mimetic breakdown in natural populations are relatively rare (but see Harper & Pfennig 2007, 2008; Joron 2008).

One putative example of mimetic breakdown is represented by the phenotypic transition zone between mimetic and non-mimetic admiral butterfly populations, which comprise the polytypic Limenitis arthemis complex. White-banded populations of these butterflies (Limenitis arthemis arthemis and Limenitis arthemis rubrofasciata) range widely from northeastern to northwestern North America, as far west as Alaska (Scott 1986), and closely resemble the ancestral wing pattern phenotype characteristic of the entire genus (Mullen 2006). By contrast, red-spotted purples (Limenitis arthemis arizonensis and Limenitis arthemis astyanax) are allopatrically distributed in southwestern North America and the southeastern United States, and are well-known Batesian mimics of the chemically defended Pipevine swallowtail (Battus philenor; Brower & Brower 1962; Platt et al. 1971; Platt 1975; Mullen 2006). A recent study on the evolutionary relationships among the North American representatives of this genus has tested the hypothesis that an adaptive Batesian mimicry phenotype was lost in white-banded populations of the L. arthemis species complex (Prudic & Oliver 2008). The results of this study posit that selection for mimicry breaks down outside the range of the model (Battus), and consequently that white-banded populations of L. arthemis are the result of an evolutionary reversal by loss of the mimetic phenotype (figure 1).

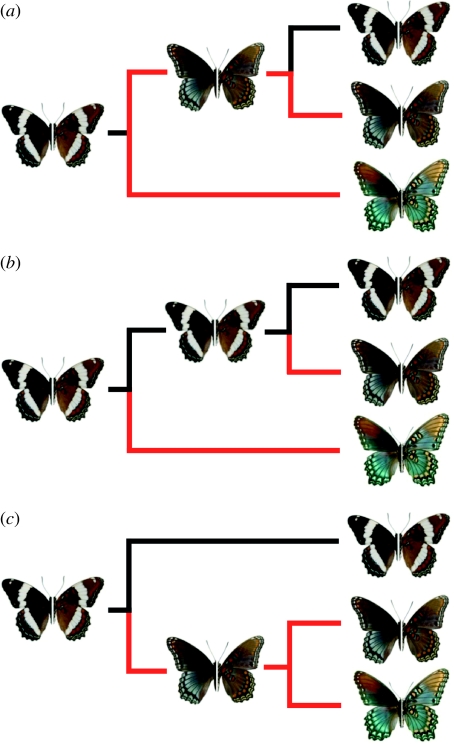

Figure 1.

Addressing the gain/loss of mimicry based on parsimony inference of a single locus leaves several alternative explanations that are equally likely. (a) The first scenario demonstrates the reversion to the ancestral white-banded wing pattern proposed by Prudic & Oliver (2008), which does not address the two mimetic forms in the complex demonstrated in (b) the second scenario. In this case, two independent origins of mimicry with no reversal in the white-banded form is an equally parsimonious scenario to (a). (c) The third scenario is the only topology that resolves both the origin of mimicry and the maintenance of the ancestral wing pattern. Resolving which of these scenarios are supported by genetic data will provide important conclusions to inferring the evolution of mimicry in the L. arthemis complex. For each of the above scenarios, the terminal taxa are L. a. arthemis, L. a. astyanax and L. a. arizonensis. Red branches indicate adaptive mimicry evolution.

If true, this finding represents the only documented example (in butterflies) of a reversion to the ancestral phenotype because of selection against mimicry. Although several recent studies have found evidence for a breakdown of selection favouring Batesian mimicry phenotypes in allopatry (with respect to the model; Harper & Pfennig 2007, 2008; Pfennig et al. 2007), none of these studies explicitly addressed the origin of the allopatric mimetic populations. Allopatric Batesian mimics could arise via several mechanisms, including range expansion of the mimic, range contraction of the model or gene flow into non-mimetic allopatric populations. Thus, although there is clear evidence that selection for mimicry breaks down outside of the range of the Battus model in this system (Prudic & Oliver 2008; Ries & Mullen 2008), there are several reasons to question the conclusion that the absence of mimicry in white-banded populations represents an evolutionary loss of mimicry.

First, if the absence of mimicry in white-banded populations of L. a. arthemis was the result of population expansion to regions outside the range of the model, then there is no a priori reason to expect evidence of genetic differentiation between mimetic and non-mimetic populations except for those regions of the genome controlling wing pattern. This is not the case because significant population structure corresponding to wing pattern phenotypes exists in this complex (Mullen 2006; Mullen et al. 2008; Prudic & Oliver 2008), consistent with the hypothesis that the hybrid zone between mimetic (L. a. astyanax) and non-mimetic (L. a. arthemis) subspecies is the result of secondary contact between two evolutionarily distinct lineages that diverged in allopatry (Mullen et al. 2008). Second, significant levels of both contemporary and historical gene flow have occurred between these two wing pattern forms, indicating that, although partially isolated, for many loci individual gene tree topologies will not accurately represent the true ‘species’ history (Pamilo & Nei 1988; Maddison 1997; Nichols 2001). Third, despite its wide use in phylogeny reconstruction, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is notoriously unreliable when used to infer the history of a phenotypic trait among recently diverged hybridizing taxa (Ballard & Whitlock 2004). Finally, the conclusion that mimicry was lost in this complex was largely based on (i) a species tree estimated from mtDNA, and (ii) the assumption that no mtDNA introgression occurs between mimetic and non-mimetic phenotypes (figure 1a; Prudic & Oliver 2008). However, an equally parsimonious interpretation is that mimicry evolved independently to give rise to both mimetic subspecies in this complex and was not lost in L. a. arthemis (figure 1b). Alternatively, it is possible that mimicry evolved once and the mimetic lineages diverged in allopatry (figure 1c).

Given that inferences about wing pattern evolution in this group so directly hinge upon a robust reconstruction of the relationships among the three subspecies, we used amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers to assay genetic variation at a genome-wide scale. AFLP fingerprinting often provides resolution in molecular phylogenies where nucleotide sequence data fail to recover relationships in recently evolved taxa (Sullivan et al. 2004; Bonin et al. 2005; Mendelson & Shaw 2005; Mendelson et al. 2005; Althoff et al. 2007; Meudt & Clarke 2007; Holland et al. 2008). Here, we present a phylogeny of the North American species of Limenitis, which indicates that mimicry evolved once in the L. arthemis complex, and that the hybrid zone between mimetic and non-mimetic populations is the result of secondary contact between two distinct lineages, rather than the loss of mimicry due to range expansion and primary differentiation.

2. Material and methods

(a) Taxon sampling

Because the species-level phylogeny of this genus has previously been published (Mullen 2006), this study focused specifically on the unresolved relationships among mimetic and white-banded phenotypes within the polytypic L. arthemis species complex. Previous work also indicates ongoing gene flow among subspecies within this group (Mullen et al. 2008), so we restricted our phylogenetic sampling of the two eastern subspecies (L. a. arthemis and L. a. astyanax) to populations well outside the region where the two subspecies are known to hybridize (Mullen et al. 2008; Ries & Mullen 2008); the third subspecies, L. a. arizonensis, is reproductively isolated de facto due to its range allopatry.

In total, we included eight Limenitis taxa, three of which are contained in the L. arthemis complex. Each taxon is represented by at least two specimens from a single locality. The total dataset consists of 24 Limenitis specimens, out of which 20 represent six North American wing pattern races (i.e. species and subspecies) and four Palaearctic representatives of admiral butterflies (Limenitis). The four Palaearctic specimens were used for Nearctic–Palaearctic out-group comparison/character polarization. Our geographical sampling and total sample sizes are restricted because three recent works have thoroughly established the weak geographical population structure of each wing pattern race, and that sampling large numbers of individuals from throughout the range does not improve resolution (Mullen 2006; Mullen et al. 2008; Prudic & Oliver 2008). In this study, we are conducting a genome-wide analysis of mimicry evolution, not of phylogeographic relationships. Specimens, locality information and wing pattern phenotypes are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Specimen information for eight wing pattern races of Limenitis examined in this study. (Listed by taxon is the sample size (N), collection locality, collection date, phenotype and the pattern of mimicry (with the model species).)

| species | N | locality | date | wing pattern | mimicry pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limenitis arthemis group | |||||

| L. a. arizonensis | 3 | Arizona, USA | 2001 | black | Batesian (Battus philenor) |

| L. a. arthemis | 4 | New Brunswick, CA | 2004 | white-banded | non-mimetic |

| L. a. astyanax | 4 | Mississippi, USA | 2001 | black | Batesian (Battus philenor) |

| Limenitis lorquini | 4 | British Columbia, CA | 2002 | white-banded, orange tip | Batesian (Adelphia) |

| Limenitis weidemeyerii | 3 | South Dakota, USA | 2003 | white-banded | non-mimetic |

| Limenitis archippus lahontani | 4 | Nebraska, USA | 2003 | orange | Müllerian (Danaus) |

| Limenitis populi | 2 | Sweden | 2002 | white-banded | non-mimetic |

| Limenitis reducta | 2 | France | 2002 | white-banded | non-mimetic |

(b) AFLP methods

Genomic DNA was isolated from flight muscle tissue using a commercially available extraction kit (DNeasy Tissue Kit, Qiagen). DNA concentrations were standardized by spectrophotometry for subsequent molecular applications. We used the AFLP Plant Mapping Kit (Applied Biosystems) and a standard protocol (Vos et al. 1995; Bonin et al. 2005) to genotype the 24 specimens with eight EcoRI–MseI selective primer combinations (table 2). The basic steps were performed as follows: (i) restriction enzyme digestion of genomic DNA and ligation with EcoRI and MseI adaptors, (ii) dilution of restriction–ligation products and preselective amplification with primers containing single nucleotide additions, and (iii) selective amplification with three nucleotide additions to the fluorescently labelled 5′ oligonucleotides. The AFLP fragments were sized with ROX-500 (−250) standard and capillary electrophoresis on an ABI Prism 3730 DNA analyser (Applied Biosystems), and scored by the absence/presence of peaks using Genemapper software v. 3.7 (Applied Biosystems). Fragments were scored according to Genemapper settings suggested by Holland et al. (2008), using bin widths of 0.5 but raising the minimum relative fluorescent units value to 100 to exclude incorrectly assigned peaks that result from background noise and stutter. Fragments were scored in the 100–400 bp range; raising the minimum size threshold was recently suggested as a step that minimizes homoplasy that is more prevalent in smaller fragments (Althoff et al. 2007).

Table 2.

Summary statistics derived from eight AFLP primer pair combinations for eight Limenitis species. (The number of fragments and the genetic differentiation estimates (FST) are listed along with the percentage of polymorphic bands for each primer pair combination. The percentage of polymorphic bands is also listed for each taxon at each primer pair combination.)

| 5-FAM-5′ | NED-5′ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EcoRI-MseI primers | ACT-CTC | ACT-CTG | ACA-CTC | ACA-CTG | AAC-CAA | AAC-CAT | AAC-CTA | AAC-CTT | total |

| number of fragments | 342 | 277 | 332 | 314 | 214 | 231 | 236 | 316 | 2262 |

| FST | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.18 |

| percent polymorphic | 86.3 | 79.1 | 86.4 | 90.1 | 81.3 | 77.1 | 80.1 | 79.1 | 82.9 |

| Limenitis arthemis group | |||||||||

| L. a. arizonensis | 28.4 | 26.4 | 21.1 | 30.6 | 30.4 | 22.5 | 34.3 | 25.0 | 27.1 |

| L. a. arthemis | 25.7 | 23.8 | 21.5 | 28.3 | 22.4 | 23.4 | 30.1 | 28.8 | 25.6 |

| L. a. astyanax | 25.7 | 21.3 | 25.1 | 28.7 | 28.5 | 29.0 | 29.7 | 23.7 | 26.2 |

| Limenitis lorquini | 35.7 | 26.7 | 34.4 | 33.8 | 15.9 | 28.1 | 29.7 | 30.7 | 30.2 |

| Limenitis weidemeyerii | 20.8 | 17.3 | 15.4 | 26.1 | 16.8 | 18.6 | 24.2 | 21.2 | 20.1 |

| Limenitis archippus lahontani | 21.6 | 21.3 | 39.3 | 32.2 | 22.9 | 16.9 | 21.6 | 21.5 | 25.3 |

| Limenitis populi | 17.0 | 12.3 | 15.1 | 18.5 | 18.2 | 24.2 | 25.8 | 16.5 | 18.0 |

| Limenitis reducta | 13.7 | 15.2 | — | 18.2 | 9.8 | 23.8 | 11.0 | 14.9 | 15.7 |

(c) Data analysis

The presence–absence of peaks for each AFLP primer pair was converted into a binary data matrix (0 or 1) for all individuals. We used AFLP-SURV v. 1.0 (Vekemans 2002) to calculate genetic diversity and basic summary statistics for each of the eight taxa. Genetic diversity was estimated with Zhivotovsky's (1999) Bayesian method of computation with a non-uniform prior distribution.

We analysed the binary matrix with four different phylogenetic methods: tree reconstructions using distance; neighbor-joining (NJ); and parsimony were calculated in PAUP* v. 4.0b10 (Swofford 2000); and Bayesian inference (BI) was performed using MrBayes v. 3.1.2 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003). The restriction-site distance measure of Nei & Li (1979) was used for computing distance and NJ trees with the minimum evolution objective function. Clade support was evaluated by 5000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates for both distance (full heuristic search) and NJ methods, both under the Nei & Li (1979) distance measure. Parsimony estimation was performed under default assumptions and settings for the binary character state matrix, and clade support was also estimated with 5000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates.

BI was conducted assuming the F81-like restriction site model implemented in MrBayes with the noabsencesites coding bias correction (Ronquist et al. 2005; Koopman et al. 2008). The two-state model implemented in MrBayes understates the complex genetic processes of AFLP evolution, and thus is less likely than distance and NJ methods to provide accurate inference of phylogeny (Althoff et al. 2007; Luo et al. 2007; Holland et al. 2008). A new Bayesian model using AFLP marker lengths was recently described by Luo et al. (2007), but it has yet to overcome the computational challenges associated with large datasets (it takes weeks to analyse a small dataset; Luo et al. 2007; Koopman et al. 2008). The Dirichlet prior for the state frequencies set to (7.3, 1.0) to match the empirical (0-1) frequencies in the dataset. The Bayesian analysis was performed with two runs of 2×107 generations each, with 10 independent chains per run, sampling frequency of 2000 generations and a burn in of 5000 samples. Burn in was determined by post-run evaluation of the potential scale reduction factor convergence diagnostic (Gelman & Rubin 1992) and stationarity of log-likelihoods. Clade credibility values are discussed where they conflict with bootstrap results.

3. Results

(a) AFLP variability

The eight AFLP primer pairs yielded 1875 segregating fragments out of 2262 total amplified bands; for each per primer pair, the number of amplified fragments ranged from 214 to 342. The total number of polymorphic fragments per taxon ranged from a low of 356 in Limenitis reducta to a high of 682 in Limenitis lorquini (table 2). Total gene diversity for the complete taxon set was 0.133, and overall FST was 0.184. Nei's genetic distances ranged from 0.008 to 0.012 within the L. arthemis complex, with the maximum genetic distance between Limenitis weidemeyerii and L. reducta (0.063; data not shown). Primer pair and per taxon results of AFLP are summarized in table 2. The AFLP distances are, as expected, much greater between Limenitis taxa, but are similar in relative differences to the uncorrected p-distances for mitochondrial and nuclear sequence data between taxa (table 3; Mullen 2006).

Table 3.

Pairwise divergence values (uncorrected p-distances) for combined mitochondrial cob1–cob2 sequences (below diagonal) and translation elongation factor 1 alpha (data from Mullen 2006). (Members of the L. arthemis complex are the first three taxa listed.)

| taxon | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L. a. arizonensis | — | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 2.3 |

| 2 | L. a. arthemis | 2.6 | — | 0.2 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| 3 | L. a. astyanax | 1.8 | 2.6 | — | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| 4 | L. lorquini | 2.6 | 3.1 | 2.4 | — | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 2.1 |

| 5 | L. weidemeyerii | 2.5 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 2.0 | — | 1.0 | 1.4 | 2.3 |

| 6 | L. archippus lahontani | 3.6 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.1 | — | 1.7 | 2.5 |

| 7 | L. populi | 8.3 | 8.5 | 8.3 | 8.1 | 7.7 | 8.2 | — | 1.9 |

| 8 | L. reducta | 8.6 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 10.9 | — |

(b) AFLP phylogeny

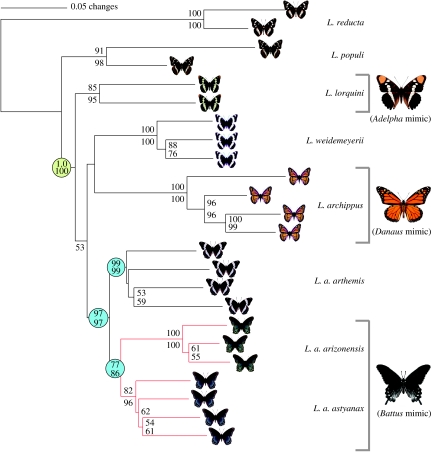

All four phylogenetic methods (distance, NJ, parsimony and BI) based on the AFLP data recovered the same general topology illustrated in figure 2. The major result of these methods indicates that (i) named Limenitis species and subspecies all form monophyletic lineages, and (ii) the two mimetic lineages of L. arthemis (L. a. astyanax and L. a. arizonensis) form a clade that is sister to the white-banded form (L. a. arthemis). For the first of these results, nodes are strongly supported under all four methods of phylogeny reconstruction with high bootstrap (distance, NJ and parsimony) and clade credibility values (BI). The second result is moderately supported under both distance-based methods, which are widely used methods with dominant data-like AFLPs (e.g. Mendelson et al. 2005), but poor support under the parsimony and BI analyses. However, both of these methods did recover the same topological relationship of the L. arthemis complex: (L. a. arthemis (L. a. astyanax and L. a. arizonensis)), and the weaker support is not unexpected given the poor fit of these two models for AFLP data (Althoff et al. 2007; Luo et al. 2007; Koopman et al. 2008) and the evidence for hybridization between the two eastern wing pattern races (Mullen et al. 2008).

Figure 2.

Inferred relationships for eight species of admiral butterflies (Limenitis) based on 2262 AFLP fragments. The white-banded wing pattern is the ancestral state (vertical black bar on right of tree), with mimetic wing patterns and the model (on right). Branch support values were derived from Nei & Li (1979) restriction-site distances for both NJ (above) and distance bootstrap indices (below). The monophyly of the Nearctic Limenitis is supported by analyses of nuclear and mitochondrial genes (yellow circle; Mullen 2006; Prudic & Oliver 2008); reported at this node are the Bayesian posterior probability and parsimony bootstrap values for this clade from both studies. Limenitis arthemis is a well-supported group (blue circles), with the white-banded race sister to a monophyletic clade that contains both of the mimetic forms of L. arthemis (red branches). The loss of mimicry is not supported, but in fact there is a monophyletic group of mimics (L. a. arizonensis and L. a. astyanax) that suggest mimicry evolved once in the mimetic L. arthemis.

Figure 2 illustrates the general AFLP-based topology of the Limenitis taxa sampled here, as well as the lack of resolution at deeper phylogenetic depths among Limenitis lineages. While distance and NJ methods resolved the same topologies and similar bootstrap support values among lineages within the Nearctic Limenitis group, none of the four phylogenetic methods resolved the Nearctic Limenitis as a monophyletic clade (yellow node, figure 2); however, this relationship is well supported by previous phylogenetic analyses that used mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequence data (see Mullen 2006; Prudic & Oliver 2008). Similarly, our AFLP phylogeny did not resolve the relationship between the Palaearctic taxa (Limenitis populi and L. reducta) and the Nearctic Limenitis taxa, but previous work by Mullen (2006) and Prudic & Oliver (2008) suggests that L. populi shared an ancestor with the Nearctic species more recently than L. reducta. Among the Nearctic taxa, each species is recovered as a strongly supported monophyletic lineage, but the relationships among L. lorquini, L. weidemeyerii, L. archippus and L. arthemis were unresolved. This is consistent with previous efforts to reconstruct the relationships among the Nearctic taxa (Mullen 2006; Prudic & Oliver 2008), which each failed to strongly resolve the pattern of speciation in this group.

In general, nodes supported by distance and NJ bootstrap pseudoreplicates based on the AFLP data had lower support in parsimony and Bayesian methods. Specifically, these latter two methods both recovered the focal mimetic clade (L. a. astyanax and L. a. arizonensis), but with lower clade credibility and bootstrap values (0.64 and 56%, respectively) relative to the higher bootstrap support values obtained by distance and NJ analyses (86 and 77%, respectively). Thus, two phylogenetic methods recover moderate support for a mimetic clade of L. arthemis, and two provide weaker inference but still recover the same topology.

4. Discussion

Recently, it has been proposed that the absence of mimicry among white-banded populations of L. arthemis represents the evolutionary loss of mimicry, which would be the first documented example of a reversion to an ancestral wing pattern phenotype (Prudic & Oliver 2008). If true, this conclusion has important implications for the maintenance of Batesian mimicry and the flexibility of the genome to respond to differential environmental pressures (i.e. selection). However, as Barton & Hewitt (1985) first pointed out, it is important to distinguish between the history of a phenotypic trait (e.g. mimicry) and the history of populations exhibiting that trait. Because the former will often be inaccessible due to the confounding effects of reticulate population histories and stochastic evolutionary and ecological processes, the resolution of how many times mimicry arose and/or was lost in the L. arthemis complex remains elusive.

The results of this study, based on a large dataset consisting of a genome-wide sampling of nuclear markers, indicate that the two mimetic (L. a. arizonensis and L. a. astyanax) subspecies in the L. arthemis complex are a monophyletic lineage, which is a sister group to the white-banded, non-mimetic subspecies (L. a. arthemis; figure 2). Thus, we find a singular origin of mimicry in the L. arthemis clade (L. a. arizonensis and L. a. astyanax) and retention of the ancestral white-banded phenotype (L. a. arthemis), where the model species (B. philenor) does not occur. However, consistent with previous attempts to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships in this genus (Mullen 2006; Mullen et al. 2008; Prudic & Oliver 2008), we were unable to resolve the basal relationships among the Nearctic species (figure 2).

Although concerns about AFLPs have been raised, recent work indicates that homoplasy can be significantly reduced by implementing strict scoring parameters (Althoff et al. 2007; Holland et al. 2008). In the case of this study, the genome size of Limenitis is approximately 380 Mb (S. P. Mullen 2009, unpublished data), placing it well within the range where the average fragment homology is quite high across species (89%; Althoff et al. 2007). In addition, the advantage of employing a large number of genome-wide markers for phylogeny reconstruction is that it avoids many of the problems associated with single-locus inference among recently diverged taxa, as demonstrated by an increasing number of recent studies (Kardolus et al. 1998; Albertson et al. 1999; Baayen et al. 2000; Bakkeren et al. 2000; Ganter & Lopes 2000; Hodkinson et al. 2000; van Raamsdonk et al. 2000; Giannasi et al. 2001; Parsons & Shaw 2001; Buntjer et al. 2002; Allender et al. 2003; Després et al. 2003; Brouat et al. 2004; Sullivan et al. 2004; Bonin et al. 2005; Mendelson & Shaw 2005; Mendelson et al. 2005). In fact, given the expectation that hybridization among mimetic and non-mimetic populations should lead to substantial introgression of neutral markers, the nodal support for a single origin of mimicry is surprisingly high, a result that is inconsistent with the conclusion that mimicry was lost in white-banded populations. Therefore, it is likely that incomplete lineage sorting and/or introgression (Funk & Omland 2003; Anderson et al. 2009) have confounded previous efforts to recover the history of wing pattern evolution in this group.

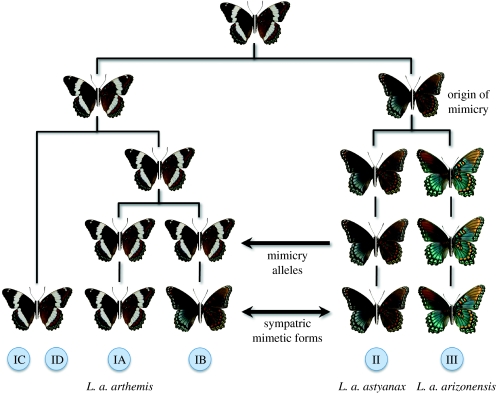

Although examples of mitochondrial introgression are common (e.g. Krosby & Rohwer 2009; Shaw 2002), an alternative interpretation of the mitochondrial data presented in Mullen (2006), Mullen et al. (2008) and Prudic & Oliver (2008) is that southeastern populations of mimetic L. a. astyanax historically came into contact with a lineage of white-banded L. a. arthemis in sympatry with Battus, causing a selective sweep of alleles underlying the mimetic phenotype. Results from this study and previous work (Mullen 2006; Mullen et al. 2008; Prudic & Oliver 2008) support the following history for wing pattern evolution in the L. arthemis complex. First, the ancestral white-banded form gave rise to a mimetic lineage because of strong selection in the range of the codistributed model, B. philenor. Pleistocene vicariance of the mimetic lineage gave rise to allopatric populations of mimetic L. a. arizonensis in southwestern North America and mimetic L. a. astyanax in the southeast. Subsequently, hybridization between white-banded and mimetic populations would have resulted in sympatric mimetic forms fixed for different mtDNA haplotypes (e.g. IB and II) because of selection for the mimicry phenotype in the range of the model (figure 3). Non-mimetic populations of L. a. arthemis could have persisted in northwestern refugia, corresponding to mitochondrial haplotype IA, and expanded their range to give rise to the current zone of secondary hybridization between the two wing pattern phenotypes. Indeed, a history of episodic contact between mimetic and non-mimetic lineages is highly consistent with both the findings presented by Mullen et al. (2008) and Prudic & Oliver (2008), and also explains how mimetic phenotypes at the range limit of the model often possess non-mimetic mitochondrial haplotypes, as well as the lack of genealogical exclusivity for each phenotype and the highly asymmetrical gene flow between these two forms (L. a. astyanax→L. a. arthemis; Mullen et al. 2008). Ultimately, conclusive resolution of the history of wing pattern evolution in this group will almost certainly require identification of the specific locus/loci underlying the trait for mimicry.

Figure 3.

Scenario depicting the evolution of mimicry in the L. arthemis complex. A white-banded phenotype (ancestral state) gave rise to forms that evolved mimetic phenotypes when sympatric with a chemically defended species (B. philenor). Codistributed white-banded and mimetic phenotypes hybridized, resulting in the sweep of mimetic alleles into the white-banded form, and subsequently the capture of white-banded mitochondria (haplotype IB, blue circles) in mimetic forms that are sympatric with L. a. astyanax (haplotype II). Mimetic phenotypes are not recovered in other white-banded populations of L. a. arthemis (haplotypes IA, IC and ID). Limenitis a. arizonensis is allopatric with respect to L. a. astyanax and L. a. arthemis, and possesses an exclusive mtDNA haplotype (III). (Inferred from results in Mullen et al. 2008.)

(a) The causes and consequences of allopatric Batesian mimicry

Given the dramatic potential consequences of frequency-dependent selection on Batesian mimicry phenotypes with respect to both individual fitness and the potential origin of reproductive barriers among populations, it is essential to understand the conditions under which mimicry is expected to evolve and be maintained. Here, we focused on elucidating the evolutionary origins and fate of a Batesian mimetic phenotype among hybridizing populations of the L. arthemis butterfly species complex, and provided compelling evidence against an evolutionary loss of mimicry by reversion to the ancestral phenotype in this system. Batesian mimicry is a classic example of adaptive phenotypic evolution but, as yet, we have only an incomplete understanding of the conditions that maintain or break down the mimetic relationship between palatable Batesian mimics and unpalatable models. This is particularly true with respect to allopatric Batesian mimics that exist outside the geographical range of their respective models (Fisher 1930; Harper & Pfennig 2007, 2008; Pfennig et al. 2007). Specifically, it is unclear to what extent allopatric mimicry exists across diverse taxonomic groups, and how often allopatric mimics arise as a result of range expansion, range contraction of the model and/or through gene flow into non-mimetic populations.

The results of this study mean that we still have no unequivocal example of the loss of mimicry in natural populations (but see Harper & Pfennig 2008; reviewed in Joron 2008), and although it may well occur, results from a comprehensive analysis of mimicry evolution in Papilio butterflies strongly indicate otherwise (Kunte in review). Our results also caution against inferring character evolution using gene trees for recently diverged taxa, which are unlikely to resolve the true species phylogeny. Although recent advances in Bayesian and coalescent methodologies have improved our ability to recover phylogenetic relationships among closely related taxa with incongruent gene trees (Edwards & Beerli 2000; Maddison & Knowles 2006; Edwards et al. 2007; Liu & Pearl 2007), it is still true that gene trees and species trees are often not the same (Pamilo & Nei 1988; Maddison 1997; Edwards & Beerli 2000; Nichols 2001).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to B. Evans, S.-P. Quek and M. Kronforst for their technical and laboratory assistance. D. W. Pfennig, M. Kronforst, M. Hassel and three anonymous reviewers offered detailed comments and suggestions that greatly improved the manuscript. Part of this work was carried out by using the resources of the Computational Biology Service Unit from Cornell University, which is partially funded by Microsoft Corporation.

References

- Albertson R.C., Markert J.A., Danley P.D., Kocher T.D. Phylogeny of a rapidly evolving clade: the cichlid fishes of Lake Malawi, East Africa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:5107–5110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5107. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.9.5107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allender C.J., Seehausen O., Knight M.E., Turner G.F., Maclean N. Divergent selection during speciation of Lake Malawi cichlid fishes inferred from parallel radiations in nuptial coloration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:14074–14079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2332665100. doi:10.1073/pnas.2332665100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althoff D.M., Gitzendanner M.A., Segraves K.A. The utility of amplified fragment length polymorphisms in phylogenetics: a comparison of homology within and between genomes. Syst. Biol. 2007;56:477–484. doi: 10.1080/10635150701427077. doi:10.1080/10635150701427077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson T.M., et al. Molecular and evolutionary history of melanism in North American gray wolves. Science. 2009;323:1339–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.1165448. doi:10.1126/science.1165448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala F.J., Campbell C.A. Frequency-dependent selection. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1974;5:115–138. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.05.110174.000555 [Google Scholar]

- Baayen R.P., O'Donnell K., Bonants P.J.M., Cigelnik E., Kroon L., Roebroeck E.J.A., Waalwijk C. Gene genealogies and AFLP analyses in the Fusarium oxysporum complex identify monophyletic and nonmonophyletic formae speciales causing wilt and rot disease. Phytopathology. 2000;90:891–900. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2000.90.8.891. doi:10.1094/PHYTO.2000.90.8.891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkeren G., Kronstad J.W., Levesque C.A. Comparison of AFLP fingerprints and ITS sequences as phylogenetic markers in Ustilaginomycetes. Mycologia. 2000;92:510–521. doi:10.2307/3761510 [Google Scholar]

- Ballard J.W.O., Whitlock M.C. The incomplete natural history of mitochondria. Mol. Ecol. 2004;13:729–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.02063.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.02063.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton N.H., Hewitt G.M. Analysis of hybrid zones. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1985;16:113–148. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.16.110185.000553 [Google Scholar]

- Bates H.W. Contributions to an insect fauna of the Amazon valley (Lepidoptera: heliconidae) Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 1862;23:495. [Google Scholar]

- Bonin, A., Pompanon, F. & Taberlet, P. 2005 Use of amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers in surveys of vertebrate diversity. In Methods in enzymology, vol. 395 (eds E. A. Zimmer & E. H. Roalson), pp. 145–161. New York, NY: Academic Press. (doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(05)95010-6) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brouat C., Mckey D., Douzery E.J.P. Differentiation in a geographical mosaic of plants coevolving with ants: phylogeny of the Leonardoxa africana complex (Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae) using amplified fragment length polymorphism markers. Mol. Ecol. 2004;13:1157–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02113.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower J.V.Z. Experimental studies of mimicry. IV. The reactions of starlings to different proportions of models and mimics. Am. Nat. 1960;94:271. doi:10.1086/282128 [Google Scholar]

- Brower L.P., Brower J.V.Z. The relative abundance of model and mimic butterflies in natural populations of the Battus philenor mimicry complex. Ecology. 1962;43:154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Buntjer J.B., Otsen M., Nijman I.J., Kuiper M.T.R., Lenstra J.A. Phylogeny of bovine species based on AFLP fingerprinting. Heredity. 2002;88:46–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800007. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Després L., Gielly L., Redoutet B., Taberlet P. Using AFLP to resolve phylogenetic relationships in a morphologically diversified plant species complex when nuclear and chloroplast sequences fail to reveal variability. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003;27:185–196. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(02)00445-1. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00445-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S.V., Beerli P. Perspective: gene divergence, population divergence, and the variance in coalescence time in phylogeographic studies. Evolution. 2000;54:1839–1854. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb01231.x. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb01231.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S.V., Liu L., Pearl D.K. High-resolution species trees without concatination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:5936–5941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607004104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607004104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R.A. Clarendon Press; Oxford, UK: 1930. The genetical theory of natural selection. [Google Scholar]

- Funk D.J., Omland K.E. Species-level paraphyly and polyphyly: frequency, causes, and consequences, with insights from animal mitochondrial DNA. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003;34:397–423. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132421 [Google Scholar]

- Ganter P.F., Lopes M.D. The use of anonymous DNA markers in assessing worldwide relatedness in the yeast species Pichia kluyveri Bedford and Kudrjavzev. Can. J. Microbiol. 2000;46:967–980. doi: 10.1139/w00-092. doi:10.1139/cjm-46-11-967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A., Rubin D.B. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Stat. Sci. 1992;7:457–472. doi:10.1214/ss/1177011136 [Google Scholar]

- Getty T. Discriminability and the sigmoid functional response: how optimal foragers could stabilize model–mimic complexes. Am. Nat. 1985;125:239–256. doi:10.1086/284339 [Google Scholar]

- Giannasi N., Thorpe R.S., Malhotra A. The use of amplified fragment length polymorphism in determining species trees at fine taxonomic levels: analysis of a medically important snake, Trimeresurus albolabris. Mol. Ecol. 2001;10:419–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01220.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01220.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper G.R., Pfennig D.W. Mimicry on the edge: why do mimics vary in resemblance to their model in different parts of their geographical range? Proc. R. Soc. B. 2007;274:1955–1961. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0558. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper G.R., Pfennig D.W. Selection overrides gene flow to break down maladaptive mimicry. Nature. 2008;451:1103–1106. doi: 10.1038/nature06532. doi:10.1038/nature06532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodkinson T.R., Renvoize S.A., Ni Chonghaile G., Stapleton C.M.A., Chase M.W. A comparison of ITS nuclear rDNA sequence data and AFLP markers for phylogenetic studies in Phyllostachys (Bambusoideae, Poaceae) J. Plant Res. 2000;113:259–269. doi:10.1007/PL00013936 [Google Scholar]

- Holland B., Clarke A., Meudt H. Optimizing automated AFLP scoring parameters to improve phylogenetic resolution. Syst. Biol. 2008;57:347–366. doi: 10.1080/10635150802044037. doi:10.1080/10635150802044037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huheey J.E. Studies of warning coloration and mimicry. IV. A mathematical model of model–mimic frequencies. Ecology. 1964;45:185–188. doi:10.2307/1937125 [Google Scholar]

- Huheey J.E. Studies in warning coloration and mimicry. VII. Evolutionary consequences of a Batesian-Müllerian spectrum: a model for Müllerian mimicry. Evolution. 1976;30:86–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1976.tb00884.x. doi:10.2307/2407675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huheey J.E. Mathematical models of mimicry. Am. Nat. 1988;131:S22. doi:10.1086/284765 [Google Scholar]

- Joron M. Batesian mimicry: can a leopard change its spots—and get them back? Curr. Biol. 2008;18:R476–R479. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.009. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardolus J.P., Van Eck H.J., Van den Berg R.G. The potential of AFLPs in biosystematics: a first application in Solanum taxonomy (Solanaceae) Plant Syst. Evol. 1998;210:87–103. doi:10.1007/BF00984729 [Google Scholar]

- Koopman W.J.M., et al. AFLP markers as a tool to reconstruct complex relationships: a case study in Rosa (Rosaceae) Am. J. Bot. 2008;95:353–366. doi: 10.3732/ajb.95.3.353. doi:10.3732/ajb.95.3.353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krosby M., Rohwer S. A 2000 km genetic wake yields evidence for northern glacial refugia and hybrid zone movement in a pair of songbirds. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2009;276:615–621. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1310. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunte, K. In review. The diversity and evolution of Batesian mimciry in Papilio swallowtail butterflies. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lindström L., Alatalo R.V., Lyytinen A., Mappes J. The effect of alternative prey on the dynamics of imperfect Batesian and Müllerian mimicries. Evolution. 2004;58:1294–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb01708.x. doi:10.1554/03-271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Pearl D.K. Species trees from gene trees: reconstructing Bayesian posterior distributions of a species phylogeny using estimated gene tree distributions. Syst. Biol. 2007;56:504–514. doi: 10.1080/10635150701429982. doi:10.1080/10635150701429982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R., Hipp A.L., Larget B. A Bayesian model of AFLP marker evolution and phylogenetic inference. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2007;6:1–32. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1152. doi:10.2202/1544-6115.1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison W.P. Gene trees in species trees. Syst. Biol. 1997;46:523–536. doi:10.2307/2413694 [Google Scholar]

- Maddison W., Knowles L. Inferring phylogeny despite incomplete lineage sorting. Syst. Biol. 2006;55:21–30. doi: 10.1080/10635150500354928. doi:10.1080/10635150500354928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet J., Joron M. Evolution of diversity in warning color and mimicry: polymorphisms, shifting balance, and speciation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1999;30:201–233. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.30.1.201 [Google Scholar]

- Mappes J., Marples N., Endler J.A. The complex business of survival by aposematism. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005;20:598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.07.011. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson T.C., Shaw K.L. Rapid speciation in an arthropod: the likely force behind an explosion of new Hawaiian cricket species revealed. Nature. 2005;433:375–376. doi: 10.1038/433375a. doi:10.1038/433375a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, T. C., Shaw, K. L., Elizabeth, A. Z. & Eric, H. R. 2005 Use of AFLP markers in surveys of arthropod diversity. In Methods in Enzymology, vol. 395 (eds E. A. Zimmer & E. Roalson), pp. 161–177. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. (doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(05)95011-8) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Meudt H.M., Clarke A.C. Almost forgotten or latest practice? AFLP applications, analyses and advances. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.02.001. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen S.P. Wing pattern evolution and the origins of mimicry among North American Admiral butterflies (Nymphalidae: Limenitis) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2006;39:747–758. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.021. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen S.P., Dopman E.B., Harrison R.G. Hybrid zone origins, species boundaries, and the evolution of wing-pattern diversity in a polytypic species complex of North American admiral butterflies (Nymphalidae: Limenitis) Evolution. 2008;62:1400–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00366.x. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00366.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M., Li W.H. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:5269–5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols R. Gene trees and species trees are not the same. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001;16:358–364. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(01)02203-0. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02203-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonacs P. Foraging in a dynamic mimicry complex. Am. Nat. 1985;126:165–180. doi:10.1086/284407 [Google Scholar]

- Oaten A., Pearce C.E.M., Smyth M.E.B. Batesian mimicry and signal detection theory. Bull. Math. Biol. 1975;37:367–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02459520. doi:10.1007/BF02459520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamilo P., Nei M. Relationships between gene trees and species trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1988;5:568–583. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons Y.M., Shaw K.L. Species boundaries and genetic diversity among Hawaiian crickets of the genus Laupala identified using amplified fragment length polymorphism. Mol. Ecol. 2001;10:1765–1772. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01318.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01318.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfennig D.W., Harcombe W.R., Pfennig K.S. Frequency-dependent Batesian mimicry. Nature. 2001;410:323–323. doi: 10.1038/35066628. doi:10.1038/35066628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfennig D., Harper G., Brumo A., Harcombe W., Pfennig K. Population differences in predation on Batesian mimics in allopatry with their model: selection against mimics is strongest when they are common. Behav. Ecol. Sociol. 2007;61:505–511. doi:10.1007/s00265-006-0278-x [Google Scholar]

- Platt A.P. Monomorphic mimicry in Nearctic Limenitis butterflies: experimental hybridization of the L. arthemis-astyanax complex with L. archippus. Evolution. 1975;29:120–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1975.tb00820.x. doi:10.2307/2407146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt A.P., Coppinger R.P., Brower L.P. Demonstration of the selective advantage of mimetic Limenitis butterflies presented to caged avian predators. Evolution. 1971;25:692–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1971.tb01927.x. doi:10.2307/2406950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudic K.L., Oliver J.C. Once a Batesian mimic, not always a Batesian mimic: mimic reverts back to ancestral phenotype when the model is absent. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2008;275:1125–1132. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1766. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries L., Mullen S.P. A rare model limits the distribution of its more common mimic: a twist on frequency-dependent Batesian mimicry. Evolution. 2008;62:1798–1803. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00401.x. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00401.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritland D.B., Brower L.P. Mimicry-related variation in wing color of viceroy butterflies (Limenitis archippus): a test of the model-switching hypothesis (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) Hol. Lepid. 2000;7:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J.P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J.P., Van der Mark P. School of Computational Science, Florida State University; Tallahassee, FL: 2005. MrBayes 3.1 manual. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland H.M., Ihalainen E., Lindstrom L., Mappes J., Speed M.P. Co-mimics have a mutualistic relationship despite unequal defences. Nature. 2007;448:64–67. doi: 10.1038/nature05899. doi:10.1038/nature05899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruxton G.D., Sherratt T.N., Speed M.P. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2004. Avoiding attack: the evolutionary ecology of crypsis, warning signals and mimicry. [Google Scholar]

- Scott J.A. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1986. The butterflies of North America: a natural history and field guide. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw K.L. Conflict between nuclear and mitochondrial DNA phylogenies of a recent radiation: what mtDNA reveals and conceals about modes of speciation in Hawaiian crickets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16 122–16 127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242585899. doi:10.1073/pnas.242585899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan J.P., Lavoué S., Arnegard M.E., Hopkins C.D. AFLPs resolve phylogeny and reveal mitochondrial introgression within a species flock of African electric fish (Mormyroidea: Teleostei) Evolution. 2004;58:825–841. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00415.x. doi:10.1554/03-313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2000. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (PAUP 4.0* b10) [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk L.W.D., Van Ginkel M.V., Kik C. Phylogeny reconstruction and hybrid analysis in Allium subgenus Rhizirideum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000;100:1000–1009. doi:10.1007/s001220051381 [Google Scholar]

- Vekemans, X. 2002 AFLP-SURV version 1.0. Distributed by the author, Laboratoire Génétique et Ecologie Végétale, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium.

- Vos P., et al. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic. Acids Res. 1995;23:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. doi:10.1093/nar/23.21.4407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldbauer G.P. Asynchrony between Batesian mimics and their models. Am. Nat. 1988;131:S103. doi:10.1086/284768 [Google Scholar]

- Waldbauer G.P., Sternburg J.G. Experimental field demonstration that two aposematic butterfly color patterns do not confer protection against birds in Northern Michigan. Am. Mid. Nat. 1987;118:145–152. doi:10.2307/2425637 [Google Scholar]

- Wallace A.R. MacMillan Press; London, UK: 1870. Contributions to the theory of natural selection. [Google Scholar]

- Zhivotovsky L.A. Estimating population structure in diploids with multilocus dominant DNA markers. Mol. Ecol. 1999;8:907–913. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00620.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00620.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]