Abstract

Extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli has recently emerged as a major risk factor for community-acquired, travel-related infections in the Calgary Health Region. Molecular characterization was done on isolates associated with infections in returning travelers using isoelectric focusing, PCR, and sequencing for blaCTX-Ms, blaTEMs, blaSHVs, blaOXAs, and plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants. Genetic relatedness was determined with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis using XbaI and multilocus sequence typing (MLST). A total of 105 residents were identified; 6/105 (6%) presented with hospital-acquired infections, 9/105 (9%) with health care-associated community-onset infections, and 90/105 (86%) with community-acquired infections. Seventy-seven of 105 (73%) of the ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were positive for blaCTX-M genes; 55 (58%) produced CTX-M-15, 13 (14%) CTX-M-14, six (6%) CTX-M-24, one (1%) CTX-M-2, one (1%) CTX-M-3, and one (1%) CTX-M-27, while 10 (10%) produced TEM-52, three (3%) TEM-26, 11 (11%) SHV-2, and four (4%) produced SHV-12. Thirty-one (30%) of the ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were positive for aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and one (1%) was positive for qnrS. The majority of the ESBL-producing isolates (n = 95 [90%]) were recovered from urine samples, and 83 (87%) were resistant to ciprofloxacin. The isolation of CTX-M-15 producers belonging to clone ST131 was associated with travel to the Indian subcontinent (India, Pakistan), Africa, the Middle East, and Europe, while clonally unrelated strains of CTX-M-14 and -24 were associated with travel to Asia. Our study suggested that clone ST131 coproducing CTX-M-15, OXA-1, TEM-1, and AAC(6′)-Ib-cr and clonally unrelated CTX-M-14 producers have emerged as important causes of community-acquired, travel-related infections.

Escherichia coli producing CTX-M β-lactamases have become the most prevalent type of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) described during the last 5 years, especially from certain European and South American countries (4). Infections caused by bacteria producing these enzymes are not limited to the hospital setting, and their potential for spread beyond the hospital environment is an important public health concern (27). CTX-M-producing E. coli strains isolated from hospital and community sites often exhibited coresistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, gentamicin, tobramycin, and ciprofloxacin (23). CTX-M enzymes have been associated with the presence of different qnr genes producing proteins named QnrA, QnrS, and QnrB that block the action of fluoroquinolone on bacterial topoisomerases as well as the production of a novel aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme, AAC(6′)-Ib, that has the additional ability to modify certain fluoroquinolones (23).

Multidrug-resistant CTX-M-15-producing E. coli is emerging worldwide in a simultaneous fashion as an important pathogen causing community-onset and hospital-acquired infections (31). An identical clone named ST131 has been identified, using multilocus sequence typing (MLST), among CTX-M-15-producing E. coli isolates isolated from 2000 to 2006 from several countries, including Spain, France, Canada, Portugal, Switzerland, Lebanon, India, Kuwait, and South Korea (7, 22). This clone belongs to the highly virulent phylogenetic group B2 and harbors multidrug-resistant IncFII plasmids. This suggests that clone ST131 has emerged independently in different parts of the world due to ingestion of contaminated food/water sources and/or is being imported into various countries via returning travelers (22). Clone ST131 has also recently been described in the United Kingdom (19), Italy (3), Turkey (34), and the United States (16).

A previous study from the Calgary Health Region has demonstrated that overseas travel is a significant risk factor for acquiring community-acquired infections due to ESBL-producing E. coli (20). This follow-up study was designed to characterize these isolates and to determine if fluoroquinolone resistance in these isolates is partly due to plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants.

(Results of this study were presented at the 49th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Washington, DC, 2008.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

The Calgary Health Region provides all publicly funded health care services to the 1.2 million people residing in the cities of Calgary and Airdrie and numerous adjacent communities covering an area of 37,000 km2. Acute care is provided principally through one pediatric and three large adult hospitals. A centralized laboratory (Calgary Laboratory Services) performs the routine clinical microbiology services for general practitioners, medical specialists, community clinics, and hospitals within the Calgary Health Region. A case of E. coli urinary tract infection was defined as a patient with a clinical suspicion of urinary tract infection (dysuria, urgency, and frequency) whose clean-catch urine yielded more than 105 CFU of this organism per milliliter of urine. A case of travel-associated infection was defined as a patient that had traveled abroad during the past 6 months. Urosepsis was defined as a clinical syndrome of flank pain with tenderness and fever associated with dysuria, urgency, and frequency accompanied by the culture of E. coli from urine, blood, or both.

Bacterial isolates.

All ESBL-producing E. coli isolates recovered from patients between 1 May 2004 and 30 April 2006 with incident travel-related infections were studied. Only nonrepeat isolates from true incident cases were included in this study (20). Hospital-acquired cases were classified as patients that developed infections after 48 h of admission to a health care center. Community-onset cases were classified as those patients that visited community-based collection sites or nursing homes or as those that developed infection within the first 2 days of admission to an acute-care facility. The patients were further classified as having either community-acquired or health care-associated community-onset infections (10). Health care-associated community-onset cases were those that occurred among nursing home residents, hemodialysis patients, or those individuals who were either admitted to a hospital for at least 2 days in the preceding 90 days or received care through a hospital-based clinic in the preceding 30 days.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

MICs to the following drugs were determined by Vitek 2 (Vitek AMS; bioMérieux Vitek Systems Inc., Hazelwood, MO): piperacillin-tazobactam, amoxicillin-clavulanate, imipenem, gentamicin, tobramycin, amikacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, and ciprofloxacin. Throughout this study, results were interpreted using Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria for broth dilution (5). The quality control strains used for this part of the study were E. coli ATCC 25922, E. coli ATCC 35218, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853.

ESBL screening and confirmation testing.

The presence of ESBLs was detected in clinical isolates of E. coli by using the CLSI criteria for ESBL screening and disk confirmation tests (5). Disks for ESBL confirmation tests were obtained from Oxoid Inc. (Nepean, Ontario, Canada). Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603 and E. coli ATCC 25922 were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

β-Lactamase gene identification.

Isoelectric focusing (IEF) which included cefotaxime hydrolysis and inhibitor profiles in polyacrylamide gels was performed on freeze-thaw extracts as previously described (24). PCR amplification of the blaCTX-M, blaOXA, blaTEM, and blaSHV genes was carried out on the isolates with a GeneAmp 9700 ThermoCycler instrument (Applied Biosystems, Norwalk, CT) using PCR conditions and primers as previously described (24, 26). Automated sequencing was performed on the PCR products with the ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Norwalk, CT), using the Sequence Analysis software. The sequences of the different amplicons were compared to each other and to homologous sequences using the Sequence Navigator software. The nucleotide and deduced protein sequences were analyzed using the software available from the Internet at the National Center of Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants.

The amplification of the qnrA, qnrS, and qnrB genes was undertaken with multiplex PCR as described previously (29). aac(6′)-Ib was amplified in a separate PCR using primers and conditions as previously described (28). The variant aac(6′)-Ib-cr was further identified by digestion with BstF5I (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA).

PFGE.

The CTX-M-14- and CTX-M-15-producing E. coli isolates were typed with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) following the extraction of genomic DNA and digestion with XbaI using the standardized E. coli (O157:H7) protocol established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA (15). The subsequent PFGE analyses were performed on a CHEF Mapper apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). DNA relatedness was calculated based on the Dice coefficient, and isolates were considered to be genetically related if the Dice coefficient correlation was 80% or greater, which corresponds to the “possibly related (4 to 6 bands difference)” criteria of Tenover et al. (33).

MLST.

MLST was performed on the CTX-M-15-producing isolates using the seven conserved housekeeping genes (aspC, clpX, fadD, icdA, lysP, mdh, and uidA). A detailed protocol of the MLST procedure, including allelic type and sequence type assignment methods, available at the EcMLST website (http://www.shigatox.net/mlst), was used in this study.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overseas travel as a risk factor for the acquisition of infections due to antimicrobial-resistant organisms is a relatively recent phenomenon (2, 18). It has been described for quinolone-resistant Salmonella spp. (11), quinolone-resistant Shigella spp. (21), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-resistant E. coli (6, 32), SHV-12-producing Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (1), CTX-M-15-producing Shigella sonnei (14), and CTX-M-15-producing E. coli (9).

During the 2 years of prospective surveillance, a total of 105 Calgary Health Region residents, with incident infections associated with travel due to ESBL-producing E. coli isolates, were identified in this study; 6/105 (6%) were hospital-acquired cases, 9/105 (9%) were healthcare-associated community-onset cases, and 90/105 (86%) were classified as community-acquired cases. Of the six E. coli isolates responsible for nosocomial infections, four produced TEM types of ESBLs, and two produced SHV types, while those responsible for health care-associated community-onset infections produced SHV (n = 4) and CTX-M (n = 5) types of ESBLs. Of the 90 E. coli isolates responsible for community-acquired infections, 72 (80%) were positive for blaCTX-M genes, while the remaining 18 produced either TEM (n = 9) or SHV (n = 9) types of ESBLs. All of the patients had symptomatic urinary tract infections, and 15 (14%) presented with the clinical syndrome of urosepsis.

The majority of ESBL-producing isolates (n = 95 [90%]) were recovered from urine, five (5%) from blood, and five (5%) from both blood and urine. Of the 105 isolates included in this study, 65 (62%) were resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 49 (47%) to piperacillin-tazobactam, 78 (74%) to amoxicillin-clavulanate, 53 (50%) to tobramycin, 44 (42%) to gentamicin, one (1%) to amikacin, seven (7%) to nitrofurantoin, and 83 (79%) to ciprofloxacin. No imipenem resistance was detected.

The characteristics of the different ESBLs are illustrated in Table 1. Of the 105 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates associated with travel, 77 (73%) were positive for blaCTX-M genes; 55 (58%) produced CTX-M-15, 13 (14%) produced CTX-M-14, six (6%) produced CTX-M-24, one (1%) produced CTX-M-2, one (1%) produced CTX-M-3, and one (1%) produced CTX-M-27, while 10 (10%) produced TEM-52, three (3%) produced TEM-26, 11 (11%) produced SHV-2, and four (4%) produced SHV-12. Thirty-one (30%) of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates (all producing CTX-M-15) were positive for aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and one (1%) was positive for qnrS. CTX-M-15 was the most common β-lactamase detected in E. coli strains isolated from patients returning from most regions, with the exception of travelers to the United States and Asia (Table 2). However, CTX-M-15 was present in isolates from all areas of travel. CTX-M-14 was the predominant β-lactamase in E. coli isolates recovered from patients returning from Asia.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolates from travelers in the Calgary Health Region

| No. of isolates (n = 105) | pI(s) by IEFa | β-Lactamases | PFGE cloneb (no. of isolates) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45 | 8.9, 7.4, 5.4 | CTX-M-15, OXA-1, TEM-1 | 15A (26), 15AR (5), 15NR (14) |

| 5 | 8.9, 7.4 | CTX-M-15, OXA-1 | 15A (2), 15NR (3) |

| 3 | 8.9, 5.4 | CTX-M-15, TEM-1 | 15NR (3) |

| 2 | 8.9 | CTX-M-15 | 15NR (2) |

| 9 | 8.1 | CTX-M-14 | 14A (3), 14NR (60) |

| 4 | 8.1, 5.4 | CTX-M-14, TEM-1 | 14NR (4) |

| 6 | 8.4 | CTX-M-24 | NA |

| 1 | 8.4 | CTX-M-3 | NA |

| 1 | 8.4, 5.4 | CTX-M-27 | NA |

| 1 | 7.9 | CTX-M-2 | NA |

| 10 | 6.0 | TEM-52 | NA |

| 3 | 5.6 | TEM-26 | NA |

| 11 | 7.6 | SHV-2 | NA |

| 4 | 8.2 | SHV-12 | NA |

IEF with polyacrylamide gels was performed on freeze-thaw extracts.

The 14A isolates formed a cluster with >80% similar PFGE profiles. The 14NR (i.e., not related) isolates were more distantly related. The 15A and 15AR isolates formed a cluster with >80% similar PFGE profiles. The 15AR isolates exhibited a >60% similarity of profiles to the 15A isolates, and this indicates that 15AR is related to 15A. The 15NR (i.e., not related) isolates were more distantly related. NA, not applicable.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of different ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolated from various continents or countries

| Area (no. of isolates) | No. of isolates producing:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-15 | CTX-M-14 | CTX-M-2 | CTX-M-3 | CTX-M-24 | CTX-M-27 | TEM | SHV | |

| United States (31) | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 10 |

| South America (3) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Central America (13) | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Africa (5) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asia (15) | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Middle East (9) | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Europe (12) | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Indian subcontinent (17) | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total (105) | 55 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 13 | 15 |

aThe non-U.S. destinations included South America (Peru and Argentina), Central America (Costa Rica, Mexico, and the Caribbean islands), Africa (Egypt and Kenya), Asia (China, Thailand, Philippines, and Vietnam), the Middle East (Lebanon and Iran), Europe (various countries), and the Indian subcontinent (India and Pakistan).

PFGE identified one closely related group of E. coli isolates producing CTX-M-14 (designated clone 14A; n = 3). The remaining 10 CTX-M-14-producing isolates were not related to clone 14A and were designated 14NR. These clones were previously reported in a molecular epidemiology study (24).

PFGE identified two closely related groups of E. coli isolates producing CTX-M-15 (designated 15A [n = 28] and 15AR [n = 5]). The remaining 22 CTX-M-15-producing isolates were not related to clone 15A or 15AR and were designated 15NR. These clones were previously reported in a molecular epidemiology study (24). MLST performed on the CTX-M-15-producing isolates identified PFGE clones 15A and 15AR as ST131.

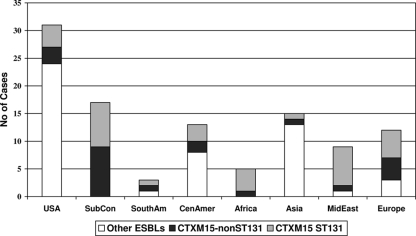

The distribution of different ESBL-producing E. coli isolates isolated from patients that visited various continents or countries is shown in Table 2. The prevalence of CTX-M-15 and MLST clone ST131 among ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from the different continents/countries is illustrated in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Prevalence of CTX-M-15 and MLST clone ST131 among ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolates from different continents/countries. The non-U.S. destinations included South America (SouthAm; Peru and Argentina), Central America (CenAmer; Costa Rica, Mexico, and the Caribbean islands), Africa (Egypt and Kenya), Asia (China, Thailand, Philippines, and Vietnam), the Middle East (MidEast; Lebanon and Iran), Europe (various countries), and the Indian subcontinent (SubCon; India and Pakistan). Other ESBLs include TEM-26 and -52, SHV-2 and -12, and CTX-M-2, -3, -14, -24, and -27.

A previous study from the Calgary Health Region demonstrated that travel to the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East was associated with a high risk of infection with ESBL-producing E. coli in returning travelers. In addition, travel to Asia, Mexico, Central America, and South America was associated with a moderately increased risk of acquisition of infections due to ESBL-producing E. coli (20). However, travel to the United States and Europe was not associated with any significant risk of infection in returning travelers. This study demonstrates that 30/31 (97%) of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from travelers to the Indian subcontinent, Africa, and the Middle East were CTX-M-15 producers and 19/31 (61%) belonged to clone ST131. Twenty-five (81%) of these E. coli isolates were positive for aac(6′)-Ib-cr. This is in comparison with 25/84 (30%) of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from travelers to Asia, Mexico, Central America, South America, Europe, and the United States being CTX-M-15 producers and only 16/84 (19%) belonging to clone ST131. Six (7%) of these isolates were positive for aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and one (1%) was positive for qnrS. These results suggest that E. coli clone ST131 producing CTX-M-15 with aac(6′)-Ib-cr contributes to the worldwide spread of CTX-M-producing E. coli most likely via colonizing and infecting travelers returning from high-risk areas such as the Indian subcontinent, Africa, and the Middle East. Our study confirms the findings of two previous studies that recently postulated that the sudden simultaneous appearance of E. coli clone ST131 producing CTX-M-15 in several countries spanning three continents was likely due to foreign travel (7, 22).

A recent case series from New Zealand describes patients with community-onset genitourinary tract infections due to CTX-M-15-producing E. coli who had a history of travel to or recent emigration from the Indian subcontinent (9). Seventeen patients with symptomatic urinary tract infections in our study had visited the Indian subcontinent during the past 6 months, and five presented with urosepsis. One infection was classified as health care-associated community-onset infection, and the remaining 16 were community-acquired infections. All of the E. coli isolates produced CTX-M-15, OXA-1, and TEM-1, eight belonged to clone ST131, and six produced AAC(6′)-Ib-cr. CTX-M-15-producing E. coli was first described in India (17), and recent surveys of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from India identified CTX-M-15 in 73% of hospital isolates (8). This was supported by other reports from India (12, 30). It is therefore possible that the travelers visiting the Indian subcontinent could acquire CTX-M-15-producing E. coli without necessarily being in contact with the health care system in that country.

Travelers who had visited India, South America, Africa, the Middle East, and Europe presented with urinary tract infections most often caused by CTX-M-15-producing E. coli (Table 2). This was different for travelers with urinary tract infections returning from the United States and Asia (China, Thailand, Philippines, and Vietnam). Only 2/15 E. coli isolates isolated from travelers that visited Asia produced CTX-M-15, as opposed to 8/15 (57%) that produced CTX-M-14 (P = 0.037) (Table 2). A recent review indicated that CTX-M-14 is the most common ESBL identified from E. coli clinical isolates in Asia (especially in China) (13) and supports the notion that returning travelers acquired the most predominant ESBL in the country visited. Of interest was the fact that the CTX-M-14-producing E. coli isolates from returning travelers from China and Vietnam were not clonally related compared to those CTX-M-14 producers isolated from travelers to the United States (n = 3) that belonged to PFGE clonal group 14A. This clone had previously been described in the Calgary Health Region as causing community-wide, common-source types of outbreaks during 2000 and 2001 in older females with community-acquired urinary tract infections (25).

Our study illustrated that E. coli clone ST131 coproducing CTX-M-15, OXA-1, TEM-1, and AAC(6′)-Ib-cr has emerged in our region as an important cause of community-acquired, travel-related infections, especially for destinations such as the Indian subcontinent, Africa, and the Middle East, while clonally unrelated CTX-M-14 producers were associated with travel to Asia. Additionally, we have shown a high prevalence of aac(6′)-Ib-cr in ST131 strains originating primarily from the Indian subcontinent, Africa, and the Middle East. Empirical therapies for patients with urinary tract infections or urosepsis after travel to these areas need to be adjusted accordingly to include treatment options for ESBL-producing isolates.

A limitation of this study is that we could not rule out the possibility that the association with overseas travel and infections due to ESBL-producing E. coli was real. This was due to the design of the study, which did not include a control group. Therefore, it is possible that this could reflect, at least in part, the current ESBL scenario in Calgary.

In summary, this study highlights the fact that there is a serious need to monitor the spread of multidrug-resistant E. coli clone ST131 throughout the world. In addition, the role of overseas travel as a potential risk factor for acquiring antimicrobial-resistant organisms needs to be further investigated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Calgary Laboratory Services (no. 73-4063).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 April 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al Naiemi, N., B. Zwart, M. C. Rijnsburger, R. Roosendaal, Y. J. Debets-Ossenkopp, J. A. Mulder, C. A. Fijen, W. Maten, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, and P. H. Savelkoul. 2008. Extended-spectrum-β-lactamase production in a Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi strain from the Philippines. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2794-2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batchelor, M., K. Hopkins, E. J. Threlfall, F. A. Clifton-Hadley, A. D. Stallwood, R. H. Davies, and E. Liebana. 2005. blaCTX-M genes in clinical Salmonella isolates recovered from humans in England and Wales from 1992 to 2003. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1319-1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cagnacci, S., L. Gualco, E. Debbia, G. C. Schito, and A. Marchese. 2008. European emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli clonal groups O25:H4-ST 131 and O15:K52:H1 causing community-acquired uncomplicated cystitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2605-2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantón, R., and T. M. Coque. 2006. The CTX-M β-lactamase pandemic. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:466-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 18th informational supplement. M100-S18. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 6.Colgan, R., J. R. Johnson, M. Kuskowski, and K. Gupta. 2008. Risk factors for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance in patients with acute uncomplicated cystitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:846-851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coque, T. M., A. Novais, A. Carattoli, L. Poirel, J. Pitout, L. Peixe, F. Baquero, R. Canton, and P. Nordmann. 2008. Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:195-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ensor, V. M., M. Shahid, J. T. Evans, and P. M. Hawkey. 2006. Occurrence, prevalence and genetic environment of CTX-M beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae from Indian hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:1260-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman, J. T., S. J. McBride, H. Heffernan, T. Bathgate, C. Pope, and R. B. Ellis-Pegler. 2008. Community-onset genitourinary tract infection due to CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli among travelers to the Indian subcontinent in New Zealand. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47:689-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman, N. D., K. S. Kaye, J. E. Stout, S. A. McGarry, S. L. Trivette, J. P. Briggs, W. Lamm, C. Clark, J. MacFarquhar, A. L. Walton, L. B. Reller, and D. J. Sexton. 2002. Health care-associated bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann. Intern. Med. 137:791-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta, S. K., F. Medalla, M. W. Omondi, J. M. Whichard, P. I. Fields, P. Gerner-Smidt, N. J. Patel, K. L. Cooper, T. M. Chiller, and E. D. Mintz. 2008. Laboratory-based surveillance of paratyphoid fever in the United States: travel and antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:1656-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta, V., and P. Datta. 2007. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) in community isolates from North India: frequency and predisposing factors. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 11:88-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkey, P. M. 2008. Prevalence and clonality of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Asia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14(Suppl. 1):159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hrabák, J., J. Empel, M. Gniadkowski, Z. Halbhuber, K. Rebl, and P. Urbaskova. 2008. CTX-M-15-producing Shigella sonnei strain from a Czech patient who traveled in Asia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2147-2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter, S. B., P. Vauterin, M. A. Lambert-Fair, M. S. Van Duyne, K. Kubota, L. Graves, D. Wrigley, T. Barrett, and E. Ribot. 2005. Establishment of a universal size standard strain for use with the PulseNet standardized pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols: converting the national databases to the new size standard. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1045-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson, J. R., B. D. Johnston, J. H. Jorgensen, J. Lewis II, A. Robicsek, M. Menard, C. Clabots, S. J. Weissman, N. D. Hanson, R. Owens, K. Lolans, and J. Quinn. 2008. CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli (Ec) in the United States (US): predominance of sequence type ST131 (O25:H4). Abstr. 48th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. Washington, DC.

- 17.Karim, A., L. Poirel, S. Nagarajan, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (CTX-M-3 like) from India and gene association with insertion sequence ISEcp1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 201:237-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, S., J. Hu, R. Gautom, J. Kim, B. Lee, and D. S. Boyle. 2007. CTX-M extended-spectrum beta-lactamases, Washington State. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:513-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau, S. H., M. E. Kaufmann, D. M. Livermore, N. Woodford, G. A. Willshaw, T. Cheasty, K. Stamper, S. Reddy, J. Cheesbrough, F. J. Bolton, A. J. Fox, and M. Upton. 2008. UK epidemic Escherichia coli strains A-E, with CTX-M-15 beta-lactamase, all belong to the international O25:H4-ST131 clone. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1241-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laupland, K. B., D. L. Church, J. Vidakovich, M. Mucenski, and J. D. Pitout. 2008. Community-onset extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli: importance of international travel. J. Infect. 57:441-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mensa, L., F. Marco, J. Vila, J. Gascon, and J. Ruiz. 2008. Quinolone resistance among Shigella spp. isolated from travellers returning from India. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:279-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolas-Chanoine, M. H., J. Blanco, V. Leflon-Guibout, R. Demarty, M. P. Alonso, M. M. Canica, Y. J. Park, J. P. Lavigne, J. Pitout, and J. R. Johnson. 2008. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:273-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitout, J. D. 2008. Multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae: new threat of an old problem. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 6:657-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitout, J. D., D. L. Church, D. B. Gregson, B. L. Chow, M. McCracken, M. R. Mulvey, and K. B. Laupland. 2007. Molecular epidemiology of CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli in the Calgary Health Region: emergence of CTX-M-15-producing isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1281-1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitout, J. D., D. B. Gregson, D. L. Church, S. Elsayed, and K. B. Laupland. 2005. Community-wide outbreaks of clonally related CTX-M-14 β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli strains in the Calgary health region. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2844-2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitout, J. D., N. Hamilton, D. L. Church, P. Nordmann, and L. Poirel. 2007. Development and clinical validation of a molecular diagnostic assay to detect CTX-M-type beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:291-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitout, J. D., and K. B. Laupland. 2008. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8:159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitout, J. D., Y. Wei, D. L. Church, and D. B. Gregson. 2008. Surveillance for plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants in Enterobacteriaceae within the Calgary Health Region, Canada: the emergence of aac(6′)-Ib-cr. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:999-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robicsek, A., J. Strahilevitz, D. F. Sahm, G. A. Jacoby, and D. C. Hooper. 2006. qnr prevalence in ceftazidime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2872-2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodrigues, C., U. Shukla, S. Jog, and A. Mehta. 2005. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing flora in healthy persons. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:981-982. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossolini, G. M., M. M. D'Andrea, and C. Mugnaioli. 2008. The spread of CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14(Suppl. 1):33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sannes, M. R., E. A. Belongia, B. Kieke, K. Smith, A. Kieke, M. Vandermause, J. Bender, C. Clabots, P. Winokur, and J. R. Johnson. 2008. Predictors of antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli in the feces of vegetarians and newly hospitalized adults in Minnesota and Wisconsin. J. Infect. Dis. 197:430-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yumuk, Z., G. Afacan, M. H. Nicolas-Chanoine, A. Sotto, and J. P. Lavigne. 2008. Turkey: a further country concerned by community-acquired Escherichia coli clone O25-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:284-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]