Abstract

Purpose

The management of open fractures of the tibia in a pediatric population represents a challenge to the clinician. Several case series over the course of many years have been performed describing the results of treating these injuries. It remains unclear, however, whether there is a preferred modality of treatment for these injuries, if a more severe injury confers a greater risk of infection, and if time to union is affected by Gustilo type, although trends seem to exist. The purpose of this study was to assemble the available data to determine (1) the risk of infection and time to union of various subtypes of open tibia fractures in children and (2) the changes in treatment pattern over the past three decades.

Methods

A systematic review of the available literature was performed. Frequency weighted mean union times were used to compare union times for different types of open fractures. Mantel Haentzel cumulative odds ratios were used to compare infection risk between different types of open fractures. Linear regression by year was used to determine treatment practices over time.

Results

No significant change in practice patterns was found for type I and III fractures, although type II fractures were more likely to be treated closed in the later years of the study compared to the earlier years. Type III fractures conferred a 3.5- and 2.3-fold greater odds of infection than type I and type II fractures, respectively. There was no significant difference in odds of infection between type I and II fractures. There was a significant delay in mean time to union between type I and type II fractures, and between type II and type III fractures.

Conclusions

With the exception of type II fractures, the philosophy of treatment of open fractures of the tibia has not significantly changed over the past three decades. Closed treatment or internal fixation are both viable options for type II fractures based on their relatively low incidence of infection. This study also demonstrates a strong relationship between Gustillo sub-types and odds of infection in this population. Not surprisingly, union rates are also delayed with increasing injury severity.

Keywords: Children, Infection, Open tibia fracture(s), Pediatric, Systematic review, Time to union

Introduction

The management of open fractures of the tibia in the pediatric population is a challenging problem. Traditional methods of managing these fractures, such as closed treatment with plaster casts, have evolved from open irrigation and debridement, casting, either isolated or with pins and plaster and, more recently, external or internal fixation methods. Internal fixation, especially with intramedullary devices, is an emerging technique that has rapidly gained popularity over the past decade.

The biology of these fractures in children differs notably from that in adults due to the presence of a thick periosteum, of better vascularity, better healing ability, and improved potential to remodel. These characteristics have long provided surgeons with the option to manage these fractures by irrigation and debridement followed by casting. Interestingly, the changing pattern of injuries with progressive urbanization, the increasing social demand on children to return early to active athletics and sports, and pressure from parents and family for the clinician to obtain early, fast, and perfect results could potentially bias clinicians towards operative fixation of these fractures in some cases.

Advances in knowledge in the areas of bacteriology and microbiology, antibiotics, and wound care have propagated a current era of thorough debridement under anesthesia with wound irrigation and antibiotics. While patients are under anesthesia, the clinician can easily be convinced to opt for some sort of operative stabilization (either with internal or external fixation) if moderate or severe soft tissue injuries are present.

Open fractures of the tibia in a pediatric population can be associated with notable morbidity, including but not limited to compartment syndrome, deep infection, non union, and even amputation [1–14]. Although some clinicians purport that these injuries may behave similarly in children and adults, others feel that these injuries are better tolerated in children, particularly young children [9]. Most of the available literature seems to indicate that higher Gustillo type fractures (in adults and children) tend to have more complications and less predictable outcomes [1–14]. However, many of these studies have low numbers, and as such, it is difficult to show a statistically significant difference, even though one almost certainly exists.

Our study was carried out to answer the following questions: first, how has the treatment pattern for open fractures of the tibia evolved in a pediatric population (<18 years) during the past three decades based on their Gustilo types? second, what is the comparative risk of infection in different sub-types of open tibial fractures? third, is there any difference in time to fracture healing for different types of open tibia fractures in pediatric population?

Materials and methods

We searched the Medline, EMBASE, and Cochrane computerized literature databases from January 1980 to June 2008 for articles containing the following terms: open tibia fracture(s), children, treatment(s), and outcome(s). Reference lists from the articles retrieved were further scrutinized to identify any additional studies of interest. All studies from these searches were then reviewed. Studies were included in this systematic review if they matched the following criteria: (1) they were in English; (2) they had a level I, II, III, or IV study design by Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery criteria (because the majority of studies in clinical orthopedic literature are retrospective studies of level III or level IV evidence, and our goal was to be inclusive); (3) the series reported had a minimum of 15 open tibia fractures; (4) patients in the study had an open tibia fracture or closed fractures and non-tibia fractures could be easily separated in the body of the text; (5) all patients included in the study were <18 years old; (6) the minimum follow-up was 6 months. Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) closed fractures could not easily be separated from open fractures in the body of the text; (2) inadequate follow-up; (3) data were not categorized as open subtypes by the Gustilo and Anderson classification (Table 1); (4) more than one type of fracture was included (i.e. tibia and femur) and the tibia fractures could not easily be separated. Two authors performed the initial search (OB, KB), following which three of the authors (OB, KB, HH) independently reviewed the results and selected the appropriate studies based on the above criteria.

Table 1.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Type I | Clean wound <1 cm in diameter with simple fracture pattern and no skin crushing |

| Type II | A laceration >1 cm and <10 cm without significant soft tissue crushing. The wound bed may appear moderately contaminated |

| Type III | An open segmental fracture or a single fracture with extensive soft tissue injury >10 cm. Type III injuries are subdivided into three types |

| Type IIIA | Adequate soft tissue coverage of the fracture despite high energy trauma or extensive laceration or skin flaps |

| Type IIIB | Inadequate soft tissue coverage with periosteal stripping |

| Type IIIC | Any open fracture that is associated with vascular injury that requires repair |

We identified 61 articles from our search of the databases: 30 from PubMed [1, 11, 15–42], six from Cochrane [43–48], and 25 from EMBASE [4–7, 9, 11, 31, 37, 49–65]. Three of these studies were found in both the PubMed and EMBASE databases [11, 31, 37]. Twenty-two studies [21, 23, 24, 31–35, 38, 39, 41, 46, 51, 52, 54–56, 58–61, 64] were excluded because they reported closed tibia fractures exclusively or in addition to open tibia fractures, and not enough data was supplied to analyze the open tibia fractures separately. Fifteen studies [15, 17–19, 22, 25–30, 36, 40, 42, 48] were excluded because they included adults, and we were unable to separate the adult data from those of patients <18 years of age. Three papers [29, 37, 43] were excluded because they were review papers and not studies that included patient treatment and follow-up information. Three studies [50, 57, 62] were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria of having at least 15 patients in the study. The Dubar et al. [20], Morton et al. [45], and Rome et al. [47] studies were excluded from our review because these were protocol/technique papers that did not present patient data or follow-up. The Lobost et al. [53] study was excluded because fractures were treated solely with antibiotics, and no operative treatment occurred. Four studies [44, 50, 63, 65] were not included in our review because they included fractures other than open tibia fractures. A thorough review of the bibliographies of the remaining studies was carried out by all authors who selected articles that had the words: open, tibia, fracture(s), and children(s). Additional publications [2, 3, 8, 10, 12–14, 66, 67] were identified via this method, and the full text of each paper was subsequently reviewed to determine which studies met the inclusion criteria. Eight studies met our pre-determined inclusion criteria and were included in our systematic review. The Blaiser and Barnes [66] study was excluded from our systematic review because the authors did not break down fracture outcome by Gustillo type. We also excluded the Cramer et al. [67] study because the paper included fractures of the femur and presented the data in a way in which we could not extract or isolate data concerning tibia fractures. In contrast, the study of Robertson et al. [12] was included because the data were well separated, enabling the data pertaining to open tibia fractures to be extracted, and the remainder of our inclusion and exclusion criteria were satisfied. The Yasko paper [14], while having limited treatment data, was included in our study because after discussion among the four authors of this review, the consensus opinion was that this study had adequate data, satisfied all inclusion criteria, and met no exclusion criteria. This left 14 papers that met all of our inclusion criteria and none of our exclusion criteria [1–14].

There were a total of 726 open fractures of the tibia in patients younger than 18 years of age that met all of the inclusion criteria in the 14 studies. Table 2 summarizes the demographics of these studies. For studies that provided the ages of the pediatric patients (12 studies, n = 581), the weighted average age at time of injury was 9.3 years (range 2–18 years) [1–6, 8–13]. Gender information was provided for 675 patients (13 studies), of whom 173 (26%) were female and 502 (74%) were male [1–13]. There were 723 open tibia fractures that were classified by Gustillo type, of which 231 were type I fractures (31.9%), 267 were type II fractures (37.0%), and 225 were type III fractures (31.1%). Of the type III fractures, 209 were further subclassified into IIIA (108; 51.7%), IIIB (76; 36.4%), and IIIC (25; 12%). The presence of a fibula fracture was not routinely documented in the respective studies; for consistency, we therefore chose to eliminate this from the focus of the study. In those studies that had average follow-up information (nine studies, n = 435), the frequency weighted mean follow up was 18.9 months (range 1–150 months) [1–6, 9, 11–13]. Frequency weighted mean union (defined by clinical, radiological, or both criteria) rates for all tibia fractures was 14.6 weeks (range 9.1–21.0 weeks).

Table 2.

Demographics of studies meeting inclusion criteria

| Study authors | Year | Age, years (range) | Number of fractures | Female/male | Average follow-up, months (range) | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartlett et al. [1] | 1997 | 9 (3.5–14.5) | 23 | 5/18 | 34 (6–85) | IV |

| Buckley et al. [2] | 1990 | 9.8 (2.9–16.2) | 42 | 9/32 | 15 (3–96) | IV |

| Buckley et al. [3] | 1996 | 9.1 (2.9–16.2) | 20 | 4/16 | 20 (3–108) | IV |

| Cullen et al. [4] | 1996 | 9.0 (3.0–17.0) | 83 | 18/65 | 14 (2–75) | IV |

| Fujita et al. [5] | 2001 | 7.4 (4.0–13.0) | 16 | 3/13 | 48 (12–150) | IV |

| Grimard et al. [6] | 1996 | 10.6 (3.1–18.0) | 90 | 32/58 | 18 (2–100) | IV |

| Hope et al. [7] | 1992 | (3.1–16.0)a | 92 | 21/74 | Not mentioned | IV |

| Irwin et al. [8] | 1995 | 8 (3.2–15.0) | 58 | 26/32 | Not mentioned | IV |

| Jones et al. [9] | 2003 | 7.2 (2–12) | 83 | 21/62 | 7 (1–35) | IV |

| Kreder et al. [10] | 1995 | 10.0 (3.0–17.0) | 56 | 9/47 | Not mentioned | IV |

| Levy et al. [11] | 1997 | 10.1 (5.0–15.0) | 40 | 8/32 | 26 (18–84) | IV |

| Robertson et al. [12] | 1996 | 10.8 (5.0–15.0) | 32 | 7/25 | Not mentioned | IV |

| Song et al. [13] | 1996 | 11.0 (4.0–15.0) | 38 | 10/28 | 33 (9–122) | IV |

| Yasko et al. [14] | 1989 | 10.0b | 53 | N/A | Not mentioned | III |

aNo mean age given

bNo age range given

All fractures were managed with irrigation and debridement, and standard of care antibiotics. Three hundred and ninety-seven fractures were treated in a cast [1–14] or pins and plaster [6, 9] after irrigation and debridement, 198 were treated with external fixation only, 31 were treated with internal fixation alone, and one fracture was treated with both internal and external fixation. Nine fractures underwent amputation. For the remainder of the fractures, insufficient information was available to assess the modality of treatment. Data were provided on wound closure in 385 patients. Of these patients, 198 were closed primarily, 187 were closed after initially being left open or healed by secondary intention, and 109 required some type of soft tissue coverage. Information on the treatment of wounds was lacking for the remainder of the fractures. Practice patterns seem to indicate a willingness to close type I and type II fractures primarily, with 43.2 and 52.3% of these fractures types, respectively, closed primarily in the three studies that provided this information. In contrast, only 16.7% of type III fractures were closed primarily, Bartlett et al. [1] and Levy et al. [11] both performed either delayed primary closure after a second irrigation and debridement or a plastic surgical procedure (flap or graft) to close the wound.

Method of treatment was also considered in some studies based on the fracture type. One hundred and eleven type I fractures were treated with casting methods (a cast or pins and plaster following irrigation and debridement), 15 were treated with external fixation, and seven were treated with open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) techniques. Type II fractures were treated with casting methods in 125 cases, with external fixation in 48 cases and with ORIF in eight cases. Type III fractures were treated with casting methods in 40 cases, with external fixation in 94 cases and with ORIF in 13 cases. Table 3 summarizes the treatment patterns by Gustillo type. Not all studies specified treatment by type. There were very few studies that stratified infections by treatment type, although some infections (i.e., pin tract infections) were restricted to some treatment types (external fixation). Open reduction internal fixation was accomplished with Ender’s nails [2], dynamic compression plating [3, 13], interfragmentary screws or pins [4–6, 13], K wires [4, 5, 7, 10], or intramedullary nailing [4, 12]. Linear regression analysis was performed to determine if there was a trend in treatment pattern over time.

Table 3.

Definitive treatment modalities by the Gustillo type of open tibia fractures in children

| Gustillo type | Closed treatment (%)a | External fixation (%) | Open treatment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | 111 (83.5)a | 15 (11.3) | 7 (5.3) |

| Type II | 125 (69.1) | 48 (26.5) | 8 (4.4) |

| Type III (all) | 40 (27.2) | 94 (63.9) | 13 (8.8) |

| Type IIIA | 18 (29.5) | 36 (59.0) | 7 (11.5) |

| Type IIIB | 1 (2.9) | 31 (88.6) | 3 (8.6) |

| Type III C | 0 (0) | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) |

aIncludes casting or pins and plaster following irrigation and debridement

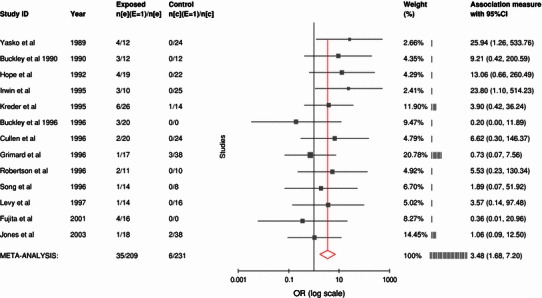

Fisher’s exact test was used to assess for the significance of differences between infection rates among the types of open fractures. A student’s t test using frequency weighted data, with equal variances not assumed, was used to compare union rates among different types of open fractures. A cumulative meta-analysis fixed effects model was then constructed with the Mantel Haenszel technique to describe the odds of infection by type of open fracture. Forrest plots were created to qualitatively assess for study heterogeneity (Fig. 1). Funnel plots were also created to assess for publication bias, and symmetric plots with no significant publication bias were found. We also regressed number of patients by year of publication to assess for publication bias by year; this regression found no significant publication bias by year (p = 0.898). Because the methods of each study were similar, and the populations were all children under the age of 18 years, we performed a fixed effects model. Meta-analytic statistics were calculated with MIX software (Kitasato Research Center, Sagamihara, Kanagawa, Japan) [68, 69], and other statistics were calculated with SPSS processor, ver. 15.0 (SPSS. Chicago, Il).

Fig. 1.

Representative Forrest plot for odds of infection in type III fractures compared to type I fractures, listed by year. CI Confidence interval, OR odds ratio

Results

Linear regression analysis revealed no significant changes in the treatment pattern of type I and type III fractures over time. Between 1989 and 2003 (the first study and the last study), there was an increasing trend to treat type II fractures by casting methods (p = 0.044) and a decreasing linear trend to treat type II fractures with an external fixator (p = 0.018), but there was no change in the percentage of patients treated by ORIF.

The overall infection rate for open tibia fractures in these studies ranged from 3.6 to 30.4%. Type I tibia fractures had low infection rates (6/231; 2.6%) for all infections, and no deep infections or osteomyelitis were reported. The superficial infection rate in type II tibia fractures was significantly higher than that in type I fractures (18/261; 6.9%; p = 0.0374) and non-significantly higher for deep infections or osteomyelitis (2/261; 0.8%; p = 0.501). The infection rate for all type III fractures was also significantly higher than that for type I fractures (34/208; 16.3%; p < 0.0001) and significantly higher for deep infections or osteomyelitis (15/208; 7.2%; p < 0.0001). In studies which reported infection rates for Gustillo type III subtypes, the infection rate for IIIA fractures for all infections was 5/81 (6.2%) and for deep infections, 2/81 (2.5%); for IIIB fractures, for all infections, 10/47 (21.3%), and for deep infections, 2/47 (4.2%); for IIIC fractures, for all infections, 7/20 (35%), and for deep infections, 3/20 (15%). One study had only type II and type III fractures and claimed no infections, but it did report a few “impending” infections which were treated with antibiotics and resolved; the specific types involved were not mentioned [1]. Two other studies had no type I or type II fractures [2, 5]. Of the remaining 11 studies, four reported a significant difference in infection rate in type III fractures compared to type I, and no study showed a significant difference between type I and type II fractures, or between type II and type III fractures [1, 3, 4, 6–14]. A cumulative fixed effects model was calculated using the Mantel Haenszel to determine cumulative odds of any infection by Gustillo type. The results are summarized in Table 4. Type III fractures were 3.48-fold more likely to have an infectious complication than type I fractures (p = 0.0008) and 2.28-fold more likely to have an infectious complication than type II fractures (p = 0.009). There was no statistically significant difference between type I and type II fractures in terms of overall infection rate (deep plus superficial). There was no specific temporal pattern to the infectious complications (Fig. 1).

Table 4.

Mantel Haenszel pooled cumulative odds ratios for risk of infection by fracture type

| Comparison | Mantel Haenszel odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p value | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds of infection in type II fracture compared to type I | 1.899 | 0.794, 4.540 | 0.149 | 8 |

| Odds of infection in type III fracture compared to type I | 3.482 | 1.682, 7.206 | 0.0008 | 13 |

| Odds of infection in type III fracture compared to type II | 2.284 | 1.224, 4.260 | 0.009 | 13 |

Studies were reviewed to determine which treatments were associated with higher rates of infection. Bartlett et al. [1] noted seven “impending” infections that were associated with external fixation; this was defined as erythema and drainage that resolved with local care. Buckley et al. [2, 3] found four pin tract infections, two deep infections, and four cases of osteomyelitis; all of these patients had been treated with external fixation. Cullen et al. [4] noted one patient who had pin tract drainage associated with an external fixator and one patient who had drainage with pin and screw fixation which resolved after removal of the pins. Fujita et al. [5] noted two superficial infections (one IIIA, one IIIB) and two cases of osteomyelitits (both IIIB); all patients had been initially treated with an external fixator. Grimard [6] noted six infections: three pin tract infections (all external fixation patients) and three superficial infections. Two of these patients were treated with external fixation with screws, and one was treated with external fixation. Both Irwin et al. [8] and Jones et al. [9] noted two pin tract infections associated with external fixation, with Irwin et al. noting one other superficial infection and three deep infections, which were not classified by treatment. Jones et al. noted two other superficial infections but did not mention the surgical stabilization treatment the patients had received. Kreder et al. [10] had six infections, with two of the deep infections treated with external fixation; this paper did not explicitly state what surgical stabilization the others had received. In the Robertson et al. [12] series, one girl had bilateral IIIC tibia fractures which necessitated amputation; these developed deep infections requiring several irrigation and debridements. In the Song et al. [13] series, there were six pin tract infections associated with external fixation. Only one case resulted in operative debridement, and three patients with deep infection all had internal fixation with DCP plates or lag screws. The remainder of the studies whose patients experienced infections, whether deep or superficial, provided insufficient information in the body of the paper to ascertain the treatment that was associated with the infection [7, 11, 14].

The frequency weighted time to mean union was 11.6 weeks [95% confidence interval (CI)11.3–12.0 weeks] for type I fractures and 13.5 weeks (95% CI 13.2–13.9 weeks) for type II fractures. This indicates a significant delay in the healing of type II fractures compared to type I fractures (p < 0.001). Type III fractures had a frequency weighted mean time to union time of 16.1 weeks (15.5–16.7 weeks), which represents a significant delay compared to both type I fractures (p < 0.001) and type II fractures (p < 0.001). When type III fractures were broken down into their subcategories, the frequency weighted mean time to union of IIIA fractures was 17.7 weeks (95% CI 16.5–18.9 weeks), that of type IIIB fractures was 27.6 weeks (95% CI 23.0–32.2), and that of type IIIC fractures was 33.7 weeks (95% CI 27.1–40.2 weeks). It should be noted, however, that 10/25 type IIIC fractures in these series were documented to have ended in amputation, so union rates only reflect fractures that did not end in amputation [2, 3, 6, 9, 10]. Of note, Bartlett et al. [1] seem to have removed all type I fractures (26 in total) from their study. The Hope et al. [7] study did not include in their statistical analysis three patients who eventually died. Cullen et al. [4] excluded nine patients due to reasons of inadequate follow-up, primary amputation, or death.

Discussion

The management of open fractures of the tibia in a pediatric population remains a complex and challenging problem. Traditionally, open tibia fractures in children have been managed with closed reduction and casting techniques following irrigation and debridement. With increasing advances in pediatric sedation and anesthesia, wound care and antibiotics and a large armamentarium available for both internal and external fixation of these fractures, one would think that the approach to treatment of these fractures would have trended towards fixation in more recent years. In reality, only type II fractures have seen a significant change in treatment pattern over the course of time, and the change has been increasingly to treat these fractures in a closed fashion (pins and plaster or casting after irrigation and debridement). Interestingly, data from several studies investigating open tibia fractures in children have low numbers and often do not have enough power to make meaningful conclusions.

This systematic review was performed to answer the following questions: how has the treatment pattern for open fractures of the tibia in children evolved during the past three decades based on their Gustilo types? What is the comparative risk of infection in different sub-types of open tibial fractures? Is there any difference in time required for fracture healing in different sub-types of open tibia fractures? Therefore, this systematic review represents a synthesis of the available data and provides the reader with valuable information that will likely help the clinician in decision-making and in setting family expectations.

As far as changing patterns of treatment are concerned, multiple speakers in sub-specialty meetings over recent years have suggested that there is a current trend towards changes in the fracture fixation of these fractures. However, based on the factual data reported in this study, we found that the reverse is true—at least for type II open tibia fractures. The treatment pattern of type I and III fractures has not significantly changed over the past two decades.

Although it may be intuitive that the infection rates are likely higher with increasing Gustilo class of injury, there has been a lack of adequately powered data to support this contention. We found in this systematic review that the odds of any type of infection were significantly greater in type III fractures than in type I and II fractures. Based on this study, the pooled data did not provide any evidence of a significant difference in infection rate between types I and II fractures. This result seems to support the trend observed in treating type II fractures by casting methods, following irrigation and debridement, which is similar to the typical approach used to treat type I fractures. An increasing trend in performing internal fixation of type II fractures for early mobilization and rapid healing could also then be justified in the current scenario, as there does not appear to be a higher likelihood of infection compared to type I injuries.

In this systematic review we have also attempted to provide objective data towards ‘fracture-healing time’ for different classes of open tibia fractures in children. The frequency weighted pooled mean time to union was 11.6 weeks for type I fractures, 13.5 weeks for type II, and 16.1 weeks for type III fractures. This result indicates a significantly longer time to union as the severity of the injury increases. Again, this may be intuitive to a certain extent, especially considering that the higher the Gustilo type, the worse the nature of bony and soft-tissue injury. However, having meaningful data from a larger number of cases certainly helps to enhance the evidence-based literature. Such data also helps set expectations for the treating clinician as well as the patient and the family members.

Current trends in clinical practices have demonstrated a somewhat paradigm shift in the treatment of tibial fractures in children, with some types of open fractures being treated on similar grounds as closed injuries. There is no question that various modalities of fixation, particularly internal fixation devices, are gradually making their way into the management of these fractures and that these are being used more now than a few decades ago. Although a certain degree of consensus seems to exist supporting irrigation and debridement in the operating room in open fractures of the tibia in children, there is still controversy in the literature regarding specific aspects of optimal surgical treatment in these fractures. The management of these fractures is likely to remain situational (based on patient circumstances, available healthcare resources and surgeon judgment) until good level I or II data are available. For the most part, huge changes in clinical practices are unlikely since the current treatment strategies seem to work well from the perspective of patient care.

A number of points become evident from this systematic review of the available literature. The increased rate of casting in the later years of this study did not result in an increased infection rate between type I and type II fractures. This suggests that casting following irrigation and debridement as a management modality for type I and II open fractures seems to give adequate and comparable results as far as soft-tissue healing and fracture healing is concerned—at least in terms of infectious complications. This evidence is probably more important in scenarios where healthcare systems may not be fortunate enough to have all of the resources available for advanced fixation techniques. In these situations, the clinicians need to understand that the timely and appropriate administration of antibiotics, irrigation and debridement of the wounds, gentle handling of soft-tissues, and appropriate wound dressings with casting (with or without cast windows as needed) may be all that is needed for fracture care and will give the child an equal opportunity for a good outcome in terms of infection control, healing (soft-tissues and fracture), and functional restoration.

The review of literature also seems to point out that external fixation is associated with a number of additional clinical problems, such as pin tract infections, when compared to other modalities of treatment. It is equally clear that severe injuries (IIIB and IIIC) are often not appropriate for casting, and in some of these cases, internal fixation may prove to be perilous as well. This seems to be the best case scenario for the usage of external fixation with delicate care of soft-tissues. In fact, all type III fractures in general could be lumped into a separate entity based on this systematic review in which the personality of soft-tissue damage requires a comprehensive and case-dependent strategy. Further studies are necessary to accurately define this relationship.

This study has a number of significant limitations. We did not have access to the raw data for each study, which in some ways limited our analysis. Specifically, we would have liked to have presented the results on infections rates in relation to the size of the wound, type of wound closure, and Gustillo type. Limitations in the manner the data of the individual studies were presented prevented us from doing so. Secondly, problems with inference, including bias, confounding, and random chance inherent to the individual observational studies utilized in this review are not improved by pooling the data. Third, we were not able to assess for malunion, as key information, such as presence or absence of a fibula fracture, radiographic information, or information regarding residual deformity, was absent. Fourth, ten of the 14 studies had patients older than 15 years, and there was no clear way to eliminate patients whose growth plate was closed in the absence of radiological data. In addition, some studies would have needed to be eliminated altogether because they lacked lists which would have allowed us to manually eliminate patients above a certain age if we lowered our age requirement. This would decrease the external validity of our study significantly; therefore, we had to select patients who might present to a pediatric hospital and use the age of 18 years as our limit as opposed to growth plate closure. This weakens our study slightly because several authors have supported the contention that the biology of open fractures in a patient with open physes differs from that in adults [9]. As there is no clear answer to whether or not closed treatment will yield similar results to operative treatment for different types of open tibia fractures in a pediatric population, a randomized trial may be appropriate.

With the exception of type II fractures, the philosophy of treatment of open fractures of the tibia has not significantly changed during the past three decades. Closed treatment or internal fixation are both viable options for type II fractures based on their relatively low incidence of infection. Type III fractures are more severe injuries that require more thought on a case-by-case basis. Our study also demonstrates a strong relationship between Gustillo sub-types and odds of infection in this population. Not surprisingly, union rates are also delayed with increasing injury severity.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest statement

There were no grants or external sources of funding utilized for this study. This study is a systematic review of available literature and does not require IRB review.

References

- 1.Bartlett CS, 3rd, Weiner LS, Yang EC. Treatment of type II and type III open tibia fractures in children. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(5):357–362. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199707000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buckley SL, Smith G, Thompson JD, Griffin PP. Open fractures of the tibia in children. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1990;72:1462–1469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckley SL, Smith GR, Sponseller PD, Thompson JD, Robertson WW, Jr, Griffin PP. Severe (type III) open fractures of the tibia in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16(5):627–634. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199609000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cullen MC, Roy DR, Crawford AH, Assenmacher J, Levy MS, Wen D. Open fracture of the tibia in children. J Bone Jt Surg Ser A. 1996;78(7):1039–1047. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujita M, Yokoyama K, Tsukamoto T, Aoki S, Noumi T, Fukushima N, Itoman M. Type III open tibial fractures in children. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2001;11(3):169–175. doi: 10.1007/BF02747661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimard G, Naudie D, Laberge LC, Hamdy RC. Open fractures of the tibia in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;332:62–70. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hope PG, Cole WG. Open fractures of the tibia in children. J Bone Jt Surg Ser B. 1992;74(4):546–553. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B4.1624514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwin A, Gibson P, Ashcroft P. Open fractures of the tibia in children. Injury. 1995;26(1):21–24. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(95)90547-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones BG, Duncan RDD. Open tibial fractures in children under 13 years of age—10 years experience. Injury. 2003;34(10):776–780. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreder HJ, Armstrong P. A review of open tibia fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:482–488. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199507000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy AS, Wetzler M, Lewars M, Bromberg J, Spoo J, Whitelaw GP. The orthopedic and social outcome of open tibia fractures in children. Orthopedics. 1997;20(7):593–598. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19970701-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson P, Karol LA, Rab GT. Open fractures of the tibia and femur in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16(5):621–626. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199609000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song KM, Sangeorzan B, Benirschke S, Browne R. Open fractures of the tibia in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16(5):635–639. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199609000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasko AW, Wilber JH. Open tibial fractures in children. Orthop Trans. 1989;13:547–548. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alonge TO, Ogunlade SO, Salawu SA, Adebisi AT. Management of open tibia fracture–Anderson and Hutchins technique re-visited. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2003;32(2):131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buehler KC, Green J, Woll TS, Duwelius PJ. A technique for intramedullary nailing of proximal third tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(3):218–223. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199704000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castillo RC, Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Patterson BM, LEAP Study Group Impact of smoking on fracture healing and risk of complications in limb-threatening open tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(3):151–157. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole PA, Zlowodzki M, Kregor PJ. Treatment of proximal tibia fractures using the less invasive stabilization system: surgical experience and early clinical results in 77 fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(8):528–535. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collinge C, Kuper M, Larson K, Protzman R. Minimally invasive plating of high-energy metaphyseal distal tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(6):355–361. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3180ca83c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunbar RP, Nork SE, Barei DP, Mills WJ. Provisional plating of Type III open tibia fractures prior to intramedullary nailing. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(6):412–414. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000153446.34484.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finkemeier CG, Schmidt AH, Kyle RF, Templeman DC, Varecka TF. A prospective, randomized study of intramedullary nails inserted with and without reaming for the treatment of open and closed fractures of the tibial shaft. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14(3):187–193. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gicquel P, Giacomelli MC, Basic B, Karger C, Clavert JM. Problems of operative and non-operative treatment and healing in tibial fractures. Injury. 2005;36(Suppl 1):A44–A50. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregory P, DiCicco J, Karpik K, DiPasquale T, Herscovici D, Sanders R. Ipsilateral fractures of the femur and tibia: treatment with retrograde femoral nailing and unreamed tibial nailing. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10(5):309–316. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199607000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris IA, Kadir A, Donald G. Continuous compartment pressure monitoring for tibia fractures: does it influence outcome? J Trauma. 2006;60(6):1330–1335. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196001.03681.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harvey EJ, Agel J, Selznick HS, Chapman JR, Henley MB. Deleterious effect of smoking on healing of open tibia-shaft fractures. Am J Orthop. 2002;31(9):518–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kai H, Yokoyama K, Shindo M, Itoman M. Problems of various fixation methods for open tibia fractures: experience in a Japanese level I trauma center. Am J Orthop. 1998;27(9):631–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kakar S, Firoozabadi R, McKean J, Tornetta P., 3rd Diastolic blood pressure in patients with tibia fractures under anaesthesia: implications for the diagnosis of compartment syndrome. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(2):99–103. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318032c4f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kakar S, Tornetta P., 3rd Open fractures of the tibia treated by immediate intramedullary tibial nail insertion without reaming: a prospective study. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(3):153–157. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3180336923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kakar S, Tornetta P., 3rd Segmental tibia fractures: a prospective evaluation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;460:196–201. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318050a3f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khatod M, Botte MJ, Hoyt DB, Meyer RS, Smith JM, Akeson WH. Outcomes in open tibia fractures: relationship between delay in treatment and infection. J Trauma. 2003;55(5):949–954. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000092685.80435.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manninen MJ, Lindahl J, Kankare J, Hirvensalo E. Lateral approach for fixation of the fractures of the distal tibia. Outcome of 20 patients. Technical note. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127(5):349–353. doi: 10.1007/s00402-006-0278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Brien T, Weisman DS, Ronchetti P, Piller CP, Maloney M. Flexible titanium nailing for the treatment of the unstable pediatric tibial fracture. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24(6):601–609. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200411000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ostrum RF. Treatment of floating knee injuries through a single percutaneous approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;375:43–50. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parekh AA, Smith WR, Silva S, Agudelo JF, Williams AE, Hak D, Morgan SJ. Treatment of distal femur and proximal tibia fractures with external fixation followed by planned conversion to internal fixation. J Trauma. 2008;64(3):736–739. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31804d492b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qidwai SA. Intramedullary Kirschner wiring for tibia fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(3):294–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sen C, Kocaoglu M, Eralp L, Gulsen M, Cinar M. Bifocal compression-distraction in the acute treatment of grade III open tibia fractures with bone and soft-tissue loss: a report of 24 cases. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(3):150–157. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200403000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Setter KJ, Palomino KE. Pediatric tibia fractures: current concepts. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(1):30–35. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000192520.48411.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tornetta P, 3rd, Collins E. Semiextended position of intramedullary nailing of the proximal tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;328:185–189. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199607000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tornetta P, 3rd, Weiner L, Bergman M, Watnik N, Steuer J, Kelley M, Yang E. Pilon fractures: treatment with combined internal and external fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7(6):489–496. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199312000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vranckx JJ, Misselyn D, Fabre G, Verhelle N, Heymans O, Van den hof B. The gracilis free muscle flap is more than just a “graceful” flap for lower-leg reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2004;20(2):143–148. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-820770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yue JJ, Churchill RS, Cooperman DR, Yasko AW, Wilber JH, Thompson GH. The floating knee in the pediatric patient. Nonoperative versus operative stabilization. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;376:124–136. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200007000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziran BH, Darowish M, Klatt BA, Agudelo JF, Smith WR. Intramedullary nailing in open tibia fractures: a comparison of two techniques. Int Orthop. 2004;28(4):235–238. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0567-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jainandunsing JS, van der Elst M, van der Werken CC (2005) Bioresorbable fixation devices for musculoskeletal injuries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD004324 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Manzur AY, Kuntzer T, Pike M, Swan A (2008) Glucocorticoid corticosteroids for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD003725 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Morton L, Bridgman S, Dwyer J, Theis J (2002) Interventions for treating femoral shaft fractures in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD003473. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Rome K, Handoll HHG, Ashford R (2005) Interventions for preventing and treating stress fractures and stress reactions of bone of the lower limbs in young adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD000450. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000450.pub22005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Rome K, Ashford RL, Evans A (2007). Non-surgical interventions for paediatric pes planus. ochrane Database Syst Rev 1: CD006311 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Willett KM, Pandit H, Upadhyay A (2008) Internal versus external fixation for treating distal tibial pilon fractures in adults (protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD006948. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006948

- 49.Annan IH, Moran M. (I) Indications for internal fixation of fractures in children. Curr Orthop. 2006;20(4):241–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cuor.2006.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arslan H, Kapukaya A, Kesemenli C, Subasi M, Kayikci C. Floating knee in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(4):458–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coles CP, Gross M. Closed tibial shaft fractures: management and treatment complications. A review of the prospective literature. Can J Surg. 2000;43(4):256–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Sanctis N, Della Corte S, Pempinello C. Distal tibial and fibular epiphyseal fractures in children: prognostic criteria and long-term results in 158 patients. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2000;9(1):40–44. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200001000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iobst CA, Tidwell MA, King WF. Nonoperative management of pediatric type I open fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(4):513–517. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000158779.45226.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Janarv P-M, Westblad P, Johansson C, Hirsch G. Long-term follow-up of anterior tibial spine fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15(1):63–68. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199501000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karrholm J. The triplane fracture: four years of follow-up of 21 cases and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1997;6(2 Part B):91–102. doi: 10.1097/01202412-199704000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kubiak EN, Egol KA, Scher D, Wasserman B, Feldman D, Koval KJ. Operative treatment of tibial fractures in children: are elastic stable intramedullary nails an improvement over external fixation? J Bone Jt Surg Ser A. 2005;87(8):1761–1768. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.01616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liow RYL, Montgomery RJ. Treatment of established and anticipated nonunion of the tibia in childhood. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(6):754–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moran M, Macnicol MF., II Paediatric epiphyseal fractures around the knee. Curr Orthop. 2006;20(4):256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.cuor.2006.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Myers SH, Spiegel D, Flynn JM. External fixation of high-energy tibia fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(5):537–539. doi: 10.1097/01.bpb.0000279033.04892.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nenopoulos SP, Papavasiliou VA, Papavasiliou AV. Outcome of physeal and epiphyseal injuries of the distal tibia with intra-articular involvement. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(4):518–522. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000158782.29979.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patari SK, Lee FY-I, Behrens FF. Coronal split fracture of the proximal tibia epiphysis through a partially closed physis: a new fracture pattern. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(4):451–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Skoll PJ, Hudson DA. Combined pedicled flaps for grade IIIB tibial fractures in children: a report of two patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;44(4):422–425. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200044040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor AH, Gargan MF. Plate and screw fixation in paediatric fractures. CME Orthop. 2003;3(3):77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vallamshetla VRP, De Silva U, Bache CE, Gibbons PJ. Flexible intramedullary nails for unstable fractures of the tibia in children. J Bone Jt Surg Ser B. 2006;88(4):536–540. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B4.17363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vanderhave KL, Miller D. Foot and ankle problems in the adolescent athlete. Curr Opin Orthop. 2005;16(2):45–49. doi: 10.1097/01.bco.0000157074.54110.43. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blaiser RD, Barnes CL. Open tibia fractures in children. Orthop Trans. 1992;16:83. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cramer KE, Limbird TJ, Green NE. Open fractures of the diaphysis of the lower extremity in children. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1992;74:218–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bax L, Yu LM, Ikeda N, Tsurata H, Moons KGM MIX (2008) Comprehensive free software for meta-analysis of causal research data: version 1.7. Available at: http://mix-for-meta-analysis.info [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Bax L, Yu LM, Ikeda N, Tsurata H, Moons KGM (2006) Development and validation of MIX: comprehensive free software for meta-analysis of causal research data. BMC Med Res Methodol 6:50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Gustilo RB, Anderson JT. Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones: retrospective and prospective analyses. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1976;58(4):453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gustilo RB, Mendoza RM, Williams DN. Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: a new classification of type III open fractures. J Trauma. 1984;24(8):742–746. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198408000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]