Abstract

The overproduction of chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase poses a serious challenge to the successful treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections with β-lactam antibiotics. The induction of ampC expression by β-lactams is mediated by the disruption of peptidoglycan (PG) recycling and the accumulation of cytosolic 1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramyl peptides, catabolites of PG recycling that are generated by an N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase encoded by nagZ (PA3005). In the absence of β-lactams, ampC expression is repressed by three AmpD amidases encoded by ampD, ampDh2, and ampDh3, which act to degrade these 1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramyl peptide inducer molecules. The inactivation of ampD genes results in the stepwise upregulation of ampC expression and clinical resistance to antipseudomonal β-lactams due to the accumulation of the ampC inducer anhydromuropeptides. To examine the role of NagZ on AmpC-mediated β-lactam resistance in P. aeruginosa, we inactivated nagZ in P. aeruginosa PAO1 and in an isogenic triple ampD null mutant. We show that the inactivation of nagZ represses both the intrinsic β-lactam resistance (up to 4-fold) and the high antipseudomonal β-lactam resistance (up to 16-fold) that is associated with the loss of AmpD activity. We also demonstrate that AmpC-mediated resistance to antipseudomonal β-lactams can be attenuated in PAO1 and in a series of ampD null mutants using a selective small-molecule inhibitor of NagZ. Our results suggest that the blockage of NagZ activity could provide a strategy to enhance the efficacies of β-lactams against P. aeruginosa and other gram-negative organisms that encode inducible chromosomal ampC and to counteract the hyperinduction of ampC that occurs from the selection of ampD null mutations during β-lactam therapy.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a versatile gram-negative bacterium that is ubiquitous in the environment. Over the last century, it has emerged as one of the most significant opportunistic pathogens of humans and now accounts for over 10% of all hospital-acquired infections (10, 35, 41). P. aeruginosa exhibits high levels of intrinsic resistance to antibiotics, and P. aeruginosa infections are often persistent and associated with considerable morbidity and mortality (12, 36). P. aeruginosa is a leading cause of nosocomial pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and secondary bacteremia associated with burn wounds (36, 46). Moreover, environmental reservoirs of P. aeruginosa play a primary role in the morbidity and mortality of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) by chronically colonizing the lungs of these patients (35). Nearly 80% of patients with CF become infected with this microbe by early adulthood (9, 13, 23).

Many antibiotics initially overcome the intrinsic drug resistance mechanisms of P. aeruginosa; however, all clinically relevant therapies can be compromised by the generation of drug-resistant genetic mutants (28). Intrinsic resistance to β-lactam antibiotics occurs via the induction of chromosomally encoded AmpC β-lactamase (19, 29). The degree of resistance to β-lactams depends on the level of ampC gene induction; although they are susceptible to hydrolysis by AmpC, some penicillins (such as piperacillin) and cephalosporins (such as cefepime or ceftazidime) exhibit antipseudomonal activity because they are weak inducers of ampC expression (27). However, the prolonged use of antipseudomonal β-lactams frequently selects for mutants that hyperproduce AmpC β-lactamase, which often leads to the failure of treatment with these antibiotics (11, 28).

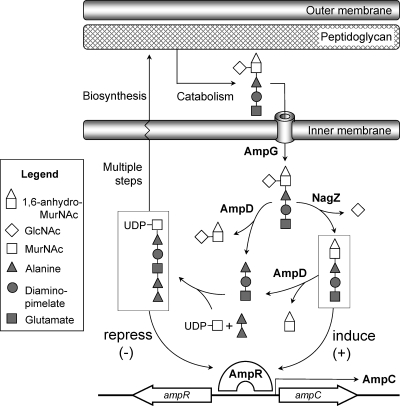

Inducible chromosomal ampC has been identified in a number of enterobacteria and in P. aeruginosa. The regulation of ampC induction in these microorganisms is closely coupled to cell wall peptidoglycan (PG) recycling (Fig. 1) (27, 32, 33). During growth, periplasmic autolysins process a considerable amount of PG into GlcNAc-1,6-anhydromuropeptide (tri-, tetra-, and pentapeptide) fragments (for a review, see reference 49). These fragments are transported into the cytosol (4, 6), where the nonreducing GlcNAc residue is removed by a family 3 (14) glycoside hydrolase encoded by nagZ (3, 50). The resulting products are GlcNAc and a pool of cytosolic 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc peptides (tri-, tetra-, and pentapeptides) (3, 50), which are normally recycled into UDP-MurNAc pentapeptide, a PG precursor that is exported to the periplasm and reincorporated back into the cell wall.

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the PG recycling pathway and its role in AmpC β-lactamase induction. During growth, GlcNAc-1,6-anhydro-MurNAc tri-, tetra-, and pentapeptides (only the tripeptide species is shown) are excised from the PG and transported into the cytoplasm via the AmpG permease. The removal of GlcNAc by NagZ produces 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc peptide (boxed at the right), and either the tri- or pentapeptide species is believed to be responsible for the activation of AmpR to express ampC from the ampC-ampR operon. AmpD clears the muropeptide from the cytoplasm by removing the stem peptides from both GlcNAc-1,6-anhydro-MurNAc and 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc. These PG degradation products are eventually recycled into UDP-MurNAc pentapeptide (boxed at the left), a precursor molecule of PG synthesis and a repressor of AmpR. Exposure to β-lactams causes an increased cytosolic concentration of the 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc peptide that is sufficient to convert AmpR into an activator of ampC transcription.

From the pool of 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc peptide catabolites, either the tripeptide species (17) or the pentapeptide species (7) is believed to be the signaling molecule that induces ampC transcription, whereas the anabolic product UDP-MurNAc pentapeptide acts to repress ampC transcription (Fig. 1). These metabolites are thought to competitively regulate ampC transcription by directly binding to a LysR-type transcriptional regulator encoded by ampR (17). Together, ampR and ampC form a divergent operon with overlapping promoter regions to which AmpR binds and thereby regulates the transcription of both genes (2, 26). The relative levels of these metabolites govern whether ampC is transcribed.

Under normal growth conditions, the cytosolic concentration of 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc peptide is suppressed by the activity of AmpD, a cytoplasmic N-acetyl-muramyl-l-alanine amidase that cleaves the stem peptide off from both GlcNAc-1,6-anhydro-MurNAc peptide and 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc peptide (16, 18). The low cellular level of these inducer molecules therefore allows UDP-MurNAc pentapeptide to bind to AmpR and promote the formation of an AmpR-DNA complex that represses ampC transcription. Exposure to β-lactams, however, elevates the level of PG fragmentation (6, 34, 48) to levels that cannot be efficiently processed by endogenous AmpD activities, allowing the NagZ products 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc tripeptide (or pentapeptide) to accumulate and presumably competitively displace UDP-MurNAc pentapeptide from AmpR, generating a complex that acts as a transcriptional activator of ampC (17). Although antipseudomonal β-lactams, such as ceftazidime, piperacillin, and cefepime, are not susceptible to this intrinsic resistance mechanism, the selection of loss-of-function mutations in ampD (20, 22, 25, 40) shunts PG recycling toward the accumulation of cytosolic 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc peptide and causes the derepression of ampC at a level of that is sufficient to confer resistance to even these β-lactams (16, 21).

P. aeruginosa has recently been found to encode three ampD homologues: ampD, ampDh2, and ampDh3. All three appear to work in concert to repress ampC induction (21); the stepwise deletion of ampD, ampDh2, and ampDh3 results in a three-step upregulation mechanism of ampC expression, with the triple null mutant exhibiting complete derepression of chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase (21). The presence of multiple ampD homologues appears to provide P. aeruginosa the ability to acquire resistance to β-lactams through the partial derepression of ampC expression via loss-of-function mutations in ampD even while maintaining its fitness and virulence by sustaining PG recycling via the activities of AmpDh2 and AmpDh3 (31). Recently, a β-lactam-resistant P. aeruginosa isolate from the lung of a CF patient was found to contain loss-of-function mutations in both ampD and ampDh3 (37); however, the inactivation of multiple ampD homologues may be uncommon, since the constitutive hyperexpression of ampC has been linked to reduced fitness (30, 31).

Given that NagZ catalyzes the formation of the inducer molecule 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc tripeptide (or pentapeptide), inhibition of the activity of this enzyme in P. aeruginosa may provide an effective strategy to prophylactically repress ampC expression during β-lactam therapy or to enhance the efficacy of antipseudomonal penicillins and cephalosporins against resistant mutants containing ampD null mutations. We recently demonstrated that a series of selective small-molecules inhibitors targeting NagZ could repress ampC induction in an Escherichia coli model system harboring the ampC-ampR operon from Citrobacter freundii (42). This model system was previously used to demonstrate that the NagZ function is required for the production of AmpC β-lactamase from a plasmid-borne ampC-ampR operon (50). The importance and functional role, however, of NagZ in gram-negative pathogens with a chromosomally encoded ampC-ampR operon have not yet been investigated.

To understand the role of NagZ in the AmpC β-lactamase induction pathway of P. aeruginosa, we have inactivated nagZ (PA3005) in P. aeruginosa reference strain PAO1 (41) and in an AmpD-deficient strain of PAO1 (strain PAΔDDh2Dh3, in which ampD [D], ampDh2 [Dh2], and ampDh3 [Dh3] are inactivated) (21) (Table 1). We have measured the sensitivities of the nagZ null mutants to antipseudomonal β-lactams and demonstrate that the inactivation of nagZ reduces both intrinsic β-lactam resistance and the high antipseudomonal β-lactam resistance associated with the loss of AmpD activity. We also demonstrate that AmpC-mediated resistance to antipseudomonal β-lactams can be suppressed in P. aeruginosa by using a potent and selective small-molecule inhibitor of NagZ. The results suggest that the blockage of NagZ activity could provide an effective strategy to enhance the efficacies of β-lactams against gram-negative pathogens encoding inducible chromosomal AmpC and counteract the hyperinduction of AmpC β-lactamase that occurs from the selection of ampD mutants during β-lactam therapy.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and bacterial strains

| Plasmid or strain | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pEX18Tc | TcroriT+sacB+, gene replacement vector with MCS from pUC18 | 15 |

| pUCP27 | Tcr pUC18-derived broad-host-range vector | 51 |

| pUCPNagZ | Tcr; pUCP27 containing wild-type PAO1 nagZ gene (PA3005) | This work |

| pUCGM | Apr Gmr; source of Gmr cassette (aacC1 gene) | 15 |

| pEXNagZGm | pEX18Tc containing 5′ and 3′ flanking sequences of nagZ::Gm | This work |

| E. coli S17-1 | RecA pro (RP4-2 Tet::Mu Kan::Tn7) | 39 |

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PAO1 | Reference strain, completely sequenced | 41 |

| PAΔDDh2Dh3 | PAO1 ΔampD::lox ΔampDh2::lox ΔampDh3::lox | 21 |

| PAΔnagZ | PAO1 ΔnagZ::Gm | This work |

| PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ | PAO1 ΔampD::lox ΔampDh2::lox ΔampDh3::lox ΔnagZ::Gm | This work |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and antibiotics and reagents.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (41) was used as the wild-type strain for this work. Growth media were from Becton Dickinson Canada (Oakville, Ontario, Canada). All mutant derivatives of PAO1, plasmid constructs, and E. coli strains are described in Table 1. Etest strips were from AB Biodisk (Solna, Sweden), and antibiotic powders for liquid MIC measurements were from Sigma-Aldrich Canada (Oakville, Ontario, Canada). All additional chemicals and enzymes were of laboratory reagent grade. P. aeruginosa NagZ was recombinantly expressed and purified as previously described (43). The Ki value of O-(2-deoxy-2-N-2-ethylbutyryl-d-glucopyranosylidene)amino N-phenylcarbamate (EtBuPUG) was determined against P. aeruginosa NagZ essentially as described previously (42).

Insertional inactivation of nagZ gene.

By using purified PAO1 genomic DNA as the template, a 950-bp region upstream of and including the first 31 bp of nagZ (PA3005) (Entrez GeneID 880216) was amplified by PCR with primers NagZ-FH1 and NagZ-RP1 (Table 2) and restricted with HindIII and PstI. A second 1,015-bp region containing the last 246 bp of nagZ and adjacent downstream DNA was amplified with primers NagZ-FP2 and NagZ-RE2 (Table 2) and restricted with PstI and EcoRI. The restricted amplicons were ligated together via a three-way reaction into pEX18Tc (15) that had been linearized with HindIII and EcoRI. The ligation reaction was used to transform chemically competent E. coli NM522 cells, and transformants were selected on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar supplemented with 5 μg/ml tetracycline. Recombinant plasmid pEXNagZ was isolated from a single transformant, and its presence was verified by restriction analysis and DNA sequencing. To generate the mobilizable suicide plasmid pEXNagZGm, the gentamicin resistance cassette (aacC1) was excised from plasmid pUCGm (38) by PstI restriction and ligated into the unique PstI site that had been introduced by PCR into the truncated nagZ gene of pEXNagZ. Recombinant pEXNagZGm was isolated from a single transformant of E. coli NM522 that had been selected on LB agar supplemented with 20 μg/ml gentamicin. The presence of the plasmid was verified by restriction analysis and was then transferred into PAO1 and the triple ampD null mutant PAΔDDh2Dh3 (Table 1) by diparental mating on LB agar with E. coli S17-1 as the donor (39) to create PAΔnagZ and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ, respectively (Table 1). Merodiploids were selected on Pseudomonas isolation agar supplemented with 50 μg/ml gentamicin, followed by the selection of double crossovers with 5% sucrose. The existence of mutants was verified by assaying for resistance to gentamicin and susceptibility to tetracycline by replica plating. The presence of the insertion was confirmed by restriction analysis and sequencing of the PCR products generated with oligonucleotides which primed to sites on the genome flanking that which was cloned into suicide plasmid pEXNagZGm.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Restriction enzyme | PCR product length (bp) | Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NagZ-FH1 | CATATCAAGCTTCCAGTCGGAAACCGTCGAACGC | HindIII | 950 | NagZ inactivation |

| NagZ-RP1 | GATATACTGCAGCGATGTCGAGCATCAGAGAGCC | PstI | ||

| NagZ-FP2 | GATATACTGCAGGCCCATGTGGTCGGCGAC | PstI | 1,015 | NagZ inactivation |

| NagZ-RE2 | GATATAGAATTCTGGCCGCCTAGCCGGCCAGG | EcoRI | ||

| NagZ-FpUC | GATATACTGCAGAAGAAGGAGATATACATATGCAAGGCTCTCTGATGCTC | PstI | 1,057 | NagZ complementation |

| NagZ-RpUC | GATATAGGATCCTCAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGATCAATCAGTTGCGCAGC | BamHI |

Primer sequences were obtained from the published PAO1 genome (41). Sites for restriction endonucleases are underlined. The ribosome-binding site derived from pET vector T7 is shown in italics. The His6 fusion tag added to the C terminus of the nagZ open reading frame of the complementation plasmid pUCPnagZ is shown in boldface.

Cloning of wild-type nagZ for complementation studies.

Full-length nagZ was amplified from purified P. aeruginosa PAO1 genomic DNA by PCR with Pfu polymerase and oligonucleotide primers NagZ-FpUC and NagZ-RpUC (Table 2). The PCR amplicon was restricted with PstI and BamHI and ligated into pUCP27 (51). The ligation reaction was used to transform chemically competent E. coli NM522 cells, and transformants were selected on LB agar supplemented with 5 μg/ml tetracycline. The recombinant plasmid was isolated from a single transformant, and its presence was verified by restriction analysis and DNA sequencing. The resulting nagZ expression plasmid, pUCPNagZ (Table 1), was electroporated into the nagZ-deficient P. aeruginosa PAO1 mutants PAΔnagZ and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ (Table 1). Transformants were selected on LB agar supplemented with 100 μg/ml tetracycline to generate strains PAΔnagZ(pUCPNagZ) and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ(pUCPNagZ), respectively (Table 1). The inclusion of a His6 tag fused to the C terminus of the nagZ open reading frame was used to verify the expression of the recombinant protein by Western blotting (data not shown).

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

MICs were determined with Etest strips (AB Biodisk) on Mueller-Hinton agar plates, according to the manufacturer's recommendations, or by the broth microdilution method, as recommended by the CLSI (formerly the NCCLS) (5), with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton medium. For broth microdilution, appropriate serial dilutions of the β-lactam antibiotics were prepared in 96-well plates, and each concentration was assayed in 200 μl of broth inoculated with ∼104 cells taken from starter cultures grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.5. MICs were determined after incubation of the plates at 37°C for 18 h in a shaker incubator. MIC measurements in the presence of the NagZ selective inhibitor EtBuPUG were carried out by preparing 96-well plates containing serial dilutions of β-lactam antibiotics in 80 μl of Mueller-Hinton broth. The volume was brought to 100 μl by addition of either 20 μl of EtBuPUG (5 mM in H2O) or 20 μl H2O. These broths were then inoculated with 100 μl of the desired culture and allowed to incubate at 37°C for 18 h. The MICs were determined from the antibiotic concentration in the wells in which no growth was observed. Susceptibility tests of strains transformed with pUCP27 or pUCPNagZ were performed as described above; however, to maintain the complementation plasmid, the broth was supplemented with 50 μg/ml tetracycline for the microdilution assays and the agar plates were supplemented with 75 μg/ml tetracycline for measurements made with Etest strips. All MICs were determined in triplicate.

Agar diffusion tests.

The appropriate bacterial culture was prepared by inoculating 5 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth with the appropriate glycerol stock, and the culture was allowed to grow at 37°C until the OD600 reached ∼0.5. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and were then resuspended in 2 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth and streaked onto Mueller-Hinton agar plates. Antibiotic discs (diameter, 6 mm) that had previously been loaded with 10 μl of EtBuPUG (3 mM) or H2O alone were placed on the agar plates. After incubation overnight at 37°C, the diameter of the inhibition zone was measured. All determinations were performed in triplicate.

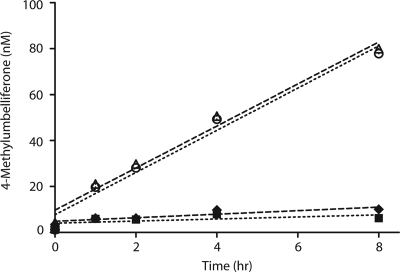

Assay for residual N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase activity.

Lysates of cells of P. aeruginosa null mutants PAΔnagZ, PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ, and PAΔDDh2Dh3 and wild-type P. aeruginosa (PAO1) (Table 1) were assayed for N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase activity by using 4-methylumbelliferyl N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide (4-MUGlcNAc) as the substrate. For each strain, 3 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth was inoculated with a few milligrams of glycerol stock and the strain was allowed to grow at 37°C to an OD600 of ∼0.5, at which time each culture was diluted to an OD600 of 0.25 with fresh Mueller-Hinton broth, allowed to grow for an additional 1.5 h at 37°C, and then harvested by centrifugation. The pellets were washed by resuspending them twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (50 mM NaPi, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl), followed by centrifugation. The supernatants were discarded, and the washed pellets were stored at −80°C. The cells in the pellets were lysed by sonication in 200 μl chilled PBS buffer, and 15 μg of protein from each lysate was assayed for N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase activity at 37°C in a total volume of 100 μl PBS supplemented with 2 mM 4-MUGlcNAc. The reactions were allowed to proceed for 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 8 h and were then quenched by addition of 0.9 ml of 0.1 M glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 10.7). Liberated 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MU) was detected by measurement of the fluorescence by using an excitation wavelength of 360 nm and monitoring of the emission at 450 nm. The assays were carried out in triplicate; and controls included thermally denatured lysates (heated to 100°C for 20 min), native lysates in PBS lacking 4-MUGlcNAc, 2 mM 4-MUGlcNAc alone in PBS, and blanks containing PBS only.

Quantification of β-lactamase activity.

Strains PAO1, PAΔnagZ, PAΔDDh2Dh3, and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ were grown in 5 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth at 37°C to an OD600 of ∼0.5. As described previously (21), to determine the β-lactamase specific activity (nanomoles of nitrocefin hydrolyzed per minute per milligram of protein) postinduction, strains were cultured in the presence of 50 μg/ml cefoxitin for 3 h at 37°C and the resulting β-lactamase activities were compared to the same strains cultured under the same conditions without cefoxitin. The β-lactamase specific activity was determined from crude sonic lysates in triplicate at 37°C by using a continuous assay procedure by following the linear rate of liberation of 2,4-dinitrophenolate from nitrocefin (initial concentration, 100 μM), as determined by measurement of the absorption at 485 nm. The reactions (500 μl) were initiated by the addition of 5 μl of appropriately diluted supernatant and were monitored for 5 min.

RESULTS

To demonstrate the role of NagZ in antipseudomonal β-lactam resistance, we inactivated nagZ (PA3005) in strain PAO1 (41) and in the highly antipseudomonal β-lactam-resistant triple ampD null mutant PAΔDDh2Dh3 (21) via insertional inactivation, creating strains PAΔnagZ and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ, respectively (Table 1). Strains PAΔnagZ and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ did not exhibit any change in growth rate or morphology relative to the growth rate and morphology of the parental strains. Given that there are multiple ampD homologues in P. aeruginosa, we speculated that there might be other enzymes with NagZ activity. To investigate if nagZ (PA3005) was the only gene encoding an enzyme with N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase activity, we assayed cellular extracts of PAΔnagZ and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ for residual activity using the substrate 4-MUGlcNAc (Fig. 2). We found that both PAΔnagZ and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ were devoid of N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase activity. The presence of only one protein with NagZ activity in PAO1 is in agreement with the observations made for E. coli, in which only one protein with NagZ activity is found (3), and our finding that only one protein with NagZ activity was identified in PAO1 by using an activity-based proteomics probe (43). NagZ appears to be solely responsible for the removal of GlcNAc from the GlcNAc-1,6-anhydro-MurNAc peptide in these microbes.

FIG. 2.

NagZ activity assay of wild-type P. aeruginosa and deletion mutants. NagZ activity was determined from sonicated cultures by monitoring 4-MU liberation, as described in Materials and Methods. ○, PAO1; ▪, PAΔnagZ; ▵, PAΔDDh2Dh3; ⧫, PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ. The level of 4-MU liberation from PAΔnagZ (▪) and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ (⧫) is the same as that from thermally denatured PAO1, PAΔnagZ, PAΔDDh2Dh3, and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ, confirming the absence of NagZ activity in these strains.

NagZ activity is required to produce the AmpR inducer molecule 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc tripeptide (or pentapeptide); thus, the inactivation of nagZ in P. aeruginosa should block the β-lactam-mediated induction of AmpC β-lactamase expression and thereby increase the susceptibility of the organism to these antibiotics. Our findings are in accord with this hypothesis. The most pronounced effect on β-lactam resistance was observed when nagZ was inactivated in PAΔDDh2Dh3 (Table 3), a triple ampD null mutant previously shown to exhibit the complete derepression of ampC and high, clinical-level resistance to antipseudomonal β-lactams (21) (Table 3). As shown previously (21), PAΔDDh2Dh3 displayed high-level resistance to all antipseudomonal β-lactams tested except imipenem (a carbapenem resistant to hydrolysis by AmpC) compared to the level of resistance of PAO1 (Table 3). The MICs of aztreonam, ceftazidime, piperacillin, and piperacillin-tazobactam were significantly above their respective CLSI resistance breakpoints when their activities against PAΔDDh2Dh3 were tested. Despite a significant increase in the MIC (24-fold), however, we found that the MIC of cefepime remained slightly below its CLSI resistance breakpoint when its activity against PAΔDDh2Dh3 was tested (Table 3). Notably, the inactivation of nagZ in PAΔDDh2Dh3 yielded a mutant (PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ) with significantly increased susceptibility to all antipseudomonal β-lactams tested. Compared to the susceptibility of PAΔDDh2Dh3, the nagZ null mutant PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ was 4- to 6-fold more susceptible to aztreonam, ceftazidime, and cefepime and 10- to 16-fold more susceptible to piperacillin and piperacillin-tazobactam (Table 3). The increased susceptibility from the loss of NagZ activity was sufficient to reduce the MICs for all these antipseudomonal β-lactams to well below their respective CLSI resistance breakpoint concentrations (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

MICs of antibiotics for strain PAO1 and nagZ and/or ampD null mutants of P. aeruginosa

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATM (≤8->16) | CAZ (≤8->16) | PIP (≤64->64) | PIP-TZ (≤64->64) | FEP (≤8->16) | IMP (≤4->8) | FOX (NA) | CIP (≤1->2) | |

| PAO1 | 1b | 1b | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | 1,600b | 0.2b |

| PAΔnagZ | 0.25b | 0.5b | 1 | 1.5 | 0.38 | 2 | 800b | 0.2b |

| PAΔDDh2Dh3 | 24 | 48 | >256 | ≥256 | 12 | 1.5 | 3,200b | 0.2b |

| PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ | 4 | 12 | 24 | 16 | 3 | 1.5 | 2,400b | 0.2b |

| Complementation with wild-type nagZ | ||||||||

| PAΔnagZ(pUCP27) | 600b | |||||||

| PAΔnagZ(pUCPnagZ) | 1,200b | |||||||

| PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ(pUCP27) | 6 | 12 | 16 | |||||

| PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ(pUCPnagZ) | 24 | 48 | 256 | |||||

ATM, aztreonam; CAZ, ceftazidime; FEP, cefepime; PIP, piperacillin; PIP-TZ, piperacillin-tazobactam; IMP, imipenem; FOX, cefoxitin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; NA, not available. MICs were determined by using Etest strips, unless otherwise indicated. CLSI resistance breakpoints (in μg/ml) are shown in parentheses after the abbreviation for each antibiotic. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

MICs were determined by broth microdilution, as recommended by the CLSI (see Results).

Wild-type P. aeruginosa (PAO1) is highly susceptible to antipseudomonal β-lactams; it is believed that in PAO1 these antibiotics do not induce a sufficient amount of PG fragmentation to saturate endogenous AmpD activity and thereby increase the level of ampC expression. Accordingly, the inactivation of nagZ in PAO1 (PAΔnagZ) resulted in smaller increases in susceptibility to antipseudomonal β-lactams when the MICs were measured with Etest strips. To further investigate if PAΔnagZ was exhibiting increased susceptibility to β-lactams, we reevaluated the antibiotic susceptibility of the mutant by measuring the changes in the MICs of ceftazidime and aztreonam for PAΔnagZ compared to the MICs for PAO1 using the broth microdilution method with a narrow serial dilution range (32 to 0.0625 μg/ml) and cefoxitin, a very strong inducer of AmpC β-lactamase expression. Using broth microdilution and appropriate antibiotic dilutions, we confirmed that, compared to the MIC for PAO1, PAΔnagZ exhibited twofold (0.5 μg/ml) and fourfold (0.25 μg/ml) reductions in MICs for the antipseudomonal β-lactams ceftazidime and aztreonam, respectively, and a twofold reduction in the MIC for cefoxitin (Table 3). To confirm that the observed increases in susceptibility were due to reduced levels of AmpC production, we used the substrate analogue nitrocefin to measure the basal and the induced levels of β-lactamase specific activity in PAΔnagZ and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ and compared these values to the β-lactamase specific activities of the respective parental strains PAO1 and PAΔDDh2Dh3 (Table 4). As expected, we found significant reductions in the β-lactamase specific activities for both nagZ null mutants, and these were consistent with the MICs presented in Table 3. To verify that the changes in the MICs resulting from the loss of NagZ activity were specific to β-lactam antibiotics, we measured the MIC of the non-β-lactam ciprofloxacin against all four strains. We found that all strains were equally susceptible to this antibiotic (MIC, 0.2 μg/ml), further supporting the specific role of NagZ in the AmpC induction pathway. Finally, as shown in Table 3, an expression plasmid harboring nagZ was found to completely transcomplement the β-lactam resistance phenotypes of both PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ and PAΔnagZ, demonstrating that the observed changes in the β-lactam resistance profiles were due solely to the loss of NagZ activity.

TABLE 4.

Levels of β-lactamase specific activity under basal and cefoxitin-induced conditions

| Strain | Avg β-lactamase sp acta ± SD

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Basal | Inducedb | |

| PAO1 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 230 ± 20 |

| PAΔnagZ | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 95 ± 7.8 |

| PAΔDDh2Dh3 | 3,792 ± 121 | 3,935 ± 11 |

| PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ | 288 ± 32 | 1,019 ± 64 |

Specific activity is in units of nanomoles of nitrocefin hydrolyzed per minute per milligram of protein.

Induction was carried out by culturing the strains in the presence of 50 μg/ml cefoxitin for 3 h 37°C.

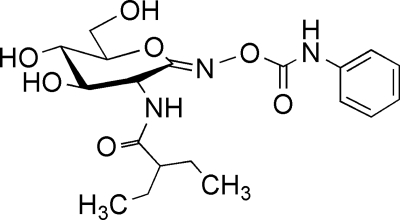

Given our findings that the genetic inactivation of nagZ attenuates β-lactam resistance in both PAO1 and PAΔDDh2Dh3, we speculated whether the NagZ selective inhibitor EtBuPUG (Fig. 3) could also be used to suppress antipseudomonal β-lactam resistance in PAO1 and in a series of ampD null mutants of P. aeruginosa. EtBuPUG has been shown to suppress AmpC production in E. coli (harboring an ampC-ampR operon from C. freundii) when it is coadministered with β-lactams, yet EtBuPUG itself does not exhibit antimicrobial properties (42). Consistent with this finding, we found the growth rates of both EtBuPUG-treated P. aeruginosa and control cultures lacking antibiotic to be identical (data not shown). However, as shown in Table 5, EtBuPUG suppressed the resistance of PAO1 and AmpD-deficient strains of P. aeruginosa to the antipseudomonal β-lactams ceftazidime and aztreonam. The presence of 0.5 mM EtBuPUG in the broth microdilution assays enhanced the efficacies of ceftazidime and aztreonam against PAO1 by twofold and fourfold, respectively (Table 5). This finding agrees with the twofold (ceftazidime) and fourfold (aztreonam) increases in the susceptibility of PAΔnagZ to these antibiotics compared to the susceptibility of PAO1 (Table 3). Thus, the results indicate that EtBuPUG can enter the PAO1 cytosol and block a sufficient amount of NagZ activity to suppress AmpC production and enhance the antimicrobial efficacies of these β-lactams against PAO1. In contrast, however, we found that EtBuPUG enhanced the efficacy only of aztreonam (twofold reduction in MIC) and not that of ceftazidime against the triple ampD null mutant (PAΔDDh2Dh3) (Table 5).

FIG. 3.

Structure of the NagZ selective inhibitor EtBuPUG. Designed to resemble the putative oxocarbenium ion-like transition state used by NagZ, EtBuPUG is a potent inhibitor of P. aeruginosa NagZ (Ki = 3.5 μM) and is highly selective for this enzyme and other CAZy family 3 β-glucosaminidases (42).

TABLE 5.

Susceptibilities of PAO1 and ampD null mutants to ceftazidime and aztreonam in the presence or absence of EtBuPUGa

| Strain | MICb (mg ml−1)

|

Antibiotic clearing radius (mm)c

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftazidime

|

Aztreonam

|

Ceftazidime

|

Aztreonam

|

|||||

| −I | +I | −I | +I | −I | +I | −I | +I | |

| PAO1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25 | 11.4 | 13.1 | 12.5 | 15.1 |

| PAΔD | 8 | 4 | 6 | 3 | ||||

| PAΔDh2 | 0.75 | 0.19 | 1 | 0.25 | 10.1 | 12.3 | 11.8 | 14.0 |

| PAΔDh3 | 1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.75 | ||||

| PAΔDDh2 | 12 | 6 | 16 | 8 | ||||

| PAΔDDh3 | 48 | 48 | 16 | 8 | ||||

| PAΔDh2Dh3 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | ||||

| PAΔDDh2Dh3 | 48 | 48 | 24 | 12 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 10.7 | 11.9 |

The bacterial strains were treated with the NagZ selective inhibitor EtBuPUG (+I) or were not treated with EtBuPUG (−I).

The MIC was determined by the broth microdilution method. Measurements were performed in triplicate.

Sensitivity was determined by an agar diffusion assay. Filter discs (diameter, 6 mm) loaded with 30 μg of ceftazidime or aztreonam with or without the inhibitor EtBuPUG were placed onto an agar plate inoculated with the indicated strain. After incubation overnight, the radius (from the center of the disc) of the zone of clearance was measured.

The inactivation of all three ampD homologues is not required for P. aeruginosa to develop clinical resistance to antipseudomonal β-lactams. The partial derepression of ampC via loss-of-function mutations in ampD alone appears to be sufficient to provide clinical resistance and maintain the fitness an virulence necessary to survive in the environment of the lungs of patients with CF (31). To determine if EtBuPUG could enhance the antimicrobial efficacy of ceftazidime or aztreonam against P. aeruginosa mutants with partially derepressed ampC phenotypes, we tested the activity of the inhibitor against strains with all combinations of ampD, ampDh2, and ampDh3 inactivation. As shown previously (21), the inactivation of ampDh2 (PAΔDh2) or ampDh3 (PAΔDh3) alone or in combination (PAΔDh2Dh3) did not significantly increase the resistance of P. aeruginosa to ceftazidime or aztreonam, while the inactivation of ampD (PAΔD) increased the MICs of ceftazidime and aztreonam eight- and sixfold, respectively. Interestingly, a combination of 0.5 mM EtBuPUG with either ceftazidime or aztreonam resulted in a twofold reduction in the MICs for both PAΔD and PAΔDh3 and a fourfold reduction in the MICs for PAΔDh2. Thus, whereas EtBuPUG did not suppress the resistance phenotype of the triple ampD null mutant PAΔDDh2Dh3, it did enhance the efficacies of these antibiotics against the clinically relevant ampD null mutant PAΔD and against PAΔDh2 and PAΔDh3. Although loss-of-function mutations in ampD alone, as opposed to its homologues, appears to be the most common resistance-conferring mutation that is selected for clinically (20, 22, 25, 40), a clinical isolate of P. aeruginosa was recently reported to contain loss-of-function mutations in both ampD and ampDh3 (37). This mutant with double mutations (PAΔDDh3) has been shown to generate a highly resistant phenotype with a level of resistance that is comparable to that of triple ampD null mutant PAΔDDh2Dh3. Interestingly, while 0.5 mM EtBuPUG could not suppress the resistance of PAΔDDh3 to ceftazidime, it did cause a twofold suppression of resistance of this double mutant to aztreonam. Thus, EtBuPUG enhanced the efficacies of antispseudomonal β-lactams against two clinically relevant mutants of P. aeruginosa, PAΔD and PAΔDDh3.

DISCUSSION

Due to the constant and rapid evolution of bacterial antibiotic resistance mechanisms and the limited efficacies of clinically available β-lactamase inhibitors against AmpC (27, 44), alternative approaches to surmount AmpC-mediated antibiotic resistance are needed. Given that NagZ is highly conserved in gram-negative bacteria (3, 47) and is responsible for catalyzing the formation of the ampC inducer molecule 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc tripeptide (or pentapeptide) (3), the blockage of NagZ activity may provide a novel strategy to enhance the efficacies of β-lactams against bacteria encoding inducible ampC. The consequence of its inhibition would be the suppression of intrinsic ampC induction and the hyperinduction that occurs from the selection of ampD null mutants. We now show that blockage of the function of NagZ in P. aeruginosa via genetic inactivation or by the use of a selective small-molecule inhibitor can attenuate β-lactam resistance in a clinically significant pathogen that encodes an endogenous chromosomal ampC-ampR operon. The two- to fourfold increase in susceptibility of PAΔnagZ to β-lactam antibiotics is consistent with the fourfold increase in susceptibility to β-lactams found when nagZ was deleted from E. coli harboring a plasmid-borne ampC-ampR operon (50) and is also consistent with the reduction in the level of AmpC production in this model system that was achieved by using the NagZ inhibitor EtBuPUG (42). Notably, the attenuation of β-lactam resistance was particularly profound (up to 16-fold) when nagZ was genetically inactivated in PAΔDDh2Dh3, a strain that otherwise exhibits extremely high levels of resistance to antipseudomonal β-lactams due to the inactivation of all three ampD homologues that are required to coordinately repress ampC expression. This observation highlights the requirement of NagZ activity for the induction of AmpC production in P. aeruginosa and underscores that the loss of NagZ activity can effectively reverse the extremely high antipseudomonal β-lactam resistance phenotype of a mutant that is completely deficient in AmpD amidase activity.

Although loss-of-function mutations in ampD alone are a leading cause of antipseudomonal β-lactam resistance in P. aeruginosa (1, 20), it has recently been shown that additional loss-of-function mutations can be selected for in ampDh3 (37) to yield a resistance phenotype very similar to that of strain PAΔDDh2Dh3. Thus, it is encouraging to find that even in the PAΔDDh2Dh3 background, the inactivation of nagZ could attenuate β-lactam resistance sufficiently to bring the MICs for all antipseudomonal β-lactams assayed to well below their respective CLSI resistance breakpoints. This profound effect arising from the inactivation of nagZ provides good support for the targeting of NagZ with inhibitors as a method of reducing antibiotic resistance in antipseudomonal agent-resistant P. aeruginosa strains.

Despite our finding that the inactivation of nagZ in PAΔDDh2Dh3 could significantly attenuate the resistance of this strain to antipseudomonal β-lactams, the resulting MICs were not reduced to the values observed for PAO1 (Table 3). This residual resistance in the absence of NagZ activity cannot be attributed to the presence of an additional nagZ homologue, since we found that both PAΔnagZ and PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ were devoid of N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase activity (Fig. 2). A possible reason for the residual β-lactam resistance observed in PAΔDDh2Dh3nagZ may be explained by an observation of Jacobs et al., who found that in vitro, the apo form of AmpR constitutively activates ampC expression and becomes a repressor of ampC transcription only after the addition of UDP-MurNAc pentapeptide (17). The disruption of PG recycling by the removal of AmpD and NagZ activity may render the mutant reliant on the de novo synthesis of UDP-MurNAc pentapeptide. The consequence of this may be that although the production of the AmpR-activating molecule 1,6-anhydromuropeptide has been blocked, the disruption of PG recycling may not allow the mutant to sustain sufficient cytoplasmic concentrations of UDP-MurNAc pentapeptide to fully repress AmpR. Consistent with this view, the suppression of inducible β-lactamase resistance has been observed in cell division mutants that accumulate cytosolic UDP-MurNAc pentapeptide, presumably because increased amounts of the molecule outcompete the incoming anhydromuropeptide inducer and ensure the continued repression of AmpR (45). Regardless, further studies will be required to clarify the precise molecular roles of these inducer and repressor molecules.

The genetic inactivation of nagZ in PAO1 and PAΔDDh2Dh3 provides a useful benchmark against which the ability of small-molecule inhibitors of NagZ to attenuate AmpC-mediated resistance in P. aeruginosa may be measured. We have previously shown that this resistance mechanism can be attenuated in E. coli isolates harboring the ampC-ampR operon by blocking the formation of 1,6-anhydromuropeptide using potent and selective small-molecule inhibitors of NagZ derived from O-(2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-glucopyranosylidene)amino-N-phenylcarbamate (PUGNAc) (42). PUGNAc is a nonselective N-acetyl-β-hexosaminidase inhibitor that competitively inhibits both NagZ and functionally related human enzymes belonging to glycoside hydrolase families GH20, GH84, and GH89 (42) (8). However, the use of a three-dimensional crystal structure of PUGNAc in complex with NagZ from Vibrio cholerae facilitated our development of 2-N-acyl derivatives of PUGNAc that were specific for NagZ over the functionally related human enzymes from glycoside hydrolase families GH20 and GH84 (42). The recently determined crystal structure of an α-N-acetylglucosaminidase from GH89 reveals that, unlike NagZ, GH89 glycosidases have a restrictive active-site pocket (8) that also precludes the binding of these PUGNAc derivatives. EtBuPUG was the derivative selected for use in this study since it retains good potency and displays optimal selectivity for P. aeruginosa NagZ.

The use of EtBuPUG in combination with ceftazidime or aztreonam attenuated the resistance to these antibiotics (Table 5) to levels comparable to the level of resistance observed for PAΔnagZ (Table 3), and we hasten to add that EtBuPUG also enhanced the efficacies of these β-lactams against the clinically relevant ampD deletion mutant PAΔD (Table 5). Although EtBuPUG was found to enhance the efficacy of aztreonam against PAΔDDh3, it did not enhance the efficacy of either β-lactam against PAΔDDh2Dh3 (Table 5). Comparison of this result to that achieved by our genetic inactivation of nagZ in PAΔDDh2Dh3 (Table 3) suggests that EtBuPUG may not be able to inhibit a sufficient amount of endogenous NagZ, possibly due to the limited entry of the inhibitor into the cytosol. Interestingly, however, the complete derepression of ampC expression through loss-of-function mutations in all three ampD homologues has yet to be identified clinically, probably because the complete loss of AmpD appears to reduce the viability of P. aeruginosa in vivo (31), and so this may not be a significant limitation to the strategy of inhibiting NagZ.

Our results demonstrate that the development of small-molecule inhibitors to block NagZ activity shows promise as a strategy for suppressing the antipseudomonal β-lactam resistance that arises from the selection of loss-of-function mutations in ampD and its homologues. Possible complications that might hinder such a strategy are the selection of nagZ mutations that reduce the binding affinity of the enzyme to sugar-based inhibitors. Such mutations, however, would likely compromise the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme and thus self-limit the formation of the inducer molecule that is required for the induction of ampC expression. Antipseudomonal β-lactam resistance-conferring mutations independent of ampD null mutations have also been identified in clinical isolates, and these may circumvent a strategy targeting NagZ. Such mutations, including those occurring in ampR, are comparatively rare, however, perhaps because they are associated with the constitutive hyperproduction of AmpC, a condition that has been linked to reduced fitness (31). Finally, it is noteworthy that in addition to regulating ampC expression, AmpR also modulates the expression of extracellular proteases and other virulence factors in P. aeruginosa (24). Thus, modulation of the activity of AmpR by inhibiting NagZ may have a wide effect on the transcriptional regulation of the P. aeruginosa genome and disrupt multiple virulence pathways, in addition to suppressing the induction of AmpC β-lactamase production, a topic that we are actively exploring.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

We thank Teresa de Kievit for her technical advice and productive comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 March 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bagge, N., O. Ciofu, M. Hentzer, J. I. Campbell, M. Givskov, and N. Hoiby. 2002. Constitutive high expression of chromosomal beta-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa caused by a new insertion sequence (IS1669) located in ampD. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3406-3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartowsky, E., and S. Normark. 1991. Purification and mutant analysis of Citrobacter freundii AmpR, the regulator for chromosomal AmpC beta-lactamase. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1715-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng, Q., H. Li, K. Merdek, and J. T. Park. 2000. Molecular characterization of the beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase of Escherichia coli and its role in cell wall recycling. J. Bacteriol. 182:4836-4840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng, Q., and J. T. Park. 2002. Substrate specificity of the AmpG permease required for recycling of cell wall anhydro-muropeptides. J. Bacteriol. 184:6434-6436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2003. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, sixth edition (M7-A6). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 6.Dietz, H., D. Pfeifle, and B. Wiedemann. 1996. Location of N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanyl-d-glutamylmesodiaminopimelic acid, presumed signal molecule for beta-lactamase induction, in the bacterial cell. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2173-2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietz, H., D. Pfeifle, and B. Wiedemann. 1997. The signal molecule for beta-lactamase induction in Enterobacter cloacae is the anhydromuramyl-pentapeptide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2113-2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ficko-Blean, E., K. A. Stubbs, O. Nemirovsky, D. J. Vocadlo, and A. B. Boraston. 2008. Structural and mechanistic insight into the basis of mucopolysaccharidosis IIIB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:6560-6565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FitzSimmons, S. C. 1993. The changing epidemiology of cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. 122:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giamarellou, H. 2000. Therapeutic guidelines for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 16:103-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giwercman, B., P. A. Lambert, V. T. Rosdahl, G. H. Shand, and N. Hoiby. 1990. Rapid emergence of resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis patients due to in-vivo selection of stable partially derepressed beta-lactamase producing strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 26:247-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hancock, R. E., and D. P. Speert. 2000. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and impact on treatment. Drug Resist. Updat. 3:247-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen, C. R., T. Pressler, and N. Hoiby. 2008. Early aggressive eradication therapy for intermittent Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway colonization in cystic fibrosis patients: 15 years experience. J. Cyst Fibros. 7:523-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henrissat, B., and A. Bairoch. 1996. Updating the sequence-based classification of glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem. J. 316:695-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoang, T. T., R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. J. Kutchma, and H. P. Schweizer. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holtje, J. V., U. Kopp, A. Ursinus, and B. Wiedemann. 1994. The negative regulator of beta-lactamase induction AmpD is a N-acetyl-anhydromuramyl-l-alanine amidase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 122:159-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs, C., J. M. Frere, and S. Normark. 1997. Cytosolic intermediates for cell wall biosynthesis and degradation control inducible beta-lactam resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Cell 88:823-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs, C., L. J. Huang, E. Bartowsky, S. Normark, and J. T. Park. 1994. Bacterial cell wall recycling provides cytosolic muropeptides as effectors for beta-lactamase induction. EMBO J. 13:4684-4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacoby, G. A., and L. S. Munoz-Price. 2005. The new beta-lactamases. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:380-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juan, C., M. D. Macia, O. Gutierrez, C. Vidal, J. L. Perez, and A. Oliver. 2005. Molecular mechanisms of beta-lactam resistance mediated by AmpC hyperproduction in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4733-4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juan, C., B. Moya, J. L. Perez, and A. Oliver. 2006. Stepwise upregulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosomal cephalosporinase conferring high-level beta-lactam resistance involves three AmpD homologues. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1780-1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaneko, K., R. Okamoto, R. Nakano, S. Kawakami, and M. Inoue. 2005. Gene mutations responsible for overexpression of AmpC beta-lactamase in some clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2955-2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch, C. 2002. Early infection and progression of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 34:232-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong, K. F., S. R. Jayawardena, S. D. Indulkar, A. Del Puerto, C. L. Koh, N. Hoiby, and K. Mathee. 2005. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpR is a global transcriptional factor that regulates expression of AmpC and PoxB beta-lactamases, proteases, quorum sensing, and other virulence factors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4567-4575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindberg, F., S. Lindquist, and S. Normark. 1987. Inactivation of the ampD gene causes semiconstitutive overproduction of the inducible Citrobacter freundii beta-lactamase. J. Bacteriol. 169:1923-1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindquist, S., F. Lindberg, and S. Normark. 1989. Binding of the Citrobacter freundii AmpR regulator to a single DNA site provides both autoregulation and activation of the inducible ampC beta-lactamase gene. J. Bacteriol. 171:3746-3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livermore, D. M. 1995. β-Lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:557-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livermore, D. M. 2002. Multiple mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: our worst nightmare? Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:634-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lodge, J., S. Busby, and L. Piddock. 1993. Investigation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ampR gene and its role at the chromosomal ampC beta-lactamase promoter. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 111:315-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morosini, M. I., J. A. Ayala, F. Baquero, J. L. Martinez, and J. Blazquez. 2000. Biological cost of AmpC production for Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3137-3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moya, B., C. Juan, S. Alberti, J. L. Perez, and A. Oliver. 2008. Benefit of having multiple ampD genes for acquiring β-lactam resistance without losing fitness and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3694-3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Normark, S. 1995. β-Lactamase induction in gram-negative bacteria is intimately linked to peptidoglycan recycling. Microb. Drug Resist. 1:111-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park, J. T., and T. Uehara. 2008. How bacteria consume their own exoskeletons (turnover and recycling of cell wall peptidoglycan). Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72:211-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfeifle, D., E. Janas, and B. Wiedemann. 2000. Role of penicillin-binding proteins in the initiation of the AmpC beta-lactamase expression in Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:169-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romling, U., J. Wingender, H. Muller, and B. Tummler. 1994. A major Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone common to patients and aquatic habitats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1734-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossolini, G. M., and E. Mantengoli. 2005. Treatment and control of severe infections caused by multiresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11(Suppl. 4):17-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidtke, A. J., and N. D. Hanson. 2008. Role of ampD homologs in overproduction of AmpC in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3922-3927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schweizer, H. D. 1993. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques 15:831-834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Puhler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith, E. E., D. G. Buckley, Z. Wu, C. Saenphimmachak, L. R. Hoffman, D. A. D'Argenio, S. I. Miller, B. W. Ramsey, D. P. Speert, S. M. Moskowitz, J. L. Burns, R. Kaul, and M. V. Olson. 2006. Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:8487-8492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, I. T. Paulsen, J. Reizer, M. H. Saier, R. E. Hancock, S. Lory, and M. V. Olson. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stubbs, K. A., M. Balcewich, B. L. Mark, and D. J. Vocadlo. 2007. Small molecule inhibitors of a glycoside hydrolase attenuate inducible AmpC-mediated beta-lactam resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 282:21382-21391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stubbs, K. A., A. Scaffidi, A. W. Debowski, B. L. Mark, R. V. Stick, and D. J. Vocadlo. 2008. Synthesis and use of mechanism-based protein-profiling probes for retaining beta-d-glucosaminidases facilitate identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa NagZ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130:327-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tondi, D., F. Morandi, R. Bonnet, M. P. Costi, and B. K. Shoichet. 2005. Structure-based optimization of a non-beta-lactam lead results in inhibitors that do not up-regulate beta-lactamase expression in cell culture. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127:4632-4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uehara, T., and J. T. Park. 2002. Role of the murein precursor UDP-N-acetylmuramyl-l-Ala-gamma-d-Glu-meso-diaminopimelic acid-d-Ala-d-Ala in repression of beta-lactamase induction in cell division mutants. J. Bacteriol. 184:4233-4239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vincent, J. L. 2003. Nosocomial infections in adult intensive-care units. Lancet 361:2068-2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vocadlo, D. J., C. Mayer, S. He, and S. G. Withers. 2000. Mechanism of action and identification of Asp242 as the catalytic nucleophile of Vibrio furnisii N-acetyl-beta-d-glucosaminidase using 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-5-fluoro-alpha-l-idopyranosyl fluoride. Biochemistry 39:117-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vollmer, W., and J. V. Holtje. 2001. Morphogenesis of Escherichia coli. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:625-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vollmer, W., B. Joris, P. Charlier, and S. Foster. 2008. Bacterial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:259-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Votsch, W., and M. F. Templin. 2000. Characterization of a beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase of Escherichia coli and elucidation of its role in muropeptide recycling and beta -lactamase induction. J. Biol. Chem. 275:39032-39038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.West, S. E., H. P. Schweizer, C. Dall, A. K. Sample, and L. J. Runyen-Janecky. 1994. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 148:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]