Abstract

Induction of an antigenically broad and vigorous primary T-cell immune response by myeloid dendritic cells (DC) in blood and tissues could be important for an effective prophylactic or therapeutic vaccine to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). Here we show that a primary CD8+ T-cell response can be induced by HIV-1 peptide-loaded DC derived from blood monocytes of HIV-1-negative adults and neonates (moDC) and by Langerhans cells (LC) and interstitial, dermal-intestinal DC (idDC) derived from CD34+ stem cells of neonatal cord blood. Optimal priming of single-cell gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production by CD8+ T cells required CD4+ T cells and was broadly directed to multiple regions of Gag, Env, and Nef that corresponded to known and predicted major histocompatibility complex class I epitopes. Polyfunctional CD8+ T-cell responses, defined as single-cell production of more than one cytokine (IFN-γ, interleukin 2, or tumor necrosis factor alpha), chemokine (macrophage inhibitory factor 1β), or cytotoxic degranulation marker CD107a, were primed by moDC, LC, and idDC to HIV-1 Gag and reverse transcriptase epitopes, as well as to Epstein-Barr virus and influenza A virus epitopes. Thus, three major types of blood and tissue myeloid DC targeted by HIV-1, i.e., moDC, LC, and idDC, can prime multispecific, polyfunctional CD8+ T-cell responses to HIV-1 and other viral antigens.

Broadly reactive, high-magnitude CD8+ T-cell responses to the various proteins of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) are considered important in host control of infection and prevention of AIDS (11). The efficacy of prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines could therefore largely depend on their capacity to elicit primary CD8+ T-cell reactivity of high magnitude that is specific for multiple regions of the HIV-1 proteome. Because HIV-1 has restricted tropism for humans, it has been necessary to assess T-cell reactivity to this virus within the context of the complications of natural infection or in clinical trials of candidate vaccines. An alternative approach for determining the potential immunogenicity of HIV-1 that could be targeted for vaccine design is in vitro priming of naïve CD8+ T cells. Generating and expanding primary T-cell immune responses from naïve precursors in vitro had been difficult due to the stringent activation and costimulatory requirements (41, 55, 62). In recent years, however, priming of T-cell immunity to various types of antigens has been greatly augmented by use of myeloid dendritic cells (DC) and the requirement of DC maturation for optimal antigen processing and presentation (5, 7, 19, 25, 28, 33-35, 44, 45, 53, 54, 60). These DC-based approaches have revealed that T cells from adults and neonates have comparable capacities for mounting primary responses to cancer and viral antigens (52, 53).

Subsets of myeloid DC reside in tissues and blood, where they interact with viral pathogens such as HIV-1 and are potent inducers of primary antiviral T-cell immunity (50). Because of the difficulty in isolating these DC directly from blood and tissues, most studies of primary T-cell immunity have used myeloid DC derived in vitro from blood cell precursors. Monocyte-derived DC (moDC) are conventionally generated by stimulation of blood CD14+ monocytes with granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin 4 (IL-4) (51), whereas Langerhans cells (LC) and interstitial, dermal-intestinal DC (idDC) can be similarly generated from neonatal (8) or adult (48) CD34+ stem cells of blood. These subsets of myeloid DC are characterized by lack of expression of B-cell, T-cell, and natural killer cell lineage markers and expression of the alpha M integrin CD11b. They can be distinguished by expression of the type II lectin Langerin on LC and by the C-type lectin DC-specific ICAM 3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN) on idDC in vivo (59) and idDC generated in vitro from CD34+ stem cells (48). The importance of LC and idDC in HIV-1 immunopathogenesis is also indicated by their susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in vivo and in vitro (12, 13, 30, 58).

Little is known about the capacity of moDC, LC, and idDC to prime anti-HIV-1 T-cell immunity. This information is important for understanding the immunopathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. It is also of value for development of DC-based vaccines for immunotherapy of HIV-1 infection and for targeting of DC for prophylactic vaccines (49). In this study, we show that broadly reactive, primary responses can be induced in CD8+ T cells by moDC, LC, and idDC derived from HIV-1-negative adult and neonatal donors.

(Portions of this investigation are part of a dissertation submitted by Bonnie A. Colleton in partial fulfillment of requirements for the Ph.D. degree from the University of Pittsburgh.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of moDC, LC, and idDC.

Approval was obtained from the institutional review board prior to these studies involving human subjects. To obtain immature moDC, CD14+ monocytes were positively selected from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of healthy, HIV-1 negative, HLA A*0201 adult volunteers or from HLA A*0201 neonatal cord blood (Magee-Womens Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA) using anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody (MAb)-coated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) to a purity of >95%. High-resolution HLA molecular typing was done by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Tissue Typing Laboratory. The moDC were derived by culture of the purified blood monocytes with 1,000 U/ml recombinant GM-CSF (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) and 1,000 U/ml recombinant IL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) (24). Immature moDC were treated on day 5 with CD40L (0.5 μg/ml; Amgen or Alexis, San Diego, CA) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (1,000 U/ml; R&D) (16) or with a combination of inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), i.e., IL-1β (2 ng/ml; R&D), IL-6 (1,000 IU/ml; R&D), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (10 ng/ml; R&D), and PGE2 (5 μM; Pfizer, Vienna, Austria), for 40 h to induce DC maturation (27).

To obtain LC and idDC, mononuclear cells from neonatal cord blood samples were treated with anti-CD34 MAb-coated magnetic microbeads (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) to isolate CD34+ stem cells at a purity of >98% (48). The CD34+ cells were then preexpanded with thrombopoietin (50 ng/ml; R&D) in X-VIVO 15 medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) for generating LC or in complete Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated, human AB+ serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for generating idDC. The culture medium for both LC and idDC was supplemented with GM-CSF (1,000 IU/ml), TNF-α (5 ng/ml), c-kit ligand (20 ng/ml; R&D), and FLT-3 ligand (50 ng/ml; R&D). Following 24 h of incubation, the cells were washed and cultured in this medium in the absence of thrombopoietin. On day 5, the cells were washed and cultured in the same cytokines but without c-kit ligand and FLT-3 ligand. For the development of LC, transforming growth factor β1 (10 ng/ml; R&D) was added and left throughout the culture period. For the generation of idDC, IL-4 (500 IU/ml) was added on day 5 with GM-CSF and TNF-α. These immature LC and idDC were matured with the cytokine-PGE2 mixture as with the moDC. Phenotypic analysis by flow cytometry was done based on the methods of Ratzinger et al. (48) and Huang et al. (24), for DC markers CD11b (alpha M integrin), CD207 (Langerin), and CD209 (DC-SIGN). To detect monocytes and plasmacytoid DC, we stained for CD91 (alpha-2-macroglobulin receptor), and to assess DC maturation, we stained for CD83 (a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily and a regulator of T- and B-cell maturation). Immature moDC were harvested and stained after 5 days of culture with IL-4 and GM-CSF and after an additional 40 h of maturation. The immature and mature moDC were then stained with the MAbs listed above to determine their phenotype. Immature LC and idDC were phenotyped after the 10 days of culture with their respective differentiation media and matured for 40 h. Optimal photo multiplier tube voltage settings for each fluorescence channel were determined on the day of the experiment using Cytometer Setup and Tracking beads (BD Biosciences). These voltage values were set to give the lowest coefficient of variation for that individual fluorescence channel.

Synthetic peptides.

Fifteen-mer peptides overlapping by 11 amino acids spanning the entire sequence of HIV-1 DU422 Gag, HIV-1 consensus subtype B Env, and HIV-1 consensus subtype B Nef were provided by the NIH AIDS Research & Reference Reagent Program (Germantown, MD) and used in priming assays. HLA A*0201-restricted HIV-1 p1777-85 (SL9, SLYNTVATL), p1771-90 (GQ20, GSEELRSLYNTVATLYCVHQ), RT476-484 (IV9, ILKEPVHGV), p24151-159 (TV9, TLNAWVKVV), gp120192-200 (KV9, KLTSCNTSV), gp120311-320 (RI10, RGPGRAFVTI), and gp160813-822 (SV10, SLLNATDIAV); Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) BMLF1280-288 (GL9, GLCTLVAML); cytomegalovirus (CMV) pp65495-503 (NV9, NLVPMVATV); and influenza A virus (FLU) M158-66 (GL9, GILGFVFTL) were prepared by the Protein Research Lab, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL. A pool of 4 CMV, 15 EBV, and 12 FLU peptides representing a cross-section of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I dominant epitopes (10) was provided by the NIH AIDS Research & Reference Reagent Program.

In vitro priming and expansion of T cells.

For priming of the adult donor T cells, PBMC were obtained from the same HIV-1 negative, unrelated adult subjects used for deriving the DC. Autologous moDC matured with CD40L and IFN-γ (16, 23) were incubated with 50 μg/ml of peptides in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) for 2 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere (62). The DC were harvested and resuspended with autologous PBMC depleted of CD14+ monocytes (as described above) or CD8+ T cells using anti-CD8 MAb microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) where indicated, at a responder-to-stimulator (T-cell/DC) ratio of 10:1. The cocultures were fed with fresh RPMI 1640 medium with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Cellgro, Lawrence, KS) supplemented with recombinant IL-15 (2.5 ng/ml; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and IL-2 (50 U/ml; Chiron, Emeryville, CA) after 5 days and at 2- to 3-day intervals thereafter for 2 weeks. Two weeks following the first stimulation, T cells were restimulated with freshly matured autologous moDC loaded with the same set of peptides as in the primary stimulation by adding peptide-loaded DC directly to the T-cell-DC cocultures. T cells were harvested after a total of 28 days of culture and used directly in tetramer assays or enriched for CD8+ T cells by positive selection using anti-CD8 MAb microbeads for use in enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays.

The moDC, LC, and idDC generated from HLA A*0201 cord blood samples and matured with the cytokine-PGE2 mixture were used similarly in priming assays. Briefly, the mature DC subsets were loaded with 10 μg/ml of the peptides for 2 h and cocultured with autologous CD14− CD34− cells (responder T cells) at a ratio of 30 to 1. The CD14− CD34− cells were restimulated after 1 week. The cells were harvested after a total of 2 weeks of culture, phenotyped, and used in functional assays. In some experiments, CD8+ T cells were purified from the stimulated cell cultures using anti-CD8 magnetic beads as described above and examined for antigen-specific priming.

ELISPOT and cytotoxicity assays.

An ELISPOT assay modified from the AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol was used to determine the frequency of primed T cells capable of producing IFN-γ as previously described (23). Cytotoxicity was assessed by a 51Cr release assay using effector-to-target cell ratios of 40:1, 20:1, and 10:1 (25). The percentage of lysis was calculated as 100 × (experimental counts per minute − spontaneous counts per minute)/(maximum counts per minute − spontaneous counts per minute). Specific lysis was expressed as the percentage of lysis in peptide-treated targets minus the percentage of lysis in non-peptide-treated targets. T-cell responses that were greater than the mean plus two standard deviations of the responses to DC without peptide were considered positive.

Intracellular staining.

The CD14− CD34− cells, stimulated repetitively with two rounds by peptide-loaded moDC, LC, or idDC, were counted and incubated with costimulatory MAbs specific for CD28 and CD49d (1 μg/ml; BD Biosciences), monensin (5 μg/ml; Sigma), brefeldin A (5 μg/ml, Sigma), CD107a phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy5 (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA), and peptides (5 μg/ml). A negative control (without peptides) and a positive control (staphylococcal enterotoxin B) (1 μg/ml; Sigma) were included in each assay. Cells were then stained with MAb CD8 allophycocyanin (APC) Cy7 (APC Cy7), CD4-APC Cy7, and CD3-PE Cy7; fixed; permeabilized; and stained with IL-2-APC (Biolegend), IFN-γ-fluorescein isothiocyanate, and MIP1β-PE (all from BD PharMingen) and TNF-α-Pacific blue (eBioscience) as described by Betts et al. (2). Data were collected with an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Diego, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo 7.2.5 software (TreeStar).

Staining with peptide-MHC class I tetramers.

HLA A*0201 tetramers refolded around HIV-1 p1777-85 (SL9), EBV BMLF1280-288 (GL9), FLU M158-66 (GL9), and CMV pp65495-503 (NV9) were used to stain T cells that were stimulated by the peptide-loaded DC. In some experiments, the T cells were also surface stained with CD3-APC Cy7, CD8-Pacific blue, CD45 RA PE cyanin 7, CCR7-fluorescein isothiocyanate, CD27-PE (BD PharMingen), and tetramer-APC (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). After incubation and washing, cells were fixed and analyzed with an LSR II flow cytometer (BD).

Statistical analysis.

We used the Scheffe multiple comparison for variance analysis, and analysis of variance and the Student t test for comparisons between groups.

RESULTS

Optimal priming of antiviral CD8+ T cells requires mature DC and CD4+ T cells.

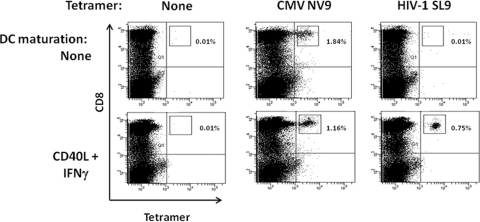

We have previously shown that CD40L-matured moDC are superior to immature DC in priming of CD8+ T cells to HIV-1 peptides and proteins (25). Moreover, we have also recently shown that moDC matured with CD40L and IFN-γ produce greater amounts of IL-12 than do CD40L-matured DC (16), which is important for activation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells (57). Therefore, in this study we first assessed adult donor moDC matured with CD40L and IFN-γ for their capacity to prime HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells compared to stimulation of recall, memory T cells to CMV in healthy, HIV-1-seronegative, CMV-seropositive HLA A*0201 subjects. We found that, as previously reported (18), these individuals had circulating CD8+ T cells positive for CMV NV9 by tetramer staining (e.g., 0.7% positive) (data not shown) and also were negative for HIV-1 SL9 (<0.01% positive). The levels of CMV NV9-specific CD8+ T cells increased after stimulation with mature moDC loaded with CMV NV9 (e.g., 5.7% by 21 days) (data not shown) and then decreased (e.g., 1.16% by 42 days) (Fig. 1). Moreover, immature moDC were as efficient as mature moDC in activating these T-cell recall responses to CMV (Fig. 1). Priming of CD8+ T cells with SL9-loaded, CD40L-IFN-γ-matured moDC resulted in peak responses by 4 to 6 weeks, ranging from 0.35% to 0.75% tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells. By comparison, stimulation of T cells with HIV-1 SL9-loaded, immature moDC resulted in minimal priming. Thus, in further studies of adult T-cell priming, we used CD40L- and IFN-γ-matured moDC as antigen-presenting cells and harvested the T cells after 4 weeks of antigen stimulation.

FIG. 1.

Priming of CD8+ T cells to HIV-1 SL9 peptide-loaded moDC matured with CD40L and IFN-γ. Day 5 adult moDC derived from HIV-1-seronegative, CMV-seropositive HLA A*0201 healthy donors were either left immature (upper row) or matured with CD40L and IFN-γ (lower row). The moDC were loaded with CMV NV9 (memory recall control), HIV-1 SL9, or no peptide and then cocultured with autologous PBMC for up to 6 weeks, with one restimulation at 2 weeks. Peptide-specific CD8+ T cells were detected by staining with their respective peptide-tetramer complexes. Data shown are from 42 days of peptide stimulation. The results are representative of data from one of two subjects.

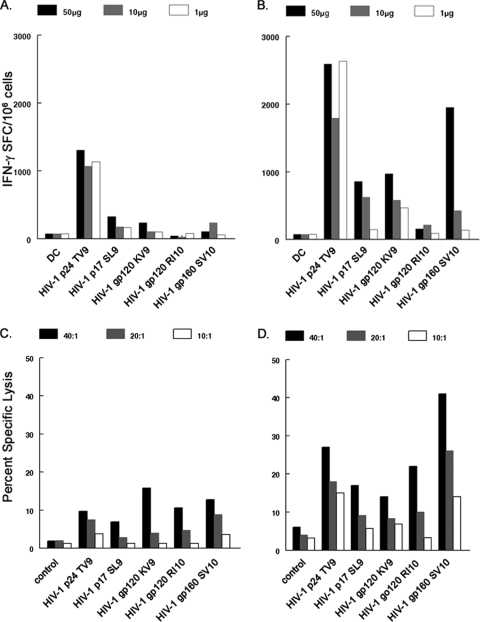

Previous studies have shown that CD4+ T cells are required for optimal CD8+ T-cell priming to antigen-loaded, neonatal LC (61). We therefore next examined whether adult DC matured with CD40L and IFN-γ required CD4+ T cells for optimal priming of antiviral CD8+ T cells. For this, mature moDC were loaded with five different HIV-1 peptides representing known immunodominant HLA A*0201 epitopes and cultured with purified CD8+ T cells or the CD8+ and CD4+ T cells at the CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratio as in their PBMC for the two rounds of primary stimulation. The greatest primary CD8+ T-cell responses were consistently observed in the cultures containing CD4+ T cells as determined by both IFN-γ production (Fig. 2A and B) and lytic activity (Fig. 2C and D). T-cell responses were detected against all five HIV-1 peptides in both assays when CD4+ T cells were present during the priming, with the greatest reactivity to Gag TV9 and Env SV10. Thus, CD4+ T cells enhanced the priming of adult donor anti-HIV-1 CD8+ T cells by mature DC, as has previously been demonstrated for priming of neonatal CD8+ T cells (61). We therefore included autologous CD4+ T cells in all subsequent priming experiments.

FIG. 2.

CD4+ T cells are required for optimal CD8+ T-cell priming to antigen-loaded DC. Mature moDC isolated from HIV-1 naïve HLA A*0201 donors were loaded with 50, 10, or 1 μg/ml of peptides representing known HIV-1 epitopes. The peptide-loaded moDC were used to prime autologous CD8+ T cells alone (A) and autologous CD8+ and CD4+ T cells at ratios equal to that of their PBMC (B). The CD8+ T cells were then purified with anti-CD8 MAb beads (see Materials and Methods) and assessed in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. T cells stimulated with DC not loaded with peptide were used as negative controls. Cytotoxicity was assessed by 51Cr release assay using primed CD8+ T cells (C) and CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (D) as effectors and peptide-loaded, autologous B lymphoblastoid cell lines as targets at effector-to-target ratios of 40:1, 20:1, and 10:1, and the percent specific lysis was calculated. The results are representative of data from one of two subjects. SFC, spot-forming cells. Cytotoxicity control, untreated autologous B lymphoblastoid cell lines.

Priming of antiviral CD8+ T cells by neonatal cord blood moDC, LC, and idDC.

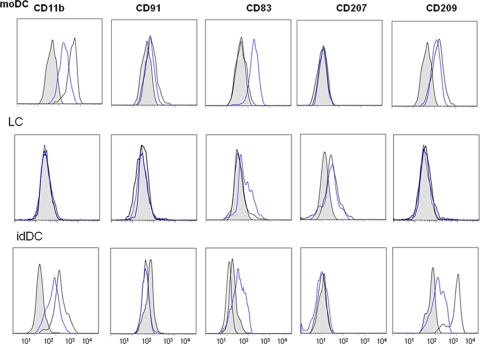

We next determined the capacity of neonatal cord blood moDC, LC, and idDC to prime CD8+ T cells to viral peptides as shown by ELISPOT assay for single cell, antigen-specific IFN-γ production. We first confirmed the phenotypes of the moDC, LC, and idDC by differential expression of several markers (Fig. 3). Only moDC and idDC expressed alpha M integrin CD11b, as reported by Ratzinger et al. (48), whereas only moDC expressed CD91, which is the low-density lipoprotein-related protein 1 (alpha-2-macroglobulin receptor) present on monocyte-lineage cells (21). The LC were negative for CD209 (DC-SIGN), which was expressed only by idDC and moDC. Similar to the results described by Ratzinger et al. (48), LC but not moDC or idDC expressed CD207 (Langerin). Maturation increased expression of CD83 on all three types of DC and decreased expression of CD209 on moDC and idDC (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Phenotypic identification of moDC, LC, and idDC derived from CD34+ cells of cord blood. The CD34+ cord blood cells were grown as described in Materials and Methods and either left immature (black line, open figure) or matured with the cytokine-PGE2 cocktail for 40 h (blue line, open figure). The shaded figures represent the respective isotype controls. Data are representative of one of five subjects.

We next found that neonatal CD8+ T-cell responses could be primed to five different 9-mer or 20-mer peptides derived from HIV-1 Gag and reverse transcriptase, as well as EBV and FLU, when presented by either moDC, LC, or idDC. As expected, CD8+ T cells taken directly from the cord blood did not produce IFN-γ in response to any type of DC loaded with the viral peptide pool (Fig. 4A, S0). However, CD8+ T cells specific for the antigen pool were detected after a single round of stimulation with antigen-loaded DC, which increased in number after two rounds of stimulation (Fig. 4A, S1 and S2, respectively). Compared to S1, there was greater T-cell reactivity primed after S2 in response to peptide pool-loaded moDC (P = 0.05) and LC (P < 0.05) but not idDC (P = not significant). To further define the antigen specificity of the priming, we determined the number of CD8+ T cells primed to produce IFN-γ to the different viral antigens after stimulation for 2 weeks with the peptide pool-loaded DC. The moDC and LC primed greater numbers of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells specific for FLU GL9 than did the idDC (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). Similarly, LC primed more CD8+ T cells specific for HIV-1 SL9 than did the idDC (P < 0.05).

FIG. 4.

Priming of CD8+ T cells isolated from HLA A*0201 cord blood by autologous DC loaded with viral peptides. (A) The moDC, LC, and idDC were isolated from four HLA A*0201 cord blood samples, matured with the cytokine-PGE2 mixture for 40 h, and loaded with a pool of five HLA A*0201 peptides (HIV-1 SL9, GQ20, and IV9; EBV GL9; and FLU GL9). These antigen-loaded DC were used to stimulate purified CD8+ T cells from autologous cord blood mononuclear cells in the ELISPOT assay (S0). Also, cord blood mononuclear cells were stimulated with these peptide-loaded DC for 1 week (S1) or 2 weeks (S2), from which CD8+ T cells were purified and assessed for IFN-γ production in the ELISPOT assay in response to DC loaded with the same peptide pool. (B) Purified CD8+ T cells derived from the four HLA A*0201 cord blood mononuclear samples that were stimulated for two sequential rounds (i.e., S2) with the different DC subsets loaded with the five-peptide pool were assessed for IFN-γ production in an overnight ELISPOT assay with the different DC subsets loaded separately with each single peptide. SFC, spot-forming cells. Data are means + standard errors.

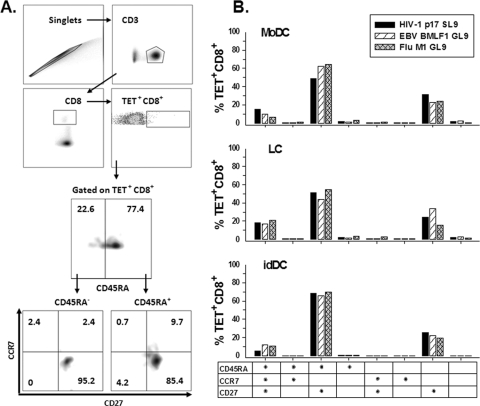

We examined the T-cell phenotype of the primed neonatal CD8+ T cells by staining with peptide-complexed tetramers for HIV-1 SL9, EBV GL9, and FLU GL9 and MAbs specific for naïve and memory T-cell markers. There is currently no consensus on the surface markers that differentiate memory T cells (1). Therefore, for the purposes of this in vitro priming model, we defined major populations of T cells based on expression of CD45RA, CCR7, and CD27. The flow cytometry gating strategy for defining the T-cell subpopulations is shown in Fig. 5A. We found that there were predominately three phenotypes of CD8+ T cells specific for the three viral peptides in the primed cultures generated in response to the three types of DC. The greatest subpopulation was CD45RA+ CCR7− CD27+, i.e., 49 to 68% for HIV-1 SL9, 44 to 66% for EBV GL9, and 55 to 70% for FLU GL9, with the highest levels of these CD8+ T cells being induced by idDC (Fig. 5B). The second most prominent subpopulation was CD45RA− CCR7− CD27+, i.e., 24 to 31% for HIV-1 SL9, 22 to 34% for EBV GL9, and 16 to 22% for FLU GL9, with the lowest levels of these CD8+ T cells being induced by idDC. These phenotypes are within antigen-experienced subsets in the CD8+ T-cell differentiation pathway (1). The third subpopulation was naïve CD45RA+ CCR7+ CD27+ cells, i.e., 6 to 19% HIV-1 SL9, 10 to 17% EBV GL9, and 7 to 21% FLU GL9, with similar levels present in the cultures stimulated by the three types of DC. All other peptide-specific CD8+ T-cell subpopulations were <3.5% of the total tetramer-positive cells (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Virus peptide-specific, CD8+ T-cell phenotypes primed by the peptide-loaded DC. Neonatal cord blood T cells were primed with autologous moDC, LC, or idDC that were loaded with HIV-1 p1777-85 (SL9), EBV BMLF1280-288 (GL9), or FLU M158-66 (GL9). (A) Representative plots showing the gating strategy used to define lymphocytes stimulated with moDC loaded with FLU GL9 peptide, based on height and area forward-scatter measurement, and CD8+ T lymphocytes based on the expression of CD3 and CD8. Tetramer-positive (Tet+) cells are a subset of the CD8+ cells. Gating regions were set based upon the fluorescence of the negative control sample. (B) Percent CD45RA, CCR7, and CD27 expression on tetramer-positive CD8+ T lymphocytes. The results are calculated as the overall gate frequency based on the gating strategy and parental T-cell frequencies shown in panel A. These results are representative data from one of two subjects.

Priming of polyfunctional CD8+ T cells by DC.

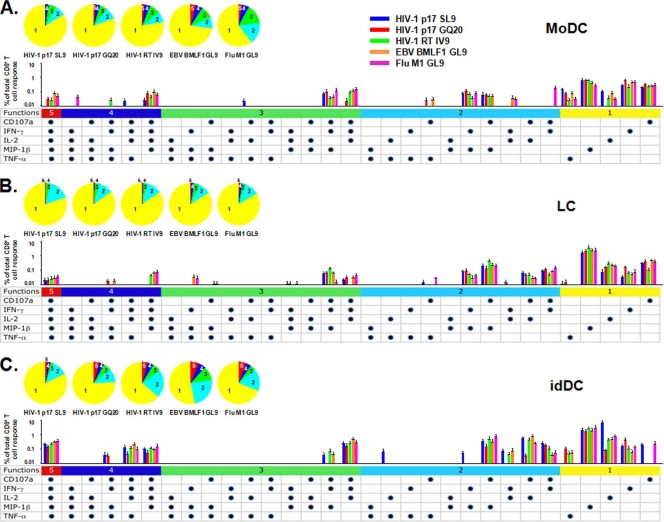

We next examined the DC-primed CD8+ T cells for polyfunctional activity, i.e., production of more than one cytokine, chemokine, or cytotoxic marker, to HIV-1 and other 9-mer viral peptides, i.e., HIV-1 SL9 and IV9, EBV GL9, and FLU GL9. To examine the effects of proteolytic processing by DC on priming of the T cells, we included a 20-mer (GQ20) with N- and C-terminal extensions of the SL9 epitope. We found that all three subsets of neonatal DC primed a large number of polyfunctional CD8+ T cells to HIV-1 SL9, and GQ20, as well as to HIV-1 IV9, EBV GL9, and FLU GL9 peptides (Fig. 6). Thus, CD8+ T cells primed by moDC, LC, and idDC loaded with these HIV-1, EBV, and FLU peptides produced all five of the immunologic mediators, i.e., CD107a, IFN-γ, IL-2, MIP-1β, and TNF-α (P = not significant for moDC versus LC versus idDC). The percentage of polyfunctional T cells producing a combination of four of the five immune mediators, i.e., CD107a, IFN-γ, IL-2, and MIP-1β, was also prominent in response to most of the viral peptides presented by the three types of DC. The idDC loaded with any of the five peptides also stimulated high levels of CD107a, IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α. Indeed, polyfunctional T cells producing combinations of two to five of these immune mediators specific for these five viral peptides were greatest for idDC compared to moDC or LC (Fig. 6). Polyfunctional T cells producing three immune mediators were notable for CD107a, IFN-γ, and IL-2 and for CD107a, IFN-γ and TNF-α in response to most of the viral peptides presented by all three types of DC. Distinctive patterns of polyfunctional T cells producing two immune mediators were apparent for CD107a and IL-2, and for CD107a and IFN-γ, stimulated by LC and idDC for the five peptides, with few or no such T cells primed in response to moDC. All three DC subsets primed T cells for combined CD107a and MIP-1β production specific for most of the viral peptides.

FIG. 6.

Primary polyfunctional CD8+ T-cell reactivity to five viral peptides induced by moDC, LC, and idDC. Data are means + standard errors from four HLA A*0201 cord blood samples. The iDC induced greater T-cell priming than moDC or LC for two immune mediators in response to HIV-1 SL9 (P = 0.01) and greater than moDC for HIV-1 GQ20 and IV9 (P < 0.05). The iDC induced greater T-cell priming than LC for three immune mediators in response to HIV-1 SL9 (P = 0.04) and for four immune mediators in response to HIV-1 SL9 and GQ20 (P = 0.03). The five peptides primed more four- and five-immune-mediator combinations than the three other marker combinations (P < 0.04). All of the peptides except FLU GL9 primed more three-, four-, and five-marker combinations than the two other immune mediator combinations (P < 0.05). HIV-1 SL9, EBV GL9, and FLU GL9 primed more two-, three-, four-, and five-immune-mediator combinations than the monofunctional immune mediator responses (P < 0.05).

Finally, monofunctional T cells were prominent for MIP-1β, IFN-γ, or IL-2 in response to the five peptides stimulated by the three DC subsets. Of note was that a substantial TNF-α response was primed in response to the five viral peptides loaded into moDC and idDC, but only at very low levels to the 20-mer peptide, HIV-1 GQ20, presented by the LC. Similar restricted T-cell priming was found for CD107a production specific for HIV-1 SL9 and FLU GL9 that was induced by idDC.

Taken together, these results indicate that substantial numbers of polyfunctional as well as monofunctional neonatal CD8+ T cells can be primed by moDC, LC, and idDC. Among these DC, the idDC induced the greatest levels of polyfunctional CD8+ T-cell reactivity.

Multispecificity of primary T-cell responses induced by DC.

We next explored the antigenic breadth of the immunogenicity of moDC loaded with overlapping 15-mer peptides for Gag, Env, and Nef derived from consensus strains of HIV-1. Because of limited numbers of neonatal cord blood DC, we focused on our model of T-cell priming using adult donor moDC. The cells were tested for immunogenicity using the single-cell IFN-γ ELISPOT response to Gag, Env, and Nef for two unrelated HIV-1-seronegative subjects matched at HLA A*0201, HLA B*1501, and HLA DRB4*0103. Combined data from two priming experiments on these two subjects show that there was a primary T-cell response to several known epitopes for the MHC class I alleles expressed by these subjects within the 15-mers of the three HIV-1 proteins (Table 1). Overall, we noted primary T-cell reactivity to 15-mers containing known epitopes for 2 Gag p17, 10 Gag p24, 1 Gag p1, 6 Env gp120, 8 Env p41, and 15 Nef regions. Of these, there was a common response between the two unrelated subjects to one epitope each for Gag p24, Env gp120, and Env gp41 and two for Nef. We did not detect primary T-cell responses containing known MHC class II epitopes within these HIV-1 15-mers.

TABLE 1.

Primary T-cell reactivity to known MHC class I epitopes of HIV-1 Gag, Env, and Nefa

| HIV-1 protein | Position | Sequence | Known epitope with matching allele(s)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gag (p17) | 18-26 | KIRLRPGGK | A*0301 |

| 77-85 | SLYNTVATL | A*0201 | |

| Gag 141-150 (p24) | 9-18 | QMVHQAISPR | A*0301(A3 supertype) |

| Gag 142-150 | 10-18 | MVHQAISPR | A*0301(A3 supertype) |

| Gag 151-159 | 19-27 | TLNAWVKVI | A*0201 |

| Gag 210-218 | 78-86 | AEWDRLHPV | A2c |

| Gag 260-267 | 128-135 | DIYKRWII | B*0801 |

| Gag 267-274 | 135-142 | ILGLNKIV | A*0201 |

| Gag 269-277 | 137-145 | GLNKIVRMY | B*1501 |

| Gag 291-300 | 159-168 | EPFRDYVDRF | A*0201 |

| Gag 296-304 | 164-172 | YVDRFFKTL | Cw*0304 |

| Gag 327-334 | 195-202 | NPDCKTIL | B*0801 |

| Gag 433-442 (p1) | 1-10 | FLGKIWPSHK | A*0201 |

| Env gp120 | 33-42 | KLWVTVYYGV | A*0201 |

| 34-42 | LWVTVYYGV | A*0201 | |

| 103-111 | QMHEDIISL | A*0201c | |

| 108-116 | IISLWDQSL | A*0201 | |

| 121-129 | KLTPLCVTL | A*0201 | |

| 217-226 | YCAPAGFAIL | Cw*0102 | |

| Env gp41 | 46-54 | RAIEAQQHL | Cw*0304, B*1501 |

| 72-81 | VERYLKDQQL | A*0201 | |

| 73-81 | ERYLKDQQL | B*0801 | |

| 75-82 | YLKDQQLL | B*0801 | |

| 167-175 | WLWYIKIFI | A*0201c | |

| 276-284 | RRGWEVLKY | A*0101 | |

| 288-296 | LLQYWSQEL | A*0201 | |

| 303-311 | LLNATAIAV | A*0201 | |

| Nef | 13-20 | WPTVRERM | B*0801 |

| 13-27 | WPTVRERMRRAEPAA | A*0201 | |

| 66-74 | VGFPVRPQV | A*0201 | |

| 73-82 | QVPLRPMTYK | A*0301 | |

| 77-92 | RPMTYKAAVDLSHFLK | A*0201 | |

| 84-92 | AVDLSHFLK | A*0301 | |

| 86-94 | DLSHFLKEK | A*0301 | |

| 90-97 | FLKEKGGL | B*0801 | |

| 85-100 | VDLSHFLKEKGGLEGL | A*0201c | |

| 109-117 | ILDLWVYHT | A*0201 | |

| 117-127 | TQGYFPDWQNY | B*1501 | |

| 121-135 | FPDWQNYTPGPGIRY | A*0201 | |

| 125-139 | QNYTPGPGIRYPLTF | A*0201 | |

| 137-145 | LTFGWCFKL | A*0201c | |

| 181-195 | LEWKFDSRLAFHHMA | A*0201 |

MHC class I epitopes included in this table were defined by the HIV sequence database based on being well-defined optimal epitopes or based on binding affinity, T-cell receptor usage, computational epitope prediction, or functional studies using samples from subjects with the corresponding allele. The data shown are combined from two separate priming experiments on two HIV-1-negative normal subjects.

The HLA haplotypes were as follows: for subject 1, HLA A*0201 A*0101 B*1501 B*1302 Cw*0102; DRB1*0701/DRB1*0901 DQB1*0202/DQB1*0303 DRB4*0103, and for subject 2, HLA A*0201 A*0301 B*1501 B*0801 Cw*0304; DRB1*0301/DRB1*0401 DQB1*0201/DQB1*0302 DRB3*0101/DRB4*0103.

Common T-cell response associated with shared MHC class I alleles between the two subjects.

To assess further the specificity of these primary responses, we deduced the optimal MHC class I and II epitopes from the consensus 15-mers in the Los Alamos HIV Immunology Database for potential epitopes to Gag, Env, and Nef. Potential MHC class I and II epitopes were defined based on C-terminal and N-terminal anchor residues matching one or more motifs associated with respective MHC class I or II alleles. This revealed a broad reactivity to potential MHC class I and II epitopes within the 15-mers of the three HIV-1 proteins (data not shown). Overall, we primed T-cell responses in the two subjects to a total of 201 potential MHC class I epitopes (HLA A, B, and C; 23 Gag p17, 18 Gag p24, 80 Env gp120, 36 Env gp41, and 26 Nef) and 109 potential MHC class II epitopes (HLA DR and DQ; 10 Gag p17, 17 Gag p24, 46 Env gp120, 26 Env gp41, and 10 Nef). These data suggest that our in vitro model is capable of priming naïve CD8+ and CD4+ T cells to a broad, multispecific array of antigenic regions of HIV-1 Gag, Nef, and Env.

DISCUSSION

Primary antiviral CD8+ T-cell responses involve a series of events that are triggered by stimulation of the T-cell receptor on naïve CD8+ T cells, which, together with signaling by costimulatory and cytokine receptors, drive the magnitude and quality of the responder T cells (47). This process is central to the development of host adaptive immunity to HIV-1 and other viral infections. In the present study, we show that adult and neonatal myeloid moDC and neonatal LC and idDC were able to prime naïve CD8+ T cells to HIV-1 peptides and other viral peptides in vitro. The magnitude of the primary response was indicated by the significant number of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells specific for the peptides detected in the ELISPOT assay and was confirmed by tetramer staining. This magnitude of primary T-cell responses was noted after two repetitive stimulations with viral peptide-loaded DC in vitro.

Optimal priming of the adult CD8+ T cells by moDC to the viral antigens required prior maturation with CD40L and IFN-γ. Negligible levels of priming were induced by immature DC. We have recently shown that DC matured with CD40L and IFN-γ are highly efficient producers of IL-12 and have increased expression of T-cell coreceptors (16). These factors are involved in activation of recall CD8+ T-cell responses to specific antigens and are likely involved in direct priming of CD8+ T cells or through increases in Th1 cytokines that enhance primary CD8+ T-cell responses. Most importantly, efficient priming of CD8+ T cells in our study required the presence of autologous CD4+ T cells. This effect was not related to, or confounded by, antigen-specific activation of the CD4+ T cells, as was demonstrated with purified CD8+ T cells and with HLA A*0201-restricted 9-mer peptides matched with HLA A*0201 haplotype study subjects. A similar helper activity of CD4+ T cells has previously been shown for CD8+ T-cell priming to antigen-loaded adult LC (61). Although initial antigen stimulation via DC is considered sufficient to trigger CD8+ T-cell differentiation, CD4+ T cells are required to induce differentiation of the naïve CD8+ T cells into functional memory cells (3). Moreover, CD8+ T cells that are primed in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help are susceptible to activation-induced cell death (26). This suicidal process can be to some extent prevented by IL-15 (43), which we included in our adult T-cell priming studies. Interestingly, in our model, optimal priming of CD8+ T cells to HIV-1 p1777-85 SL9 (SLYNTVATL) was CD4+ T-cell dependent. This is in contrast to previous reports that priming in vitro to SL9 was uniquely CD4+ T-cell independent (28, 29). These dichotomous results could be related to conditions in the two priming systems, as the Kan-Mitchell priming model (28, 29) used a different type of maturation of the DC, different cytokines added to the priming cultures, and polyclonal expansion of the primed T cells.

The predominant phenotypes of the antigen-specific, primed neonatal CD8+ T cells were two antigen-experienced memory subsets, i.e., CD45+ CCR7− CD27+ and CD45− CCR7− CD27+. Similar proportions of each of these memory T-cell subpopulations were induced by moDC and LC, whereas idDC primed greater levels of CD45+ CCR7− CD27+ cells and lower levels of CD45− CCR7− CD27+ cells. A third population accounting for a smaller but distinct percentage of the peptide-specific cells was the naïve CD45+ CCR7+ CD27+ subset. Loss of CD45RA expression is considered a property of primed memory CD8 T cells (20). Virus-specific memory T-cell subsets with different functional properties have been further defined by expression of chemokine receptor CCR7 and costimulatory receptor CD27 (56). Using a similar priming method with neonatal moDC and CMV antigen, others have found that there is a predominance of CD45R− CD27+ T cells in the CMV-positive cell population (45). Similar to our results, Comoli et al. (9) found a predominant population of CD45RA− CD27−, and a secondary population of CD45RA+ CD27−, CD8+ T cells specific for EBV peptide in primed cultures from children. Likewise, Salio and colleagues (52) have reported that cord blood CD8+ T cells primed to melanoma peptide are predominately CD45− CCR7− CD27+. However, different modes of in vitro priming of T cells can result in various degrees of memory T-cell differentiation (9). Clearly, one should be cautious about interpreting T-cell phenotyping data from such in vitro priming systems due to the varied expression of these cell surface markers in natural viral infections (1, 22). Nevertheless, our results show that all three types of neonatal DC, i.e., moDC, LC, and idDC, prime similar antigen-specific, CD8+ T cells that are predominately a mixture of antigen-experienced CD45+ CCR7− CD27+ and CD45− CCR7− CD27+ phenotypes.

Polyfunctional T cells, defined by the simultaneous production of more than one immune mediator, have been shown to be important in control of HIV-1 and several other viral infections (2, 17, 36, 38, 46). Of importance is that although there is evidence of low T-cell immune responses in neonatal blood (39), neonatal CD8+ T cells primed to viral antigens in our study were both highly monofunctional and polyfunctional. Indeed, a relatively large percentage of CD8+ T cells primed to two HIV-1 9-mer peptides, one EBV 9-mer peptide, and one FLU 9-mer peptide, as well as to an HIV-1 20-mer (GQ20) containing the SL9 epitope, by the moDC, LC, and idDC, produced all five of the proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α, chemokine MIP1β, and the degranulation marker CD107a. Likewise, a large percentage of primed CD8+ T cells produced combinations of from two to five of these immune mediators. This suggests that these three different types of DC have a common capacity to mount a multifaceted, first-line T-cell attack on viral infections. Although this needs to be extended to adult donor DC-T-cell systems, it supports the importance of the use of this immune parameter in assessing prophylactic and immunotherapeutic vaccines. Of further interest is that there were significant differences in the priming of CD8+ T cells to some of the antigen-loaded DC subsets. In particular, our idDC primed more of the polyfunctional T cells than did the moDC or LC. This was in contrast to the lower priming of IFN-γ-producing T cells by idDC as detected by the ELISPOT assay. A recent report indicates that both LC and CD1a− CD14+ idDC efficiently prime CD8+ T cells to melanoma antigen (6). Furthermore, there is a subpopulation of CD1a+ CD14− CD207− dermal DC that activate antigen-specific CD8+ T cells less efficiently than LC (32). Finally, in mice, a population of CD207+ but not CD207− dermal DC such as those used in our study are involved in early priming of CD8+ T cells to Leishmania major (4). It is not clear if there is a comparable population of CD207 (Langerin)-positive cells in humans. Addressing these issues requires further, more in-depth examination of T-cell priming using highly purified DC subsets.

Our results indicate that moDC can prime CD8+ T cells to a broad range of epitopes in Gag, Env, and Nef. Using a stringent cutoff for a positive response and based on sequence comparison to known and predicted MHC class I epitopes, CD8+ T cells mounted strong primary responses to multiple Gag, Env, and Nef peptides. Indeed, analysis of the Los Alamos HIV Immunology Database identified many known and potential MHC class I epitopes for Gag, Env, and Nef among the peptide regions that were positive for T-cell reactivity in our priming system. Comparison of two unrelated, HIV-1-uninfected study subjects matched at two MHC class I alleles revealed some common reactivity to epitopes of their shared MHC class I alleles. A more extensive examination of primary T-cell reactivity using different N- and C-terminal lengths of these putative epitope regions will be necessary to map the fine specificity of primary T-cell responses to HIV-1.

Interestingly, we did not detect primary T-cell reactivity to known MHC class II epitopes. This could relate to the lower numbers of known MHC class II epitopes for HIV-1. Indeed, it is more difficult to detect anti-HIV-1-specific CD4+ T-cell epitopes than MHC class I-specific CD8+ T-cell epitopes in persons with HIV-1 infection (40). Moreover, our use of 15-mer peptides could be less ideal than use of longer peptides for processing and presentation of MHC class II epitopes, although studies have indicated that 15-mers are suitable for detection of CD4+ T-cell reactivity to MHC class II epitopes (14, 15, 31). We also primed the T cells with peptide-loaded DC that had been matured with CD40L and IFN-γ, which polarizes CD4+ Th1 cells to enhance CD8+ T-cell responses (37). We did, however, detect T-cell reactivity to a large number of potential MHC class II epitopes based on C-terminal as well as N-terminal anchor residues matching one or more motifs associated with the respective HLA DR and DQ alleles. Confirmation that these predicted epitopes are functional, CD4+ T-cell epitopes requires that they be mapped to their minimal size for MHC class II alleles. Finally, the other regions of these HIV-1 proteins that induced T-cell reactivity not in association with known or predicted T-cell epitopes could represent additional MHC class I and MHC class II specificities that remain to be defined.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the potent capability of moDC derived from normal adult donor blood to induce a broad spectrum of primary CD8+ T-cell responses to HIV-1 and other viral epitopes. The primed CD8+ T cells exhibited HIV-1 peptide-specific cytolytic activity and IFN-γ production that was optimized by the presence of autologous CD4+ T cells. Moreover, we show that three major types of DC derived from neonatal cord blood, i.e., moDC, LC, and idDC, also can prime monofunctional and polyfunctional CD8+ T cells specific for HIV-1 and other viral peptides. Because the control of HIV-1 replication is largely dependent on CD8+ T lymphocyte responses specific for immunodominant viral epitopes, vaccines that increase the breadth of epitope-specific responses should contribute to containing HIV-1 spread. Developing strategies to elicit such a broad spectrum of T-cell responses will require an understanding of the mechanisms responsible for such immunodominance (42). We propose that engineering DC to enhance the primary responses of naïve CD8+ T cells to a broad array of HIV-1 epitopes while patients are on antiretroviral therapy could ultimately improve control of viral replication and disease (49). This in vitro priming model makes it possible to evaluate potential epitopes and their immunogenicities for vaccine application.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amgen (Seattle, WA) for providing CD40L (MTA no. 200312724); W. Jiang, P. Zhang, E. Molina, M. Jais, and K. Stojka for technical assistance; A. Hoji and P. Piazza for technical advice; Mario Roederer (VRC/NIAID/NIH) for SPICE (version 4.1.6); and W. Buchanan for clinical assistance.

This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants R01 CA82053, U01 AI-35041, and R37 AI-41870.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 April 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appay, V., R. A. van Lier, F. Sallusto, and M. Roederer. 2008. Phenotype and function of human T lymphocyte subsets: consensus and issues. Cytometry A 73975-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betts, M. R., M. C. Nason, S. M. West, S. C. De Rosa, S. A. Migueles, J. Abraham, M. M. Lederman, J. M. Benito, P. A. Goepfert, M. Connors, M. Roederer, and R. A. Koup. 2006. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood 1074781-4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bevan, M. J. 2004. Helping the CD8(+) T-cell response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4595-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewig, N., A. Kissenpfennig, B. Malissen, A. Veit, T. Bickert, B. Fleischer, S. Mostbock, and U. Ritter. 2009. Priming of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in experimental leishmaniasis is initiated by different dendritic cell subtypes. J. Immunol. 182774-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brossart, P., F. Grunebach, G. Stuhler, V. L. Reichardt, R. Mohle, L. Kanz, and W. Brugger. 1998. Generation of functional human dendritic cells from adherent peripheral blood monocytes by CD40 ligation in the absence of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood 924238-4247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao, T., H. Ueno, C. Glaser, J. W. Fay, A. K. Palucka, and J. Banchereau. 2007. Both Langerhans cells and interstitial DC cross-present melanoma antigens and efficiently activate antigen-specific CTL. Eur. J. Immunol. 372657-2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castelli, F. A., D. Houitte, G. Munier, N. Szely, A. Lecoq, J. P. Briand, S. Muller, and B. Maillere. 2008. Immunoprevalence of the CD4+ T-cell response to HIV Tat and Vpr proteins is provided by clustered and disperse epitopes, respectively. Eur. J. Immunol. 382821-2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caux, C., C. Massacrier, B. Vanbervliet, B. Dubois, B. de Saint-Vis, C. Dezutter-Dambuyant, C. Jacquet, D. Schmitt, and J. Banchereau. 1997. CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors from human cord blood differentiate along two independent dendritic cell pathways in response to GM-CSF+TNF alpha. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 41721-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comoli, P., F. Ginevri, R. Maccario, C. Frasson, U. Valente, S. Basso, M. Labirio, G. C. Huang, E. Verrina, F. Baldanti, F. Perfumo, and F. Locatelli. 2006. Successful in vitro priming of EBV-specific CD8+ T cells endowed with strong cytotoxic function from T cells of EBV-seronegative children. Am. J. Transplant. 62169-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Currier, J. R., E. G. Kuta, E. Turk, L. B. Earhart, L. Loomis-Price, S. Janetzki, G. Ferrari, D. L. Birx, and J. H. Cox. 2002. A panel of MHC class I restricted viral peptides for use as a quality control for vaccine trial ELISPOT assays. J. Immunol. Methods 260157-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deeks, S. G., and B. D. Walker. 2007. Human immunodeficiency virus controllers: mechanisms of durable virus control in the absence of antiretroviral therapy. Immunity 27406-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Witte, L., A. Nabatov, and T. B. Geijtenbeek. 2008. Distinct roles for DC-SIGN+-dendritic cells and Langerhans cells in HIV-1 transmission. Trends Mol. Med. 1412-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Witte, L., A. Nabatov, M. Pion, D. Fluitsma, M. A. de Jong, T. de Gruijl, V. Piguet, Y. van Kooyk, and T. B. Geijtenbeek. 2007. Langerin is a natural barrier to HIV-1 transmission by Langerhans cells. Nat. Med. 13367-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Draenert, R., M. Altfeld, C. Brander, N. Basgoz, C. Corcoran, A. G. Wurcel, D. R. Stone, S. A. Kalams, A. Trocha, M. M. Addo, P. J. Goulder, and B. D. Walker. 2003. Comparison of overlapping peptide sets for detection of antiviral CD8 and CD4 T cell responses. J. Immunol. Methods 27519-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubey, S., J. Clair, T. M. Fu, L. Guan, R. Long, R. Mogg, K. Anderson, K. B. Collins, C. Gaunt, V. R. Fernandez, L. Zhu, L. Kierstead, S. Thaler, S. B. Gupta, W. Straus, D. Mehrotra, T. W. Tobery, D. R. Casimiro, and J. W. Shiver. 2007. Detection of HIV vaccine-induced cell-mediated immunity in HIV-seronegative clinical trial participants using an optimized and validated enzyme-linked immunospot assay. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 4520-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan, Z., X. L. Huang, P. Kalinski, S. Young, and C. R. Rinaldo, Jr. 2007. Dendritic cell function during chronic hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 141127-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuhrmann, S., M. Streitz, P. Reinke, H. D. Volk, and F. Kern. 2008. T cell response to the cytomegalovirus major capsid protein (UL86) is dominated by helper cells with a large polyfunctional component and diverse epitope recognition. J. Infect. Dis. 1971455-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillespie, G. M., M. R. Wills, V. Appay, C. O'Callaghan, M. Murphy, N. Smith, P. Sissons, S. Rowland-Jones, J. I. Bell, and P. A. Moss. 2000. Functional heterogeneity and high frequencies of cytomegalovirus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in healthy seropositive donors. J. Virol. 748140-8150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruber, A., J. Kan-Mitchell, K. L. Kuhen, T. Mukai, and F. Wong-Staal. 2000. Dendritic cells transduced by multiply deleted HIV-1 vectors exhibit normal phenotypes and functions and elicit an HIV-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in vitro. Blood 961327-1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamann, D., P. A. Baars, M. H. Rep, B. Hooibrink, S. R. Kerkhof-Garde, M. R. Klein, and R. A. van Lier. 1997. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector human CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1861407-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hart, J. P., M. D. Gunn, and S. V. Pizzo. 2004. A CD91-positive subset of CD11c+ blood dendritic cells: characterization of the APC that functions to enhance adaptive immune responses against CD91-targeted antigens. J. Immunol. 17270-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoji, A., N. C. Connolly, W. G. Buchanan, and C. R. Rinaldo, Jr. 2007. CD27 and CD57 expression reveals atypical differentiation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific memory CD8+ T cells. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 1474-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang, X. L., Z. Fan, L. Borowski, and C. R. Rinaldo. 2008. Maturation of dendritic cells for enhanced activation of anti-HIV-1 CD8(+) T cell immunity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 831530-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang, X. L., Z. Fan, B. A. Colleton, R. Buchli, H. Li, W. H. Hildebrand, and C. R. Rinaldo, Jr. 2005. Processing and presentation of exogenous HLA class I peptides by dendritic cells from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected persons. J. Virol. 793052-3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang, X. L., Z. Fan, L. Zheng, L. Borowski, H. Li, E. K. Thomas, W. H. Hildebrand, X. Q. Zhao, and C. R. Rinaldo, Jr. 2003. Priming of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific CD8+ T cell responses by dendritic cells loaded with HIV-1 proteins. J. Infect. Dis. 187315-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janssen, E. M., E. E. Lemmens, T. Wolfe, U. Christen, M. G. von Herrath, and S. P. Schoenberger. 2003. CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature 421852-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jonuleit, H., U. Kuhn, G. Muller, K. Steinbrink, L. Paragnik, E. Schmitt, J. Knop, and A. H. Enk. 1997. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandins induce maturation of potent immunostimulatory dendritic cells under fetal calf serum-free conditions. Eur. J. Immunol. 273135-3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kan-Mitchell, J., M. Bajcz, K. L. Schaubert, D. A. Price, J. M. Brenchley, T. E. Asher, D. C. Douek, H. L. Ng, O. O. Yang, C. R. Rinaldo, Jr., J. M. Benito, B. Bisikirska, R. Hegde, F. M. Marincola, C. Boggiano, D. Wilson, J. Abrams, S. E. Blondelle, and D. B. Wilson. 2006. Degeneracy and repertoire of the human HIV-1 Gag p17(77-85) CTL response. J. Immunol. 1766690-6701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kan-Mitchell, J., B. Bisikirska, F. Wong-Staal, K. L. Schaubert, M. Bajcz, and M. Bereta. 2004. The HIV-1 HLA-A2-SLYNTVATL is a help-independent CTL epitope. J. Immunol. 1725249-5261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawamura, T., Y. Koyanagi, Y. Nakamura, Y. Ogawa, A. Yamashita, T. Iwamoto, M. Ito, A. Blauvelt, and S. Shimada. 2008. Significant virus replication in Langerhans cells following application of HIV to abraded skin: relevance to occupational transmission of HIV. J. Immunol. 1803297-3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiecker, F., M. Streitz, B. Ay, G. Cherepnev, H. D. Volk, R. Volkmer-Engert, and F. Kern. 2004. Analysis of antigen-specific T-cell responses with synthetic peptides—what kind of peptide for which purpose? Hum. Immunol. 65523-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klechevsky, E., R. Morita, M. Liu, Y. Cao, S. Coquery, L. Thompson-Snipes, F. Briere, D. Chaussabel, G. Zurawski, A. K. Palucka, Y. Reiter, J. Banchereau, and H. Ueno. 2008. Functional specializations of human epidermal langerhans cells and CD14+ dermal dendritic cells. Immunity 29497-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lapenta, C., S. M. Santini, M. Spada, S. Donati, F. Urbani, D. Accapezzato, D. Franceschini, M. Andreotti, V. Barnaba, and F. Belardelli. 2006. IFN-alpha-conditioned dendritic cells are highly efficient in inducing cross-priming CD8(+) T cells against exogenous viral antigens. Eur. J. Immunol. 362046-2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, W., D. K. Krishnadas, R. Kumar, D. L. Tyrrell, and B. Agrawal. 2008. Priming and stimulation of hepatitis C virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells against HCV antigens NS4, NS5a or NS5b from HCV-naive individuals: implications for prophylactic vaccine. Int. Immunol. 2089-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li, W., D. K. Krishnadas, J. Li, D. L. Tyrrell, and B. Agrawal. 2006. Induction of primary human T cell responses against hepatitis C virus-derived antigens NS3 or core by autologous dendritic cells expressing hepatitis C virus antigens: potential for vaccine and immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 1766065-6075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lore, K., W. C. Adams, M. J. Havenga, M. L. Precopio, L. Holterman, J. Goudsmit, and R. A. Koup. 2007. Myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells are susceptible to recombinant adenovirus vectors and stimulate polyfunctional memory T cell responses. J. Immunol. 1791721-1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mailliard, R. B., A. Wankowicz-Kalinska, Q. Cai, A. Wesa, C. M. Hilkens, M. L. Kapsenberg, J. M. Kirkwood, W. J. Storkus, and P. Kalinski. 2004. Alpha-type-1 polarized dendritic cells: a novel immunization tool with optimized CTL-inducing activity. Cancer Res. 645934-5937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makedonas, G., and M. R. Betts. 2006. Polyfunctional analysis of human T cell responses: importance in vaccine immunogenicity and natural infection. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 28209-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marchant, A., and M. Goldman. 2005. T cell-mediated immune responses in human newborns: ready to learn? Clin. Exp. Immunol. 14110-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meddows-Taylor, S., S. Shalekoff, L. Kuhn, G. E. Gray, and C. T. Tiemessen. 2007. Development of a whole blood intracellular cytokine staining assay for mapping CD4(+) and CD8(+) T-cell responses across the HIV-1 genome. J. Virol. Methods 144115-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehta-Damani, A., S. Markowicz, and E. G. Engleman. 1995. Generation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cell lines from naive precursors. Eur. J. Immunol. 251206-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newberg, M. H., K. J. McEvers, D. A. Gorgone, M. A. Lifton, S. H. Baumeister, R. S. Veazey, J. E. Schmitz, and N. L. Letvin. 2006. Immunodomination in the evolution of dominant epitope-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte responses in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys. J. Immunol. 176319-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oh, S., L. P. Perera, M. Terabe, L. Ni, T. A. Waldmann, and J. A. Berzofsky. 2008. IL-15 as a mediator of CD4+ help for CD8+ T cell longevity and avoidance of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1055201-5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papagno, L., C. A. Spina, A. Marchant, M. Salio, N. Rufer, S. Little, T. Dong, G. Chesney, A. Waters, P. Easterbrook, P. R. Dunbar, D. Shepherd, V. Cerundolo, V. Emery, P. Griffiths, C. Conlon, A. J. McMichael, D. D. Richman, S. L. Rowland-Jones, and V. Appay. 2004. Immune activation and CD8+ T-cell differentiation towards senescence in HIV-1 infection. PLoS Biol. 2E20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park, K. D., L. Marti, J. Kurtzberg, and P. Szabolcs. 2006. In vitro priming and expansion of cytomegalovirus-specific Th1 and Tc1 T cells from naive cord blood lymphocytes. Blood 1081770-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Precopio, M. L., M. R. Betts, J. Parrino, D. A. Price, E. Gostick, D. R. Ambrozak, T. E. Asher, D. C. Douek, A. Harari, G. Pantaleo, R. Bailer, B. S. Graham, M. Roederer, and R. A. Koup. 2007. Immunization with vaccinia virus induces polyfunctional and phenotypically distinctive CD8(+) T cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 2041405-1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prlic, M., M. A. Williams, and M. J. Bevan. 2007. Requirements for CD8 T-cell priming, memory generation and maintenance. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 19315-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ratzinger, G., J. Baggers, M. A. de Cos, J. Yuan, T. Dao, J. L. Reagan, C. Munz, G. Heller, and J. W. Young. 2004. Mature human Langerhans cells derived from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors stimulate greater cytolytic T lymphocyte activity in the absence of bioactive IL-12p70, by either single peptide presentation or cross-priming, than do dermal-interstitial or monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 1732780-2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rinaldo, C. R. 2009. Dendritic cell-based human immunodeficiency virus vaccine. J. Intern. Med. 265138-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rinaldo, C. R., Jr., and P. Piazza. 2004. Virus infection of dendritic cells: portal for host invasion and host defense. Trends Microbiol. 12337-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romani, N., S. Gruner, D. Brang, E. Kampgen, A. Lenz, B. Trockenbacher, G. Konwalinka, P. O. Fritsch, R. M. Steinman, and G. Schuler. 1994. Proliferating dendritic cell progenitors in human blood. J. Exp. Med. 18083-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salio, M., N. Dulphy, J. Renneson, M. Herbert, A. McMichael, A. Marchant, and V. Cerundolo. 2003. Efficient priming of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by human cord blood dendritic cells. Int. Immunol. 151265-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salio, M., D. Shepherd, P. R. Dunbar, M. Palmowski, K. Murphy, L. Wu, and V. Cerundolo. 2001. Mature dendritic cells prime functionally superior melan-A-specific CD8+ lymphocytes as compared with nonprofessional APC. J. Immunol. 1671188-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schaubert, K. L., D. A. Price, N. Frahm, J. Li, H. L. Ng, A. Joseph, E. Paul, B. Majumder, V. Ayyavoo, E. Gostick, S. Adams, F. M. Marincola, A. K. Sewell, M. Altfeld, J. M. Brenchley, D. C. Douek, O. O. Yang, C. Brander, H. Goldstein, and J. Kan-Mitchell. 2007. Availability of a diversely avid CD8+ T cell repertoire specific for the subdominant HLA-A2-restricted HIV-1 Gag p2419-27 epitope. J. Immunol. 1787756-7766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schlienger, K., N. Craighead, K. P. Lee, B. L. Levine, and C. H. June. 2000. Efficient priming of protein antigen-specific human CD4(+) T cells by monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood 963490-3498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomiyama, H., H. Takata, T. Matsuda, and M. Takiguchi. 2004. Phenotypic classification of human CD8+ T cells reflecting their function: inverse correlation between quantitative expression of CD27 and cytotoxic effector function. Eur. J. Immunol. 34999-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trinchieri, G. 2003. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3133-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tschachler, E., V. Groh, M. Popovic, D. L. Mann, K. Konrad, B. Safai, L. Eron, F. DiMarzo Veronese, K. Wolff, and G. Stingl. 1987. Epidermal Langerhans cells—a target for HTLV-III/LAV infection. J. Investig. Dermatol. 88233-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turville, S. G., P. U. Cameron, A. Handley, G. Lin, S. Pohlmann, R. W. Doms, and A. L. Cunningham. 2002. Diversity of receptors binding HIV on dendritic cell subsets. Nat. Immunol. 3975-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilson, C. C., W. C. Olson, T. Tuting, C. R. Rinaldo, M. T. Lotze, and W. J. Storkus. 1999. HIV-1-specific CTL responses primed in vitro by blood-derived dendritic cells and Th1-biasing cytokines. J. Immunol. 1623070-3078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuan, J., J. B. Latouche, J. Hodges, A. N. Houghton, G. Heller, M. Sadelain, I. Riviere, and J. W. Young. 2006. Langerhans-type dendritic cells genetically modified to express full-length antigen optimally stimulate CTLs in a CD4-dependent manner. J. Immunol. 1762357-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zarling, A. L., J. G. Johnson, R. W. Hoffman, and D. R. Lee. 1999. Induction of primary human CD8+ T lymphocyte responses in vitro using dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 1625197-5204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]