Abstract

In this report we show that inactivation of the putative nitroreductase SA0UHSC_00833 (ntrA) increases the sensitivity of Staphylococcus aureus to S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) and augments its resistance to nitrofurans. S. aureus NtrA is a bifunctional enzyme that exhibits nitroreductase and GSNO reductase activity. A phylogenetic analysis suggests that NtrA is a member of a novel family of nitroreductases that seems to play a dual role in vivo, promoting nitrofuran activation and protecting the cell against transnitrosylation.

Staphylococcus aureus is a gram-positive pathogen responsible for a large number of human infections that range from mild to potentially lethal systemic infections. The rapidly increasing incidence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections, particularly among human immunodeficiency virus-infected and AIDS patients (1), reveals that the antibiotic of choice for the treatment of S. aureus is becoming ineffective and shows the need for using alternative compounds. Staphylococcus strains are sensitive to nitrofuran derivatives such as nitrofurazone and nitrofurantoin, which are utilized in the treatment of burns, skin grafts, and genitourinary infections (2). The action of nitrofurans is dependent on the presence of specific microbial enzymes, the nitroreductases, which catalyze the reduction of the drug, a step that is essential for its activation. The activation of nitroaromatic compounds by bacterial nitroreductases is also used as a cancer therapy, since the cytotoxic hydroxylamine derivative compounds are able to destroy tumors (5).

In microorganisms subjected to nitrosative stress, S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) is formed by reaction of NO with the intracellular glutathione. The GSNO formed reacts with thiol-containing proteins promoting thiol nitrosation, which modifies the function of proteins that are essential to many cellular processes. To control the level of S-nitrosylated proteins, organisms use GSNO reductases, namely, the ubiquitous glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase, also known as class III alcohol dehydrogenase (6). However, GSNO is also a NADPH-dependent oxidizing substrate of other enzymes such as the thioredoxin system, glutathione peroxidase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, and xanthine oxidase, indicating that GSNO reductase activity is frequently associated with other enzymatic activities (3, 4, 7, 10).

Our microarray studies revealed that the staphylococcal gene SA0UHSC_00833 of S. aureus NCTC 8325 encoding a putative nitroreductase is induced by GSNO. Hence, we have analyzed the in vivo role of this protein in the metabolism of GSNO and nitrofurans and performed biochemical characterization of the recombinant protein SA0UHSC_00833 (named NtrA).

S. aureus NtrA is involved in GSNO metabolism.

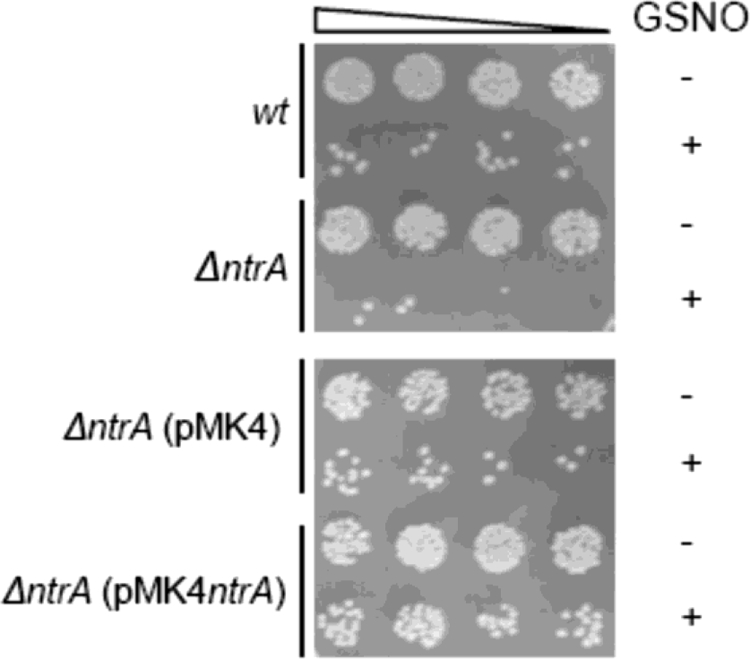

In a DNA microarray study of S. aureus NCTC 8325, we detected that GSNO significantly upregulates the SA0UHSC_00833 gene (herein named ntrA), which encodes a putative nitroreductase (our unpublished data). To perform quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR analysis, cells of S. aureus NCTC 8325 were grown in LB medium to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4 and were treated for 10 min with GSNO (150 μM). The bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material. Real-time PCR experiments were performed with a LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR green I kit (Roche Applied Science), using 400 ng of cDNA prepared from total RNA and 0.5 μM of primers SANrEco and SaNrNhe for the SA0UHSC_00833 (ntrA) gene and primers 16S_Fwd and 16S_Rev for S. aureus 16S rRNA. The results confirm that GSNO causes a strong (13.4- ± 3.8-fold) transcriptional induction of the ntrA gene. The expression of SACOL0874, a homolog gene in S. aureus COL, was also reported to be induced by nitrosative stress conditions (8). Since these results suggest the involvement of the ntrA gene in nitrosative metabolism, a strain defective in the gene was constructed and analyzed. For construction of the mutant, the S. aureus NCTC 8325 SA0UHSC_00833 (ntrA) gene was PCR amplified using SA0833MutEco and SA0833MutBam oligonucleotides, ligated to pSP64D-E (pSP64-SA0833), electroporated into S. aureus RN4220, and selected on tryptone soy agar plates containing erythromycin (10 μg/ml). The correct integration of pSP64-SA0833 into the chromosome of S. aureus was confirmed by PCR, and the generated mutant strain was designated LMSA833. For the GSNO sensitivity tests, the wild-type strain and LMSA833 (the ΔntrA mutant) were grown overnight in tryptone soy broth (TSB), inoculated in fresh LB medium, and exposed for 1 h to GSNO (100 μM). The cultures were treated for another 4 h with 1 mM of GSNO, and serial dilutions were spotted onto tryptone soy agar plates. After overnight incubation, the plates revealed that the ΔntrA mutant exhibited a higher degree of GSNO inhibition than the parental strain. Furthermore, expression of NtrA from the pMK4 plasmid restored the wild-type phenotype (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, we did not observe enhanced susceptibility of the ntrA mutant when using NO gas (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Sensitivity to GSNO of the S. aureus ΔntrA mutant. S. aureus wild type (wt), the ΔntrA strain, and ΔntrA strains harboring pMK4ntrA or the vector alone were grown in LB medium and treated with 1 mM of GSNO (+) or left untreated (−). Sensitivity tests were assayed after 4 h of GSNO treatment by plating on agar serial dilutions of the cultures.

The S. aureus ntrA mutant is more resistant to nitrofurans.

Since SA0UHSC_00833 is annotated as a putative nitroreductase, its role in the metabolism of nitrofurans was also examined. To this end, overnight cultures of the S. aureus wild type (RN4220) and the ΔntrA mutant (LMSA833) grown in TSB were used to inoculate fresh LB medium supplemented with nitrofurantoin (20 μg/ml) or nitrofurazone (25 μg/ml). In the absence of antibiotics, the wild-type and mutant strains displayed similar growth kinetics. After the addition of nitrofurans, the growth of both strains was immediately inhibited. Whereas after 22 h the wild type showed limited recovery (recovery values of 17% and 9% for nitrofurantoin and nitrofurazone, respectively), the mutant strain had resumed growth at a rate similar to that of the untreated culture, exhibiting a recovery of 67% for cells treated with nitrofurantoin and of 71% for cells submitted to nitrofurazone. Furthermore, cells of the ntrA mutant strain expressing NtrA from a multicopy plasmid bearing only the ntrA gene regained the sensitivity to nitrofurans with a phenotype similar to the phenotype observed for the wild-type strain (data not shown). In conclusion, the presence of an active ntrA gene product contributes to the sensitivity of S. aureus to nitrofurans.

Mutation of ntrA decreases the nitroreductase activity of S. aureus.

The activity of cell extracts of the S. aureus wild type and the ntrA mutant strain were analyzed by following the reduction of nitrofurantoin and nitrofurazone through the use of NADH or NADPH as an electron donor. To this end, cells from TSB overnight cultures of the wild type and the ΔntrA mutant (LMSA833) were harvested, resuspended in cold 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (buffer A) (pH 7.6), and incubated with lysostaphin (50 μg/ml) at 37°C for 15 min. Following the addition of DNase (50 μg/ml), cells were centrifuged (13,000 × g) for 30 min at 4°C. The enzymatic assays were recorded using a Shimadzu UV-1700 spectrophotometer (at 25°C) following the decrease of the nitrofuran absorbance (for nitrofurazone, ɛ400 = 12,960 M−1 cm−1; for nitrofurantoin, ɛ420 = 12,000 M−1 cm−1). The mixture contained buffer A, nitrofuran, NADPH, or NADH (100 μM), and the reaction was initiated by the addition of the cell extract. The NADPH-dependent activity was found to be higher than NADH-dependent activity, and the higher activity values were measured when using nitrofurantoin. Inactivation of the ntrA gene of S. aureus led to a significant decrease in the nitrofurantoin and nitrofurazone reductase activity values (Table 1), which correlates with the increase in the nitrofuran resistance observed in the ntrA mutant strain.

TABLE 1.

Nitroreductase activity assayed in cell extracts of S. aureus wild-type and ntrA mutant (ΔntrA) strains

| Strain | Nitroreductase activity (nmol·min−1·mg−1 protein)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrofurantoin

|

Nitrofurazone

|

|||

| NADPH | NADH | NADPH | NADH | |

| Wild type | 9.5 ± 0.7 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.4 |

| ΔntrA | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

Values are means ± standard errors.

S. aureus NtrA protein reduces GSNO and nitrofurans.

To further characterize the function of the S. aureus NtrA, the protein was produced and characterized. Hence, the S. aureus NCTC 8325 SA0UHSC_00833 (ntrA) gene was amplified using two oligonucleotides, SA0833NheIEx and SA0833EcoRIEx (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), and cloned into pET28a(+), yielding pET28NtrA, which was transformed in Escherichia coli BL21-Gold(DE3). Cells were grown in LB medium with 30 μg of kanamycin/ml to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.3 and induced for 7 h with isopropyl-ß-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (500 μM). Since the NtrA protein produced contain a His tag, the soluble extract was loaded onto a HisTrap Hp column (GE Healthcare). Elution with ∼200 mM imidazole yielded a pure fraction of NtrA, as judged by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, which had an apparent molecular mass of ∼21 kDa. The GSNO reductase activity of S. aureus NtrA was measured in buffer A-S. aureus NtrA protein (0.6 μM)-NADPH (or NADH) (250 μM)-GSNO (50 to 400 μM). The reaction was initiated by the addition of GSNO and monitored following the oxidation of NAD(P)H (ɛ320 = 6,220 M−1 cm−1). Activity values were corrected, taking into account the reaction of GSNO with NAD(P)H. The kinetic data were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation by the use of SigmaPlot software. All values shown here represent the average results of at least two assays. The S. aureus NtrA enzyme was shown to be specific for GSNO, since no activity was seen for NO, S-nitrosocysteine, or S-nitrosohomocysteine. Kinetic analysis of the S. aureus NtrA gave a Km value (pH = 7.6) for GSNO of ∼181 μM (Table 2), a value which is lower than that measured for E. coli glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase (Km ∼ 700 μM [pH = 7]) (6), thus indicating a higher affinity of NtrA for this substrate. The nitroreductase activity of the purified S. aureus NtrA was also determined using nitrofurantoin and nitrofurazone (5 to 50 μM) as substrates and, as electron donors, NADPH or NADH (250 μM), which were used to initiate the reaction. Since S. aureus NtrA (0.6 μM) had previously been incubated with flavin mononucleotide or flavin adenine dinucleotide (5 μM), all activities were corrected by taking into account the chemical reduction of the nitrofuran compound generated by the same amount of flavin utilized in the protein mixture. We observed that whereas S. aureus NtrA incubated with flavin mononucleotide exhibited nitroreductase activity, no significant activity was measured when flavin adenine dinucleotide was incorporated into S. aureus NtrA. As observed for the GSNO reductase activity of S. aureus NtrA, the nitroreductase activities seen when using NADH or NADPH as a source of reducing equivalents were of the same order of magnitude (data not shown). The NADPH-dependent nitrofuran activity of S. aureus NtrA (Table 2) is within the range of values usually observed. In particular, the only nitroreductase from S. aureus that has been studied so far, the SA0UHSC_00366 protein (named NfrA), exhibits nitrofurazone- and nitrofurantoin-specific activities of 20 and 15 μmol·min−1·mg−1, respectively (12), and the E. coli NsfA nitroreductase has a specific activity of ∼80 μmol·min−1·mg−1 (9).

TABLE 2.

GSNO reductase and nitroreductase activity of S. aureus NtrA

| Enzyme | Km (μM) | Vmax (μmol·min−1·mg−1) | kcat (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSNO | 180.6 ± 43.4 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.2 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 18.8 ± 4.8 | 13.7 ± 1.5 | 22.8 |

| Nitrofurazone | 25.7 ± 5.8 | 15.3 ± 1.6 | 25.5 |

The bifunctional S. aureus NtrA belongs to a novel family of nitroreductases.

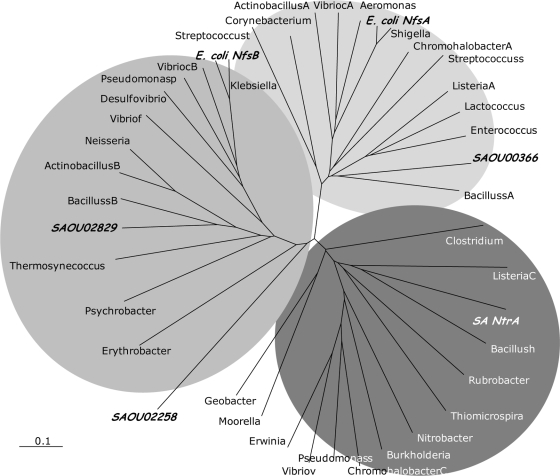

A search in the genome of S. aureus NCTC 8325 revealed that in addition to SA0UHSC_00833 (NtrA), three other genes encoding putative nitroreductases are present, namely, SA0UHSC_00366 (NfrA), SA0UHSC_02829, and SA0UHSC_02258. The gene products of the four S. aureus nitroreductases share low levels of sequence identities, which range between 4% and 11%. Since the E. coli nitroreductases are well characterized (11), we performed an amino acid sequence alignment with these enzymes which revealed that SA0UHSC_00366 (NfrA) shares the highest percentage of identity with E. coli b0851 (NfsA) and SA0UHSC_02829 with E. coli b0578 (NfsB), whereas SA0UHSC_00833 (NtrA) and SA0UHSC_02258 show less than 10% identity with the two E. coli nitroreductases. A search in the completed microbial genome databases for homologs of the S. aureus nitroreductase NtrA yielded several gene products with percentages of sequence identity and similarity that range between 10% and 36%. A dendrogram was constructed based on the alignment of selected amino acid sequences of proteins found to be similar to SA0UHSC_00366 (NfrA), SA0UHSC_00833 (NtrA), SA0UHSC_02258, SA0UHSC_02829, E. coli NfsA, and E. coli NfsB (identity between the selected sequences ranges between 4 and 90%) (Fig. 2). The dendrogram suggests that there are three main groups. The first contains E. coli NfsB, SA0UHSC_02829, and SA0UHSC_02258, with SA0UHSC_02258 being the most distantly related member of this group, and the second includes E. coli NfsA and SA0UHSC_00366 (NfrA). The NtrA protein (SA0UHSC_00833) is located in a third independent group that does not contain any of the E. coli or S. aureus nitroreductases, thus suggesting that S. aureus NtrA is a member of a novel family of nitroreductases. Interestingly, the genome region comparison of the ntrA loci among the nine completely sequenced S. aureus genomes showed that, in all cases, the ntrA gene is flanked upstream by a gene encoding a protein similar to a 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase and downstream by a thioredoxin-encoding gene that is transcribed from the opposite strand.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram of representative nitroreductases families. Organisms and protein sequence gi numbers corresponding to each abbreviation are as follows: ActinobacillusA (152979535) and ActinobacillusB (152979206), Actinobacillus succinogenes; Aeromonas, Aeromonas salmonicida (145298746); Bacillush, Bacillus halodurans (15612866); BacillussA (16080862) and BacillussB (16077850), Bacillus subtilis; Burkholderia, Burkholderia thailandensis (83716954); ChromohalobacterA (92112337) and ChromohalobacterC (92113480); Chromohalobacter salexigens; Corynebacterium, Corynebacterium jeikeium (68536654); Clostridium, Clostridium difficile (126700824); Desulfovibrio, Desulfovibrio desulfuricans G20 (78355133); E. coli NfsA, E. coli K-12 b0851 (16128819); E. coli NfsB, E. coli K-12 b0578 (16128561); Enterococcus, Enterococcus faecalis (29375756); Erythrobacter, Erythrobacter litoraliss (85374565); Erwinia, Erwinia carotovora (50121266); Geobacter, Geobacter uraniumreducens (148263412); Klebsiella, Klebsiella pneumoniae (152969124); Lactococcus, Lactococcus lactis (125623424); ListeriaA (16799400) and ListeriaC (16799563), Listeria innocua; Moorella, Moorella thermoacetica (83590668); Neisseria, Neisseria gonorrhoeae (59800832); Nitrobacter, Nitrobacter winogradskyi (75676226); Pseudomonasp, Pseudomonas putida (148548471); Pseudomonass, Pseudomonas stutzeri (146282796); Psychrobacter, Psychrobacter sp. (148653797); Rubrobacter, Rubrobacter xylanophilus (108804130); SA0U02258, S. aureus SA0UHSC_02258 (88195929); SA0U00366, S. aureus SA0UHSC_00366 (88194164); SA0U02829, S. aureus SA0UHSC_002829 (88196463); SA NtrA, S. aureus SA0UHSC_00833 (88194591); Shigella, Shigella flexneri (24112221); Streptococcuss, Streptococcus sanguinis (125718603); Streptococcust, Streptococcus thermophilus (55821160); Thermosynecoccus, Thermosynechococcus elongatus (22299744); Thiomicrospira, Thiomicrospira crunogena (78484399); VibriocA (15640734) and VibriocB (15601395), Vibrio cholerae; Vibriof, Vibrio fischeri (59713296); Vibriov, Vibrio vulnificus (27366397).

In conclusion, we have shown that S. aureus NtrA is a bifunctional enzyme able to catalyze the reduction of GSNO and nitrofurans. Although the existence of a single protein that combines two activities seems to be a common feature among the GSNO reductases known so far, S. aureus NtrA is the first staphylococci nitroreductase shown to metabolize toxic nitrosothiols.

Even though the presence of NtrA contributes to the activation of nitrofurans, in the absence of these antibiotics NtrA acts as a defense system that allows the decomposition of endogenously formed GSNO, which occurs when S. aureus is exposed to nitrosative stress, thus avoiding the harmful effects caused by transnitrosylation reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was funded by FCT project POCI/SAU-IMI/56088/2004 and by FCT studentships SFRH/BD/22425/2005 (L.S.N.) and SFRH/BD/38457/2007 (A.F.N.T.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 March 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crum-Cianflone, N. F., A. A. Burgi, and B. R. Hale. 2007. Increasing rates of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections among HIV-infected persons. Int. J. STD AIDS 18521-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guay, D. R. 2001. An update on the role of nitrofurans in the management of urinary tract infections. Drugs 61353-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogg, N., R. J. Singh, E. Konorev, J. Joseph, and B. Kalyanaraman. 1997. S-Nitrosoglutathione as a substrate for gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Biochem. J. 323477-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hou, Y., Z. Guo, J. Li, and P. G. Wang. 1996. Seleno compounds and glutathione peroxidase catalyzed decomposition of S-nitrosothiols. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 22888-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansson, E., G. N. Parkinson, W. A. Denny, and S. Neidle. 2003. Studies on the nitroreductase prodrug-activating system. Crystal structures of complexes with the inhibitor dicoumarol and dinitrobenzamide prodrugs and of the enzyme active form. J. Med. Chem. 464009-4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu, L., A. Hausladen, M. Zeng, L. Que, J. Heitman, and J. S. Stamler. 2001. A metabolic enzyme for S-nitrosothiol conserved from bacteria to humans. Nature 410490-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikitovic, D., and A. Holmgren. 1996. S-Nitrosoglutathione is cleaved by the thioredoxin system with liberation of glutathione and redox regulating nitric oxide. J. Biol. Chem. 27119180-19185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson, A. R., P. M. Dunman, and F. C. Fang. 2006. The nitrosative stress response of Staphylococcus aureus is required for resistance to innate immunity. Mol. Microbiol. 61927-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Streker, K., C. Freiberg, H. Labischinski, J. Hacker, and K. Ohlsen. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus NfrA (SA0367) is a flavin mononucleotide-dependent NADPH oxidase involved in oxidative stress response. J. Bacteriol. 1872249-2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trujillo, M., M. N. Alvarez, G. Peluffo, B. A. Freeman, and R. Radi. 1998. Xanthine oxidase-mediated decomposition of S-nitrosothiols. J. Biol. Chem. 2737828-7834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whiteway, J., P. Koziarz, J. Veall, N. Sandhu, P. Kumar, B. Hoecher, and I. B. Lambert. 1998. Oxygen-insensitive nitroreductases: analysis of the roles of nfsA and nfsB in development of resistance to 5-nitrofuran derivatives in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1805529-5539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.