Abstract

The androgen receptor (AR) is a ligand activated nuclear receptor, which regulates transcription and stimulates growth of androgen dependent prostate cancer. To regulate transcription, AR recruits a series of coactivators that modify chromatin and facilitate transcription. However, information on ligand and target gene specific requirements for coactivators is limited. We compared the actions of the p160 coactivators SRC-1 and SRC-3/RAC3 with SRA (steroid receptor RNA activator). All three coactivate AR in the presence of agonist as expected. However, overexpression of either SRC-1 or SRC-3 increased AR activity in response to the partial antagonist, cyproterone acetate, whereas SRA was unable to stimulate AR activity under these conditions. Using siRNA to reduce expression of these coactivators in LNCaP cells, we also found promoter specific requirement for these coactivators. SRC-3 is required for optimal androgen dependent induction of PSA, TMPRSS2, and PMEPA1 whereas SRA is required only for optimal induction of the TMPRSS2 gene. These data indicate that different groups of AR target genes have distinct requirements for coactivators and response to AR ligands.

Keywords: androgen receptor, SRA, RAC-3, SRC-3, cyproterone acetate, LNCaP

Introduction

Prostate cancer is an androgen dependent disease; consequently, androgen deprivation therapy is the primary treatment for metastatic disease. Androgens act through the androgen receptor (AR) and increased AR protein expression is associated with poor prognosis [1]. The relatively short time of response to androgen deprivation therapy prior to recurrence (typically <2 years) and the evidence that AR is reactivated in recurrent tumors [2] have led to efforts to better understand the factors that regulate AR action in order to develop more effective anti-AR therapies. In order to regulate transcription of target genes, AR must recruit a series of coactivator complexes that modify chromatin and facilitate transcription. A multitude of proteins have been suggested as putative AR coactivators; these candidates have been identified based on their physical interactions with AR and their capacity when overexpressed to enhance induction of an AR responsive reporter [3]. Moreover, using these approaches, there is some evidence that overexpression of specific coactivators such as ARA70 [4] can broaden the specificity of the ligands that activate AR to include estradiol and some compounds, which normally function as antagonists.

Information regarding the contribution of endogenous coactivators to the target gene-specific regulation of AR target genes in prostate cancer cells is limited. One of the best described groups of steroid receptor coactivators is the p160 family, which consists of SRC-1, TIF2/SRC-2 and RAC3/AIB1/SRC-3. We have previously shown that a p160 coactivator, SRC-1, is important for AR transcriptional activity in prostate cancer cells and that patients expressing high levels of SRC-1 have a higher risk for developing more aggressive tumors [5]. We have also shown that another p160 coactivator, TIF2, is necessary for optimal transcriptional activity of AR, and for both the AR dependent and AR independent proliferation of human prostate cancer cell lines [6]. TIF2 expression increases with prostate cancer progression and is maximal in recurrent cancers that have failed androgen ablation [6]. Interestingly, TIF2 expression is repressed by androgens and inhibition of AR signaling due to androgen deprivation increased TIF2 expression. RAC3 is overexpressed or amplified in prostate cancer and correlates with poor prognosis [7]. RAC3 also increases expression of BCL2 and Akt independently of AR [7,8]. However the contribution of RAC3 to androgen-dependent regulation of AR target genes has not been reported. Another coactivator whose contribution to androgen-dependent target gene expression has not been examined is SRA. SRA (steroid receptor RNA activator) is an RNA found in SRC-1 associated complexes, which potentiate steroid receptor activity [9]. There is evidence from a mouse transgenic model overexpressing SRA, that SRA plays a role in prostate growth. Overexpression of SRA was insufficient to induce prostate cancer [10], but it caused both increased proliferation and increased apoptosis in prostate epithelium [10]. In this study, we sought to determine whether overexpression of RAC3 or SRA would broaden the ligand specificity of AR and whether depletion of RAC3 or SRA in LNCaP prostate cancer cells would alter androgen-dependent transcription. We found that RAC3 had similar characteristics to the other p160 coactivators, but that SRA had a distinctly different pattern of actions.

Experimental

Cell Culture and supplies

LNCaP, PC-3, DU145, and HeLa cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). LNCaP cells were propagated in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Intergen Co., Purchase, NY) and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). HeLa cells were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen), 10% FBS, and penicillin/streptomycin. PC-3 cells were maintained in DMEM/F12, 10% FBS, and penicillin/streptomycin and DU145 cells in MEM + 1% L-glutamine, 10% FBS, and penicillin/streptomycin. All cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Methyltrienolone (R1881) was purchased from Perkin-Elmer (Boston, MA), cyproterone acetate (CPA) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and [3H]thymidine from ICN (Irvine, CA).

Transient transfections

Cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids using a poly-L-lysine coupled adenovirus procedure as described previously [11]. Cells were treated as described, lysed, and luciferase and β-Galactosidase activity measured as previously described [11]. GRE2e1b-luciferase reporter, pCR3.1 β-galactosidase, pCR3.1-AR, pCR3.1-SRC-1, pSCT-SRA were described previously [9,11] and pCR3.1-RAC3 was a gift from Dr. Carolyn Smith (Baylor College of Medicine).

Transfection of siRNAs

Two million LNCaP cells were electroporated with 800 pmoles of siRNA in buffer R (sold by Amaxa for transfection of LNCaP cells) using a nucleofector (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD). Cells were then split into 2×6-well plates coated with polylysine. RAC3 siRNAs used in this study were RAC3 SMARTpool (a pre-mixed pool of 4 independent siRNAs from Dharmacon Research, Inc., Lafayette, CO), and 3 individual RAC3 siRNAs ordered from Dharmacon Research, Inc. RAC3-1 AACACAATACCTGCAATATAA, RAC3-2 AAGAAAGGTTGTCAATATAGA, RAC3-3 AAGAAGGTGTATTCTGAGATT. SRA was downregulated using SMARTpool siRNA called SRA in the text (Dharmacon) or a custom made siRNA (named SRA2) to the following sequence AATACCTGTAAAGAAGAGAAT.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in TESH buffer [10 mmol/L Tris, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 12 mmol/L thioglycerol (pH 7.7)] containing 0.4 M NaCl by three rounds of freeze/thaw; 30 μg of protein were resolved on a 6.5% SDS gel. Proteins were detected as described using either a RAC3 antibody (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) at a 1:200 dilution, an actin antibody (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) at a 1:1000 dilution, or a previously described AR antibody, AR441 [12], at a 1:1000 dilution and ECL reagents.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was prepared using TRIzol reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Target gene expression was analyzed using TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master mix reagent and an ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system. For SRA the primers and probe were: TCTACTGGTGCAAGAGCTTTCAAG, ATGAGGGAGCGGTGGATGT, FAM-CACCGGTGGGACGCAGCAGAT-TAMRA. RAC3 was detected using the following primers and probe: TTGTTGGGCCACCTTCCA, AGAGTGTGCAGCTGGTCCAAT, FAM-TGGAAGGCCAGAGTGACGAAAGAGCA-TAMRA. Predesigned 18S primers and probe mix were purchased from Applied Biosystems. PSA, TMPRSS2, and PMEPA1 primer and probe sets were described previously [6].

Proliferation assay

Incorporation of [3H]thymidine was used to compare the rates of cell proliferation. Cells were incubated in the indicated medium for 3 hours with 2 μCi/ml of [3H]thymidine. Cells were then fixed and incorporated [3H]thymidine counted as previously described [5].

All experiments were performed a minimum of three times and a representative experiment is shown. Within each experiment three independent wells were used for isolation of RNA or for measurements of [3H]thymidine incorporation and the bars represent the mean +/− standard error.

Results

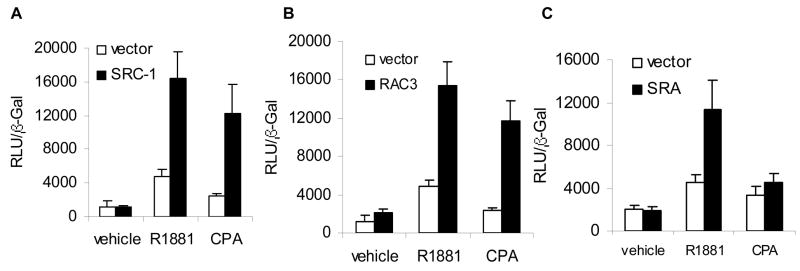

Elevated expression of SRC-1 or RAC3, but not SRA, induces cyproterone acetate (CPA)-dependent AR activity

Agonist dependent potentiation of AR activity by SRC-1, RAC3, and SRA measured using transiently transfected AR and reporters has been reported previously [4,9,13]. To determine whether overexpression of these coactivators can broaden the range of ligands used as agonists by AR, we asked whether overexpression of the coactivators caused CPA, a partial AR antagonist that has been used to treat prostate cancer [14], to induce AR dependent activity. As expected, increased expression of SRC-1, RAC3, or SRA increased agonist (R1881) dependent activity in HeLa cells transfected with an AR responsive luciferase reporter and an AR expression plasmid (Figure 1). Basal levels of transcription in the absence of hormone were unaffected. While both p160 coactivators, SRC-1 and RAC3, induced CPA-dependent AR activity (Fig. 1A and 1B), SRA did not (Fig. 1C) suggesting distinct roles for these coactivators.

Figure 1. SRC-1 and RAC3 induce CPA-dependent AR activity.

To determine whether overexpression of coactivators broadens ligand specificity, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 400 ng of GRE2e1b-luciferase reporter, 30 ng of pCR3.1 β-galactosidase, 5 ng of pCR3.1-AR, and the indicated amounts of vector or plasmid, treated with vehicle (ethanol), 1 nM R1881, or 30 nM CPA for 24 hours, and luciferase and β-galactosidase activity measured. A. 400 ng of either pCR3.1 or pCR3.1-SRC-1B were used. B. 400 ng pCR3.1 or pCR3.1-RAC3 were used. C. 400 ng of pSCT or pSCT-SRA were used.

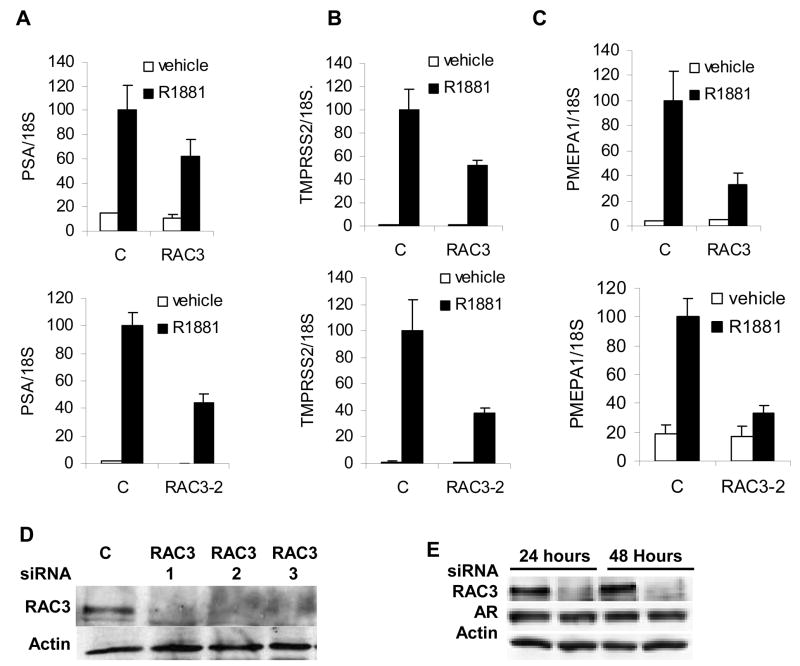

RAC3 is required for optimal induction of AR target genes

To determine if endogenous RAC3 expression is required for AR signaling we examined the effect of decreasing RAC3 expression on the expression of AR target genes in LNCaP prostate cancer cells (Figures 2A, 2B, and 2C). To reduce RAC3 protein levels we used RAC3 siRNA SMARTpool and 3 separate siRNAs (Dharmacon). Three distinct siRNAs specific to RAC3, RAC3-1, RAC3-2, and RAC3-3, all efficiently reduce RAC3 protein levels at 48 hours after transfection (Figure 2D). RAC3 siRNA SMARTpool reduced RAC3 protein levels at both 24 and 48 hours (Figure 2E). We depleted RAC3 levels using Dharmacon SMARTpool and found that expression of AR target genes PSA, TMPRSS2, and PMEPA1 (Figures 2A, 2B, and 2C upper panels) was reduced. Similar results were obtained with siRNAs for RAC-1, RAC3-2, and RAC3-3 (data shown for RAC3-2 in Figures 2A, 2B, and 2C lower panels). Interestingly, the expression levels of PMEPA1 are more sensitive to RAC3 depletion than are PSA and TMPRSS2. The average PMEPA1 expression from 5 independent experiments in R1881 treated cells depleted of RAC3 was 35.8 ± 3.3% of R1881 treated cells transfected with the control siRNA, whereas for TMPRSS2 and PSA the averages were 53.7 ± 4.7 and 62.3 ± 8.6 respectively.

Figure 2. RAC3 is required for optimal androgen-dependent induction of target genes.

To determine whether RAC3 is required for androgen receptor dependent gene regulation, LNCaP cells were treated with control (C), RAC3 specific siRNA (RAC3) (Dharmacon SMARTpool), or RAC3-2 siRNA, cells grown in medium supplemented with stripped serum for 24 hours and treated with vehicle or 1 nM R1881 for another 24 hours and gene expression measured. A, PSA; B, TMPRSS2; C, PMEPA1. All values were normalized for 18S expression, and average and standard deviation calculated. D. To confirm that the siRNAs reduced RAC3 expression, LNCaP cells were transfected with either control or three distinct RAC3-specific siRNAs, RAC3-1, RAC3-2, RAC3-3, cells were harvested 48 hours after the transfection and analyzed for RAC3 expression by Western blotting. E. Cells were transfected as above with either noncoding control or RAC3 siRNA SMARTpool (Dharmacon). Cells were harvested 24 or 48 hours after transfection and analyzed for RAC3 expression by Western blotting. Average and standard deviation were calculated and each experiment repeated at least three times.

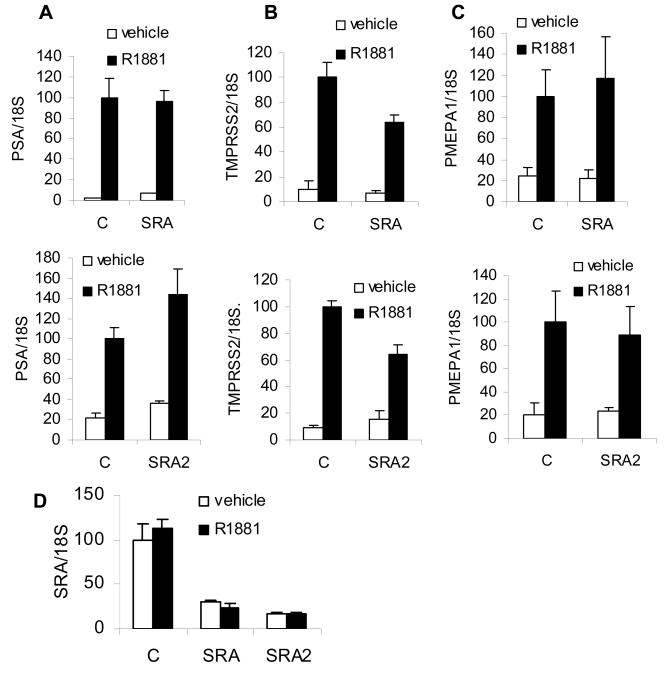

Coactivation by SRA is target gene dependent

To determine whether endogenous SRA is required for AR transcriptional activity, we downregulated SRA using two different siRNAs and measured the extent of AR target gene induction (Figures 3A, 3B, 3C). To downregulate SRA we used a custom designed siRNA as well as SRA SMARTpool siRNAs. Both SRA SMARTpool and SRA2 siRNAs substantially reduced SRA expression in LNCaP after 24 hour treatment (Figures 3D). Interestingly, only TMPRSS2 expression was reduced in cells depleted of SRA by SMARTpool siRNA (Figure 3B upper panel), while PSA and PMEPA1 expression were not affected (Figures 3A and 3C, upper panels). Similar effects on target gene expression were observed using a custom made siRNA SRA2 (Figures 3A, 3B, and 3C, lower panels).

Figure 3. SRA is not required for transcription of all AR induced genes.

A–C. To determine whether SRA is required for androgen dependent gene regulation, LNCaP cells were electroporated with control, SMARTpool siRNA (SRA), or custom designed SRA2 siRNA, grown in medium with stripped serum for 24 hours, treated for an additional 24 hours with vehicle or 1 nM R1881 and mRNA levels measured. A, PSA; B, TMPRSS2; C, PMEPA1; D, SRA.

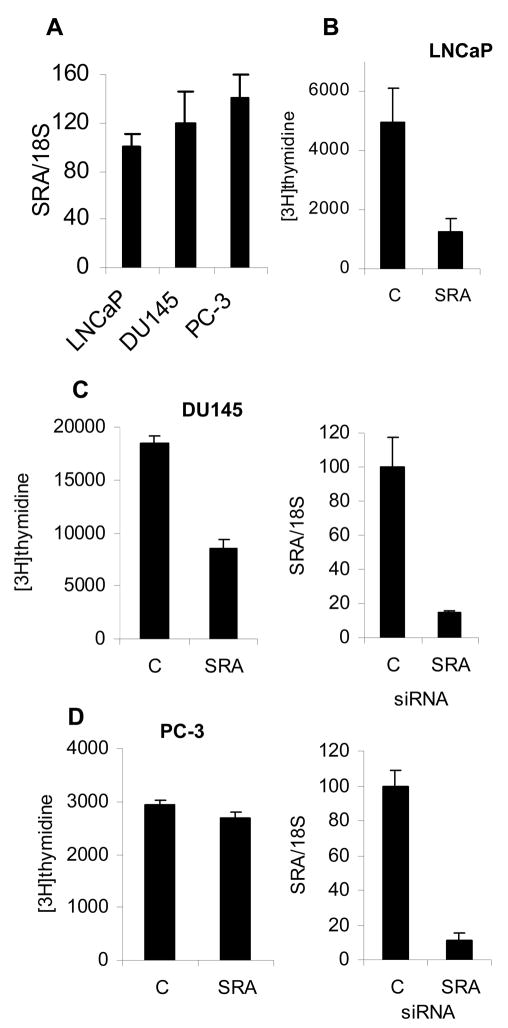

SRA is required for optimal growth of LNCaP and DU145 prostate cancer cells

Because depletion of any one of the p160 coactivators reduces cellular proliferation of LNCaP cells [5–7,11], but only TIF2 [6] and RAC3 [7] were necessary for proliferation of cells that do not express AR, we asked whether SRA is required for growth of AR dependent and independent cell lines. SRA expression is similar in AR positive LNCaP, AR negative DU145, and AR negative PC-3 prostate cancer cell lines (Figure 4A). Downregulation of SRA in the LNCaP cell line decreased proliferation (Figure 4B). Surprisingly, depletion of SRA in DU145 cells also reduced proliferation while in PC-3 cells it did not (Figure 4C and 4D left panels) despite similar levels of SRA downregulation (Figure 4C and 4D right panels).

Figure 4. SRA is required for optimal growth of LNCaP and DU145 cells.

A. Expression levels of SRA in LNCaP, DU145, and PC-3 cells were compared by normalizing SRA expression with 18S expression and levels reported as percent of SRA expression in LNCaP cells. B. To determine whether SRA is required for optimal cell growth, LNCaP cells were transfected with control or SMARTpool SRA siRNA split into 2 6-well plates, grown in charcoal stripped serum for 24 hours, treated with 1 nM R1881 for another 24 hours and proliferation measured using [3H] thymidine as described in methods. C. DU145 cells were transfected with 50 pmoles of either control or SRA siRNA per well using lipofectamine transfection as previously described [5] and [3H] thymidine incorporation measured 48 hours after transfection. Cells transfected in parallel were used for RNA extraction and real time RTPCR analysis of SRA expression. F. PC-3 cells were transfected with noncoding control (C) or SRA SMARTpool siRNA exactly the same as the DU145 cells and [3H]thymidine incorporation measured. Relative SRA expression levels were determined by quantitative RTPCR. SRA expression was assigned as 100 in cells transfected with C siRNA.

Discussion

These studies demonstrate that although coactivators appear interchangeable in increasing AR activity measured using a reporter, their activities are distinct. We show, here, that in addition to the broadening of ligand specificity reported previously for ARA70 [4,15], overexpression of the p160 coactivators SRC-1 and RAC3 also broaden specificity causing CPA to activate AR. In contrast, although SRA potentiates agonist dependent AR activity, overexpression of SRA is insufficient to cause CPA to function as an agonist.

Similar to SRC-1 and TIF2, RAC3 is required for optimal induction of AR target genes. However, PMEPA1 induction is more dependent upon RAC3 than are the other genes. Whether the stronger requirement for RAC3 is due to its function as an AR coactivator or to its independent actions in regulating other functions such as the levels of Akt remains to be determined. However, basal levels of PMEPA1 are unaffected by depletion of RAC3 suggesting that the contribution is AR dependent.

The original studies of SRA function demonstrated that SRA functions as an RNA to stimulate steroid receptor mediated transcription. This RNA interacts with a variety of proteins and may serve as a scaffold to recruit these proteins to receptors [16–18]. There are many splice variants of SRA. More recently, variants that encode proteins, termed SRAP [19], have been identified. These proteins also stimulate the activity of steroid receptors. The expression vector utilized in Figure 1 encodes the RNA form and thus tests the capacity of the RNA to broaden ligand specificity. However, the siRNAs utilized in the subsequent studies are directed towards the core sequence and eliminate the RNA forms as well as the coding sequence for any potential SRAPs. Thus, our finding that SRA does not contribute to either PSA or PMEPA1 expression indicates that neither the RNA coactivator nor SRAP contribute to the regulation of this gene. The finding that the serine protease, TMPRSS2, is regulated by SRA is of particular interest in prostate cancer. The role, if any, for the TMPRSS2 in prostate cancer has not been identified. However, recent findings show that a very high percentage of human prostate tumors (>60%) contain a somatic translocation or deletion that fuses the androgen regulated promoter of the TMPRSS2 gene to a portion of the coding region of oncogenic ETS factors [20,21]. Thus, SRA expression should regulate the expression of this important fusion.

PSA expression typically is used as a surrogate for AR activity in LNCaP cells. These target gene selective requirements for coactivators are the second example we have found for selective requirements for AR induced genes. In studies to examine the effects of p42/p44 MAPK activity on AR function, we found that the MEK inhibitor, U0126, reduced androgen dependent expression of PSA and TMPRSS2, but not PMEPA1 [22]. Whereas androgen induces U0126 sensitive histone acetylation at the PSA and TMPRSS2 AR binding sites, AR activates PMEPA1 without causing comparable increases in histone acetylation. Moreover, only ERK2 is required for optimal androgen dependent induction of PSA, but optimal induction of TMPRSS2 requires both ERK1 and ERK2 [22]. Thus, an accurate assessment of AR activity requires measurement of a battery of target genes.

Overall expression of SRA in AR positive and AR negative prostate cancer cell lines is equivalent (figure 4) although the expression of individual splice variants may differ. Our finding that SRA contributes to growth of AR dependent LNCaP cells and to the growth of DU145 cells, but not PC-3 cells shows that SRA has both AR dependent and AR independent actions that can regulate growth.

It has been shown that RAC-3 can promote prostate cancer progression through AR unrelated mechanisms. We have shown here that RAC3 is also important for optimal AR signaling. We also show that SRA has an androgen independent role in proliferation as well as affecting AR signaling. According to our results SRA and RAC3 have different ligand requirements for AR coactivation, which suggest both different interaction surfaces and functional interactions. Our findings indicate that in response to different ligand treatments AR assembles distinct coregulator complexes to regulate transcription of individual target genes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank William E. Bingman III for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by NIH R01DK65252 (NLW), NIH P50-CA58204 SPORE in Prostate Cancer (NLW), DAMD 17-02-1-0012 (NLW) and T32HD07165 (IUA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Li R, Wheeler T, Dai H, Frolov A, Thompson T, Ayala G. High level of androgen receptor is associated with aggressive clinicopathologic features and decreased biochemical recurrence-free survival in prostate: cancer patients treated with radical prostatectomy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(7):928–34. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200407000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):33–9. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heemers HV, Tindall DJ. Androgen receptor (AR) coregulators: a diversity of functions converging on and regulating the AR transcriptional complex. Endocr Rev. 2007;28(7):778–808. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeh S, Miyamoto H, Shima H, Chang C. From estrogen to androgen receptor: a new pathway for sex hormones in prostate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(10):5527–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agoulnik IU, Vaid A, Bingman WE, 3rd, Erdeme H, Frolov A, Smith CL, et al. Role of SRC-1 in the promotion of prostate cancer cell growth and tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2005;65(17):7959–67. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agoulnik IU, Vaid A, Nakka M, Alvarado M, Bingman WE, 3rd, Erdem H, et al. Androgens modulate expression of transcription intermediary factor 2, an androgen receptor coactivator whose expression level correlates with early biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(21):10594–602. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou HJ, Yan J, Luo W, Ayala G, Lin SH, Erdem H, et al. SRC-3 is required for prostate cancer cell proliferation and survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65(17):7976–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan J, Yu CT, Ozen M, Ittmann M, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ. Steroid receptor coactivator-3 and activator protein-1 coordinately regulate the transcription of components of the insulin-like growth factor/AKT signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2006;66(22):11039–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanz RB, McKenna NJ, Onate SA, Albrecht U, Wong J, Tsai SY, et al. A steroid receptor coactivator, SRA, functions as an RNA and is present in an SRC-1 complex. Cell. 1999;97(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80711-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanz RB, Chua SS, Barron N, Soder BM, DeMayo F, O’Malley BW. Steroid receptor RNA activator stimulates proliferation as well as apoptosis in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(20):7163–76. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7163-7176.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agoulnik IU, Krause WC, Bingman WE, 3rd, Rahman HT, Amrikachi M, Ayala GE, et al. Repressors of androgen and progesterone receptor action. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(33):31136–48. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nazareth LV, Weigel NL. Activation of the human androgen receptor through a protein kinase A signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(33):19900–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onate SA, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270(5240):1354–7. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillatt D. Antiandrogen treatments in locally advanced prostate cancer: are they all the same? J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132 (Suppl 1):S17–26. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0133-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyamoto H, Yeh S, Wilding G, Chang C. Promotion of agonist activity of antiandrogens by the androgen receptor coactivator, ARA70, in human prostate cancer DU145 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(13):7379–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatchell EC, Colley SM, Beveridge DJ, Epis MR, Stuart LM, Giles KM, et al. SLIRP, a small SRA binding protein, is a nuclear receptor corepressor. Mol Cell. 2006;22(5):657–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watanabe M, Yanagisawa J, Kitagawa H, Takeyama K, Ogawa S, Arao Y, et al. A subfamily of RNA-binding DEAD-box proteins acts as an estrogen receptor alpha coactivator through the N-terminal activation domain (AF-1) with an RNA coactivator, SRA. Embo J. 2001;20(6):1341–52. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Shi Y, Downes M, Xie W, Kao HY, Ordentlich P, Tsai CC, et al. Sharp, an inducible cofactor that integrates nuclear receptor repression and activation. Genes Dev. 2001;15(9):1140–51. doi: 10.1101/gad.871201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawashima H, Takano H, Sugita S, Takahara Y, Sugimura K, Nakatani T. A novel steroid receptor co-activator protein (SRAP) as an alternative form of steroid receptor RNA-activator gene: expression in prostate cancer cells and enhancement of androgen receptor activity. Biochem J. 2003;369(Pt 1):163–71. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Sun XW, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310(5748):644–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Cai Y, Ren C, Ittmann M. Expression of variant TMPRSS2/ERG fusion messenger RNAs is associated with aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(17):8347–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agoulnik IU, Bingman WE, 3rd, Nakka M, Li W, Wang Q, Liu XS, et al. Target gene-specific regulation of androgen receptor activity by p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22(11):2420–32. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]