Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates frequently contain complex mixtures of blaSHV alleles. A high-resolution melting-based method for interrogating the extended-spectrum activity conferring codon 238 and 240 polymorphisms was developed. This detects minority extended-spectrum β-lactamase-encoding alleles, allows estimation of allele ratios, and discriminates between single and double mutants.

High-resolution melting (HRM) analysis is showing considerable promise as a method for rapid and cost-effective interrogation of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (5). There have been numerous reports of the successful use of HRM to discriminate homozygotes and heterozygotes in humans (5). However, the use of HRM to analyze allele mixtures that are not 1:1 and to reveal the presence of minority alleles has been little explored.

The increasing prevalence of bacteria producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) has become a significant problem facing health care across the world. Many ESBLs are derived from plasmid-encoded SHV or TEM β-lactamases (12-14). The conversion of a non-ESBL SHV enzyme into an ESBL is nearly always associated with a G238S (GGC→AGC) substitution (numbering according to that of Ambler et al. [1]), while a further extension of the spectrum of activity is mediated by an E240K (GAG→AAG) substitution (12). Although there are many other substitutions reported, mutations of codons 238 and 240 are by far the most significant for ESBL activity of the blaSHV family (http://www.lahey.org/Studies/).

An unusual aspect of the biology of the SHV-encoding gene, blaSHV, is that it is present on the chromosome of most Klebsiella pneumoniae strains (2, 3). However, it is also disseminated on plasmids, and most SHV ESBLs are plasmid encoded. It appears that there have been two recent mobilizations of non-ESBL blaSHV from the K. pneumoniae chromosome onto plasmids, the mobilized genes being blaSHV-1 and blaSHV-11, which differ only at codon 35 (7). The G238S mutant-encoding derivatives of these are blaSHV-2 and blaSHV-2a, respectively, while the G238S and E240K double-mutant-encoding derivatives are blaSHV-5 and blaSHV-12, respectively. These six blaSHV variants are all abundant.

The existence of both chromosome and plasmid-borne blaSHV means that many K. pneumoniae strains harbor mixtures of blaSHV alleles, and the ratios between alleles can vary widely (6, 8, 9). It has also been determined that the presence of a minority ESBL-encoding allele confers an ESBL-positive phenotype (9). This provides a diagnostic challenge.

An allele-specific real-time PCR (sometimes known as kinetic PCR) method for interrogating the blaSHV codon 238 and 240 SNPs has previously been reported (8, 9). This has proven effective, but it requires four separate PCRs. Also, it is difficult to calibrate for interlab comparison because of the effects of small batch-to-batch variations in primer concentration and quality (unpublished data). In contrast, the allele discrimination in an HRM-based assay takes place at the end of the PCR, so the format is inherently more robust.

Here, we demonstrate a single-tube HRM-based assay for codon 238 and 240 mutations in the blaSHV gene and its comparison with allele-specific real-time PCR. To support this assay, data analysis methods were developed for the inference of confidence limits regarding whether or not an analyte contains a mutant allele. This procedure is similar in some respects to the probe-based melting analyses of Chia et al. and Randegger and Hachler (4, 15), but it is inherently simpler and provides more information.

Two isolate collections of K. pneumoniae were used in this study (Table 1). Isolates A1 to L1 are clinical isolates from the Princess Alexandra Hospital (PAH) in Brisbane, Australia, have previously been characterized, and contain various mixtures of blaSHV-11, blaSHV-2a, and blaSHV-12 (8, 9, 11, 16). Isolates 14 to 121 are derived from the SENTRY collection (10). All strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and stored in cryovials with 12% glycerol at −80°C. The isolates that are asterisked in Table 1 are derivatives of the clinical isolates that have been subjected to selection for resistance to 128 μg/ml cefotaxime (8).

TABLE 1.

blaSHV allele distributions and results from allele-specific real-time PCR and HRM assays

| Origin and isolate | ESBL phenotype | % blaSHV alleles

|

Kinetic PCRΔCTb

|

WT or single- or double-mutant strain | Difference in graph amplitude | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 238 mutation | 240 mutation | Codon 238 | Codon 240 | Combined | ||||

| PAH | |||||||||

| B2 | Negative | 100 | 0 | 0 | 4.97 | 10.07 | 15.04 | WTc | 3.27 |

| K2 | Negative | 100 | 0 | 0 | 5.38 | 5.86 | 11.24 | WTc | 2.52 |

| J3 | Negative | 100 | 0 | 0 | 5.22 | 7.02 | 12.24 | WTc | 1.97 |

| A1 | Positive | 50 | 50 | 0 | −0.32 | 6.60 | 6.28 | Singlec | −10.79 |

| D1 | Positive | 25 | 75 | 10 | −1.19 | 6.26 | 5.07 | Singlec | −12.96 |

| J2 | Positive | 80 | 20 | 20 | 1.07 | 1.36 | 2.43 | Doublec | −10.29 |

| L1 | Positive | 60 | 40 | 35 | −0.27 | −0.11 | −0.38 | Doublec | −17.40 |

| I1 | Positive | 10 | 90 | 65 | −1.85 | −3.01 | −4.86 | Doublec | −25.91 |

| B1 | Positive | −1.10 | 6.71 | 5.61 | Singled | −12.07 | |||

| F1 | Positive | −1.18 | 7.36 | 6.18 | Singled | −12.19 | |||

| B1a | Positive | −1.94 | 6.98 | 5.04 | Singled | −16.16 | |||

| F1a | Positive | −1.92 | 7.93 | 5.01 | Singled | −14.92 | |||

| SENTRY | |||||||||

| 30 | Negative | 5.39 | 6.35 | 11.74 | WTd | 1.10 | |||

| 54 | Negative | 4.91 | 5.96 | 10.87 | WTd | 0.13 | |||

| 70 | Negative | 5.24 | 6.18 | 11.42 | WTd | −0.24 | |||

| 85 | Negative | 3.73 | 9.68 | 13.41 | WTd | −1.03 | |||

| 102 | Negative | 4.71 | 11.00 | 15.71 | WTd | 0.13 | |||

| 104 | Negative | 4.13 | 7.35 | 11.48 | WTd | 1.46 | |||

| 105 | Negative | 4.10 | 7.43 | 11.53 | WTd | −1.01 | |||

| 106 | Negative | 3.90 | 11.80 | 15.70 | WTd | 0.40 | |||

| 107 | Negative | 3.45 | 10.65 | 14.10 | WTd | −0.11 | |||

| 108 | Negative | 3.40 | 7.75 | 11.15 | WTd | −2.19 | |||

| 109 | Negative | 3.69 | 10.23 | 13.92 | WTd | 0.95 | |||

| 110 | Negative | 4.91 | 7.04 | 11.95 | WTd | −0.24 | |||

| 113 | Negative | 4.17 | 12.72 | 16.89 | WTd | −0.73 | |||

| 114 | Negative | 3.92 | 12.79 | 16.71 | WTd | −1.87 | |||

| 115 | Negative | 3.35 | 10.93 | 14.28 | WTd | −2.23 | |||

| 116 | Negative | 4.88 | 12.79 | 17.67 | WTd | −1.44 | |||

| 120 | Negative | 4.67 | 7.07 | 11.74 | WTd | −0.22 | |||

| 121 | Negative | 5.30 | 6.82 | 11.58 | WTd | −0.51 | |||

| 14 | Positive | 0.74 | 0.24 | 0.98 | Doubled | −15.28 | |||

| 18 | Positive | −0.92 | −4.50 | −5.42 | Doubled | −24.88 | |||

| 58 | Positive | 0.51 | 4.83 | 5.34 | Singled | −16.40 | |||

| 54a | Positive | 0.16 | 6.77 | 6.93 | Singled | −9.02 | |||

| 110a | Positive | −1.85 | 7.61 | 5.76 | Singled | −13.13 | |||

| 120a | Positive | 1.98 | 7.00 | 8.98 | Singled | −4.86 | |||

| 121a | Positive | 2.06 | 6.89 | 8.95 | Singled | −4.34 | |||

Isolates that were subjected to stepwise selection for resistance to increasing cefotaxime concentrations and are resistant to 128 μg/ml cefotaxime.

Shown are the mean ΔCT measurements from three separate experiments.

Allele content was directly demonstrated by analysis of cloned PCR products.

Allele content was deduced on the basis of consistency between the allele-specific real-time PCR, HRM data, and ESBL phenotype.

DNA was extracted, using a DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen), from 2.5-ml cultures grown overnight in LB broth. The resuspended DNA was stored at −20°C. All reactions for both the allele-specific real-time PCR assay and HRM assay were performed in a Rotor-Gene 6000 real-time PCR device (Qiagen).

Allele-specific PCR was carried out essentially as previously described by Hammond et al. (9). The reactions were performed in 10-μl volumes, containing SensiMix NoRef master mix at a 1× concentration (Quantace), Sybr green I at a 1× concentration, 5 pmol of common primer (Shv238reverse [5′-CGGCGTATCCCGCAGATAA-3′] or Shv240reverse [5′-CCGGCGGGCTGGTTTAT-3′]), 5pmol of either the wild-type (WT)-specific primer (Shv238wt [5′-CGCCGATAAGACCGGAGCTG-3′] or Shv240wt [5′-GCGCGCACCCCGCTC-3′]) or mutant-specific primer (Shv238mt [5′-CGCCGATAAGACCGGAGCTA-3′] or Shv240mt [5′-GCGCGCACCCCGCTT-3′]), and 50 ng of DNA template. Thermocycling parameters were as described by Hammond et al. (9). The ΔCT values were calculated by subtracting the CT for the WT-specific reaction from the CT for the mutant-specific reaction. It has previously been shown by Hammond and coworkers that ESBL-negative isolates have codon 238 ΔCT values of >2.5 and codon 240 ΔCT values of >5 (8), and these are the cutoffs used for presumptive mutant allele detection by allele-specific real-time PCR.

The HRM assay was carried out using primers SHVmutHRM_F (5′-CGCCGATAAGACCGGAGCT-3′) and SHVmutHRM_R (5′-CCGCGCGCACCCCGCT-3′). These were designed to anneal very close to the SNPs, and the amplified fragment was only 39 bp. The small size of this fragment maximizes the differences in melting temperature (Tm) conferred by the SNPs and allows for short cycling times. PCR was performed in a 10-μl reaction, containing SensiMix NoRef master mix at a 1× concentration (Quantace), Sybr green I at 1× concentration, 5 pmol of each primer, Q-solution at a 1× concentration (Qiagen), and 1 ng of DNA template. Thermocycling parameters were as follows: 50°C for 2 min; 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 65°C for 5 s, and 72°C for 10 s; 95°C for 2 min; and 50°C for 30s. The amplification was followed by HRM from 70 to 86°C at 0.05°C increments, remaining at each step for 2 s. In order to calculate confidence limits for conclusions regarding the sequence of the amplified fragment, the numerical data defining the normalized HRM curves were exported using the “export” function of the software supplied with the Corbett 6000 device, and the mean and standard deviation (SD) were defined at each temperature of the melting protocol. From this, the 95% confidence limits were calculated as the mean ± 1.96 × SD. These numbers were used to define a 95% confidence limit area on the difference graph that is obtained by setting the mean of all of the WT HRM data as the baseline. The amplitudes at the nadirs of the HRM difference graphs were calculated with reference to the mean for all WT isolates.

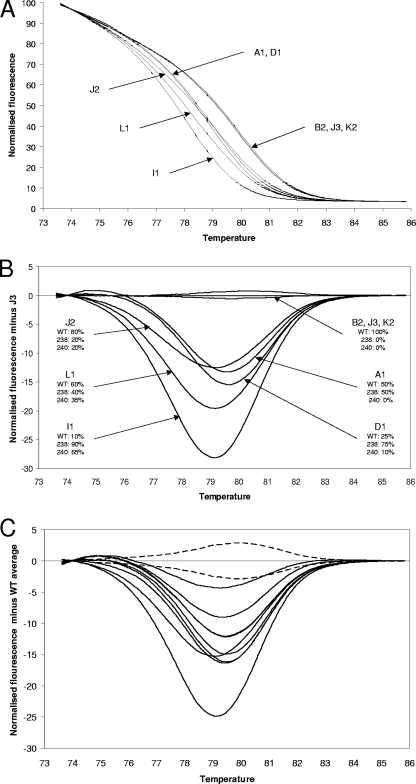

The fully characterized samples for the development of this assay were K. pneumoniae clinical isolates with blaSHV allele ratios that had previously been determined by allele-specific real-time PCR and also by the cloning and analysis of PCR products (5, 10). These were subjected to HRM analysis, and in addition, the allele-specific real-time PCR assays were repeated so as to control for the effect on primer extension efficiency of different primer batches (Table 1 and Fig. 1A and B). The ESBL-positive isolates were clearly discriminated from the ESBL-negative isolates, with the mutant samples having lower Tm values, consistent with the G→A substitutions. The ESBL-positive isolates included J2, which has 80% WT alleles and 20% double-mutant (blaSHV-12) alleles. This yielded a very different HRM curve from the WT isolates. Therefore, this method can detect mutant alleles when they in the minority. The clear identification of a minority allele probably reflects the formation of heteroduplexes which depress the Tm. In the difference graph (Fig. 1B), it can be seen that the double-mutant (blaSHV-12)-containing isolates J2, L1, and I1 can be easily discriminated by eye because the curve nadirs are displaced to the left. However, isolate D1, which contains just 10% double-mutant (blaSHV-12) alleles and a high proportion of single-mutant (blaSHV-2a) alleles, was not discriminated from A1, in which only the WT and single-mutant alleles have been detected. In addition, there was correlation between the difference graph amplitudes and the ratio between the WT and mutant alleles. Because the difference graph amplitudes are derived from melt curves that are always normalized to the same number of arbitrary fluorescence units by the Corbett 6000 software, they can be compared between runs.

FIG. 1.

HRM data. (A) Normalized HRM graphs from the PAH isolates. Isolates containing mutated alleles (A1, D1, J2, L1, and I1) are clearly separated from isolates containing only WT alleles (B2, J3, and K2). (B) Difference graph from the PAH isolates, with the fluorescence of isolate J3 set as the baseline. For each isolate, the number and allelic distribution are stated. (C) Difference graph of the additional 27 SENTRY isolates (18 WT, 7 single mutant, 2 double mutant) isolates. The baseline used was the average fluorescence data of 21 WT (ESBL negative) isolates. The area representing the 95% confidence limit for the WT sequence is delineated with dotted lines. All ESBL-positive isolates yielded difference graph curves outside the 95% confidence limit area. The two curves with nadirs displaced to the left are the two double-mutant isolates, 14 and 18.

To further test this method, 27 diverse K. pneumoniae isolates (18 WT, 7 single mutants, and 2 double mutants), from the Asia-Pacific component of the SENTRY program (10) were subject to analysis. All were analyzed by HRM and allele-specific real-time PCR (Table 1 and Fig. 1C). Some of these isolates had been subjected to allele-specific real-time PCR previously (8, 9), but all isolates were subjected to this procedure during the course of this study. Once again, the ESBL-positive isolates were discriminated from the ESBL-negative isolates, and isolates with two mutations were discriminated from those with one mutation on the basis of displacement of the nadir of the difference graph to the left. The greater number of samples enabled the power of the HRM assay to indicate allele ratios to be examined more rigorously. The correlation coefficient for the linear regression of the combined kinetic PCR ΔCT values versus the amplitude at the nadirs of the HRM difference graphs for the “single-mutant” ESBL-positive isolates is 0.94 (P < 0.0001). The value for “double-mutant” isolates is 0.98 (P = 0.0023). This confirms that this assay can provide an indication of allele ratios. The data from the 18 SENTRY WT isolates together with the 3 PAH WT isolates (B2, J3, and K2) were used to obtain 95% confidence limits for the HRM curve corresponding to the WT allele. This not only indicates when the presence of a mutation should be called but also facilitates the portability of this method. The Tm of the WT sequence using our Rotor-Gene 6000 device is 79.00 ± 0.15°C. It is our experience that an individual Corbett 6000 device is highly accurate with respect to relative temperatures during runs, but absolute temperature calibration between different Corbett 6000 devices can differ by up to 0.5°C. The 95% confidence limit curves for the WT sequence can easily be adjusted with reference to a Tm determined from a small number of runs of the procedure against a WT sequence on a particular machine.

In conclusion, an HRM-based method for interrogating the clinically significant codon 238 and codon 240 SNPs of the blaSHV gene has been developed. The method requires no probes, makes use of a low-cost Sybr green-based master mix, detects mutant alleles if they are in the minority, and provides an indication of the allele ratio. The method costs <$0.60 per sample in materials, even when carried out in duplicate, and takes approximately 1 h.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by project grant 390121 from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

We thank John Turnidge and the SENTRY program for the SENTRY isolates and Graeme Nimmo and Queensland Health Pathology Service for the PAH isolates.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 April 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler, R. P., A. F. Coulson, J. M. Frere, J. M. Ghuysen, B. Joris, M. Forsman, R. C. Levesque, G. Tiraby, and S. G. Waley. 1991. A standard numbering scheme for the class A beta-lactamases. Biochem. J. 276:269-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babini, G. S., and D. M. Livermore. 2000. Are SHV β-lactamases universal in Klebsiella pneumoniae? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2230. (Letter.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaves, J., M. G. Ladona, C. Segura, A. Coira, R. Reig, and C. Ampurdanés. 2001. SHV-1 β-lactamase is mainly a chromosomally encoded species-specific enzyme in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2856-2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chia, J.-H., C. Chu, L.-H. Su, C.-H. Chiu, A.-J. Kuo, C.-F. Sun, and T.-L. Wu. 2005. Development of a multiplex PCR and SHV melting-curve mutation detection system for detection of some SHV and CTX-M β-lactamases of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter cloacae in Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4486-4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erali, M., K. V. Voelkerding, and C. T. Wittwer. 2008. High resolution melting applications for clinical laboratory medicine. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 85:50-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Essack, S. Y., L. M. C. Hall, D. G. Pillay, M. L. McFadyen, and D. M. Livermore. 2001. Complexity and diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains with extended-spectrum β-lactamases isolated in 1994 and 1996 at a teaching hospital in Durban, South Africa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:88-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford, P. J., and M. B. Avison. 2004. Evolutionary mapping of the SHV beta-lactamase and evidence for two separate IS26-dependent blaSHV mobilization events from the Klebsiella pneumoniae chromosome. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond, D. S., T. Harris, J. Bell, J. Turnidge, and P. M. Giffard. 2008. Selection of SHV extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-dependent cefotaxime and ceftazidime resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae requires a plasmid-borne blaSHV gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:441-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond, D. S., J. M. Schooneveldt, G. R. Nimmo, F. Huygens, and P. M. Giffard. 2005. blaSHV genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae: different allele distributions are associated with different promoters within individual isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:256-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirakata, Y., J. Matsuda, Y. Miyazaki, S. Kamihira, S. Kawakami, Y. Miyazawa, Y. Ono, N. Nakazaki, Y. Hirata, M. Inoue, J. D. Turnidge, J. M. Bell, R. N. Jones, and S. Kohno. 2005. Regional variation in the prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing clinical isolates in the Asia-Pacific region (SENTRY 1998-2002). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 52:323-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard, C., A. van Daal, G. Kelly, J. Schooneveldt, G. Nimmo, and P. M. Giffard. 2002. Identification and minisequencing-based discrimination of SHV β-lactamases in nosocomial infection-associated Klebsiella pneumoniae in Brisbane, Australia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:659-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacoby, G. A. 1994. Genetics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13(Suppl. 1):S2-S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu, P. Y.-F., J.-C. Tung, S.-C. Ke, and S.-L. Chen. 1998. Molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in a district hospital in Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2759-2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philippon, A., G. Arlet, and P. H. Lagrange. 1994. Origin and impact of plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13(Suppl. 1):S17-S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Randegger, C. C., and H. Hachler. 2001. Real-time PCR and melting curve analysis for reliable and rapid detection of SHV extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1730-1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schooneveldt, J. M., G. R. Nimmo, and P. Giffard. 1998. Detection and characterisation of extended spectrum beta-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae causing nosocomial infection. Pathology 30:164-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]