Summary

The mammalian secondary palate arises by outgrowth from the oral side of the paired maxillary processes flanking the primitive oral cavity. Palatal growth depends on reciprocal interactions between the oral ectoderm and the underlying neural-crest-derived mesenchyme. Previous studies have implicated sonic hedgehog (Shh) as an important epithelial signal for regulating palatal growth. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms through which Shh regulates palatal development in vivo have not been directly analyzed, due in part to early embryonic lethality of mice lacking Shh or other essential components of the Shh signaling pathway. Using Cre/loxP-mediated tissue-specific inactivation of the smoothened (Smo) gene in the developing palatal mesenchyme, we show that the epithelially expressed Shh signals directly to the palatal mesenchyme to regulate palatal mesenchyme cell proliferation through maintenance of cyclin D1 (Ccnd1) and Ccnd2 expression. Moreover, we show that Shh-Smo signaling specifically regulates the expression of the transcription factors Foxf1a, Foxf2 and Osr2 in the developing palatal mesenchyme. Furthermore, we show that Shh signaling regulates Bmp2, Bmp4 and Fgf10 expression in the developing palatal mesenchyme and that specific inactivation of Smo in the palatal mesenchyme indirectly affects palatal epithelial cell proliferation. Together with previous reports that the mesenchymally expressed Fgf10 signals to the palatal epithelium to regulate Shh mRNA expression and cell proliferation, these data demonstrate that Shh signaling plays a central role in coordinating the reciprocal epithelial-mesenchymal interactions controlling palatal outgrowth.

Keywords: Cleft palate, Fgf10, Osr2, Osr2-IresCre, Palate development, Shh, Smo, Tissue-specific gene inactivation

INTRODUCTION

The secondary palate arises from the medial side of the maxillary processes flanking the embryonic oral cavity. In mammals, the palatal processes initially grow vertically down the sides of the developing tongue. At a precise developmental stage the bilateral palatal shelves elevate to a horizontal position above the dorsum of the tongue and fuse with each other at the midline to form the intact secondary palate that separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity (Ferguson, 1988). Disturbances of the growth, elevation or fusion of the palatal shelves result in cleft palate, one of the most common birth defects in humans.

Classic organ culture assays and recent palatal explant studies with exogenous recombinant signaling molecules have demonstrated that growth and patterning of the developing palatal shelves depend on epithelial-mesenchymal interactions (Tyler and Koch, 1977; Ferguson and Honig, 1984; Zhang et al., 2002; Rice et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2005). During early palate development, expression of several signaling molecules and transcription factors, including Bmp4, Fgf10, Msx1 and Shox2, was found specifically restricted in the anterior palate (Zhang et al., 2002; Alappat et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2005) (reviewed by Hilliard et al., 2005). Bmp4 and Msx1 appeared to function in a positive feedback loop to regulate mesenchyme proliferation in the anterior palate (Zhang et al., 2002). In addition, mesenchymal Bmp4 was required to maintain Shh expression in the anterior palatal epithelium (Zhang et al., 2002) and exogenous Shh protein was capable of stimulating palatal mesenchyme proliferation in palate explant cultures (Zhang et al., 2002; Rice et al., 2004). The mesenchymally expressed Fgf10 regulates palatal epithelial cell survival and proliferation (Rice et al., 2004; Alappat et al., 2005). Both Fgf10 and its epithelial receptor Fgfr2b are also required for maintenance of Shh expression in the palatal epithelium (Rice et al., 2004). These data suggest that Shh plays important roles in palatal growth and patterning.

Shh is a member of the hedgehog family of secreted proteins and plays crucial roles in diverse developmental processes, including left-right axis establishment, dorsoventral patterning of the neural tube, endoderm development, anteroposterior patterning of the developing limb, and brain development and patterning (reviewed by Ingham and McMahon, 2001; McMahon et al., 2003; Roessler and Muenke, 2003). Shh signals to recipient cells through binding to the patched family of receptors, Ptch1 or Ptch2. In the absence of ligands, the patched receptors inhibit the function of another transmembrane protein, smoothened (Smo), an obligatory component of the hedgehog signaling pathway. Activation of Smo upon Shh signaling leads to activation of downstream genes by the Gli family transcription factors. Interestingly, Ptch1 and Gli1 are also among the downstream target genes of the Shh pathway, thus establishing a regulatory feedback loop (reviewed by Ingham and McMahon, 2001; McMahon et al., 2003).

Shh signaling plays essential roles in craniofacial development. Mutations in SHH in humans cause holoprosencephaly (reviewed by Cohen, 2004), whereas a targeted null mutation in Shh in mice resulted in severe cranial deficiencies (Chiang et al., 1996). Inhibition of Shh signaling in the chick facial primordia with a function-blocking antibody inhibited facial outgrowth, whereas ectopic application of active Shh protein caused facial overgrowth (Hu and Helms, 1999). Ahlgren and Bronner-Fraser showed that inhibition of Shh in the cranial mesenchyme caused extensive cell death (Ahlgren and Bronner-Fraser, 1999). Thus, Shh signaling appears to regulate both proliferation and survival of the neural-crest-derived cranial mesenchyme. However, the severe cranial deficiency in Shh null mutants and early embryonic lethality of mutant mouse embryos lacking either Ptch1 or Smo prevented a direct genetic analysis of the molecular mechanisms involving Shh signaling in palate development (Chiang et al., 1996; Goodrich et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 2001).

The adaptation of the Cre/loxP system for temporally and/or spatially controlled gene inactivation in mice made it possible to systematically dissect the genetic pathways in specific developmental processes (Jiang and Gridley, 1997; Sauer, 1998). Whereas mice homozygous for null mutations in Shh failed to develop most facial structures (Chiang et al., 1996), the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mice, in which Shh was inactivated specifically in epithelial cells after embryonic day 11.5 (E11.5), developed most facial structures but exhibited tooth developmental arrest (Dassule et al., 2000). The K14-Cre transgenic mice also expressed Cre in the oral epithelium, including in the palatal epithelium, during palatal outgrowth (Dassule et al., 2000; Vaziri Sani et al., 2005). About 85% of the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mice had cleft palate (Rice et al., 2004; Gritli-Linde, 2007). Unfortunately, there has been no report regarding palate development in the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice other than the brief descriptions of the late-term cleft palate phenotype. Similarly, while mice lacking Gli2 and mice with neural-crest-specific inactivation of Smo have been reported to have palatal defects (Mo et al., 1997; Jeong et al., 2004), how the Shh signaling pathway regulates palate development remains to be elucidated. Here we show, through analysis of mice with specific inactivation of Smo in the palatal mesenchyme, that Shh signaling regulates expression of a number of signaling molecules and transcription factors in the palatal mesenchyme to coordinate the epithelial-mesenchymal interactions that control palatal outgrowth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse strains

The Osr2-IresCre mice have been recently described (Lan et al., 2007). Shh+/n (Shhtm1Amc/J), Shhc/c (Shhtm2Amc/J) and Smoc/c (Smotm2Amc/J) mice have been described previously (St-Jacques et al., 1998; Dassule et al., 2000; Lewis et al., 2001; Long et al., 2001) and were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The R26R reporter mice (Soriano, 1999) were also purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. K14-Cre transgenic mice (line 43) (Andl et al., 2004) were acquired through a Material Transfer Agreement with Dr Sarah Millar at the University of Pennsylvania and provided by Dr Yang Chai (University of Southern California). K14-Cre transgenic mice were maintained by crossing to C57BL/6J mice. Shh+/n mice were also maintained by crossing to the C57BL/6J mice, whereas Shhc/c, Smoc/c and Osr2-IresCre mice were maintained as homozygotes in their own strain background. Male K14-Cre transgenic mice were crossed to Shh+/n female mice to generate K14-Cre;Shh+/n males, which were subsequently crossed to Shhc/c mice to generate K14-Cre;Shhc/n embryos for analysis. Independently, Osr2IresCre/IresCre homozygous male mice were crossed to Smoc/c female mice to generate Osr2-IresCre;Smo+/c male mice, which were subsequently crossed to Smoc/c female mice to generate Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c embryos for analysis. Although the Ires-Cre insertion in the Osr2IresCre allele did not disrupt Osr2 gene function (Lan et al., 2007), all experimental analysis of Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c embryos used Osr2-IresCre;Smo+/c littermates as controls. Genotyping of mice and embryos were carried out by allele-specific PCR as previously described (Dassule et al., 2000; Long et al., 2001; Lan et al., 2007).

Histology and in situ hybridization analyses

For histology, embryos were fixed in Bouin's fixative, dehydrated through graded alcohols, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 7 μm thickness, and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin. For in situ hybridization, embryos were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, dehydrated through graded alcohols, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 μm thickness. In situ hybridization of tissue sections were performed as described previously (Zhang et al., 1999). At least three pairs of control and mutant embryos were analyzed for each developmental stage.

X-gal staining and skeletal analysis

Embryos were dissected in ice-cold PBS and stained with X-gal for β-galactosidase detection as described previously (Hogan et al., 1994). Cryosections were counterstained with Eosin following X-gal staining. Skeletal preparations were made from newborn mice as described previously (Martin et al., 1995).

Detection of cell proliferation and immunohistochemical staining

For detection of cell proliferation in the palatal shelves, timed pregnant female mice were injected intraperitoneally on gestational day 12.5 or 13.5 with BrdU (Roche) labeling reagent (45 μg/g body weight). One hour after injection, embryos were dissected, fixed, embedded in paraffin and sectioned in the coronal plane for immunodetection of BrdU using the BrdU labeling and detection kit (Roche) as described previously (Lan et al., 2004). Following BrdU immunostaining, the embryonic sections were counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red to visualize all cellular nuclei. Sections were selected from the middle of the anterior halves (corresponding to the anterior margin of the maxillary first molar tooth buds) and posterior regions (posterior to the maxillary first molar tooth buds) of the palatal shelves in comparable positions in the control and mutant embryos. Cell counts were recorded separately for the palatal epithelium and mesenchyme in each of the bilateral palatal shelves from five continuous sections of each region of the palate. The cell proliferation index was calculated as a percentage of the cell nuclei with BrdU labeling. Data were collected from at least three pairs of mutant and control littermates. Students' t-test was used to analyze the significance of difference and a P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Immunohistochemical detection of cyclin D1 was carried out with paraffin sections of paraformaldehyde-fixed embryos using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against cyclin D1 (Thermo Scientific, Fremont, CA) at 1:200 dilution and detected using the Zymed Histostain Plus Kit (Zymed Laboratories) as previously described (Casey et al., 2006).

RESULTS

K14-Cre mediated inactivation of Shh in the palatal epithelium does not completely abrogate Shh signaling during palatal outgrowth

It has been reported that K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice exhibited incomplete penetrance of cleft palate in mice (Rice et al., 2004; Gritli-Linde, 2007). To investigate the roles of Shh signaling in palate development, we generated K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice using a different K14-Cre transgenic mouse line (line 43) (Andl et al., 2004) from that used in the previous studies, hoping to achieve higher penetrance of the cleft palate phenotype. However, we observed that about 70% (12 of 17) of our K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice exhibited cleft palate (Fig. 1B; and data not shown). To examine whether Shh signaling plays a crucial role in palatal outgrowth, we first compared cell proliferation during early palate development in four pairs of K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant and control littermates by examining BrdU incorporation at E13.5. Of the four K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant embryos, one displayed significant reduction in the numbers of BrdU-labeled cells in both the palatal epithelium and mesenchyme (Fig. 1C,D), one displayed significant reduction in BrdU-labeled cells in the epithelium only, one displayed reduction in BrdU-labeled cells in the palatal mesenchyme only and one had similar cell proliferation in both the palatal epithelium and mesenchyme to that in the control embryos (see Table S1 in the supplementary material). These data suggest that the inactivation of Shh in the palatal epithelium may be variable in the different K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice.

Fig. 1.

Partial inactivation of Shh in the developing palate in K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice. (A,B) Frontal sections of E17.5 K14-Cre;Shhc/+ (A) and K14-Cre;Shhc/n (B) mutant mouse heads showing cleft palate in the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant. Arrowheads point to palatal shelves, and the asterisk in B marks the cleft between the bilateral palatal shelves in the mutant. (C,D) At E13.5, the percentage of BrdU-labeled cells are reduced in the palatal epithelium and mesenchyme in some K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant embryos (D) in comparison with K14-Cre;Shhc/+ littermates (C). White arrows point to the first molar tooth buds in which cell proliferation is also reduced in the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant embryo in comparison with K14-Cre;Shhc/+ littermate. (E,F) Ptch1 mRNA expression is reduced in the oral epithelium and palatal mesenchyme in K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant embryos (F) in comparison with K14-Cre;Shhc/+ littermates (E). (G,H) Gli1 mRNA expression was also downregulated in the oral epithelium and palatal mesenchyme in the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant embryos (H) in comparison with K14-Cre;Shhc/+ littermates (G) at E13.5. BrdU staining and mRNA signals were detected in blue. Black arrows in E-H point to the maxillary molar tooth buds. oc, mandibular ossification center; p, palatal shelf; t, tongue.

To examine the efficiency of Shh inactivation in the palatal epithelium in K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice, we compared expression of Ptch1 and Gli1, two known target genes of Shh signaling, in the developing palatal shelves in the mutant and control littermates. At E13.5, both Ptch1 and Gli1 are expressed in a lateral-to-medial gradient in the mesenchyme of the developing palatal shelves in the control embryos (Fig. 1E,G). In the E13.5 K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant embryos, expression of both Ptch1 and Gli1 in the developing palatal shelves is downregulated but substantial amounts of Ptch1 and Gli1 mRNAs remained in the palatal mesenchyme in all three mutant embryos examined (Fig. 1F,H). By contrast, expression of both mRNAs is nearly completely downregulated in the developing tooth epithelium in the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant embryos in comparison with control littermates (Fig. 1E-H). Both Ptch1 and Gli1 are also highly expressed in the mesenchymal cells in the mandibular ossification areas, which are regulated by Ihh instead of Shh and are not altered in the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant embryos (Fig. 1E-H). As Shh expression has been detected only in the palatal epithelium but not in the palatal mesenchyme (Zhang et al., 2002; Rice et al., 2006), and as Ihh expression is restricted to the areas undergoing ossification whereas Dhh is not expressed in the developing palate (Rice et al., 2006), the sustained expression of Ptch1 and Gli1 in the palatal mesenchyme indicates that the inactivation of Shh in the palatal epithelium in the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant embryos was incomplete, which is the most likely reason for the great variability in palatal mesenchyme proliferation at E13.5 and the incomplete penetrance of the cleft palate phenotype at birth.

Shh signals directly to the mesenchyme to regulate palatal outgrowth

To further investigate the molecular mechanisms involving Shh-Smo signaling in the epithelial-mesenchymal interactions regulating palate development, we decided to analyze mice with inactivation of Smo in the palatal mesenchyme using the recently generated Osr2-IresCre knockin mice (Lan et al., 2007). The Osr2-IresCre mice express Cre recombinase in the palatal mesenchyme from the onset of palatal outgrowth at E11.5 (Lan et al., 2007) (Fig. 2A). Importantly, although Osr2-IresCre mice express Cre in several other tissues in the developing craniofacial complex (Lan et al., 2007) (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material), Cre activity was restricted in the mesenchyme and was not detected in the epithelium of the developing secondary palate (Fig. 2B). In the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c embryos, whereas Ptch1 and Gli1 were expressed in the palatal epithelial cells and several other craniofacial tissues at similar levels to those in control littermates (see Fig. S2A-D in the supplementary material), expression of both genes was dramatically downregulated in the palatal mesenchyme by E13 (Fig. 2C-F). These data demonstrate that signaling downstream of Shh remained intact in the palatal epithelium and was efficiently blocked in the palatal mesenchyme in Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos. Examination of Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant pups at birth revealed that 100% (n=22) of them had cleft palate (Fig. 3), indicating that Shh signaling in the palatal mesenchyme is required for palate development. In addition to the cleft palate defect, the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant mice exhibited open eyelids and smaller but thickened tympanic rings (Fig. 3B,F). As neither the Osr2-IresCre heterozygous mice nor the Osr2-IresCre;Smo+/c mice had these defects (Fig. 3A,C,E; and data not shown), they probably resulted from loss of Smo-mediated hedgehog signaling in the developing eyelids and other craniofacial tissues where Cre was also expressed (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). Consistent with this hypothesis, expression of both Ptch1 and Gli1 was also downregulated in the developing eyelid tissues in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant mice, in comparison with the control littermates (see Fig. S2A-D in the supplementary material).

Fig. 2.

Osr2-IresCre-mediated inactivation of Smo efficiently blocks Hedgehog signaling in the palatal mesenchyme by E13. (A) Whole-mount X-gal staining of an E11.5 Osr2-IresCre;R26R embryo showing specific Cre-mediated activation of lacZ expression in the primordia of the primary (arrowheads) and secondary (arrows) palate. Asterisks mark the sites of fusion between the medial nasal and the maxillary processes. (B) X-gal stained frontal section of E12.5 Osr2-IresCre;R26R embryo showing β-galactosidase activity throughout the palatal mesenchyme but absent in the palatal epithelium (arrowheads). (C,D) By E13.0, Ptch1 mRNA expression was dramatically downregulated in the palatal mesenchyme and persisted in the palatal epithelium (arrowhead) in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c embryo (D) in comparison with control littermate (C). (E,F) Gli1 mRNA expression was also dramatically downregulated in the palatal mesenchyme and persisted in the palatal epithelium (arrowhead) in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryo (F) in comparison with the control littermate (E) by E13.0. lnp, lateral nasal process; max, maxillary process; mnp, medial nasal process; p, palatal shelf; t, tongue. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Fig. 3.

Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant mice exhibit cleft palate and open eyelids at birth. (A,B) Neonatal control (A) and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant (B) mice showing open eyelids (arrow) at birth in the mutant. (C,D) Frontal sections of E17.5 control (C) and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant (D) embryos showing cleft palate in the mutant. (E,F) Skeletal preparations of control (E) and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant (F) neonatal mice showing widely separate palatine bones (arrows) in the mutant. The insets show high magnification views of the tympanic rings (arrowheads) in the Osr2-IresCre;Smo+/c (E) and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant (F) skeletons. Bones are stained red and cartilage blue. The asterisk in F marks the presphenoid bone of the cranial base, which is hidden under the palatine bones from the oral view of the skeleton in the control mouse in E but fully exposed in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant skeleton due to cleft palate. n, nasal septum; p, palatal shelf; t, tongue.

Cell proliferation is reduced in both the mesenchyme and epithelium in the developing palatal shelves of Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutants

To clarify the role of Shh-Smo signaling in the palatal mesenchyme, we carried out histological analyses of embryos throughout palate development from E12 to E16. As shown in Fig. 4, initial palatal growth was normal in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutants by E12.5 (Fig. 4A,B). When examined at E13.5, the palatal shelves of the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos appeared slightly retarded (Fig. 4D) compared with the control littermates (Fig. 4C). At E14.5, the palatal shelves had elevated and initiated fusion at the midline in the control embryos (Fig. 4E), whereas the palatal shelves in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant littermates were significantly retarded and failed to make contact (Fig. 4F). In some Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos, in addition to palatal shelf retardation, there was aberrant tissue morphogenesis associated with the nasopharynx and the developing tongue (Fig. 4H).

Fig. 4.

Histological analyses of palate development in the control and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos. (A,B) HE-stained frontal sections of E12.5 Osr2-IresCre;Smo+/c (A) and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant (B) embryos showed comparable initial outgrowth of palatal shelves. (C,D) At E13.5, the palatal shelves of the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryo (D) appeared slightly retarded distally in comparison with the Osr2-IresCre;Smo+/c embryo (C). (E,F) At E14.5, whereas the palatal shelves had elevated and initiated fusion at the midline in the control embryo (E), the palatal shelves of the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryo (F) appeared severely retarded and failed to contact each other. (G,H) Some Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos exhibited tissue protrusion into the nasopharynx, shown in H (marked by an asterisk), which was never observed in control embryos. p, palatal shelf; t, tongue.

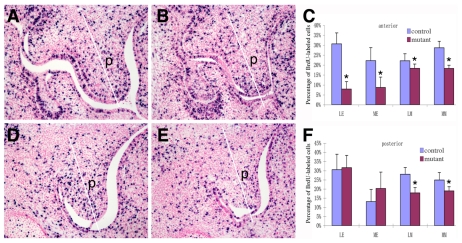

To investigate whether palatal shelf retardation in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos was due to impaired cell proliferation, we analyzed BrdU incorporation in E13 embryos. Indeed, the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutants consistently exhibited significant reductions in cell proliferation throughout the anteroposterior axis in the palatal mesenchyme (Fig. 5). Interestingly, the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos also exhibited significant reduction in cell proliferation in the anterior, but not in the posterior, palatal epithelia (Fig. 5C,F). As these embryos had Smo inactivation in the palatal mesenchyme but not in the palatal epithelium, the significant reduction in cell proliferation in the anterior palatal epithelium suggests that Shh-Smo signaling controls expression of mesenchymal factors involved in the regulation of palatal epithelial proliferation.

Fig. 5.

Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos exhibited defects in palatal shelf growth at E13.5. Frontal sections through the palatal regions of BrdU-labeled Osr2-IresCre;Smo+/c (A,D) and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant (B,E) embryos were stained with anti-BrdU antibody. The labeled cell nuclei were stained blue. The white line in each panel divided each image of the palatal shelf to medial and lateral halves for the calculation of the percentage of BrdU-labeled nuclei in those regions separately. A and B show typical sections through the middle of the anterior half of the palatal shelves, whereas D and E are from the posterior third of the palatal shelves. (C,F) Comparison of the percentage of BrdU-labeled cells in the anterior (C) and posterior (F) regions of the developing palate in the Osr2-IresCre;Smo+/c (control) and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c (mutant) embryos. Standard deviation values were used for the error bars. An asterisk denotes a significant reduction in the percentage of BrdU-labeled cells in the mutant (P<0.05). p, palatal shelf.

Expression of cyclin D1 and cyclin D2 is downregulated in the developing palatal mesenchyme in Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutants

Shh signaling has been shown to regulate cell proliferation during many developmental processes through modulation of cyclin D1 (Ccnd1) or Ccnd2 expression (Kenney and Rowitch, 2000; Ishibashi and McMahon, 2002; Lobjois et al., 2004; Mill et al., 2005; Hu et al., 2006). Immunohistochemical staining using a Ccnd1-specific antibody showed that it is strongly expressed in both the palatal epithelium and mesenchyme at E13.5 in control embryos (Fig. 6A). Expression of Ccnd1 was substantially diminished in the palatal mesenchyme in Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant littermates (Fig. 6B). Ccnd2 is expressed strongly in the palatal epithelium and relatively weakly throughout the palatal mesenchyme in control embryos at E13.5 (Fig. 6C). In the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos, whereas Ccnd2 mRNA expression in the palatal epithelium was similar to that in the control embryos, its expression in the palatal mesenchyme was clearly reduced (Fig. 6D). Thus, Shh signaling regulates palatal mesenchyme cell proliferation at least in part through the maintenance of Ccnd1 and Ccnd2 expression.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of Ccnd1 protein and Ccnd2 mRNA expression in the developing palate in control and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos at E13.5. (A,B) Ccnd1 immunostaining (shown in brown) in frontal sections of control (A) and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant (B) embryos. Ccnd1 expression in the tooth bud epithelium (arrows) served as internal controls because Osr2-IresCre was not expressed in this tissue. Arrowheads point to the palatal epithelium, which appeared thinner in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos than in the control littermates. (C,D) In situ hybridization detection of Ccnd2 mRNA (in blue) in frontal sections of control (C) and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant (D) embryos. p, palatal shelf.

Alterations in Bmp2 and Bmp4 expression in the developing palatal mesenchyme of Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos

In palatal explant culture assays, exogenous Shh protein induced Bmp2 but not Bmp4 mRNA expression in the anterior palate (Zhang et al., 2002). In E13.5 wild-type embryos, both Bmp2 and Bmp4 mRNAs are expressed in the distal mesenchyme underlying the medial edge epithelium in the anterior palate, and neither is expressed in the posterior palatal mesenchyme (Zhang et al., 2002; Hilliard et al., 2005). Bmp2 mRNA expression in the palatal mesenchyme was downregulated in Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos in comparison with that in control littermates (Fig. 7A,B), confirming the hypothesis that Shh-Smo signaling is required for maintenance of Bmp2 mRNA expression in the anterior palatal mesenchyme in vivo. However, Bmp4 expression in the anterior palatal mesenchyme was upregulated, particularly in the lateral region of the anterior palatal mesenchyme, in Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos compared with control littermates (Fig. 7C,D). Expression of Msx1, a known downstream target of Bmp4 signaling, was also upregulated in the anterior palatal mesenchyme in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos (Fig. 7E,F). By contrast, expression of Shox2, encoding a transcription factor specifically expressed in and required for development of the anterior palate (Yu et al., 2005), was not significantly altered in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos compared with control littermates (Fig. 7G,H), indicating that the effects of Smo inactivation on the expression of Bmp2, Bmp4 and Msx1 in the palatal mesenchyme are specific and not due to tissue retardation.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of Bmp2, Bmp4, Msx1 and Shox2 mRNA expression in the anterior palate of Osr2-IresCre;Smo+/c and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos at E13.5. (A-F) In comparison with the control embryos, Bmp2 mRNA was downregulated whereas Bmp4 and Msx1 mRNAs were upregulated in the mutant anterior palatal mesenchyme. Arrowheads point to differences in expression in the control (A,C,E) and mutant (B,D,F) palatal shelves. (G,H) Shox2 mRNA expression was unaltered in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant palate. p, palatal shelf; t, tongue.

Downregualtion of expression of Foxf1, Foxf2 and Osr2 in the palatal mesenchyme of Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos

Shh-Smo signaling has been shown to directly regulate the expression of several members of the Forkhead Box (Fox) family of transcription factors, including Foxc2, Foxd1, Foxd2, Foxf1a and Foxf2, during early craniofacial development (Jeong et al., 2004). To better understand the Shh signaling pathway in palate development, we examined expression of these Fox genes in the developing palatal shelves in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos and control littermates. Expression of Foxc1, Foxc2 and Foxd2 was absent or very weak in the control palatal mesenchyme at E13.5 and was not altered in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant littermates (data not shown). Foxf1a mRNA was highly specifically expressed in the lateral palatal mesenchyme as well as in the lingual side of the molar tooth mesenchyme in the E13.5 control embryos (Fig. 8A,C). In the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c littermates, Foxf1a mRNA expression was specifically downregulated in the palatal mesenchyme in both the anterior and posterior palate, whereas its expression in the tooth mesenchyme persisted (Fig. 8B,D). Foxf2 mRNA was highly expressed in the palatal mesenchyme and in the developing tongue musculature at E13.5 in control embryos (Fig. 8E,G). Expression of Foxf2 mRNA was specifically downregulated in the palatal mesenchyme, whereas strong expression persisted in the developing tongue, in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c littermates (Fig. 8F,H). Thus, similar to that in the early developing facial primordia, expression of Foxf1a and Foxf2 in the developing palatal mesenchyme is also positively regulated by Shh-Smo signaling.

Fig. 8.

Foxf1 and Foxf2 mRNA expression in the developing palate were downregulated in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos. (A) At E13.5, Foxf1a mRNA was expressed in the anterior palatal mesenchyme underlying the lateral and medial edge epithelium (arrow) in the control embryos. (B) Foxf1a mRNA expression was specifically downregulated in the palatal mesenchyme but its expression in the tooth mesenchyme was not affected in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos. Asterisks in A and B mark the maxillary first molar tooth buds. (C,D) At E13.5, Foxf1 mRNA expression in the posterior palate was restricted to more lateral and proximal cells in the control embryo (C) and this domain of expression (arrows in C and D) was also downregulated in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos (D). (E-H) Foxf2 mRNA expression exhibited a lateral-to-medial gradient in both the anterior and posterior palate in the control embryos (E,G) and was downregulated in both the anterior and posterior palatal mesenchyme in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos (F,H). E and F show anterior palates; G and H, posterior. p, palatal shelf; t, tongue.

To further investigate the molecular mechanisms of Shh-Smo signaling in palate development, we compared expression of several other mesenchymal transcription factors known to regulate palate development. Osr2 encodes a zinc finger protein specifically required for palatal mesenchyme cell proliferation (Lan et al., 2001; Lan et al., 2004). Whereas Osr2 mRNA expression was similar in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant and control embryos at E12.5 (data not shown), there was a significant reduction in Osr2 mRNA expression in the palatal mesenchyme in Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos by E13.5 (Fig. 9A,B). By contrast, Osr2 mRNA expression in the mesenchyme lingual to the first molar tooth buds remained at similar levels in the control and mutant littermates (Fig. 9A,B). Moreover, expression of three other transcription factor genes, Osr1, Pax9 and Tbx22, were not significantly altered in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant palate from that in the control littermates (Fig. 9C,D; and data not shown). Thus, Smo activity appears to be specifically required for the maintenance of Osr2 mRNA expression in the palatal mesenchyme.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of expression of Osr2, Pax9 and Fgf10 in the developing palate of the control and Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos. (A) At E13.5, Osr2 mRNA was strongly expressed in the mesenchyme lingual to the first molar tooth buds and exhibited a lateral-to-medial gradient in the palatal mesenchyme in control embryos. (B) In the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos at E13.5, Osr2 mRNA expression was specifically downregulated in the palatal mesenchyme but the domain of expression in the lingual tooth mesenchyme was unaffected. (C,D) Pax9 mRNA expression in the developing palate and tooth mesenchyme was not affected in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos. (E,F) Fgf10 expression in the anterior palatal mesenchyme (arrows) was significantly downregulated in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos (F) in comparison with the control embryos (E). m, mandibular first molar tooth bud; p, palatal shelf.

Shh-Smo signaling is required for maintenance of Fgf10 expression in the palatal mesenchyme

Fgf10 is expressed in the palatal mesenchyme and regulates palatal epithelial cell proliferation (Rice et al., 2004). Interestingly, Fgf10 mRNA is strongly expressed in the anterior half, with little expression in the posterior half, of the developing palatal shelves (Alappat et al., 2005; Welsh et al., 2007). We found that Fgf10 mRNA expression in the developing anterior palatal mesenchyme was dramatically reduced in Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos by E13.5, in comparison with control littermates (Fig. 9E,F). Interestingly, Fgf10 expression was also downregulated in the developing eyelid mesenchyme in Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos, in comparison with the control littermates (see Fig. S2E,F in the supplementary material). Expression of Fgf10 in both the developing palate and eyelid overlapped with that of Ptch1, and the downregulation of Fgf10 expression also correlated with downregulation of Ptch1 in these tissues, in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos (Fig. S2A,B,E,F in the supplementary material). Fgf10 also plays a crucial role in regulating cell proliferation during eyelid development (Tao et al., 2005). Similar to Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant mice, K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice exhibited open eyelids at birth (Dassule et al., 2000). Taken together, these data suggest that Fgf10 acts downstream of Shh signaling to regulate development of the eyelid and secondary palate.

DISCUSSION

Despite significant advances in understanding of the molecular basis of palate development in recent years (reviewed by Gritli-Linde, 2007), it is not known what signals induce initial palatal outgrowth and how various molecular pathways are integrated to regulate the epithelial-mesenchymal interactions controlling palatal growth. Shh is expressed in the oral epithelium before palatal outgrowth and becomes restricted to the medial and lateral epithelium of the downward-growing palatal shelves (Rice et al., 2006). In palatal explant culture assays, exogenous Shh protein increased palatal mesenchyme cell proliferation, and a function-blocking Shh antibody inhibited palatal mesenchyme proliferation (Zhang et al., 2002). Whereas targeted null mutations in the Shh gene resulted in severe craniofacial defects in homozygous mutant mice, K14-Cre-mediated inactivation of Shh in epithelial tissues, including oral ectoderm, caused incomplete penetrance of cleft palate (Rice et al., 2004; Gritli-Linde, 2007). We found that the incomplete penetrance of cleft palate in the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice was due to incomplete inactivation of Shh activity in the palatal epithelium. The different K14-Cre transgenic mouse strains resulted in different penetrance of the cleft palate phenotype in the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice, probably due to transgene positional effects and different mouse strain background effects on Cre expression.

In this study, we used the recently generated Osr2-IresCre knockin mice to genetically dissect the molecular mechanism involving Shh signaling in palate development. Although the Osr2-IresCre mice also express Cre in several other craniofacial tissues (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material), they express Cre throughout the palatal mesenchyme but not in the palatal epithelium (Fig. 2B). Indeed, we found that the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos exhibited dramatic reduction in expression of Ptch1 and Gli1 mRNAs in the palatal mesenchyme by E13. Interestingly, although Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant mice exhibited complete penetrance of cleft palate, their palatal shelves appeared morphologically normal before E13 and were elevated by E14.5, in contrast to the previously described severely retarded palatal shelves that failed to elevate in the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice (Rice et al., 2004; Gritli-Linde, 2007). These differences in palatal phenotype may be due to loss of Shh signaling in both the epithelium and mesenchyme in the K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant mice compared with loss of Shh signaling only in the palatal mesenchyme in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant mice. It is also possible that the high penetrance of cleft palate phenotype in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant mice resulted from a combination of palatal specific defects and secondary effects of loss of Smo in other Cre-expressing craniofacial tissues. Nevertheless, the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant mice provided an opportunity to clarify the role of Shh signaling in the reciprocal epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during palate development.

The epithelially expressed Shh signals directly to the palatal mesenchyme to regulate palatal outgrowth

In palatal explant culture assays, Zhang et al. showed that exogenous Shh protein induced Bmp2, but not Bmp4, mRNA expression in the anterior palatal mesenchyme (Zhang et al., 2002). Zhang et al. further showed that both exogenous Shh and Bmp2 proteins induced palatal mesenchyme proliferation and that exogenous noggin protein blocked the effect of Shh on palatal mesenchyme proliferation (Zhang et al., 2002), which led to the hypothesis that Bmp2 mediated the mitogenic effect of Shh signaling on the palatal mesenchyme. Whereas our data confirm a role for Shh-Smo signaling in maintenance of Bmp2 expression in the anterior palatal mesenchyme, it should be noted that Bmp2 expression in the anterior palatal mesenchyme is highly restricted to just subjacent to the medial edge epithelium and at very low abundance compared with its abundant expression in many other regions of the developing craniofacial complex (see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material). Moreover, whereas Shh was shown to induce Bmp2 expression in the anterior but not the posterior palatal explants (Zhang et al., 2002), we found that mesenchymal cell proliferation was significantly reduced in both anterior and posterior regions of the developing palate in the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos, indicating that other factors also mediate the mitogenic effects of Shh signaling in the palatal mesenchyme. Furthermore, we found that the expression levels of Ccnd1 protein and of Ccnd2 mRNA were both reduced in the palatal mesenchyme of Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos, compared with the control littermates. Shh signaling has been shown to regulate Ccnd1 and/or Ccnd2 expression in multiple tissues and Gli proteins have been shown to bind to specific sites in the Ccnd1 and Ccnd2 gene promoters (Kenney and Rowitch, 2000; Long et al., 2001; Ishibashi and McMahon, 2002; Yoon et al., 2002; Mill et al., 2005; Hu et al., 2006). Gli1, Gli2 and Gli3 are all expressed in the palatal mesenchyme during palatal outgrowth (Rice et al., 2006). Thus, it is likely that Shh-Smo signaling directly activates Gli-mediated transcriptional activation of Ccnd1 and Ccnd2 in the palatal mesenchyme to promote palatal outgrowth.

Foxf1, Foxf2 and Osr2 may be downstream effectors of Shh signaling during palatal outgrowth

During early craniofacial development, expression of several Fox family genes, including Foxf1a and Foxf2, depended on Shh-Smo signaling (Jeong et al., 2004). Foxf1a expression in the developing lung mesenchyme, a non-neural-crest-derived tissue, was also positively regulated by Shh signaling (Mahlapuu et al., 2001a). We found that Foxf1a and Foxf2 were expressed in the developing palatal mesenchyme in the control embryos and both were downregulated in the palatal mesenchyme of the Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos. Whereas Foxf1a-/- null mouse embryos died before craniofacial morphogenesis, Foxf2-/- mutant mice exhibited complete cleft palate (Mahlapuu et al., 2001b; Wang et al., 2003). Jeong et al. proposed a Fox code for mediating the roles of Shh-Smo signaling during early facial development (Jeong et al., 2004). It is likely that Foxf1a and Foxf2 also mediate some of the effects of Shh-Smo signaling during palate development.

We found that Osr2 mRNA expression was downregulated in the palatal mesenchyme of Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant mouse embryos. Although Osr2 was not expressed in many tissues that receive active Shh signaling, such as in the ventral neural tube, Osr2 mRNA expression overlapped with Ptch1 mRNA expression during palate development, with each exhibiting a lateral-to-medial gradient as the palatal shelves grew vertically from E12 to E13.5 (Lan et al., 2001; Lan et al., 2004; Rice et al., 2006). To confirm that Shh signaling plays a role in the maintenance of Osr2 mRNA expression in the developing palatal mesenchyme, we examined Osr2 mRNA expression in K14-Cre;Shhc/n mutant embryos and found that it was also downregulated in the palatal mesenchyme in those embryos by E13.5 (data not shown). Osr2 is one of a few transcription factors with a proven role in regulating palatal mesenchyme cell proliferation (Lan et al., 2004). It is possible that Shh regulates palatal mesenchyme cell proliferation in part through maintenance of Osr2 expression.

Shh signaling coordinates the reciprocal epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during palatal outgrowth

We found that Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant mice exhibited significant reduction in cell proliferation in the anterior palatal epithelium. As Shh-Smo signaling remained intact in the palatal epithelium in these mutants, we hypothesized that Shh signaling controls the expression of a mesenchymal factor required for palatal epithelial cell proliferation. Rice et al. showed that Fgf10, expressed in the developing palatal mesenchyme, was required for palatal epithelial cell proliferation (Rice et al., 2004). Interestingly, Fgf10 is normally strongly expressed in the anterior half, with very little expression in the posterior half, of the developing palate (Alappat et al., 2005; Hilliard et al., 2005; Welsh et al., 2007). We found that expression of Fgf10 mRNA in the anterior palatal mesenchyme was dramatically downregulated in Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant embryos, suggesting that Shh-Smo signaling in the palatal mesenchyme secondarily affected palatal epithelial cell proliferation through regulation of Fgf10 expression.

Shh has been shown to regulate Fgf10 expression during development of several other vertebrate organs. Shh induced Fgf10 mRNA expression in the chick limb bud (Ohuchi et al., 1997). Exogenous Shh also induced, and a function blocking Shh antibody inhibited, Fgf10 mRNA expression in the developing genital tubercle mesenchyme (Haraguchi et al., 2001). We found, in addition to downregulation of Fgf10 in the palatal mesenchyme, Osr2-IresCre;Smoc/c mutant mice exhibited downregulation of Fgf10 expression in the developing eyelid mesenchyme. By contrast, Shh inhibited Fgf10 expression in the developing lung mesenchyme and Shh-/- mutant mice exhibited more widespread expression of Fgf10 mRNA in the developing lung mesenchyme (Bellusci et al., 1997; Litingtung et al., 1998). Thus, Fgf10 expression may be either positively or negatively regulated by Shh signaling depending on the specific developmental context. It is possible that similar effectors downstream of Shh-Smo signaling exist in the developing eyelid, palate, limb bud and genital tubercle mesenchyme for the maintenance of Fgf10 mRNA expression. Interestingly, Rice et al. showed that exogenous Fgf10 protein induced Shh mRNA expression in the palatal epithelium of wild-type embryos and that Shh mRNA expression was reduced in the palatal epithelium in Fgf10-/- and Fgfr2b-/- mutant embryos (Rice et al., 2004). Whereas our data indicate secondary effects of Smo inactivation in the palatal mesenchyme on palatal epithelial cell proliferation, Rice et al. showed that cell proliferation was significantly reduced not only in the palatal epithelium but also in the palatal mesenchyme in Fgf10-/- and Fgfr2b-/- mutant mice (Rice et al., 2004). Taken together, these data suggest that Shh and Fgf10 function in a positive feedback loop to regulate palatal outgrowth.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/136/8/1387/DC1

Supplementary Material

This work would not have been possible without the Shh+/n, Shhc/c and Smoc/c gene-targeted mouse strains generated and deposited into the Jackson Laboratory Mutant Mouse Resources by the McMahon Laboratory. We also thank Sarah Millar and Yang Chai for providing the K14-Cre transgenic mice, Peter Carlsson and Trish Labosky for cDNA probes, Kathleen Maltby and Qingru Wang for technical assistance, and Yang Gao for help with statistical analysis. This work was supported by a NIH/NIDCR grant R01DE013681 to R.J. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Ahlgren, S. C. and Bronner-Fraser, M. (1999). Inhibition of sonic hedgehog signaling in vivo results in craniofacial neural crest cell death. Curr. Biol. 9, 1304-1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alappat, S. R., Zhang, Z., Suzuki, K., Zhang, X., Liu, H., Jiang, R., Yamada, G. and Chen, Y. P. (2005). The cellular and molecular etiology of the cleft secondary palate in Fgf10 mutant mice. Dev. Biol. 277, 102-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andl, T., Ahn, K., Kairo, A., Chu, E. Y., Wine-Lee, L., Reddy, S. T., Croft, N. J., Cebra-Thomas, J. A., Metzger, D., Chambon, P. et al. (2004). Epithelial Bmpr1a regulates differentiation and proliferation in postnatal hair follicles and is essential for tooth development. Development 131, 2257-2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellusci, S., Grindley, J., Emoto, H., Itoh, N. and Hogan, B. L. (1997). Fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10) and branching morphogenesis in the embryonic mouse lung. Development 124, 4867-4878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey, L. M., Lan, Y., Cho, E. S., Maltby, K. M., Gridley, T. and Jiang, R. (2006). Jag2-Notch1 signaling regulates oral epithelial differentiation and palate development. Dev. Dyn. 235, 1830-1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, C., Litingtung, Y., Lee, E., Young, K. E., Corden, J. L., Wesphal, H. and Beachy, P. (1996). Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking Sonic hedgehog gene function. Nature 383, 407-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M. M. (2004). SHH and holoprosencephaly. In Inborn Errors of Development: The Molecular Basis of Clinical Disorders of Morphogenesis (ed. C. J. Epstein, R. P. Erickson and A. Wynshaw-Boris), pp. 240-248. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dassule, H. R., Lewis, P., Bei, M., Maas, R. and McMahon, A. (2000). Sonic hedgehog regulates growth and morphogenesis of the tooth. Development 127, 4775-4785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, M. W. J. (1988). Palate Development. Development 103, 41-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, M. W. J. and Honig, L. S. (1984). Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during vertebrate palatogenesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 19, 137-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, L. V., Milenkovic, L., Higgins, K. M. and Scott, M. P. (1997). Altered neural cell fates and medulloblastoma in mouse patched mutants. Science 277, 1109-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritli-Linde, A. (2007). Molecular control of secondary palate development. Dev. Biol. 301, 309-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi, R., Mo, R., Hui, C., Motoyama, J., Madino, S., Shiroishi, T., Gaffield, W. and Yamada, G. (2001). Unique functions of sonic hedgehog signaling during external genitalia development. Development 128, 4241-4250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard, S. A., Yu, L., Gu, S., Zhang, Z. and Chen, Y. P. (2005). Regional regulation of palatal growth and patterning along the anterior-posterior axis in mice. J. Anat. 207, 655-667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, B., Beddington, R., Costantini, F. and Lacy, E. (1994). Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Hu, D. and Helms, J. A. (1999). The role of sonic hedgehog in normal and abnormal craniofacial morphogenesis. Development 126, 4873-4884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M. C., Mo, R., Bhella, S., Wilson, C. W., Chuang, P. T., Hui, C. C. and Rosenblum, N. D. (2006). GLI3-dependent transcriptional repression of Gli1, Gli2 and kidney patterning genes disrupts renal morphogenesis. Development 133, 569-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, P. W. and McMahon, A. P. (2001). Hedgehog signaling in animal development: paradigms and principles. Genes Dev. 15, 3059-3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi, M. and McMahon, A. P. (2002). A sonic hedgehog-dependent signaling relay regulates growth of diencephalic and mesencephalic primordial in the early mouse embryo. Development 129, 4807-4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J., Mao, J., Tenzen, T., Kottmann, A. H. and McMahon, A. P. (2004). Hedgehog signaling in the neural crest cells regulates the patterning and growth of facial primordia. Genes Dev. 18, 937-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, R. and Gridley, T. (1997). Gene targeting: things go better with Cre. Curr. Biol. 7, R321-R323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney, A. M. and Rowitch, D. H. (2000). Sonic hedgehog promotes G(1) cyclin expression and sustained cell cycle progression in mammalian neuronal precursors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 9055-9067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Y., Kingsley, P. D., Cho, E. S. and Jiang, R. (2001). Osr2, a new mouse gene related to Drosophila odd-skipped, exhibits dynamic expression patterns during craniofacial, limb, and kidney development. Mech. Dev. 107, 175-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Y., Ovitt, C. E., Cho, E. S., Maltby, K. M., Wang, Q. and Jiang, R. (2004). Odd-skipped related 2 (Osr2) encodes a key intrinsic regulator of secondary palate growth and morphogenesis. Development 131, 3207-3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Y., Wang, Q., Ovitt, C. E. and Jiang, R. (2007). A unique mouse strain expressing Cre recombinase for tissue-specific analysis of gene function in palate and kidney development. Genesis 45, 618-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P. M., Dunn, M. P., McMahon, J. A., Logan, M., Martin, J. F., St-Jacques, B. and McMahon, A. P. (2001). Cholesterol modification of sonic hedgehog is required for long-range signaling activity and effective modulation of signaling by Ptc1. Cell 105, 599-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litingtung, Y., Lei, I., Westphal, H. and Chiang, C. (1998). Sonic hedgehog is essential to foregut development. Nat. Genet. 20, 58-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobjois, V., Benazeraf, B., Bertrand, N., Medevielle, F. and Pituello, F. (2004). Specific regulation of cyclins D1 and D2 by FGF and Shh signaling coordinates cell cycle progression, patterning, and differentiation during early steps of spinal cord development. Dev. Biol. 273, 195-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, F., Zhang, X. M., Karp, S., Yang, Y. and McMahon, A. P. (2001). Genetic manipulation of hedgehog signaling in the endochondral skeleton reveals a direct role in the regulation of chondrocyte proliferation. Development 128, 5099-5108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlappu, M., Enerback, S. and Carlsson, P. (2001a). Haploinsufficiency of the forkhead gene Foxf1, a target for sonic hedgehog signaling, causes lung and foregut malformations. Development 128, 2397-2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlappu, M., Ormestad, M., Enerback, S. and Carlsson, P. (2001b). The forkhead transcription factor Foxf1 is required for differentation of extraembryonic and lateral plate mesoderm. Development 128, 155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J. F., Bradley, A. and Olson, E. N. (1995). The paired-like homeobox gene Mhox is required for early events of skeletogenesis in multiple lineages. Genes Dev. 9, 1237-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, A. P., Ingham, P. W. and Tabin, C. J. (2003). Developmental roles and clinical significance of hedgehog signaling. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 53, 1-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mill, P., Mo, R., Hu, M. C., Dagnino, L., Rosenblum, N. D. and Hui, C. C. (2005). Shh controls epithelial proliferation via independent pathways that converge on N-Myc. Dev. Cell 9, 293-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo, R., Freer, A. M., Zinyk, D. L., Crackower, M. A., Michaud, J., Heng, H. H., Chik, K. W., Shi, X. M., Tsui, L. C., Chen, S. H. et al. (1997). Specific and redundant functions of Gli2 and Gli3 zinc finger genes in skeletal patterning and development. Development 124, 113-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohuchi, H., Nakagawa, T., Yamamoto, A., Araga, A., Ohata, T., Ishimaru, Y., Yoshioka, H., Kuwana, T., Nohno, T., Yamasaki, M. et al. (1997). The mesenchymal factor, FGF10, initiates and maintains the outgrowth of the chick limb bud through interaction with FGF8, an apical ectodermal factor. Development 124, 2235-2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, R., Spencer-Dene, B., Connor, E. C., Gritli-Linde, A., McMahon, A. P., Dickson, C., Thesleff, I. and Rice, D. P. (2004). Disruption of Fgf10/Fgfr2b-coordinated epithelial-mesenchymal interactions causes cleft palate. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1692-1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, R., Connor, E. and Rice, D. P. C. (2006). Expression patterns of Hedgehog signaling pathway members during mouse palate development. Gene Expr. Patterns 6, 206-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler, E. and Muenke, M. (2003). How a Hedgehog might see holoprosencephaly. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, R15-R25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, B. (1998). Inducible gene targeting in mice using the Cre/lox system. Methods 14, 381-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, P. (1999). Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet. 21, 70-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Jacques, B., Dassule, H. R., Karavanova, I., Botchkarev, V. A., Li, J., Danielian, P. S., McMahon, J. A., Lewis, P. M., Paus, R. and McMahon, A. P. (1998). Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr. Biol. 8, 1058-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao, H., Shimizu, M., Kusumoto, R., Ono, K., Noji, S. and Ohuchi, H. (2005). A dual role of Fgf10 in proliferation and coordinated migration of epithelial leading edge cells during mouse eyelid development. Development 132, 3217-3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, M. S. and Koch, W. E. (1977). In vitro development of palatal tissues from embryonic mice: II. Tissue isolation and recombination studies. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 38, 37-48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri Sani, F., Hallberg, K., Harfe, B. D., McMahon, A. P., Linde, A. and Gritli-Linde, A. (2005). Fate-mapping of the epithelial seam during palatal fusion rules out epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Dev. Biol. 285, 490-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T., Tamakoshi, T., Uezato, T., Shu, F., Kanzaki-Kato, N., Fu, Y., Koseki, H., Yoshida, N., Sugiyama, T. and Miura, N. (2003). Forkhead transcription factor Foxf2 (LUN)-deficient mice exhibit abnormal development of secondary palate. Dev. Biol. 259, 83-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, I. C., Hagge-Greenberg, A. and O'Brien, T. P. (2007). A dosage-dependent role for Spry2 in growth and patterning during palate development. Mech. Dev. 124, 746-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J. W., Kita, Y., Frank, D. J., Majewski, R. R., Konicek, B. A., Nobrega, M. A., Jacob, H., Walterhouse, D. and Iannaccone, P. (2002). Gene expression profiling leads to identification of GLI1-binding elements in target genes and a role for multiple downstream pathways in GLI1-induced cell transformation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5548-5555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L., Alappat, S., Song, S., Yan, Y., Zhang, M., Zhang, X., Jiang, G., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Z. and Chen, Y. P. (2005). Shox2-deficient mice exhibit a rare type of incomplete clefting of the secondary palate. Development 132, 4393-4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. M., Ramalho-Santos, M. and McMahon, A. P. (2001). Smoothened mutants reveal redundant roles for Shh and Ihh signaling including regulation of L/R symmetry by the mouse node. Cell 105, 781-792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. D., Zhao, X., Hu, Y., St Amand, T. R., Ramamurthy, R., Qiu, M. S. and Chen, Y. P. (1999). Msx1 is required for the induction of Patched by Sonic hedgehog in the mammalian tooth germ. Dev. Dyn. 215, 45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., Song, Y., Zhao, X., Zhang, X., Fermin, C. and Chen, Y. (2002). Rescue of cleft palate in Msx1-deficient mice by transgenic Bmp4 reveals a network of BMP and Shh signaling in the regulation of mammalian palatogenesis. Development 129, 4135-4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.