Abstract

Extracellular nucleotides can act as important intercellular signals in diverse biological processes, including the enhanced production of factors that are key to immune response regulation. One receptor that binds extracellular adenosine triphosphate released at sites of infection and injury is P2X7, which is an ionotrophic receptor that can also lead to the formation of a non-specific pore, activate multiple mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and stimulate the production of immune mediators including interleukin family members and reactive oxygen species (ROS). In the present report, we have investigated the signaling mechanisms by which P2X7 promotes monocytic cell mediator production and induces transcription factor expression/phosphorylation, as well as how receptor-associated pore activity is regulated by intracellular trafficking. We report that P2X7 stimulates ROS production in macrophages through the MAPKs ERK1/2 and the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase complex, activates several transcription factors including cyclic-AMP response element-binding protein and components of the activating protein-1 complex, and contains specific sequences within its intracellular C-terminus that appear critical for its activity. Altogether, these data further implicate P2X7 activation and signaling as a fundamental modulator of macrophage immune responses.

Keywords: P2X7, ROS, CREB, AP-1, Arg-based ER retention signals, Mediator production

Introduction

Extracellular nucleotides such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP), uridine triphosphate (UTP), and their metabolites (e.g., uridine diphosphate (UDP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP)) are now recognized as highly important signaling molecules that can mediate an array of physiological processes, including neurotransmission, muscle contraction, pain sensation, and diverse immune responses [1–4]. Adenine nucleotides are stored in high concentrations within vesicles of platelets and immune cells, such as basophils and mast cells, and can be released into the extracellular space upon degranulation or following cell lysis resulting from infection, inflammation, or tissue damage [5, 6]. These extracellular nucleotides initiate multiple downstream events through their binding to a family of cell surface receptors, including the P2 nucleotide receptors, which have been divided into two major subfamilies: G-protein-coupled P2Y receptors that can bind ATP, ADP, UTP, and UDP (depending of the receptor subtype) and the ionotropic P2X receptors that largely bind ATP [7–9].

The stimulation of P2X receptors, in particular P2X7, has been implicated as a key process in a variety of inflammatory conditions, including sepsis, arthritis, extrapulmonary tuberculosis, granuloma formation, and Alzheimer’s disease [10–16]. P2X7 is unique among the other P2X receptors in that it requires high concentrations (millimolar) of ATP, such as those observed at sites of inflammation, to be activated. In addition, P2X7 is sensitive to the synthetic ATP analog 3′-O-(4-benzoyl) benzoyl ATP (BzATP), and thus BzATP is often used to study P2X7 action. Upon ligand binding, P2X7 is linked to the formation of a cation channel that mediates the influx of Ca2+ and Na+ and the efflux of K+. Upon prolonged stimulation, P2X7 can also allow for the formation of a non-specific pore that permits the passage of molecules of up to 900 Da.

Among the many critical functions of P2X7 is its capacity to control various immune responses, e.g., P2X7 activation leads to the enhanced release of multiple immune modulators, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), it mediates host defense against intracellular pathogens, it initiates membrane blebbing, and it promotes apoptosis [8]. Interestingly, P2X7 ligation by extracellular ATP can also modulate lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated macrophage activation, and P2X7 stimulation is known to potentiate the release of several LPS-induced pro-inflammatory mediators, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α, and nitric oxide [17–22]. However, although there is a growing literature regarding several cell signaling and cytokine processing events that are initiated upon P2X7 activation, relatively little is known about the regulation of receptor trafficking and the mechanisms by which P2X7 activation can impact on long-term cellular processes such as the regulation of gene transcription. In this regard, we have reported that P2X7 action can influence LPS-stimulated expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and others have shown that P2X7 activation is not always linked to apoptosis [23–26], which is an event often associated with cell exposure to P2X7 agonists. These observations led to the hypothesis that, under certain circumstances, P2X7 stimulation may not only elicit immediate cellular responses, such as the potentiation of cytokine processing, but that it can also have an important effect on longer term cellular behavior via effects on gene expression.

Given that animal and human genetic studies support the concept that P2X7 is a major immune modulator and may be an effective therapeutic target [11–14, 27–29], in this report, we will discuss several key events associated with P2X7 signaling and trafficking, with an emphasis on their role in mediating/regulating the immune responses of monocytic cells. Specifically, we will provide evidence that P2X7 stimulation in macrophages promotes ROS production via the extracellular-regulated kinases-1 and 2 (ERK1/2) and the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase complex, and that ligand binding to P2X7 results in activation of the transcription factor cyclic-AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and the expression of key components of the transcription factor activating protein-1 (AP-1) complex. Because receptor trafficking appears critical for controlling cell responsiveness to extracellular ATP [7–9, 18, 30], we will also discuss the mechanisms by which P2X7 activity/trafficking may be regulated by specific residues in its C-terminus. As an overview, we will first discuss the general properties of P2X7 as well as human genetic and animal studies that have revealed several of the biological roles of this receptor.

General properties of P2X7

As noted above, extracellular nucleotides can bind to P2 receptors to elicit diverse cellular responses. There are two P2 receptor subfamilies, the seven-transmembrane spanning P2Y G-protein-coupled receptors and the double membrane spanning P2X cation channels. There are at least eight P2Y family members (P2Y1–2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11–14) and seven P2X receptors (P2X1–7) [8, 9]. All of the P2X receptors contain a short (<35 amino acids) intracellular N-terminal region, a large extracellular nucleotide-binding domain, and an intracellular C-terminus. The human nucleotide receptor P2X7 is composed of 595 amino acids and is unique in that it contains a C-terminus that is ∼120 amino acids longer than the next largest P2X receptor [8]. Deletions within the extended P2X7 C-terminal region that are N-terminal to residue 582 have been shown to reduce its pore-forming ability and to inhibit its expression on the cell surface [30]. Furthermore, the P2X7 C-terminus contains several potential protein–protein and protein–lipid interaction motifs, including an LPS/lipid-binding domain, PxxP sequences (which are known to bind to SH3 domains) [31], and an apparent trafficking domain (Fig. 1; also see “P2X7 contains a trafficking domain in its C-terminus” section below).

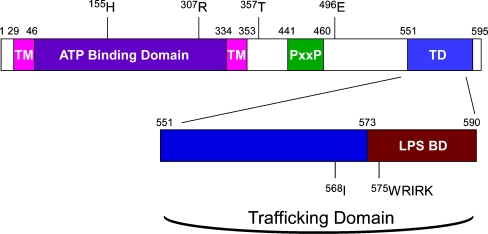

Fig. 1.

General diagram of P2X7 highlighting its two transmembrane domains (TM), the extracellular ATP-binding domain, the potential SH3 domain-interacting region (PxxP), the trafficking domain (TD), and the LPS-binding domain (LPS BD). Several of the identified polymorphic amino acids along with a sequence within the putative trafficking domain of the receptor are also indicated

P2X7 in animal models of disease

Many in vivo animal studies have revealed the importance of P2X7 in various diseases. Studies in rodents have directly implicated P2X7 in immune response regulation especially in the context of exacerbating arthritic symptoms and inhibiting Chlamydia infection. For example, mice deficient in P2X7 exhibit decreased monoclonal anti-collagen-induced arthritis in comparison to wild-type counterparts, and rats treated with oxidized ATP experience less adjuvant-induced pain than control animals [11, 12]. In support of the hypothesis that P2X7 plays a role in host defense against pathogens, P2X7-deficient mice were reported to exhibit increased vaginal Chlamydia infection in comparison to wild-type mice [27]. These in vivo results illustrate the involvement of P2X7 in exacerbating arthritic pain and attenuating pathogen infection, supporting the idea that targeting P2X7 may be useful in treating certain inflammatory diseases.

P2X7 polymorphisms and altered expression levels in human disease

In addition to the aforementioned animal studies, there is growing evidence that P2X7 plays an important role in human disease. In this regard, several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified in the promoter, introns, and coding sequences of P2X7 [29, 32–41]. Investigations evaluating the significance of P2X7 polymorphisms and overall protein expression levels support the idea that cells need to correctly respond to extracellular ATP via P2X7 for the mediation of several functions, including neurotransmission, mycobacterial killing, and appropriate cell death. Genetic analyses have linked P2X7 polymorphisms to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) infection and bipolar affective disorder [13, 14, 28, 29]. The P2X7 A1513C polymorphism, which results in mutation of Glu496 to Ala, has been associated with TB in two different population groups [13, 14], and one report has shown that a SNP located in the promoter at position −762 is protective against the bacterium [28]. These results indicate that analysis of P2X7 may eventually be used to assess an individual’s susceptibility to TB infection.

Because P2X7 activation is often associated with apoptosis, it is noteworthy that several groups have proposed that P2X7 may be used as a cancer biomarker [42–45]. In support of this concept, a few studies have shown that P2X7 messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein levels are altered in cancer cells in comparison to normal tissue [43–47], and P2X7 SNPs have been found in colorectal cancers [42]. Gorodeski and colleagues have observed that P2X7 is expressed at lower levels in uterine cancer and cervix squamous carcinoma in comparison to normal tissue and that uterine cervical cells express a 258 amino acid-truncated P2X7 variant that antagonizes the ability of the full-length receptor to promote apoptosis [45, 47, 48]. In contrast, thyroid papillary carcinoma cells express higher levels of P2X7 in comparison to normal thyroid tissue, and it has been suggested that this increased level of P2X7 and subsequent increase in intracellular Ca2+ results in the enhanced release of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) [44]. Altogether, these findings associating P2X7 expression and SNPs to human disease reveals that P2X7 is a highly complex protein that plays an essential role in responding to extracellular ATP.

P2X7 modulation of innate immunity

Stimulation of P2X7 is known to result in the activation of several cellular events including K+/Ca2+-mediated signaling and the activation of phospholipase D and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades. In addition, many investigations have focused on the role of P2X7 in the modulation of cellular responses to classical activators such as LPS, e.g., P2X7 signaling in the classically activated macrophage has been shown to potentiate such diverse processes as the release of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-18, the expression of iNOS, and the activation of metalloproteases and caspases (see [49–51] for reviews of P2X7 signaling in immune cells).

Recent studies have revealed additional roles for P2X7 signaling in mediator production and transcriptional regulation of unprimed immune cells. For example, reports by our lab and others have shown that P2X7 activation results in ROS production, which may act as a second messenger in several P2X7 agonist-induced events [16, 17, 21, 52, 53]. However, the mechanisms by which P2X7 promotes ROS production are less well understood, and ROS generation in response to P2X7 agonists has not been demonstrated in primary cells. However, in this report, we show that P2X7 mediates ROS production in primary human monocytes and that generation of ROS in RAW 264.7 likely involves ERK1/2 and the NADPH oxidase complex. In addition, although prolonged P2X7 activation can result in apoptotic or necrotic cell death [8, 54], it has been found that transient stimulation of P2X7 does not lead to apoptosis [24–26] but can induce cell proliferation [25, 26]. These reports, together with the findings that P2X7 regulates the expression of iNOS and early growth response factor-1 (EGR-1) expression support the idea that P2X7 can function in the control of gene transcription [17, 55]. To this end, we also tested the hypothesis that P2X7 stimulation results in the activation of several transcription factors in macrophages including CREB and AP-1 (see “P2X7-mediated transcription factor activation” section below).

P2X7 activation mediates NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS production

The production of ROS, such as superoxide (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (·OH), is vital to a variety of biological processes. When properly regulated, ROS maintain an integral role in host defense, regulation of apoptosis, and modulation of cell signaling. The generation of ROS has also been implicated in several human disorders, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, ischemia/reperfusion injury, neurodegenerative disease, chronic granulomatous disease, and the deleterious effects of aging [18, 56]. The use of ROS by leukocytes in the defense against pathogens is well recognized, but the role of ROS as second messengers is sill emerging, e.g., ROS generation has been linked to the activation of transcription factors, including apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1)/Ref1, nuclear factor κB (NFκB), and AP-1, as well as the signaling kinases p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (p90RSK) and various MAPKs [21, 57–65]. Although the mechanisms of ROS-induced signaling have not been fully resolved, multiple processes including inactivation of phosphatases through cysteine modification and the activation of redox sensitive systems, have been proposed [57, 61, 62, 66].

With respect to P2X7 and ROS generation, Ferrari et al. have noted that activation of NFκB in microglial cells by P2X7 agonists is sensitive to antioxidants, indicating that ROS may play a role in this endpoint [67]. Similarly, we have observed that stimulation of the MAP kinases ERK1/2, p38, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in the murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 by P2X7 agonists is sensitive to antioxidants, suggesting that ROS may play a more global role in P2X7 signaling [21]. Although P2 receptor potentiation of ROS production has been seen with several immune cell types, the role of P2X7 in nucleotide-dependent ROS production in macrophages is less well known. To this end, we have shown that P2X7 agonists stimulate ROS production in RAW macrophages but not in a RAW cell line containing a non-functional P2X7 receptor [21]. However, because the behavior of cell lines may differ from primary cells, we have now tested whether P2X7 agonists can promote ROS production in human primary cells. As shown in Fig. 2a, we have observed that the P2X7 agonist BzATP can stimulate ROS production in primary human monocytic cells to levels even greater than that observed with murine RAW 264.7 macrophages. These results reveal that this effect of P2X7 agonists is not restricted to cell lines and is characteristic of primary cells as well.

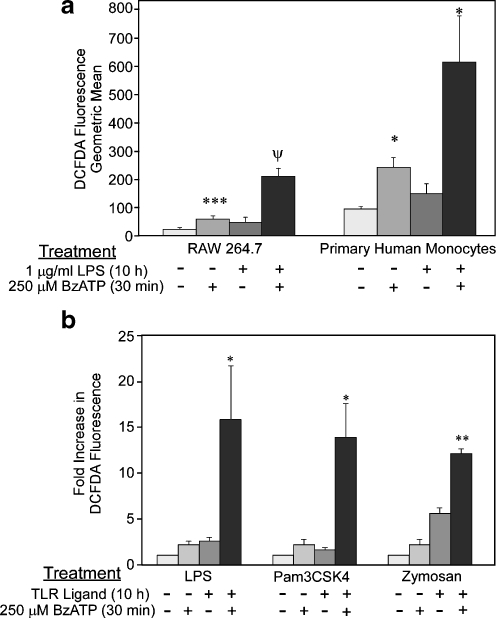

Fig. 2.

The P2X7 agonist BzATP stimulates ROS production in primary human monocytic cells. a RAW 264.7 cells (n = 12) were cultured as described [21] and primary human monocytes (n = 5) were purified and cultured as outlined earlier [105]. The cells were first treated with HEPES buffer (control) or 1 μg/ml LPS (E. coli, serotype 0111:B4) for 10 h, and then transferred to flow cytometry tubes (5 × 105 cells/tube) and loaded with 10 μM 2′,7′-dichloro-dihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were then treated with either HEPES buffer (control) or 250 μM BzATP for 30 min. DCFDA fluorescence was assessed using flow cytometry as detailed previously [21]. The data are plotted as geometric mean (±SEM) of DCFDA fluorescence. b RAW 264.7 cells were first treated with HEPES buffer (control), 1 μg/ml LPS, 1 μg/ml PamCSK4, or 250 μg/ml zymosan for 10 h, and then transferred to flow cytometry tubes (5 × 105 cells/tube) and loaded with 10 μM DCFDA for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were then treated with either HEPES (control) or 250 μM BzATP for 30 min. DCFDA fluorescence was assessed using flow cytometry. The data are plotted as the mean (±SEM) fold increase over control (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, and ψp < 0.0001 as compared to control pretreated, control-induced DCFDA fluorescence

Past studies have shown that P2X7 agonists are able to modulate macrophage activation in response to LPS, resulting in increased pro-inflammatory mediator production [17, 18, 23, 56, 67–76]. Because LPS is known to activate ROS production in leukocytes [77, 78], and because P2X7 activation is able to augment several LPS-induced signaling events, we tested the hypothesis that P2X7-stimulated ROS production is enhanced in LPS-primed macrophages. We observed that LPS-primed macrophages stimulated with P2X7 agonists display synergistic ROS production greater than either stimulus alone [21]. However, it is unclear if P2X7 activation can synergize with other Toll-like receptor (TLR) systems besides TLR4 (which is an LPS receptor). Thus, we have now tested the capacity of P2X7 ligands to cooperate with other TLR ligands in the generation of ROS, and as shown in Fig. 2b, we detect synergistic ROS production after P2X7 agonist treatment of macrophages primed with other TLR ligands, namely the lipopeptide Pam3CSK4 (a TLR2/1 ligand) and zymosan (a TLR2/6 ligand). These data further implicate P2X7 activation and signaling as a fundamental modulator of macrophage immune responses in response to multiple TLR ligands.

Although ROS can be generated by various enzyme systems, including NADPH oxidase, nitric oxide synthases, xanthine oxidase, and the mitochondrial respiratory chain, we first tested the hypothesis that the major system controlling O2− production by P2X7 agonists in macrophages is NADPH oxidase. The NADPH oxidase complex is comprised of several differentially regulated subunits that accept an electron from NADPH and donate it to molecular oxygen (see [78, 79] for comprehensive reviews). A link between NADPH oxidase activation and P2X7 signaling in monocytic cells appears plausible in that Parvathenani et al. demonstrated that P2X7 agonists can modulate the localization of the NADPH oxidase subunit p67phox in microglia [16], and Noguchi et al. found that P2X7 agonist-induced ROS production is sensitive to the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin and can be attenuated in RAW 264.7 macrophages by reducing the expression of the NADPH subunit gp91phox [52]. Similarly, we have found that P2X7 agonist-induced JNK phosphorylation in RAW macrophages is sensitive to the NADPH oxidase inhibitor diphenyliodonium and that ROS production stimulated by P2X7 agonists in LPS-primed RAW 264.7 cells is sensitive to the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin (data not shown).

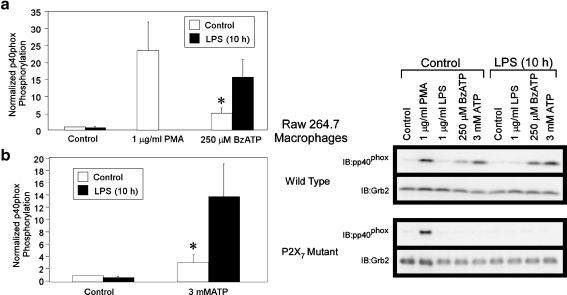

Many stimuli, including LPS, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), and zymosan, increase the expression of NADPH oxidase subunits in leukocytes and can induce their spatiotemporal assembly and activation [77, 78, 80]. To further characterize P2X7 modulation of the NADPH oxidase complex in macrophages, we assessed the effect of P2X7 agonists on the phosphorylation of a cytosolic subunit of NADPH oxidase, p40phox. As shown in Fig. 3, treatment of RAW macrophages with BzATP or high doses of ATP results in p40phox phosphorylation, and this process is enhanced after LPS priming. These stimuli had no detectable effect on total p40phox levels (data not shown). To test the receptor specificity, we evaluated p40phox phosphorylation in response to the administration of P2X7 agonists to a RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line expressing a non-functional P2X7 mutant. We found that although treatment with PMA was able to induce p40phox phosphorylation in the P2X7 mutant cell line, P2X7 activity was critical for BzATP/ATP-induced phosphorylation of p40phox (Fig. 3). Further support for P2X7 involvement in p40phox phosphorylation comes from the observation that agonists (UTP, UDP, ADP, and low ATP doses) selective for other nucleotide receptors did not stimulate p40phox phosphorylation (data not shown), illustrating that the pharmacological profile of p40phox phosphorylation is consistent with P2X7 stimulation. Together, these data reveal that P2X7 stimulates ROS production in a manner that is concomitant with the phosphorylation of NADPH oxidase subunits.

Fig. 3.

P2X7 agonists promote p40phox phosphorylation in murine macrophages. RAW 264.7 cells expressing either wild-type or defective P2X7 were pretreated with either HEPES buffer (control) or 1 μg/ml LPS for 10 h. The cells were then treated with either HEPES (control), 1 μg/ml LPS, 250 μM BzATP, or 3 mM ATP for 30 min or 1 μg/ml PMA for 10 min. Left panel: a phosphorylation of p40phox in murine macrophages expressing wild-type P2X7 and treated with either 1 μg/ml PMA (as a positive control) or 250 μM BzATP. The results of nine independent experiments were combined and are presented as the mean (±SEM). b Phosphorylation of p40phox in murine macrophages expressing wild-type P2X7 and treated with 3 mM ATP. The results were obtained from six independent experiments and plotted as the mean (±SEM). *p < 0.05 as compared to control pretreated, control-induced p40phox phosphorylation. Right panel: a representative immunoblot displaying p40phox phosphorylation in response to the indicated stimuli is shown for RAW 264.7 cells expressing either wild-type (upper blot) or defective P2X7 (lower blot). Immunoblotting was performed with anti-Grb2 antibody as a loading control

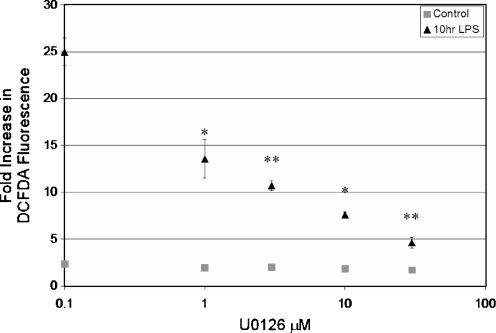

Many protein kinases have been implicated in the stimulus-induced assembly and activation of the NADPH oxidase complex, including protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms, MAPKs, and p21-activated kinase [78, 79, 81–83]. Given that P2X7 activation results in the phosphorylation of NADPH oxidase subunits and subsequent ROS production, we examined the involvement of the MEK–ERK1/2 MAPK network in P2X7-stimulated ROS production. To this end, RAW macrophages were pretreated with increasing concentrations of U0126, a MEK1/2 inhibitor, followed by stimulation with BzATP, and then ROS production was assessed by flow cytometry. We found that U0126 pretreatment is able to decrease P2X7 agonist-stimulated ROS production and greatly attenuate the enhanced ROS production found in P2X7 agonist-stimulated LPS-primed macrophages (Fig. 4). Conversely, general antagonists of several PKC isoforms (such as Go6976 and rottlerin), as well as p38 MAPK (i.e., SB203580), had little effect (0–3%) on P2X7 agonist-stimulated ROS levels in LPS-primed macrophages. These data support the concept that the MEK/ERK pathway is critical for P2X7-induced ROS production (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The MEK/ERK cascade appears critical for P2X7-induced ROS production. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with either HEPES buffer (control) or 1 μg/ml LPS for 10 h, and then transferred to flow cytometry tubes (5 × 105 cells/tube) and loaded with 10 μM DCFDA for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were then pretreated with DMSO or increasing concentrations of UO126 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA; 130 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then treated with either HEPES (control) or 250 μM BzATP for 30 min. Flow cytometry was performed by measuring 10,000 cells and excluding propidium iodide-stained (dead) cells from the analysis. The data are plotted as the mean (±SEM) fold increase over control (n = 3). *p < 0.01, **p < 0.005 as compared to LPS-pretreated, BzATP-induced DCFDA fluorescence

P2X7-mediated transcription factor activation

Activation of P2X7 has been linked not only to apoptosis, but also to lymphocyte cell proliferation [25, 84] and transcriptional activation in immune cells [85]. As noted above, several studies have implicated P2X7 activation in regulating the processing and release of interleukin family members and the promotion of iNOS expression. A recent mRNA microarray analysis comparing P2X7 agonist-treated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from tuberculosis patients with P2X7 agonist-treated cells from control patients revealed differential gene expression, suggesting a potentially complex role of P2X7 in gene regulation [86]. Thus, although P2X7 stimulation appears to affect gene expression, the mechanisms by which these events occur are not well-defined. In this regard, a few studies evaluating the mechanisms of P2X7-induced modulation of gene expression have suggested a role for several transcription factors including NFκB, nuclear factor of activated T cells, signal transducers and activators of transcription [85], and, as discussed below, CREB and AP-1.

The transcription factor CREB is a ubiquitously expressed protein that contributes to many cellular processes such as glucose homeostasis, growth factor-dependent cell survival, and inflammatory mediator production [87]. In general, CREB mediates the activation of cAMP-responsive genes by binding as a dimer to conserved CREB response elements (CREs) (5′-TGACGTCA-3′) in the promoter regions of target genes. The activation of CREB requires the phosphorylation of the protein at Ser-133 (S133), which promotes the recruitment of the transcriptional co-activator CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300, thereby enabling gene transcription [87, 88].

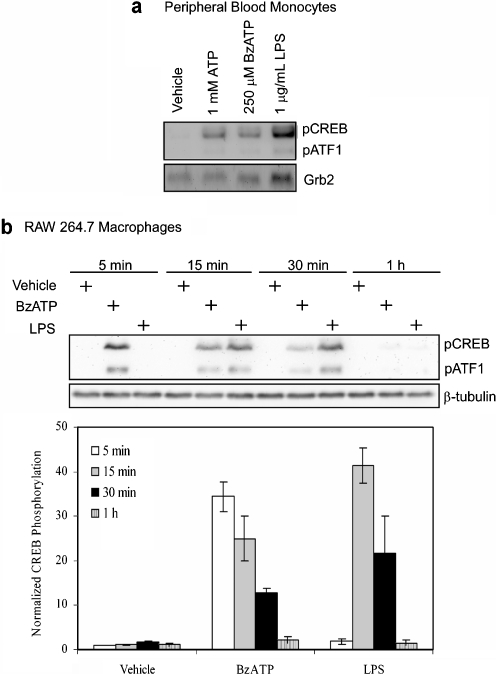

CREB regulation is recognized to play a role in leukocyte function [88], yet little is known concerning the effect of P2X7 stimulation on CREB activation, although Potucek et al. observed BzATP-induced CREB phosphorylation in murine microglial cells [89]. In the present report, we show that stimulation of primary human PBMCs and RAW 264.7 with P2X7 agonists (BzATP and high doses of ATP) induces the rapid and transient phosphorylation of CREB (at Ser-133) and the related factor activating transcription factor-1 (ATF-1; Fig. 5a, b). As shown in Fig. 5b, CREB phosphorylation in murine macrophages is detectable within 5 min of ligand addition, it occurs more rapidly than in response to LPS, and it is complete within 1 h. In addition, we have observed: (a) a lack of nucleotide-induced CREB phosphorylation in RAW 264.7 cells expressing a non-functional P2X7, (b) a gain of nucleotide-induced CREB phosphorylation in HEK293 cells that heterologously express human P2X7, and (c) the induction of CREB/CBP complex formation (which is necessary for CREB transcriptional activation) in macrophages treated with P2X7 agonists (data not shown, Gavala et al., in preparation). Altogether these data suggest that P2X7 stimulation modulates monocytic gene expression through the activation of CREB.

Fig. 5.

P2X7 agonists induce CREB Ser-133 phosphorylation in monocytic cells. a Isolated peripheral human blood monocytes (1 × 106 cells/well) were treated with either vehicle (HEPES buffer), 1 mM ATP, 250 μM BzATP, or 1 μg/ml LPS for 15 min. A representative immunoblot displaying CREB Ser-133 phosphorylation (pCREB) is shown (n = 4). The pCREB antibody recognizes both pCREB and phosphorylated ATF-1 (pATF1), thus it is also shown. Immunoblotting was performed with anti-Grb2 antibody as a loading control. b Murine RAW 264.7 macrophages (3 × 105 cells/well) were stimulated with either vehicle (HEPES), 250 μM BzATP or 1 μg/ml LPS for the indicated time. A representative immunoblot displaying pCREB/pATF1 is shown. Immunoblotting was performed with anti-β-tubulin antibody as a loading control. Results of the three independent experiments were combined and plotted as the mean (±SEM)

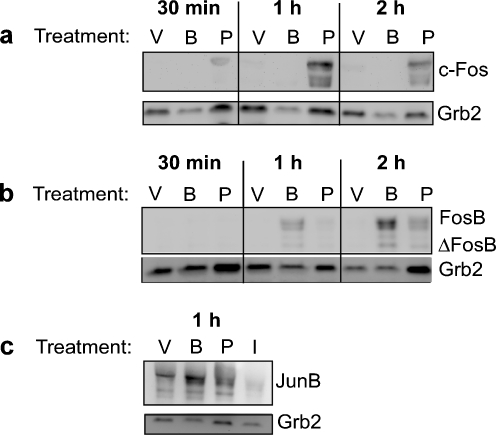

Activating protein-1 is a collective term for dimeric transcription factors composed of Jun, Fos, or ATF subunits that bind to a common 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate response elements (5′-TGAGTCA-3′) found in the promoter regions of many inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [90, 91]. Previous evidence for AP-1 activation by extracellular ATP comes from studies examining B lymphocytes. In these experiments, administration of extracellular ATP to human tonsilar B lymphocytes was found to increase cFos mRNA levels within 30 min [92]. Furthermore, co-treatment of human fetal astrocytes with IL-1β and ATP was seen to induce an activation of AP-1 that is more robust than that observed with IL-1β alone [93], and treatment with P2 receptor antagonists inhibits cytokine-induced AP-1 activation [93, 94]. It has been suggested that stimulation of Jurkat T cells induces AP-1 DNA-binding activity that results from increased c-Jun and cFos expression [84]. Conversely, in the present report, we show that stimulation of human PBMCs with P2X7 agonists does not appear to enhance cFos expression (Fig. 6a) but does substantially induce the expression of the FosB and JunB proteins (Fig. 6b, c). These results are the first report linking the activation of a nucleotide receptor to FosB and JunB induction. Interestingly, the effect of P2X7 activation on FosB levels is detectable within 1 h of treatment with BzATP alone and suggests that FosB may be a unique transcriptional regulator of P2X7-initiated signaling. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) in BzATP-treated RAW 264.7 cells reveal an increase in protein binding to an AP-1 consensus oligonucleotide compared to vehicle treatment, and this AP-1 complex is supershifted with antibodies directed toward FosB, JunB, and c-Jun (not shown, Gavala et al., in preparation). However, stimulation of P2X7 does not induce AP-1 activation in all phenotypic backgrounds. Stimulation of N9 and N13 microglial cells with 3 mM ATP inhibits the basal DNA-binding activity of AP-1, suggesting that P2X7-mediated AP-1 activation is cell type-specific (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

P2X7 agonists induce AP-1 protein expression in primary human monocytes. Isolated peripheral human blood monocytes were stimulated with either vehicle (HEPES), 250 μM BzATP, 1 μg/ml PMA, or 10 μM ionomycin (c) for 5 min. The media was replaced and the cells were incubated at 37°C for the indicated times (PMA treatment was reintroduced to the new media) and immunoblotted for a cFos, b FosB, or c JunB expression. Immunoblotting was performed with anti-Grb2 antibody as a loading control. The results are representative of three independent experiments

The activation of certain protein kinases by P2X7 agonists has been implicated in subsequent AP-1 activation in several immune cells. Stimulation of Jurkat T cells with P2X7 agonists induces the activation of the lymphoid-specific cytoplasmic protein tyrosine kinase p56lck [84]. Although the activation of cFos and c-Jun by P2X7 ligands occurs in Jurkat T cells, it is absent in a p56lck-deficient JCaM1T cell line [84], suggesting that this kinase may play a role in P2X7-induced AP-1 activation in T cells. A role for MAPKs in P2X7-dependent AP-1 activation in monocytic cells has also been supported. The transactivation of c-Jun is augmented by the phosphorylation of Ser-63 and -73 by JNK1/2. Studies from our lab and others have noted JNK1/2 activation following stimulation of monocytic cells with P2X7 agonists [21, 68, 95]. Furthermore, co-stimulation of RAW 264.7 cells with LPS and BzATP results in enhanced JNK activation compared to either stimulus alone [68]. Of note, P2X7 agonist-induced JNK activation in RAW 264.7 cells is attenuated by N-acetylcysteine and ascorbic acid, implicating a role for ROS in P2X7-dependent AP-1 activation [21]. In addition, we have observed that P2X7 agonist-induced FosB and JunB expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages is abrogated in a dose-dependent fashion by the MEK1/2 antagonist UO126, suggesting that the MEK/ERK cascade is upstream of the expression of these AP-1 proteins in macrophages (Gavala et al., in preparation).

Although reporter assays and EMSAs have often been used to demonstrate activation of transcription factors by P2X7 agonists, little is known about the target genes of these transcription factors. To this end, preliminary studies by our lab have suggested a novel role for CREB in P2X7-mediated FosB expression, i.e., transfection of dominant-negative CREB vectors into HEK293 cells heterologously expressing P2X7 abrogates P2X7 agonist-induced FosB expression (Gavala et al., in preparation).

P2X7 contains a trafficking domain in its C-terminus

The intracellular trafficking of plasma membrane receptors is a critical component of their regulation. P2X7 trafficking has not been widely explored, and it is unclear how newly synthesized P2X7 subunits are transported from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the surface and whether P2X7 internalization or trafficking to the plasma membrane is controlled by extracellular signals. It is also not clear whether P2X7 recycles following internalization or whether the receptor contains signals within its sequence that regulate its transport through the cell. Addressing these issues will increase our understanding of how P2X7 is globally regulated and how cells mediate their responsiveness to extracellular ATP.

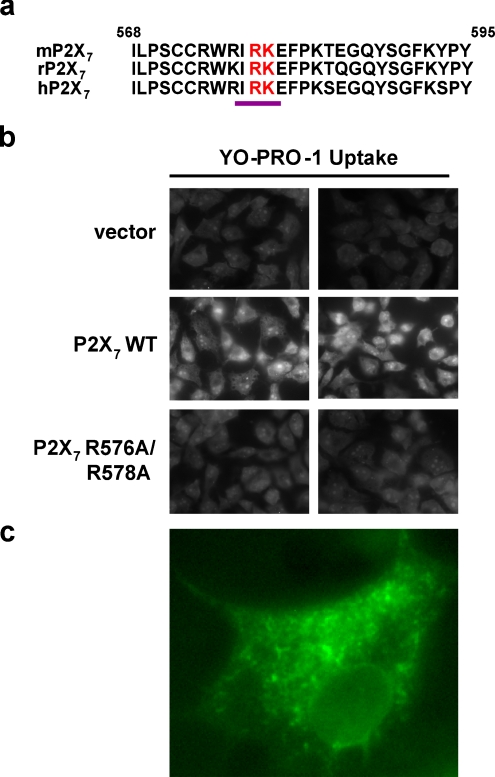

Our lab and those of Wiley, Petrou, and colleagues have provided evidence supporting the concept that P2X7 contains a trafficking domain in its distal C-terminal region that is critical for cell surface localization. Point mutations and deletions within this region reduce P2X7 surface expression and pore activity [30, 34, 96]. When P2X7 is truncated at residues 551–581, it exhibits significantly reduced activity and plasma membrane localization [30], and three polymorphisms, I568N, R574H, and R574L, have been identified in this area of the receptor [34, 42, 97]. T lymphocytes and natural killer cells from individuals who are heterozygous for the I568N polymorphism have reduced ATP-induced pore-forming ability, and exogenously expressed P2X7 with the I568N mutation is poorly expressed on the surface of HEK293 cells [34]. We have previously found that mutation of Arg578 and Lys579, which are localized in the LPS-binding motif (Fig. 1), drastically reduces the ability of P2X7 to localize on the plasma membrane and to promote BzATP-induced cell death [96]. Although the P2X7 R578E/K579E mutant does not appear to be stably expressed on the cell surface at 37°C, it does localize to the plasma membrane at 27°C, suggesting that the double mutant is internalized more readily than wild-type receptor. These findings lead us to speculate that P2X7 contains specific signals within its C-terminus that direct its intracellular trafficking.

One aspect of P2X7 trafficking that is less well characterized entails the mechanisms by which it is transported from the ER to the cell surface. Several studies have shown that newly synthesized subunits of integral membrane proteins, including N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), glutamate receptor, and γ-aminobutyric acid type B (GABAB) receptor, are retained in the ER before the properly assembled receptors and are further transported through the secretory pathway [98]. The NMDA and GABAB subunits possess arginine (Arg)-based ER retention/retrieval signals that prevent improperly assembled subunits from trafficking to the Golgi apparatus until assembly is complete and the signal is masked [99, 100]. These ER retention/retrieval sequences were first discovered in major histocompatibility complex class II proteins and have also been characterized in inward rectifier potassium channel and sulfonylurea receptor subunits [101, 102]. The Arg-based ER retention/retrieval consensus sequence is ϕ/ψ/R-R-X-R, where ϕ/ψ is an aromatic or bulky hydrophobic residue and X is any amino acid but is generally not a negatively charged or small, non-polar residue [98].

In view of the above discussion, we predict that P2X7 contains a RXR retention/retrieval signal at amino acid 576 that lies within the sequence WRIR, which conforms to the consensus sequence ϕ/ψ/R-R-X-R (Fig. 7a). To test the hypothesis that P2X7 contains an RXR ER retention/retrieval sequence at residue 576, a pore activity assay was conducted as an indirect readout for cell surface expression. In this experiment, COS7 cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant P2X7, stimulated with BzATP, and imaged for relative dye uptake as a measure of ligand-dependent pore formation. As shown in Fig. 7b, mutation of human R576 and R578 to Ala substantially reduces the activity of the receptor. Cells take up the dye YO-PRO-1 when wild-type P2X7 is expressed but exhibit drastically reduced dye uptake in the presence of the RXR mutant or the vector control. These findings, together with the information available about Arg-based signals in other receptors, provide initial support for the idea that P2X7 contains an RXR ER retention/retrieval sequence in its C-terminus in the area surrounding residue 576.

Fig. 7.

Mutation of two arginine residues in the P2X7 C-terminal region reduces receptor-mediated pore-forming activity. a The distal C-terminal sequences of mouse, rat, and human P2X7 were aligned. The proposed Arg-based ER retention signal is underlined, and Arg578 and Lys579 are highlighted in red. b COS7 cells were transfected with pcDNA3, P2X7/pcDNA3, or P2X7 R576A/R578A/pcDNA3. Sixteen to 24 h later, the cells were treated with 250 μM BzATP in the presence of 1 μM YO-PRO-1 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed, and imaged using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope. These data represent one of five independent experiments. P2X7 R576A/R578A/pcDNA3 was generated from P2X7/pcDNA3 (accession number BC011913) by site-directed mutagenesis. c COS7 cells were transfected with eYFP-P2X7/pCMV, fixed the next day with 4% paraformaldehyde, imaged using a Zeiss 200M Axiovert inverted microscope, and deconvolved. P2X7 was subcloned into the plasmid eYFP/pCMV, which was a generous gift from Dr. Melanie Cobb (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center)

Although our previous findings revealing that the P2X7 mutant R578E/K579E does not express on the cell surface seems counterintuitive to the idea that P2X7 possesses an ER retention/retrieval sequence, we speculate that cells prematurely traffic the R578E/K579E P2X7 mutant from the ER before it is properly assembled, and once it reaches the plasma membrane, it becomes quickly down-regulated because it is non-functional or lacks appropriate interaction with specific lipids. Alternatively, the P2X7 R578E/K579E mutation and not the mutation of an RXR signal prevents P2X7 from localizing to the cell surface. In this regard, Marshall and colleagues have shown that a RK/AA mutation in the C-terminus of the GluR5-2b kainate receptor subunit disrupts ER retention [103].

Another unresolved issue is whether the trafficking of P2X7 from intracellular compartments to the plasma membrane is stimulated by extracellular signals, as it is for the major insulin-responsive glucose transporter GLUT4, and has been reported for the NADPH oxidase complex [79, 80, 104]. We analyzed the localization of P2X7 fused to enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP) and found that it is predominantly localized in intracellular pools (Fig. 7c). We are now in a position to explore the critical hypothesis that the trafficking of P2X7 to and from these intracellular pools to the plasma membrane is stimulated by extracellular signals.

Summary

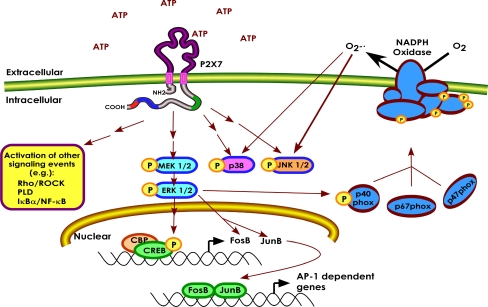

The ionotrophic receptor P2X7 is thought to be a major immune modulator that responds to extracelluar ATP at sites of inflammation and tissue damage. Although several human genetic and animal studies have demonstrated the importance of P2X7 in immune function, many questions remain concerning P2X7 signaling and the regulation of its activity via intracellular trafficking. We have investigated the mechanisms by which P2X7 promotes inflammatory mediator production and the poorly understood link between activation of P2X7 and gene transcription (Fig. 8). Specifically, we have reported here that P2X7 promotes ROS production in human monocytes and that production of this immune regulator is dependent upon the MEK/ERK cascade and likely involves the phosphorylation of the NADPH oxidase subunit p40phox. We have further demonstrated that P2X7 activates the transcription factors CREB and specific members of the AP-1 complex. Activation of P2X7 results in the phosphorylation of CREB at a serine residue that is critical for its activity, and it appears that activation of CREB in response to P2X7-initiated signaling is linked to FosB induction by P2X7 agonists. In addition, we provide support for the idea that P2X7 contains an Arg-based ER retention/retrieval sequence that is located within the P2X7 LPS-binding domain and is important for regulating its activity (Fig. 8). These findings undergird the concepts that P2X7 modulates mediator production and transcriptional activity as an immune response mechanism and that P2X7 activity is tightly controlled through trafficking regulation.

Fig. 8.

Proposed model of several of the key events by which P2X7 promotes the production of immune mediators and activates gene expression. Stimulation of P2X7 leads to enhanced ROS formation via the MAPKs ERK1/2 and the NADPH oxidase complex and stimulates gene transcription by activating CREB and increasing the expression of the AP-1 proteins FosB and JunB. In addition, specific residues in the putative trafficking domain of P2X7 are required for proper localization and full activation of the receptor

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Mary Ellen Bates and Greg Wiepz for critical comments about the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants 1 U19 AI070503, 2 R01 HL069116, and 1 P01 HL0885940 to PJB, a Hartwell Foundation postdoctoral fellowship to LYL, NIH Molecular & Cellular Pharmacology Training Grant T32 GM008688 to LMH, and NIH Hematology Training Grant T32 HL07899 to MLG.

References

- 1.Vassort G (2001) Adenosine 5′-triphosphate: a P2-purinergic agonist in the myocardium. Physiol Rev 81:767–806 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Sawynok J (1998) Adenosine receptor activation and nociception. Eur J Pharmacol 347:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bours MJ, Swennen EL, Di Virgilio F (2006) Adenosine 5′-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacol Ther 112:358–404 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Burnstock G (2007) Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol Rev 87:659–797 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Gordon JL (1986) Extracellular ATP: effects, sources and fate. Biochem J 233:309–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Dubyak GR (1991) Signal transduction by P2-purinergic receptors for extracellular ATP. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 4:295–300 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Boeynaems JM, Communi D, Gonzalez NS (2005) Overview of the P2 receptors. Semin Thromb Hemost 31:139–149 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.North RA (2002) Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev 82:1013–1067 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Burnstock G (2007) Purine and pyrimidine receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci 64:1471–1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Schneider EM, Vorlaender K, Ma X (2006) Role of ATP in trauma-associated cytokine release and apoptosis by P2X7 ion channel stimulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1090:245–252 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Dell’Antonio G, Quattrini A, Cin ED (2002) Relief of inflammatory pain in rats by local use of the selective P2X7 ATP receptor inhibitor, oxidized ATP. Arthritis Rheum 46:3378–3385 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Labasi JM, Petrushova N, Donovan C (2002) Absence of the P2X7 receptor alters leukocyte function and attenuates an inflammatory response. J Immunol 168:6436–6445 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Nino-Moreno P, Portales-Perez D, Hernandez-Castro B (2007) P2X7 and NRAMP1/SLC11 A1 gene polymorphisms in Mexican mestizo patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol 148:469–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Fernando SL, Saunders BM, Sluyter R (2007) A polymorphism in the P2X7 gene increases susceptibility to extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175:360–366 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Mizuno K, Okamoto H, Horio T (2001) Heightened ability of monocytes from sarcoidosis patients to form multi-nucleated giant cells in vitro by supernatants of concanavalin A-stimulated mononuclear cells. Clin Exp Immunol 126:151–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Parvathenani LK, Tertyshnikova S, Greco CR (2003) P2X7 mediates superoxide production in primary microglia and is up-regulated in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem 278:13309–13317 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Hu Y, Fisette PL, Denlinger LC (1998) Purinergic receptor modulation of lipopolysaccharide signaling and inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Biol Chem 273:27170–27175 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Guerra AN, Fisette PL, Pfeiffer ZA (2003) Purinergic receptor regulation of LPS-induced signaling and pathophysiology. J Endotoxin Res 9:256–263 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Ferrari D, Pizzirani C, Adinolfi E (2006) The P2X7 receptor: a key player in IL-1 processing and release. J Immunol 176:3877–3883 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hewinson J, Mackenzie AB (2007) P2X(7) receptor-mediated reactive oxygen and nitrogen species formation: from receptor to generators. Biochem Soc Trans 35:1168–1170 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Pfeiffer ZA, Guerra AN, Hill LM (2007) Nucleotide receptor signaling in murine macrophages is linked to reactive oxygen species generation. Free Radic Biol Med 42:1506–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Pfeiffer ZA, Aga M, Prabhu U (2004) The nucleotide receptor P2X7 mediates actin reorganization and membrane blebbing in RAW 264.7 macrophages via p38 MAP kinase and Rho. J Leukoc Biol 75:1173–1182 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Denlinger LC, Fisette PL, Garis KA (1996) Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by macrophage purinoreceptors and calcium. J Biol Chem 271:337–342 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Di Virgilio F, Falzoni S, Chiozzi P (1999) ATP receptors and giant cell formation. J Leukoc Biol 66:723–726 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Baricordi OR, Melchiorri L, Adinolfi E (1999) Increased proliferation rate of lymphoid cells transfected with the P2X(7) ATP receptor. J Biol Chem 274:33206–33208 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Mackenzie AB, Young MT, Adinolfi E (2005) Pseudoapoptosis induced by brief activation of ATP-gated P2X7 receptors. J Biol Chem 280:33968–33976 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Darville T, Welter-Stahl L, Cruz C (2007) Effect of the purinergic receptor P2X7 on Chlamydia infection in cervical epithelial cells and vaginally infected mice. J Immunol 179:3707–30714 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Li CM, Campbell SJ, Kumararatne DS (2002) Association of a polymorphism in the P2X7 gene with tuberculosis in a Gambian population. J Infect Dis 186:1458–1462 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Barden N, Harvey M, Gagne B (2006) Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes in the chromosome 12Q24.31 region points to P2RX7 as a susceptibility gene to bipolar affective disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 141:374–382 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Smart ML, Gu B, Panchal RG (2003) P2X7 receptor cell surface expression and cytolytic pore formation are regulated by a distal C-terminal region. J Biol Chem 278:8853–8860 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Denlinger LC, Fisette PL, Sommer JA (2001) Cutting edge: the nucleotide receptor P2X7 contains multiple protein- and lipid-interaction motifs including a potential binding site for bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 167:1871–1876 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Gu BJ, Zhang W, Worthington RA (2001) A Glu-496 to Ala polymorphism leads to loss of function of the human P2X7 receptor. J Biol Chem 276:11135–11142 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Li CM, Campbell SJ, Kumararatne DS (2002) Response heterogeneity of human macrophages to ATP is associated with P2X7 receptor expression but not to polymorphisms in the P2RX7 promoter. FEBS Lett 531:127–131 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Wiley JS, Dao-Ung LP, Li C (2003) An Ile-568 to Asn polymorphism prevents normal trafficking and function of the human P2X7 receptor. J Biol Chem 278:17108–17113 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Gu BJ, Sluyter R, Skarratt KK (2004) An Arg307 to Gln polymorphism within the ATP-binding site causes loss of function of the human P2X7 receptor. J Biol Chem 279:31287–31295 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Le Stunff H, Auger R, Kanellopoulos J (2004) The Pro-451 to Leu polymorphism within the C-terminal tail of P2X7 receptor impairs cell death but not phospholipase D activation in murine thymocytes. J Biol Chem 279:16918–16926 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Cabrini G, Falzoni S, Forchap SL (2005) A His-155 to Tyr polymorphism confers gain-of-function to the human P2X7 receptor of human leukemic lymphocytes. J Immunol 175:82–89 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Skarratt KK, Fuller SJ, Sluyter R (2005) A 5′ intronic splice site polymorphism leads to a null allele of the P2X7 gene in 1–2% of the Caucasian population. FEBS Lett 579:2675–2678 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Shemon AN, Sluyter R, Fernando SL (2006) A Thr357 to Ser polymorphism in homozygous and compound heterozygous subjects causes absent or reduced P2X7 function and impairs ATP-induced mycobacterial killing by macrophages. J Biol Chem 281:2079–2086 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Denlinger LC, Angelini G, Schell K (2005) Detection of human P2X7 nucleotide receptor polymorphisms by a novel monocyte pore assay predictive of alterations in lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine production. J Immunol 174:4424–4431 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Denlinger LC, Coursin DB, Schell K (2006) Human P2X7 pore function predicts allele linkage disequilibrium. Clin Chem 52:995–1004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Sjoblom T, Jones S, Wood LD (2006) The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science 314:268–274 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Slater M, Danieletto S, Gidley-Baird A (2004) Early prostate cancer detected using expression of non-functional cytolytic P2X7 receptors. Histopathology 44:206–215 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Solini A, Cuccato S, Ferrari D (2008) Increased P2X7 receptor expression and function in thyroid papillary cancer: a new potential marker of the disease. Endocrinol 149:389–396 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Li X, Zhou L, Feng YH (2006) The P2X7 receptor: a novel biomarker of uterine epithelial cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15:1906–1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Zhang XJ, Zheng GG, Ma XT (2004) Expression of P2X7 in human hematopoietic cell lines and leukemia patients. Leuk Res 28:1313–1322 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Li X, Qi X, Zhou L (2007) Decreased expression of P2X7 in endometrial epithelial pre-cancerous and cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol 106:233–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Feng YH, Li X, Wang L (2006) A truncated P2X7 receptor variant (P2X7-j) endogenously expressed in cervical cancer cells antagonizes the full-length P2X7 receptor through hetero-oligomerization. J Biol Chem 281:17228–17237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Di Virgilio F, Chiozzi P, Ferrari D (2001) Nucleotide receptors: an emerging family of regulatory molecules in blood cells. Blood 97:587–600 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Watters J, Sommer J, Fisette P (2001) P2X7 nucleotide receptor: modulation of LPS-induced macrophage signaling and mediator production. Drug Dev Res 53:91–104

- 51.Lister MF, Sharkey J, Sawatzky DA (2007) The role of the purinergic P2X7 receptor in inflammation. J Inflamm 4:5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Noguchi T, Ishii K, Fukutomi H (2008) Requirement of reactive oxygen species-dependent activation of ASK1–p38 MAPK pathway for extracellular ATP-induced apoptosis in macrophage. J Biol Chem 283:7657–7665 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Suh BC, Kim JS, Namgung U (2001) P2X7 nucleotide receptor mediation of membrane pore formation and superoxide generation in human promyelocytes and neutrophils. J Immunol 166:6754–6763 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Di Virgilio F, Chiozzi P, Falzoni S (1998) Cytolytic P2X purinoceptors. Cell Death Differ 5:191–199 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Stefano L, Rossler OG, Griesemer D (2007) P2X(7) receptor stimulation upregulates Egr-1 biosynthesis involving a cytosolic Ca(2+) rise, transactivation of the EGF receptor and phosphorylation of ERK and Elk-1. J Cell Physiol 213:36–44 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Guerra AN, Gavala ML, Chung HS (2007) Nucleotide receptor signalling and the generation of reactive oxygen species. Purinergic Signal 3:39–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Denu JM, Tanner KG (1998) Specific and reversible inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases by hydrogen peroxide: evidence for a sulfenic acid intermediate and implications for redox regulation. Biochem 37:5633–5642 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Guyton KZ, Liu Y, Gorospe M (1996) Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by H2O2. Role in cell survival following oxidant injury. J Biol Chem 271:4138–4142 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Iles KE, Dickinson DA, Watanabe N (2002) AP-1 activation through endogenous H(2)O(2) generation by alveolar macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med 32:1304–1313 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Kaul N, Forman HJ (1996) Activation of NF kappa B by the respiratory burst of macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med 21:401–405 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Lander HM (1997) An essential role for free radicals and derived species in signal transduction. FASEB J 11:118–124 [PubMed]

- 62.Lee K, Esselman WJ (2002) Inhibition of PTPs by H(2)O(2) regulates the activation of distinct MAPK pathways. Free Radic Biol Med 33:1121–1132 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Lo YY, Wong JM, Cruz TF (1996) Reactive oxygen species mediate cytokine activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases. J Biol Chem 271:15703–15707 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Curtin JF, Donovan M, Cotter TG (2002) Regulation and measurement of oxidative stress in apoptosis. J Immunol Methods 265:49–72 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Pines A, Perrone L, Bivi N (2005) Activation of APE1/Ref-1 is dependent on reactive oxygen species generated after purinergic receptor stimulation by ATP. Nucleic Acids Res 33:4379–4394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Adler V, Yin Z, Tew KD (1999) Role of redox potential and reactive oxygen species in stress signaling. Oncogene 18:6104–6111 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Ferrari D, Wesselborg S, Bauer MK (1997) Extracellular ATP activates transcription factor NF-kappaB through the P2Z purinoreceptor by selectively targeting NF-kappaB p65. J Cell Biol 139:1635–1643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Aga M, Watters JJ, Pfeiffer ZA (2004) Evidence for nucleotide receptor modulation of cross talk between MAP kinase and NF-kappa B signaling pathways in murine RAW 264.7 macrophages. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286:C923–C930 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Aga MJ, Johnson CJ, Hart AP (2002) Modulation of monocytes signaling and pore formation in response to agonists of the nucleotide receptor P2X7. J Leukoc Biol 72:222–232 [PubMed]

- 70.Di Virgilio F (1995) The P2Z purinoceptor: an intriguing role in immunity, inflammation and cell death. Immunol Today 16:524–528 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Ferrari D, Chiozzi P, Falzoni S (1997) ATP-mediated cytotoxicity in microglial cells. Neuropharmacology 36:1295–1301 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Grahames CB, Michel AD, Chessell IP (1999) Pharmacological characterization of ATP- and LPS-induced IL-1beta release in human monocytes. Br J Pharmacol 127:1915–1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Griffiths RJ, Stam EJ, Downs JT (1995) ATP induces the release of IL-1 from LPS-primed cells in vivo. J Immunol 154:2821–2828 [PubMed]

- 74.Solle M, Labasi J, Perregaux DG (2001) Altered cytokine production in mice lacking P2X(7) receptors. J Biol Chem 276:125–132 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Tonetti M, Sturla L, Bistolfi T (1994) Extracellular ATP potentiates nitric oxide synthase expression induced by lipopolysaccharide in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 203:430–435 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Tonetti M, Sturla L, Giovine M (1995) Extracellular ATP enhances mRNA levels of nitric oxide synthase and TNF-alpha in lipopolysaccharide-treated RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 214:125–130 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Cassatella MA, Bazzoni F, Flynn RM (1990) Molecular basis of interferon-gamma and lipopolysaccharide enhancement of phagocyte respiratory burst capability. Studies on the gene expression of several NADPH oxidase components. J Biol Chem 265:20241–20246 [PubMed]

- 78.Quinn MT, Gauss KA (2004) Structure and regulation of the neutrophil respiratory burst oxidase: comparison with nonphagocyte oxidases. J Leukoc Biol 76:760–781 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Sheppard FR, Kelher MR, Moore EE (2005) Structural organization of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase: phosphorylation and translocation during priming and activation. J Leukoc Biol 78:1025–1042 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.DeLeo FR, Renee J, McCormick S (1998) Neutrophils exposed to bacterial lipopolysaccharide upregulate NADPH oxidase assembly. J Clin Invest 101:455–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Vignais PV (2002) The superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase: structural aspects and activation mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci 59:1428–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Decoursey TE, Ligeti E (2005) Regulation and termination of NADPH oxidase activity. Cell Mol Life Sci 62:2173–2193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Groemping Y, Rittinger K (2005) Activation and assembly of the NADPH oxidase: a structural perspective. Biochem J 386:401–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Budagian V, Bulanova E, Brovko L (2003) Signaling through P2X7 receptor in human T cells involves p56lck, MAP kinases, and transcription factors AP-1 and NF-kappa B. J Biol Chem 278:1549–1560 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 85.Armstrong S, Korcok J, Sims SM (2007) Activation of transcription factors by extracellular nucleotides in immune and related cell types. Purinergic Signal 3:59–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Franco-Martinez S, Nino-Moreno P, Bernal-Silva S (2006) Expression and function of the purinergic receptor P2X7 in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol 146:253–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME (1999) CREB: a stimulus-induced transcription factor activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals. Annu Rev Biochem 68:821–861 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 88.Mayr B, Montminy M (2001) Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2:599–609 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Potucek YD, Crain JM, Watters JJ (2006) Purinergic receptors modulate MAP kinases and transcription factors that control microglial inflammatory gene expression. Neurochem Int 49:204–214 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 90.Desmet C, Gosset P, Henry E (2005) Treatment of experimental asthma by decoy-mediated local inhibition of activator protein-1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172:671–678 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 91.Guo RF, Lentsch AB, Sarma JV (2002) Activator protein-1 activation in acute lung injury. Am J Pathol 161:275–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Padeh S, Cohen A, Roifman CM (1991) ATP-induced activation of human B-lymphocytes via P2-purinoceptors. J Immunol 146:1626–1632 [PubMed]

- 93.John GR, Simpson JE, Woodroofe MN (2001) Extracellular nucleotides differentially regulate interleukin-1beta signaling in primary human astrocytes: implications for inflammatory gene expression. J Neurosci 21:4134–4142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Liu JS, John GR, Sikora A (2000) Modulation of interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor alpha signaling by P2 purinergic receptors in human fetal astrocytes. J Neurosci 20:5292–5299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Humphreys BD, Rice J, Kertesy SB (2000) Stress-activated protein kinase/JNK activation and apoptotic induction by the macrophage P2X7 nucleotide receptor. J Biol Chem 275:26792–26798 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 96.Denlinger LC, Sommer JA, Parker K (2003) Mutation of a dibasic amino acid motif within the C terminus of the P2X7 nucleotide receptor results in trafficking defects and impaired function. J Immunol 171:1304–1311 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Fernando SL, Saunders BM, Sluyter R (2005) Gene dosage determines the negative effects of polymorphic alleles of the P2X7 receptor on adenosine triphosphate-mediated killing of mycobacteria by human macrophages. J Infect Dis 192:149–155 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 98.Michelsen K, Yuan H, Schwappach B (2005) Hide and run. Arginine-based endoplasmic-reticulum-sorting motifs in the assembly of heteromultimeric membrane proteins. EMBO Rep 6:717–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Margeta-Mitrovic M, Jan YN, Jan LY (2000) A trafficking checkpoint controls GABA(B) receptor heterodimerization. Neuron 27:97–106 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 100.Standley S, Roche KW, McCallum J (2000) PDZ domain suppression of an ER retention signal in NMDA receptor NR1 splice variants. Neuron 28:887–898 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 101.Schutze MP, Peterson PA, Jackson MR (1994) An N-terminal double-arginine motif maintains type II membrane proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J 13:1696–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.Zerangue N, Schwappach B, Jan YN (1999) A new ER trafficking signal regulates the subunit stoichiometry of plasma membrane K(ATP) channels. Neuron 22:537–548 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Ren Z, Riley NJ, Needleman LA (2003) Cell surface expression of GluR5 kainate receptors is regulated by an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal. J Biol Chem 278:52700–52709 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 104.Hou JC, Pessin JE (2007) Ins (endocytosis) and outs (exocytosis) of GLUT4 trafficking. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19:466–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 105.Korpi-Steiner NL, Bates ME, Lee WM (2006) Human rhinovirus induces robust IP-10 release by monocytic cells, which is independent of viral replication but linked to type I interferon receptor ligation and STAT1 activation. J Leukoc Biol 80:1364–1374 [DOI] [PubMed]