Abstract

Toothbrush swallowing is a rare event. Because no cases of spontaneous passage have been reported, prompt removal is recommended to prevent the development of complications. Most swallowed toothbrushes have been found in the esophagus or the stomach of affected patients, and there has been no previously reported case of a toothbrush in the colon. Here, we report a case of a swallowed toothbrush found in the ascending colon that caused a fistula between the right colon and the liver, with a complicating small hepatic abscess. This patient was successfully managed using exploratory laparotomy. To our knowledge, this is the first documented case of a swallowed toothbrush found in the colon.

Keywords: Toothbrush, Colon, Laparotomy

INTRODUCTION

The ingestion of a foreign body is a frequent cause of gastrointestinal emergency. Most ingested foreign bodies pass through the gastrointestinal tract spontaneously without necessitating any treatment; however, about 20% require endoscopic or surgical removal1). Toothbrush swallowing is a rare event. Most swallowed toothbrushes have been found in the esophagus or the stomach of the affected patient, and there has been no previously reported case of a toothbrush in the colon. Here, we report a case of a swallowed toothbrush found in the ascending colon with a complicating small hepatic abscess, which was successfully managed with laparotomy. We also review the literature on injuries from ingested toothbrushes.

CASE REPORT

A 31-year-old man presented with a one-week history of intermittent right upper abdominal pain. The pain was dull in character and moderately severe in intensity. He felt nausea and rigors with the pain. He saw his local doctor when symptoms began, and was prescribed ranitidine and antacid for dyspepsia with no improvement. He had been treated for 13 years due to a diagnosis of schizophrenia. On examination, the patient was febrile at 38.1℃, his heart rate was 76 b.p.m., his blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, and he was not jaundiced or anemic. His abdomen was lax, but he had moderate right upper quadrant tenderness. Bowel sounds were normal.

His full blood examination showed mild leukocytosis (12.2 109/L) with neutrophilia. Liver function tests showed mildly elevated AST (51 IU/L) and ALT (78 IU/L) levels. Amylase and lipase levels were normal. The C-reactive protein level was high (141 mg/L). The coagulation profile was abnormal with a prothrombin time (international normalized ratio) of 1.4 and an activated partial thromboplastin time of 40 s. An electrocardiogram was unremarkable.

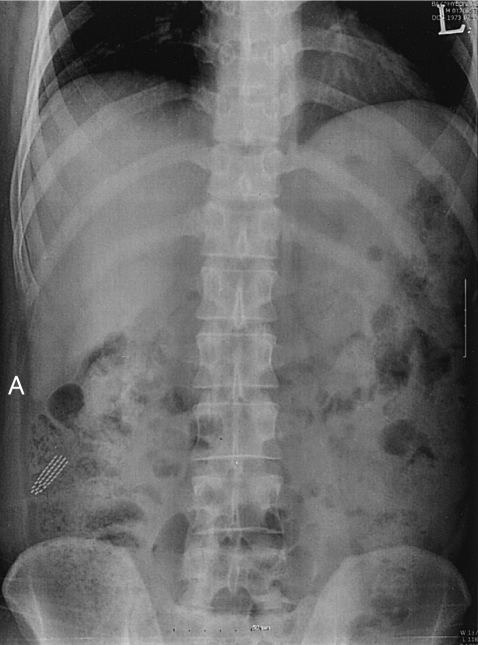

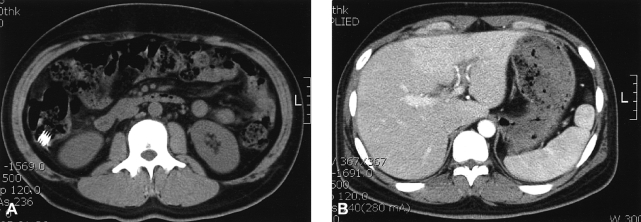

An abdominal radiograph showed parallel rows of short metallic radiodensities in the right mid-abdomen (Figure 1). On CT images, a metallic foreign body was observed in the right colon and a thrombosis of the left portal vein was found to be associated with perfusion changes in the left hepatic lobe, suggesting a chronic intra-abdominal inflammation (Figure 2). Colonoscopic examination revealed a toothbrush penetrating the wall of the hepatic flexure with the head pointing toward the ascending colon (Figure 3). We attempted to remove the toothbrush after grasping it with a snare; this attempt failed due to limited space in the hepatic flexure and risk of trauma to extraluminal organs or vessels. The patient was subsequently taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. During laparotomy, an abscess cavity involving the inferior aspect of the liver was discovered. The toothbrush was found to have caused a fistula between the hepatic flexure of the colon and the liver with a complicating small hepatic abscess. The toothbrush at 19 cm in length was removed, the perforation in the colon was resected in a small wedge, and anastomosis was performed. The peritoneal cavity was irrigated with normal saline, and a 10-Fr drain tube was placed in the abscess cavity site. Postoperatively, the patient had a favorable outcome. Upon further questioning, the patient reported ingesting a toothbrush approximately one year earlier. At that time, the patient had visited a local clinic where they recommended surgical removal. However, he had adamantly refused surgery.

Figure 1.

Abdominal radiograph shows metallic radiodensities in the right mid-abdomen.

Figure 2.

A CT scan of the abdomen demonstrates metallic densities located in the right colon (A) and thrombosis of the left portal vein (B).

Figure 3.

Colonoscopic image at the hepatic flexure shows a toothbrush penetrating the wall of the hepatic flexure (A) with the head pointing toward the ascending colon (B).

DISCUSSION

The toothbrush is a rather unusual foreign body to be found in the gastrointestinal tract. In a recent report, a MEDLINE search of the years 1988 to 2000 found 11 articles with approximately 40 cases of toothbrush ingestion2). Almost all of the patients were female, ranging from 15 to 23 years of age3, 4). Most of the patients had been diagnosed with psychiatric problems such as bulimia or anorexia nervosa. The characteristic radiographic image of a swallowed toothbrush shows parallel rows of short metallic radiodensities due to the metallic plates that hold the bristles in place4). The toothbrushes were easily identified in the esophagus and stomach of the patients by upper endoscopy. None of the toothbrushes passed spontaneously. In several cases, there were significant complications related to pressure necrosis, including gastritis, mucosal tears, and perforation3). Consequently, prompt removal is recommended to prevent the development of complications. In 1983, the first case of successful endoscopic toothbrush removal was reported5). Other cases have reported failure of endoscopic removal due to the size or shape of the toothbrush6, 7). In addition, cases of esophageal perforation during endoscopic toothbrush extraction8) and of laparoscopic-assisted toothbrush extraction via gastrostomy after an unsuccessful attempt at endoscopic removal7) have been reported. Consequently, endoscopic retrieval is the recommended treatment. However, surgical removal is often required due to the geometric qualities of the toothbrush.

All of the swallowed toothbrushes were found in the esophagus or the stomach of the affected patient, and there has been no previously reported case of a toothbrush in the colon. To our knowledge, this is the first documented case of a swallowed toothbrush found in the colon and persisting in the gastrointestinal tract for approximately one year. For a small foreign body penetrating the wall of the colon with no sign of peritoneal irritation, it may be possible to remove the foreign body and repair the wound endoscopically. In our case, we found the endoscopic approach unsuccessful due to the size of the toothbrush and the narrow space of the hepatic flexure. There was also a complicating abscess and a risk of trauma to extraluminal organs or vessels during endoscopic removal. Therefore, we proceeded with a prompt surgical approach. The case presented demonstrates a very unusual complication of toothbrush ingestion, unlike any that have been reported previously. Thus, a typical finding of an unusual foreign body in the colon, especially in patients with psychiatric problems, should make the attending physician consider the possibility of a swallowed toothbrush. Because no cases of spontaneous passage have been reported, prompt removal is recommended to minimize morbidity and to avoid prolonged hospitalization.

References

- 1.Ginsberg GG. Management of ingested foreign objects and food bolus impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:33–38. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faust J, Schreiner O. A swallowed toothbrush. Lancet. 2001;357:1012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirk AD, Bowers BA, Moylan JA, Meyers WC. Toothbrush swallowing. Arch Surg. 1988;123:382–384. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400270122020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riddlesberger MM, Jr, Cohen HL, Glick PL. The swallowed toothbrush: a radiographic clue of bulimia. Pediatr Radiol. 1991;21:262–264. doi: 10.1007/BF02018618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ertan A, Kedia SM, Agrawal NM, Akdamar K. Endoscopic removal of a toothbrush. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:144–145. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(83)72564-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilcox DT, Karamanoukian HL, Glick PL. Toothbrush ingestion by blumics may require laparotomy. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1596. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wishner JD, Rogers AM. Laparoscopic removal of a swallowed toothbrush. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:472–473. doi: 10.1007/s004649900393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selivanov V, Sheldon GF, Cello JP, Crass RA. Management of foreign ingestion. Ann Surg. 1984;199:187–191. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198402000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]