Abstract

Coevolution of intracellular bacterial pathogens and their host cells resulted in the appearance of effector molecules that when translocated into the host cell modulate its function, facilitating bacterial survival within the hostile host environment. Some of these effectors interact with host chromatin and other nuclear components. In this report, we show that the AnkA protein of Anaplasma phagocytophilum, which is translocated into the host cell nucleus, interacts with gene regulatory regions of host chromatin and is involved in downregulating expression of CYBB (gp91phox) and other key host defense genes. AnkA effector protein rapidly accumulated in nuclei of infected cells coincident with changes in CYBB transcription. AnkA interacted with transcriptional regulatory regions of the CYBB locus at sites where transcriptional regulators bind. AnkA binding to DNA occurred at regions with high AT contents. Mutation of AT stretches at these sites abrogated AnkA binding. Histone H3 acetylation decreased dramatically at the CYBB locus during A. phagocytophilum infection, particularly around AnkA binding sites. Transcription of CYBB and other defense genes was significantly decreased in AnkA-transfected HL-60 cells. These data suggest a mechanism by which intracellular pathogens directly regulate host cell gene expression mediated by nuclear effectors and changes in host chromatin structure.

Intracellular pathogens, through longstanding associations with host cells, evolved mechanisms that promote survival within the often-hostile environment of their hosts (13). Global analysis of mammalian gene expression in response to intracellular bacteria identified major pathways affected during infection (4). However, previous studies largely focused on interactions of bacteria and/or bacterial effectors with the host cell surface and cytoplasmic signaling pathways (19). Transfer of bacterial effector proteins into the eukaryotic host cell cytoplasm is also a recognized mechanism of bacterial control over host cells for organisms such as Yersinia (29), Shigella (1), and Listeria (27). In contrast, mechanisms by which bacterial proteins enter the host cell and directly alter gene transcription are underinvestigated, and only a few bacterial molecules that enter the eukaryotic host nucleus are reported. Cytolethal distending toxin, a tripartite toxin produced by a number of bacteria, is translocated into the host cell nucleus and by exerting DNA damage leads to G2/M cell cycle arrest, cellular distention, and nuclear enlargement in intoxicated cells (17). Similarly, some proteins of the Amoeba proteus X-bacterium symbiont translocate into the nucleus and induce S-adenosylmethionine synthetase expression (22), whereas T-DNA from Agrobacterium tumefaciens is transported into the nucleus and induces plant cell transformation (20). Additionally, Shigella flexneri OspF is injected into host cells and alters host gene transcription by targeting chromatin access for the transcription factor NF-κB (2). Using Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection of granulocytes as a model, we showed that AnkA produced by this intracellular bacterium is also translocated into the host cell nucleus during infection (9, 24).

During A. phagocytophilum infection, AnkA is translocated into granulocytes (9, 15, 24), presumably by the type IV secretion system recently identified in A. phagocytophilum (18, 21). AnkA, which contains a putative eukaryotic nuclear localization sequence, then migrates to the nucleus, where it interacts with host cell heterochromatin (9, 24). Other microbial ankyrin proteins have been shown to serve as effectors for bacterial infection of host cells (23). In this report, we identify a novel molecular mechanism by which the intracellular pathogen A. phagocytophilum regulates host cell transcription. These data suggest that AnkA contributes to the transcriptional regulation of gene expression in infected granulocytes by modifying chromatin structure, establishing a link between intracellular bacterial infection and host transcriptional and functional changes involved in the pathogenesis of human granulocytic anaplasmosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cell culture.

Promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells were grown in RPMI medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cell density was kept <5 × 105 cells/ml by diluting with fresh medium every 3 days.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum culture and isolation.

HL-60 cells were infected with A. phagocytophilum (Webster strain) as described elsewhere (14). Briefly, the cells were infected with a frozen stock of A. phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells and were grown in RPMI medium supplemented with 1% FBS at 2 × 105 cells/ml until >90% of the HL-60 cells were infected. Uninfected HL-60 cells were used to adjust the infection level to 10% as needed. To isolate A. phagocytophilum, 2 × 107 infected cells were collected by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min and washed with 0.9% NaCl. The cells were resuspended in 3.5 ml of ice-cold hypotonic buffer (10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9) and disrupted using a French press (3/8-in-diameter chamber, 1,500 lb/in2). Nuclei and cell debris were removed by low-speed centrifugation (1,000 × g, 5 min), and A. phagocytophilum organisms were collected from the supernatant by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 30 min. The bacterial preparation was finally resuspended in RPMI medium for in vitro infection of neutrophils or HL-60 cells. To obtain heat-killed A. phagocytophilum, the suspension of purified bacteria was incubated at 80°C for 20 min. Samples of HL-60 cells exposed to live or killed A. phagocytophilum taken at 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 18, and 24 h postexposure were used for cell fractionation, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) or analysis of gene expression.

Cell fractionation and immunoblotting.

Nuclear extracts from 2 × 107 A. phagocytophilum-infected or uninfected HL-60 cells or neutrophils were prepared using NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents (Pierce). Samples of the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) to study binding of proteins to the CYBB promoter or by immunoblotting to determine the presence of AnkA and Msp2 in these fractions. Approximately 10 μg total protein extract was electrophoresed in a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The blot was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk, probed with a 1:1,000 dilution of either AnkA monoclonal antibody (MAb) IE3 (9) or Msp2 MAb 20B4 and incubated with goat anti-mouse alkaline phosphatase conjugate (KPL). The blots were developed by chemiluminescence using Immun-Star AP substrate (Bio-Rad) and exposed to X-ray film. AnkA and Msp2 band intensities were determined by densitometry. Band intensities were determined by densitometry using the public domain, free software ImageJ, Image processing, and analysis in Java (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Neutrophil isolation and infection.

Neutrophils were isolated from 50 ml of EDTA-anticoagulated blood from consenting healthy volunteers as described before (10). Approval was obtained from the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board prior to these studies. Briefly, an equal volume of 3% dextran was added to the blood, mixed, and incubated for 30 min without agitation. The upper layer containing plasma and white blood cells was transferred to a fresh tube, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 0.9% NaCl, layered on Ficoll-Hypaque solution, and centrifuged at 500 × g for 40 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in cold 0.2% NaCl to lyse the contaminating erythrocytes, and 1.8% NaCl was added after 30 s to restore the osmolarity. Finally, the neutrophils were resuspended in 5 ml of RPMI medium supplemented with 5% FBS and used immediately for in vitro infection with A. phagocytophilum at a multiplicity of infection of 10 bacteria to 1 neutrophil.

ChIP and identification of AnkA-bound sequences.

The method used for the immunoprecipitation of AnkA-bound genomic DNA sequences was modified from a method previously described (26). Heavily infected HL-60 cells (108 cells) were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Chromatin was sheared four times for 15 s using a Branson Sonifier 250 at 1.5 constant output power. AnkA-bound genomic DNA sequences were immunoprecipitated using the AnkA IE3 MAb. To study changes in the histone code, anti-acetyl-histone 3 (Ac-H3) (Millipore) and anti-monomethyl-histone 3 (Me-H3) (Millipore) were used. Mock (no DNA) and negative control antibody (Msp2 MAb) ChIPs were also included as controls. Total chromatin was used to normalize for differences in starting DNA concentration. Immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were amplified by ligation-mediated PCR (LM-PCR) (26). Universal primer sequences were ligated to the ends of the immunoprecipitated DNA, and the AnkA-bound DNA was amplified using these universal primers. PCR fragments were then cloned into the pGEM-T-easy vector (Promega) and sequenced. Alternatively, AnkA binding sites were identified by quantitative real-time PCR using primer sets spanning the CYBB locus (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The relative enrichment of each DNA fragment was calculated from the difference of the threshold cycle number with respect to the negative antibody control ChIP and normalized to the total chromatin control. Experiments were repeated three times, and the average of the three determinations was calculated.

Expression of AnkA in E. coli and mammalian cells.

The gene encoding AnkA was amplified by PCR from A. phagocytophilum Webster strain genomic DNA using primers F5-AnkA and F3-AnkA (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). The ankA coding sequence was cloned into the HindIII and KpnI restriction sites of the pFLAG-CTC vector (Sigma) for expression in E. coli. Recombinant protein was purified by FLAG affinity chromatography (Sigma) following the manufacturer's recommendations. The sequence encoding AnkA was also cloned into the KpnI and XhoI restriction sites of the pEYFP-C1 expression vector (Clontech BD Biosciences), to obtain plasmid pEYFP-AnkA, which encodes the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP)-AnkA fusion protein under control of the cytomegalovirus promoter. Plasmids were purified using the EndoFree plasmid isolation kit (Qiagen) and were transfected into HL-60 cells using Amaxa Nucleofector technology, solution T, program U-14 (Amaxa, Germany). After transfection, cells were harvested and used for gene expression analysis. The empty vector, pEYFP-C1, was used as a control.

Protein transfection.

To determine the effect of AnkA on granulocyte gene expression, HL-60 cells were transfected with purified recombinant AnkA (rAnkA) protein using the BioPORTER protein delivery system (Sigma). rAnkA protein (5 μg) was incubated at room temperature with BioPORTER reagent for 5 min. The reaction volume was adjusted to 0.5 ml with RPMI, and the mixture was added to 2 × 106 HL-60 cells. A BioPORTER-only (no protein) control was included in the experiment. After 22 h at 37°C, the transfected cells were collected for analysis of CYBB gene expression by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR).

Reporter assay.

Plasmid pCYBB-LacZ, kindly donated by Erol Fikrig, Yale University, was used to express the lacZ gene under the control of the promoter fragment from position −209 to +12 of the CYBB gene (28). The reporter plasmid was cotransfected with plasmid pEYFP-AnkA to determine the effect of AnkA on reporter expression using Amaxa Nucleofection technology as described above. Plasmid vector pEYFP-C1 was used as control. β-Galactosidase expression was measured using the β-galactosidase microtiter plate assay (Invitrogen). Briefly, transfected cells were harvested, resuspended in lysis buffer, and transferred to a 96-well plate. Following lysis of the cells via the freeze-thaw method, cleavage buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside was added and the plate was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Stop buffer was added to each well and the absorbance read at 405 nm. The amount (nmol) of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside hydrolyzed was expressed as (optical density at 405 nm × volume [μl])/4.5 μl/[nmol cm] × 1 cm).

EMSA.

Purified rAnkA or nuclear extracts from uninfected or A. phagocytophilum-infected cells were assayed by EMSA for their ability to bind to specific DNA probes. cDNA oligonucleotides spanning the CYBB proximal promoter (or containing mutated sequences) were synthesized (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Oligonucleotides were biotinylated by the supplier or using the biotin 3′ end DNA labeling kit (Pierce). Equal amounts of complementary oligonucleotides were mixed, denatured at 95°C for 5 min, and slowly cooled to room temperature to anneal, resulting in a 15 μM solution of biotinylated, double-stranded oligonucleotide. EMSA reactions were performed using the LightShift chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Pierce) following the manufacturer's instructions. Reactions were carried out in 1× LightShift binding buffer for 30 min on ice. Approximately 20 fmol DNA probe was incubated with protein at 25 ng/μl. To confirm AnkA binding specificity, AT stretches within the AnkA binding sequences were disrupted by inserting bases CGGGCGCC (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Loading buffer was added, and the samples were electrophoresed in 0.5× Tris-buffered EDTA at 100 V for approximately 45 min in a 4% polyacrylamide gel. The content of the gel was transferred to a nylon membrane for 30 min and cross-linked using a UV cross-linker at 120 mJ/cm2 for 1 min. The membrane was then blocked, washed, and exposed to X-ray film following the manufacturer's protocol.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR.

To study the levels of expression of selected genes, total RNA from approximately 2 × 106 transfected or A. phagocytophilum-infected cells was purified using RNeasy RNA extraction kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from the transcripts of the genes BPI, MPO, CYBB, RAC2, MYC, and FTH and amplified using SuperScript one-step RT-PCR (Invitrogen) using the primers described in Table S1 in the supplemental material. For quantitative real-time PCR analysis, SYBR green Supermix was used in an iQ5 thermocycler (Bio-Rad). All results were normalized to human ACTB.

Statistical methods.

Statistical analysis was carried out by standard methods. Transcriptional levels in transfected cells were compared to those in control cells using Student's t test. P values smaller than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Error bars used throughout indicate standard error of the mean.

RESULTS

AnkA accumulates in the nuclei of infected HL-60 cells.

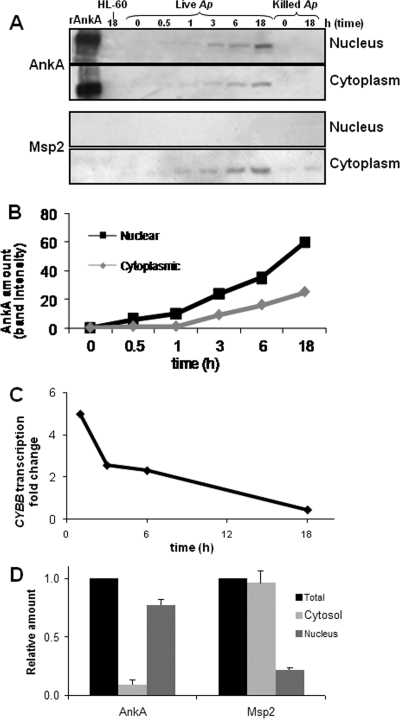

To study the kinetics of A. phagocytophilum AnkA accumulation in the nuclei of HL-60 cells and neutrophils, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of infected cells were analyzed by immunoblotting using MAbs specific for AnkA and the immunodominant A. phagocytophilum membrane protein, Msp2, which is approximately 25 times more abundant (Fig. 1). Translocation of AnkA into host cell nuclei was evident as early as 3 h postinfection (Fig. 1A). Although the amount of AnkA protein detected in nuclei of infected cells was greater than that in the cytoplasmic fraction, AnkA was also detected in the host cell cytoplasm. AnkA is likely translocated from A. phagocytophilum-containing vacuoles or morulae into the host cytoplasm before being transported into the host cell nucleus. In contrast, Msp2 protein was detected in the cytoplasmic fraction but not in the nucleus (Fig. 1A), consistent with the intracytoplasmic location of the bacterial cells. Heat-killed bacteria did not produce AnkA, and only traces of Msp2 were detected, which did not increase with time. The rate of accumulation of AnkA in the nucleus with live infection was higher than that in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1B). As AnkA accumulated in nuclei of infected cells, CYBB transcription decreased (Fig. 1C). CYBB encodes cytochrome B-245 or the gp91phox component of phagocyte oxidase, a key host protein known to influence A. phagocytophilum survival. As in HL-60 cells, the amount of AnkA in the nuclear fraction of infected human neutrophils was significantly higher than that in the cytoplasm, while Msp2 was significantly more abundant in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 1D), confirming the relevance of these observations in the primary host cell type in humans.

FIG. 1.

AnkA accumulates in nuclei of infected granulocytes as host transcriptional changes associated with A. phagocytophilum infection occur. (A) HL-60 cells were exposed to live or heat-killed A. phagocytophilum, and samples of cells were collected at different time points, fractionated, and analyzed for the presence of AnkA or Msp2 proteins in the nuclear and cytosolic fractions. (B) The amounts of AnkA in nuclei and cytosol of infected HL-60 cells were calculated by densitometry of the AnkA bands (a representative example of more than three replicate experiments is shown). (C) CYBB transcription levels over time were quantitated by qRT-PCR normalized to ACTB. (D) Neutrophils infected in culture with A. phagocytophilum were collected at 24 h postinfection and fractionated; total cell lysate, nuclear extract, and cytoplasm were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and reacted with AnkA-specific MAb or Msp2 MAb; and densitometric analysis of the bands was performed. Protein amounts in each fraction were normalized to the amount present in the total cell lysate. Shown are the results of three densitometric determinations as means ± standard errors.

AnkA induces host transcriptional changes associated with A. phagocytophilum infection.

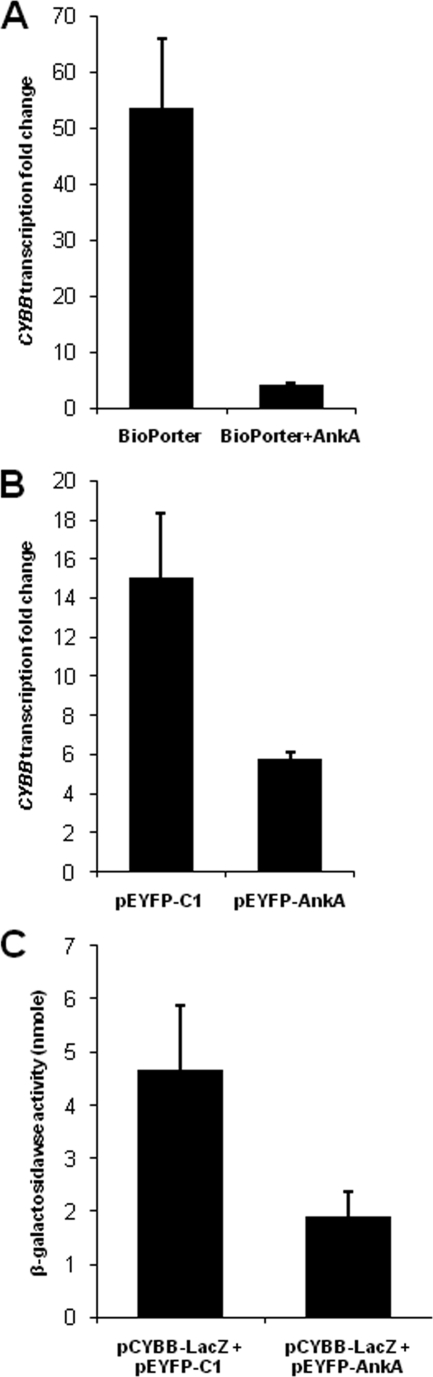

The presence of AnkA in the host cell nucleus when transcriptional changes occur and its ultrastructural association with host chromatin (9, 24) suggest a regulatory role for AnkA in host cell gene expression. To determine whether AnkA plays a role in the CYBB transcriptional changes observed during A. phagocytophilum infection, HL-60 cells were transfected with an AnkA mammalian expression plasmid (pEYFP-AnkA) or with purified rAnkA protein. While CYBB transcription was decreased with A. phagocytophilum infection, CYBB transcription was also silenced in HL-60 cells transfected with rAnkA compared to cells treated with the transfection reagent alone (Fig. 2A) and was significantly downregulated in HL-60 cells transfected with the AnkA-expressing plasmid pEYFP-AnkA (Fig. 2B). Since protein transfection efficiency is higher than plasmid transfection efficiency, these results are not directly comparable. This may also explain the relatively higher CYBB transcriptional reduction obtained with protein transfection. However, both transfection methods resulted in significant CYBB silencing.

FIG. 2.

Transfection of HL-60 cells with an AnkA-expressing plasmid or with purified rAnkA protein results in transcriptional changes characteristic of A. phagocytophilum infection. (A and B) Transcription levels of CYBB in HL-60 cells transfected with rAnkA protein (A) or with AnkA-expressing plasmid pEYFP-AnkA (B) were determined by quantitative qRT-PCR, with normalization to ACTB. Cells transfected with BioPORTER reagent alone (A) or with empty plasmid vector pEYFP-C1 (B) were used as controls. (C) HL-60 cells were cotransfected with the reporter plasmid pCYBB-LacZ and the pEYFP-AnkA for AnkA expression and compared to cells cotransfected with pCYBB-LacZ and the pEYFP plasmid control. β-Galactosidase activity was measured. All experiments were repeated three times and expressed as means ± standard errors. All comparisons were significant (P < 0.05; unpaired two-sided Student's t test).

These data indicate that AnkA could directly regulate expression of host CYBB. To confirm downregulation of CYBB by AnkA, a reporter plasmid containing the lacZ gene under the control of the CYBB promoter region from position −250 to +12 was cotransfected into HL-60 cells with the pEYFP-AnkA plasmid or with the pEYFP-C1 vector control. Expression of β-galactosidase using this plasmid was previously shown to be reduced with A. phagocytophilum infection (28). Here, cotransfection with the AnkA-expressing plasmid significantly reduced β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 2C). These experiments further confirm that the AnkA protein of A. phagocytophilum negatively regulates the CYBB promoter.

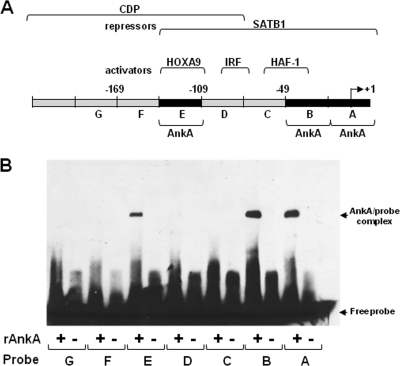

AnkA interacts with CYBB transcriptional regulatory regions.

To determine if AnkA directly interacts with the CYBB locus regulatory region, we used seven 30-bp probes spanning the CYBB proximal promoter region to identify specific AnkA binding sites by EMSA (Fig. 3). Even under stringent conditions, AnkA bound to the regions from bp −138 to −109 (probe E) and −48 to +12 (probes A and B). Binding of AnkA at the precise sites where transcriptional regulators also bind indicated a role for this bacterial protein in modulating host cell gene transcription. This raises the possibility that AnkA could affect CYBB transcriptional regulation by directly displacing transcriptional activators, by recruiting repressors, or by affecting chromatin structure around its DNA binding sites.

FIG. 3.

AnkA binds to sites in the CYBB proximal promoter. (A) Schematic representation of the CYBB proximal promoter and transcription factor binding sites. (B) Binding of rAnkA to seven 30-bp probes that span the CYBB promoter (bp −199 to +12bp) was assessed by EMSA. AnkA binding to probes A, B, and E resulted in shifted migration (AnkA/probe complex).

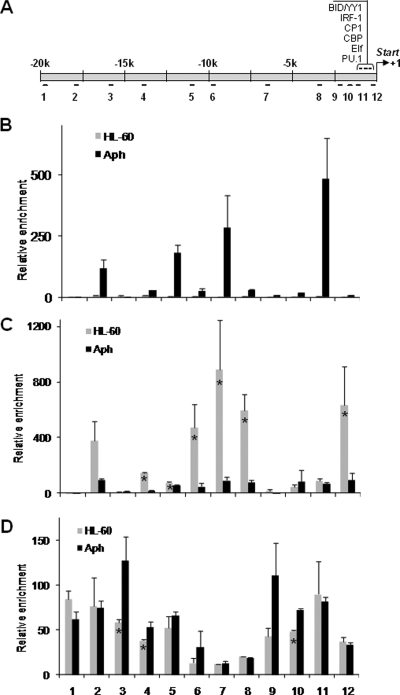

AnkA binds to multiple sites within the CYBB locus.

In addition to AnkA binding within the CYBB proximal promoter, we intended to identify other possible AnkA binding sites broadly over the CYBB locus. We used primer sets spanning approximately 20 kb upstream of the CYBB locus and ChIP to study a wider chromatin region (Fig. 4A). AnkA was found to bind to sites within the CYBB locus at and upstream of the proximal promoter region (Fig. 4B), consistent with the results obtained by EMSA.

FIG. 4.

A. phagocytophilum infection results in AnkA binding to the CYBB locus and changes in the host histone code. (A) Schematic representation of the CYBB promoter and upstream noncoding sequence. (B) AnkA-bound host DNA was immunoprecipitated by ChIP from A. phagocytophilum-infected (black bars) and uninfected (gray bars) HL-60 cells using a MAb against AnkA, and 12 primer sets were used to identify AnkA-bound DNA fragments within the CYBB locus by qPCR. Primer positions are indicated in panel A. (C and D) Histone 3 acetylation (C) and methylation (D) at the CYBB locus were also analyzed by ChIP. All experiments were repeated three times. Means ± standard errors are presented. Infected cells were harvested at 72 h post infection. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

A. phagocytophilum infection affects the histone code at the CYBB locus.

Changes in histone posttranslational modifications affect chromatin accessibility to transcriptional regulatory factors and could contribute to A. phagocytophilum downregulation of CYBB gene expression. To identify changes in host chromatin structure associated with A. phagocytophilum infection and AnkA binding, ChIP was used to study alterations in histone acetylation and methylation at the CYBB locus (Fig. 4C and D). After formaldehyde cross-linking of DNA and proteins, infected and uninfected cells were harvested and disrupted by sonication. Antibodies specific for histone H3 acetylated at Lys9 and Lys14 (Ac-H3) or methylated at Lys9 (Me-H3) were used. A dramatic decrease in Ac-H3 was observed at the CYBB locus in chromatin from infected cells (Fig. 4C), while only a minimal increase in histone methylation was detected with infection (Fig. 4D).

AnkA affects host cell gene expression.

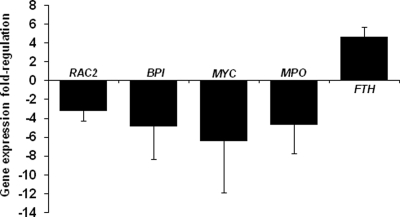

Binding of AnkA to multiple sites within the CYBB locus and the changes in chromatin structure associated with A. phagocytophilum infection suggest that AnkA could be involved in the global regulation of other differentially expressed defense genes. HL-60 cells transfected with the AnkA mammalian expression plasmid pEYFP-AnkA showed decreased expression of other genes known to be downregulated during A. phagocytophilum infection (Fig. 5). Transcription of RAC2, MPO, BPI, and MYC was significantly decreased with AnkA expression, whereas transcription of FTH was increased (Fig. 5), findings nearly identical to those with A. phagocytophilum infection alone (7). Although direct interactions of AnkA with these loci have not been demonstrated, the fact that their expression is reduced with AnkA transfection suggests that this protein likely functions by a mechanism that affects the expression of multiple host genes.

FIG. 5.

A. phagocytophilum AnkA expression in transfected cells results in changes in expression of host genes known to be affected by A. phagocytophilum infection. HL-60 cells were transfected with the AnkA-expressing plasmid pEYFP-AnkA using nucleofection technology. Expression of RAC2, BPI, MPO, MYC, and FTH in transfected cells was measured by qRT-PCR, normalized to ACTB, and expressed as fold change with respect to control cells transfected with the pEYFP-C1 vector control. Positive numbers indicate upregulation of expression after AnkA transfection, and negative numbers indicate downregulated expression. All experiments were repeated three times, and results are expressed as means ± standard errors. RAC2, small GTP binding protein, component of phagocyte oxidase; BPI, bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein; MPO, myeloperoxidase; MYC, v-myc viral oncogene involved in cell cycle progression; FTH, ferritin heavy chain.

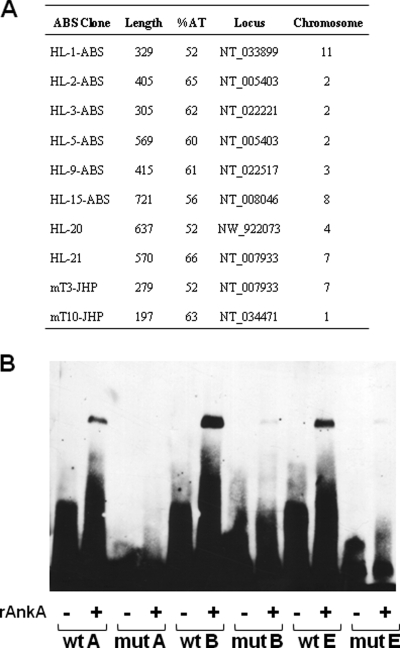

AnkA binds ATC-rich regions of the host genome.

A number of AnkA binding sites are present in host genomic DNA (24). To identify other binding sites and to establish their identity, we performed ChIP after nuclear protein-DNA cross-linking in A. phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells. After immunoprecipitation of AnkA-interacting DNA and amplification by LM-PCR, the recovered DNA was cloned and sequenced. All sequences identified were within intergenic regions, and none were detected more than once, suggesting that the critical binding feature may not be directly related to the primary nucleotide sequence (Fig. 6A). Further analysis of AnkA-bound DNA revealed that most sequences were ATC enriched on single strands, a feature commonly found in regulatory regions of chromatin where matrix attachment proteins bind. Out of 10 AnkA binding sites analyzed, 8 contained ATC-rich sequences (Fig. 6A). Two AnkA-bound DNA sequences identified in a previous study conducted in our laboratory (24) also contained ATC-rich sequences.

FIG. 6.

AnkA binds to ATC-rich sequences of the host chromatin. (A) AnkA-bound DNA was immunoprecipitated using an AnkA-specific MAb, cloned by LM-PCR, and sequenced. Sequences mT3-JHP and mT10-JHP were previously obtained in our laboratory (24). Infected cells were harvested at 72 h postinfection. (B) Binding of AnkA to the wild-type CYBB promoter probes A, B, and E, but not to mutated versions, was demonstrated by EMSA. The wild-type and mutated probes were incubated with rAnkA. Control reactions with no protein added were included as controls.

To confirm AnkA binding to ATC-rich DNA, AT stretches within the AnkA binding sites identified in the CYBB promoter were mutated (Fig. 6B). Purified rAnkA bound to the wild-type CYBB promoter probes in vitro (Fig. 6B). In contrast, the mobility of mutated forms of the probes was not affected by AnkA, showing the specificity of AnkA DNA binding (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these data suggest that AnkA repression of CYBB gene expression occurs by a mechanism similar to that used by the special AT-rich sequence binding protein 1 (SATB1), which binds to the secondary structure in ATC-rich sequences and induces changes in chromatin that result in transcriptional CYBB silencing.

DISCUSSION

The tick-transmitted rickettsia A. phagocytophilum, the causative agent of human granulocytic anaplasmosis, is one of only four bacteria known to survive and propagate within human neutrophils and their bone marrow progenitors. Neutrophils are unsuitable host cells for intracellular bacteria because they are short lived and, as primary defense cells, are equipped with diverse antimicrobial mechanisms. However, A. phagocytophilum interferes with the host's antimicrobial response through multiple mechanisms. It suppresses the early antimicrobial response by directly inhibiting antimicrobial functions. For instance, A. phagocytophilum detoxifies the oxidative burst triggered by infection by using its own superoxide dismutase enzyme and by inhibiting phagocyte oxidase assembly (6). A. phagocytophilum also alters other neutrophil physiological processes such as apoptosis, degranulation, phagocytosis, and inflammatory response. A. phagocytophilum directly interacts with signal transduction pathways, contributing to a dysregulated phenotype of the infected cell (16). However, as apoptosis of infected neutrophils is delayed by 24 h or longer, sustained neutrophil functional changes with A. phagocytophilum infection likely require altered expression of essential genes such as CYBB, RAC2, BPI, and MPO. Studies of global host cell gene transcription support these observations, as clusters of genes are differentially expressed in A. phagocytophilum-infected granulocytes (3, 11, 25).

Given metabolic and genomic resources thousands of times more limited than those of the host cell, A. phagocytophilum and other small genome intracellular bacteria require highly efficient mechanisms for survival and persistence. The data presented here demonstrate that A. phagocytophilum AnkA is an effector sufficient to induce some of the transcriptional changes observed in HL-60 cells during infection. AnkA binds regulatory regions of the host chromatin with properties similar to those of eukaryotic nuclear base unpairing region (BUR) binding proteins such as SATB1 and CDP (5). BUR binding proteins bind specialized regions dependent on DNA secondary structure and interact with or recruit proteins that modify chromatin architecture. These changes dramatically affect promoter accessibility to transcriptional activators, repressors, and histone-modifying proteins (e.g., acetylases, deacetylases, and methylases), such as with SATB1 and CDP, which interact with the promoter regions of CYBB and other genes and affect their transcriptional regulation (8). AnkA seems to play a similar role in CYBB regulation during A. phagocytophilum infection. Downregulation of CYBB expression with A. phagocytophilum infection is associated with decreased binding of transcriptional activators IRF-1 and PU.1 concurrent with increased binding of the CDP repressor to the CYBB promoter (28). Interestingly, our data and others have identified changes in protein binding to the CYBB promoter during A. phagocytophilum infection (28), which not only supports the interactions of AnkA with the locus we report here but could also reflect the presence of other A. phagocytophilum effectors in the host nucleus.

In this study, we show that AnkA from A. phagocytophilum also binds to the CYBB promoter and that AnkA is sufficient to regulate the expression of this gene. Although elucidation of the mechanism by which AnkA exerts transcriptional influence will require further investigation, interactions of AnkA with transcriptional regulatory regions could affect binding of transcriptional regulators to the promoters. AnkA also affects the epigenetic regulation of gene expression, such as with CYBB, perhaps by altering accessibility of these loci to chromatin-modifying enzymes, although a direct molecular link between histone modifications and AnkA presence remains to be demonstrated. However, the modifications of the histone code observed in the CYBB locus almost certainly result in chromatin condensation and silencing of gene expression, a mechanism exploited by other BUR binding proteins such as SATB1 (30). This hypothesis is also consistent with the preferential localization of AnkA to nuclear heterochromatin (9). BUR binding proteins such as SATB1 play an important role in cell differentiation by affecting chromatin structure and global gene transcription. SATB1 expression is silenced in differentiated leukocytes, derepressing the expression of CYBB and other SATB1-regulated genes. Due to the functional similarities of AnkA and SATB1, we speculate that AnkA may be playing a similar role to that of SATB1, downregulating expression of genes by affecting chromatin structure.

A clear understanding of the mechanisms for the translocation of AnkA from the bacteria to the host cell nucleus awaits further study, which will be facilitated with the recent successful genetic transformation of A. phagocytophilum (12). Other possible mechanisms for AnkA action within host cells also need investigation. AnkA phosphorylation and interactions with host cell cytoplasmic kinases were recently shown (15), although its role in regulating host cell function and gene expression remains unclear. Additional bacterial nuclear effectors will likely be identified as investigations become increasingly focused on host-pathogen interactions mediated by effector molecules at the nuclear interface. The data presented here provide evidence that AnkA acts as a nuclear effector that modifies host cell gene transcription and phenotype by directly binding to host chromatin. The data further strongly support the hypothesis that AnkA binds to heterochromatin in regions that play a role in chromatin remodeling and regulation of gene expression, a newly proposed mechanism for control of eukaryotic host cell function that could be broadly exploited by intracellular bacteria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH research grant R01-AI44102 to J.S.D. from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. A.M.M. was supported by a Pediatric Infectious Disease Society Fellowship Award funded by an educational grant from AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals.

We thank Dennis J. Grab and Terumi Kohwi-Shigematsu for fruitful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript and Nicole Barat and Danielle Large for technical assistance. Erol Fikrig, Yale University, kindly provided the reporter plasmid.

We declare that we have no competing financial interests.

J.C.G.-G. designed and did most of the experiments and prepared the manuscript, K.E.R.-B. and S.P. helped to demonstrate AnkA binding to the CYBB promoter by EMSA, A.M.M. was involved in the protein transfection studies, and J.S.D. helped analyze data and interpret results and supervised all studies. All authors contributed to discussions and manuscript preparation.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 March 2009.

Supplemental material for this article is available at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alto, N. M., F. Shao, C. S. Lazar, R. L. Brost, G. Chua, S. Mattoo, S. A. McMahon, P. Ghosh, T. R. Hughes, C. Boone, and J. E. Dixon. 2006. Identification of a bacterial type III effector family with G protein mimicry functions. Cell 124133-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbibe, L., D. W. Kim, E. Batsche, T. Pedron, B. Mateescu, C. Muchardt, C. Parsot, and P. J. Sansonetti. 2007. An injected bacterial effector targets chromatin access for transcription factor NF-kappaB to alter transcription of host genes involved in immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 847-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borjesson, D. L., S. D. Kobayashi, A. R. Whitney, J. M. Voyich, C. M. Argue, and F. R. Deleo. 2005. Insights into pathogen immune evasion mechanisms: Anaplasma phagocytophilum fails to induce an apoptosis differentiation program in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 1746364-6372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant, P. A., D. Venter, R. Robins-Browne, and N. Curtis. 2004. Chips with everything: DNA microarrays in infectious diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4100-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai, S. T., H. J. Han, and T. Kohwi-Shigematsu. 2003. Tissue-specific nuclear architecture and gene expession regulated by SATB1. Nat. Genet. 3442-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlyon, J. A., D. Abdel-Latif, M. Pypaert, P. Lacy, and E. Fikrig. 2004. Anaplasma phagocytophilum utilizes multiple host evasion mechanisms to thwart NADPH oxidase-mediated killing during neutrophil infection. Infect. Immun. 724772-4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlyon, J. A., W. T. Chan, J. Galan, D. Roos, and E. Fikrig. 2002. Repression of rac2 mRNA expression by Anaplasma phagocytophila is essential to the inhibition of superoxide production and bacterial proliferation. J. Immunol. 1697009-7018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catt, D., S. Hawkins, A. Roman, W. Luo, and D. G. Skalnik. 1999. Overexpression of CCAAT displacement protein represses the promiscuously active proximal gp91(phox) promoter. Blood 943151-3160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caturegli, P., K. M. Asanovich, J. J. Walls, J. S. Bakken, J. E. Madigan, V. L. Popov, and J. S. Dumler. 2000. ankA: an Ehrlichia phagocytophila group gene encoding a cytoplasmic protein antigen with ankyrin repeats. Infect. Immun. 685277-5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi, K. S., J. Garyu, J. Park, and J. S. Dumler. 2003. Diminished adhesion of Anaplasma phagocytophilum-infected neutrophils to endothelial cells is associated with reduced expression of leukocyte surface selectin. Infect. Immun. 714586-4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de la Fuente, J., P. Ayoubi, E. F. Blouin, C. Almazan, V. Naranjo, and K. M. Kocan. 2005. Gene expression profiling of human promyelocytic cells in response to infection with Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Cell. Microbiol. 7549-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felsheim, R. F., M. J. Herron, C. M. Nelson, N. Y. Burkhardt, A. F. Barbet, T. J. Kurtti, and U. G. Munderloh. 2006. Transformation of Anaplasma phagocytophilum. BMC Biotechnol. 642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galan, J. E., and P. Cossart. 2005. Host-pathogen interactions: a diversity of themes, a variety of molecular machines. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 81-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman, J. L., C. Nelson, B. Vitale, J. E. Madigan, J. S. Dumler, T. J. Kurtti, and U. G. Munderloh. 1996. Direct cultivation of the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 334209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ijdo, J. W., A. C. Carlson, and E. L. Kennedy. 2007. Anaplasma phagocytophilum AnkA is tyrosine-phosphorylated at EPIYA motifs and recruits SHP-1 during early infection. Cell. Microbiol. 91284-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, H. Y., and Y. Rikihisa. 2002. Roles of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, NF-kappa B, and protein kinase C in proinflammatory cytokine mRNA expression by human peripheral blood leukocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils in response to Anaplasma phagocytophila. Infect. Immun. 704132-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lara-Tejero, M., and J. E. Galan. 2002. Cytolethal distending toxin: limited damage as a strategy to modulate cellular functions. Trends Microbiol. 10147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin, M., A. den Dulk-Ras, P. J. Hooykaas, and Y. Rikihisa. 2007. Anaplasma phagocytophilum AnkA secreted by type IV secretion system is tyrosine phosphorylated by Abl-1 to facilitate infection. Cell. Microbiol. 92644-2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munter, S., M. Way, and F. Frischknecht. 2006. Signaling during pathogen infection. Sci. STKE 2006re5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagai, H., and C. R. Roy. 2003. Show me the substrates: modulation of host cell function by type IV secretion systems. Cell. Microbiol. 5373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niu, H., Y. Rikihisa, M. Yamaguchi, and N. Ohashi. 2006. Differential expression of VirB9 and VirB6 during the life cycle of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in human leucocytes is associated with differential binding and avoidance of lysosome pathway. Cell. Microbiol. 8523-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pak, J. W., and K. W. Jeon. 1997. A symbiont-produced protein and bacterial symbiosis in Amoeba proteus. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 44614-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan, X., A. Luhrmann, A. Satoh, M. A. Laskowski-Arce, and C. R. Roy. 2008. Ankyrin repeat proteins comprise a diverse family of bacterial type IV effectors. Science 3201651-1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park, J., K. J. Kim, K. S. Choi, D. J. Grab, and J. S. Dumler. 2004. Anaplasma phagocytophilum AnkA binds to granulocyte DNA and nuclear proteins. Cell. Microbiol. 6743-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedra, J. H., B. Sukumaran, J. A. Carlyon, N. Berliner, and E. Fikrig. 2005. Modulation of NB4 promyelocytic leukemic cell machinery by Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Genomics 86365-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren, B., F. Robert, J. J. Wyrick, O. Aparicio, E. G. Jennings, I. Simon, J. Zeitlinger, J. Schreiber, N. Hannett, E. Kanin, T. L. Volkert, C. J. Wilson, S. P. Bell, and R. A. Young. 2000. Genome-wide location and function of DNA binding proteins. Science 2902306-2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnupf, P., D. A. Portnoy, and A. L. Decatur. 2006. Phosphorylation, ubiquitination and degradation of listeriolysin O in mammalian cells: role of the PEST-like sequence. Cell. Microbiol. 8353-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas, V., S. Samanta, C. Wu, N. Berliner, and E. Fikrig. 2005. Anaplasma phagocytophilum modulates gp91(phox) gene expression through altered interferon regulatory factor 1 and PU.1 levels and binding of CCAAT displacement protein. Infect. Immun. 73208-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Worby, C. A., and J. E. Dixon. 2006. Bacteria seize control by acetylating host proteins. Science 3121150-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yasui, D., M. Miyano, S. T. Cai, P. Varga-Weisz, and T. Kohwi-Shigematsu. 2002. SATB1 targets chromatin remodelling to regulate genes over long distances. Nature 419641-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.