Abstract

Purpose: To determine whether a Bayesian network trained on a large database of patient demographic risk factors and radiologist-observed findings from consecutive clinical mammography examinations can exceed radiologist performance in the classification of mammographic findings as benign or malignant.

Materials and Methods: The institutional review board exempted this HIPAA-compliant retrospective study from requiring informed consent. Structured reports from 48 744 consecutive pooled screening and diagnostic mammography examinations in 18 269 patients from April 5, 1999 to February 9, 2004 were collected. Mammographic findings were matched with a state cancer registry, which served as the reference standard. By using 10-fold cross validation, the Bayesian network was tested and trained to estimate breast cancer risk by using demographic risk factors (age, family and personal history of breast cancer, and use of hormone replacement therapy) and mammographic findings recorded in the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System lexicon. The performance of radiologists compared with the Bayesian network was evaluated by using area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity.

Results: The Bayesian network significantly exceeded the performance of interpreting radiologists in terms of AUC (0.960 vs 0.939, P = .002), sensitivity (90.0% vs 85.3%, P < .001), and specificity (93.0% vs 88.1%, P < .001).

Conclusion: On the basis of prospectively collected variables, the evaluated Bayesian network can predict the probability of breast cancer and exceed interpreting radiologist performance. Bayesian networks may help radiologists improve mammographic interpretation.

© RSNA, 2009

The millions of mammographic examinations performed yearly in the United States (1) present interpretive and decision-making challenges that will result in substantial performance variability among radiologists and, therefore, suboptimal sensitivity and specificity (2). Practice differences between the United States and the United Kingdom suggest that high abnormal interpretation and biopsy rates may not translate into superior cancer detection (3). Such variability of practice presents an opportunity to develop decision support tools to aid radiologists in improving performance.

Errors can occur at several points in the pursuit of early breast cancer diagnosis. Findings must be detected on the mammogram, characterized in terms of relevant and predictive features, classified into disease categories, and, finally, applied to the patient so that appropriate treatment can be instituted. Errors are frequently made when estimating breast cancer risk before and after a mammographic examination because physicians must make complex judgments involving multiple variables (4). Although clinical information increases the accuracy of diagnostic tests (5–7) and providing patient-specific probability estimates can help less-experienced physicians improve to the level of experts (8), probability estimation is among the most error-prone components of clinical judgment (9,10).

Bayesian networks identify variables that influence the probability of an outcome of interest (like breast cancer) and apply the sequential Bayes formula for each variable to aid in risk prediction. We developed a Bayesian network to calculate the risk of malignancy on the basis of demographic risk factors (age, cancer history, and use of hormone replacement therapy) collected by the technologist and imaging features catalogued by the radiologist using the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) lexicon.

Our work builds on computer-assisted detection experience by addressing challenges identified in recent literature. Although results of evaluation of computer-assisted detection performance on the basis of nonconsecutive samples (11–16) and carefully controlled prospective assessment in clinical practice (17–21) have been promising, retrospective evaluation of actual clinical performance has demonstrated disappointing results (22,23). In fact, it has been suggested that the suboptimal performance indicates that computer-assisted detection may have unanticipated negative effects on radiologist decision making, perhaps by deferring recall when marks are not present (22,23). Several groups have improved classification of mammographic abnormalities (computer-assisted diagnosis) with computer-extracted imaging features (24–26) or with radiologist-observed features (27–31) in selected biopsy cases. We aim to extend this research by developing a Bayesian network that uses radiologist-observed features found in the American College of Radiology National Mammography Database (NMD) format (32,33). Our purpose is to determine whether a Bayesian network trained on a large database of patient demographic risk factors and radiologist-observed findings from consecutive clinical mammographic examinations can exceed radiologist performance in the classification of mammographic findings as benign or malignant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The institutional review board of the Froedtert and Medical College of Wisconsin exempted this Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant retrospective study from requiring informed consent.

The Model

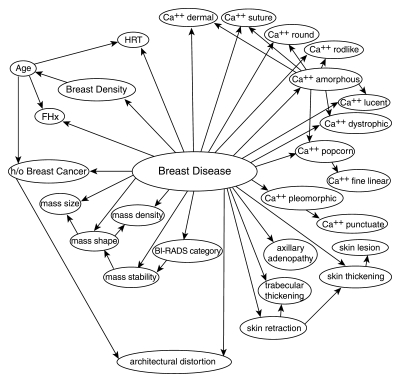

In general, a Bayesian network represents variables as “nodes,” which are data structures that contain an enumeration of possible values (“states”) and store probabilities associated with each state (Fig 1). For instance, the “root” node, entitled “breast disease,” has two states that represent the outcome of interest—benign or malignant—and stores the prior probability of these states (the prevalence of malignancy). The remaining nodes in the network represent demographic risk factors, BI-RADS descriptors, and the ultimate BI-RADS category (Table 1). Directed arcs in the Bayesian network encode dependence relationships among variables.

Figure 1:

Structure of the trained Bayesian network. Labeled circles represent nodes, and arrows (arcs) represent dependence relationships. Ca++ = calcifications, FHx = family history of breast cancer, h/o = history of, HRT = hormone replacement therapy.

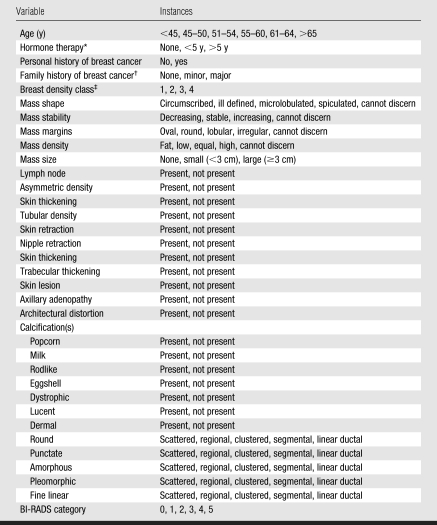

Table 1.

Variables from the NMD Used in the Bayesian Network

Note.—Cannot discern = missing data when the overall finding is present (eg, mass margin descriptor = “cannot discern” when mass size has been entered).

Estrogen based.

Minor = non–first-degree family member(s) with a diagnosis of breast cancer, major = one or more first-degree family members with a diagnosis of breast cancer.

Class 1 = predominantly fatty, class 2 = scattered fibroglandular densities, class 3 = heterogeneously dense tissue, class 4 = extremely dense tissue.

There are two approaches to building a Bayesian network: (a) Use preexisting knowledge about the probabilistic relationships among variables or (b) learn the probabilities and/or the structure from large existing data sets. In the past, investigators have typically used the former approach (30,31,34,35). In our study, we employed the latter approach (29) and trained the Bayesian network on existing clinical mammography findings. Our training process entailed determining the probabilities within each node, as well as discovering which arcs connected these nodes to capture dependence relationships. Once trained, the Bayesian network calculated a posttest probability of malignancy for each mammographic finding by using the structure and probabilities gleaned from the data.

The Bayesian network was trained by using an algorithm called tree augmented naive Bayes (36). The tree augmented naive Bayes algorithm produces the maximum likelihood structure given the constraint that each node can have at most one dependent node in addition to the root node. To train and test the Bayesian network model, we used a standard machine learning technique called 10-fold cross validation (Appendix E1, http://radiology.rsnajnls.org/cgi/content/full/2513081346/DC1). We observed the time required for Bayesian network inference as we estimated probabilities for each finding in order to consider the possible clinical implications of model use.

Study Design

We collected data for all screening and diagnostic mammography findings observed at the Froedtert and Medical College of Wisconsin Breast Care Center between April 5, 1999 and February 9, 2004. This clinical practice did not separate screening and diagnostic examinations during the time of our study, which prevents separate analysis of screening and diagnostic examinations. Therefore, we analyzed practice performance parameters for diagnostic and screening studies in aggregate (37).

The database held 48 744 mammographic examinations performed in 18 269 patients. All mammographic findings were described and recorded by using BI-RADS by the interpreting radiologist at the time of mammographic interpretation by using the structured reporting software (Mammography Information System, versions 3.4.99–4.1.22; PenRad, Minnetonka, Minn) routinely used in this practice.

There was a total of eight radiologists (including K.A.S.)—four of whom were general radiologists with some background in mammography, two of whom were fellowship trained, and two of whom had lengthy experience in breast imaging. Radiologist experience in mammographic interpretation ranged between 1 and 35 years (by the end of the study period). All radiologists were Mammography Quality Standards Act of 1992 certified. We obtained information regarding the reading radiologist by merging the PenRad data with the radiology information system (RIS) at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Five hundred four findings could not be assigned to a radiologist during our PenRad-RIS matching procedure. We elected to include unassigned findings in our analysis to maintain the consecutive nature of our data set.

We included all mammographic examinations, whether results were positive or negative. A negative mammogram was recorded as a single record with demographic data and BI-RADS assessment category populated but with finding descriptors left blank (because no finding was present). The term “finding” will be used throughout to denote the single record for normal mammograms or each record denoting an abnormality on a mammogram. The term “mammographic examination” will be used when we are referring to the entire mammographic study, including all views. The PenRad system records patient demographic risk factors, mammographic findings, and pathologic findings from biopsy in a structured format (ie, point-and-click entry of information populates the clinical report and the database simultaneously). The radiologist can also add details to the report by typing in free text, but these details are not captured in the database. We consolidated our database in the NMD format (32,38). Although the NMD format contains more than 100 variables, we included only those that were routinely collected in the practice and that were predictive of breast cancer (Table 1).

Classification accuracy was analyzed at the level of findings. Because image-based breast cancer classification (ultimately resulting in a biopsy recommendation) occurs primarily at the finding level, we believe this level of analysis is necessary to improve performance. However, the conventional analysis of mammographic data is at the level of the mammographic examination (where findings from a single study are combined). Because prior literature uses analysis at the mammogram level, we also did so for comparison (synthesizing the findings to the mammogram level by using the BI-RADS category of the most suspicious finding—where category 5 > 4 > 0 > 3 > 2 > 1—as in routine clinical practice). Specifically, we calculated the cancer detection rate, the early stage cancer detection rate, and the abnormal interpretation rate for all mammograms in our data set.

We matched the mammographic data with state cancer registry data as the reference standard. The Wisconsin Cancer Reporting System (WCRS), the state's population-based registry for cancer incidence data, has been collecting information from hospitals, clinics, and physicians since 1978. This registry collaborates with several other state and federal agencies to collect the standardized North American Association of Central Cancer Registries data elements, including demographic information, tumor characteristics, and treatment and mortality (39). Details of the data elements provided by the WCRS and our matching procedures are included in Appendix E2 (http://radiology.rsnajnls.org/cgi/content/full/2513081346/DC1). Because we were matching mammographic findings with cancers, the fact that the registry collects “subsite” (cancer location) information was extremely important (Appendix E2 and Table E1, http://radiology.rsnajnls.org/cgi/content/full/2513081346/DC1). The cancer registry achieves high rates of collection accuracy because it is supported by state law, which mandates reporting of all cancers by hospitals and physicians. The WCRS checks the accuracy of incoming cancer data by using nationally approved protocols, and any inconsistencies or errors are resolved with the reporting facility (39). We considered a registry report of ductal carcinoma in situ or any invasive carcinoma as positive. All other findings shown to be benign with biopsy or without a registry match within 365 days after the mammogram were considered negative.

Statistical Analysis

Using BI-RADS categories as ordinal response variables to reflect the increasing likelihood of breast cancer (where BI-RADS category 1 < 2 < 3 < 0 < 4 < 5) (40), we generated receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for all radiologists individually and in aggregate. Using the probabilities generated for all findings by means of 10-fold cross validation, we constructed ROC curves for the Bayesian network by calculating sensitivity and specificity using each of the possible predicted probabilities of malignancy as the threshold value for predicting malignancy. We calculated and compared areas under the ROC curves (AUCs) and generated confidence intervals by using the DeLong method (41).

We calculated baseline sensitivity and specificity of the radiologists (in aggregate and individually) at the operating point of BI-RADS category 3 (with BI-RADS category 3 considered negative) because above this level, biopsy would be recommended. We then calculated the Bayesian network sensitivity at the baseline specificity of the radiologists and the Bayesian network specificity at the baseline sensitivity of the radiologist. We compared sensitivity and specificity (between radiologists and the Bayesian network) by using the McNemar test to account for the lack of independence between the sensitivity and specificity ratios. The McNemar test is not defined when the ratios are equal, nor when one of the ratios is 0 or 1. We generated confidence intervals for sensitivity and specificity by using the Wilson method (42). We consistently considered BI-RADS categories 0, 4, and 5 as positive and BI-RADS categories 1, 2, and 3 as negative.

To understand whether the Bayesian network affected biopsy rates, recall, or follow-up recommendations, we evaluated multiple probability thresholds (0.05%, 0.1%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0%, 3.0%, 4.0%, and 5.0%) within BI-RADS categories. In addition, we selectively reviewed the collected variables of breast cancers missed at multiple threshold levels to try to explain why risk prediction failed in these cases.

RESULTS

After matching to the cancer registry, there were 62 219 findings (510 malignant, 61 709 benign) in 48 744 women and 398 men for analysis. The mean age of the female patient population was 56.5 years ± 12.7 (standard deviation) (range, 17.7–99.1 years), while the mean age of the male patient population was 58.5 years ± 15.7 (range, 18.6–88.5 years). Fourteen percent of findings were in predominantly fatty tissue, 41% were in scattered fibroglandular tissue, 36% were in heterogeneously dense tissue, and 8% were in extremely dense tissue. The cancers included 246 masses, 121 microcalcifications, 27 asymmetries, 18 architectural distortions, 86 combinations of findings, and 12 findings categorized as “other.”

Using analysis on the mammography level, the radiologists detected 8.9 cancers per 1000 mammograms (432 cancers per 48 744 mammograms). The abnormal interpretation rate (considering BI-RADS categories 0, 4, and 5 as abnormal) was 18.5% (9037 of 48 744 mammograms). Of all 432 detected cancers, 390 had staging information from the cancer registry and 42 did not. Of the cases with stage available, 71.0% (277 of 390) were early stage (stage 0 or 1), and 26.7% (104 of 390) had lymph node metastasis.

The tree augmented naive Bayes algorithm identified many predictive variables that were dependent on one another. Each dependence relationship in the Bayesian network is demonstrated by a directed arc (Fig 1).

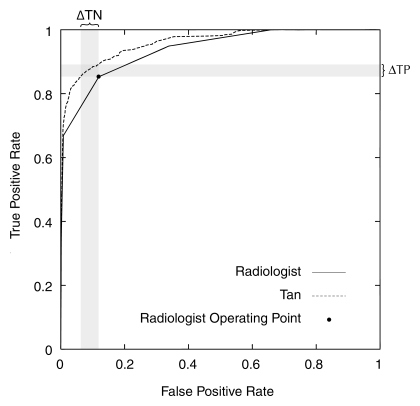

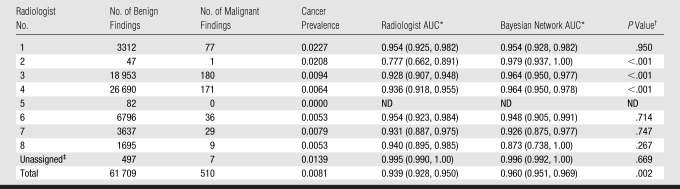

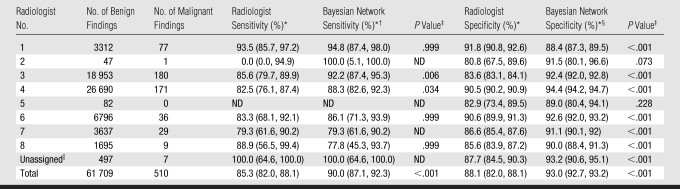

At the finding level, the Bayesian network provided a significant improvement in AUC compared with the interpreting radiologists (0.960 vs 0.939, P = .002). The ROC curve for the Bayesian network surpassed that of the radiologists at all threshold levels (Fig 2). The Bayesian network demonstrated superior AUC performance as compared with three radiologists, including the two readers with the highest volumes (Table 2). Hence, the Bayesian network significantly improved on radiologists' specificity (93.0% vs 88.1%, P < .001) at a sensitivity of 85.3% and radiologists' sensitivity (90.0% vs 85.3%, P < .001) at a specificity of 88.1% (Table 3). The Bayesian network was also superior to the two high-volume readers in terms of sensitivity and specificity. The Bayesian network exceeded several low-volume readers in specificity. Only one low-volume radiologist (radiologist 1 in Table 3) exceeded the Bayesian network in specificity. The time required for Bayesian network inference per finding was consistently less than 1 second.

Figure 2:

ROC curves constructed from the BI-RADS categories of the radiologists and the predicted probabilities of the Bayesian network. The radiologists' operating point is considered the BI-RADS category 3 point, corresponding to a threshold above which biopsy would be recommended. ΔTN = change in true-negatives (which results in improved specificity), ΔTP = change in true-positives (which results in improved sensitivity), Tan = tree augmented naive Bayes algorithm.

Table 2.

Comparison of Radiologist and Bayesian Network AUCs

Note.—ND = not defined.

Data in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

Calculated with DeLong test of difference between two dependent AUCs.

Unassigned mammographic studies resulting from inability to match studies with radiologists when merging mammography reporting system and institutional radiology information system.

Table 3.

Comparison of Radiologist and Bayesian Network Sensitivity and Specificity

Note.—ND = not defined.

Data in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

At a radiologist specificity of 88.1%.

Calculated with McNemar test.

At a radiologist sensitivity of 85.3%.

Unassigned mammographic studies resulting from inability to match studies with radiologists when merging mammography reporting system and institutional radiology information system.

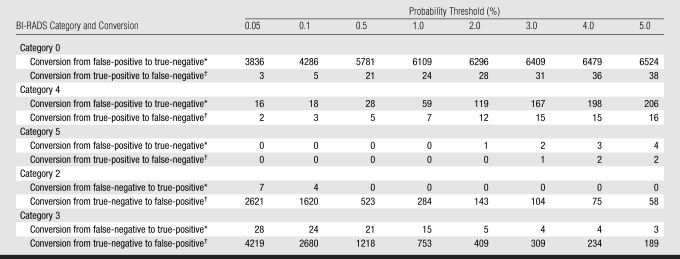

By dividing findings into BI-RADS categories (with multiple threshold levels at which to determine positive or negative), we demonstrated a trade-off between cases correctly classified versus erroneously classified by the Bayesian network at each threshold level (Table 4). For positive studies (BI-RADS categories 0, 4, and 5), conversions from false-positive to true-negative dominated other conversions, particularly at higher threshold levels, which explains how the Bayesian network improved overall specificity. For negative findings (BI-RADS categories 2 and 3), conversions from false-negatives to true-positives were most notable at lower threshold levels, which explains how the Bayesian network improved sensitivity. Overall, a reduction of misclassification in BI-RADS category 0 assessments dominated the results when all threshold levels were considered. At review of the reports that represented consistently missed breast cancers, predictive BI-RADS terms in the text reports were not contained in the structured reports used by the Bayesian network.

Table 4.

Performance within BI-RADS Categories as Function of Probability Threshold

Note.—Data are numbers of findings.

Findings for which the Bayesian network corrected an erroneous assessment by the radiologist.

Findings for which the Bayesian network erroneously converted a correct assessment by the radiologist.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate that our Bayesian network can use a database of prospectively collected findings at mammography to calculate an accurate risk of malignancy and improve on radiologist performance measures in the classification of benign and malignant breast disease. Our results show significantly superior Bayesian network performance in terms of AUC, sensitivity, and specificity compared with all radiologists in aggregate. When individual radiologist performance was compared with the Bayesian network for the same findings, the Bayesian network showed superior performance in AUC, sensitivity, and specificity versus the two highest-volume readers and superior specificity versus all but two radiologists. Only one radiologist significantly outperformed the Bayesian network in specificity (but not in sensitivity or AUC).

The radiologist and the Bayesian network each provides a valuable component to the final risk prediction that contributes to improved performance. Specifically, the radiologist provides observations and assessments that the Bayesian network combines in a mathematically rigorous manner with “knowledge” of similar past findings to generate accurate predictions. Ideally, the radiologist and the Bayesian network would be able to work together, in real time, to catalogue the features that are most important for a given finding and optimize the predictions in the appropriate clinical context. Our retrospective analysis is a somewhat artificial judge of the potential of Bayesian risk prediction but should be viewed as a first step. The comparison between the Bayesian network and the radiologist is also imperfect because the radiologist is performing a highly complex task—beyond simply classifying findings as benign or malignant—while the Bayesian network has been trained specifically for that task alone. Therefore, our comparison certainly does not imply that the Bayesian network could replace the radiologist but may indicate that the Bayesian network can calculate risk across many variables, incorporate complex dependencies among variables, and aid the radiologists' interpretations. Although the Bayesian network demonstrated many expected dependencies (eg, between descriptors in similar descriptor categories: between microcalcification types, mass types, skin findings, and demographic risk factors), it also revealed some unexpected dependencies (eg, the dependence of BI-RADS category and mass stability). The inability to account for these dependencies without help from a computer may account for some radiologist errors and performance variability.

The Bayesian network appears to be most effective in decreasing the need for recall (substantially reducing BI-RADS category 0 interpretations), which may address problems encountered in the clinical testing of computer-assisted detection (22,23). The Bayesian network classified thousands of false-positive BI-RADS category 0 assessments correctly as negative (Table 4), which may have the potential to decrease patient anxiety and the need for additional testing (whether this may be during the screening or the diagnostic step). In fact, a probability assessment at the time of a BI-RADS category 0 evaluation may facilitate communication between the patient and the physician, as well as assist in the determination of appropriate treatment.

However, the threshold that enables accurate classification of BI-RADS category 0 findings may be accompanied by trade-offs. A small number of BI-RADS category 0, 4, or 5 cancers may be missed (true-positives converted to false-negatives), and accurately assessed BI-RADS category 2 and 3 findings may raise suspicion (true-negatives converted to false-positives). However, the missed cancers shown in Table 4 often did not have the appropriate descriptors recorded in the database. All three BI-RADS category 0 breast cancers missed at the 0.05% threshold had erroneously recorded descriptors. For example, in one of these cases, a new oval mass with an obscured margin was recorded in the text report, but the structured data from PenRad recorded a lymph node. Our results depend entirely on the quality of the structured data entered by the radiologist in clinical practice, which is certainly not perfect. In fact, 3285 records documented BI-RADS categories that indicated findings (BI-RADS category 0, 3, 4, or 5) but contained no specific finding descriptors (Appendix E2, http://radiology.rsnajnls.org/cgi/content/full/2513081346/DC1). Apparently, the radiologist typed the results rather than entering structured data. Clearly, improvements in structured reporting, including consistency checks between recorded predictive variables and text reports, will be necessary before the data can be reliably used for decision support. This problem would also likely be addressed if the radiologist were interacting with the system in real time. Because Bayesian network inference takes less than 1 second, real-time interaction between the radiologist and the Bayesian network is entirely feasible. However, Bayesian network integration with the mammography reporting system, which is not currently available, would be important for optimal workflow.

The impact of reversals in correctly assessed BI-RADS category 2 and 3 findings is difficult to evaluate without knowing the predicted probability and the clinical context. It is possible that the probability of malignancy in these cases was not much higher than the threshold and would not have generated additional imaging or biopsy. A future clinical trial of Bayesian decision support is the only way that we will be able to tease out how performance differences identified in our retrospective analysis would translate to the more ideal scenario of risk prediction at the point of care.

The Bayesian network works very differently from conventional computer-assisted detection algorithms (11–21) that provide a mark on the image (adding yet another variable to the radiologist's long list of breast cancer predictors). The Bayesian network provides a posttest probability that consolidates all the predictive variables in the NMD (demographic variables, mammographic descriptors, and BI-RADS assessment categories) into a probability of malignancy. It is possible that the predictive ability of these variables may be redundant and of differential value. However, the literature clearly shows that descriptors, as well as BI-RADS categories, can be variable and sometimes inaccurate (43–45); therefore, inclusion of all variables will likely ameliorate such errors. We did not attempt to determine the most predictive variables (demographic variables, descriptors, or ultimate BI-RADS categories), but plan this for future work.

There are also substantial differences between our Bayesian network and other computer-assisted diagnosis systems that use suspicious cases selected from biopsy databases to train their systems (24,25,27,30,31,34,46,47). Our Bayesian network, in contrast, was trained on consecutively collected mammographic findings, perhaps allowing it to more accurately estimate posttest probabilities and better balance improvements in sensitivity and specificity with more realistic estimates of breast cancer prevalence. The consecutive nature of our data set helped ensure that we did not exclude select groups from our study and may indicate future generalizability to similar mammography practices. Further research is needed to validate this theory.

Our Bayesian network also differs from general risk prediction models (48–51) like the Gail model, which predicts the probability that a woman will develop breast cancer sometime in the future. The Bayesian network estimates breast cancer risk at a particular point in time. A woman at high risk for breast cancer can have a finding with a low probability of malignancy, and a woman at low risk can have a finding with a high probability of malignancy, depending on her mammographic results (52). Single-time-point risk information is more appropriate for driving management decisions such as recall or biopsy.

Our study reinforces the belief that the mammographic features catalogued in BI-RADS can help classify breast findings (32,53,54) but raises concerns about interobserver variability (43,55). Despite performance variability among the radiologists in our study, the consistently superior performance of the Bayesian network suggests that such variability is not an insurmountable problem. Although the important question of how much interobserver variability affects Bayesian network performance is outside the scope of this article, we have done preliminary work demonstrating that training and testing the Bayesian network with individual radiologists does not significantly change the results (56). Ultimately, proof of the generalizability of our Bayesian network to additional radiologists or practices will require further research.

The most fundamental limitation to our study was that screening and diagnostic mammography were not analyzed separately. This issue is not uncommon and has been previously reported in the literature (37). In general, the mixed screening and diagnostic findings affected the prevalence of cancer and the skew (many more negative than positive cases), which in turn likely affected our results to some degree. For example, the prevalence in our pooled population was higher than that in a pure screening group and lower than that in a pure diagnostic group. Our pooled population was less skewed than a pure screening group and more skewed than a pure diagnostic population. These differences likely hinder the predictive ability of our Bayesian network by adding to the variability of the data without providing a node (ie, screening or diagnostic) in the network to explain that variability. Therefore, our performance estimates may be pessimistic. Although the performance achieved by the Bayesian network in a mixed data set is encouraging, we plan future studies on screening and diagnostic mammography separately to see if performance differs in either of these types of examinations in isolation. Our comparison of ROC curves between the radiologists and the Bayesian network was also suboptimal, because while the radiologists summarized their assessments in BI-RADS categories, the Bayesian network output was measured in probability. Although a similar analysis has been presented in the literature (50), it is not a perfectly equal comparison. These concerns are ameliorated somewhat in our work by the fact that the performance of the Bayesian network was superior to that of the radiologist at all threshold levels. Further work in equalizing ROC comparisons when the output scalars are distinct would be helpful. Finally, the fact that a small proportion of findings could not be matched to a reading radiologist represented a minor limitation. We made the decision to include these findings to preserve the consecutive nature of our population.

In conclusion, our study results demonstrate that a Bayesian network can accurately estimate the probability of breast cancer for findings identified at mammography, identify dependencies among predictive variables, and perform better than interpreting radiologists alone. The Bayesian network is not intended to replace the radiologist but rather to capitalize on the radiologist's skill in characterizing findings while aiding in the mathematic integration of predictive variables into an accurate risk assessment. In the future, probabilistic computer models like this Bayesian network may substantially aid physicians attempting to diagnose breast cancer in a timely and accurate manner.

ADVANCES IN KNOWLEDGE

A Bayesian network computer model that uses Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System descriptors can accurately predict the probability of malignancy of a finding at mammography.

A Bayesian network achieved a superior area under the receiver operating characteristic curve compared with the interpreting radiologist for consecutive mammographic findings.

IMPLICATION FOR PATIENT CARE

Bayesian networks may help radiologists improve mammographic interpretation.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

AUC = area under the ROC curve

BI-RADS = Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System

NMD = National Mammography Database

ROC = receiver operating characteristic

Author contributions: Guarantors of integrity of entire study, E.S.B., C.D.P.; study concepts/study design or data acquisition or data analysis/interpretation, all authors; manuscript drafting or manuscript revision for important intellectual content, all authors; manuscript final version approval, all authors; literature research, E.S.B., J.C., O.A., C.E.K., C.D.P.; clinical studies, E.S.B.; experimental studies, E.S.B., J.D., C.E.K., C.D.P.; statistical analysis, E.S.B., J.D., J.C., M.J.L., B.L., C.D.P.; and manuscript editing, all authors

Authors stated no financial relationship to disclose.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants K07-CA114181, R01-CA127379, and R21-CA129393).

References

- 1.Day JC. Population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1995 to 2050, U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, P25-1130. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1996.

- 2.Sickles EA, Wolverton DE, Dee KE. Performance parameters for screening and diagnostic mammography: specialist and general radiologists. Radiology 2002;224:861–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith-Bindman R, Chu PW, Miglioretti DL, et al. Comparison of screening mammography in the United States and the United Kingdom. JAMA 2003;290:2129–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahneman D, Slovic P, Tversky A. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- 5.Houssami N, Irwig L, Simpson JM, McKessar M, Blome S, Noakes J. The influence of clinical information on the accuracy of diagnostic mammography. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2004;85:223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwig L, Macaskill P, Walter SD, Houssami N. New methods give better estimates of changes in diagnostic accuracy when prior information is provided. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loy CT, Irwig L. Accuracy of diagnostic tests read with and without clinical information: a systematic review. JAMA 2004;292:1602–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter BL, Butler CD, Rogers JC, Holloway RL. Evaluation of physician decision making with the use of prior probabilities and a decision-analysis model. Arch Fam Med 1993;2:529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong A, Barnett GO, Mosteller F, Youtz C. How medical professionals evaluate expressions of probability. N Engl J Med 1986;315:740–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyman GH, Balducci L. Overestimation of test effects in clinical judgment. J Cancer Educ 1993;8:297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker JA, Kornguth PJ, Lo JY, Floyd CE Jr. Artificial neural network: improving the quality of breast biopsy recommendations. Radiology 1996;198:131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker JA, Kornguth PJ, Lo JY, Williford ME, Floyd CE Jr. Breast cancer: prediction with artificial neural network based on BI-RADS standardized lexicon. Radiology 1995;196:817–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker JA, Rosen EL, Lo JY, Gimenez EI, Walsh R, Soo MS. Computer-aided detection (CAD) in screening mammography: sensitivity of commercial CAD systems for detecting architectural distortion. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:1083–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadjiiski L, Chan HP, Sahiner B, et al. Improvement in radiologists' characterization of malignant and benign breast masses on serial mammograms with computer-aided diagnosis: an ROC study. Radiology 2004;233:255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malich A, Marx C, Facius M, Boehm T, Fleck M, Kaiser WA. Tumour detection rate of a new commercially available computer-aided detection system. Eur Radiol 2001;11:2454–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warren Burhenne LJ, Wood SA, D'Orsi CJ, et al. Potential contribution of computer-aided detection to the sensitivity of screening mammography. Radiology 2000;215:554–562. [Published correction appears in Radiology 2000;216(1):306.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birdwell RL, Bandodkar P, Ikeda DM. Computer-aided detection with screening mammography in a university hospital setting. Radiology 2005;236:451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cupples TE, Cunningham JE, Reynolds JC. Impact of computer-aided detection in a regional screening mammography program. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;185:944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean JC, Ilvento CC. Improved cancer detection using computer-aided detection with diagnostic and screening mammography: prospective study of 104 cancers. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187:20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freer TW, Ulissey MJ. Screening mammography with computer-aided detection: prospective study of 12,860 patients in a community breast center. Radiology 2001;220:781–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morton MJ, Whaley DH, Brandt KR, Amrami KK. Screening mammograms: interpretation with computer-aided detection—prospective evaluation. Radiology 2006;239:375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fenton JJ, Taplin SH, Carney PA, et al. Influence of computer-aided detection on performance of screening mammography. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1399–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gur D, Wallace LP, Klym AH, et al. Trends in recall, biopsy, and positive biopsy rates for screening mammography in an academic practice. Radiology 2005;235:396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Y. Computer-aided diagnosis of breast cancer in mammography: evidence and potential. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2002;1:211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leichter I, Fields S, Nirel R, et al. Improved mammographic interpretation of masses using computer-aided diagnosis. Eur Radiol 2000;10:377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishikawa RM. Current status and future directions of computer-aided diagnosis in mammography. Comput Med Imaging Graph 2007;31:224–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilska-Wolak AO, Floyd CE Jr, Lo JY, Baker JA. Computer aid for decision to biopsy breast masses on mammography: validation on new cases. Acad Radiol 2005;12:671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo JY, Markey MK, Baker JA, Floyd CE Jr. Cross-institutional evaluation of BI-RADS predictive model for mammographic diagnosis of breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002;178:457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer EA, Lo JY, Markey MK. Bayesian networks of BI-RADS descriptors for breast lesion classification. In: Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference of the IEEE EMBS, San Francisco CA, USA, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Kahn CE Jr, Roberts LM, Wang K, Jenks D, Haddawy P. Preliminary investigation of a Bayesian network for mammographic diagnosis of breast cancer. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care 1995; 208–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Burnside ES, Rubin DL, Fine JP, Shachter RD, Sisney GA, Leung WK. Bayesian network to predict breast cancer risk of mammographic microcalcifications and reduce number of benign biopsy results: initial experience. Radiology 2006;240:666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American College of Radiology. Breast Imaging Reporting And Data System (BI-RADS). Reston, Va: American College of Radiology, 1998.

- 33.American College of Radiology. National mammography database. Reston, Va: American College of Radiology, 2001.

- 34.Burnside E, Rubin D, Shachter R. A Bayesian network for mammography. Proc AMIA Symp 2000; 106–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Burnside ES, Rubin DL, Shachter RD, Sohlich RE, Sickles EA. A probabilistic expert system that provides automated mammographic-histologic correlation: initial experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;182:481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman N, Geiger D, Goldszmidt M. Tree-augmented naïve Bayes or tree-augmented network. Mach Learn 1997;29:131–163.

- 37.Sohlich RE, Sickles EA, Burnside ES, Dee KE. Interpreting data from audits when screening and diagnostic mammography outcomes are combined. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002;178:681–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osuch JR, Anthony M, Bassett LW, et al. A proposal for a national mammography database: content, purpose, and value. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;164:1329–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foote M. Wisconsin Cancer Reporting System: a population-based registry. WMJ 1999;98:17–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barlow WE, Chi C, Carney PA, et al. Accuracy of screening mammography interpretation by characteristics of radiologists. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:1840–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agresti A, Coull B. Approximate is better than “exact” for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Am Stat 2000;52:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker JA, Kornguth PJ, Floyd CE Jr. Breast imaging reporting and data system standardized mammography lexicon: observer variability in lesion description. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;166:773–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lehman C, Holt S, Peacock S, White E, Urban N. Use of the American College of Radiology BI-RADS guidelines by community radiologists: concordance of assessments and recommendations assigned to screening mammograms. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002;179:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taplin SH, Ichikawa LE, Kerlikowske K, et al. Concordance of breast imaging reporting and data system assessments and management recommendations in screening mammography. Radiology 2002;222:529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buchbinder SS, Leichter IS, Lederman RB, et al. Computer-aided classification of BI-RADS category 3 breast lesions. Radiology 2004;230:820–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Floyd CE Jr, Lo JY, Tourassi GD. Case-based reasoning computer algorithm that uses mammographic findings for breast biopsy decisions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;175:1347–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Decarli A, Calza S, Masala G, Specchia C, Palli D, Gail MH. Gail model for prediction of absolute risk of invasive breast cancer: independent evaluation in the Florence-European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:1686–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bondy ML, Newman LA. Assessing breast cancer risk: evolution of the Gail model. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:1172–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barlow WE, White E, Ballard-Barbash R, et al. Prospective breast cancer risk prediction model for women undergoing screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:1204–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tice JA, Cummings SR, Smith-Bindman R, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Kerlikowske K. Using clinical factors and mammographic breast density to estimate breast cancer risk: development and validation of a new predictive model. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:337–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weaver DL, Vacek PM, Skelly JM, Geller BM. Predicting biopsy outcome after mammography: what is the likelihood the patient has invasive or in situ breast cancer? Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12:660–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liberman L, Abramson AF, Squires FB, Glassman JR, Morris EA, Dershaw DD. The breast imaging reporting and data system: positive predictive value of mammographic features and final assessment categories. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;171:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burnside ES, Ochsner JE, Fowler KJ, et al. Use of microcalcification descriptors in BI-RADS 4th edition to stratify risk of malignancy. Radiology 2007;242:388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berg WA, D'Orsi CJ, Jackson VP, et al. Does training in the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) improve biopsy recommendations or feature analysis agreement with experienced breast imagers at mammography? Radiology 2002;224:871–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kahn CE Jr, McCarthy KA, Burnside ES. Do computer-aided diagnosis systems in mammography need to be trained to individual observers? [abstr]. In: Radiological Society of North America Scientific Assembly and Annual Meeting Program. Oak Brook, Ill: Radiological Society of North America, 2005; 491.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.