Abstract

Reduced fecundity, associated with severe mental disorders1, places negative selection pressure on risk alleles and may explain, in part, why common variants have not been found that confer risk of disorders such as autism2 schizophrenia3 and mental retardation4. Thus, rare variants may account for a larger fraction of the overall genetic risk than previously assumed. In contrast to rare single nucleotide mutations, rare copy number variations (CNVs) can be detected using genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism arrays. This has led to the identification of CNVs associated with mental retardation4,5 and autism2. In a genome-wide search for CNVs associating with schizophrenia, we used a population-based sample to identify de novo CNVs by analysing 9,878 transmissions from parents to offspring. The 66 de novo CNVs identified were tested for association in a sample of 1,433 schizophrenia cases and 33,250 controls. Three deletions at 1q21.1, 15q11.2 and 15q13.3 showing nominal association with schizophrenia in the first sample (phase I) were followed up in a second sample of 3,285 cases and 7,951 controls (phase II). All three deletions significantly associate with schizophrenia and related psychoses in the combined sample. The identification of these rare, recurrent risk variants, having occurred independently in multiple founders and being subject to negative selection, is important in itself. CNV analysis may also point the way to the identification of additional and more prevalent risk variants in genes and pathways involved in schizophrenia.

The approach we used here was to use a large population-based discovery sample to identify de novo CNVs, followed by testing for association in a sample of patients with schizophrenia and psychoses (phase I) and finally replicating the most promising variants from phase I in a second larger sample (phase II). The discovery phase, where we searched for de novo CNVs, enriches for those regions that mutate most often. If the CNVs identified are in very low frequency in the population despite relatively high mutation rate (>1/10,000 meiosis), they are likely to be under negative selection pressure. Such variants may confer risk of disorders that reduce the fecundity of those affected.

To uncover de novo CNVs genome-wide we analysed data from a population-based sample (2,160 trios (two parents and one offspring) and 5,558 parent-offspring pairs, none of which was known to have schizophrenia; Supplementary Table 1), providing information on 9,878 transmissions. Of the 66 de novo CNVs identified, 23 were flanked by low copy repeats (LCRs) and nine had a LCR flanking only one of the deletion breakpoints. Of the remaining 34 CNVs (not flanked by LCRs), 27 were only found in a single control sample (the discovery trio) out of the 33,250 tested, whereas 18 out of the 23 CNVs flanked by LCRs were found at a higher frequency in the large control sample (Supplementary Table 2).

The 66 CNVs were tested for association in our phase I sample of 1,433 patients with schizophrenia and related psychoses and 33,250 controls from the SGENE consortium (http://www.sgene.eu/). For eight of the 66 CNVs tested, at least one schizophrenia patient carried the CNV (Supplementary Table 3), and for three large deletions, nominal association with schizophrenia and related psychoses was detected (uncorrected P-value<0.05, Table 1). The three deletions nominally associating with schizophrenia in the first sample (Table 1) were followed up in up to six samples comprising a total of 3,285 cases and 7,951 controls (Table 2). All three deletions, at 1q21.1, 15q11.2 and 15q13.3, significantly associate with schizophrenia and psychosis in the combined sample with high odds ratio (OR) (P=2.9×10−5, OR=14.83; P=6.0×10−4, OR=2.73; and P=5.3×10−4, OR=11.54, respectively). Removing cases with psychosis, other than ’diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders’ and “research diagnostic criteria’ defined schizophrenia (in total 147 cases: 39 with unspecified functional psychosis, 86 with schizoaffective disorder, 10 with schizophreniform and 12 with persistent delusional disorders; Supplementary Information), gave comparable results for the 1q21.1 deletion (P=2.31×10−5, OR=15.44), whereas the association for 15q11.2 and 15q13.3 deletions was no longer significant (P=9.57×10−4, OR=2.66 and P=1.02×10−3, OR=11.29, respectively (uncorrected for 66 tests)). Historically, classification schemes tend to group diseases by their signs and symptoms. There is, however, no reason why the phenotypes associating with a particular CNV should be confined to the current nosological boundaries of any single psychiatric disorder. Our findings, in this respect, resemble those from the 16p11.2 deletion2 and the translocation disrupting the DISC1 gene in a large Scottish pedigree6 and support the idea that the same mutation can increase the risk of a broad range of clinical psychopathology. It is therefore worth noting that among the eight controls carrying the 15q13.3 deletion there is one autistic individual (there are samples from 299 autistic individuals among the 39,800 control samples genotyped for this CNV).

Table 1. Nominal association of deletions at 1q21.1, 15q11.2 and 15q13.3 with schizophrenia and related psychoses in the phase I sample.

| Locus | Chromosome 1: 144.94-146.29 (Mb) | Chromosome 15: 20.31-20.78 (Mb) | Chromosome 15: 28.72-30.30 (Mb) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | |

| Iceland | 1 of 646 | 8 of 32,442 | 4 of 646 | 58 of 32,442 | 1 of 646 | 7 of 32,442 |

| Scotland | 2 of 211 | 0 of 229 | 2 of 211 | 0 of 229 | 1 of 211 | 0 of 229 |

| Germany | 1 of 195 | 0 of 192 | 3 of 195 | 0 of 192 | 1 of 195 | 0 of 192 |

| England | 0 of 105 | 0 of 96 | 1 of 105 | 0 of 96 | 0 of 105 | 0 of 96 |

| Italy | 0 of 85 | 0 of 91 | 0 of 85 | 0 of 91 | 0 of 85 | 0 of 91 |

| Finland | 0 of 191 | 0 of 200 | 0 of 191 | 1 of 200 | 0 of 191 | 0 of 200 |

| OR | 8.68 (1.02, 49.76) | 3.90 (1.42, 9.37) | 8.94 (0.79, 58.15) | |||

| P-value | 0.024 | 0.007 | 0.040 | |||

Three deletions show nominal association with schizophrenia and related psychoses in the first sample of 1,433 patients and 33,250 controls. These deletions are large: the 1q21 deletion spans approximately 1.38 Mb, the one on 15q11.2 approximately 0.47 Mb and the one on 15q13.3 approximately 1.57 Mb. P-values (uncorrected for the 66 tests) are from the exact Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test and are two-sided. Coordinates are based on Build 36 assembly of the human genome. 95% confidence intervals are given within brackets.

Table 2. Significant association of deletions at 1q21.1, 15q11.2 and 15q13.3 with schizophrenia and related psychoses in the combined samples.

| Locus | Chromosome 1: 144.94-146.29 (Mb) | Chromosome 15: 20.31-20.78 (Mb) | Chromosome 15: 28.72-30.30 (Mb) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | |

| Germany | 2 of 911 | 0 of 1,297 | 3 of 911 | 4 of 1,297 | 0 of 911 | 0 of 1,297 |

| Scotland | 2 of 451 | 0 of 441 | 5 of 451 | 1 of 441 | 0 of 451 | 0 of 441 |

| The Netherlands | 0 of 806 | 0 of 4,039 | 4 of 806 | 12 of 4,039 | 3 of 806 | 1 of 4,039 |

| Norway | 0 of 237 | 0 of 272 | 0 of 237 | 0 of 272 | 1 of 237 | 0 of 272 |

| Denmark* | 3 of 442 | 0 of 1,437 | 4 of 442 | 3 of 1,432 | 0 of 375 | 0 of 501 |

| China* | 0 of 438 | 0 of 463 | 0 of 438 | 0 of 463 | NA | NA |

| Phase II | ||||||

| OR | ∞ (2.85, ∞) | 2.18 (1.01, 4.60) | 16.47 (1.52, 833.38) | |||

| P-value | 5.6×10−4 | 0.032 | 7.9×10−3 | |||

| Phase I and II | ||||||

| OR | 14.83 (3.55, 60.40) | 2.73 (1.50, 4.89) | 11.54 (2.53, 49.58) | |||

| P-value | 2.9×10−5 | 6.0×10−4 | 5.3×10−4 | |||

The three deletions nominally significant in phase I were tested for association in follow up samples from Germany, Scotland, The Netherlands, Denmark, Norway and China. All three deletions associate with schizophrenia and related psychoses in the combined phase I and II samples (the multiple testing significance threshold is 0.05/66=7.6×10−4). P-values in the table (uncorrected for the 66 tests) are from the exact Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test and are two-sided. Coordinates are based on Build 36 assembly of the human genome. 95% confidence intervals are given within brackets. NA, not analysed.

Samples were measured using Taqman assays. Samples with CNVs identified by measuring gene dosage by a Taqman assay were verified and confirmed by genotyping the respective samples using the HumanCNV370 chip. A limited amount of DNA was available for genotyping the Chinese samples.

Eleven out of the 4,718 cases tested (0.23%) carry the 1q21.1 deletion compared to eight of the 41,199 controls tested (0.02%). In seven of the eleven patients, the deletion spans about 1.35 megabases (Mb) (chromosome 1: 144,943,150-146,293,282). Four cases have a larger form of the deletion (Supplementary Table 4). The larger form contains the shorter form and extends to 144,106,312 Mb, about 2.19 Mb (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Seven of the eight Icelandic controls have the shorter form of the deletion and one control has the longer form. Previously reported 1q21.1 deletions in two cases of mental retardation5,7 two autistic individuals2 and one schizophrenia case8 are consistent with the shorter form of the deletion.

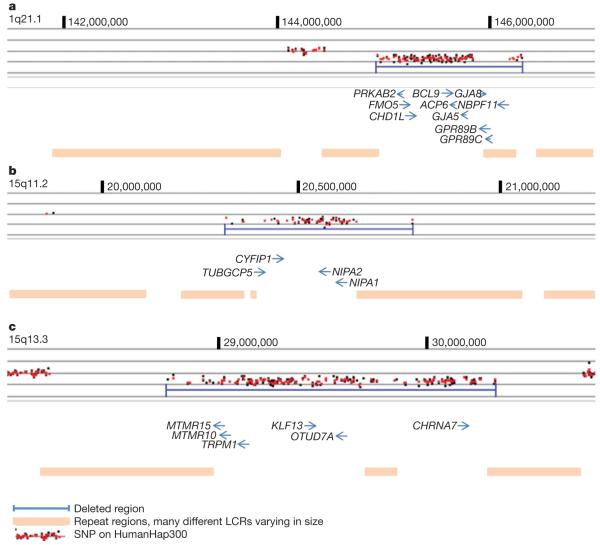

Figure 1. The genomic architecture of the 1q21.1, 15q11.2 and 15q13.3 deletions.

a, DosageMiner output showing the shorter form of the 1q21 deletion (marked in blue). Ninety-nine SNPs on the HumanHap300 chip are affected by the deletion which spans 1.38 Mb. b, DosageMiner output showing the 15q11.2 deletion (marked in blue). Fifty-four SNPs on the HumanHap300 chip are affected by the deletion which spans 470 kb. c, DosageMiner output showing the 15q13.3 deletion (marked in blue). One-hundred-and-sixty-six SNPs on the HumanHap300 chip are affected by the deletion which spans 1.57 Mb. Genes affected by the deletions are shown (coordinates are based on Build 36 of the human genome and positions of genes derived from the UCSC genome browser). LCRs flank all three deletions (Supplementary Figs 1, 3 and 4).

The 1.35 Mb deleted segment common to both the large and the small form of the 1q21.1 deletion is gene rich (Fig. 1a). The GJA8 gene has previously been reported as associated with schizophrenia9. This gene is located in a repeat region within the boundary of the 1.35 Mb deletion segment and contains no single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers on the HumanHap300 chip. In at least four reports10-13 the 1q21 locus has been linked to schizophrenia; however, the deletion is rare and therefore unlikely to account for much of the linkage previously reported. Analysis of cells from a case with the 1q21.1 deletion and a case with the reciprocal duplication, using fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2), show that other rearrangements, such as chromosomal translocations, are unlikely to be associated with the deletion.

The deletion at 15q11.2 was significant in the combined schizophrenia and related psychosis sample (Table 2). In the combined sample 26 of 4,718 cases (0.55%) carry the deletion compared with 79 of 41,194 controls (0.19%). The deletion spans approximately 470 kb (chromosome 15: 20,306,549-20,777,695) and several genes are deleted (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 3). A single case with mental retardation and severe speech impairment has previously been reported with the 15q11.2 deletion14. Although the region is not imprinted, it is deleted in a minority of cases of Angelman syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome. Recent analysis shows that Angelman syndrome cases with class I deletions (includes the 15q11.2 deletion) are significantly more likely to meet criteria for autism15. Prader-Willi syndrome type I deletions are associated with increased risk of preservative/obsessive compulsive behaviour, deficits in adaptive skills and lower intellectual ability. Thus, the autistic features in Angelman syndrome and the preservative behaviour of Prader-Willi syndrome may arise from deletion of the genes in the proximal portion of the region, the site at the breakpoints of the chromosome 15 deletions found in the current study. The gene in the 15q11.2 deletion region that is most likely to be responsible for both the autistic and obsessive compulsive features observed in Angelman syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome with class one deletions, and the schizophrenia phenotype in this study, is CYFIP1 (Fig. 1c). CYFIP1 interacts with fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) as well as with the Rho GTPase Rac1, which is involved in regulating axonal and dendritic outgrowth and the development and maintenance of neuronal structures. Over 30% of children with fragile X syndrome meet criteria for autism16 with highest rates observed in cases with Prader-Willi features without the deletion on 15q. Notably, the fragile X mutation results in a reduction in expression levels of the CYFIP1 gene17 and fragile X syndrome behavioural abnormalities resemble features of schizophrenia. Fragile X syndrome is caused by the complete loss of function of FMRP, whereas the hemizygous deletion of CYFIP1 would only cause partial disturbance of FMRP function, in which case an effect similar to that observed in fragile X in females and obligate carriers might be expected. These women have attentional deficit and extreme shyness and anxiety, and they may also present with psychiatric disturbances of which psychotic behaviour is the most frequent18,19.

The 15q13.3 deletion is also significantly associated with schizophrenia and related psychoses in the combined samples (Table 2). A total of 7 of 4,213 cases (0.17%) carry the deletion and 8 of 39,800 controls (0.02%). One of several affected genes (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 4), the α7 nicotinic receptor gene (CHRNA7), is targeted to axons by neuregulin 120 and has been implicated in schizophrenia21 and also in mental retardation22. Mice lacking the α7 subunit of the neural nicotinic receptor show a minor impairment in the matching-to-place task of the Morris water maze, taking longer to find the hidden platform than their wild-type controls. This suggests a role for CHRNA7 in working/episodic memory and a potential role for CHRNA7 in schizophrenia and its endophenotypes23.

On the HumanHap300 array, 99 SNPs are affected by the deletion on 1q21.1, 54 by the 15q11.2 deletion and 166 by the 15q13.3 deletion (Supplementary Tables 7-9). Significant association was not found with schizophrenia and SNPs at the three deletion loci. However, rare variants at these loci might still associate with schizophrenia as they are not tagged by markers on the HumanHap300 chip. Finding such variants probably requires re-sequencing of the deleted interval in a large sample of cases and testing identified variants for enrichment in schizophrenia.

From available records, we see that cases carrying the 1q21.1, 15q11.2 and 15q13.3 deletions have clinical response rates to neuroleptics that are comparable to the general schizophrenic patient population. Family history of schizophrenia in close relatives is also comparable to other patients with schizophrenia in our sample (although these affected relatives are not available for genotyping) and there is no obvious sex bias, as both males and females carrying the deletions are affected. Assessment of cognitive abilities was only available for a fraction of the cases with deletions. None of the cases carrying the three deletions was known to be mentally retarded; however, three cases carrying the 1q21.1 deletion had learning disabilities and two controls had dyslexia (Supplementary Tables 4-6).

The frequency of the deletions identified here is comparable to the frequency of the velo-cardio-facial syndrome (VCFS) deletion on 22q11, previously shown to associate with schizophrenia24,25. The large VCFS deletion was present in 8 out of 3,838 cases tested (0.2%) (Icelandic (n=1), Scottish (n=5), Dutch (n=1) and German (Bonn, n=1)) but was absent in 39,299 controls (P=4.2×10−5, OR=∞).

The CNVs associating with schizophrenia on chromosome 1q21.1, 15q11.2 and 15q13.3 show less clustering in the Icelandic population than would be expected if they were selectively neutral (Supplementary Information). All these CNVs are flanked by large and complex LCR sequences (Supplementary Figs 1, 3 and 4). The LCR can mediate non-allelic homologous recombination, which may result in loss or gain of genomic segments. Through this process CNVs under negative selection can be maintained at low frequency in the population. Other mechanisms for generating rearrangements26 cannot be excluded. For none of the deletions associated with schizophrenia are we able to pinpoint which LCRs are mediating the non-allelic homologous recombination owing to the complexity of the regions flanking the deletions. Notably, the same CNVs are implicated in schizophrenia and autism and an important area for future study is to determine whether deletions conferring schizophrenia-like syndrome should be considered as classical schizophrenia or new microdeletion syndromes.

In the present study we searched for variants that we think are most likely to confer risk of schizophrenia, namely large recurrent CNVs likely to be under negative selection pressure, rather than testing a large number of selectively neutral CNVs. It is important to identify all recurrent CNVs under negative selection and test those variants for enrichment in well powered samples of schizophrenia cases as well as cases of autism and mental retardation. To determine diagnostic and treatment implications it is also important to study the CNVs conferring risk with respect to drug response, disease progression and symptomatology. Two of the three deletions described here confer high risk of schizophrenia (OR>11), whereas the third is more common and with more modest risk (OR=2.73). Already identified CNVs associating with schizophrenia may point the way towards underlying pathogenic pathways in the disease; furthermore, high-resolution scans for copy number variants may well identify more CNVs associated with the disease, and given the high odds ratio, these are likely to be clinically useful in diagnosis and risk assessment. Although the CNVs reported here only account for a very small fraction of the genetic risk of schizophrenia, this is an exciting step towards what promises to be a fruitful field for further investigation.

Note added in proof: Samples from the University of Aberdeen were genotyped independently by the International Schizophrenia Consortium28.

METHODS SUMMARY

Subjects

This study was approved by the National Bioethics Committees or the Local Research Ethical Committees and Data Protection Commissions or laws in the respective countries, Iceland, United Kingdom (Scotland and England), Germany, Finland, Italy, Denmark, Norway, The Netherlands and China. Informed consent was obtained from all patients (Supplementary Information). Of the 4,718 genotyped cases, 4,571 were diagnosed with schizophrenia, 39 with unspecified functional psychosis, 86 with schizoaffective disorder, 10 with schizophreniform and 12 with persistent delusional disorders (Supplementary Information).

Genotyping

The SGENE samples (samples from six European groups, http://www.sgene.eu/) typed on the HumanHap300 chip were used in phase I of the study (Table 1). In phase II, (Table 2) CNV data were derived from the HumanHap300 chip, the HumanHap550 chip, the Affymetrix GeneChip(r) GenomeWide SNP 6.0 or dosage measured using Taqman probes27. The Scottish samples in Table 2 were typed at Duke University (HumanHap550) in collaboration with GlaxoSmithKline as were 420 of the German samples, all from Munich (HumanHap300). The remaining CNV data (HumanHap550) from Germany (Table 2, n=491) were obtained from the University of Bonn. Norwegian samples (Affymetrix GeneChip(r) GenomeWide SNP 6.0 array) were analysed using the Affymetrix Power Tools 1.8.0. Dosage data for Danish and Chinese samples were generated at deCODE using Taqman assays27. Samples with CNVs were verified by genotyping respective samples using the HumanCNV370 chip.

Statistical analysis

For the genome-wide study of de novo CNV associating with schizophrenia the significance threshold was set at 7.6×10−4 which is approximately 0.05/66, the number of de novo CNVs identified and tested. All P-values are two-sided and there is no overlap between samples in Tables 1 and 2. An exact conditional Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test (conditional on the strata margins) was used to test for association of schizophrenia and the various CNVs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the subjects and their relatives and staff at the recruitment centres. This work was sponsored by EU grant LSHM-CT-2006-037761 (Project SGENE), Simons Foundation and R01MH71425-01A1. Genotyping of the Dutch samples was sponsored by NIMH funding, R01 MH078075. This work was also supported by the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation and the National Genomic Network (NGFN-2) of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). M.M.N. received support from the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung. We are grateful to S. Schreiber and M. Krawczak for providing genotype data for PopGen controls, and to K.-H. Jöckel and R. Erbel for providing control individuals from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. We thank L. Priebe and M. Alblas for technical assistance and analysis of CNV data from Bonn.

APPENDIX

METHODS

De novo CNV analysis

To uncover de novo CNVs genome-wide we analysed data from a population-based sample of 2,160 trios and 5,558 parent-offspring pairs, totalling 9,878 transmissions. Samples were genotyped using the Illumina HumanHap300 or the HumanCNV370 chips. To identify de novo deletions, we combined two complementary methods: DosageMiner, a Hidden Markov Model algorithm based on intensity data that is similar to that reported previously29 and a procedure using inheritance errors and the neighbouring genotype configurations comparable to that described previously30. When only one parent was typed, using genotype information allowed us to identify deletions as putatively de novo by assessment of regional parental heterozygosity. To identify de novo duplications we analysed CNV data from the 2,160 trios using DosageMiner.

CNVs in phase 1 were identified by using DosageMiner, software developed by deCODE genetics, and loss of heterozygosity analysis. CNV events stand out in the data from two perspectives. First, all sample intensities for SNPs/probes within a CNV should be increased or decreased relative to neighbouring SNPs/probes that are not in a CNV region; second, CNVs can be detected from the transmission from parent to child. To determine deviations in signal intensity we start by normalizing the intensities. The normalized intensities for each colour channel were determined by a fit of the following equation: log (xij)=f(αi,gc(j)) + μj,gen(i,j) + βi + εij, where i is sample index, j is SNP index, xij is colour intensity for sample i in SNP j, gc(j) is an indicator of G+C content around SNP j, f is a smooth function of G+C content, αi are sample-specific parameters for G+C content, gen(i,j) is the genotype for sample i for SNP j, μj,gt is the SNP effect for genotype gt and SNP j, βi is sample effect, and εij is the unexplained part of the signal, including noise. The same model with another set of parameters is used for the other colour yij. A generalized additive model31 is used to fit the smooth function f. After fitting the model, the data are normalized by removing the systematic model components. We consider a region to be a deletion/duplication if the average intensity over at least ten markers in a region falls below/above an empirically determined threshold.

To identify regions demonstrating loss of heterozygosity (LOH), markers are split into three classes: (1) shows LOH; (2) inconsistent with LOH; and (3) consistent with LOH. Class 3 is further split into two subclasses: (a) consistent with transmitted LOH; (b) consistent with de novo LOH. A marker shows LOH if a child is homozygous for one allele and a parent is homozygous for the other allele. A marker is inconsistent with LOH if the child is heterozygous. A marker is consistent with LOH if the child is homozygous and the parent is homozygous for the same allele or heterozygous. In case the parent is homozygous for the same allele as the child, the marker is consistent with transmitted LOH, and in case the parent is homozygous for the other allele, the marker is only consistent with de novo LOH.

A stretch containing a single marker showing LOH is likely to be due to a genotyping error, but because our genotyping error rate is low and independent of position on the genome, the occurrence of more than one marker showing LOH in a consecutive stretch on the genome is more likely to be evidence of a deletion in the child. We consider a region to be a putative deletion if at least two markers are showing LOH and de novo if consistent with de novo LOH.

We analysed 9,878 offspring-parent pairs consisting of a total of 7,718 offspring and 7,121 parents. Using LOH analysis we define a candidate deleted region if more than one marker shows inheritance error within a region of homozygous markers. We identified a total of 270 candidate de novo deletions using this approach. Of these, 80 belong to six distinct individuals which all had multiple regions identified as de novo deletions on the same chromosome. On further inspection of the data for these individuals we concluded that they were examples of uniparental disomy. Once these individuals were removed, the remaining 190 putative de novo deletions were compared with the output of DosageMiner, and 55 were consistently called deletions by both approaches. These 55 de novo deletions represent 51 loci (Supplementary Table 3). In addition 15 large duplications, of 20 or more consecutive markers, were also identified in the trio sample by DosageMiner (Supplementary Table 3).

Dosage measurements using Taqman assays

The Danish and Chinese samples in Table 2 were typed using Taqman assays27. The 1q21.1 assay (PRK assay) and 15q11.2 assay (NIPA2 assay) were designed using Primer Express software. Applied Biosystems provided FAM-labelled probes for the assay which were run as described previously27. For the reference assay we used a probe in the CFTR gene and used the same protocol. The second reference assay, RNASEP ready to use assay, was supplied by Applied Biosystems. Samples identified with deletions or duplications by the Taqman dosage measurements were confirmed by typing the sample on the Illumina HumanCNV370 array.

Probe and primers used for the 1q21.1 assay: 6FAM-CCTGCTGTGTGGGCT-MGB (minor groove binder), PRK-F, CCTTCAGACCAGCGGATAACA and PRK-R, CATGGCAGCAGGATTTGGA. Probe and primers used for the 15q11.2 assay: 6FAM-CAGAGCAGATTGTTATGTAC-MGB, NIPA2-F, GACT GAAAACGCGCCGATT and NIPA2-R, CCATGGACAGACAAACATTCTTG. Probe and primers used for the CFTR assay: 6FAM-ATTAAGCACAGTGGAAGAA-MGBNFQ (minor groove binder non-fluorescent quencher), CFTR-F, AACTGGAGCCTTCAGAGGGTAA and CFTR-R, CCAGGAAAACTGAGAACAGAATGA.

Plates were sealed with optical adhesive cover (Applied Biosystems) and the real-time PCR carried out on an ABI 7900 HT machine for 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C starting out with an initial step of 10 min at 95 °C.

- 29.Colella S, et al. QuantiSNP: an objective Bayes Hidden-Markov Model to detect and accurately map copy number variation using SNP genotyping data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2013–2025. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conrad DF, Andrews TD, Carter NP, Hurles ME, Pritchard JK. A high-resolution survey of deletion polymorphism in the human genome. Nature Genet. 2006;38:75–81. doi: 10.1038/ng1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Generalized additive models. Stat. Sci. 1986;1:297–310. doi: 10.1177/096228029500400302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

The authors declare competing financial interests: details accompany the full-text HTML version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

†Genetic Risk and Outcome in Psychosis (GROUP): René S. Kahn, Don H. Linszen, Jim van Os, Durk Wiersma, Richard Bruggeman, Wiepke Cahn, Lieuwe de Haan, Lydia Krabbendam, Inez Myin-Germeys

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

References

- 1.Vogel HP. Fertility and sibship size in a psychiatric patient population. A comparison with national census data. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1979;60:483–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1979.tb00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss LA, et al. Association between microdeletion and microduplication at 16p11.2 and autism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:667–675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shifman S, et al. Genome-wide association identifies a common variant in the reelin gene that increases the risk of schizophrenia only in women. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu X, et al. Clinical implementation of chromosomal microarray analysis: summary of 2513 postnatal cases. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Vries BB, et al. Diagnostic genome profiling in mental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;77:606–616. doi: 10.1086/491719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millar JK, et al. Disruption of two novel genes by a translocation co-segregating with schizophrenia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1415–1423. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp AJ, et al. Discovery of previously unidentified genomic disorders from the duplication architecture of the human genome. Nature Genet. 2006;38:1038–1042. doi: 10.1038/ng1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh T, et al. Rare structural variants disrupt multiple genes in neurodevelopmental pathways in schizophrenia. Science. 2008;320:539–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1155174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ni X, et al. Connexin 50 gene on human chromosome 1q21 is associated with schizophrenia in matched case control and family-based studies. J. Med. Genet. 2007;44:532–536. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.047944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brzustowicz LM, Hodgkinson KA, Chow EW, Honer WG, Bassett AS. Location of a major susceptibility locus for familial schizophrenia on chromosome 1q21-q22. Science. 2000;288:678–682. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurling HM, et al. Genomewide genetic linkage analysis confirms the presence of susceptibility loci for schizophrenia, on chromosomes 1q32.2, 5q33.2, and 8p21-22 and provides support for linkage to schizophrenia, on chromosomes 11q23.3-24 and 20q12.1-11.23. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:661–673. doi: 10.1086/318788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwu HG, Liu CM, Fann CS, Ou-Yang WC, Lee SF. Linkage of schizophrenia with chromosome 1q loci in Taiwanese families. Mol. Psychiatry. 2003;8:445–452. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng Y, et al. A two-stage linkage analysis of Chinese schizophrenia pedigrees in 10 target chromosomes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;342:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murthy SK, et al. Detection of a novel familial deletion of four genes between BP1 and BP2 of the Prader-Willi/Angelman syndrome critical region by oligo-array CGH in a child with neurological disorder and speech impairment. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2007;116:135–140. doi: 10.1159/000097433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers SJ, Wehner DE, Hagerman R. The behavioral phenotype in fragile X: symptoms of autism in very young children with fragile X syndrome, idiopathic autism, and other developmental disorders. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2001;22:409–417. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimitropoulos A, Schultz RT. Autistic-like symptomatology in Prader-Willi syndrome: a review of recent findings. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9:159–164. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nowicki ST, et al. The Prader-Willi phenotype of fragile X syndrome. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2007;28:133–138. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000267563.18952.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borghgraef M, Fryns JP, van den Berghe H. The female and the fragile X syndrome: data on clinical and psychological findings in 7 fra(X) carriers. Clin. Genet. 1990;37:341–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1990.tb03516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson NM, et al. Neurobehavioral characteristics of CGG amplification status in fragile X females. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1994;54:378–383. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320540418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hancock ML, Canetta SE, Role LW, Talmage DA. Presynaptic type III neuregulin1-ErbB signaling targets α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors to axons. J. Cell Biol. 2008;181:511–521. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman R, et al. Linkage of a neurophysiological deficit in schizophrenia to a chromosome 15 locus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:587–592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erdogan F, et al. Characterization of a 5.3 Mb deletion in 15q14 by comparative genomic hybridization using a whole genome “tiling path” BAC array in a girl with heart defect, cleft palate, and developmental delay. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2007;143:172–178. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandes C, Hoyle E, Dempster E, Schalkwyk LC, Collier DA. Performance deficit of α7 nicotinic receptor knockout mice in a delayed matching-to-place task suggests a mild impairment of working/episodic-like memory. Genes Brain Behav. 2006;5:433–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karayiorgou M, et al. Schizophrenia susceptibility associated with interstitial deletions of chromosome 22q11. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:7612–7616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy KC. Schizophrenia and velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Lancet. 2002;359:426–430. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07604-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JA, Carvalho CM, Lupski JRA. DNA replication mechanism for generating nonrecurrent rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. Cell. 2007;131:1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bieche I, et al. Novel approach to quantitative polymerase chain reaction using real-time detection: application to the detection of gene amplification in breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 1998;78:661–666. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981123)78:5<661::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The International Schizophrenia Consortium Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature07239. doi:10.1038/nature07239 (this issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.