Abstract

Prophylactic strategies against hepatitis B virus (HBV) recurrence after liver transplantation (LT) are essential for patients with HBV-related disease. Before LT, lamivudine (LAM) was proposed to be down-graded from first- to second-line therapy. In contrast, adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) has been approved not only as first-line therapy but also as rescue therapy for patients with LAM resistance. Furthermore, combination of ADV and LAM may result in lower risk of ADV resistance than ADV monotherapy. Other new drugs such as entecavir, telbivudine and tenofovir, are probably candidates for the treatment of hepatitis-B-surface-antigen-positive patients awaiting LT. After LT, low-dose intramuscular hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG), in combination with LAM, has been regarded as the most cost-effective regimen for the prevention of post-transplant HBV recurrence in recipients without pretransplant LAM resistance and rapidly accepted in many transplant centers. With the introduction of new antiviral drugs, new hepatitis B vaccine and its new adjuvants, post-transplant HBIG-free therapeutic regimens with new oral antiviral drug combinations or active HBV vaccination combined with adjuvants will be promising, particularly in those patients with low risk of HBV recurrence.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, Liver transplantation, Recurrence, Prophylaxis, Hepatitis B immunoglobulin

INTRODUCTION

End-stage liver disease secondary to hepatitis B virus (HBV) accounts for 5%-10% of liver transplantation (LT) performed in the United States and is the leading indication for LT in Asia[1,2]. Recurrence of HBV infection after LT plays a key role in the post-transplant outcomes of the patient and graft, however, in patients with HBV-related disease, complete eradication of HBV after LT is rarely possible. In the 1980s, HBV-related disease was considered a relative contraindication for LT because of poor survival rate and high recurrence rate of HBV in the absence of prophylactic strategies[3]. Thus, prophylactic strategies against HBV recurrence after LT are essential for these recipients. Since the introduce of new antiviral agents and improved prophylactic options, results after LT are reported to be as good or, in a United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database report, even better than in non-HBV patients[4,5]. In this article, current prophylactic strategies against HBV recurrence after LT and evolving new trends are reviewed.

PRETRANSPLANTATION PROPHYLACTIC STRATEGIES

The goals of pretransplant antiviral therapy include the following: (1) to achieve clinical stabilization, thereby delaying/preventing the need for LT; and (2) to attain low HBV DNA levels prior to transplantation, thereby reducing the risk of recurrent HBV after LT.

Interferon (IFN)

Although a major limitation to the use of IFN before LT has been its poor tolerability, it appears to be reasonably well tolerated and effective if patients do not have decompensated HBV cirrhosis. Hoofnagle et al[6] have reported that IFN-α therapy stabilized liver function and achieved a sustained loss of HBV DNA and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) in 6 of 18 compensated cirrhotic patients. A prospective study also confirmed that 53 of 103 patients with IFN-α therapy no longer had detectable HBV DNA or HBeAg after a median follow-up of 50 mo[7]. Tchervenkov et al[8] also found that pretransplantation IFN therapy followed by hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) after transplantation was associated with only an 8% recurrence rate after a median follow-up of 32 mo. In addition, a recent study revealed that adjuvant IFN therapy improved the 5-year survival of patients with HBV-related hepatocelluar carcinoma (HCC)[9]. Some data are currently available on the use of peg-interferon α-2b in cirrhosis patients with HBV, after being approved by the US FDA for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Chan et al[10] have demonstrated that combination treatment of peg-interferon and lamivudine (LAM) led to a higher sustained loss of HBeAg than LAM monotherapy up to 3 years after therapy. Notably, HBeAg or hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss is observed more frequently in patients infected with HBV genotype A than with genotype non-A[11,12]. However, the risks associated with IFN therapy and the emergence of safe and well-tolerated oral antiviral therapies have decreased the utility of IFN therapy in patients undergoing LT.

Famciclovir (FCV)

FCV is a guanosine nucleoside analog with activity against herpes viruses and HBV[13]. Several reports[13,14] have described efficacy of FCV in patients with recurrent HBV after LT. However, the number of reports concerning pretransplant application of FCV is limited and the outcome of this pretransplantation prophylactic strategy is not satisfactory. Singh et al[15] have found that only 25% of the patients with detectable HBV DNA became pretransplant HBV-DNA-negative after using FCV. Seehofer et al[16] also found, in a retrospective study that included 74 HBV-DNA positive patients, that pretransplant FCV did not seem to significantly reduce post-transplant HBV recurrence. Therefore, FCV is rarely used before LT.

LAM

LAM is the first nucleoside analog, a potent inhibitor of HBV replication by competitive inhibition of the reverse transcriptase and termination of proviral DNA chain extension, to be approved for use in HBV treatment, and has an excellent safety profile in both compensated and decompensated cirrhotic patients. The early results using LAM as pretransplant antiviral therapy to suppress HBV replication and improve liver function were promising. Two studies from Villeneuve et al[17] and Yao et al[18] have reported that serum HBV DNA of all case with positive HBV DNA became undetectable after 6 mo of LAM therapy. The same results were confirmed by other studies[19–21]. These data indicated that LAM monotherapy can achieve the goal of suppression of viral replication to undetectable HBV DNA levels prior to transplantation, and improvement of liver function.

However, the major factor limiting the use of LAM is the development of mutations in the thyrosine-methionine-aspartate-aspartate (YMDD) motif of the HBV DNA polymerase gene, which confers resistance to LAM. In non-immunosuppressed patients, resistance to LAM emerges at a rate of 15%-20% per year, as a result of selection of LAM-resistant mutations in the YMDD motif of the HBV DNA polymerase[22]. As for immunosuppressed patients, LAM resistance can be detected in 45% patients within the first treatment year[23,24]. The sign of resistance is usually a rebound in the HBV DNA level, without other abnormal biochemical or clinical findings, whereas some virological breakthrough caused by antiviral resistance has been reported to cause hepatitis flares and, in rare instances, hepatic decompensation[25,26]. In addition, a retrospective analysis of 309 HBsAg-positive patients listed for LT at 20 North American transplant centers revealed that LAM did not improve LT-free and overall pretransplant survival[27]. LAM is even proposed to be no longer the drug of choice because the initial enthusiasm has been tempered by the high rate of resistance development[28].

Overall, LAM has provided an important treatment option in these patients on the waiting list, with evidence of viral replication or decompensated liver disease related to HBV, but it has turned out not to be the optimal drug and has been proposed to be down-graded from first- to second-line therapy because of its resistance profile.

Adefovir dipivoxil (ADV)

ADV is an oral prodrug of adefovir, a nucleotide analog of AMP, which inhibits HBV DNA polymerase. Previous studies have demonstrated that ADV has excellent activity against wild-type as well as LAM-resistant HBV strains[29–32]. Recently, Marcellin et al[33] used ADV administered at doses of 10 mg daily over 48 wk in 171 patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. At week 48, the median change from baseline in HBV DNA was -3.44 log10 copies/mL. Subsequently, 65 patients given ADV 10 mg in year 1 chose to continue in a long-term safety and efficacy study (5 years). The median serum HBV DNA changes from baseline were -2.15, -3.69, -3.55 and -4.05 log10 copies/mL at study weeks 96, 144, 192 and 240, respectively. The median change values from baseline in serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations were -43, -18, -49.5, -41 and -50 IU/L at study weeks 48, 96, 144, 192 and 240, respectively, and 66% had normalized serum ALT concentrations at study week 240. As for the resistance to ADV, in the 65 patients with a median of 235 wk (110-279 wk) of ADV exposure, 13 (20%) had developed ADV-associated resistance mutations, rt N236T or rtA181V. The first resistance mutation was observed after 135 wk of ADV. In addition, there were no serious adverse events related to ADV. The safety and efficacy of ADV were also confirmed by other studies[34,35].

Thus, ADV has been approved not only as a first-line therapy but also as a rescue therapy for patients with LAM resistance.

ADV and LAM combination therapy

Many of the anti-HBV drugs were initially developed for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Resistance develops easily during HIV monotherapy, therefore, it would make theoretical sense that this would also be seen with HBV. The lessons from the HIV field indicate that combination therapy is the way to go, however, we need studies for this in an HBV setting. The above data clearly indicate that ADV monotherapy is effective and safe in waiting-list chronic hepatitis B patients, with or without LAM-resistant HBV, and has much lower rates of resistance than LAM. How effective is ADV and LAM combination therapy in LAM-resistant chronic hepatitis B patients? The latest results[36–39] of ADV alone or in combination with LAM in LAM-resistant chronic hepatitis B are summarized in Table 1. ADV administered in combination with LAM or as monotherapy appeared to be effective in durable suppression of HBV replication and normalization of liver enzymes, and no significant difference was found between these two groups. This result is in accord with the data from a previous study[40], which showed that serum HBV DNA decreased at a similar rate in patients with compensated liver disease and LAM-resistant HBV infection, randomized to ADV monotherapy or combination of ADV and LAM. In addition, one recent study found that short-term (approximately 2 mo) overlap LAM treatment resulted in no better virological and biological outcomes than non-overlap ADV[41]. However, the data concerning incidence of ADV resistance between two groups are controversial. On the one hand, some studies have suggested that there is no obvious improvement in reduction in the development of ADV resistance with ADV alone compared with ADV in combination with LAM[38,39], but one study was limited by its open-label, non-randomized, uncontrolled, retrospective design, and the other study was limited by its short-term follow-up. On the other hand, several recent studies[36,37] have shown that combination of ADV and LAM results in lower risk of ADV resistance than ADV monotherapy. Notably, one was a prospective, randomized controlled study with a small population. Additionally, the same result has been confirmed by other studies[42].

Table 1.

ADV monotherapy vs ADV/LAM combination therapy in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B

| Ref. |

Patients (n) |

Undetectable HBV DNA |

Follow up |

P |

Normalization of ALT |

Follow up |

P |

ADV resistance |

Follow-up |

P | ||||

| A | AL | A (%) | AL (%) | A (%) | AL (%) | A (%) | AL (%) | |||||||

| [36] | 14 | 28 | 79 | 89 | At month 36 | 0.26 | 73 | 91 | At month 24 | 0.69 | 21 | 0 | At month 36 | 0.020 |

| [37] | 23 | 36 | 82 | 89 | At month 24 | > 0.50 | 53 | 79 | At month 24 | > 0.50 | 22 | 0 | At month 24 | 0.001 |

| [38] | 28 | 28 | 64 | 40 | At month 24 | 0.38 | 80 | 74 | At month 12 | 0.72 | 18 | 7 | At month 24 | 0.940 |

| [39] | 34 | 36 | 82 | 97 | At month 12 | > 0.50 | 79 | 96 | At month 12 | > 0.50 | 18 | 3 | At month 12 | > 0.500 |

A: ADV monotherapy; AL: ADV/LAM combination therapy.

Overall, some of the studies on combination therapy were too short in terms of follow-up, such that differences between monotherapy and combination therapy are not easily distinguished. Thus, long-term, randomized, blinded, controlled clinical trials are still required to determine whether ADV and LAM combination therapy reduces the emergence of ADV resistance compared with ADV monotherapy.

Entecavir

Entecavir is a very potent anti-HBV selective guanosine analog and was approved by the US FDA in 2005, for the management of adult patients with chronic HBV infection. Two early studies[43,44] have suggested that the rates of histological, virological and biochemical improvement, among patients with nucleoside-naive HBeAg-positive or -negative chronic hepatitis B, are significantly higher with entecavir than with LAM, and there is no evidence of viral resistance to entecavir. In addition, several recent studies[45,46] further reinforced this result and a recent randomized international study even found that entecavir therapy resulted in earlier and superior reduction in HBV DNA compared with ADV, in nucleoside-naive HBeAg-positive patients with chronic hepatitis B[47].

Entecavir resistance is associated with the LAM-resistance substitutions M204V/I and L180M, in combination with an additional substitution at residues T184, S202 or M250 in the reverse-transcriptase region of HBV polymerase[48]. In other words, entecavir is associated with a high genetic barrier to resistance that requires multiple mutations for resistance to emerge. In nucleoside-naïve patients, the probability of developing resistance to entecavir remained consistently low (< 1.2%) even after 96 wk of therapy[49]. In contrast, entecavir administration in patients with LAM resistance gives rise to entecavir-resistant mutants. The rate of entecavir resistance after 4 years of treatment of LAM-resistant patients may reach 35%[50]. This results from a particular mode of selection of entecavir strains that follows a two-step process, with the selection of primary resistance mutations at position M204V/I (which are also resistant to LAM), followed by the addition of secondary resistance mutations to the same viral genomes[51]. Once these secondary substitutions occur, high-level resistance to entecavir occurs.

Generally speaking, as a result of its potency and unique structural formula, entecavir monotherapy represents an interesting first-line treatment option in patients with nucleoside-naive HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B, but for LAM-refractory HBV patients, entecavir monotherapy does not appear to be the optimal choice because of the high rate of resistance. To date, there are no specific data available on the use of entecavir in patients in association with LT. Further studies are needed to determine its efficacy and safety profile in this special environment.

Other new antiviral drugs

Telbivudine, which was licensed by the US FDA in 2006, is an oral nucleoside analog with potent and specific anti-HBV activity. It has been demonstrated to be superior to LAM in suppressing HBV DNA in both HBeAg-positive and -negative patients, with less resistance[52–54]. M204I was the only signature mutation associated with telbivudine resistance, in contrast to LAM resistance, which is associated with either the M204I or the M204V mutation. Notably, telbivudine can be used against ADV-resistant mutants. Tenofovir is a nucleotide analog and a potent inhibitor of HIV type 1 reverse transcriptase and HBV polymerase. It was recently approved for the treatment of chronic HBV infection in the United States. Marcellin et al[55] reported two studies that compared the antiviral efficacy of tenofovir with that of ADV in both HBeAg-negative and -positive patients. Two of the most encouraging aspects of these two studies are the efficacy of tenofovir in patients with LAM resistance, and the absence of resistance mutations up to week 48. In the treatment of patients with LAM-resistant HBV, tenofovir is superior to ADV and entecavir, and it has a much lower renal toxicity than ADV[56].

However, because of short-term follow up in these studies, cumulative resistance is likely to increase as therapy is extended. Thus, long-term studies are needed to evaluate the safety and resistance of these new antiviral drugs.

POST-TRANSPLANTATION PROPHYLACTIC STRATEGIES

HBIG monotherapy

HBIG was the first agent to show efficacy in preventing HBV recurrence. In 1987, the Hannover group reported that HBIG, to maintain a serum anti-HBs level > 100 IU/L for a minimum of 6 mo after LT, prevented HBV reinfection in liver-transplant recipients[57]. These results were substantiated by a landmark multicenter study from Samuel et al[58] in 1993, in which the 3-year actuarial risk of recurrent HBV infection was 75% ± 6% in patients without immunoprophylaxis, 74% ± 5% in those with short-term immunoprophylaxis (2 mo) and 36% ± 4% in those with long-term HBIG prophylaxis (> 6 mo). In a phase 1 clinical study in 2002[59], promising results using a mixture of two monoclonal antibodies to HBV were obtained. A number of mechanisms, which include binding to circulating virions, blocking an HBV receptor on hepatocytes, and promoting antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity with lysis of infected hepatocytes, have been proposed to explain the protective effects of HBIG[60,61].

In general, high doses of HBIG (10 000 IU) in the anhepatic phase are followed by daily dosing during the first week after transplantation, and subsequent treatment varies at different centers. Fixed and variable dosing schedules as well as intravenous (IV) and intramuscular (IM) administration have been used[61,62]. A pharmacokinetic study indicated that maintaining anti-HBs titers at > 500 IU/L during the first week post-transplantation, > 250 IU/L during weeks 2-12, and > 100 IU/L after week 12 minimized the risk of recurrence[63].

Despite the successful prophylaxis against HBV recurrence after LT, there are several drawbacks to the use of HBIG. (1) Its high cost, namely up to $100 000 in the first year and $40 000 to $50 000 each year thereafter[64]. (2) Its limited supply. (3) Its side effects. Although HBIG is well-tolerated, significant side effects have been noted, including headache, flushing and chest pain[62]. (4) Escape mutants. Reinfection of HBV in patients receiving long-term use of HBIG can occur because of the development of escape mutants. Mutations in the pre S/S region of the HBV genome can lead to an alteration in the “a” determinant of HBsAg, the primary region of HBV antibody binding, which results in reduced efficacy of HBIG[65–67].

As a result of the above shortcomings of HBIG and the introduction of nucleoside or nucleotide analogs, HBIG monotherapy has vanished from prophylaxis against HBV recurrence after LT. However, HBIG monotherapy may be advocated in some special circumstances. For instance, a recent retrospective study of 639 HBV-infected adult patients undergoing living donor liver transplantation has demonstrated that high-dose HBIG monotherapy resulted in a 5-year HBV recurrence rate of 7.3%[68]. Both Lee et al[69] and Takemura et al[70] have used HBIG monotherapy as post-transplant prophylaxis against HBV recurrence for patients who received HBsAg-negative/HB core antibody (HBcAb)-positive allografts, with zero recurrence.

LAM monotherapy

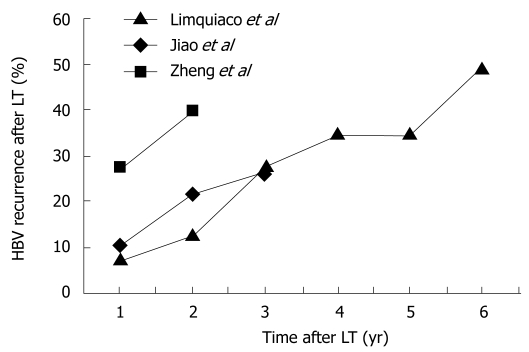

LAM monotherapy was the mainstay of prevention of recurrent HBV after LT in the late 1990s and early 2000. Unfortunately, the initial enthusiasm was tempered by the realization that long-term use of LAM, which is essential for maintaining post-transplant viral suppression, is associated with increasing rates of HBV recurrence as a result of drug resistance. Furthermore, immunosuppression has a great influence on drug resistance; LAM resistance was detected in 15% of immunocompetent patients within the first treatment year compared with 45% in immunosuppressed patients[23,24]. In early studies, post-transplant HBV recurrence has been reported to be 10% by Grellier et al[71], 24% by Lo et al[72], 41% by Perrillo et al[73], and 50% by Mutimer et al[74] at 12, 16, 36 and 36 mo after LT, respectively. Other recent studies with LAM monotherapy have been disappointing with 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, 5- and 6-year recurrence rates of 8%-27%, 13%-40%, 26%-28%, 35%, 35% and 49%, respectively (Figure 1)[75–77]. As a result of the high rate of LAM resistance and higher risk of recurrence in the graft compared with the combination of LAM and HBIG after LT, this strategy has been abandoned. However, whether combination therapy is required in all patients is unknown. LAM monotherapy has still been advocated by some authors for patients who have received HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive allografts, or patients who are HBeAg-negative and have undetectable HBV DNA pretransplantation, because of the low risk of recurrence[73,78,79]. Thus, these patients may be candidates for post-transplant prophylaxis using LAM monotherapy, but further studies with long-term follow-up and a large cohort of patients are necessary to evaluate its efficacy and safety.

Figure 1.

Incidence of recurrent HBV infection after LT using LAM monotherapy as post-transplant prophylaxis. Data adapted from[75–77].

High-dose IV HBIG and LAM combination therapy

The use of combination therapy has become a common strategy to overcome the high recurrence rates observed in patients receiving HBIG or LAM alone[80,81]. Mechanisms contributing to the efficacy of this regimen are not well understood, and may be the consequence of the dual effects of reduced production of HBsAg with antiviral therapy, as well as a decreased rate of escape mutations in the pre-S/S and polymerase regions. Combination therapy with high-dose IV HBIG and LAM has been investigated by many centers[82–86], with encouraging outcomes, in that the HBV recurrence rate is < 10% with 1-2 years follow-up. Generally speaking, LAM is commenced pretransplantation, with the aim of reducing the viral load in the peritransplantation period. IV HBIG is given at a dose of 10 000 IU/d for the first postoperative week, and subsequently at a fixed dose of 10 000 IU/mo or with variable dosing to maintain trough anti-HBs titers > 100 IU/L[82–84,87].

Unfortunately, even in patients without overt recurrence of HBV infection, HBV DNA may be detectable by PCR in serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cells or liver tissue in 45% of patients with high-dose IV HBIG 10 years after LT[87]. Similarly, Hussain et al[88] recently found that HBV DNA was detected in > 80% of allograft livers in patients who remained serum HBsAg-negative and HBV DNA-negative under combination high-dose IV HBIG/LAM prophylaxis. These data suggest that combination high-dose IV HBIG/LAM prophylaxis cannot eradicate HBV, which also explains the life-long need for HBIG in most patients.

Although combined high-dose IV HBIG and LAM is very effective in preventing recurrent HBV infection, the major limitation of such a regimen is its high cost, estimated at > $100 000 in the first year post-transplantation and > $50 000 yearly thereafter[89]. Other factors including inconvenient administration and unavailability of IV HBIG in some countries limit extensive acceptance of this regimen.

Low-dose IM HBIG and LAM combination therapy

In an attempt to lower the high cost of the combination regimen of high-dose IV HBIG and LAM, new strategies are under consideration. Among these strategies, combination prophylaxis with low-dose IM HBIG has been investigated most extensively, and is regarded as the most cost-effective regimen for the prevention of post-transplant HBV recurrence in recipients without pretransplant LAM resistance. Some studies[77,90–93] concerning this regimen are summarized in Table 2. Recurrence rates reported by major studies[90–93] are similar to those documented with high-dose IV HBIG, and cost reduction by > 50% has led to rapid acceptance of the IM route in many centers. However, a higher rate of recurrence with combined low-dose IM HBIG/LAM prophylaxis was reported by Zheng et al[77]. In this retrospective study, 14% developed recurrence at a mean 15.8 mo after LT. The likely explanation is that approximately one-third of patients were high-risk patients, with pretransplantation HBV DNA levels > 105 copies/mL. These patients with positive HBV DNA at LT are more likely to develop HBV reinfection after LT. Thus, the number of patients with active viral replication at LT will influence the efficacy of low-dose IM HBIG and LAM combination therapy.

Table 2.

Prevention of HBV recurrence after LT with LAM and low-dose IM HBIG

| Authors | Patients (n) | DNA+ prior to LT (%) | Pretransplant LAM therapy (%) | Duration of pretransplant LAM therapy (mean mo) | DNA+ at LT (%) | Prophylactic protocol after LT | Follow-up (mean mo) | Recurrence(%) |

| Jiao et al[90] | 79 | 47 | 28 | 0.5 | 0 | LAM + HBIG IM1 | 29 | 2.5 |

| Gane et al[91] | 147 | 85 | NA | 3 | < 50 | LAM + HBIG IM2 | 61 | 4 |

| Zheng et al[77] | 114 | NA | 13 | 5 | 31 | LAM + HBIG IM3 | 16 | 14 |

| Karademir et al[92] | 35 | 51 | 40 | 6 | 14 | LAM + HBIG IM4 | 16 | 5.7 |

| Angus et al[93] | 32 | 97 | 100 | 3.2 | NA | LAM + HBIG IM5 | 18.4 | 3.1 |

NA: Not available.

2000 IU (IM) at LT, 800 IU (IM) daily for 6 d, weekly for 3 wk, then aim for anti-HBs > 100 IU/L;

800 IU (IM) at LT and daily for 6 d, then 800 IU (IM) monthly;

2000 IU (IM) at LT, 800 IU (IM) daily for 6 d, weekly for 3 mo, and then monthly;

4000 IU (IM) at LT, 2000 IU (IM) daily until anti-HBs > 200 IU/L, then aim for > 100 IU/L;

800 IU (IM) at LT and daily for 1 wk, then 800 IU (IM) monthly.

In addition, IM HBIG has been used as long-term maintenance therapy following initial therapy with high doses of IV HBIG[94–96] (Table 3). Although conversion from IV to IM HBIG in combination with LAM can achieve the same prophylactic efficacy as direct low-dose IM HBIG and LAM combination therapy, supplemental IV HBIG is still required in some patients[95,96]. As a result of this inconvenience and the recent finding that HB surface antibody (HBsAb) trough level and half-life do not differ after post-transplantation IV and IM HBIG administration[97], most centers prefer to use low-dose IM HBIG and LAM combination therapy.

Table 3.

Conversion from IV to IM HBIG for prevention of HBV recurrence after LT

| Authors | Patients (n) | DNA+ prior to LT (%) | Pretransplant LAM therapy (%) | Duration of pretransplant LAM therapy (mean mo) | DNA+ at LT (%) | Prophylactic protocol after LT | Follow-up (mean mo) | Recurrence (%) |

| Ferretti et al[94] | 23 | 48 | 48 | NA | 13 | LAM + HBIG1 | 20 | 3.6 |

| Han et al[95] | 59 | NA | 59 | 7.7 | 8 | LAM + HBIG2 | 35 | 03, 24 |

| Faust et al[96] | 6 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | LAM + HBIG5 | 43 | 0 |

80 000 IU (IV) in the first wk, then 1200 IU (IM) to aim for anti-HBs > 100 IU/L;

IV for a median of 67 wk (LT before August 1998), then IM thereafter; 10 000 IU (IV) at LT, then 10 000 IU (IV) daily for 6 d (LT after August 1998), then IM thereafter;

The HBV recurrence of patients with LT before August 1998;

The HBV recurrence of patients with LT after August 1998;

10 000 IU (IV) at LT, then 2000 IU (IV) for a median of 7 mo, then IM thereafter.

Other post-transplant prophylactic strategies

High costs and inconvenience caused by indefinite HBIG administration have led to controversy as to whether indefinite passive immunization is necessary. In order to stop HBIG after initial monotherapy or combination prophylaxis with LAM, the first approach is to switch from HBIG or HBIG/LAM to LAM monotherapy. The early results were promising. For example, Dodson et al[98] switched 16 patients from HBIG to LAM monotherapy after 2 years and had no HBV recurrence 51 mo after LT. In another study by Buti et al[99], 29 patients who were HBV-DNA-negative at the time of LT were treated with high-dose HBIG for the first month, and then they were randomized to receive LAM monotherapy (14 patients) or LAM plus HBIG (15 patients) until month 18. None of the patients developed HBV recurrence during the study period. However, with longer follow-up, a recurrence rate of 11%-17% was observed[100,101]. Thus, it is important to determine which patients can stop HBIG. Although it has not yet been defined who can safely discontinue HBIG therapy, the best candidates are probably the following: those without virus replication at the time of transplantation; at least 2 years of HBIG treatment; and negative for HBV DNA by PCR before stopping HBIG.

The second approach is to switch from HBIG/LAM to a combination of antiviral agents. In a recent multicenter randomized prospective study, 16 of 34 patients receiving low-dose IM HBIG/LAM prophylaxis, without HBV recurrence at least 12 mo post-transplantation, were switched to ADV/LAM combination therapy and 18 continued with HBIG/LAM[102]. After a median follow-up of 21.1 mo in the ADV/LAM group and 21.8 mo in the HBIG/LAM group, no patient in either group had HBV recurrence, although one in the ADV/LAM group became HBsAg-positive at 5 mo, but HBV DNA was persistently undetectable by PCR (sensitivity 14 IU/mL). The annual cost of combination ADV/LAM prophylaxis was $8290 versus $13 718 for IM HBIG/LAM. Neff et al[103] retrospectively investigated a small cohort of non-HBV-replicating patients who were converted from HBIG/LAM to ADV/LAM therapy after a mean post-LT period of 6.5 mo. The mean length of follow-up since therapy conversion was 21 mo. They found that none of the patients showed an increase in transaminases while on dual nucleos(t)ide analog therapy. Unfortunately, there were no results given after the therapy switch, although the authors mentioned that HBV serological testing was performed. Another study[104] has also suggested that this approach may be highly effective and have significant cost savings. In addition, new drugs such as entecavir, telbivudine and tenofovir, are probably candidates to substitute for the indefinite HBIG maintenance therapy after LT. However, available studies are limited, of small size and short follow-up. Thus, larger, randomized prospective studies are required to confirm if combination of antiviral agents is sufficient as a prophylactic strategy against HBV recurrence post-transplantation.

The third approach to prevent HBV recurrence post-transplantation is utilization of active HBV vaccination. Notably, studies regarding this approach have yielded variable results. Successful active immunization in 14 out of 17 hepatitis B patients (82%) after LT was reported by Sanchez-Fueyo et al[105] in a cohort of carefully selected low-risk patients. In contrast, in another study, discontinuation of HBIG with a triple course of vaccine produced detectable HBsAb levels in only 18% of recipients[106]. In addition, new hepatitis B vaccines, or conventional vaccines in combination with new adjuvants are hoped to improve anti-HBs responses in transplant recipients. In a study reported by Bienzle et al[107], 16 out of 20 patients (80%) achieved protective antibody titers of > 500 IU/L by using an IM recombinant HBV vaccine combined with two immunostimulants under continuation of passive immunoprophylaxis. However, other studies have failed to replicate this result by using adjuvants and concomitant HBIG administration[108,109]. Therefore, further studies are needed before this approach can be recommended for widespread clinical application.

CONCLUSION

In the setting of pretransplantation, LAM has been proposed to be downgraded from first- to second-line therapy because of its resistance profile. In contrast, ADV has been approved not only as first-line therapy, but also as rescue therapy for patients with LAM resistance. Furthermore, combination of ADV and LAM may result in lower risk of ADV resistance than ADV monotherapy. Other new drugs such as entecavir, telbivudine and tenofovir, are probably candidates for the treatment of HBsAg-positive patients awaiting LT, but long-term studies are needed to evaluate the safety and resistance of these new antiviral drugs.

In the post-transplantation setting, low-dose IM HBIG, in combination with LAM, is regarded as the most cost-effective regimen for the prevention of HBV recurrence in recipients without pretransplant LAM resistance, and is rapidly being accepted in many transplant centers. With the introduction of new antiviral drugs, new hepatitis B vaccine and its new adjuvants, post-transplant HBIG-free therapeutic regimens are promising, particularly in those patients with low risk of HBV recurrence.

Peer reviewers: Josh Levitsky, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, 675 N St. Clair St. Suite 15-250, Chicago, IL 60611, United States; Raymund R Razonable, MD, Division of Infectious Diseases, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, Minnesota 55905, United States

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Seaberg EC, Belle SH, Beringer KC, Schivins JL, Detre KM. Liver transplantation in the United States from 1987-1998: updated results from the Pitt-UNOS Liver Transplant Registry. Clin Transpl. 1998:17–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Lai CL, Wong J. Prophylaxis and treatment of recurrent hepatitis B after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75:S41–S44. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000047027.68167.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Todo S, Demetris AJ, Van Thiel D, Teperman L, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Orthotopic liver transplantation for patients with hepatitis B virus-related liver disease. Hepatology. 1991;13:619–626. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinmuller T, Seehofer D, Rayes N, Muller AR, Settmacher U, Jonas S, Neuhaus R, Berg T, Hopf U, Neuhaus P. Increasing applicability of liver transplantation for patients with hepatitis B-related liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;35:1528–1535. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, Kremers WK, Ishitani MB, Dickson ER. Outcome of liver transplantation for hepatitis B in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:968–974. doi: 10.1002/lt.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoofnagle JH, Di Bisceglie AM, Waggoner JG, Park Y. Interferon alfa for patients with clinically apparent cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1116–1121. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90281-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niederau C, Heintges T, Lange S, Goldmann G, Niederau CM, Mohr L, Haussinger D. Long-term follow-up of HBeAg-positive patients treated with interferon alfa for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1422–1427. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605303342202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tchervenkov JI, Tector AJ, Barkun JS, Sherker A, Forbes CD, Elias N, Cantarovich M, Cleland P, Metrakos P, Meakins JL. Recurrence-free long-term survival after liver transplantation for hepatitis B using interferon-alpha pretransplant and hepatitis B immune globulin posttransplant. Ann Surg. 1997;226:356–365; discussion 365-368. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo CM, Liu CL, Chan SC, Lam CM, Poon RT, Ng IO, Fan ST, Wong J. A randomized, controlled trial of postoperative adjuvant interferon therapy after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;245:831–842. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000245829.00977.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan HL, Hui AY, Wong VW, Chim AM, Wong ML, Sung JJ. Long-term follow-up of peginterferon and lamivudine combination treatment in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2005;41:1357–1364. doi: 10.1002/hep.20695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buster EH, Flink HJ, Cakaloglu Y, Simon K, Trojan J, Tabak F, So TM, Feinman SV, Mach T, Akarca US, Schutten M, Tielemans W, van Vuuren AJ, Hansen BE, Janssen HL. Sustained HBeAg and HBsAg loss after long-term follow-up of HBeAg-positive patients treated with peginterferon alpha-2b. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:459–467. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flink HJ, Buster EH, Merican I, Nevens F, Kitis G, Cianciara J, de Vries RA, Hansen BE, Schalm SW, Janssen HL. Relapse after treatment with peginterferon alpha-2b alone or in combination with lamivudine in HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 2007;56:1485–1486. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.125633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruger M, Tillmann HL, Trautwein C, Bode U, Oldhafer K, Maschek H, Boker KH, Broelsch CE, Pichlmayr R, Manns MP. Famciclovir treatment of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation: a pilot study. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:253–262. doi: 10.1002/lt.500020402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manns MP, Neuhaus P, Atkinson GF, Griffin KE, Barnass S, Vollmar J, Yeang Y, Young CL. Famciclovir treatment of hepatitis B infection following liver transplantation: a long-term, multi-centre study. Transpl Infect Dis. 2001;3:16–23. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.2001.003001016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh N, Gayowski T, Wannstedt CF, Wagener MM, Marino IR. Pretransplant famciclovir as prophylaxis for hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1997;63:1415–1419. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199705270-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seehofer D, Rayes N, Naumann U, Neuhaus R, Muller AR, Tullius SG, Berg T, Steinmuller T, Bechstein WO, Neuhaus P. Preoperative antiviral treatment and postoperative prophylaxis in HBV-DNA positive patients undergoing liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;72:1381–1385. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200110270-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villeneuve JP, Condreay LD, Willems B, Pomier-Layrargues G, Fenyves D, Bilodeau M, Leduc R, Peltekian K, Wong F, Margulies M, et al. Lamivudine treatment for decompensated cirrhosis resulting from chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2000;31:207–210. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao FY, Terrault NA, Freise C, Maslow L, Bass NM. Lamivudine treatment is beneficial in patients with severely decompensated cirrhosis and actively replicating hepatitis B infection awaiting liver transplantation: a comparative study using a matched, untreated cohort. Hepatology. 2001;34:411–416. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapoor D, Guptan RC, Wakil SM, Kazim SN, Kaul R, Agarwal SR, Raisuddin S, Hasnain SE, Sarin SK. Beneficial effects of lamivudine in hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;33:308–312. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikolaidis N, Vassiliadis T, Giouleme O, Tziomalos K, Grammatikos N, Patsiaoura K, Orfanou-Koumerkeridou E, Balaska A, Eugenidis N. Effect of lamivudine treatment in patients with decompensated cirrhosis due to anti-HBe positive/HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Clin Transplant. 2005;19:321–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2005.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, Tanwandee T, Tao QM, Shue K, Keene ON, Dixon JS, Gray DF, Sabbat J. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521–1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai CL, Dienstag J, Schiff E, Leung NW, Atkins M, Hunt C, Brown N, Woessner M, Boehme R, Condreay L. Prevalence and clinical correlates of YMDD variants during lamivudine therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:687–696. doi: 10.1086/368083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lok AS, Heathcote EJ, Hoofnagle JH. Management of hepatitis B: 2000--summary of a workshop. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1828–1853. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seehofer D, Rayes N, Berg T, Neuhaus R, Muller AR, Hopf U, Bechstein WO, Neuhaus P. Lamivudine as first- and second-line treatment of hepatitis B infection after liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2000;13:290–296. doi: 10.1007/s001470050704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lok AS, Lai CL, Leung N, Yao GB, Cui ZY, Schiff ER, Dienstag JL, Heathcote EJ, Little NR, Griffiths DA, et al. Long-term safety of lamivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1714–1722. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natsuizaka M, Hige S, Ono Y, Ogawa K, Nakanishi M, Chuma M, Yoshida S, Asaka M. Long-term follow-up of chronic hepatitis B after the emergence of mutations in the hepatitis B virus polymerase region. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:154–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fontana RJ, Keeffe EB, Carey W, Fried M, Reddy R, Kowdley KV, Soldevila-Pico C, McClure LA, Lok AS. Effect of lamivudine treatment on survival of 309 North American patients awaiting liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:433–439. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.32983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zoulim F, Radenne S, Ducerf C. Management of patients with decompensated hepatitis B virus associated [corrected] cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2008;14 Suppl 2:S1–S7. doi: 10.1002/lt.21615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang TT, Kitis G, Rizzetto M, Marcellin P, Lim SG, Goodman Z, Ma J, et al. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B for up to 5 years. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1743–1751. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang TT, Kitis G, Rizzetto M, Marcellin P, Lim SG, Goodman Z, Ma J, et al. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2673–2681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcellin P, Chang TT, Lim SG, Tong MJ, Sievert W, Shiffman ML, Jeffers L, Goodman Z, Wulfsohn MS, Xiong S, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:808–816. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng M, Mao Y, Yao G, Wang H, Hou J, Wang Y, Ji BN, Chang CN, Barker KF. A double-blind randomized trial of adefovir dipivoxil in Chinese subjects with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2006;44:108–116. doi: 10.1002/hep.21225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcellin P, Chang TT, Lim SG, Sievert W, Tong M, Arterburn S, Borroto-Esoda K, Frederick D, Rousseau F. Long-term efficacy and safety of adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2008;48:750–758. doi: 10.1002/hep.22414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiff ER, Lai CL, Hadziyannis S, Neuhaus P, Terrault N, Colombo M, Tillmann HL, Samuel D, Zeuzem S, Lilly L, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil therapy for lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B in pre- and post-liver transplantation patients. Hepatology. 2003;38:1419–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schiff E, Lai CL, Hadziyannis S, Neuhaus P, Terrault N, Colombo M, Tillmann H, Samuel D, Zeuzem S, Villeneuve JP, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for wait-listed and post-liver transplantation patients with lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B: final long-term results. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:349–360. doi: 10.1002/lt.20981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rapti I, Dimou E, Mitsoula P, Hadziyannis SJ. Adding-on versus switching-to adefovir therapy in lamivudine-resistant HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:307–313. doi: 10.1002/hep.21534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manolakopoulos S, Bethanis S, Koutsounas S, Goulis J, Vlachogiannakos J, Christias E, Saveriadis A, Pavlidis C, Triantos C, Christidou A, et al. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil in hepatitis B e antigen-negative patients developing resistance to lamivudine. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:266–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fung J, Lai CL, Yuen JC, Wong DK, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Yuen MF. Adefovir dipivoxil monotherapy and combination therapy with lamivudine for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B in an Asian population. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pellicelli AM, Barbaro G, Francavilla R, Romano M, Barbarini G, Mazzoni E, Mecenate F, Paffetti A, Barlattani A, Struglia C, et al. Adefovir and lamivudine in combination compared with adefovir monotherapy in HBeAg-negative adults with chronic hepatitis B virus infection and clinical or virologic resistance to lamivudine: A retrospective, multicenter, nonrandomized, open-label study. Clin Ther. 2008;30:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters MG, Hann Hw H, Martin P, Heathcote EJ, Buggisch P, Rubin R, Bourliere M, Kowdley K, Trepo C, Gray Df D, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil alone or in combination with lamivudine in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:91–101. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nam SW, Bae SH, Lee SW, Kim YS, Kang SB, Choi JY, Cho SH, Yoon SK, Han JY, Yang JM, et al. Short-term overlap lamivudine treatment with adefovir dipivoxil in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1781–1784. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fung SK, Chae HB, Fontana RJ, Conjeevaram H, Marrero J, Oberhelman K, Hussain M, Lok AS. Virologic response and resistance to adefovir in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2006;44:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, Chao YC, Lok AS, Han KH, Goodman Z, Zhu J, et al. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1001–1010. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai CL, Shouval D, Lok AS, Chang TT, Cheinquer H, Goodman Z, DeHertogh D, Wilber R, Zink RC, Cross A, et al. Entecavir versus lamivudine for patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1011–1020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schiff E, Simsek H, Lee WM, Chao YC, Sette H Jr, Janssen HL, Han SH, Goodman Z, Yang J, Brett-Smith H, et al. Efficacy and safety of entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2776–2783. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gish RG, Lok AS, Chang TT, de Man RA, Gadano A, Sollano J, Han KH, Chao YC, Lee SD, Harris M, et al. Entecavir therapy for up to 96 weeks in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1437–1444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leung N, Peng CY, Hann HW, Sollano J, Lao-Tan J, Hsu CW, Lesmana L, Yuen MF, Jeffers L, Sherman M, et al. Early hepatitis B virus DNA reduction in hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients with chronic hepatitis B: A randomized international study of entecavir versus adefovir. Hepatology. 2009;49:72–79. doi: 10.1002/hep.22658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baldick CJ, Tenney DJ, Mazzucco CE, Eggers BJ, Rose RE, Pokornowski KA, Yu CF, Colonno RJ. Comprehensive evaluation of hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase substitutions associated with entecavir resistance. Hepatology. 2008;47:1473–1482. doi: 10.1002/hep.22211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colonno RJ, Rose R, Baldick CJ, Levine S, Pokornowski K, Yu CF, Walsh A, Fang J, Hsu M, Mazzucco C, et al. Entecavir resistance is rare in nucleoside naive patients with hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2006;44:1656–1665. doi: 10.1002/hep.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sherman M, Yurdaydin C, Sollano J, Silva M, Liaw YF, Cianciara J, Boron-Kaczmarska A, Martin P, Goodman Z, Colonno R, et al. Entecavir for treatment of lamivudine-refractory, HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2039–2049. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villet S, Ollivet A, Pichoud C, Barraud L, Villeneuve JP, Trepo C, Zoulim F. Stepwise process for the development of entecavir resistance in a chronic hepatitis B virus infected patient. J Hepatol. 2007;46:531–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hou J, Yin YK, Xu D, Tan D, Niu J, Zhou X, Wang Y, Zhu L, He Y, Ren H, et al. Telbivudine versus lamivudine in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B: Results at 1 year of a randomized, double-blind trial. Hepatology. 2008;47:447–454. doi: 10.1002/hep.22075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lai CL, Leung N, Teo EK, Tong M, Wong F, Hann HW, Han S, Poynard T, Myers M, Chao G, et al. A 1-year trial of telbivudine, lamivudine, and the combination in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:528–536. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lai CL, Gane E, Liaw YF, Hsu CW, Thongsawat S, Wang Y, Chen Y, Heathcote EJ, Rasenack J, Bzowej N, et al. Telbivudine versus lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2576–2588. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, Gane E, de Man RA, Krastev Z, Germanidis G, Lee SS, Flisiak R, Kaita K, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2442–2455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Bommel F, Zollner B, Sarrazin C, Spengler U, Huppe D, Moller B, Feucht HH, Wiedenmann B, Berg T. Tenofovir for patients with lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and high HBV DNA level during adefovir therapy. Hepatology. 2006;44:318–325. doi: 10.1002/hep.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lauchart W, Muller R, Pichlmayr R. Long-term immunoprophylaxis of hepatitis B virus reinfection in recipients of human liver allografts. Transplant Proc. 1987;19:4051–4053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samuel D, Muller R, Alexander G, Fassati L, Ducot B, Benhamou JP, Bismuth H. Liver transplantation in European patients with the hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1842–1847. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312163292503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galun E, Eren R, Safadi R, Ashour Y, Terrault N, Keeffe EB, Matot E, Mizrachi S, Terkieltaub D, Zohar M, et al. Clinical evaluation (phase I) of a combination of two human monoclonal antibodies to HBV: safety and antiviral properties. Hepatology. 2002;35:673–679. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shouval D, Samuel D. Hepatitis B immune globulin to prevent hepatitis B virus graft reinfection following liver transplantation: a concise review. Hepatology. 2000;32:1189–1195. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.19789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sawyer RG, McGory RW, Gaffey MJ, McCullough CC, Shephard BL, Houlgrave CW, Ryan TS, Kuhns M, McNamara A, Caldwell SH, et al. Improved clinical outcomes with liver transplantation for hepatitis B-induced chronic liver failure using passive immunization. Ann Surg. 1998;227:841–850. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199806000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Terrault NA, Zhou S, Combs C, Hahn JA, Lake JR, Roberts JP, Ascher NL, Wright TL. Prophylaxis in liver transplant recipients using a fixed dosing schedule of hepatitis B immunoglobulin. Hepatology. 1996;24:1327–1333. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McGory RW, Ishitani MB, Oliveira WM, Stevenson WC, McCullough CS, Dickson RC, Caldwell SH, Pruett TL. Improved outcome of orthotopic liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B cirrhosis with aggressive passive immunization. Transplantation. 1996;61:1358–1364. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199605150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lok AS. Prevention of recurrent hepatitis B post-liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:S67–S73. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.35780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Protzer-Knolle U, Naumann U, Bartenschlager R, Berg T, Hopf U, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, Neuhaus P, Gerken G. Hepatitis B virus with antigenically altered hepatitis B surface antigen is selected by high-dose hepatitis B immune globulin after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1998;27:254–263. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trautwein C, Schrem H, Tillmann HL, Kubicka S, Walker D, Boker KH, Maschek HJ, Pichlmayr R, Manns MP. Hepatitis B virus mutations in the pre-S genome before and after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1996;24:482–488. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ghany MG, Ayola B, Villamil FG, Gish RG, Rojter S, Vierling JM, Lok AS. Hepatitis B virus S mutants in liver transplant recipients who were reinfected despite hepatitis B immune globulin prophylaxis. Hepatology. 1998;27:213–222. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hwang S, Lee SG, Ahn CS, Kim KH, Moon DB, Ha TY, Song GW, Jung DH, Park JI, Ryu JH, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B recurrence after living donor liver transplantation: primary high-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin monotherapy and rescue antiviral therapy. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:770–778. doi: 10.1002/lt.21440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee KW, Lee DS, Lee HH, Kim SJ, Joh JW, Seo JM, Choe YH, Lee SK. Prevention of de novo hepatitis B infection from HbcAb-positive donors in living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:2311–2312. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.08.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takemura N, Sugawara Y, Tamura S, Makuuchi M. Liver transplantation using hepatitis B core antibody-positive grafts: review and university of Tokyo experience. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2472–2477. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grellier L, Mutimer D, Ahmed M, Brown D, Burroughs AK, Rolles K, McMaster P, Beranek P, Kennedy F, Kibbler H, et al. Lamivudine prophylaxis against reinfection in liver transplantation for hepatitis B cirrhosis. Lancet. 1996;348:1212–1215. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)04444-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lo CM, Cheung ST, Lai CL, Liu CL, Ng IO, Yuen MF, Fan ST, Wong J. Liver transplantation in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B using lamivudine prophylaxis. Ann Surg. 2001;233:276–281. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200102000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perrillo RP, Wright T, Rakela J, Levy G, Schiff E, Gish R, Martin P, Dienstag J, Adams P, Dickson R, et al. A multicenter United States-Canadian trial to assess lamivudine monotherapy before and after liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2001;33:424–432. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mutimer D, Dusheiko G, Barrett C, Grellier L, Ahmed M, Anschuetz G, Burroughs A, Hubscher S, Dhillon AP, Rolles K, et al. Lamivudine without HBIg for prevention of graft reinfection by hepatitis B: long-term follow-up. Transplantation. 2000;70:809–815. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200009150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Limquiaco JL, Wong J, Wong VW, Wong GL, Tse CH, Chan HY, Kwan KY, Lai PB, Chan HL. Lamivudine monoprophylaxis and adefovir salvage for liver transplantation in chronic hepatitis B: a seven-year follow-up study. J Med Virol. 2009;81:224–229. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jiao ZY, Jiao Z. Prophylaxis of recurrent hepatitis B in Chinese patients after liver transplantation using lamivudine combined with hepatitis B immune globulin according to the titer of antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:1533–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zheng S, Chen Y, Liang T, Lu A, Wang W, Shen Y, Zhang M. Prevention of hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation using lamivudine or lamivudine combined with hepatitis B Immunoglobulin prophylaxis. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:253–258. doi: 10.1002/lt.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen YS, Wang CC, de Villa VH, Wang SH, Cheng YF, Huang TL, Jawan B, Chiu KW, Chen CL. Prevention of de novo hepatitis B virus infection in living donor liver transplantation using hepatitis B core antibody positive donors. Clin Transplant. 2002;16:405–409. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2002.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yu AS, Vierling JM, Colquhoun SD, Arnaout WS, Chan CK, Khanafshar E, Geller SA, Nichols WS, Fong TL. Transmission of hepatitis B infection from hepatitis B core antibody--positive liver allografts is prevented by lamivudine therapy. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:513–517. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.23911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Avolio AW, Nure E, Pompili M, Barbarino R, Basso M, Caccamo L, Magalini S, Agnes S, Castagneto M. Liver transplantation for hepatitis B virus patients: long-term results of three therapeutic approaches. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1961–1964. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Loomba R, Rowley AK, Wesley R, Smith KG, Liang TJ, Pucino F, Csako G. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin and Lamivudine improve hepatitis B-related outcomes after liver transplantation: meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:696–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marzano A, Salizzoni M, Debernardi-Venon W, Smedile A, Franchello A, Ciancio A, Gentilcore E, Piantino P, Barbui AM, David E, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation in cirrhotic patients treated with lamivudine and passive immunoprophylaxis. J Hepatol. 2001;34:903–910. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Markowitz JS, Martin P, Conrad AJ, Markmann JF, Seu P, Yersiz H, Goss JA, Schmidt P, Pakrasi A, Artinian L, et al. Prophylaxis against hepatitis B recurrence following liver transplantation using combination lamivudine and hepatitis B immune globulin. Hepatology. 1998;28:585–589. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Han SH, Ofman J, Holt C, King K, Kunder G, Chen P, Dawson S, Goldstein L, Yersiz H, Farmer DG, et al. An efficacy and cost-effectiveness analysis of combination hepatitis B immune globulin and lamivudine to prevent recurrent hepatitis B after orthotopic liver transplantation compared with hepatitis B immune globulin monotherapy. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:741–748. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2000.18702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Steinmuller T, Seehofer D, Rayes N, Muller AR, Settmacher U, Jonas S, Neuhaus R, Berg T, Hopf U, Neuhaus P. Increasing applicability of liver transplantation for patients with hepatitis B-related liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;35:1528–1535. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rosenau J, Tillmann HL, Bahr MJ, Trautwein C, Boeker KH, Nashan B, Klempnauer J, Manns MP. Successful hepatitis B reinfection prophylaxis with lamivudine and hepatitis B immune globulin in patients with positive HBV-DNA at time of liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:3637–3638. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02564-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roche B, Feray C, Gigou M, Roque-Afonso AM, Arulnaden JL, Delvart V, Dussaix E, Guettier C, Bismuth H, Samuel D. HBV DNA persistence 10 years after liver transplantation despite successful anti-HBS passive immunoprophylaxis. Hepatology. 2003;38:86–95. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hussain M, Soldevila-Pico C, Emre S, Luketic V, Lok AS. Presence of intrahepatic (total and ccc) HBV DNA is not predictive of HBV recurrence after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1137–1144. doi: 10.1002/lt.21179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dan YY, Wai CT, Yeoh KG, Lim SG. Prophylactic strategies for hepatitis B patients undergoing liver transplant: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:736–746. doi: 10.1002/lt.20685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jiao ZY, Yan LN, Li B, Zeng Y, Wen TF, Lu SC, Zhao JC, Wang WT, Xu MQ, Yang JY, et al. [Liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B patients with lamivudine monotherapy or lamivudine combined with individualized low-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin treatment] Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2007;15:804–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gane EJ, Angus PW, Strasser S, Crawford DH, Ring J, Jeffrey GP, McCaughan GW. Lamivudine plus low-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin to prevent recurrent hepatitis B following liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:931–937. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Karademir S, Astarcioglu H, Akarsu M, Ozkardesler S, Ozzeybek D, Sayiner A, Akan M, Tankurt E, Astarcioglu I. Prophylactic use of low-dose, on-demand, intramuscular hepatitis B immunoglobulin and lamivudine after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:579–583. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Angus PW, McCaughan GW, Gane EJ, Crawford DH, Harley H. Combination low-dose hepatitis B immune globulin and lamivudine therapy provides effective prophylaxis against posttransplantation hepatitis B. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:429–433. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2000.8310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ferretti G, Merli M, Ginanni Corradini S, Callejon V, Tanzilli P, Masini A, Ferretti S, Iappelli M, Rossi M, Rivanera D, et al. Low-dose intramuscular hepatitis B immune globulin and lamivudine for long-term prophylaxis of hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:535–538. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Han SH, Martin P, Edelstein M, Hu R, Kunder G, Holt C, Saab S, Durazo F, Goldstein L, Farmer D, et al. Conversion from intravenous to intramuscular hepatitis B immune globulin in combination with lamivudine is safe and cost-effective in patients receiving long-term prophylaxis to prevent hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:182–187. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Faust D, Rabenau HF, Allwinn R, Caspary WF, Zeuzem S. Cost-effective and safe ambulatory long-term immunoprophylaxis with intramuscular instead of intravenous hepatitis B immunoglobulin to prevent reinfection after orthotopic liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2003;17:254–258. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2003.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hooman N, Rifai K, Hadem J, Vaske B, Philipp G, Priess A, Klempnauer J, Tillmann HL, Manns MP, Rosenau J. Antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen trough levels and half-lives do not differ after intravenous and intramuscular hepatitis B immunoglobulin administration after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:435–442. doi: 10.1002/lt.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dodson SF, de Vera ME, Bonham CA, Geller DA, Rakela J, Fung JJ. Lamivudine after hepatitis B immune globulin is effective in preventing hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:434–439. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2000.6446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Buti M, Mas A, Prieto M, Casafont F, Gonzalez A, Miras M, Herrero JI, Jardi R, Cruz de Castro E, Garcia-Rey C. A randomized study comparing lamivudine monotherapy after a short course of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIg) and lamivudine with long-term lamivudine plus HBIg in the prevention of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2003;38:811–817. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Naoumov NV, Lopes AR, Burra P, Caccamo L, Iemmolo RM, de Man RA, Bassendine M, O’Grady JG, Portmann BC, Anschuetz G, et al. Randomized trial of lamivudine versus hepatitis B immunoglobulin for long-term prophylaxis of hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2001;34:888–894. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Buti M, Mas A, Prieto M, Casafont F, Gonzalez A, Miras M, Herrero JI, Jardi R, Esteban R. Adherence to Lamivudine after an early withdrawal of hepatitis B immune globulin plays an important role in the long-term prevention of hepatitis B virus recurrence. Transplantation. 2007;84:650–654. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000277289.23677.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Angus PW, Patterson SJ, Strasser SI, McCaughan GW, Gane E. A randomized study of adefovir dipivoxil in place of HBIG in combination with lamivudine as post-liver transplantation hepatitis B prophylaxis. Hepatology. 2008;48:1460–1466. doi: 10.1002/hep.22524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Neff GW, Kemmer N, Kaiser TE, Zacharias VC, Alonzo M, Thomas M, Buell J. Combination therapy in liver transplant recipients with hepatitis B virus without hepatitis B immune globulin. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2497–2500. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nath DS, Kalis A, Nelson S, Payne WD, Lake JR, Humar A. Hepatitis B prophylaxis post-liver transplant without maintenance hepatitis B immunoglobulin therapy. Clin Transplant. 2006;20:206–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2005.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sanchez-Fueyo A, Rimola A, Grande L, Costa J, Mas A, Navasa M, Cirera I, Sanchez-Tapias JM, Rodes J. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin discontinuation followed by hepatitis B virus vaccination: A new strategy in the prophylaxis of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2000;31:496–501. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Angelico M, Di Paolo D, Trinito MO, Petrolati A, Araco A, Zazza S, Lionetti R, Casciani CU, Tisone G. Failure of a reinforced triple course of hepatitis B vaccination in patients transplanted for HBV-related cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2002;35:176–181. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bienzle U, Gunther M, Neuhaus R, Vandepapeliere P, Vollmar J, Lun A, Neuhaus P. Immunization with an adjuvant hepatitis B vaccine after liver transplantation for hepatitis B-related disease. Hepatology. 2003;38:811–819. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rosenau J, Hooman N, Rifai K, Solga T, Tillmann HL, Grzegowski E, Nashan B, Klempnauer J, Strassburg CP, Wedemeyer H, et al. Hepatitis B virus immunization with an adjuvant containing vaccine after liver transplantation for hepatitis B-related disease: failure of humoral and cellular immune response. Transpl Int. 2006;19:828–833. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rosenau J, Hooman N, Hadem J, Rifai K, Bahr MJ, Philipp G, Tillmann HL, Klempnauer J, Strassburg CP, Manns MP. Failure of hepatitis B vaccination with conventional HBsAg vaccine in patients with continuous HBIG prophylaxis after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:367–373. doi: 10.1002/lt.21003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]