Abstract

Background and purpose

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most common form of vertigo. Although the repositioning maneuver dramatically improves the vertigo, some patients complain of residual dizziness. We evaluated the incidence and characteristics of persistent dizziness after successful particle repositioning and the clinical factors associated with the residual dizziness.

Methods

We performed a prospective investigation in 49 consecutive patients with confirmed BPPV. The patients were treated with a repositioning maneuver appropriate for the type of BPPV. Success was defined by the resolution of nystagmus and positional vertigo. All patients were followed up until complete resolution of all dizziness, for a maximum of 3 months. We collected data on the characteristics and duration of any residual dizziness and analyzed the clinical factors associated with the residual dizziness.

Results

Of the 49 patients, 11 were men and 38 were women aged 60.4±13.0 years (mean ±SD), and 30 (61%) of them complained of residual dizziness after successful repositioning treatment. There were two types of residual dizziness: continuous lightheadedness and short-lasting unsteadiness occurring during head movement, standing, or walking. The dizziness lasted for 16.4±17.6 days (range=2-80 days, median=10 days). A longer duration of BPPV before treatment was significantly associated with residual dizziness (p=0.04).

Conclusions

Residual dizziness after successful repositioning was observed in two-thirds of the patients with BPPV and disappeared within 3 months without specific treatment in all cases. The results indicate that early successful repositioning can reduce the incidence of residual dizziness.

Keywords: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Dizziness, Repositioning maneuver

Introduction

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most common cause of vertigo.1,2 The diagnosis is confirmed by provocation maneuvers, such as the Dix-Hallpike test3,4 or the supine head-turning test,5 and repositioning maneuvers represent an effective therapy. Although the repositioning maneuvers usually dramatically improve the vertigo, some patients report residual dizziness. This study evaluated the incidence and characteristics of residual dizziness after successful particle repositioning and to determine the predictors of this condition.

Methods

A prospective study was performed in 49 consecutive patients with confirmed BPPV from March to October 2007. The diagnosis was based on a history of recurrent positional vertigo and the results of the Dix-Hallpike and supine head-turning tests. The Dix-Hallpike test was considered positive if nystagmus was recorded with appropriate positioning, latency, duration, and fatigue, and reversed when the patient resumed a sitting position. With the affected ear down, geotropic torsional nystagmus (i.e., the upper poles of the eyes beating to the lowermost ear) occurs with an up-beating component for the posterior canal (PC) and a down-beating component for the anterior canal (AC). Horizontal canal (HC) BPPV was diagnosed by horizontal direction-changing positional nystagmus concurrent with vertigo elicited by the supine head-turning test. Patients were divided into canalolithiasis and cupulolithiasis groups according to the direction of the nystagmus.

We collected information on demographic characteristics, the clinical features of the BPPV, the history of BPPV, and concurrent diseases, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, and hyperlipidemia. The clinical features of BPPV include the affected side, involved canal, duration of vertigo, total number of vertigo attacks before treatment, and cause of BPPV. The duration of vertigo was defined as the duration from the first episode to successful treatment (i.e., not the duration of a single vertigo episode). We identified the etiology of BPPV as idiopathic, vestibular neuronitis (patients with a history of acute vestibulopathy on the affected side), or traumatic. The etiology was considered traumatic if the symptoms appeared within 1 week after head trauma. The information was collected in a structured interview with the patients and using videooculography.

The patients were treated with the repositioning maneuver appropriate for the type of BPPV.6-9 Patients with PC BPPV were treated with the maneuver described by Epley.8 After this maneuver, we suggested self-treatment using the Brand-Daroff exercise to these patients. The reverse Epley maneuver and barbecue rotation were used for patients with AC and HC BPPV, respectively. After the maneuver, we suggested to patients that they lie on the healthy side during the following night. For patients with lateral canal cupulolithiasis, we recommended a mastoid vibrator or Brand-Daroff exercise to detach debris before applying the repositioning maneuver. The maneuver was performed several times until repositioning was successful, defined as the absence of nystagmus and positional vertigo. The success was determined 2 or 3 days after the treatment (at the next follow-up in the outpatient department) based on the result of the positioning test. If the positioning test was negative, we collected information on the presence of any residual dizziness and its characteristics at that time, and followed up the patient every week. All of the patients were followed up until complete resolution of any dizziness (for a maximum of 3 months) via interviews at the outpatient clinic or by telephone. The outcome was classified as complete or partial recovery, with the latter referring to persistent residual dizziness without vertigo after repositioning.

We compared the characteristics of the patients between those with complete recovery and those with partial recovery using the independent-samples t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify significant variables adjusted for multiple risk factors. We assessed the duration for complete resolution of residual dizziness using the Kaplan-Meier survival curve. All analyses were performed using SPSS 11.0 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

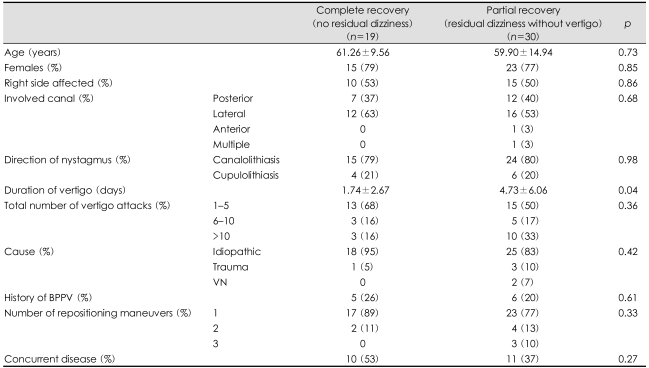

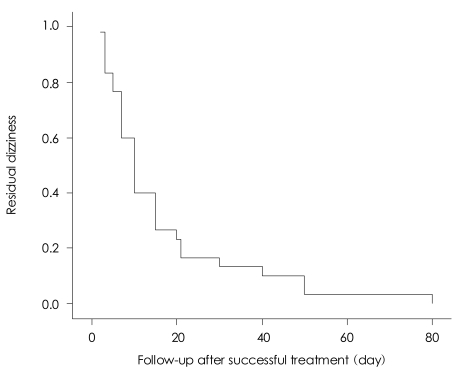

Forty-nine patients were enrolled in this prospective study, comprising 11 men and 38 women aged 60.4±13.0 years (mean±SD; range=34-88 years). The PC, HC, and AC were involved in 19, 28, and 1 patient, respectively, with both the PC and HC involved in the remaining patient (Table 1). Thirty (61%) of the patients complained of residual dizziness after successful repositioning, which was characterized by continuous or intermittent lightheadedness: 18 patients had continuous lightheadedness, 8 had intermittent unsteadiness, and 4 had both types of dizziness. The dizziness lasted for 16.4±17.6 days (range=2-80 days, median=10 days). Fig. 1 shows the cumulative fractions of residual nonspecific dizziness during the 3 months follow-up. The residual dizziness subsided within 20 days in most patients, and none had dizziness 3 months later. In univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis, a longer duration of BPPV was significantly associated with residual dizziness after successful repositioning (p=0.04). Only the duration of BPPV was a significant predicting factor (OR=1.27, 95% CI=1.01-1.59). The other demographic and clinical parameters were not significantly related to the outcome.

Table 1.

Demographics, clinical features, and concurrent diseases in the patients

BPPV: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, VN: vestibular neuronitis

Fig. 1.

Cumulative fractions of residual dizziness during the follow-up after successful repositioning. The residual dizziness subsided within 20 days in most patients.

Discussion

Two-thirds of the patients included in this study complained of residual dizziness after successful repositioning. Although the description (usual description of the dizziness) alone does not distinguish different types of dizziness, certain terms are commonly used to describe each type of dizziness. In this study, the residual dizziness could be classified as non-vestibular dizziness, based on the characteristics of the residual dizziness and the absence of nausea and vomiting. However, a sensation of spinning does not always indicate a vestibular disorder, and nonvertiginous dizziness does not always mean nonvestibular disorder. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the origin of residual dizziness from only its characteristics.

There are four possible explanations for persistent residual dizziness after successful treatment. First, remaining otoconial debris due to incomplete repositioning could produce mild positional vertigo, where the remaining debris is insufficient to deflect the cupula to a degree sufficient to provoke overt nystagmus.10 Second, BPPV is not only a disorder of the semicircular canals but also a disorder of the otoliths that sense orientation in space, and otolith dysfunction might account for transient mild dizziness.11,12 Third, another vestibular lesion-which is difficult to identify from the history alone-might coexist with BPPV. A previous study found that the prevalence of less-specific persistent dizziness was significantly higher in patients with BPPV and additional peripheral or central vestibular dysfunction.13 Fourth, delayed recovery might be due to the longer time needed for central adaptation after particle repositioning.

We found that a longer duration of BPPV was associated with the presence of residual dizziness after the particle repositioning maneuver. A previous study also showed that the severity of postural instability estimated after repositioning maneuver depended on the disease duration of BPPV.14 These findings indicate that early recognition and treatment will reduce the incidence of residual dizziness in patients with BPPV.

References

- 1.Baloh RW, Honrubia V, Jacobson K. Benign positional vertigo: clinical and oculographic features in 240 cases. Neurology. 1987;37:371–378. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nedzelski JM, Barber HO, McIlmoyl L. Diagnoses in a dizziness unit. J Otolaryngol. 1986;15:101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dix MR, Hallpike CS. The pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Proc R Soc Med. 1952;45:341–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herdman SJ, Tusa RJ, Clendaniel RA. Eye movement signs in vertical canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. In: Fuchs AF, Brandt T, Buttner U, Zee D, et al., editors. Contemporary Ocular Motor and Vestibular Research: a Tribute to David A Robinson Stuttgart. Germany: Georg Thieme; 1994. pp. 385–387. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baloh RW, Jacobson K, Honrubia V. Horizontal semicircular canal variant of benign positional vertigo. Neurology. 1993;43:2542–2549. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.12.2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lempert T, Tiel-Wilck K. A positional maneuver for treatment of horizontal-canal benign positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:476–478. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199604000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuti D, Agus G, Barbieri MT, Passali D. The management of horizontal-canal paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998;118:455–460. doi: 10.1080/00016489850154559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epley J. The canalith repositioning procedure for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:399–404. doi: 10.1177/019459989210700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herdman SJ. Advances in the treatment of vestibular disorders. Phys Ther. 1997;77:602–618. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.6.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Girolamo S, Ottaviani F, Scarano E, Picciotti P, Di Nardo W. Postural control in horizontal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;257:372–375. doi: 10.1007/s004050000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Brevern M, Schmidt T, Schönfeld U, Lempert T, Clarke AH. Utricular dysfuction in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:92–96. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000187238.56583.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gall RM, Ireland DJ, Robertson DD. Subjective visual vertical in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Otolaryngol. 1999;28:162–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollak L, Davies RA, Luxon LL. Effectiveness of the particle repositioning maneuver in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with and without additional vestibular pathology. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:79–83. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200201000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stambolieva K, Angov G. Postural stability in patients with different durations of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:118–122. doi: 10.1007/s00405-005-0971-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]