Abstract

Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP) is a poorly understood and rarely documented cause of small bowel obstruction. Although recurrent peritonitis has been reported as the main contributory factor leading to secondary SEP, the pathogenesis of primary (idiopathic) SEP is still uncertain.

A 40-year-old woman with a history of total abdominal hysterectomy due to gestational trophoblastic disease presented with progressive lower abdominal pain and abdominal distension. Ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced abdomen-pelvis computed tomography of the abdomen revealed encapsulation of the entire small bowel with a sclerotic capsule. At laparotomy, a fibrous thick capsule encasing small bowel loops was revealed. Extensive adhesiolysis and removal of the capsule from the bowel loops were performed. The patient recovered uneventfully; she was discharged without complications.

SEP is a rare cause of small bowel obstruction. We treated a case of abdominal cocoon with intestinal partial obstruction in a woman with a history of abdominal hysterectomy due to gestational trophoblastic disease. Surgical treatment was effective and the patient recovered without complication.

Keywords: Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis, Abdominal cocoon, Small bowel obstruction, Abdominal hysterectomy

INTRODUCTION

Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP), characterized by a thick and fibrotic membrane, is a rare cause of small bowel obstruction; its pathogenesis is poorly understood1, 2, 4). Idiopathic SEP, also known as abdominal cocoon, was first described in young girls by Foo et al.; it was thought to be caused by a low-grade peritonitis from retrograde menstruation3). However, subsequently there were sporadic reports in older patients of both genders4). Secondary SEP occurs most frequently in patients on chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis5, 6).

Here, we report a case of sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis with partial small bowel obstruction that developed 3 years after abdominal hysterectomy for gestational trophoblastic disease.

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old woman presented with a history of progressive lower abdominal pain, abdominal distension and frequent gas of 2 years duration. The patient had a history of abdominal hysterectomy for gestational trophoblastic disease 3 years prior to presentation. . The patient reported intermittent episodes of abdominal colicky pain and bloating after a meal two years post surgery. The symptoms were becoming more frequent and serious. There was no other significant medical history such as diabetes mellitus, liver disease or medication.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. The abdomen was distended but non-tender with increased bowel sounds in pitch and frequency. No palpable mass or organomegaly and no external hernias were present. Laboratory blood analyses including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were within normal limits. Plain abdominal X-ray showed marked small bowel dilatation and air collection with air-fluid levels centrally located (Figure 1). Ultrasonography of the abdomen revealed that the small bowel was surrounded by a membranous structure with a thickness from 3.5 mm to 6.1 mm (Figure 2). The patient was admitted to the general ward of our hospital with the impression of intestinal obstruction. Contrast-enhanced abdomen-pelvis computed tomography performed initially showed encapsulation of the entire small bowel with a sclerotic capsule, without a luminal obstructive lesion or ischemic change of the small bowel (Figure 3). There was also a small amount of ascites in the pelvic cavity and several slightly enlarged lymph nodes at the ileocolic area by CT scan. Endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract did not demonstrate any abnormalities except a short segment of Barrett's esophagus. A barium follow-through study of the small bowel, performed in order to evaluate the continuity or stenotic change in the small bowel, revealed dilated and aggregated small bowel with normal peristalsis, suggesting abdominal cocoon (Figure 4). The ileus was resolved with conservative care over 3 days; the patient was advanced to a liquid diet; however, she complained of abdominal pain again. An abdominal computed tomography with gastrograffin was carried out; the small bowel was encapsulated from the distal jejunum to the mid ileum with adhesion of bowel loops and preservation of passage through the entire bowel (Figure 3).

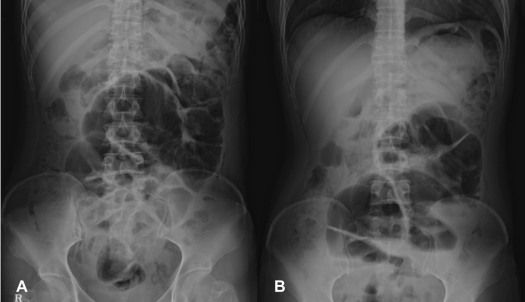

Figure 1.

Plain abdominal X-ray shows marked small bowel dilatation and air collection in the lumen with multiple air fluid levels in the upright position. The distended bowel loop was located centrally and extensively folded (A: supine position, B: upright position).

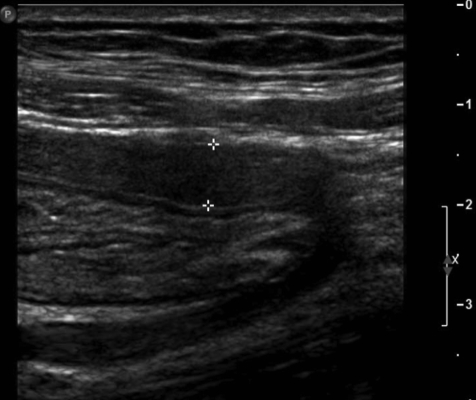

Figure 2.

Ultrasound of the abdomen shows small bowel surrounded by a continuous membranous structure. The thickness of the capsule was from 3.5 mm up to 6.1 mm.

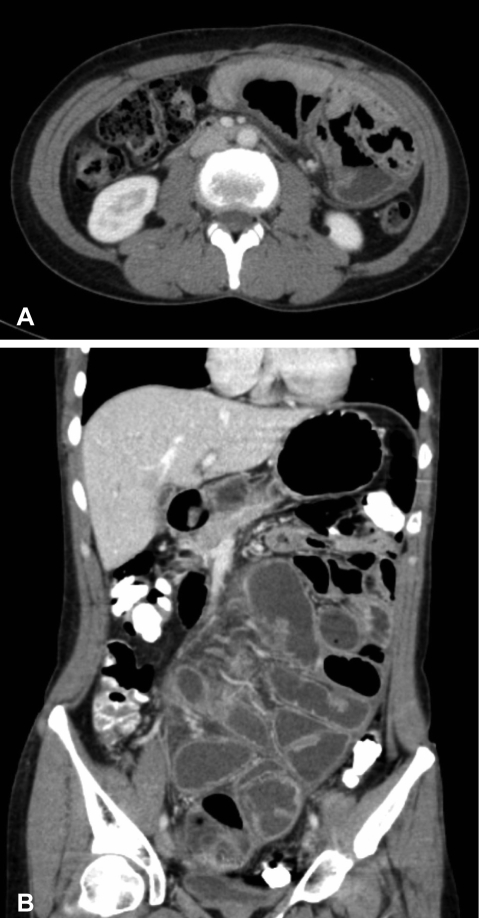

Figure 3.

(A) Contrast-enhanced abdomen-pelvis computed tomogram shows encapsulation of the entire small bowel with a sclerotic capsule. (B) Abdomen computed tomogram after intake of gastrograffin shows encapsulation of the small bowel from the distal jejunum to the mid ileum.

Figure 4.

Barium follow-through shows the entire dilated small bowel loop aggregated and deviated to left side of abdomen. There was no ulcerative change or obstructive material in the lumen of the bowel and normal peristalsis. A trace of barium in the ascending colon suggested little continuity from the small bowel to the colon.

Laparotomy exploration was finally performed for encapsulating peritonitis with intestinal partial obstruction. Exploration revealed encapsulation of the entire bowel with a whitish leather-like fibrous membrane and straw-colored ascitic fluid of a moderate amount (Figure 5). In addition, there was adhesion between the liver and gall bladder with a whitish fibrous band, but no nodular change on the surface of the liver. An adhesiolysis of the capsule encasing bowel revealed the serosa of the bowel loops attached to one another by a thin flimsy layer, which could be separated easily. The pathologic finding of the removed capsule was a dense collagenous fibrous tissue with mild chronic inflammation (Figure 6). After surgery, the patient was tolerated a gradually increased diet without any complication and was discharged, on hospital day 22.

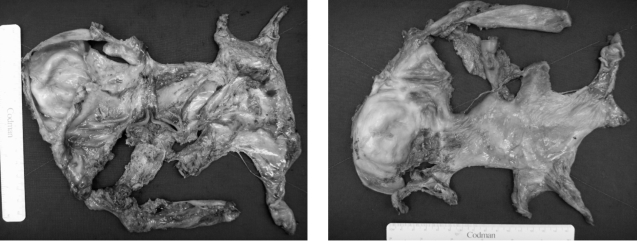

Figure 5.

Laparotomy exploration revealed encapsulation of the entire small bowel with a whitish leather like fibrous membrane. Adhesiolysis of the capsule encasing the bowel was performed.

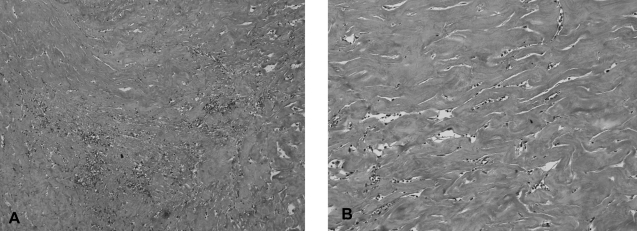

Figure 6.

The microscopic findings of the capsule shows dense collagenous fibrous tissue with mild chronic inflammation (A: ×100, B: ×200, H & E stain).

DISCUSSION

Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis is an uncommon but potentially lethal condition. It can lead to severe complications such as bowel obstruction, enterocutaneous fistulas and necrosis. Most cases are diagnosed incidentally at laparotomy. Preoperative diagnosis is confirmed readily by a combination of barium follow-through where a concertina pattern or cauliflower sign and delayed transit of contrast medium are characteristic and computed tomography of the abdomen where images show small bowel loops aggregated together at the center of the abdomen encased by a soft-tissue density mantle7, 8).

The management for SEP includes medical treatment and surgical intervention. Therapy with corticosteroids is effective in patients with secondary SEP. Tamoxifen, a nonsteroidal anti-estrogen drug, has been successfully used in the treatment of fibrosclerotic disorders9, 10). Surgery, such as membrane dissection and extensive adhesiolysis, is the treatment of choice for cases with intestinal obstruction. However, due to morbidity and mortality, resection of bowel is indicated only if the bowel is non-viable or is not completely separated from the capsule due to severe adhesion.

The pathogenesis of SEP remains uncertain. However, recurrent peritonitis has been reported as the main cause of secondary SEP5, 6). Other factors that may lead to SEP include the following. Sterilizing chemicals, buffers, hypertonic dextrose, chronic use of β-blocking agent, acidic dialysate, peritoneal catheter itself, drugs added to dialysis fluid, and endotoxin contamination of in line microbiologic filters11, 12). Rarely, SEP is also associated with abdominal tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, familial Mediterranean fever, gastrointestinal malignancy, protein-S deficiency, liver transplantation, fibrogenic foreign material, and luteinized ovarian thecomas13).

This report describes a case of abdominal cocoon in a Korean woman with intermittent partial obstruction of small bowel. Accurate pre-operative diagnosis makes it possible for the surgeon to perform extensive adhesiolysis and removal of the capsule encasing small bowel without resection of the bowel. The patient had no history of chronic continuous peritoneal dialysis but had a history of chronic abdominal pain after hysterectomy. There has been no report on the association of SEP with hysterectomy or gestational trophoblastic disease to date. There are a few reports of abdominal cocoon in patients with liver transplantation or treatment for liver cirrhosis who did not have a history of peritoneal-venous shunting (PVS) or β-blocker medication. These findings suggest that sclerosing peritonitis may be due to persistent low-grade intra-abdominal sepsis14, 15). Nakamura et al. reported that SEP pathogenesis in long-term CAPD patients might be related to advanced glycation end-product accumulation in the peritoneal membrane and alteration in peritoneal cell function, accompanied by increased expression of various growth factors and peritoneal sclerosis, and finally followed by SEP. Therefore, long-term peritoneal stimulation with certain products associated with peritonitis, of various causes, could cause SEP16). In our case, SEP may have been associated with chronic and recurrent peritonitis after abdominal open surgery.

The causes of SEP may be much more diverse than previously thought. Study of additional SEP cases is needed to facilitate precise and rapid diagnosis and treatment as well as considerations for prevention.

References

- 1.Lee HY, Kim BS, Choi HY, Park HC, Kang SW, Choi KH, Ha SK, Han DS. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis as a complication of long term continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Korea. Nephrology. 2003;8(Suppl):S33–S39. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1797.8.s.11.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawaguchi Y, Kawaguchi H, Mujais S, Topley N, Oreopoulos DG. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: definition, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Perit Dial Int. 2000;20(Suppl 4):S43–S55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foo KT, Ng KC, Rauff A, Foong WC, Sinniah R. Unusual small intestinal obstruction in adolescent girls: the abdominal cocoon. Br J Surg. 1978;65:427–430. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800650617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marinho A, Adelusi B. The abdominal cocoon: a case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87:249–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1980.tb04529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollock CA. Bloody ascites in a patient after transfer from peritoneal dialysis to hemodialysis. Semin Dial. 2003;16:406–410. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2003.16088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ing TS, Daugirdas JT, Gandhi VC. Peritoneal sclerosis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 1984;4:173–176. doi: 10.1159/000166799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serafimidis C, Katsarolis I, Vernadakis S, Rallis G, Giannopoulos G, Legakis N, Peros G. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (or abdominal cocoon) BMC Surg. 2006;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hur J, Kim KW, Park MS, Yu JS. Abdominal cocoon: preoperative diagnostic clues from radiologic imaging with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:639–641. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Celicout B, Levard H, Hay J, Msika S, Fingerhut A, Pellissier E. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: early and late results of surgical management in 32 cases. Dig Surg. 1998;15:697–702. doi: 10.1159/000018681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarasam I, Mathew G, Siaram V, Perakath B, Rao A, Nair A. The abdominal cocoon and an effective technique of surgical management. Trop Gastroenterol. 2005;26:51–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown P, Baddeley H, Read AE, Davies J. Scerosing peritonitis, an unusual reaction to a adrenergic-blocking drug (Practolol) Lancet. 1974;2:1477–1481. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rottembourg J, Issad B, Langlois P, Tranbalc R, Amadou A, Degroc E, Legrain M. Loss of ultrafiltration and sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis during CAPD. Evaluation of the potential risk factors. Adv Perit Dial. 1985;1:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins SB, Lang BL, Shortland JR, Brown PW, Wilkie ME. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case series from a single U.K. center during a 10 year period. Adv Perit Dial. 2001;17:191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maguire D, Srinivasan P, O'Grady J, Rela M, Heaton ND. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis after orthotopic liver transplantion. Am J Surg. 2001;182:151–154. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto S, Sato Y, Takeishi T, Kobayashi T, Hatakeyama K. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in two patients with liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:172–175. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura S, Niwa T. Advanced glycation end-products and peritoneal sclerosis. Semin Nephrol. 2004;24:502–505. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]