Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) with hypertrophy of the basal septum is the most common etiology of left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction.

In this article, we report the case of a patient with a structurally normal heart who developed hemodynamic deterioration due to severe LVOT obstruction following treatment with catecholamines. Hypovolemia accompanied with a hyperdynamic condition, resulting from catecholamine treatment, may cause dynamic LVOT obstruction due to the systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve leaflet. The solution for this is early recognition and correction of aggravating factors such as, withdrawal of catecholamine therapy and volume replacement.

Keywords: Left ventricular outflow obstruction, Catecholamines

INTRODUCTION

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common cause of dynamic left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction. The hypertrophy of the basal septum and systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve leaflet (SAM) cause a dynamic obstruction in the LVOT1-3). The dynamic LVOT obstruction may occur as a result of other conditions such as, aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis, hypertensive hypertrophy, dehydration, sepsis, vasodilatation, acute myocardial infarction, and mitral valve repair; however, it has also been observed in patients with structurally normal hearts who have been treated with catecholamine4, 5).

In this article, we report the case of a patient who developed SAM, and severe dynamic LVOT obstruction, compromised by haemodynamic deterioration as a result of catecholamine treatment, even without basal septal hypertrophy.

CASE REPORT

A 62-year-old man with a history of hypertension was admitted to a medical center due to stage IIIA non-small cell lung cancer. The cardiopulmonary physical examination, which included a routine transthoracic echocardiographic evaluation and a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), did not reveal any signs of heart abnormalities. Following neoadjuvant concurrent chemoradiation treatment, the patient underwent left lower lobectomy and mediastinal lymphadencetomy.

Three days after the operation, the patient developed adult respiratory distress syndrome with shock and was treated with mechanical ventilation, intravenous antibiotics, volume substitution, and dopamine. After another three days, a physical examination revealed bilateral crackle in the basal lung and a chest x-ray which revealed pulmonary edema (Figure 1). These symptoms improved following the intravenous infusion of the furosemide and dobutamine.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray showed diffuse reticulonodular opacities in both lungs and pulmonary edema.

Over the course of the next three weeks of treatment, the patient experienced fever (up to 39℃) and recurrent hypotensive events, which were treated with appropriate antibiotics and catecholamines. The patient's vital signs included, blood pressure of 100/80 mm Hg, heart rate of 130 beats/min, and central venous pressure of 4 to 5 cm Hg. On a follow-up physical examination, a grade 3/6 systolic murmur was detected at the left sternal border.

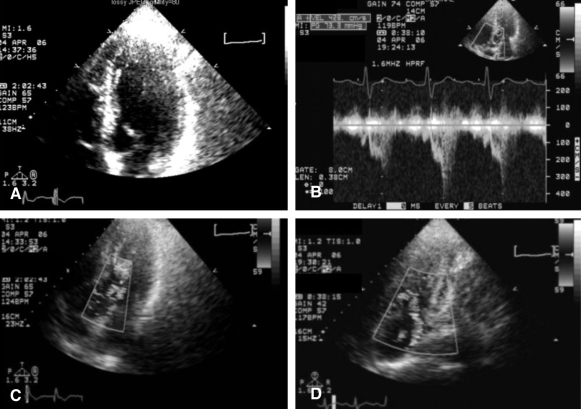

The transthoracic echocardiogram revealed the SAM with LVOT obstruction (Figure 2A). The peak pressure gradient recorded with continuous-wave Doppler in LVOT was 73.3 mm Hg (Figure 2B). In addition, a color Doppler image detected flow acceleration in the LVOT and moderate amounts of mitral regurgitation (Figure 2C, 2D).

Figure 2.

Transthoracic echocardiogram. (A) Systolic anterior motion of the mitral leaflets with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction was shown. (B) The peak pressure gradient measured with continuous Doppler in LVOT was 73.3 mm Hg. (C) Transthoracic echocardiography with color Doppler imaging showed flow acceleration in LVOT. (D) Moderate amount of mitral regurgitation was revealed on color Doppler examination.

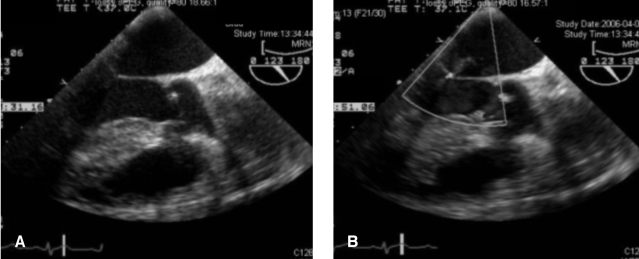

Following the parenteral substitution of crystalloid and colloid for volume replacement as well as phasing out the catecholamine treatment, the patient's condition improved dramatically. We found the patient's cardiac murmur to have disappeared, the fever subsided, and the hemodynamic condition stabilized. Upon a follow-up evaluation, a transesophageal echocardiogram revealed complete resolution of the SAM, LVOT obstruction, and mitral regurgitation (Figure 3). The patient's mechanical ventilator was successfully removed and subsequently transferred to the general ward without any further or residual complications.

Figure 3.

Transesophageal echocardiography was done to evaluate heart function after the treatment, i.e., volume replacement and stop of catecholamine infusion and to rule out acute derangement from infective endocarditis. (A) There was no more systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve. (B) The amount of mitral regurgitation reduced to trivial degree.

DISCUSSION

It is well known that hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most frequently reported cause of the dynamic LVOT obstruction1-3). As well, a hyperdynamic state as a result of catecholamine therapy6, 7) has been linked to this condition.

Dynamic LVOT obstruction has been reported in hypertensive patients during dobutamine stress echocardiography, but most of these cases did not show any significant clinical or hemodynamic changes8-10). A few cases similar to our case study have described a catecholamine-induced dynamic LVOT obstruction compromised by hemodynamic deterioration in a structurally normal heart5, 11).

Treatment with inotropic agents in patients experiencing shock symptoms remains a common practice and mandatory mainstay in the field of medicine. However, we observed that management of this condition with catecholamine may result in paradoxical hemodynamic deterioration. The mechanisms behind the catecholamine-induced deterioration may include, ischemic left ventricular dysfunction, the vasodilatation effect of dobutamine, tachycardia and the dynamic LVOT obstruction resulting from a hypercontractile state in relative hypovolemia9, 12, 13).

In our case study, hypovolemia in combination with a hyperdynamic state, induced by catecholamine administration was the key mechanism for severe dynamic LVOT obstruction with haemodynamic deterioration. Cessation of catecholamine therapy and volume replacement completely reversed the dynamic LVOT obstruction, SAM, and mitral insufficiency.

We determined that for our case study, hemodynamic deterioration leading to dynamic LVOT obstruction should be considered as an adverse effect of catecholamine treatment under the hypovolemia. A newly detected systolic murmur in the left lower sternal border may be noticed upon physical examination; however a definitive diagnosis would require an echocardiographic examination. Early detection and correction of the factors leading to deterioration of the heart, which include cessation of catecholamine therapy and intravascular volume replacement, would reverse the symptoms.

References

- 1.Maron BJ, Bonow RO, Cannon RO, 3rd, Leon MB, Epstein SE. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: interrelations of clinical manifestations, pathophysiology, and therapy (2) N Engl J Med. 1987;316:844–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704023161405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heo J, Jeong JW, Park YK, Park OK. Relationship between systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve and the left ventricular outflow pressure gradient in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Korean Circ J. 1990;20:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim KS, Jung HY, Jo JH, Kim MS, Song JS, Bae JJ. A clinical study of hypertrophic obstructive cariomyopathy: analysis by echocardiography and Doppler echocardiography. Korean Circ J. 1988;18:647–656. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallet B, Quintard H, Fruchaud J, Hiltgen M. Dynamic left ventricular obstruction associated with a pheochromocytoma reversible after tumor ablation. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2001;94:1195–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auer J, Berent R, Weber T, Lamm G, Eber B. Catecholamine therapy inducing dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Int J Cardiol. 2005;101:325–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim DY, Cho HK, Chung IM, Park SH, Park SH, Shin GJ, Chang BC. A case of left ventricular outflow obstruction caused by mitral valve replacement. Korean Circ J. 1998;28:113–117. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta R, Sewani A, Ahmad M. Dynamic systolic left ventricular gradients: differential diagnosis and management. Echocardiography. 2006;23:168–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2006.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luria D, Klutstein MW, Rosenmann D, Shaheen J, Sergey S, Tzivoni D. Prevalence and significance of left ventricular outflow gradient during dobutamine echocardiography. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:386–392. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ueda T, Mizushige K, Yukiiri K, Watanabe K, Kohno M. Hypotension and functional left ventricular obstruction during dobutamine stress echocardiography : two case reports. Angiology. 2001;52:489–492. doi: 10.1177/000331970105200708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yalcin F, Muderrisoglu H, Korkmaz ME, Ozin B, Baltali M, Yigit F. The effect of dobutamine stress on left ventricular outflow tract gradients in hypertensive patients with basal septal hypertrophy. Angiology. 2004;55:295–301. doi: 10.1177/000331970405500309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mingo S, Benedicto A, Jimenez MC, Perez MA, Montero M. Dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction secondary to catecholamine excess in a normal ventricle. Int J Cardiol. 2006;112:393–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roldan FJ, Vargas-Barron J, Espinola-Zavaleta N, Keirns C, Romero-Cardenas A. Severe dynamic obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract induced by dobutamine. Echocardiography. 2000;17:37–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2000.tb00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaul S, Stratienko AA, Pollock SG, Marieb MA, Keller MW, Sabia PJ. Value of two-dimensional echocardiography for determining the basis of hemodynamic compromise in critically ill patients: a prospective study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1994;7:598–606. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(14)80082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]