Abstract

Giant lipomas of the thenar are rare tumours of the adipose tissue of the hand, with a benign prognosis. Apart from the cosmetic problems they may cause, their most frequent complications include a compromise in functionality and pressure upon the nerves, mainly on the radial nerve. The first step in their management is their differential diagnosis from well-differentiated liposarcomas (WDLPS), as they require a different therapeutic approach. This step is completed with the aid of MRIs, biopsies and modern immunohistochemical methods, which offer high specificity and sensitivity. Our paper presents a case of giant lipoma of the thenar, with a review of the relevant literature, focusing on the disease’s molecular genetics, which is a very important field of research today.

Keywords: Giant lipoma, Thenar, Well-differentiated liposarcomas, Cytogenetics

Introduction

Lipomas are benign tumours of mesenchymatic origin, formed by mature adipocytes [1]. Described by Boyd as “amongst the most benign tumours” [3], they may appear in almost any human organ. Their presence in the hand represents 15% of soft-tissue tumours in the whole body. Despite this, international literature presents very few references to isolated cases, while only a small number of these concerns giant lipomas in this specific site [1, 4, 13]. We present a case of a giant lipoma of the thenar, its diagnostic and therapeutic approach, as well as the new prevalent theories in their aetiopathogenicity, as we believe that, even today, there are unexplored issues pertaining to their appearance.

Case Report

A 60-year-old woman weighing 79 kg visited the Outpatient Surgery of the Orthopaedic Unit due to progressive intumescence of the left hand, which first appeared a year ago. The patient did not report any past injuries or exulcerations at this site. She felt mild pain in this area, which aggravated when she tried to hold objects. The ability to grip was reduced in the affected limb. The physical examination revealed a large mass in the area of the thenar, extending from the second and third metacarpus. The mass was stable and painless upon palpation. The woman presented numbness and hypoesthesia in the radial section of the thumb.

Simple X-ray examination was not conclusive, so was followed by CT (Fig. 1) and MRI scans (Fig. 2), which revealed a 4.5 × 4.5 × 3-cm giant intramuscular lipoma with lobate and irregular borders, extending forwards between the first and second metacarpus and backwards from along the second and third metacarpus, without calcification and ossification points or bone infiltration. Subsequently, the mass was removed surgically through palmar access, with a 3.5-cm section at the level of the “life line” (Fig. 3). The mass was removed unimpaired and was sent for biopsy. The histological diagnosis was a lipoma (Fig. 4).

Figure 1.

The CT shows the characteristic radiolucency of the mature fat without any calcinosis or ossification of the tumour.

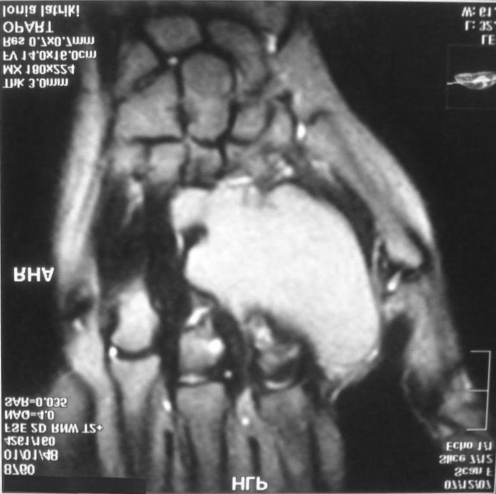

Figure 2.

The MRI shows that the tumour is independent of the first and second metacarpals and the periosteum of these bones is normal.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative photo showing the giant lipomatous mass of 4.5 × 4.5 × 3 cm.

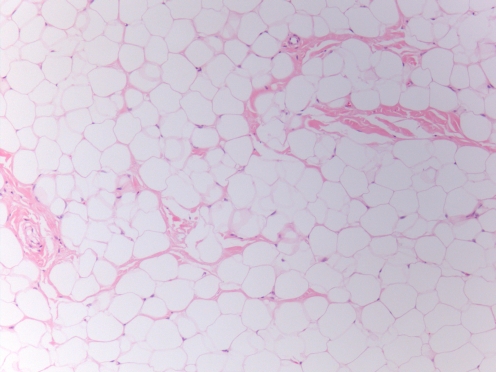

Figure 4.

Histological picture that reveals a well-differentiated mature adipose tissue with no evidence of any malignancy.

No complications appeared post-operatively. The pain, numbness and hypoesthesia gradually abated during the first month, while gripping ability was fully restored after approximately 1 year.

Discussion

Palm tumours are rare, while 50–70% of these are ganglion cysts. A smaller percentage corresponds to tumours originating from adipocytes, such as lipomas, adipofibrosis, angiolipomas, lipoblastomas and fibro-fatty hamartoma [6].

Lipomas are benign tumours caused by apidocyte proliferation, may be located on the hand or in any other part of the body and usually originate in the subcutaneous fat. Less frequently, their origin may be submuscular, as, for example, in the muscles of the thenar and subthenar, where diagnosis through physical examination plays a more limited role. They may also appear in deeper structures, such as in the carpal tunnel, Gayon’s tunnel or the deep palmar space [1, 4, 6, 13]. They may also appear in the bones, or even, in rare occasions, in the nerves. In specific, English-language literature reports only 39 cases in the peripheral nerves, 37 of which concern the median nerve, one case the sciatic nerve and one case the thumb’s digital nerve [11].

The aetiology behind the appearance of lipomas remains unclear, while their formation mechanism is unknown to date. Incretogenous, inflammatory and genetic disorders have been incriminated as causative factors. Obesity and hypercholesteraemia have been linked to the creation of lipomas, while trauma has also been included in their aetiological factors. It has been described that the necrosis of the fatty tissue and the presence of large and severe haematomas may lead to the stimulation of pre-adipocytes and the formation of lipomas [15].

Recently, many cytogenetic studies have been realised on tumours originating from adipocytes. This tumour category includes benign lipomas, as well as malignant WDLPS: well-differentiated liposarcomas. Both the above histological types consist of mature adipocytes and may be difficult to differentiate through simple inspection. The majority of the said tumours present genetic mutations in chromosomal region 12q13–15, presenting, however, some important differences. Lipomas present simple structural disorders, which mainly concern regions 12q13–15 and 6p 13q and are usually translocations or inversions that lead to the fusion of gene HMGA2 with various partners. HMGs (High Mobility Group) proteins are a class of relatively small non-histonic nuclear proteins that link to the DNA and act as regulatory transcription factors, acting on the organisation of chromatin at the moment of DNA transcription. The most common translocation is t(3;12)(q27–q28;q13–q15), which corresponds to 25% of the specific cytogenetic group. In addition, we often see disorders caused by chromosome 13, which account for 15–20% of all lipomas.

On the contrary, WDLPS, which are also called “atypical lipomatous tumors” are noted by the presence of a supernumerary ring or giant chromosome with amplified material from chromosome 12q14–15. The gene that plays an important role in this specific case is MDM2, which is located in 12q15, far from HMGA2. Its action is co-amplified by neighbouring genes, such as CDK4 and, less frequently, by SAS/TSPAN31 and HMGA2 [2, 7, 10, 12, 16, 17].

Intermuscular and intramuscular lipomas are very rare and form just 1% of lipomas. Any soft-tissue mass larger than 5 cm should be regarded as malignant until proof to the contrary [5]. The correct differential diagnosis between deep lipomas and WDLPS is extremely important to permit appropriate monitoring and treatment. An important role in this case may also be played by modern immunochemical methods that detect the expression of MDM2 and CDK4 and offer high specificity and sensitivity.

Clinically, they may reach a large size and supersede but not infiltrate neighbouring tissues. The main problems they can cause include the compromised functionality of the upper limb, mainly as regards its motion range and gripping ability. Another important problem they may cause involves the compression of certain nerves. Although these problems have been reported, they are not common. More frequently, they affect the radial nerve and less so the median nerve. A full recovery can be achieved gradually, after removal of the tumour [4, 8].

At the moment, MRI is the most reliable imaging method to diagnose lipomas. Τ1-weighted images show high signal intensity in a well-defined encapsulated even soft-tissue mass [4, 19]. An image, however, with infiltration of the neighbouring tissues raises suspicion of a liposarcomas. X-rays and CT scans are useful in the rare cases of tumour calcifications or ossifications, as MRIs frequently fail to detect them [9, 14, 18]. The histological identification of the tumour through biopsy is regarded by many researchers as necessary only in cases where no diagnosis is achieved through the MRI. In addition, numerous reports state that the degree of the tumour’s evenness in the MRI may allow for an evaluation of the risk of regression. The larger the unevenness, the higher the risk of regression [13]. Despite this, biopsies in the case of giant lipomas are deemed necessary for their differentiation from liposarcomas [4].

These lipomas are treatment by surgical removal. As the frequency of malignant transformation is extremely limited, the main reason for their removal is the disturbance they cause in the palm’s functionality and cosmetic appearance [8]. Regressions are extremely rare and are usually caused by the defective excision of the tumour [4]. Surgical risks mainly concern port-operative infection, neural damage and the formation of a painful exuvia [13].

In conclusion, giant lipomas of the thenar are rare benign tumours with an excellent prognosis after successful excision and a very limited risk of transformation. They do however require a careful diagnostic approach to differentiate them from WDLPS, which, even in their aggressive from, may present histologically benign regions. MRIs and immunochemical methods can help us in an accurate diagnosis, which is directly linked to the efficient management of the tumour.

Footnotes

No funds were received in support of this work. No benefits of any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Aust MC, Spies M, Kall S, Jokuszies A, Gohritz A. Posttraumatic lipoma: fact or fiction. SKINmed Dermatol Clinician 2007;6:266–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Cribb GI, Cool WP, Ford DJ, Mangham DC. Giant lipomatous tumors of the hand and forearm. J Hand Surgery (British and European Volume). 1993;30(5):509–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Dei Tos AP, Cin PD. The role of cytogenetics in the classification of soft tissue tumors. Virchows Arch 1997. 431:83–4. doi:10.1007/s004280050073. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Higgs PE, Young VL, Schuster R, Weeks PM. Giant lipomas of the hand and forearm. South Med J 1993. 86(8):887–90. doi:10.1097/00007611-199308000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hsu CS, Hentz VR, Yao J. Tumors of the hand. Lancet Oncol 2007. 8:157–6. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70035-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ingari JV, Faillace JJ. Benign tumors of fibrous tissue and adipose tissue in the hand. Hand Clin 2004. 20:243–8. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Italiano A, Cardot N, Dupre F, Monticelli I, Keslair F, Piche M, et al. Gains and complex rearrangement of the 12q13–15 chromosomal region in ordinary lipomas: the “missing link” between lipomas and liposarcomas. Int J Cancer 2007. 121:308–15. doi:10.1002/ijc.22685. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Johnson CJ, Pynsent PB, Grimer RJ. Clinical features of soft tissue sarcomas. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2001;83:203–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Matsui Y, Hasegawa T, Kubo T, Goto T, Endo K, Bando Y, Yasui N. Intrapatellar tendon lipoma with chondro-osseous differentiation: detection of HMGA2-LPP fusion gene transcript. J Clin Pathol 2006. 59:434–36. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.026393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Matsuo T, Sugita T, Shimose S, Kubo T, Yasumaga Y, Ochi M. Intraneural lipoma of the posterior interosseous nerve. J Hand Surg [Am] 2007. 32A(10):1530–32. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Narvaez JA, Narvaez J, Aguillera C, De Lama E, Portabella F. MR imaging of synovial tumors and tumor-like lesions. Eur Radiol 2001. 11:2549–60. doi:10.1007/s003300000759. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Pedeutour F, Fo C, et al. De la cytogenetique a la cytogenomique des tumeurs adipocytairea: 1 Tumeurs adipocytaires benignes. Bull Cancer 2002;89(7):689–5. [PubMed]

- 13.Regan JM, Bickel WH, Broders AC. Infiltrating lipomas of the extremities. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1946;54:87–3. [PubMed]

- 14.Sandberg AA. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular genetics of bone and soft tissue tumors: lipoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2004. 150:93–115. doi:10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Schrofft H, Hager D, Dunst KM, Huemer GM. Giant lipoma of the thenar. Images in Clin Med 2007;119(5–6):149. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Tallini G, Cin PD, Rhoden KJ, Chiapetta G, et al. Expression of HMGI-C and HMGI(Y) in ordinary lipoma and atypical lipomatous tumors. Immunohistochemical reactivity correlates with karyotypic alterations. Am J Pathol 1997;151(1):37–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Val-Bernal JF, Val D, Garijo MF, Vega A, Gonzalez-Vela MC. Subcutaneous ossifying lipoma: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol 2007. 34:788–92. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Willen H, Akerman M, Dal Cin P, De Wever I, Fletcher CDM, et al. Comparison of chromosomal patterns with clinical features of 165 lipoma: a report of the CHAMP study group. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1998. 102:46–9. doi:10.1016/S0165-4608(97)00292-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Yang T-H, Fong Y-C, Hsu H-C, Jim Y-F, Chiang I-P, Lin M-J. Ossifying lipoma of the hand. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2008. 33:82–3. doi:10.1177/1753193407087863. [DOI] [PubMed]