Abstract

We previously reported Clostridium difficile in 20% of retail meat in Canada, which raised concerns about potential foodborne transmissibility. Here, we studied the genetic diversity of C. difficile in retail meats, using a broad Canadian sampling infrastructure and 3 culture methods. We found 6.1% prevalence and indications of possible seasonality (highest prevalence in winter).

Keywords: Enteric infections, bacteria, Clostridium difficile, foodborne, ribotypes, seasonality, hypervirulent, meat, Canada, dispatch

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) has been associated with increased illness and death in Canada since 2000 (1,2). Although multiple genotypes with higher levels of virulence and antimicrobial resistance have been recognized (1,3), little is known about risk factors for CDI acquisition outside healthcare facilities.

In a 2005 study, we found C. difficile in 20% of retail meats sampled in Canada (4). Limitations to that study included limited geographic representation, nonsystematic sampling, and the use of a nonvalidated culture method. These sampling limitations prevent valid extrapolations. Broader sampling and a better understanding of the culture methods were thus required to reassess the prevalence of retail meat contamination with C. difficile. Here, we determined the prevalence of C. difficile in retail meat by using a broad-based government sampling infrastructure, compared 3 culture methods, characterized recovered isolates, and evaluated month-to-month variability in C. difficile recovery.

The Study

Retail meats were obtained from 2 randomly selected census divisions per week from various retailers across Canada as part of the active retail surveillance component of the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS) (5). We tested random packages of ground beef as well as veal chops from milk-fed calves; the packages were purchased by CIPARS in Ontario, Québec, and Saskatchewan, Canada, from January through August 2006. Purchased packages were sent to the Laboratory of Foodborne Zoonoses, Québec (ground beef), and to the Canadian Research Institute for Food Safety, Ontario (veal chops), where 35-g composite samples were made. Rinsates were prepared by mixing 25 g of meat and 225 mL of buffered peptone water (placed in a stomacher for 15 min). Rinsates (12 mL) and the remains of the composite samples (10 g) were then sent to the University of Guelph for C. difficile testing. Sample size estimations indicated that 211 packages were adequate to verify a prevalence of 20% ± 8% (α = 0.05, power = 0.8; Stata sampsi command [Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA]).

A total of 214 meat samples were cultured by using 3 methods. One method, used in an earlier study (4), was tested in duplicate to assess reproducibility. All protocols had an enrichment phase of 7 days (Table 1), followed by ethanol treatment of culture sediments (96%, 1:2 [vol/vol], 30 min), and inoculation onto solid agar for colony identification (4,6).

Table 1. Proportion of retail meat packages yielding Clostridium difficile in 4 culture replicates and estimated method sensitivity, Canada, 2006*†.

| Sample | Culture method |

% Samples with C. difficile |

Culture sensitivity, %‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment | Agar | Ground beef | Veal from milk-fed calves | Both‡ | |||

| Rinsate | TCDMNB | CDMNA | 2.7 (4/149)§ | 0 (0/65) | 1.9 (4/214) | 31 | |

| Meat¶ | TCDMNB | CDMNA | 2.7 (4/149)§ | 1.5 (1/65) | 2.3 (5/214) | 39 | |

| Meat¶ | TCDMNB | CDMNA | 1.3 (2/149)§ | 1.5 (1/65) | 1.4 (3/214) | 23 | |

| Meat |

TCCFB |

Blood |

|

1.3% (2/149) |

1.5 (1/65) |

1.4 (3/214) |

23 |

| Total of contaminated packages# | 6.7 (10/149) | 4.6 (3/65) | 6.1 (13/214)‡ | 100 | |||

*Rinsate, sediment; TCDMNB, in-house C. difficile broth (CM0601; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) supplemented with cysteine hydrochloride, moxalactam, norfloxacin (CDMN, SR0173E; Oxoid), and 0.1% sodium taurocholate (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) (4); Meat, 2 g; CDMNA, C. difficile agar supplemented with CDMN and 7% laked horse blood (SR0048C; Oxoid); TCCFB, broth supplemented with D-cycloserine and cefoxitin (SR0096E; Oxoid) and 0.1% sodium taurocholate; Blood, 5% defibrinated sheep blood. †Poor test agreement was found among and between cultures (κ –0.28; p>0.9). ‡Culture sensitivity calculation based on parallel interpretation of all 4 cultures (standard comparator) and 6.1% of overall contamination. Duplicate testing sensitivity ranged from 46.2% (6/13) to 61.5% (8/13). §Represents 2 packages that simultaneously tested positive in 2 culture replicates. ¶Protocol previously used to test meat; duplicate run (4). #No statistical differences were found between ground beef and veal in any culture replicate (p>0.1).

Suspected colonies (swarming, nonhemolytic) were subcultured onto 5% sheep blood agar. C. difficile was preliminarily identified with L-proline aminopeptidase activity (Pro Disc; Remel, Lenexa, KS, USA) but confirmed by PCR detection of the triose phosphate isomerase gene (7).

PCR ribotyping and detection of genes for toxins A (tcdA), B (tcdB), binary toxin (cdtB), and toxin regulator (tcdC) were performed as previously described (4,8,9). Isolates having either tcdA, tcdB, or cdtB were classified as toxigenic (10).

Resulting PCR ribotypes were visually compared to representative PCR ribotypes previously identified in cattle (n = 8, 2004), retail meats (n = 4, 2005), and humans (n = 39, 2004–2006) in Ontario and Québec, Canada (2,4,11). The first meat-derived isolate of each PCR ribotype and 1 matching human isolate were submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, for SmaI pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and toxinotyping (1).

We tested selected isolates to determine the MICs of clindamycin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and gatifloxacin by using the Etest (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) and interpreted the results after the isolates were incubated for 48 h on Brucella agar (12). Controls included C. difficile strain ATCC 700057.

Culture binary data were analyzed by using a randomized block design approach with a conditional logistic regression analysis (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and p value estimations with Monte Carlo simulations. Exact tests for pairwise comparisons were based on LogXact 7 and a Fortran program (Cytel Inc, Cambridge, MA, USA). Kappa, χ2, and Fisher exact tests were also used. Significance was held at p<0.05.

In total, 149 ground beef and 65 veal chop samples, obtained from 210 retailers in Canada, were cultured for C. difficile (Figure 1). The numbers of samples tested per month were 12, 49, 34, 5, 73, 31, 0, and 7, from January through August in 2006; 3 samples lacked sampling dates.

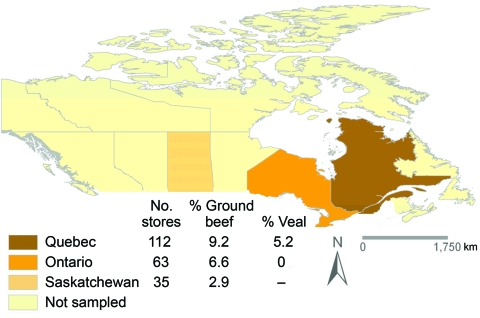

Figure 1.

Distribution of retail grocery stores sampled (n = 210) and proportion with contaminated meat. The overall proportion of stores with >1 meat package contaminated with Clostridium difficile was 5.7%. No statistical differences were observed when comparing the proportions of ground beef contamination in Québec, Ontario, and Saskatchewan, Canada (p>0.2). No comparisons for veal chops were made because Québec was the main source of this commodity; veal from milk-fed calves was not available in Saskatchewan, and only 3 stores had this type of veal during sampling in Ontario.

Combining the results from 4 cultures, we found the prevalence of C. difficile was 6.7% (10/149) in ground beef and 4.6% (3/65) in veal chops from milk-fed calves. The combined prevalence was 6.1% (13/214). The prevalence of C. difficile recovery determined by using different culture methods varied from 1.4% to 2.3%, but no culture agreement or reproducibility was observed (p>0.1). Overall, the individual diagnostic sensitivity of each method was low (<39%; Table 1).

When month-to-month variability was considered, C. difficile was more commonly isolated from meat in January and February (11.5%, 7/61) than during the remaining 5 months of the study (4%; 6/150; p = 0.041). This finding indicates possible seasonality, although further studies are needed.

A total of 28 C. difficile isolates were cultured from 13 meat packages (22 from ground beef; 6 from veal). PCR ribotyping showed 8 distinct genotypes, 7 of which were toxigenic and present in 10 (77%) meat packages (Table 2). Genotypes resembling human PCR ribotype 027/NAP1 were found in 30.8% (n = 4) of positive samples, and PCR ribotypes 077/NAP2 and 014/NAP4, formerly reported in cattle and retail meats (3,4), were identified in 23.1% (n = 3) and 15.4% (n = 2) of samples, respectively. Multiple genotype contamination was also documented (2 PCR ribotypes/sample, n = 2).

Table 2. Molecular characteristics of 15 representative Clostridium difficile strains isolated from 13 of 214 retail meat packages tested in Canada, 2006*.

| Type† | % (no.) | Toxin genes‡ | tcdC deletion | Toxinotype | PFGE§ | Product–culture | Month | Province |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M26 | 23.1 (3) | A–B–, cdtB– | NA | Nontypeable | Unnamed | VC–C3 | Feb | QC |

| – | GB–C2 | Jan | ON | |||||

| – | GB–C2 | Jun | SK | |||||

| 077¶ | 23.1 (3) | A+B+, cdtB– | No | 0 | NAP2 | GB–C3 | Jan | QC |

| – | GB–C1 | Jan | ON | |||||

| – | GB–C3 | Jan | QC | |||||

| J¶ | 23.1 (3) | A+B+, cdtB+ | 18 bp | III | NAP1 | GB–C4 | May | ON |

| NAP1a | GB–C4 | Jun | ON | |||||

| – | VC–C4 | Feb | QC | |||||

| 014¶ | 15.4 (2) | A+B+, cdtB– | No | 0 | NAP4 | GB–C1 | May | QC |

| – | GB–C2 | Jan | QC | |||||

| C | 7.7 (1) | A+B+, cdtB– | No | – | – | GB–C1 | Jan | ON |

| F | 7.7 (1) | A-B+, cdtB– | No | VIII | NAP9 | GB–C2 | Jan | QC |

| H | 7.7(1) | A+B+, cdtB- | No | 0 | Unnamed | GB – C1 | Jun | QC |

| K | 7.7(1) | A+B+, cdtB+ | 18 bp | III | NAP1-r | VC–C2 | Aug | QC |

*PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; NA, not amplified because it lacks pathogenicity locus; VC, veal chops; GB, ground beef; C1, rinsate/TCDMNB; C2, meat/TCDMNB; C3, meat/TCDMNB duplicate; C4, meat/TCFFB; QC, Québec; ON, Ontario; SK, Saskatchewan; –, not performed. †Bidet’s PCR ribotyping method (9); 077 and 014; representative ribotypes with international nomenclatures assigned by Dr Jon Brazier, University of Wales, Wales, in a previous study (11). M26, non-toxigenic Canadian meat ribotype lacking pathogenicity locus (pers. com., M. Rupnik, University of Maribor, Slovenia) (5). ‡A, B; tcdA and tcdB genes. cdtB, binding segment of binary toxin; – and + superscripts indicate absence or presence of the gene. tcdC gene: no deletions (≈345 bp); 18 bp, deletion type B/C (8). §Nomenclature at the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA. NAP1, North America PFGE type 1. ¶Meat PCR ribotypes matching concurrent local and international human ribotypes (2,3). Note that 28 C. difficile isolates initially identified were grouped into 15 strains based on molecular characteristics and source of origin; 2 meat samples simultaneously harbored 2 strains.

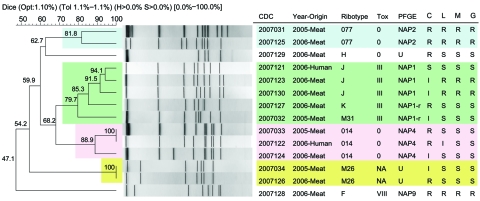

PFGE confirmed that selected meat and human PCR ribotypes were identical (Figure 2). Fluoroquinolone and clindamycin resistance was common (41.6%–58.3%) among isolates tested (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)–SmaI dendogram of Clostridium difficile isolates of meat and human origin in Canada. Representative PCR ribotypes 077, 014, M31, and M26 are of meat origin from 2005 (4,11). PCR ribotype designations are described in Table 2. Note the genetic similarity (94.1%–100%) and antimicrobial resistance profiles between human and meat isolates, especially PCR ribotypes 014 and J. Also note the genetic similarity (81.8%–100%) between meat isolates from 2005 and 2006 for multidrug-resistant epidemic PCR ribotype 077, clindamycin-variable, PCR ribotype 014, and nontoxigenic PCR ribotype M26. Resistance to all 4 antimicrobial drugs was observed in meat isolates of ribotypes 077 and F, which also yielded the highest level of clindamycin resistance (>256 µL/mL; breakpoint: >6 µL/mL). The breakpoints for moxifloxacin (12) were also used for levofloxacin and gatifloxacin. R (resistant), S (susceptible), and I (intermediate) represent antimicrobial profiles. CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NAP, North America PFGE type; NAP1-r, NAP-related strain; Tox, toxinotyping nomenclature (M. Rupnik, Maribor, Slovenia); U, unnamed.

Conclusions

In contrast to our first study (4), this study evaluated the genetic diversity of C. difficile in retail meats in a large area of Canada and tested 1–2 samples per store to prevent clustering. Thus, the overall prevalence observed (6.1%) was lower than that of previous studies in Canada (20%) (5) and the United States (42%) (13). Although different sampling and culture methods may account for the different prevalences, taken altogether, these studies support recent concerns regarding food safety.

Duplicate cultures, irrespective of method, could yield higher rates of C. difficile recovery from meat. However, the sensitivity of duplicate testing of meat is still suboptimal (46.2%–61.5%) compared with the sensitivity reached by one of our methods (4) in human stool samples (>95%) (6). Suboptimal performance might be due to reduced culture selectivity and nonhomogeneous distribution or a low number of spores.

In addition to cross-contamination at slaughter and during processing, it is possible that contamination of muscle tissue with C. difficile spores occurs preharvest. In horses, Clostridium spores have been recovered from muscle tissue in healthy horses (14), and a recent muscle sample yielded C. difficile in a healthy cow (unpub. data). Translocation from the intestines and deposition of dormant spores in muscle are reasonable assumptions that need investigation.

The increased recovery of C. difficile from meat in winter suggests that a seasonal component might exist. This component is currently uncertain, but a possible epidemiologic link between this observation and the seasonality observed in human disease (15) and the high rate of C. difficile toxins in calves in winter (11) requires further elucidation.

The C. difficile genotypes identified in this and other studies (especially the NAP1 clone and PCR ribotypes 077 and 014) (3,4,11) provide further molecular evidence that spore dissemination through foods should be considered. Although ingestion of spores does not necessarily imply infection, this study supports the potential for foodborne transmissibility and raises questions about possible seasonality.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joyce Rousseau for invaluable technical assistance, William Sears for statistical support, and the reviewers for their suggestions.

This study was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Biography

Dr Rodriguez-Palacios is currently at the Food Animal Health Research Program, Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, The Ohio State University, where he is studying the ecology and epidemiology of C. difficile.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Rodriguez-Palacios A, Reid-Smith RJ, Staempfli HR, Diagnault D, Janecko N, Avery BP et al. Possible seasonality of Clostridium difficle in retail meat, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2009 May [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/15/5/802.htm

References

- 1.McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, Owens RC Jr, Kazakova SV, Sambol JP, et al. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2433–41. 10.1056/NEJMoa051590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin H, Willey B, Low DE, Staempfli HR, McGeer A, Boerlin P, et al. Characterization of Clostridium difficile isolated from patients in Ontario, Canada, from 2004 to 2006. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2999–3004. 10.1128/JCM.02437-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbut F, Mastrantonio P, Delmee M, Brazier J, Kuijper E, Poxton I. European Study Group on Clostridium difficile (ESGCD). Prospective study of Clostridium difficile infections in Europe with phenotypic and genotypic characterisation of the isolates. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:1048–57. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez-Palacios A, Staempfli HR, Duffield T, Weese JS. Clostridium difficile in retail ground meat, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:485–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian integrated program for antimicrobial resistance surveillance (CIPARS) 2005. [cited 2008 Jan 20]. Available from http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cipars-picra/index-eng.php

- 6.Arroyo LG, Rousseau J, Willey BM, Low DE, Staempfli H, McGeer A, et al. Use of a selective enrichment broth to recover Clostridium difficile from stool swabs stored under different conditions. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5341–3. 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5341-5343.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemee L, Dhalluin A, Testelin S, Mattrat MA, Maillard K, Lemeland JF, et al. Multiplex PCR targeting tpi (triose phosphate isomerase), tcdA (toxin A), and tcdB (toxin B) genes for toxigenic culture of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5710–4. 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5710-5714.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spigaglia P, Mastrantonio P. Molecular analysis of the pathogenicity locus and polymorphism in the putative negative regulator of toxin production (TcdC) among Clostridium difficile clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3470–5. 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3470-3475.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bidet P, Barbut F, Lalande V, Burghoffer B, Petit JC. Development of a new PCR-ribotyping method for Clostridium difficile based on ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;175:261–6. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13629.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rupnik M, Dupuy B, Fairweather NF, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Just I, et al. Revised nomenclature of Clostridium difficile toxins and associated genes. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:113–7. 10.1099/jmm.0.45810-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez-Palacios A, Stampfli HR, Duffield T, Peregrine AS, Trotz-Williams LA, Arroyo LG, et al. Clostridium difficile PCR ribotypes in calves, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1730–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria; approved standard, seventh edition. CLSI document M11–A7; 2007:27(2) [cited 2008 May 17]. Available from http://www.clsi.org/source/orders/free/m11a7.pdf

- 13.Songer JG, Trinh HT, Thompson AD, Killgore GE, McDonald L, Limbago BM. Isolation of Clostridium difficile from retail meats. In: Second International Clostridium difficile Symposium; June 6–9, 2007; Maribor, Slovenia. Maribor (Slovenia): Marie Curie Conferences and Training Procedures; 2007. p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vengust M, Arroyo LG, Weese JS, Baird JD. Preliminary evidence for dormant clostridial spores in equine skeletal muscle. Equine Vet J. 2003;35:514–6. 10.2746/042516403775600569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Health Service for Wales. All-Wales mandatory Clostridium difficile surveillance- 2006 report [cited 2007 Jun 21]. Available from http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/page.cfm?orgid=379&pid=18490